Abstract

A mini-Tn5Cm insertion has been identified that significantly reduced the amount of an extracellular activating signal for a lacZ fusion (cma37::lacZ) in Providencia stuartii. The transposon insertion was located immediately upstream of an open reading frame encoding a putative CysE ortholog. The CysE enzyme, serine acetyltransferase, catalyzes the conversion of serine to O-acetyl-l-serine (OAS). This activating signal was also produced by Escherichia coli, and production was abolished in a strain containing a null allele of cysE. Products of the CysE enzyme (OAS, N-acetyl-l-serine [NAS], O-acetyl-l-threonine, and N-acetyl-l-threonine) were individually tested for the ability to activate cma37::lacZ. Only OAS was capable of activating the cma37::lacZ fusion. The ability of OAS to activate the cma37::lacZ fusion was abolished by pretreatment at pH 8.5, which converts OAS to NAS. However, the activity of the native signal in conditioned medium was not decreased by treatment at pH 8.5. In contrast, conditioned medium prepared from cells grown at pH 8.5 exhibited a 4- to 10-fold-higher activity, relative to pH 6.0. Additional genes regulated by the CysE-dependent signal and OAS were identified in P. stuartii and E. coli. The response to the extracellular signal in E. coli was dependent on CysB, a positive activator that requires NAS as a coactivator. In E. coli, a cysE mutant formed biofilms at an accelerated rate compared to the wild type, suggesting a physiological role for this extracellular signal.

Cell-to-cell communication in bacteria is mediated by a wide variety of distinct chemical signals, and a number of reviews on this subject have been compiled (11, 12, 17, 22). In gram-negative bacteria, these signals include the N-acylhomoserine lactones, autoinducer 2 (AI-2), quinolones, cyclic dipeptides, and the tryptophan derivative indole (2, 12, 26, 32, 38). In gram-positive bacteria, peptides are the primary mode of communication (11, 17, 22). Although peptide-mediated signals have not been isolated from gram-negative bacteria, recent data suggest that such systems are present (13, 29, 30).

Several extracellular signals have been identified in Escherichia coli. Indole, a product of the tryptophanase-mediated catabolism of tryptophan, is capable of activating the astD, tnaB, and gabT genes (38). Studies using a tnaA mutant unable to produce indole have indicated that a second signal is required for full activation of the astD and gabT genes (38). A second signal in E. coli, the AI-2 furanone signal, has been shown by microarray analysis to control the expression of a large number of genes in E. coli (8, 34). Additional genes in E. coli that are regulated by undefined extracellular signals include rpoS, sdiA, cysK, and ftsQAZ (1, 14, 23, 33, 37).

The cysteine regulon in E. coli comprises a set of genes involved in the biosynthesis of cysteine from l-serine (18, 19). These genes are positively controlled by the CysB activator in concert with the molecule N-acetyl-l-serine (NAS) (19). The production of NAS occurs in two steps. First, serine is converted to O-acetyl-l-serine (OAS) by the CysE enzyme (serine acetyltransferase). OAS then undergoes a spontaneous acyl rearrangement to form NAS, a reaction favored at a pHs above 7.0 (18).

This paper reports that CysE is required in both Providencia stuartii and E. coli for the production of an extracellular signal that activates genes in both organisms. A product of the CysE reaction, OAS, can activate a subset of lacZ fusions to genes previously identified as being activated by cell-to-cell signaling. OAS and other cysteine metabolites can accumulate extracellularly in E. coli supernatants (5). However, this study demonstrates that although OAS can act as an activating signal, the actual signal in conditioned medium is unlikely to be either OAS or NAS and may represent a novel signal. Furthermore, we report that under our experimental conditions, a cysE mutant of E. coli formed biofilms at an accelerated rate relative to the wild type, suggesting a physiological role for CysE in controlling biofilm development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

P. stuartii strain XD37 has been described previously and contains a lacZ fusion (cma37) that is strongly activated by an extracellular signal (30). E. coli strains XL1 (Stratagene), CC118 λpir, and SM10 λpir were used as hosts for transformations and plasmid propagations. E. coli S17.1 pUT::mini-Tn5Cm was used for transposon mutagenesis (9). Conditioned medium was prepared as described previously (30). NAS and OAS were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. and prepared in Luria broth (LB) immediately before use. Solutions were adjusted to the designated pH by the addition of NaOH. O-Acetyl-l-threonine (OAT) was prepared as a custom synthesis (Bachem). β-Galactosidase assays were performed with sodium dodecyl sulfate-chloroform-permeabilized cells as described previously (30).

Isolation of the pef::mini-Tn5Cm insertion.

