Abstract

Bap (biofilm-associated protein) is a 254-kDa staphylococcal surface protein implicated in formation of biofilms by staphylococci isolated from chronic mastitis infections. The presence of potential EF-hand motifs in the amino acid sequence of Bap prompted us to investigate the effect of calcium on the multicellular behavior of Bap-expressing staphylococci. We found that addition of millimolar amounts of calcium to the growth media inhibited intercellular adhesion of and biofilm formation by Bap-positive strain V329. Addition of manganese, but not addition of magnesium, also inhibited biofilm formation, whereas bacterial aggregation in liquid media was greatly enhanced by metal-chelating agents. In contrast, calcium or chelating agents had virtually no effect on the aggregation of Bap-deficient strain M556. The biofilm elicited by insertion of bap into the chromosome of a biofilm-negative strain exhibited a similar dependence on the calcium concentration, indicating that the observed calcium inhibition was an inherent property of the Bap-mediated biofilms. Site-directed mutagenesis of two of the putative EF-hand domains resulted in a mutant strain that was capable of forming a biofilm but whose biofilm was not inhibited by calcium. Our results indicate that Bap binds Ca2+ with low affinity and that Ca2+ binding renders the protein noncompetent for biofilm formation and for intercellular adhesion. The fact that calcium inhibition of Bap-mediated multicellular behavior takes place in vitro at concentrations similar to those found in milk serum supports the possibility that this inhibition is relevant to the pathogenesis and/or epidemiology of the bacteria in the mastitis process.

Genetic and physiological studies have revealed that multicellularity is a widespread behavior in bacteria. Microorganisms can live and proliferate as individual cells swimming freely in the environment (planktonic mode of growth), or they can grow as highly organized multicellular complexes known as bacterial films or biofilms (7). The initial attachment of planktonic bacteria to a solid surface, the subsequent proliferation and accumulation in multilayer cell clusters, and the final formation of the bacterial community enclosed in a self-produced polymeric matrix are sequential steps that give rise to a mature biofilm (43). Switching between planktonic and biofilm modes of growth is a tightly regulated process that implies extensive physiological changes in the bacteria, and it takes place in response to a variety of environmental factors (16).

Mutational studies allowed us to identify Bap (biofilm-associated protein), a staphylococcal surface protein, as a protein that is essential for biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus strain V329 (9). The bap gene is carried in a putative composite transposon inserted in SaPIbov2, a mobile staphylococcal pathogenicity island (49). This gene encodes a 2,276-amino-acid protein that has the multidomain architecture characteristic of surface-associated proteins from gram-positive bacteria (15, 17, 35). The N-terminal domain (819 amino acids) includes a signal sequence for extracellular secretion and for the most part is devoid of repetitions. The region encompassing residues 820 to 2148 is composed of 13 identical repeats, each of which is 86 amino acids long. These repetitions are predicted to fold into a seven-strand β-sandwich and likely belong to the HYR module, a new immunoglobulin-like fold involved in cellular adhesion (5). After this long repeat region Bap contains a sequence stretch rich in serine and aspartic acid residues resembling the SD repeats of the Sdr family of staphylococcal surface proteins (20). The C terminus of Bap contains a typical cell wall attachment region comprising an LPETG motif, a hydrophobic transmembrane sequence, and a positively charged C terminus (9). Experiments carried out in vitro have shown that Bap promotes early adherence, as well as intercellular adhesion, of S. aureus cells (9). So far, Bap has been found only in isolates from mammary glands in ruminant suffering from mastitis. Experimental mammary gland infection studies indicated that Bap might act as an anti-attachment factor that prevents initial bacterial attachment to host tissues (10), although the presence of Bap facilitated the persistence of S. aureus in the mammary gland (49).

Ca2+ has been implicated in a large number of biological processes, in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells (reviewed in references 3, 28, and 31). This cation is a well-known intracellular second messenger that controls many vital processes (3), and there is increasing evidence that it is an extracellular first messenger in complex organisms (4, 25). In bacteria, Ca2+ is implicated in processes as important and diverse as the cell cycle and cell division, competence, pathogenesis, motility and chemotaxis, and quorum sensing (reviewed in references 19, 28, 30, 31, and 42). In the extracellular space, Ca2+ also has an important structural role, maintaining the integrity of the outer lipopolysaccharide layer and the cell wall (42). The EF-hand motif, initially observed in the X-ray structure of parvalbumin (22), remains one of the most widespread Ca2+-binding domains in nature, although various other Ca2+-binding domains have been identified (14, 36, 37, 48, 54). This motif comprises a 12-residue loop flanked on both sides by an α-helix, and residues at positions 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 12 of the loop provide the ligands that chelate the Ca2+ ion (22, 46). The majority of EF-hand proteins contain an even number of EF domains, and pairing of neighboring EF hands has been proposed to be important for the functionality of the domain (28, 52).

Several of the staphylococcal surface adhesins bind Ca2+. ClfA (clumping factor A) of S. aureus, which promotes binding to fibrinogen and fibrin, has a Ca2+-binding EF-hand-like motif in the fibrinogen-binding domain (33). The interaction of fibrinogen and ClfA is inhibited by addition of millimolar amounts of calcium (33). Similarly, clumping factor B (ClfB) of S. aureus has an EF-hand-like motif, and millimolar concentrations of Ca2+ and Mn2+ inhibit fibrinogen binding by ClfB (29). In contrast, the members of the serine-aspartate surface protein family (Sdr) bind Ca2+ with high affinity. Each of the B repeats of SdrD contains a canonical EF-hand motif and two acidic stretches with similarity to the putative Ca2+-binding sites of integrin. It has been shown that Ca2+ binding is required for the structural integrity of the B-repeat region in SdrD (21).

Analysis of the primary structure of Bap revealed the presence of sites with high levels of similarity to the EF-hand calcium-binding motif, indicating that Bap might be able to bind Ca2+. The important regulatory role of this metal cation in cellular processes and in protein function (28), as well as its high concentration in milk (51), led us to investigate its possible involvement in Bap function. In this report we show that calcium at concentrations equivalent to those found in milk inhibits Bap-mediated multicellular behavior of S. aureus in vitro. Furthermore, this inhibition is abolished by mutations at the putative EF-hand motifs, suggesting that Ca2+ binding at these EF-hand-like sites in wild-type Bap is indeed responsible for the effect of the cation on biofilm formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

S. aureus V329 is a strong biofilm-forming isolate obtained from bovine subclinical mastitis (9). S. aureus strain M556, which has a biofilm-negative phenotype, is an isogenic mutant of V329 whose bap gene has been disrupted by transposon insertion (9). S. aureus strain V858 is a Bap-positive bovine mastitis isolate, whose bap gene contains a single C repeat (11). S. aureus strain CH142 is a SaPIbov2 Bap-negative strain obtained in the laboratory from an originally SaPIbov2 Bap-positive strain. Strain JP38 is a V329 derivative in which the ica locus has been deleted (11). S. aureus strains 15981 and 12313, isolated in the Microbiology Department at the Clinic of the University of Navarra, were selected because of their strong biofilm production phenotype (50).

Culture conditions.

