Abstract

Aims

To investigate, in a 26‐week, open‐label, randomized, treat‐to‐target trial, the efficacy and safety of insulin degludec/insulin aspart (IDegAsp) once daily vs insulin glargine (IGlar) once daily in adults with Type 2 diabetes, inadequately controlled on basal insulin.

Methods

Participants were randomized (1:1) to IDegAsp once daily or IGlar once daily in combination with existing oral antidiabetic drugs. IDegAsp once daily was administered with the main evening meal or the largest meal of the day (agreed at baseline); dosing time was maintained throughout the trial. Participants titrated their insulin dose weekly to a mean pre‐breakfast self‐measured plasma glucose target [3.9–4.9 mmol/l (70–89 mg/dl)].

Results

IDegAsp once daily was non‐inferior to IGlar once daily in reducing HbA1c after 26 weeks [mean estimated treatment difference IDegAsp once daily − IGlar once daily: −0.03% (95% CI −0.20, 0.14)]. The evening meal glucose increment was significantly lower with IDegAsp once daily vs IGlar once daily [estimated treatment difference IDegAsp once daily − IGlar once daily: −1.32 mmol/l (95% CI −1.93, −0.72); P < 0.05]. The overall confirmed hypoglycaemia rate was higher with IDegAsp once daily (estimated rate ratio 1.43; 95% CI 1.07, 1.92; P < 0.05). The rate of nocturnal hypoglycaemia did not significantly differ between the IDegAsp and IGlar groups [estimated rate ratio 0.80 (95% CI 0.49, 1.30); not significant].

Conclusions

In participants with Type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on basal insulin, IDegAsp once daily improved glycaemic control and was non‐inferior to IGlar once daily. IDegAsp led to higher rates of overall hypoglycaemia than IGlar, with no significant difference in rates of nocturnal hypoglycaemia.

What's new?

After 26 weeks, treatment with insulin degludec/insulin aspart (IDegAsp) once daily effectively improved glycaemic control and was non‐inferior to insulin glargine (IGlar) once daily in terms of lowering HbA1c in participants with Type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on basal insulin.

Compared with IGlar, higher rates of overall hypoglycaemia were observed with IDegAsp, primarily in relation to the meal at which it was dosed (IDegAsp was administered once daily at the same fixed meal every day). The possibility of using IDegAsp once daily offers flexibility in the injection and provides both specific mealtime coverage and the benefits of full 24‐h basal coverage in a single injection.

What's new?

After 26 weeks, treatment with insulin degludec/insulin aspart (IDegAsp) once daily effectively improved glycaemic control and was non‐inferior to insulin glargine (IGlar) once daily in terms of lowering HbA1c in participants with Type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on basal insulin.

Compared with IGlar, higher rates of overall hypoglycaemia were observed with IDegAsp, primarily in relation to the meal at which it was dosed (IDegAsp was administered once daily at the same fixed meal every day). The possibility of using IDegAsp once daily offers flexibility in the injection and provides both specific mealtime coverage and the benefits of full 24‐h basal coverage in a single injection.

Introduction

As β‐cell function progressively declines in people with Type 2 diabetes 1, intensification of insulin therapy with prandial insulin is often required to maintain glycaemic control and avoid the long‐term consequences of uncontrolled hyperglycaemia 2, 3, 4. Currently intensification is achieved by adding one or more prandial insulin injections to a basal insulin regimen (basal–bolus), or by switching to a premixed biphasic insulin; for example, biphasic insulin aspart or insulin lispro mix 1.

Basal–bolus insulin regimens offer mealtime and between‐meal insulin coverage, but people may perceive these regimens to be intrusive and burdensome 5, 6. Injections of premixed, biphasic insulin regimens offer a less stringent alternative to provide prandial coverage for multiple meals 1; however, these may be associated with an increased rate of overall 7 and nocturnal hypoglycaemia 8 because interaction between the soluble and protaminated components results in a prolonged and uneven peak glucose‐lowering effect compared with rapid‐acting insulins and a duration of action of <24 h 9. Until recently, combining a long‐acting basal insulin with a distinct rapid‐acting insulin in a single injection was not feasible as the properties of the individual components are adversely affected by co‐formulation 10.

Insulin degludec/insulin aspart (IDegAsp) is a soluble combination of an ultra‐long‐acting basal insulin degludec (IDeg; 70%), and the rapid‐acting insulin analogue, insulin aspart (IAsp; 30%). The two components IDeg and IAsp coexist separately in solution 11, allowing them to be co‐formulated within a single injection. Upon subcutaneous injection, IDeg immediately forms stable multihexamers, resulting in a soluble tissue depot from which IDeg monomers slowly dissociate, while IAsp monomers are rapidly released into the circulation 11. Pharmacodynamic studies have shown that the IDeg and IAsp components remain distinct in IDegAsp and provide separate prandial and basal glucose‐lowering effects, with a peak action attributable to IAsp and a flat, stable basal effect attributable to IDeg, sustainable for >24 h 12. The latter is in contrast to existing premixed insulins, which contain a rapid‐acting insulin analogue with a protaminated analogue that has an intermediate action profile 13, 14. A limitation of premixed insulin and of fixed‐dose combination products, therefore, is the fixed ratio of prandial to basal insulin dose and that the doses can be complex to titrate 1.