Chromosomal DNA from XD38 was digested with XbaI, which does not cut within mini-Tn5Cm, and probed using a 3.6-kb fragment of the chloramphenicol resistance gene from mini-Tn5Cm (9). A single hybridizing band of 10 kb was identified. To clone this fragment, XbaI-digested chromosomal fragments in the range of 8 to 12 kb were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and a glass milk procedure (Bio 101) and these fragments were ligated to pACYC184Δ1 digested with XbaI. pACYC184Δ1 is a derivative of pACYC184 in which an EcoRI-ScaI fragment has been removed to inactivate the chloramphenicol resistance gene. Ligation mixes were electroporated into XL1, and plasmids containing the appropriate insert were identified by chloramphenicol resistance and desigated pACYC184.37-3. To clone a segment of P. stuartii chromosomal DNA flanking the insertion site, pACYC184.37-3 was digested with XbaI and EcoRI and a 1.6-kb flanking segment was cloned into pBCKS (Stratagene) cut with the same enzymes. Sequence analysis of this fragment was performed using the T3 and T7 primers.

P. stuartii pef::mini-Tn5Cm allelic replacement.

To reconstruct the pef::mini-Tn5Cm mutation in a fresh XD37 background, the 10-kb XbaI fragment from pACYC184.37-3 was transferred as a XbaI fragment to the suicide vector pKNG101 (16) to create pKNG101.37-3. A plate mating between SM10 pKNG101.37-3 and P. stuartii XD37 was used to introduce pKNG101.37-3 into the chromosome of XD37 by homologous recombination. Excision of the plasmid with the resulting pef::mini-Tn5Cm insertion was carried out using sucrose selection and screening for chloramphenicol resistance.

Construction of an E. coli cysE mutant in the MG1655 and W3110 backgrounds.

To isolate the E. coli cysE gene, a plasmid library of E. coli chromosomal fragments in pET21a (provided by Piet deBoer) was electroporated into XD38 (pef::mini-Tn5Cm). Colonies with restored expression of lacZ from the cma37::lacZ fusion were identified on 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) plates. Plasmids from these colonies were sequenced at one end using the T7 primer. The plasmids contained overlapping fragments from the cysE region, including the cysE gene. To disrupt the cysE gene, a unique ClaI site centrally located within the cysE gene was blunt ended with T4 DNA polymerase followed by religation. Loss of the ClaI site was verified both by restriction digestion and by the inability of this plasmid to restore cma37::lacZ expression in XD38. A XbaI-XhoI fragment containing the disrupted cysE gene and flanking DNA was cloned into pKNG101 (16) cut with XbaI and SalI to create pKNG101.ΔcysE. This plasmid was electroporated into E. coli MG1655 or W3110, and streptomycin-resistant transformants were selected. Resolution of the integrated plasmid on sucrose plates gave two distinct sizes of colonies. The smaller, dome-shaped colonies all contained the cysE mutation as determined by Southern blot analysis. As expected, these small colonies were all cysteine auxotrophs.

Construction of a cysB mutant.

The one-step allelic replacement procedure described by Datsenko and Wanner was used to disrupt the cysB gene (6). A PCR product was generated using the primers 5′-AAATTACAACAACTTCGCTATATTGTTGAGGTGGTCAAGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTG-3′ and 5′-AGTTTTATATCTTTAAACATGACCTCAATTTCTTCATTAGCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG-3′ on the template plasmid pKD3 containing a chloramphenicol resistance gene. Strain RM1734/pKD46 was grown in the presence of 1 mM arabinose and used as the host strain for electroporation of PCR products. PCR analysis using primers that amplify the cysB coding region was used to confirm the cysB::cat disruption.

Construction of the fimH and wcaF mutants.

The fimH::cat and wcaF::cat mutations were introduced in MG1655 (with or without cysE) and W3110 (with or without cysE) by P1 transduction using phage lysates prepared from ZK2695 (fimH::cat) and ZK2687 (wcaF::cat). The presence of the mutations on the chromosome was checked by PCR.

Growth and analysis of biofilms.

Biofilm formation in microtiter dishes was measured as described previously (24, 25). Microtiter wells were inoculated from overnight LB-grown cultures diluted 1:50 in M63 medium [12 g of KH2PO4 per liter, 28 g of K2HPO4 per liter, 8 g of (NH4)2SO4 per liter] supplemented with 1 mM MgSO4, 0.2% glucose (Glc), and 0.5% Casamino Acids. The cells were grown for 24 hr at 30°C before being stained with crystal violet and quantified as described by O'Toole and Kolter (24). For biofilms grown under flow conditions, bacteria were cultivated in flow chambers with channel dimensions of 5 by 1 by 30 mm. The flow system was assembled as described previously (3). The flow cell was inoculated from overnight LB-grown cultures diluted 10-fold in modified EPRI medium (50 mg of NaSO4 per liter, 0.91 g of KH2PO4 per liter, 0.63 g of K2HPO4 per liter, 50 mg of NH4NO3 per ml, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.04% Glc, 0.05% Casamino Acids). The medium flow was turned off prior to inoculation and for 1 h after inoculation. Thereafter, medium was pumped through the flow cell at a constant rate (1.8 ml/h) for the duration of the experiment. The flow was controlled with a PumpPro MPL (Watson-Marlow). Images were acquired with a DM IRB inverted microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a cooled charge-coupled-device digital camera, and a 63× PL FLOTAR objective lens was used for phase-contrast microscopy. Digital images were captured and analyzed using OpenLab software (Improvision, Coventry, England).

To assay the biofilm phenotype in the presence of OAS and cysteine, microtiter plates were inoculated with medium containing OAS (10 mM) or cysteine (100 μM). In all cases, the pH of the medium was adjusted to 7.