Staphylococcal strains were cultured in Trypticase soy agar and in Trypticase soy broth (TSB) supplemented with glucose (0.25%, wt/vol) (TSB-glucose) as indicated below. In addition, media were supplemented with calcium chloride (CaCl2), magnesium chloride (MgCl2), manganese chloride (MnCl2), EDTA, or EGTA at various concentrations when they were required by the experimental design. Escherichia coli XL1-Blue cells were grown in Luria-Bertani broth or on Luria-Bertani agar (Pronadisa, Madrid, Spain) with appropriate antibiotics. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: erythromycin, 1.5 μg ml−1; and ampicillin, 100 μg ml−1. The initial concentration of calcium in TSB was measured with the Arsenazo III commercial preparation (Sigma) used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

DNA manipulations.

DNA plasmids were isolated from E. coli strains with a Bio-Rad plasmid miniprep kit used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmids were transformed into staphylococci by electroporation by using a previously described protocol (9). Chromosomal DNA preparations were obtained as previously described (27). Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs. Oligonucleotides were obtained from Life Technologies (Invitrogen). DNA sequencing was performed with an ABI 310 model automatic sequencer (PE Biosystems) used according to manufacturer's protocols.

Construction of S. aureus strain Newman_Bap.

A single-copy integrating plasmid, pCL84 (23), was used to introduce the bap gene into S. aureus strain Newman (= ATCC 25905). pCL84 carries the att site of phage L54a but lacks a replicon that functions in S. aureus. When transformed into S. aureus CYL316 (23), which overexpresses the L54a integrase, the plasmid integrated into the chromosomal att site located in the geh gene. The bap gene of the S. aureus V858 strain, including its own native promoter, was amplified with Pfu DNA polymerase (Promega) by using primers Bap-1mB (5′-CGCGGATCCCTCTTCAGATCTACGAATTTTCCC-3′) and Bap-5cE (5′-CGGGAATTCACTTATAGATGTGCGTAGTC-3′) and was cloned in pCL84, generating pJP17. Plasmid pJP17 was transformed into CYL316 and integrated into the chromosome by homologous recombination at the phage L54a att site. The bap gene was then transduced by phage 85 (32) into strain S. aureus Newman, which produced strain Newman_Bap. Correct integration of pJP17 in CYL316 and Newman_Bap was verified by PCR and Southern blotting with lipase- and bap-specific probes.

Site-directed mutagenesis and allelic exchange of the chromosomal bap gene.

To introduce point mutations at the selected EF-like domains of Bap, synthetic oligonucleotides were designed to incorporate the desired modifications. These mutagenic primers were used in conjunction with the appropriate flanking sequence primers to amplify two fragments of DNA. A 500-bp segment of bap encompassing the EF2 domain was amplified by PCR from the V329 chromosomal DNA with the following primers: forward primer efa (5′-AACGGTATTTTCTCATATAGT-3′) (578) and reverse primer efb (5′-CACTTAAGGATAATTGACGATTATATCTATCTAATAAACCATCTTTAGCATAATTTTGTAGCGCTAG-3′) (746). Similarly, a 500-bp segment encompassing the EF3 domain was amplified with the following primers: forward primer efc (5′-TCCTTAAGTGATGCAGAAAACGAAAATACTGCTGGCGATGGTAAGAATGATGGCGATAATGTTGTAAATTAT-3′) (744) and reverse primer efd (5′-TTAATTGCTGCACTTGTATC-3′) (911). The numbers in parentheses correspond to the positions of the last amino acid encoded by the PCR fragment in the Bap protein according to the nomenclature of Cucarella et al. (9). The sequences of primers efb and efc differed from the original bap sequence at seven nucleotides (indicated by boldface type); three of the substitutions were silent mutations designed to generate a novel restriction site for AflII (indicated by underlining), and the remaining four substitutions resulted in the desired amino acid mutations in the EF2 (primer efb) and EF3 (primer efc) domains (see Fig. 5). The PCR products were cloned in the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), which resulted in pGEMT-D1 and pGEMT-F1, respectively. These constructs were sequenced on both strands to confirm that they contained the expected nucleotide changes. pGEMT-D1 and pGEMT-F1 were digested with EcoRI and AflII, and the two 500-bp EcoRI-AflII fragments containing bap sequences were ligated simultaneously into the EcoRI site of the shuttle plasmid pMAD (M. Arnaud and M. Debarbouille, unpublished) and transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue competent cells. The resulting construct, designated pMAD-D1F1, contained a 1,000-bp insert that included the region containing EF2 and EF3 and spanned approximately 500 bp upstream and downstream from this region. pMAD-D1F1 was introduced into S. aureus V329 by electroporation, and the transformed cells were selected on erythromycin plates. Since pMAD contains a temperature-sensitive origin of replication, chromosomal integration of the construct was promoted by growth at the nonpermissive temperature (43.5°C). Bacteria in which the integration had occurred via a two-step gene replacement event, which therefore contained no pMAD plasmid sequences, were selected as previously described (50), and clone V329_EF23 was chosen for further analysis. Replacement of the chromosomal bap sequence was confirmed by PCR amplification performed with oligonucleotides efa and efd and digestion with AflII. Following replacement, the sequence of the fragment was determined. To do this, a PCR fragment amplified with oligonucleotides 6m (5′-CCCTATATCGAAGGTGTAGAATTGCAC-3′) (602) and 7c (5′-GCTGTTGAAGTTAATACTGTACCTGC-3′) (926) was cloned in pGEMT and sequenced (see above for explanation of numbers in parentheses).

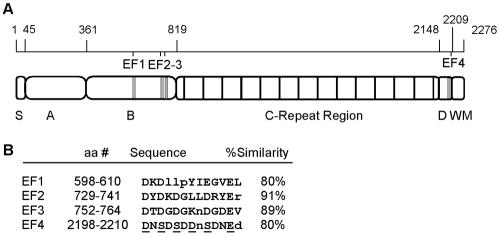

FIG. 5.

Mutation of the potential EF-hand motifs EF2 and EF3. (A) Amino acid substitutions introduced into the chromosomal copy of bap in V329 to configure mutant V329_EF23. The positions at which residues were replaced are underlined, and the arrows indicate the residues introduced into the mutant. (B) Formation of biofilms on microplates by V329 and mutant V329_EF23 grown overnight in TSB-glucose supplemented with different amounts of Ca2+. (C) Liquid culture tubes containing V329_EF23 grown overnight in TSB-glucose or TSB-glucose supplemented with 10 mM Ca2+. The degree of bacterial clumping of the mutant was not affected by Ca2+ addition. The results of a representative experiment are shown.

Biofilm formation assays.

Biofilm formation assays on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plates were performed as described previously (18). Briefly, 5 μl of a culture of S. aureus grown overnight in TSB-glucose at 37°C was inoculated into the wells of microtiter plates containing 195 μl of TSB-glucose (final dilution of the culture, 1:40). Sterile 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates from the same manufacturer (Iwaki) were used throughout the study. When required, 5 μl of a divalent cation or chelating agent solution was added to the wells to obtain the appropriate final concentration. This addition was done at the time of inoculation of the plate. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, the microplates were washed twice with 200 μl of H2O, dried in an inverted position, and stained with 100 μl of 0.25% crystal violet for 20 min at room temperature. Microplates were rinsed again twice with H2O, dried, and photographed. At least three independent cultures were assayed for each experiment, and four replicates were used for each culture.