The clinical benefits of IDegAsp were demonstrated in a phase III trial of people with Type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on pre‐ or self‐mixed insulin 15. Twice‐daily IDegAsp effectively improved HbA1c and provided superior fasting plasma glucose (FPG) control and significantly lower rates of both overall confirmed and nocturnal confirmed hypoglycaemia vs biphasic insulin aspart 30 15. Lower FPG with IDegAsp twice daily vs biphasic insulin aspart 30 twice daily was also reported in a pan‐Asian trial of participants with Type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on basal, pre‐ or self‐mixed insulin + oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs) 16.

Although clinical trials have shown the potential clinical benefits of IDegAsp twice daily vs premix insulins 15, 16, some people may prefer to use IDegAsp once daily as a straightforward way to intensify treatment 12. The present trial investigated the efficacy and safety of IDegAsp once daily vs insulin glargine (IGlar) once daily, in insulin‐experienced participants with Type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on basal insulin + OADs for ≥ 3 months.

Patients and methods

Trial population

Adults aged ≥ 18 years with a confirmed diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes ≥ 6 months before enrolment, HbA1c 53–86 mmol/mol (7.0–10.0%), BMI ≤ 40 kg/m2, and previously treated with a once‐daily basal insulin regimen (detemir, glargine or neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin) + metformin (+/− other OADs) for at least 3 months before randomization were included. Participants were excluded if they: were on diabetes treatment regimens other than those specified above in the 3 months before the trial; had a total daily insulin dose of > 1 U/kg; had cardiovascular disease diagnosed within 6 months of the trial (defined as stroke, decompensated heart failure New York Heart Association class III or IV, myocardial infarction, unstable angina pectoris or coronary arterial bypass graft or angioplasty); had uncontrolled, severe hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 180 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 100 mmHg); or had impaired renal or hepatic function. Participants who anticipated significant lifestyle changes during the study (e.g. permanent night/evening shift workers, highly variable eating habits) were excluded.

Trial design and procedures

The trial was an international multicentre 26‐week, randomized, open‐label, parallel‐group, treat‐to‐target trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01045447; EudraCT: 2008‐005767‐34), comparing the efficacy and safety of IDegAsp once daily with IGlar once daily, both in combination with metformin ± pioglitazone ± a dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitor in participants with Type 2 diabetes from Croatia, France, India, Poland, South Africa, South Korea, Sweden, Turkey and the USA.

The trial was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the protocol was approved by the appropriate local institutional review boards and ethics committees. All participants provided informed written consent.

Participants were randomized (1:1) to IDegAsp once daily or IGlar once daily and stratified according to prior pioglitazone use (for equal group representation). Participants continued with metformin ± pioglitazone ± dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors; other OADs were discontinued at the start of the trial. IDegAsp was administered once daily with the main evening meal or with the largest meal at a dosing time as agreed by the participant and the investigator (at treatment initiation) and the participants continued administering IDegAsp with the same meal throughout the trial. IGlar was administered according to the approved labelling (once‐daily dosing at the same time of day).

Participants were switched on a 1:1 unit basis from their current insulin to trial insulin, thus continuing with the same total daily insulin dose they received before inclusion. Participants’ insulin doses were titrated weekly to a pre‐breakfast plasma glucose target of 3.9–4.9 mmol/l (70–89 mg/dl), based on mean pre‐breakfast plasma glucose from the preceding 3 days using a predefined titration algorithm (Table S1).

Study endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint was change from baseline in HbA1c (mmol/mol [%]) after 26 weeks. Secondary efficacy endpoints included change from baseline in FPG, changes in nine‐point self‐measured plasma glucose (SMPG) and the overall prandial glucose increment (derived from the nine‐point SMPG profile as the difference between plasma glucose levels pre‐ and post‐meal). The proportion of participants achieving HbA1c < 53 mmol/mol (< 7.0%) at week 26 with/without confirmed hypoglycaemia during the last 12 weeks of the trial was also calculated.

Safety assessments included number, type and severity of adverse events (AEs), insulin dose, body weight, standard laboratory tests and hypoglycaemic events. Confirmed hypoglycaemic episodes included either episodes confirmed by plasma glucose level < 3.1 mmol/l (< 55.9 mg/dl) or severe episodes requiring assistance from another person to treat (as defined by the American Diabetes Association guidelines) with no plasma glucose level confirmation needed. Hypoglycaemia was classified as ‘nocturnal’ if the time of onset was at 00.01–5.59 h (inclusive).