Complementation assays.

MG1655 and W3110, as well as the cysE mutants in these two backgrounds, were transformed by electroporation with either the control vector pET21a (Novagen) or pET21a-cysE and plated on LB plus ampicillin (150 μg/ml). Complementation assays in flow cells were done with modified EPRI that was not supplemented with ampicillin because we found that pET21a was stable for several days in the absence of selection under these conditions.

RESULTS

Previous work identified a lacZ fusion (cma37::lacZ) in P. stuartii that was strongly activated by the accumulation of an extracellular molecule in conditioned medium (30). To identify genes involved in production of this signal, mini-Tn5Cm was used to mutagenize P. stuartii XD37 cma37::lacZ. An insertion with decreased expression of cma37::lacZ was identified as a colony with decreased blue color on plates containing the β-galactoidase indicator X-Gal. This mutant was designated XD38. To test for signal production, conditioned medium was prepared from XD38 and wild-type XD37 cells at an optical density at 600 nm of 1.1, representing early stationary phase. The ability of each conditioned medium to activate the cma37::lacZ fusion in cells at early log phase was investigated. With conditioned medium from XD37 (wild type), the cma37::lacZ fusion was activated 20-fold (Table 1). However, conditioned medium from XD38 activated the cma37::lacZ fusion eightfold. As a control, another P. stuartii fusion (cma227::lacZ) previously shown to be activated by cell-to-cell signaling (30) was activated threefold in conditioned medium from XD37 and fourfold in conditioned medium from XD38. This mutant, XD38, contained a mutation designated pef::mini-Tn5Cm (Providencia extracellular factor).

TABLE 1.

Ability of conditioned medium to activate the cma37::lacZ fusion in early-log-phase cells

| Source of medium | Relative activation of cma37::lacZa |

|---|---|

| P. stuartii XD37 (wild type) | 20 ± 1.0 |

| P. stuartii XD38 (cysE1::mini-Tn5Cm) | 8 ± 0.8 |

| E. coli MG1655 (wild type) | 28 ± 4.7 |

| E. coli MG1655-C (ΔcysE1) | 3 ± 0.1 |

Values represent the fold activation relative to cells grown in LB only.

Identification of the pef mutation.

The location of the mini-Tn5Cm insertion in XD38 was determined as described in Materials and Methods. The insertion was 80 bp upstream of a potential ATG start codon for a putative open reading frame of which the first 273 bp were sequenced. The first 91 amino acids encoded by this open reading frame aligned with amino acids 1 to 91 of the E. coli CysE protein and exhibited 71% amino acid identity over this region (10). The location of the mini-Tn5Cm insertion suggested that it may interfere with transcription of cysE. Consistent with this, XD38 cells exhibited a cysteine auxotrophy (data not shown).

To confirm that the mini-Tn5Cm insertion was responsible for decreased signal production, the pef::mini-Tn5Cm mutation was reconstructed in a fresh XD37 background by allelic replacement (see Materials and Methods). The reconstructed pef::mini-Tn5Cm mutants exhibited the same phenotypes as the original mutant.

E. coli produces a CysE-dependent extracellular signal that activates cma37::lacZ in P. stuartii.

The cysE gene is also present in E. coli (10), and conditioned medium from E. coli MG1655 was tested for the ability to activate the cma37::lacZ fusion (Table 1). The cma37::lacZ fusion was activated 28-fold by conditioned medium from E. coli MG1655. To examine the role of CysE in the production of this signal, a null allele of cysE was constructed in E. coli and designated MG1655-C (ΔcysE). Conditioned medium from MG1655-C exhibited an 88% decline in the ability to activate the cma37::lacZ fusion in P. stuartii relative to wild-type conditioned medium (Table 1). Therefore, a cysE-dependent extracellular signal is produced by both P. stuartii and E. coli. A mutation in cysK, which blocks the next and final step in cysteine biosynthesis, did not significantly alter the production or activity of the extracellular signal, nor did the product of CysK (cysteine) have any activity on the cma37::lacZ fusion (data not shown).

OAS can act as an extracellular activating signal.

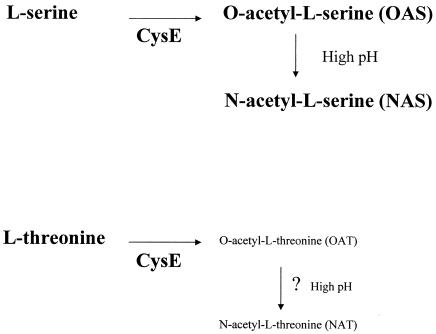

The CysE enzyme catalyzes the conversion of l-serine to OAS (Fig. 1). OAS can undergo a spontaneous acyl migration at pH 7.5 and above to form NAS (18). In addition, the CysE enzyme can convert l-threonine to OAT at low efficiency (18). We reasoned that OAT may be converted to N-acetyl-l-threonine (NAT) at pH 8 by an acyl migration similar to that which occurs for OAS. Therefore, all four compounds were tested at different amounts (0.1 to 20 mM) and at pH values of 6, 7, and 8 for the ability to activate cma37::lacZ. The only molecule capable of activation was OAS, and the ability to activate was significantly higher at pH 6 and 7 than at pH 8 (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Products of the CysE enzyme. The known substrates and products of the CysE enzyme are depicted. OAT is proposed to be a minor product of the CysE enzyme.