Intercellular adhesion in liquid media.

Culture tubes containing 5 ml of TSB-glucose supplemented with the appropriate concentrations of CaCl2 or EDTA were inoculated with a fresh colony of S. aureus strain V329 or M556 and incubated for 16 to 24 h at 37°C in a platform shaker (New Brunswick) at 200 rpm. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of an aliquot taken from the bulk of the culture was determined before and after vigorous vortexing of the tube; the aliquots were diluted as required to obtain OD600 values that were less than 0.3. The measured optical density values were corrected for the dilution factor and volume proportion. The percentage of suspended cells in each tube was calculated from the ratio of the corrected OD600 values obtained for the culture before and after vortexing. The experiments were repeated at least three times.

Early adherence assay.

Early adherence to a polystyrene surface was determined as previously described (9), with the following modifications. Overnight cultures of S. aureus strains were grown in TSB supplemented with 0.25% glucose at 37°C and diluted 1:100 in fresh media. After 3 h, the bacterial cultures were diluted to obtain an OD600 of 0.1. Ten milliliters of each suspension was added to two polystyrene petri dishes and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The petri dishes were washed at least five times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were fixed with Bouin solution and Gram stained. Adherent bacterial cells were observed by oil immersion microscopy and counted; the results given below represent the means of four different microscopic fields. Each experiment was repeated three times.

Surface-associated protein preparation.

Surface protein preparations were obtained from S. aureus cells under isosmotic conditions. Bacterial cells were recovered from 5-ml overnight cultures by centrifugation, washed twice in 1 ml of PBS, and resuspended in 100 μl of isosmotic digestion buffer (PBS containing 26% [wt/vol] raffinose). After addition of 3 μl of a 10-mg/ml solution of lysostaphin (Sigma), the preparations were incubated with shaking at 37°C for 2 h. Protoplasts were sedimented by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 30 min with slow deceleration, and the supernatant was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) or stored at −80°C.

Electrophoresis and Western blot analysis.

Electrophoretic separation of cell wall-associated protein preparations was carried out by SDS-PAGE. The acrylamide concentration was 7.5% in the resolving gel and 4% in the stacking gel. For Western blot analysis, protein extracts separated by SDS-PAGE were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) at 0.8 mA/cm2 for 5 h in a semidry transfer apparatus (Pharmacia). The buffer used for transfer was 50 mM Tris (pH 8.3)-380 mM glycine-0.1% SDS-20% methanol. The blocking solution contained PBS, 5% milk powder, and 6% Tween 20. Serum containing anti-Bap antibody (9) was adsorbed against inactivated M556 cells and then used as the primary antibody at a 1:5,000 dilution. Peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Pierce) diluted 1:10,000 was used as the secondary antibody, and the reaction was developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL kit; Roche). An image was obtained with a Chemi-Doc apparatus (Bio-Rad).

Sequence analysis program.

The predicted amino acid sequence of Bap was analyzed with the PrositeScan program (6) at the web server http://npsa-pbil.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page = npsa_prosite.html in order to identify potential functional domains.

RESULTS

Potential metal ion-binding motifs in the Bap sequence.

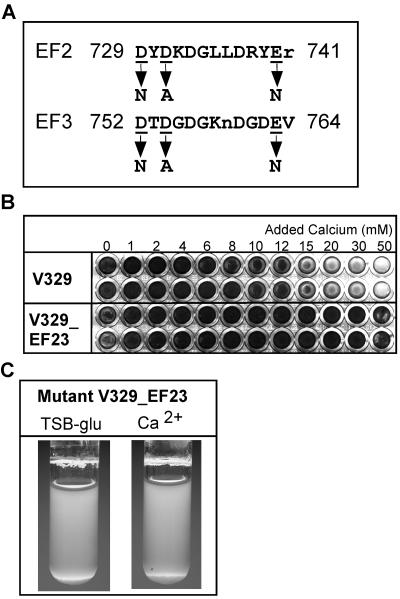

A motif search of the amino acid sequence of Bap by using the Prosite PS00018 definition revealed the presence of four sites with ≥80% similarity to the loop of the consensus EF-hand motif. Figure 1 shows the relative positions of these potential calcium-binding sites, designated EF1 to EF4 from the N terminus to the C terminus. Three of the sites are located N terminal to the C-repeat region of Bap, whereas the fourth is located at the C terminus close to the cell wall-anchoring LPETG motif, within the SD-rich sequence. The second and third of these potential EF-hand motifs, designated EF2 and EF3, exhibit the greatest similarity to the consensus sequence, differing from it at a single position. The proximity of EF2 and EF3 suggests that they might act coordinately as a pair of EF-hand domains (28).

FIG. 1.

EF-hand-like domains in the Bap sequence. (A) Positions of the potential EF hands, shown in a diagram representing the structural organization of Bap. S, signal peptide; A, region A; B, region B; C, C-repeat region; D, region rich in serine-aspartate (SD) repeats; WM, cell wall anchor, membrane-spanning region, and positively charged tail. The positions of the potential EF-hand-like motifs, designated EF1 to EF4, are indicated by vertical grey lines. (B) Sequences of the four potential EF-hand motifs in Bap and degrees of similarity to the consensus sequence. Residues that do not conform to the EF-hand loop consensus sequence are in lowercase letters. The positions that participate in coordinating Ca2+ are underlined. aa, amino acid.

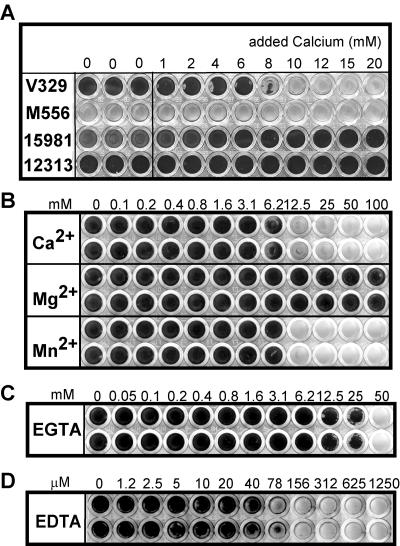

Effects of divalent cations on Bap-mediated biofilm formation.