Statistical analysis

The primary objective of the study was to confirm non‐inferiority of IDegAsp once daily vs IGlar once daily as assessed by the change from baseline to week 26 in HbA1c, using a prespecified non‐inferiority limit of 0.4% for the between‐treatment difference. The primary endpoint was analysed using anova, with treatment, antidiabetic therapy at screening, sex and region as fixed factors, and age and baseline HbA1c as covariates. Change from baseline in FPG, body weight, nine‐point SMPG and prandial glucose increment were analysed using an anova similar to that used for the primary endpoint. The responder analysis [proportion of participants with HbA1c < 53 mmol/mol (< 7.0%) with/without hypoglycaemia] was conducted separately using a logistic regression model with treatment, OAD therapy at screening, sex and region as fixed factors, and age and baseline HbA1c as covariates.

The number of hypoglycaemic episodes was analysed using a negative binomial regression model with a log‐link function and the logarithm of the time period in which a hypoglycaemic episode occurred was considered treatment‐emergent as offset. Treatment, antidiabetic therapy at screening, sex and region were included as fixed factors and age as covariate. Incidence of treatment‐emergent AEs and serious AEs (SAEs) were summarized using descriptive statistics.

Results

Participant characteristics

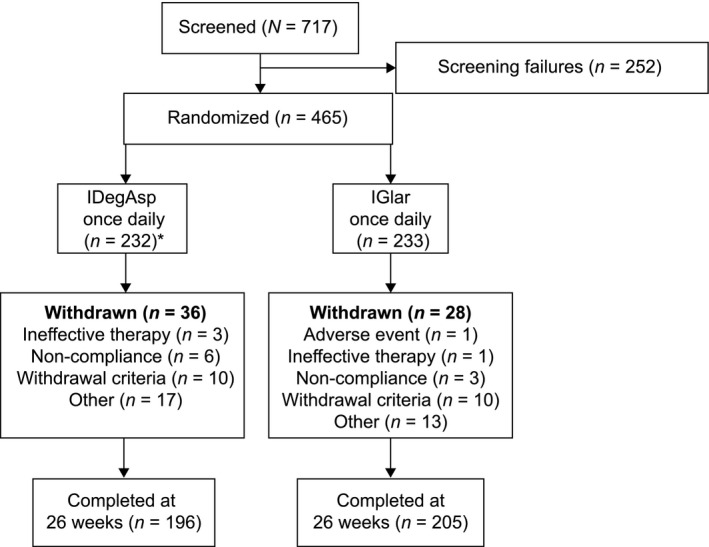

Of 717 participants screened, 465 were randomized to IDegAsp once daily or IGlar once daily; 401 participants completed the study (196 on IDegAsp, 205 on IGlar; Fig. 1). At screening, of 267 subjects previously treated with IGlar, 143 subjects were randomized to the IGlar treatment group (57.7%). Baseline characteristics including the level of glycaemic control, duration of diabetes, BMI and previous treatment regimen were generally similar between both groups (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Trial flow diagram. *Two participants randomized to insulin degludec/insulin aspart (IDegAsp) were withdrawn from the trial before receiving insulin treatment as they were screening failures for whom a randomization call was placed in error. Withdrawal criteria included pregnancy, hypoglycaemia during the trial that was deemed a safety problem, major protocol deviations or initiation or significant change to medication that could interfere with glucose metabolism. Other criteria included instances where participants donated blood or a lack of efficacy of trial drug after 12 weeks. In total, 20 subjects were withdrawn because they met one of the withdrawal criteria [IDegAsp 10 subjects and insulin glargine (IGlar) 10 subjects]. Of these 20 subjects, 18 were withdrawn because of protocol deviations (IDegAsp, n = 9; IGlar, n = 9), one subject was withdrawn because of the occurrence of hypoglycaemia (IDegAsp group) and one was withdrawn as a result of the initiation of or significant change in a systemic treatment that, in the investigator's opinion, could have interfered with glucose metabolism (IGlar group.)

Table 1.

Characteristics of trial population exposed to treatment

| Characteristic | IDegAsp once daily (n = 230) | IGlar once daily (n = 233) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex: men/women, % | 58.7/41.3 | 54.5/45.5 |

| Age, years | 57.8 (9.5) | 58.4 (10.1) |

| Weight, kg | 84.7 (19.9) | 83.9 (19.2) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.1 (5.1) | 30.1 (5.3) |

