Almost 50 years ago, Francis Crick and James Watson observed that “almost all small viruses are either spheres or rods” and put forth the hypothesis that such viruses were symmetrical arrays of subunits (1). In the following paper in that issue of Nature, Donald Caspar demonstrated that tomato bushy stunt virus had at least cubic symmetry and provided the first evidence for icosahedral symmetry in a biological molecule (2). About half of all virus families share icosahedral geometry, even though they may have nothing else in common. In this issue of PNAS, Zandi et al. (3) have investigated the physical basis for the prevalence of icosahedral symmetry by using a simplest case model: circular elements tiling the surface of a more or less spherical solid. The resulting model can produce the complex behavior observed in solution experiments. Their results strongly support a corollary implicit in Crick's hypothesis: the physical properties of icosahedra lead to their prevalence in biology. Here, I will briefly discuss the paper by Zandi et al. and compare it to some recent theoretical and biochemical studies of virus structure and assembly.

Icosahedral Symmetry

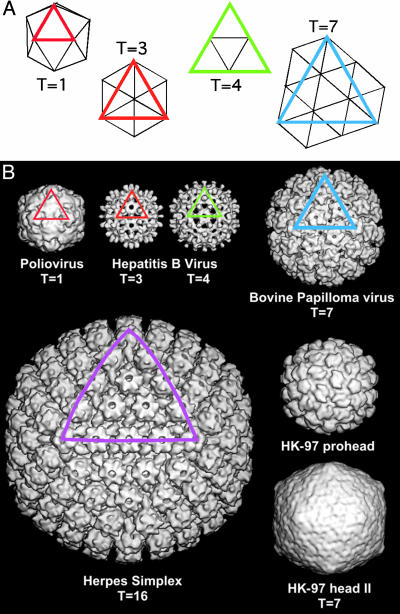

To understand the nature and application of Zandi et al.'s argument, it is probably best to start with a description of icosahedral symmetry. An icosahedron is 20-sided solid, where each facet has threefold symmetry (Fig. 1A). To build an icosahedron out of protein, each face must be made of at least three proteins, because an individual protein cannot have intrinsic threefold symmetry. In an icosahedron, the proteins are related by exact two-, three-, and fivefold symmetry axes. It turns out that few spherical viruses are built of 60 subunits (3 × 20), but most viruses are built of T multiples of 60, where the T (for triangulation) number indicates the number of subunits within each of the 60 icosahedral asymmetric units (4). The term quasi-equivalence indicates that the subunits are in distinct but quasi-equivalent environments. In this manner, some subunits are arranged around icosahedral fivefold axes and others are arranged as hexamers. Quasi-equivalence is readily apparent in a virus structure by the presence of pentameric and hexameric groupings of subunits, the capsomers (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Different arrangements of icosahedral symmetry. (A)A T = 1 icosahedron has 20 triangular facets, each of which has threefold symmetry; an icosahedron has 20 × 3 = 60 equivalent asymmetric units. Larger facets can be cut out of hexagonal lattice, resulting in facets where smaller triangles are arranged around local quasi-sixfolds. The area of the larger facet is T = h2 + hk + k2, where h and k are integers (h ≥ 1 and k ≥ 0). A T = 3 facet has three smaller triangles and nine subunits, but it still has only three asymmetric units. (B) A selection of cryoelectron microscopy image reconstructions demonstrating different T numbers: polio (T = 1), small hepatitis B virus (HBV) capsid (T = 3), large HBV capsid (T = 4), bacteriophage HK97 (T = 7), and herpes simplex virus (T = 16). Bovine papilloma virus, like all papovaviruses, has a T = 7 lattice, but is assembled exclusively from pentamers. An icosahedral facet is highlighted on selected images. [Image in A reproduced with permission from ref. 16 (Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science, Amsterdam).] The reconstructions in B are courtesy of Alasdair Steven and coworkers (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda).

Fundamental Models and Complex Behavior

Zandi et al. identified the most stable arrangements of circular capsomers on different sized spheres by Monte Carlo methods. Capsomers interacted via a van der Waals-like force field. This approach built on an earlier analysis of the stability of “tiled” spheres, which showed that nonicosahedral arrangements of capsomers could yield reasonably stable capsids (5). When capsomers were allowed to “equilibrate” between pentamer and hexamer forms, the most stable species were the series of quasi-equivalent icosahedra. This is not to say that nonicosahedral forms were unstable, but at equilibrium they would be vanishingly rare. The nonicosahedral structures are intriguing: they may be a window into the structure of retrovirus provirions, which are heterogeneous in size, nonicosahedral, possess local sixfold symmetry, yet according to Euler's theorem still contain 12 fivefolds (6–9). Thus, retroviral capsids may represent a kinetic trap unable to successfully reorganize into an icosahedral isomer.

Another demonstration of the power of this fundamental model based on primitive capsomers is its response to perturbation. When the model capsids are swollen, capsids may burst along shear lines, reminiscent of maturation mutants of Flock House Virus (10). Pentamers absorbed strain when a capsid was deformed, suggestive of the behavior of fivefolds in bacteriophages HK97 and P22 as the respective capsids are stressed (11, 12).

The paper by Zandi et al. (3) is part of a recent burst of activity by physicists and mathematicians in the field of virology. A good example of this is the recent satellite workshop on “Mathematical Virology,” supported by the Isaac Newton Institute and the London Mathematical Society, organized by Reidun Twarock. Participants at that workshop ranged from condensed matter physicists to structural virologists; some of the published work from participants is relevant to this discussion.