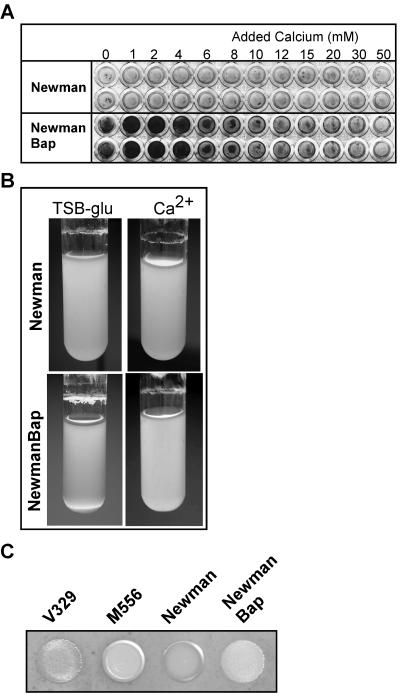

To determine if calcium had any functional significance in Bap-mediated biofilm formation, we assayed V329 biofilm-forming ability in the presence of increasing Ca2+ concentrations. Figure 2A shows that biofilm formation on polystyrene microplates by S. aureus V329 was inhibited by addition of 6 to 10 mM calcium to the growth medium. The Bap-deficient isogenic mutant M556 did not form a biofilm under any of the conditions tested. S. aureus strains 15981 and 12313 are clinical isolates which do not contain the bap gene in the genome, and therefore biofilm formation by these strains is not Bap dependent. We observed that for 15981 and 12313 addition of up to 20 mM Ca2+ did not have an inhibitory effect on biofilm formation. In fact, Ca2+ even enhanced the amount of biofilm formed by strain 15981. In addition, we observed that the inhibitory effect did not occur with all divalent cations. Addition of Mg2+ did not affect the biofilm formed by Bap-positive strain V329, whereas Mn2+ had an inhibitory effect at the same concentration range as Ca2+ (Fig. 2B), although there was a sharper transition from the permissive to inhibitory concentrations of the cation. It should be noted that the actual Ca2+ concentration required for biofilm inhibition ranged from 6 to 15 mM in different experiments. This variation was determined to depend on the microplate used, despite the fact that microplates from a single manufacturer were used throughout the study.

FIG. 2.

Effects of divalent cations and chelating agents on V329 biofilm formation. Bacteria were inoculated onto microtiter plates containing TSB-glucose supplemented with Ca2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, EGTA, or EDTA at the final concentrations indicated. After 24 h of incubation the microplates were washed and stained with crystal violet. (A) Effect of Ca2+ addition on the ability of S. aureus strains V329, M556, 15981, and 12313 to form biofilms. (B) Effect of Ca2+, Mg2+, and Mn2+ on the ability of V329 to form a biofilm. (C) Effect of EGTA addition on the biofilm formed by V329 in TSB-glucose. (D) Effect of EDTA addition on the biofilm formed by V329 in TSB-glucose. The results of a representative experiment are shown.

PIA/PNAG has been implicated in biofilm formation by S. aureus (8, 26). Although Ca2+ did not affect PIA/PNAG-mediated biofilm formation by strain 15981 (50), to confirm that calcium inhibition was independent of the presence of PIA/PNAG, biofilm formation experiments were performed with strain JP38 (V329Δica) (11). With this strain we observed the same calcium-mediated biofilm inhibition that we observed with V329, indicating that in V329 PIA/PNAG is not necessary for the observed calcium inhibition (data not shown).

Bap promoted both primary attachment and intercellular aggregation (9). To determine whether calcium affects primary attachment, early adherence of S. aureus V329 in the presence or absence of calcium was measured by phase-contrast microscopy. The results showed that S. aureus V329 adhered to polystyrene more efficiently in the absence of calcium (2.8 × 103 cells/field) than in the presence of 10 mM calcium (1.0 × 103 cells/field).

Effect of Ca2+ depletion on biofilm formation.

We found that addition of up to 25 mM EGTA had little effect on the V329 biofilm obtained after 24 h of incubation (Fig. 2C). These conditions likely represent Ca2+ depletion since the concentration of total calcium present in the nonsupplemented medium was less than 1 mM, as determined by the Arsenazo III method. In contrast to the results obtained for EGTA, EDTA inhibited V329 biofilm formation at concentrations as low as 80 μM (Fig. 2D). Given the different affinities of these chelators for the various metal ions (13), these results indicate that it is unlikely that Ca2+ is necessary for biofilm formation by V329 but that there is another metal ion which is preferentially chelated by EDTA and which is essential for this process.

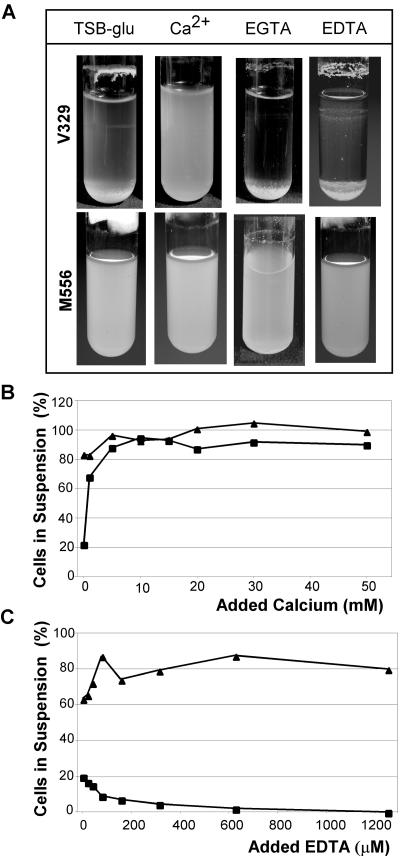

Effect of Ca2+ on Bap-mediated bacterial clumping.

Overnight shaken cultures of V329 grown in tubes of TSB-glucose showed very little turbidity; the majority of the cells precipitated and were at the bottom of the tube or were present in a growth ring at the air-liquid interface (Fig. 3A). Bap is essential for the observed aggregative behavior of V329, because cultures of the isogenic Bap-deficient strain M556 exhibited much greater turbidity and did not form an interfacial ring (Fig. 3A). We observed that addition of Ca2+ at millimolar levels to the liquid culture tubes practically abolished bacterial aggregation in V329 liquid cultures (Fig. 3A and B). In the presence of 10 mM added Ca2+, the behavior of V329 was practically indistinguishable from that of M556; that is, at this Ca2+ concentration the Bap-positive strain exhibited a Bap-negative phenotype. Addition of 1.25 mM EGTA had the opposite effect, reinforcing the intercellular aggregation and rendering the liquid bulk practically free of suspended cells (Fig. 3A). Similarly, addition of EDTA promoted bacterial intercellular adhesion, but this agent also caused a decrease in the total bacterial density (the number of bacteria in the EDTA-supplemented culture was 1010 CFU, compared with 1011 CFU in the TSB culture), which was not observed with EGTA (Fig. 3A and C). In contrast, the turbidity of M556 liquid cultures was essentially unaffected by addition of either Ca2+ or chelating agents.

FIG. 3.

Ca2+ inhibits V329 bacterial clumping in liquid culture tubes. (A) Culture tubes containing TSB-glucose were inoculated with V329 or M556, and Ca2+, EGTA, and EDTA were added as indicated to final concentrations of 10, 1.25, and 1.25 mM, respectively. After 16 h of incubation at 37°C, the tubes were photographed. (B) Percentages of suspended cells in V329 and M556 liquid cultures grown in TSB-glucose supplemented with different amounts of Ca2+. The results of a representative experiment are shown. (C) Same as panel B, except that EDTA was added to the culture tubes. Symbols: ▪, V329; ▴, M556.