| Country of residence, n (%) | ||

| Croatia | 11 (4.8) | 11 (4.7) |

| France | 11 (4.8) | 10 (4.3) |

| India | 61 (26.5) | 47 (20.2) |

| Poland | 21 (9.1) | 11 (4.7) |

| South Africa | 10 (4.3) | 14 (6.0) |

| South Korea | 19 (8.3) | 23 (9.9) |

| Sweden | 18 (7.8) | 20 (8.6) |

| Turkey | 17 (7.4) | 16 (6.9) |

| USA | 62 (27.0) | 81 (34.8) |

| Duration of diabetes, years | 11.6 (6.8) | 11.4 (7.3) |

| HbA1c *, mmol/mol | 67.2 | 68.3 |

| HbA1c, % | 8.3 (0.8) | 8.4 (1.0) |

| FPG, mmol/l | 8.0 (2.5)‡ | 7.8 (2.8)† |

| FPG*, mg/dl | 144 (45) | 140 (50) |

| Prestudy treatment regimen, n (%) | ||

| Basal insulin + metformin | 94 (40.9) | 96 (41.2) |

| Basal insulin + metformin + other OADs† | 109 (47.4) | 108 (46.4) |

| Basal insulin + metformin + pioglitazone | 27 (11.7) | 29 (12.4) |

FPG, fasting plasma glucose; IDegAsp, insulin degludec/insulin aspart; IGlar, insulin glargine; OAD, oral antidiabetic drug.

All data are means (sd), unless otherwise specified.

*Calculated, not measured.

†40.2% of participants were on one OAD at screening; 45.1% of participants used two OADs (biguanide was used by all these participants and the second OAD was most commonly sulphonylurea or glinide). Thiazolidinedione was used by ~12.1% of participants overall. All OADs other than metformin, pioglitazone and dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors were discontinued at the start of the trial period.

‡ n = 228;† n = 231.

Dose timing

At week 1, IDegAsp and IGlar were most commonly injected with the main evening meal (60.2 and 43.3%, respectively) with smaller proportions of participants injecting at lunchtime (18.6 and 6.5%, respectively) and breakfast (11.5 and 14.3%, respectively); for the remaining participants, the injection time was with another meal or not known (9.7 and 35.9%, respectively). A similar pattern of injection times was observed at the end of the trial (week 26); the most common injection time for participants on IDegAsp or IGlar was with the main evening meal (65.0 and 39.4%, respectively) compared with 18.5 and 8.7%, respectively, at lunchtime, and 8.5 and 14.9% at breakfast, respectively. For the remaining participants, the injection time was with another meal or not known (8.0 and 37.0% for participants on IDegAsp and IGlar, respectively).