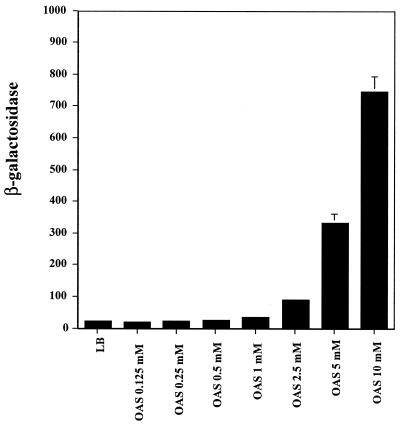

In Fig. 2, the effects of various concentrations of OAS on the expression of cma37::lacZ at pH 7 is shown. Activation of cma37::lacZ began at an OAS concentration of 2.5 mM (4-fold activation) and reached activation levels of 46-fold at 10 mM (Fig. 2). To determine if the activity of OAS was decreased by high pH, we incubated LB containing 5 mM OAS at pH 3.0 or 8.5 for 3 h. Each preparation was then adjusted to pH 7.0 and used to grow XD37 cells. The medium with OAS preexposed at pH 3.0 gave five-fold activation of cma37::lacZ with 64 ± 0.3 Miller units of β-galactosidase, relative to the 14 ± 0.1 Miller units in LB-only medium. In contrast, the LB medium plus OAS exposed at pH 8.5 resulted in 11 ± 0.6 Miller units from the cma37::lacZ fusion.

FIG. 2.

Activation of cma37::lacZ by OAS. P. stuartii XD37 (cma37::lacZ) was grown in 0.5× LB (pH 7.5) and 0.5× LB + OAS (pH 7.5) at concentrations ranging from 0.125 to 10 mM. A mid-log-phase culture of XD37 cells was used to inoculate 3-ml cultures, and the cells were shaken for 2 h at 37°C before being harvested. The expression of β-galactosidase was determined in SDS-chloroform-permeabilized cells. Values represent the average of duplicate samples. This experiment was repeated three times, with similar results.

OAS can activate additional extracellular factor-activated lacZ fusions in P. stuartii and E. coli.

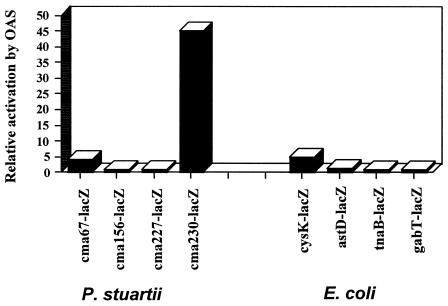

Previous work has identified lacZ fusions in P. stuartii that were activated by the accumulation of self-produced extracellular signals (30). The cma37::lacZ fusion is within a putative metI homolog involved in dl-methionine uptake, cma67::lacZ is within a cysK homolog, cma156::lacZ is within a putative dicarboxylate transporter, and both cma227::lacZ and cma230::lacZ are within genes of unknown function (30). The ability of OAS to activate these fusions was examined. The cma67::lacZ and cma230::lacZ fusions were activated 4- and 45-fold, respectively, at a OAS concentration of 4 mM (Fig. 3). The cma156::lacZ and cma227::lacZ fusions were not significantly activated by OAS (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Effect of OAS on previously identified lacZ fusions in P. stuartii and E. coli. Previous fusions that were identified as activated by cell-cell signaling were tested for activation by 4 mM OAS. Values represent the average of duplicate samples, with repeated experiments giving similar results.

The ability of OAS to activate E. coli fusions previously shown to be activated by extracellular signals was also investigated (1). The cysK::lacZ fusion was activated five-fold by OAS. However, lacZ fusions to the astD, tnaB, and gabT genes were not altered by OAS (1) (Fig. 3).

pH effects on signal activity in conditioned medium.

Conditioned medium was prepared from E. coli MG1655 cells grown in LB at pH 6.0 or 8.5 to an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0, representing early stationary phase. The culture pH after growth was typically 6.5 to 6.6 for the pH 6.0 culture and 8.2 to 8.3 for the pH 8.5 culture. Under these conditions, OAS should be stable at pH 6 and unstable at pH 8.5, where it would be converted to NAS (17). Each conditioned medium was then brought to the same pH (pH 7.5) and tested for activation of various lacZ fusions in P. stuartii. Unexpectedly, the conditioned medium prepared from cells grown at pH 8.5 exhibited a 4- to 10-fold increase in activity relative to pH 6 based on the ability to activate the cma37, cma67, and cma230 fusions (Table 2). The ability of high pH to increase the signal activity was completely dependent on a functional CysE, as was the activity observed in the pH 6.0 culture (Table 2). One possible explanation for the pH-dependent production of the activating signal is that cysE mRNA accumulates at higher levels at pH 8.5. However, Northern blot analysis of cysE mRNA under each set of conditions did not reveal any significant differences in mRNA accumulation (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Activation of lacZ fusions by conditioned medium

| Conditioned medium | Relative activationa of P. stuartii lacZ fusion:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| cma37 | cma67 | cma230 | |

| MG1655 (pH 6) | 5 ± 0.3 | 4 ± 0.3 | 8 ± 0 |

| MG1655 (pH 8.5) | 54 ± 3.5 | 14 ± 0.6 | 74 ± 5 |

| MG1655-C ΔcysE (pH6) | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| MG1655-C ΔcysE (pH8.5) | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0 |

Values represent the fold activation relative to cells grown in LB only.