Figures 3B and C show the degrees of bacterial clumping present in V329 and M556 liquid cultures grown overnight in the presence of increasing calcium or EDTA concentrations. The percentage of suspended bacteria in V329 cultures increased almost threefold for concentrations of added calcium between 0 and 15 mM. Further increases in the Ca2+ concentration had no detectable effect on V329 bacterial aggregation. The same amount of added Ca2+ did not significantly increase the proportion of suspended cells in M556 cultures. The actual percentage of suspended cells increased with culture age (between 16 and 24 h.), but in any case the difference between the Bap-positive and Bap-negative strains disappeared when calcium was added at millimolar levels to the culture of the Bap-positive strain. Addition of EDTA promoted bacterial aggregation in V329 cultures, reducing to practically zero the proportion of suspended cells at the highest concentrations assayed. In contrast, EDTA did not promote clumping of M556 cultures (Fig. 3C).

Bap expression in the Newman strain elicits the formation of a calcium-dependent biofilm.

To determine that the observed inhibitory effect of calcium on Bap-mediated biofilm formation did not occur exclusively in strain V329, we expressed Bap in a different genetic background. The S. aureus Newman strain does not form biofilms (Fig. 4A). We produced a recombinant derivative of this strain, designated Newman_Bap, in which the bap gene was inserted into the bacterial chromosome. We observed that insertion of the bap gene into the Newman chromosome rendered the bacteria competent for biofilm formation on microplates (Fig. 4A) and for cell-to-cell aggregation when the organism was grown in tubes (Fig. 4B). These multicellular behavior properties elicited by Bap in the mutant were inhibited by added calcium at concentrations similar to those used for V329 (Fig. 4A and B). Thus, the biofilm-positive phenotype and the calcium inhibition phenotype were simultaneously transferred to the Newman strain by insertion of the bap gene. These results strongly suggest that Bap is the cell component unique to V329 necessary to elicit formation of a calcium-dependent biofilm in the Newman strain. In addition, the transfer of Bap to the Newman strain conferred aggregative colony morphology to the Newman_Bap strain (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Expression of Bap changes the multicellular behavior of the Newman strain. (A) Biofilm formation by strains Newman and Newman_Bap on microtiter plates containing TSB-glucose supplemented with different amounts of Ca2+. Newman cells did not form a biofilm after 24 h of incubation, whereas the Newman_Bap mutant that contained a chromosomal copy of bap formed a biofilm and this biofilm was inhibited by millimolar amounts of added Ca2+. (B) Liquid culture tubes containing Newman and Newman_Bap grown overnight in TSB-glucose or TSB-glucose supplemented with 10 mM Ca2+. Liquid cultures of Newman_Bap exhibited a greater degree of bacterial clumping than Newman cultures, and the clumping was inhibited by addition of 10 mM Ca2+ to the growth medium. The results of a representative experiment are shown. (C) Colony morphology on Congo red agar plates incubated at 37°C for 24 h for strains V329, M556, Newman, and Newman_Bap.

Mutation of EF2 and EF3 eliminates Ca2+ inhibition in a Bap-mediated biofilm.

To obtain evidence of whether the identified EF-like domains mediated the calcium-Bap interaction, we mutated EF2 and EF3 in the chromosomal copy of the V329 bap gene. EF2 and EF3 were chosen from all of the potential Ca2+-binding sites in Bap because of their better features for being functional EF-hand domains (28). As shown in Fig. 5A, acidic amino acid residues of EF2 and EF3 corresponding to positions 1, 3, and 12 of the consensus EF-hand loop were replaced by Asn, Ala, and Asn, respectively. Thus, we obtained a Bap mutant that contained the following amino acid substitutions: D729N, D731A, E740N, D752N, D754A, and E763N. These three positions are the most conserved positions in the EF-hand motif, and when the sequences were scanned with the PrositeScan program, no potential EF hands were found in the substituted sequence. These mutations were introduced into V329 by allelic exchange, producing the mutant strain V329_EF23, which was expected to express a Bap version with reduced Ca2+-binding capabilities. Figures 5B and C show that the behavior of V329_EF23 was very similar to that of V329 when it was grown in TSB-glucose in microplates and tubes. However, when the organism was grown in the presence of a Ca2+ concentration inhibitory to the parental V329 strain, the multicellular behavior of V329_EF23 was not affected. The mutant strain formed biofilms in microplates at concentrations of added Ca2+ up to 50 mM and formed bacterial clumps in liquid culture tubes in the presence of 10 mM added Ca2+ (Fig. 5B and C). In addition, primary attachment of the V329_EF23 mutant was not affected by addition of calcium (data not shown). As shown below, these mutations did not affect Bap protein expression (Fig. 6).

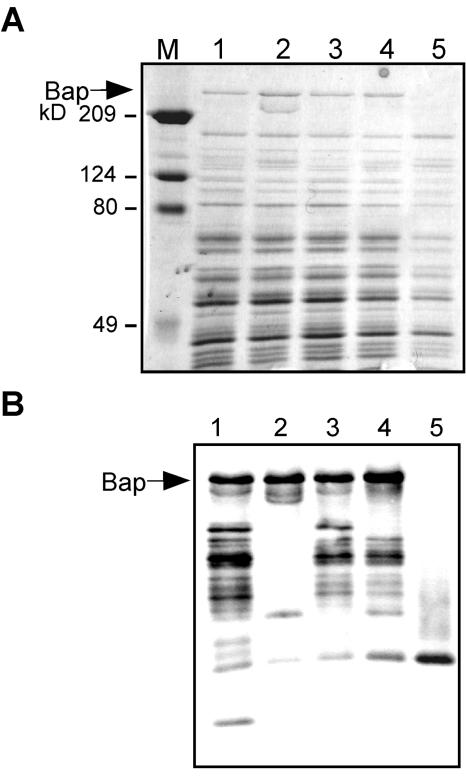

FIG. 6.

Analysis of surface protein preparations. (A) SDS-PAGE of surface protein preparations obtained under isosmotic conditions. Lane M, Bio-Rad prestained broad-range Mr standards; lane 1, V329 grown in TSB-glucose; lane 2, V329 grown in TSB-glucose supplemented with 10 mM Ca2+; lane 3, mutant V329_EF23 grown in TSB-glucose; lane 4, mutant V329_EF23 grown in TSB-glucose supplemented with 10 mM Ca2+; lane 5, negative control preparation obtained from Bap-negative S. aureus strain CH142 grown in TSB-glucose. (B) Western blot analysis with anti-Bap serum. For lane contents see above. The amounts of each preparation loaded for SDS-PAGE and Western analysis were 10 and 0.2 μl, respectively. The arrow indicates the position of full-size Bap.

Bap is expressed by bacteria grown in TSB containing Ca2+.

In the presence of added Ca2+, the Bap-positive strain V329 exhibited a biofilm-negative phenotype similar to that of the Bap-negative strain M556. Thus, under these conditions, either Bap was not expressed by V329 or Bap was expressed but was present as a nonfunctional form. To investigate this, surface protein preparations obtained from bacteria grown in the presence and in the absence of added Ca2+ were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. Figure 6A shows the results of SDS-PAGE of surface protein preparations obtained from V329 and from mutant V329_EF23. No decrease was observed in the amount of Bap extracted from strain V329 grown at calcium concentrations that caused inhibition of intercellular adhesion. Thus, Ca2+ inhibition of Bap-mediated bacterial multicellular behavior is not due to repression of Bap expression.