Glycaemic control

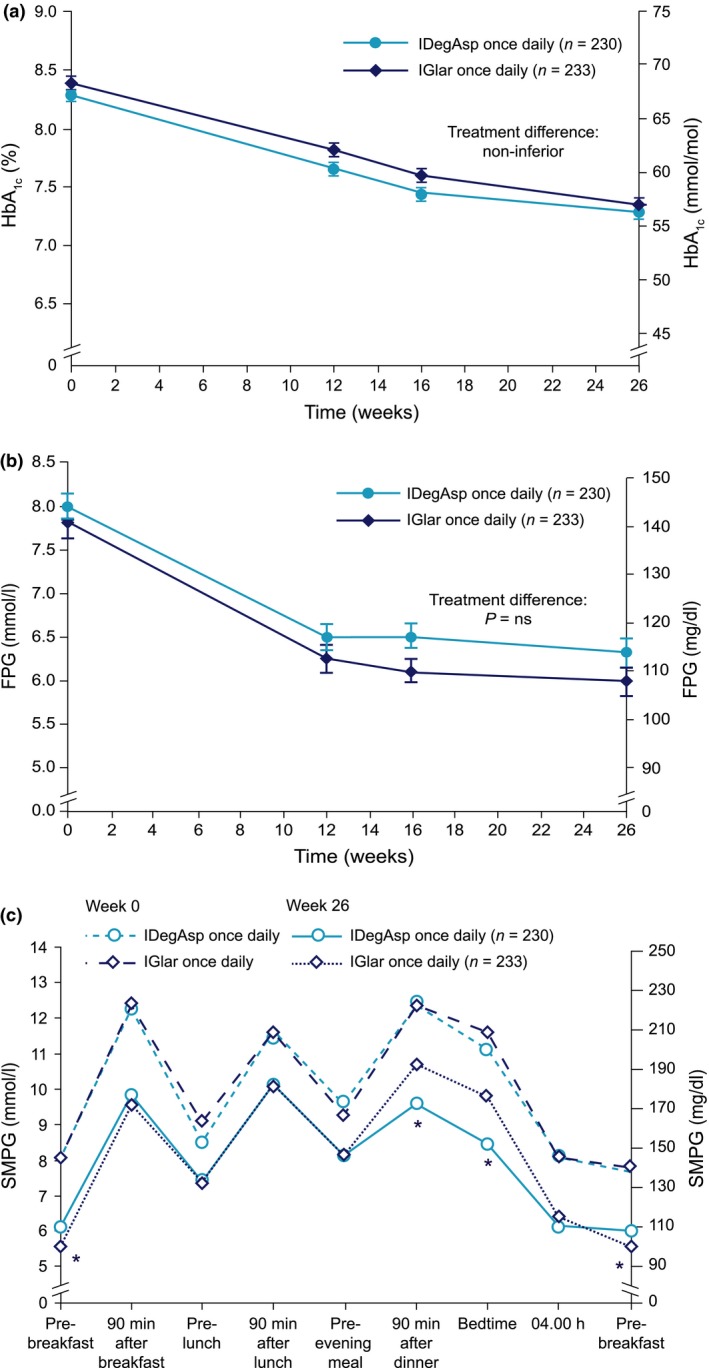

Similar mean HbA1c reductions were observed in both groups over the course of 26 weeks. The mean HbA1c at the end of the treatment period was 56 mmol/mol (7.3%) and 57 mmol/mol (7.4%), for IDegAsp and IGlar, respectively, representing mean HbA1c changes from baseline of −13 mmol/mol in both groups. The corresponding percentage change from baseline was −1.00% and −0.97% for IGlar and IDegAsp, respectively (Fig. 2a). The mean estimated treatment difference (ETD; IDegAsp once daily − IGlar once daily) after 26 weeks was −0.03% (95% CI −0.20, 0.14; not significant) confirming that IDegAsp was non‐inferior to IGlar, as the upper limit of the CI was well below the predefined non‐inferiority boundary of 0.4%.

Figure 2.

(a) Mean HbA1c over time for insulin degludec/insulin aspart (IDegAsp) once daily and insulin glargine (IGlar) once daily. (b) Mean fasting plasma glucose (FPG) over time for insulin IDegAsp once daily and IGlar once daily. (c) Mean self‐measured plasma glucose (SMPG) profile at baseline and at week 26 for IDegAsp once daily and IGlar once daily. ns, not significant. *Statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

The proportions of participants achieving HbA1c < 53 mmol/mol (< 7.0%) were 40.0 and 36.5% for IDegAsp once daily and IGlar once daily, respectively (odds ratio 1.18, 95% CI 0.78, 1.78; not significant). The proportion of participants who achieved HbA1c < 53 mmol/mol (< 7.0%) without confirmed hypoglycaemia in the last 12 weeks of the trial was 20.9% in the IDegAsp group and 23.5% in the IGlar group, respectively (odds ratio 0.80, 95% CI 0.50, 1.30; not significant).

Levels of FPG decreased from 8.0 mmol/l (144.0 mg/dl) at baseline to 6.3 mmol/l (113.4 mg/dl) with IDegAsp and from 7.8 mmol/l (140.4 mg/dl) to 6.0 mmol/l (108.0 mg/dl) with IGlar [ETD 0.33 mmol/l; 95% CI −0.11, 0.77 (ETD 5.9 mg/dl; 95% CI −2.0, 13.9; not significant)] at week 26 (Fig. 2b).

The mean nine‐point SMPG profiles at baseline were similar in the two groups and generally decreased during treatment (Fig. 2c). At week 26, mean SMPG measurements after the main evening meal [mean ETD (IDegAsp once daily − IGlar once daily) −1.21 mmol/l; 95% CI −1.85, −0.57 (ETD 21.8 mg/dl; 95% CI −33.3, −10.3)] and before bedtime (ETD (IDegAsp once daily − IGlar once daily) −1.29 mmol/l; 95% CI −1.92, −0.66 (ETD 23.2 mg/dl; 95% CI −34.6, −11.9)] were significantly lower with IDegAsp than with IGlar [P < 0.05 (Fig. 2c)]. Similarly, at week 26, mean SMPG measurements before breakfast were significantly lower [ETD (IDegAsp once daily − IGlar once daily) 0.55 mmol/l; 95% CI 0.23, 0.88 (ETD 9.9 mg/dl; 95% CI 4.1, 15.9)] with IGlar than with IDegAsp (P < 0.05).

After 26 weeks, the mean prandial glucose increments, overall and at main evening meal, were significantly lower with IDegAsp once daily than with IGlar once daily: ETD (IDegAsp once daily − IGlar once daily) −0.65 mmol/l; 95% CI −1.00; −0.30 (ETD −11.7 mg/dl; 95% CI −18.0, −5.4), and ETD (IDegAsp once daily − IGlar once daily) −1.32 mmol/l; 95% CI −1.93, −0.72 (ETD −23.8 mg/dl; 95% CI −34.8, −13.0); P < 0.001, respectively. No statistically significant differences were identified in the mean prandial increments after breakfast and lunch.

Insulin dose

The mean total daily insulin dose was 60 U (0.69 U/kg) for both groups at week 26.

Body weight

The estimated mean change in body weight from baseline was similar in both groups. The weight gain was 1.74 kg with IDegAsp vs 1.41 kg with IGlar [ETD (IDegAsp once daily − IGlar once daily) 0.33 kg; 95% CI −0.17, 0.83; not significant].