Role of cysB in the activation of cysK::lacZ by OAS or conditioned medium.

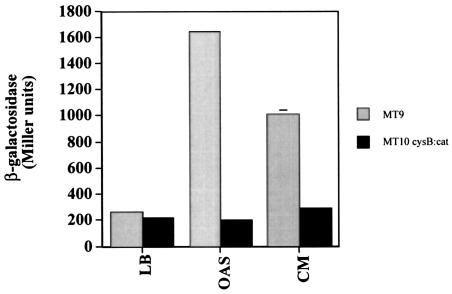

The E. coli cysteine regulon is activated by the CysB protein in concert with NAS, which acts as a coactivator (19). Since the E. coli cysK::lacZ fusion has been previously shown to be activated by both conditioned medium (1) and OAS (Fig. 3), we investigated the role of CysB in this activation. A cysB::cat null allele prevented the activation of cysK::lacZ in response to both OAS and conditioned medium (Fig. 4). The role of CysB in the activation of cysK has been clearly documented previously (19). However, the finding that CysB is also required for the response to both OAS and a signal in conditioned medium was surprising, given that a role for a secreted OAS-like compound in cell signaling has not been reported.

FIG. 4.

Activation of cysK::lacZ in wild-type and cysB::cat backgrounds. Cells of MT9 cysK::lacZ or MT10 cysK::lacZ, cysB::cat were grown in LB, LB plus 10 mM OAS, or conditioned medium (CM) harvested from cells at an optical density of 1.1. Cells were harvested at an optical density of 0.35, and β-galactosidase was assayed as described previously (30). The reported values represent the average of quadruplicate samples from two independent experiments.

Role of CysE in E. coli biofilm development.

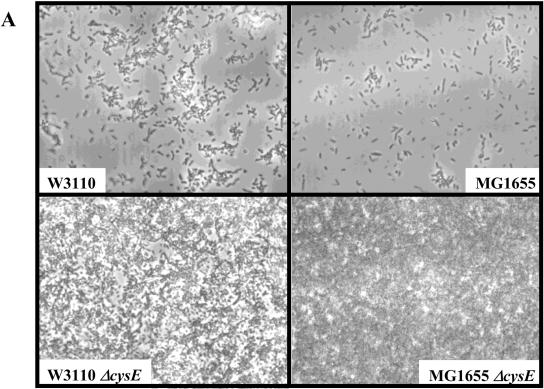

Extracellular signaling plays a role in biofilm development in diverse bacteria (7, 15, 20, 21). Therefore, biofilm formation in the E. coli cysE mutant was investigated. The ΔcysE mutant in the MG1655 strain background was tested for its ability to form biofilms, and results of flow cell and 96-well plate assays showed that the ΔcysE cells attach to abiotic surfaces (glass or polyvinyl chloride) to a greater degree than does the wild type (Fig. 5). In a flow cell assay, after only 3 h of incubation at 30°C in a minimal EPRI medium, the ΔcysE cells covered significantly more of the glass surface than the wild type did, and by 24 h a thick biofilm was seen for ΔcysE whereas very few wild-type cells are attached at this time point (Fig. 5A).

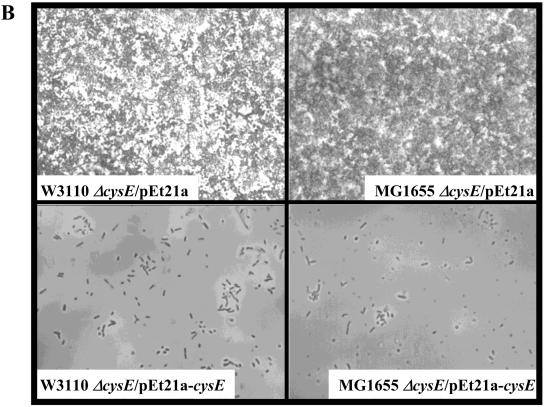

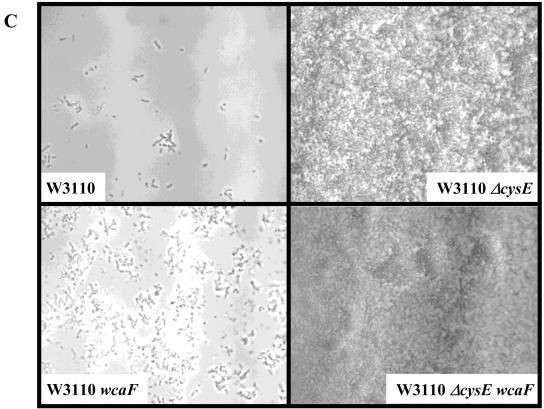

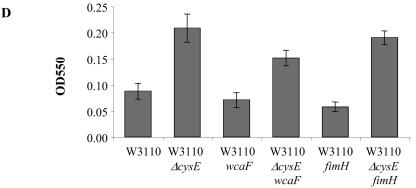

FIG. 5.