Nelson and coworkers (13) considered how a growing sheet, analogous to an icosahedral facet, with an intrinsic curvature would be limited (by accumulated strain and statistical factors) to a distribution of sizes. Such a distribution can be observed in retroviruses and other pleiomorphic viruses. Most icosahedral viruses are very uniform. In some viruses, the size distribution may be limited by the intrinsic curvature of subunits and scaffold proteins. The recently discovered tape-measure function of a protein in a large bacteriophage (D. Stuart and D. Bamford, personal communication) is a biological mechanism for maintaining homogeneity that perfectly responds to the mechanism for heterogeneity based on theory (13).

Assembly models can be developed that are specific for biologically observed geometry.

Where Zandi et al. considered spherical capsomers that conformed to quasi-equivalence, Twarock (14) examined alternative tiling strategies. Twarock's alternatives are icosahedral but provide a clever way of viewing deviations from the ideality of quasi-equivalent predictions, such as those presented by papovaviruses where pentamers occupy hexavalent lattice points (Fig. 1B). By using a more detailed geometric description, assembly models can be developed that are specific for biologically ob served geometry.

Simple geometric figures are a far cry from a detailed virus structure, but are perfect for build-up experiments and course-grained simulations of assembly. Build-up “games” allow identification of intermediates along an assembly path and provide a means for developing master (thermodynamic–kinetic) equation descriptions of capsid assembly (15, 16). Thermodynamic–kinetic models have been very successful in explaining the behavior of in vitro assembly reactions (16, 17), but they say little about the details of the assembly of single particles. However, course-grained molecular dynamics can provide a detailed picture of successful assembly of simple particles (18) or test proposed mechanisms for regulating assembly and quasi-equivalence (19, 20).

What Is the Value of Understanding Virus Stability and Assembly?

Virus life cycle is regulated at many levels. A great deal of effort has been invested in studying regulation at the level of viral nucleic acid replication, interference with cell cycle, synthesis of viral proteins, and so on. A virus capsid must assemble at the right time and place to (be ready to) package the right nucleic acid, it must be able to undergo conformational transitions if required, and it must be able release its nucleic acid. The capsid must be tough and fragile, the subunits refractory to assembly and readily assembled. Part of the key to these paradoxes is the role of hysteresis in stability (16, 21) and the recent observation that hepatitis B virus assembly may be subject to allosteric regulation (22). Studies of assembly models have also led to the hypothesis that assembly can be misdirected (16, 19, 23). The recent discovery of a highly effective misdirector for hepatitis B virus (24) is a case of biological experiment replicating fundamental predictions.

The interplay between theoretical and solution studies is powerful and valuable. Physicists studying soft condensed matter provide a framework that will help interpret and rationalize virological experimental observations. Conversely, virologists provide experimental observations that are constraints and test the application of theory. Different scientific approaches reveal new questions and answers that expand our understanding of viruses and the means to combat them.

See companion article on page 15556.

References

- 1.Crick, F. H. C. & Watson, J. D. (1956) Nature 177, 473-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caspar, D. L. D. (1956) Nature 177, 476-477. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zandi, R., Reguera, D., Bruinsma, R. F., Gelbart, W. M. & Rudnick, J. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 15556-15560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caspar, D. L. D. & Klug, A. (1962) Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 27, 1-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruinsma, R. F., Gelbart, W. M., Reguera, D., Rudnick, J. & Zandi, R. (2003) Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 248101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuller, S. D., Wilk, T., Gowen, B. E., Krausslich, H. G. & Vogt, V. M. (1997) Curr. Biol. 7, 729-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganser, B. K., Li, S., Klishko, V. Y., Finch, J. T. & Sundquist, W. I. (1999) Science 283, 80-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nermut, M. V., Hockley, D. J., Bron, P., Thomas, D., Zhang, W. H. & Jones, I. M. (1998) J. Struct. Biol. 123, 143-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeager, M., Wilson-Kubalek, E. M., Weiner, S. G., Brown, P. O. & Rein, A. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 7299-7304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneemann, A., Dasgupta, R., Johnson, J. E. & Rueckert, R. R. (1993) J. Virol. 67, 2756-2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conway, J. F., Wikoff, W. R., Cheng, N., Duda, R. L., Hendrix, R. W., Johnson, J. E. & Steven, A. C. (2001) Science 292, 744-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teschke, C. M., McGough, A. & Thuman-Commike, P. A. (2003) Biophys. J. 84, 2585-2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lidmar, J., Mirny, L. & Nelson, D. R. (2003) Phys. Rev. E 68, 051910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Twarock, R. (2004) J. Theor. Biol. 226, 477-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wales, D. J. (1987) Chem. Phys. Lett. 141, 478-484. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zlotnick, A. & Stray, S. J. (2003) Trends Biotechnol. 21, 536-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casini, G. L., Graham, D., Heine, D., Garcea, R. L. & Wu, D. T. (2004) Virology 325, 320-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rapaport, D. C., Johnson, J. E. & Skolnick, J. (1999) Comp. Phys. Commun. 121, 231-235. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger, B., Shor, P. W., Tucker-Kellogg, L. & King, J. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 7732-7736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz, R., Shor, P. W., Prevelige, P. E. J. & Berger, B. (1998) Biophys. J. 75, 2626-2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber, G., Da Poian, A. T. & Silva, J. L. (1996) Biophys. J. 70, 167-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stray, S. J., Ceres, P. & Zlotnick, A. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 9989-9998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prevelige, P. E. J. (1998) Trends Biotechnol. 16, 61-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hacker, H. J., Deres, K., Mildenberger, M. & Schroder, C. H. (2003) Biochem. Pharmacol. 66, 2273-2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]