Hypoglycaemic events

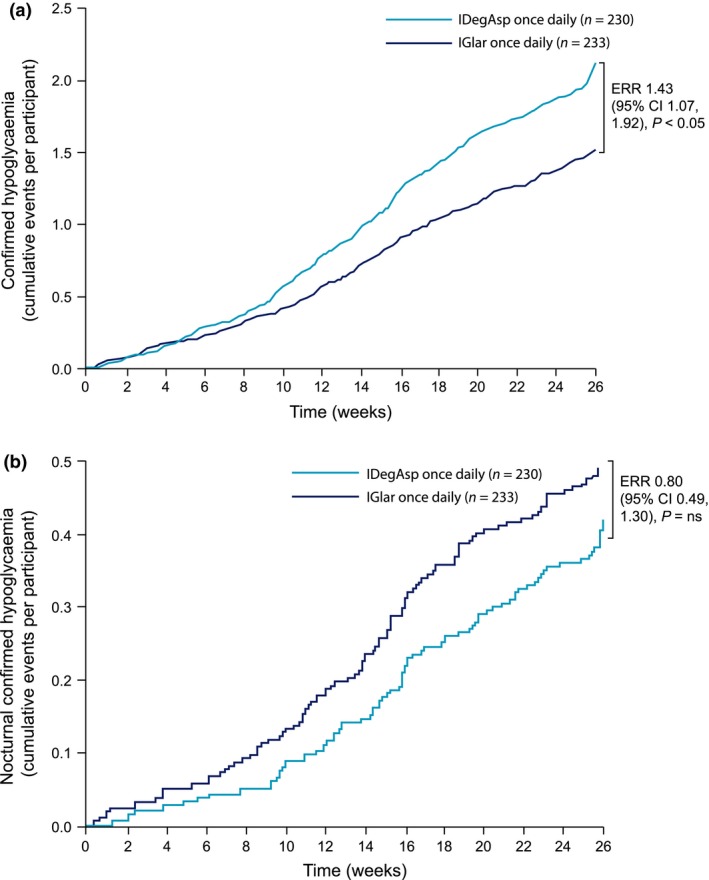

Confirmed hypoglycaemia was reported in 52.6% (n = 121) of participants on IDegAsp and 48.1% (n = 112) of participants on IGlar. The rate of overall confirmed hypoglycaemia was significantly higher for IDegAsp [estimated rate ratio 1.43, 95% CI 1.07, 1.92; P < 0.05 (Fig. 3a)]. Nocturnal confirmed hypoglycaemia was reported in 19.1% (n = 44) and 21.0% (n = 49) of participants on IDegAsp and IGlar, respectively. Although fewer nocturnal hypoglycaemic events were reported in the IDegAsp group, the difference was not statistically significant [estimated rate ratio 0.80, 95% CI 0.49, 1.30; not significant (Fig. 3b)]. No participants on IDegAsp reported severe hypoglycaemia. Three participants (1.3%) on IGlar reported a total of four severe hypoglycaemic episodes.

Figure 3.

(a) Confirmed hypoglycaemia over 26 weeks for insulin degludec/insulin aspart (IDegAsp) once daily and insulin glargine (IGlar) once daily). (b) Nocturnal confirmed hypoglycaemia over 26 weeks for IDegAsp once daily and IGlar once daily. ERR, estimated rate ratio.

Hypoglycaemic episodes with IDegAsp were evenly spread throughout the day, with a trend towards a higher rate in the evening (20.00–24.00 h). In contrast, with IGlar the rate was higher from late night to early morning (04.00–08.00 h).

Post‐hoc analyses assessed the effect of switching participants on a high total dose of basal insulin at baseline (≥ 40 U) 1:1 to IDegAsp once daily. Scatter plots showed that the total basal insulin dose at baseline was not associated with an increased rate of hypoglycaemia during the first 4 weeks after switching (Fig. S1).

Adverse events

The incidence of treatment‐emergent AEs was similar for both IDegAsp once daily (57.8%, n = 133) and IGlar once daily (62.7%, n = 146); most AEs were mild to moderate. The most commonly reported AEs in both groups were nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, diarrhoea and peripheral oedema. One participant was withdrawn from the trial before completing 12 weeks of treatment because of an AE (haemorrhage). This participant had been randomized to the IGlar treatment arm and received treatment for 3.7 weeks. SAEs were reported in 4.3% (n = 10) of participants on IDegAsp and 3.4% (n = 8) of participants on IGlar. No deaths occurred during the trial. One SAE (hypoglycaemia; IGlar) was considered possibly related to the investigational product by the investigator. The participant recovered from this event.

Discussion

The present comparative treat‐to‐target trial in participants with Type 2 diabetes confirmed that IDegAsp once daily is non‐inferior to IGlar once daily in the reduction of HbA1c from baseline, as would be expected in a treat‐to‐target trial. Both treatments were well tolerated. There was no statistically significant difference in nocturnal hypoglycaemia between treatment groups, although there were fewer nocturnal hypoglycaemic events with IDegAsp, possibly as a result of the flat and stable action of the basal component of IDegAsp. IDegAsp once daily was associated with higher rates of overall confirmed hypoglycaemia compared with IGlar once daily, which may be related to the difference in timing of the hypoglycaemic events. With IDegAsp once daily, hypoglycaemic events were evenly distributed throughout the day, with a trend towards a higher rate in the evening (20.00–24.00 h) when the majority of subjects receiving IDegAsp were dosed alongside their main evening meal (65% of subjects). In contrast, with IGlar once daily the rate was higher from late night to early morning (04.00–08.00 h). This higher rate may be explained by the pharmacodynamic variability of IGlar vs that of the basal component of IDegAsp; in particular, within‐subject variability must be considered, which has been reported to be higher with IGlar and increases substantially 8 h post‐dosing 17.