Role for cysE in biofilm development. (A to C) Phase-contrast micrographs are top-down views from flow cell experiments after an incubation for 24 h at 30°C in modified EPRI medium. (A) the ΔcysE mutation confers a hyperbiofilm phenotype in both the MG1655 and W3110 backgrounds. (B) The ΔcysE phenotype can be complemented in flow cells by introducing the multicopy plasmid pET21a carrying a wild-type copy of cysE. (C and D) The ΔcysE phenotype is independent of the pili as well as the colanic acid synthesis pathways as assessed in flow cell and microtiter dish assays. (C) Introduction of the wcaF::cat mutation does not affect the hyperbiofilm phenotype of the ΔcysE mutant strain. (D) Quantification of microtiter dish assays. Neither the fimH::cat nor the wcaF::cat mutation affected the hyperbiofilm phenotype of the ΔcysE mutant strain. OD550, optical density at 550 nm.

Motility assays show that MG1655 is slightly defective for flagellar swimming whereas the ΔcysE mutant is capable of flagellar motility. Therefore, it was possible that the hyperbiofilm phenotype observed was due to this difference in motility. To address this question, we decided to test ΔcysE in the W3110 genetic background. The W3110 strain is known to be motile and to form biofilms under a variety of conditions (4, 27). As shown in Fig. 5A, the same hyperbiofilm phenotype can be observed in the ΔcysE mutant background, suggesting that CysE plays a role in biofilm development independent of motility or the genetic background tested.

To ensure that the observed phenotype was due to the lack of CysE function, we introduced a pET21a derivative plasmid containing cysE under the control of its own promoter in both genetic backgrounds studied. Figure 5B shows that, in both cases, the presence of cysE in multicopy complemented the hyperbiofilm phenotype. The vector control (pET21a) had no effect on the biofilm formed by the ΔcysE mutant. Also, it appeared that providing CysE on a multicopy plasmid reduced biofilm formation by the wild type, suggesting that the effect of CysE could be dose dependent.

Previous work suggested that type I pili and colanic acid are important for the early attachment of the cells and stabilization of the biofilm structure, respectively (4, 27, 28). To determine if these functions played a role in the hyperbiofilm formation phenotype of the ΔcysE mutant, we introduced the fimH::cat or wcaF::cat mutation into this genetic background and assessed their biofilm formation phenotype. Biofilms were grown in 96-well plates as well as in flow cells. The presence of the fimH::cat or wcaF::cat mutations did not seem to decrease the cysE hyperbiofilm phenotype in either assay (Fig. 5C and D). The same observation could be made from either the MG1655 or W3110 background. These mutations also have little or no effect on biofilm formation in the medium used in these studies. Taken together, these data suggest that the hyperbiofilm formation phenotype of the ΔcysE mutant is independent of type I pili and colanic acid.

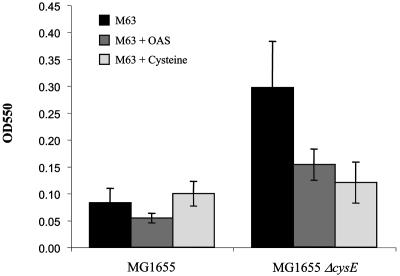

Effect of OAS and cysteine on biofilm formation in the presence or absence of CysE.

The previous data showed that cysE mutants formed biofilms at an accelerated rate compared to the wild type. This phenotype may arise due to the failure of cysE mutants to produce an extracellular signal that could serve to limit biofilm formation. To test this possibility, we investigated the effects of added OAS, which can mimic the extracellular signal at high concentrations (Fig. 2 and 3). Figure 6 shows that the addition of OAS to wild-type cells resulted in a slight inhibition of biofilm formation. However, in the cysE mutant, this inhibition was more pronounced, with a twofold reduction. Next, the effect of cysteine on biofilm development was examined. Excess cysteine is able to inhibit the CysE enzyme by a feedback mechanism. Therefore, in the presence of excess cysteine, CysE enzyme activity is decreased. The addition of 100 μM cysteine resulted in a slight enhancement of biofilm development in a wild-type background (Fig. 6). In a cysE mutant, the addition of cysteine reduced biofilm formation by 2.5-fold.

FIG. 6.

Effect of OAS and cysteine on biofilm formation. Biofilm formation by strains MG1655 and MG1655 ΔcysE is shown with no addition (M63) or the addition of OAS or cysteine. The data shown are from three independent biofilm assays performed in microtiter dishes. OD550, optical density at 550 nm.