In the Western blot analysis, protein preparations obtained from V329 grown in TSB-glucose produced a considerable number of bands that reacted with the anti-Bap serum (Fig. 6B, lane 1). This is not surprising if we consider that the preparations were obtained in the absence of protease inhibitors. However, with the protein preparations obtained from V329 grown in TSB supplemented with 10 mM Ca2+ there was a remarkable decrease in the number of reactive bands (Fig. 6B, compare lanes 1 and 2). Protein preparations obtained from mutant V329_EF23 grown in TSB exhibited a degradation pattern quite similar to that of V329 (Fig. 6B, compare lanes 1 and 3). However, the band pattern obtained for V329_EF23 grown in Ca2+-supplemented TSB closely resembled that of V329_EF23 grown in the absence of added Ca2+ (Fig. 6B, compare lanes 3 and 4). Thus, protection from proteolysis was much less prominent for this mutant than for wild-type Bap when bacteria were grown in the presence of a high Ca2+ concentration (Fig. 6B, compare lanes 2 and 4). These Western blot results suggest that Ca2+ binding triggers a conformational change in Bap such that the metal-bound protein becomes more resistant to degradation. Consistently, the Bap mutant expressed by V329_EF23 was protected to a lesser extent by high Ca2+ concentrations, as would be expected for a protein with reduced capabilities for Ca2+ binding and therefore for undergoing a Ca2+-induced conformational change.

DISCUSSION

In this study we used biofilm formation on polystyrene microplates and cell clumping in liquid cultures as assays for the multicellular behavior of staphylococcal cells. We found that addition of millimolar amounts of Ca2+ to the growth medium of Bap-positive strain V329 inhibits biofilm formation, as well as bacterial clumping in liquid culture. Indeed, at these high concentrations, Ca2+ cancels the action of Bap and results in V329 behaving in the same way that the Bap-deficient mutant M556 behaves. Similarly, in the presence of millimolar amounts of added Ca2+ the biofilm-positive Newman_Bap mutant exhibits the biofilm-negative phenotype of the wild-type Newman strain. Taken together, these results are a strong indication that Ca2+ inhibition is an intrinsic property of Bap-mediated biofilms. The inhibition is not due to nonspecific electrostatic interference with the plastic-bacterium interactions, since it is not observed for all divalent cations and it also takes place in liquid cultures in which surface interactions are less relevant. The lack of an effect of Ca2+ on S. aureus strains 15981 and 12313 indicates that Ca2+ modulation does not occur with all PIA/PNAG-dependent staphylococcal biofilms. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that the biofilms of other Bap-negative staphylococcal strains might be modulated by Ca2+, since multiple, diverse mechanisms are used for biofilm formation under different environmental conditions or by different bacterial strains (12, 34, 50). To our knowledge, this is the first report of Ca2+ acting as a biofilm regulator through interaction with a surface protein. Recently, Cah has been characterized as a Ca2+-binding surface protein implicated in biofilm formation by enterohemorrhagic E. coli serotype O157:H7 (48). It has been shown that Cah is expressed under conditions of Ca2+ depletion. It would be interesting to know if, as in the case of Bap, Ca2+ binding affects the function of Cah in biofilm formation.

According to our results, Bap mediates intercellular adhesion through a calcium-dependent mechanism. Expression of Bap on the surface of the biofilm-negative Newman strain is sufficient to promote bacterial aggregation and to confer a biofilm-positive phenotype to this strain. This supports the idea that in connecting cells Bap might interact with itself through homophilic interactions, thus acting as both a receptor and a ligand, similar to the behavior of cadherins (41). This is consistent with the failure to find a specific ligand for Bap (10). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that Bap acts as a C-type (Ca2+-dependent) lectin and binds, in a Ca2+-dependent manner, sugar moieties in the exopolysaccharide of neighboring cell walls. This type of mechanism involving binding of surface lectins to cell wall carbohydrates of other cells has been described to mediate yeast flocculation (44, 45). One difference is that for cadherins as well as for C-type lectins, Ca2+ acts as positive regulator of cell adhesion, whereas for Bap, Ca2+ acts as an inhibitor.

There are several cell wall components of gram-positive bacteria, like proteins, exopolysaccharides, or lipoteichoic acid, that bind Ca2+ (21, 33, 38-40, 47). In addition, Bap contains multiple potential Ca2+-binding sites. The C-terminal repeats likely belong to the HYR family of domains, whose members are suspected to interact with Ca2+ (5, 53). In addition, the four sites with greater than 80% similarity to the EF-hand loop increased to 14 potential EF-hand domains when the similarity constraint was lowered to 70%. Thus, it was not clear if Ca2+ interacted directly with Bap and, if that was the case, if it bound at the EF-hand motifs identified. The C-terminal repeats are likely not essential for calcium inhibition of biofilm formation since the biofilm of the Newman_Bap mutant, expressing a Bap copy with a single C repeat, exhibits a sensitivity to the metal similar to that of the biofilm of V329, whose Bap copy contains 13 C repeats. Site-directed mutagenesis of the EF2 and EF3 domains was consistent with the hypothesis that Ca2+ binding at these sites is essential for the inhibition of biofilm formation. The V329_EF23 mutant formed biofilm like the wild-type V329 strain, but Ca2+ inhibition was virtually abolished by the mutations designed to eliminate Ca2+ binding at EF2 and EF3. This result brings into question the possible contribution of the remaining Ca2+-binding domains to the Ca2+-exerted inhibition. However, we do not know the relative contributions of EF2 and EF3 to this process. Biofilm formation was not impaired by the mutations, indicating that the mutant protein is functional and participates in the interactions that drive biofilm formation. Furthermore, the inhibition by Mn2+ and EDTA of the V329_EF23 biofilm was identical to the inhibition of the wild-type V329 strain biofilm (data not shown). Thus, these point mutations did not alter the overall structure of Bap.

The calcium-binding sites in Bap do not conform strictly to the consensus sequence, and they do not present predicted flanking α-helices. Similarly, the EF-hand-like domains found in ClfA and ClfB do not correspond to the prototype of the EF-hand motif but constitute functional Ca2+-binding domains (29, 33). With a certain parallelism to what we observed with Bap, millimolar amounts of Ca2+ and Mn2+ (but not Mg2+) inhibit the interaction of fibrinogen and ClfA (33) or ClfB (29). The positions of the putative Ca2+-binding motifs in these three proteins are similar (the N-terminal domain of the protein outside the repeat region). In contrast, the Ca2+-binding motifs of SdrD are located in the B-repeat region, conform to the prototype EF-hand domain, and bind the metal with high affinity, with a Kd in the micromolar range (21). However, no ligand or function has been assigned to these proteins, so the effect of Ca2+ binding on the function of SdrD remains unknown.

Our results demonstrate that the Ca2+ inhibition of the Bap-mediated bacterial multicellular behavior is not due to repression of Bap expression. Instead, our results are consistent with the hypothesis that calcium causes a conformational change in Bap that affects its ability to form biofilms. Many calcium-binding proteins, including ClfA (33), ClfB, and the B-repeats of SdrD (21) among others, undergo considerable conformational changes upon binding of the metal cation. In general, the metal-bound form is structurally more organized than the metal-free form and, consequently, more resistant to proteolytic enzymes (21). Consistently, we have observed that Bap in protein preparations obtained from V329 grown in the presence of a high Ca2+ concentration exhibits a lower degree of proteolytic degradation than Bap in protein preparations from V329 grown in TSB-glucose. In addition, protection from proteolysis in the presence of Ca2+ is much less prominent in protein preparations from mutant V329_EF23, which expresses a version of Bap with reduced Ca2+-binding ability. This result supports the hypothesis that the protective effect of Ca2+ on the protein preparations obtained from V329 is exerted at least partially through a conformational transition in Bap instead of other possibilities, like inhibition of an extracellular protease.