These differences in timing suggest that the higher rate of overall hypoglycaemic events seen with IDegAsp could be attributed to the increased daytime effects of the bolus component, rather than the basal component, while the lower rate of overall hypoglycaemic events observed with IGlar could be attributed to its basal component.

While the addition of prandial insulin may lead to an increase in daytime hypoglycaemia, the trial design and conduct of this study may have contributed to the relatively high rate of overall confirmed hypoglycaemia that was observed with IDegAsp. The protocol specified that IDegAsp was to be administered with the main evening meal (or largest meal of the day), with participants required to continue administering IDegAsp at the same meal throughout the trial; however, the timing of the largest meal of the day may vary over time, and hence, for some participants, on some days the dose of prandial insulin injected as part of IDegAsp could have triggered postprandial hypoglycaemia. The trial protocol may also account for the higher proportion of patients administering IGlar at an ‘other’ or ‘unknown’ meal, as participants in the IGlar group were advised to administer insulin according to approved label instructions, which may vary day to day based on subject lifestyle and preference.

Furthermore, as the participants were instructed to titrate their insulin dose according to their mean pre‐breakfast glucose level, the increase in dose of IDegAsp once daily to achieve the pre‐breakfast target also inadvertently increased the dose of the prandial insulin (IAsp) component in IDegAsp, which, in turn, may have contributed to higher rates of hypoglycaemia, if the size and association with the meal were not considered. These results highlight the importance of adjusting prandial insulin doses with the actual size of the meal consumed, whilst also considering evening glucose values, which will also have an impact on the decision to uptitrate the IDegAsp dose.

In a real‐life setting participants are more likely to adjust the injection time and/or dose to match day‐to‐day changes in eating and/or activity than they are when following a strictly defined study protocol, and as they become more familiar with a combination of insulins. Hence, the difference in overall hypoglycaemia between the two regimens may be lower in the real‐life setting.

In a separate phase III, 26‐week, open‐label, treat‐to‐target trial of IDegAsp once daily in insulin‐naïve Japanese participants, IDegAsp once daily dosed at the largest meal provided superior glycaemic control, with significantly greater HbA1c reduction and similar improvements in FPG as well similar rates of overall and nocturnal hypoglycaemia, compared with IGlar 18. It could be speculated that Japanese eating patterns, in terms of meal size and timing, are more consistent from day to day, contributing to improved outcomes despite the inability to adjust injection time to match changes in diet. These findings highlight the importance of choosing and administering IDegAsp with the appropriate meal of the day to address the needs for prandial insulin coverage and to benefit from the characteristics of IDeg as basal insulin.

The study design may have had a strong impact on the results; specifically, on the rate of overall confirmed hypoglycaemia and nocturnal confirmed hypoglycaemia. The study protocol mandated a specific dosing time for IDegAsp administration and, as is the case with many clinical trials, may not be entirely reflective of real‐life practices of insulin administration. As such, in real life, dosing times are likely to change depending on the dietary and daily routines of participants. As in any open‐label trial, there may be a risk of underlying reporting bias. Investigators are likely to be more alert when treating subjects with a new insulin medical entity, such as IDegAsp, and subjects may be more hesitant towards a new treatment, for fear of hypoglycaemia or other side effects associated with treatment.

In conclusion, the results of this treat‐to‐target trial in insulin‐experienced participants with advanced Type 2 diabetes showed that IDegAsp once daily effectively improves glycaemic control and is non‐inferior to IGlar once daily in terms of reducing HbA1c. Flexibility in the injection time together with changes in dose to match any significant day‐to‐day changes in eating patterns should be considered when using IDegAsp dosed once daily to minimize the risk of postprandial hypoglycaemia.

Funding sources

This study was funded by Novo Nordisk A/S, Denmark (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01045447, EudraCT number: 2008‐005767‐34), which was also responsible for the design, analysis and reporting of the study, with input from the authors.

Competing interests

H.C.J. has received payments in the capacity of advisory panel member for Novo Nordisk. S.K. was involved in the Novo Nordisk clinical trial for IDeg. N.G.D. has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. L.E. and T.V.S. are employees and shareholders of Novo Nordisk. B.B. has received research and grant support (fully dedicated to Atlanta Diabetes Associates), consulting fees, speaker honoraria from Janssen, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi and Valeratas; research and grant support from Abbott, DexCom, Lexicon and Lilly, and speaker honoraria from Astra Zeneca and Merck.