DISCUSSION

In this study, a role for serine acetyltransferase (CysE) in the production of an extracellular signaling molecule has been identified in both P. stuartii and E. coli. The activity of the CysE enzyme results in four potential products, OAS, NAS, OAT, and NAT. Of these, only OAS was able to activate selected lacZ fusions in both P. stuartii and E. coli. However, the concentration of OAS required for activation was at least 2.5 mM (Fig. 3). Although this concentration is high relative to that of other signaling molecules, previous studies have indicated that OAS and NAS can accumulate at millimolar concentrations in the extracellular media of stationary-phase cultures (5). We estimated that, under our growth conditions, OAS accumulated to a concentration of 1 mM in LB maintained at a pH below 7.0 (data not shown). Since this concentration is lower than the concentration required for activation (2.5 mM and above), we do not think that OAS is the true activating signal.

OAS and conditioned medium were both capable of activating the cma37::lacZ reporter fusion. However, the pH requirements for activation were quite distinct for each condition. For example, activation by OAS required a pH of 7.0 or below and the ability to activate was destroyed at pH 8.5. This loss of activity at pH 8.5 was presumably due to the conversion of OAS to NAS by intramolecular acyl transfer. The possible involvement of NAS as a signal was ruled out since NAS did not display signal activity at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 20 mM (data not shown). In contrast, the activating signal in conditioned medium was stable at pH 8.5. Moreover, signal activity in conditioned medium was significantly enhanced at pH 8.5 compared to 7.0 (Table 2). These data, taken together, indicate that although the authentic signal in conditioned medium is dependent on CysE for production, the signal is unlikely to be either OAS or NAS.

What is the cysE-dependent activating signal in conditioned medium? Three possibilities are considered: (i) the signal is a derivative of OAS, possibly an N-O-diacetylated version of l-serine; (ii) the signal is an acetylated derivative of homoserine; or (iii) the signal is a small peptide that contains acetylated serine or threonine as one of the amino acids. The possible involvement of an acetylated peptide is supported by the observation that protease treatment of E. coli conditioned medium eliminated the ability to activate the cma37 fusion (data not shown). In addition, we have demonstrated that AarA, an intramembrane serine protease, is required to produce the activating signal for cma37::lacZ (30). AarA is a member of the rhomboid family of serine proteases that generate signaling molecules by regulated intramembrane proteolysis of other membrane-associated proteins (13, 35). The requirement for a serine protease (AarA) in signal generation suggests that the signal is a peptide. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the requirement for AarA is indirect.