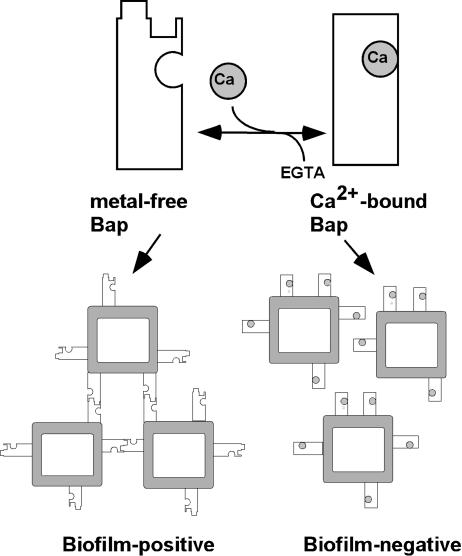

Based on our results, we propose the model shown in Fig. 7 for the effect of Ca2+ on Bap-mediated biofilm formation. According to our results, Bap presents a low-affinity inhibitory cation-binding site. Thus, when V329 grows in TSB-glucose, the Ca2+ concentration should be in the submillimolar range, and the EF hands of Bap should not be saturated with Ca2+. The metal-free form of Bap should be compatible with intercellular aggregation and biofilm formation. When V329 grows in TSB-glucose supplemented with millimolar amounts of Ca2+, Bap should be in the Ca2+-saturated form. Binding of the ion should trigger a conformational transition in Bap such that the metal-bound protein becomes noncompetent for mediating intercellular aggregation and biofilm formation.

FIG. 7.

Model illustrating the effect of Ca2+ on Bap conformation and biofilm formation. Metal-free Bap participates in the series of interactions that lead to cell-to-cell adhesion and biofilm formation. Occupation of the inhibitory site(s) by Ca2+ induces a conformational change in Bap and renders the protein noncompetent for biofilm formation. The ligand for Bap on neighboring cells is illustrated as other Bap molecules, but it could be a different type of molecule. Only at high Ca2+ concentrations would Bap be saturated with the metal, whereas chelating agents would favor the metal-free form.

For Ca2+ to serve as a regulator of Bap function, the binding affinity of the protein for the cation should be such that the changes in the local Ca2+ concentration result in large differences in the degree of saturation of Ca2+-binding sites in the protein. In milk, the Ca2+ concentration is around 32 mM, and only one-third of the total cations are found in the serum (51). Thus, we estimated that the concentration of free Ca2+ in serum was ∼11 mM. The concentration of free Ca2+ in mammalian blood is stringently maintained between 1.1 and 1.3 mM (4, 24, 25). Thus, fluctuations in the calcium concentration are probably great in the mammary gland environment (for example, between lactation and dry periods). In addition, sites where there are low local Ca2+ concentrations likely occur in an inflamed mammary gland as a result of increased permeability of blood vessels and concomitant altered ionic chemical balances (1, 2). Mammary gland inflammation takes place not only in advanced mastitis infections but also in stress situations or during physiological changes (start of the dry period and around parturition). The observed calcium-dependent bacterial behavior might have important implications for the propagation of bacteria. Initial rapid planktonic growth and horizontal spread may take place during lactation, and subsequent formation of a biofilm consisting of resistant multicellular communities in the mammary gland may result in chronic infections which persist in the animal, making it a bacterial reservoir. There are not many other situations or niches in which the Ca2+ concentration reaches the high values that inhibit the function of Bap; there are only a few exceptions, like the intracellular Ca2+ stores of eukaryotic cells, the sites of bone resorption, and seawater (4, 25, 28). Thus, the Bap-mediated biofilm seems to be a system specialized for the conditions present in the mammary gland, which is consistent with the fact that so far Bap has been found only in mastitis isolates (9).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología of Spain through grant BIO2002-01841 to M.J.A. and grant BIO2002-04542-C02 to I.L. and J.P. and by the Beca Ortiz de Landazuri award from the Departamento de Salud del Gobierno de Navarra. A.T.-A. is a predoctoral fellow of the Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte (FPU), Spain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alais, C. 1984. Science du lait: principes des techniques laitières, 4th ed. SEPAIC, Paris, France.