Supporting information

Table S1 Predefined titration algorithm for insulin dose.

Figure S1 Scatter plot to assess correlation of total basal insulin dose (≥ 40 U) at baseline vs hypoglycaemia rates at week 4.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the participants who took part in the study and ApotheCom ScopeMedical, UK, for medical writing support, funded by Novo Nordisk. All authors were involved in the conception and design or analysis and interpretation of data of this trial, contributed to writing of the discussion, reviewed and edited and revised this manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

Diabet. Med. 34, 180–188 (2017)

References

- 1. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, Diamant M, Ferrannini E, Nauck M et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient‐centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2012; 35: 1364–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group . Intensive blood‐glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet 1998; 352: 837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ohkubo Y, Kishikawa H, Araki E, Miyata T, Isami S, Motoyoshi S et al. Intensive insulin therapy prevents the progression of diabetic microvascular complications in Japanese patients with non‐insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus: a randomized prospective 6‐year study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1995; 28: 103–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holman RR, Farmer AJ, Davies MJ, Levy JC, Darbyshire JL, Keenan JF et al. Three‐year efficacy of complex insulin regimens in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 1736–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Kruger DF, Travis LB. Correlates of insulin injection omission. Diabetes Care 2010; 33: 240–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vijan S, Hayward RA, Ronis DL, Hofer TP. Brief report: the burden of diabetes therapy: implications for the design of effective patient‐centered treatment regimens. J Gen Intern Med 2005; 20: 479–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ligthelm RJ, Gylvin T, DeLuzio T, Raskin P. A comparison of twice‐daily biphasic insulin aspart 70/30 and once‐daily insulin glargine in persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled on basal insulin and oral therapy: A randomized, open‐label study. Endocr Pract 2011; 17: 41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Strojek K, Bebakar WMW, Khutsoane DT, Pesic M, Smahelová A, Thomsen HF et al. Once‐daily initiation with biphasic insulin aspart 30 versus insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with oral drugs: an open‐label, multinational RCT. Curr Med Res Opin 2009; 25: 2887–2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Evans M, Schumm‐Draeger PM, Vora J, King AB. A review of modern insulin analogue pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles in type 2 diabetes: improvements and limitations. Diabetes Obes Metab 2011; 13: 677–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cengiz E, Swan KL, Tamborlane WV, Sherr JL, Martin M, Weinzimer SA. The Alteration of Aspart Insulin Pharmacodynamics When Mixed With Detemir Insulin. Diabetes Care 2012; 35: 690–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Havelund S. Insulin degludec (IDeg) and insulin aspart (IAsp) can be coformulated such that the formation of IDeg multi‐hexamers and IAsp monomers is retained upon subcutaneous injection. Presented at the American Diabetes Association, 21–25 June 2013, Chicago, USA (Poster 945‐P).

- 12. Heise T, Nosek L, Roepstorff C, Chenji S, Klein O, Haahr H. Distinct prandial and basal glucose‐lowering effects of insulin degludec/insulin aspart (IDegAsp) at steady state in subjects with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Ther Res Treat Educ Diabetes Relat Disord 2014; 5: 255–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Garber AJ, Ligthelm R, Christiansen JS, Liebl A. Premixed insulin treatment for type 2 diabetes: analogue or human? Diabetes Obes Metab 2007; 9: 630–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Christiansen JS, Liebl A, Davidson JA, Ligthelm RJ, Halimi S. Mid‐ and high‐ratio premix insulin analogues: potential treatment options for patients with type 2 diabetes in need of greater postprandial blood glucose control. Diabetes Obes Metab 2010; 12: 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fulcher GR, Christiansen JS, Bantwal G, Polaszewska‐Muszynska M, Mersebach H, Andersen TH et al. Comparison of insulin degludec/insulin aspart and biphasic insulin aspart 30 in uncontrolled, insulin‐treated type 2 diabetes: a phase 3a, randomized, treat‐to‐target trial. Diabetes Care 2014; 37: 2084–2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaneko S, Chow F, Taneda S, Park Y. Insulin degludec/insulin aspart versus biphasic insulin aspart 30 in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on basal or pre‐/self‐mixed insulin: A 26‐week, randomised, treat‐to‐target trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2015; 107: 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heise T, Hermanski L, Nosek L, Feldman A, Rasmussen S, Haahr H. Insulin degludec: four times lower pharmacodynamic variability than insulin glargine under steady‐state conditions in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2012; 14: 859–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Onishi Y, Ono Y, Rabøl R, Endahl L, Nakamura S. Superior glycaemic control with once‐daily insulin degludec/insulin aspart versus insulin glargine in Japanese adults with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with oral drugs: a randomized, controlled phase 3 trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 2013; 15: 826–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Predefined titration algorithm for insulin dose.

Figure S1 Scatter plot to assess correlation of total basal insulin dose (≥ 40 U) at baseline vs hypoglycaemia rates at week 4.