In these studies we also provide one possible physiological role for the CysE-dependent signal. We showed that, in two different genetic backgrounds, E. coli lacking cysE produces a biofilm faster and with a great biomass than does wild-type strain. Interestingly, this phenotype is specific to cells grown at 30°C. The enhanced biofilm development in the cysE mutant was reduced in the presence of 10 mM OAS (Fig. 6). Unexpectedly, cysteine was also able to reduce the accelerated biofilm phenotype in a cysE background (Fig. 6). The basis for this reduction is unclear. A possible explanation is that cysteine, either intracellular or acting extracellularly, is the actual signal that inhibits biofilm development. Since cysteine had no effect on the lacZ fusions reported here, CysE may function in two pathways, one for the production of an extracellular signal and one that serves to limit biofilm development.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation awards 9904766 and 0406047 to P.N.R. and by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI051360) and the Pew Charitable Trusts to G.A.O. G.A.O. is a Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baca-DeLancey, R. R., M. M. South, X. Ding, and P. N. Rather. 1999. Escherichia coli genes regulated by cell to cell signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:4610-4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen, X., S. Shauder, N. Potier, A. Van Dorsselaer, I. Pelczer, B. L. Bassler, and F. M. Hughson. 2002. Structural identification of a bacterial quorum-sensing signal containing boron. Nature 415:545-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christensen, B. B., C. Sternberg, J. B. Andersen, R. J. Palmer, Jr., A. T. Nielsen, M. Givskov, and S. Molin. 1999. Molecular tools for study of biofilm physiology. Methods Enzymol. 310:20-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danese, P. N., L. A. Pratt, and R. Kolter. 2000. Exopolysaccharide production is required for development of Escherichia coli K-12 biofilm architecture. J. Bacteriol. 182:3593-3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daßler, T., T. Maier, C. Winterhalter, and A. Bock. 2000. Identification of a major facilitator protein from Escherichia coli involved in the efflux of metabolites of the cysteine pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 36:1101-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies, D. G., M. R. Parsek, J. P. Pearson, B. H. Iglewski, J. W. Costerton, and E. P. Greenberg. 1998. The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science 280:295-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLisa, M. P., C. F. Wu, L. Wang, J. J. Valdes, and W. E. Bentley. 2001. DNA microarray-based identification of genes controlled by autoinducer 2-stimulated quorum sensing in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:5239-5247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Lorenzo, V., M. Herrero, U. Jakubzik, and K. Timmis. 1990. Mini-Tn5 derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:6568-6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denk, D., and A. Bock. 1987. l-Cysteine biosynthesis in Escherichia coli: nucleotide sequence and expression of the serine acetyltransferase (cysE) gene from the wild-type and a cysteine-excreting mutant. J. Gen. Microbiol. 133:515-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunny, G. M., and B. A. Leonard. 1997. Cell-cell communication in gram-positive bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51:527-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuqua, C., S. C. Winans, and E. P. Greenberg. 1996. Census and consensus in bacterial ecosystems: the LuxR-LuxI family of quorum sensing transcriptional regulators. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:727-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallio, M., G. Sturgill, P. N. Rather, and P. Klysten. 2002. A conserved mechanism for extracellular signaling in eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:12208-12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.García-Lara, J., L. H. Shang, and L. I. Rothfield. 1996. An extracellular factor regulates expression of sdiA, a transcriptional activator of cell division genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 178:2742-2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huber, B., K. Riedel, M. Hentzer, A. Heydorn, A. Gotschlich, M. Givskov, S. Molin, and L. Eberl. 2001. The cep quorum-sensing system of Burkholderia cepacia H111 controls biofilm formation and swarming motility. Microbiology 147:2517-2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaniga, K., I. Delor, and G. Cornelis. 1991. A wide-host-range suicide vector for improving reverse genetics in Gram-negative bacteria: inactivation of the blaA gene of Yersinia enterocolitica. Gene 109:137-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleerebezem, M., L. E. N Quadri, O. P. Kuipers, and W. M. deVos. 1997. Quorum sensing by peptide pheromones and two-component signal transduction systems in gram positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 24:895-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kredich, N. M., and G. M. Tomkins. 1966. The enzymic synthesis of l-cyteine in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 241:4955-4965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kredich, N. M. 1996. Biosynthesis of cysteine, p. 515-527. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Raznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), E scherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 20.Lynch, M. J., S. Swift, D. F. Kirke, C. W. Keevil, C. E. Dodd, and P. Williams. 2002. The regulation of biofilm development by quorum sensing in Aeromonas hydrophila. Environ. Microbiol. 4:18-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merrit, J., F. Qi, S. D. Goodman, M. H. Anderson, and W. Shi. 2003. Mutation of luxS affects biofilm formation in Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 71:1972-1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller, M. B., and B. L. Bassler. 2001. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:165-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mulvey, M. R., J. Switala, A. Borys, and P. C. Loewen. 1990. Regulation of transcription of katE and katF in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 172:6713-6720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Toole, G. A., and R. Kolter. 1998. Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol. Microbiol. 30:295-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Toole, G. A., L. A. Pratt, P. I. Watnick, D. K. Newman, V. B. Weaver, and R. Kolter. 1999. Genetic approaches to the study of biofilms. Methods Enzymol. 301:91-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pesci, E. C., J. B. Milbank, J. P. Pearson, S. McKnight, A. S. Kende, E. P. Greenberg, and B. H. Iglewski. 1999. Quinolone signaling in the cell-to-cell communication system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:11229-11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pratt, L. A., and R. Kolter. 1998. Genetic analysis of Escherichia coli biofilm formation: roles of flagella, motility, chemotaxis and type-1 pili. Mol. Microbiol. 30:285-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prigenet-Combaret, C., G. Prensier, T. T. Le Thi, O. Vidal, P. Lejeune, and C. Dorel. 2000. Developmental pathway for biofilm formation in curli-producing Escherichia coli strains: role of flagella, curli and colanic acid. Environ. Microbiol. 2:450-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rather, P. N., M. M. Parojcic, and M. R. Paradise. 1997. An extracellular factor regulating expression of the chromosomal aminoglycoside 2′-N-acetyltransferase of Providencia stuartii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1749-1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rather, P. N., X. Ding, R. R. Baca-DeLancey, and S. Siddiqui. 1999. Providencia stuartii genes activated by cell-cell signaling and identification of a gene required for the production or activity of an extracellular factor. J. Bacteriol. 181:7185-7191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salmond, G. P. C., B. W. Bycroft, G. S. A. B. Stewart, and P. Williams. 1995. The bacterial enigma: cracking the code of cell-cell communication. Mol. Microbiol. 16:615-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schauder, S., K. Shokat, M. G. Surette, and B. L. Bassler. 2001. The LuxS family of bacterial autoinducers: biosynthesis of a novel quorum-sensing signal molecule. Mol. Microbiol. 41:463-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sitnikov, D. M., J. B. Schineller, and T. O. Baldwin. 1996. Control of cell division in Escherichia coli: regulation of transcription of ftsQA involves both rpoS and SdiA mediated autoinduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:336-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sperandio, V., A. G. Torres, J. A. Giron, and J. B. Kaper. 2001. Quorum sensing is a global regulatory mechanism in enterohemorragic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Bacteriol. 183:5187-5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urban, S., J. R. Lee, and M. Freeman. 2001. Drosophila rhomboid-1 defines a family of putative intramembrane serine proteases. Cell 107:173-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vance, R. E., J. Zhu, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2003. A constitutively active variant of the quorum sensing regulator LuxO affects protease production and biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 71:2571-2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang, X., P. A. J. deBoer, and L. I. Rothfield. 1991. A factor that positively regulates cell division by activating transcription of the major cluster of essential cell division genes of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 10:3363-3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang, D, X. Ding, and P. N. Rather. 2001. Indole can act as an extracellular signal in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:4210-4216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]