- 2.Blood, D. C., J. H. Arundel, C. C. Gay, J. A. Henderson, and O. M. Radostits. 1979. Veterinary medicine: a textbook of the diseases of cattle, sheep, pigs and horses. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 3.Bootman, M. D., and M. J. Berridge. 1995. The elemental principles of calcium signaling. Cell 83:675-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, E. M., P. M. Vassilev, and S. C. Hebert. 1995. Calcium ions as extracellular messengers. Cell 83:679-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callebaut, I., D. Gilges, I. Vigon, and J. P. Mornon. 2000. HYR, an extracellular module involved in cellular adhesion and related to the immunoglobulin-like fold. Protein Sci. 9:1382-1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Combet, C., C. Blanchet, C. Geourjon, and G. Deleage. 2000. NPS@: network protein sequence analysis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25:147-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costerton, J. W., Z. Lewandowski, D. E. Caldwell, D. R. Korber, and H. M. Lappin-Scott. 1995. Microbial biofilms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49:711-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cramton, S. E., C. Gerke, N. F. Schnell, W. W. Nichols, and F. Gotz. 1999. The intercellular adhesion (ica) locus is present in Staphylococcus aureus and is required for biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 67:5427-5433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cucarella, C., C. Solano, J. Valle, B. Amorena, I. Lasa, and J. R. Penades. 2001. Bap, a Staphylococcus aureus surface protein involved in biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 183:2888-2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cucarella, C., M. A. Tormo, E. Knecht, B. Amorena, I. Lasa, T. J. Foster, and J. R. Penades. 2002. Expression of the biofilm-associated protein interferes with host protein receptors of Staphylococcus aureus and alters the infective process. Infect. Immun. 70:3180-3186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cucarella, C., M. A. Tormo, C. Ubeda, M. P. Trotonda, M. Monzon, C. Peris, B. Amorena, I. Lasa, and J. R. Penades. 2004. Role of biofilm-associated protein Bap in the pathogenesis of bovine Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 72:2177-2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davey, M. E., and A. G. O'Toole. 2000. Microbial biofilms: from ecology to molecular genetics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:847-867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson, R. M. C., D. C. Elliott, W. H. Elliott, and K. M. Jones. 1986. Data for biochemical research, 3rd ed. Clarendon Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 14.Economou, A., W. D. Hamilton, A. W. Johnston, and J. A. Downie. 1990. The Rhizobium nodulation gene nodO encodes a Ca2+-binding protein that is exported without N-terminal cleavage and is homologous to haemolysin and related proteins. EMBO J. 9:349-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster, T. J., and M. Hook. 1998. Surface protein adhesins of Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol. 6:484-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghigo, J. M. 2003. Are there biofilm-specific physiological pathways beyond a reasonable doubt? Res. Microbiol. 154:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gotz, F. 2002. Staphylococcus and biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1367-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heilmann, C., O. Schweitzer, C. Gerke, N. Vanittanakom, D. Mack, and F. Gotz. 1996. Molecular basis of intercellular adhesion in the biofilm-forming Staphylococcus epidermidis. Mol. Microbiol. 20:1083-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holland, I. B., H. E. Jones, A. K. Campbell, and A. Jacq. 1999. An assessment of the role of intracellular free Ca2+ in E. coli. Biochimie 81:901-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Josefsson, E., K. W. McCrea, D. Ni Eidhin, D. O'Connell, J. Cox, M. Hook, and T. J. Foster. 1998. Three new members of the serine-aspartate repeat protein multigene family of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology 144:3387-3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Josefsson, E., D. O'Connell, T. J. Foster, I. Durussel, and J. A. Cox. 1998. The binding of calcium to the B-repeat segment of SdrD, a cell surface protein of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 273:31145-31152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kretsinger, R. H., and C. E. Nockolds. 1973. Carp muscle calcium-binding protein. II. Structure determination and general description. J. Biol. Chem. 248:3313-3326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, C., S. Buranen, and Z. Ye. 1991. Construction of single-copy integration vectors for Staphylococcus aureus. Gene 103:101-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maurer, P., and E. Hohenester. 1997. Structural and functional aspects of calcium binding in extracellular matrix proteins. Matrix Biol. 15:569-580. (Discussion, 15:581.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maurer, P., E. Hohenester, and J. Engel. 1996. Extracellular calcium-binding proteins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 8:609-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKenney, D., K. L. Pouliot, Y. Wang, V. Murthy, M. Ulrich, G. Doring, J. C. Lee, D. A. Goldmann, and G. B. Pier. 1999. Broadly protective vaccine for Staphylococcus aureus based on an in vivo-expressed antigen. Science 284:1523-1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mengaud, J., S. Dramsi, E. Gouin, J. Vazquez-Boland, G. Milon, and P. Cossart. 1991. Pleiotropic control of Listeria monocytogenes virulence factors by a gene that is autoregulated. Mol. Microbiol. 5:2273-2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michiels, J., C. Xi, J. Verhaert, and J. Vanderleyden. 2002. The functions of Ca2+ in bacteria: a role for EF-hand proteins? Trends Microbiol. 10:87-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ni Eidhin, D., S. Perkins, P. Francois, P. Vaudaux, M. Hook, and T. J. Foster. 1998. Clumping factor B (ClfB), a new surface-located fibrinogen-binding adhesin of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 30:245-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norris, V., M. Chen, M. Goldberg, J. Voskuil, G. McGurk, and I. B. Holland. 1991. Calcium in bacteria: a solution to which problem? Mol. Microbiol. 5:775-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norris, V., S. Grant, P. Freestone, J. Canvin, F. N. Sheikh, I. Toth, M. Trinei, K. Modha, and R. I. Norman. 1996. Calcium signalling in bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 178:3677-3682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Novick, R. P. 1991. Genetic systems in staphylococci. Methods Enzymol. 204:587-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Connell, D. P., T. Nanavaty, D. McDevitt, S. Gurusiddappa, M. Hook, and T. J. Foster. 1998. The fibrinogen-binding MSCRAMM (clumping factor) of Staphylococcus aureus has a Ca2+-dependent inhibitory site. J. Biol. Chem. 273:6821-6829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Toole, G., H. B. Kaplan, and R. Kolter. 2000. Biofilm formation as microbial development. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:49-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rich, R. L., B. Demeler, K. Ashby, C. C. Deivanayagam, J. W. Petrich, J. M. Patti, S. V. Narayana, and M. Hook. 1998. Domain structure of the Staphylococcus aureus collagen adhesin. Biochemistry 37:15423-15433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rigden, D. J., M. J. Jedrzejas, and M. Y. Galperin. 2003. An extracellular calcium-binding domain in bacteria with a distant relationship to EF-hands. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 221:103-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rizo, J., and T. C. Sudhof. 1998. C2-domains, structure and function of a universal Ca2+-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 273:15879-15882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rose, R. K. 2000. The role of calcium in oral streptococcal aggregation and the implications for biofilm formation and retention. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1475:76-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rose, R. K., and S. D. Hogg. 1995. Competitive binding of calcium and magnesium to streptococcal lipoteichoic acid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1245:94-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rose, R. K., S. D. Hogg, and R. P. Shellis. 1994. A quantitative study of calcium binding by isolated streptococcal cell walls and lipoteichoic acid: comparison with whole cells. J. Dent. Res. 73:1742-1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shapiro, L., A. M. Fannon, P. D. Kwong, A. Thompson, M. S. Lehmann, G. Grubel, J. F. Legrand, J. Als-Nielsen, D. R. Colman, and W. A. Hendrickson. 1995. Structural basis of cell-cell adhesion by cadherins. Nature 374:327-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith, R. J. 1995. Calcium and bacteria. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 37:83-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stoodley, P., K. Sauer, D. G. Davies, and J. W. Costerton. 2002. Biofilms as complex differentiated communities. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56:187-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stratford, M. 1992. Yeast flocculation: reconciliation of physiological and genetic viewpoints. Yeast 8:25-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stratford, M., and A. T. Carter. 1993. Yeast flocculation: lectin synthesis and activation. Yeast 9:371-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strynadka, N. C., and M. N. James. 1989. Crystal structures of the helix-loop-helix calcium-binding proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 58:951-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sutherland, I. 2001. Biofilm exopolysaccharides: a strong and sticky framework. Microbiology 147:3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Torres, A. G., N. T. Perna, V. Burland, A. Ruknudin, F. R. Blattner, and J. B. Kaper. 2002. Characterization of Cah, a calcium-binding and heat-extractable autotransporter protein of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 45:951-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ubeda, C., M. A. Tormo, C. Cucarella, P. Trotonda, T. J. Foster, I. Lasa, and J. R. Penades. 2003. Sip, an integrase protein with excision, circularization and integration activities, defines a new family of mobile Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity islands. Mol. Microbiol. 49:193-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valle, J., A. Toledo-Arana, C. Berasain, J. M. Ghigo, B. Amorena, J. R. Penades, and I. Lasa. 2003. SarA and not sigma B is essential for biofilm development by Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1075-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walstra, P., R. Jenness, and H. T. Badings. 1984. Dairy chemistry and physics. Wiley, New York, N.Y.

- 52.Waltersson, Y., S. Linse, P. Brodin, and T. Grundstrom. 1993. Mutational effects on the cooperativity of Ca2+ binding in calmodulin. Biochemistry 32:7866-7871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wessel, G. M., L. Berg, D. L. Adelson, G. Cannon, and D. R. McClay. 1998. A molecular analysis of hyalin—a substrate for cell adhesion in the hyaline layer of the sea urchin embryo. Dev. Biol. 193:115-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson, J. J., O. Matsushita, A. Okabe, and J. Sakon. 2003. A bacterial collagen-binding domain with novel calcium-binding motif controls domain orientation. EMBO J. 22:1743-1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]