Abstract

We have previously reported that Nef specifically interacts with a small but highly active subpopulation of p21-activated kinase 2 (PAK2). Here we show that this is due to a transient association of Nef with a PAK2 activation complex within a detergent-insoluble membrane compartment containing the lipid raft marker GM1. The low abundance of this Nef-associated kinase (NAK) complex was found to be due to an autoregulatory mechanism. Although activation of PAK2 was required for assembly of the NAK complex, catalytic activity of PAK2 also promoted dissociation of this complex. Testing different constitutively active PAK2 mutants indicated that the conformation associated with p21-mediated activation rather than kinase activity per se was required for PAK2 to become NAK. Although association with PAK2 is one of the most conserved properties of Nef, we found that the ability to stimulate PAK2 activity differed markedly among divergent Nef alleles, suggesting that PAK2 association and activation are distinct functions of Nef. However, mutations introduced into the p21-binding domain of PAK2 revealed that p21-GTPases are involved in both of these Nef functions and, in addition to promoting PAK2 activation, also help to physically stabilize the NAK complex.

The Nef protein is a 25- to 34-kDa accessory protein of primate immunodeficiency viruses (i.e., human/simian immunodeficiency virus [HIV/SIV]) and a major determinant of in vivo pathogenicity of these lentiviruses. Nef promotes viral replication via numerous, but incompletely understood strategies (13, 14). Nef has been found in lipid rafts (35), which are important microdomains in signal transduction. Nef modulates cellular signaling events, downregulates major histocompatibility complex class I and CD4 cell surface expression, and contributes to the infectivity of virus particles (7, 27). One potentially important cellular effector of Nef is the Nef-associated serine/threonine kinase (NAK) (23, 30), later identified as p21-activated kinase 2 (PAK2) (1, 25). The interaction between Nef and PAK2 takes place in a multiprotein complex (12) and critically depends on the stabilizing effects of other components of this complex, which remain unidentified but apparently include at least one protein that can bind to the SH3 domain-binding site of Nef (21). NAK has been implicated as an effector of Nef in inhibition of Bad-mediated apoptotic death and in increasing virus production in HIV-infected cells (19, 36).

The PAKs are mammalian homologues of yeast Ste20-like protein kinases and can be divided into two subfamilies: PAK-1, -2, and -3 (the PAK-I subfamily) and PAK-4, -5, and -6 (the PAK-II subfamily). Signaling via PAKs is involved in regulation of actin cytoskeleton, apoptosis, and malignant transformation (2, 5, 11, 16, 33, 34). Catalytic activation of PAKs typically results from binding of the GTP-loaded Rho p21-GTPases Cdc42 or Rac1 to the Cdc42/Rac interaction/binding (CRIB) domain (also known as p21-binding domain) located in the N-terminal regulatory domain. This binding relieves its autoinhibitory contacts with the C-terminal kinase domain and is followed by phosphorylation on Thr402 (PAK2; Thr423 in PAK1), as well as other key autophosphorylation sites and kinase activation (4, 22).

In addition to a net increase in cellular GTPase activity, PAKs may also be activated by their increased recruitment toward active GTPases, for example, by Nck-mediated plasma membrane targeting of PAK1 (3, 20). On the other hand, Cdc42-independent activation mechanisms induced by lipids, such as sphingosine, have been reported for both PAK1 and PAK2 (3, 28). Sphingosine stimulation can induce a similar level of activity as do p21-GTPases, as well as a similar pattern of autophosphorylation, and is associated with translocation of PAK2 to a membrane-containing cellular fraction (28).

Among the total cellular pool of PAK2, only a small but highly active fraction associates with Nef (1, 26). Because of the selective association of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) Nef with the catalytically active fraction of cellular PAK2, we have undertaken here a detailed analysis of the relationships between p21-GTPase binding, catalytic activity, subcellular localization, and association with Nef by PAK2. These results provide new insights into the role of p21-GTPases in Nef/PAK2 complex formation, as well as in the process of PAK activation itself.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and transient transfections.

293T human embryonic kidney fibroblast-derived cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and Glutamax. Transfections were performed by using Lipofectamine transfection reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection.

Plasmid constructs.

The generation of PAK2-HH (H82/85L) and PAK2-T402E has been described earlier (26). The PAK2 mutants ISP (I74N/S75P/P77A), E115K, and D125R were made by overlap PCR with a specific mutant primer pair and common outer primers containing restriction sites for cloning. All constructs were cloned into pEBB-ME with BamHI-KpnI to generate a multiepitope (ME)-tagged construct (26). The PAK2 double mutants with E115K or D125R mutations combined to HH or ISP mutations were made by cloning the HH- or ISP-mutated N-terminal fragment to the pEBB-PAK2-ME vector containing the respective autoinhibitory mutation. All constructs were confirmed by sequencing. The expression plasmid for dominant active Cdc42V12 was kindly provided by B. Mayer. pEBB-NL4-3-Nef R71 has been described previously (29). All divergent Nef alleles were cloned into pCG plasmid, and they are described elsewhere (15), except for HIV-2 cbl and SIV SYK51. HIV-2 cbl Nef was amplified from an HIV-2-infected culture obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. The Nef allele SYK51 was kindly provided by Beatrice Hahn (Department of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham [B. Hahn, unpublished data]).

Cell lysates and fractionation.

To obtain whole-cell lysates, cells were washed once with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and suspended in in vitro kinase assay (IVKA) lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg of aprotinin/ml). After 10 min on ice, the extract was centrifuged (13,000 rpm, 10 min), and the supernatant was collected. For fractionation of PAK2 into cytosolic and particulate fractions, cells were washed with PBS, suspended in hypotonic buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA) for 10 min on ice, and homogenized by 20 strokes with a Dounce homogenizer. After centrifugation (13,000 rpm for 10 min) the supernatant was collected. The particulate fraction was washed once with hypotonic buffer and resuspended in IVKA lysis buffer. After 10 min on ice, the extract was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min, and the solubilized particulate fraction was collected.

Raft fractionation by membrane flotation.

Cells were washed once with PBS and lysed with ice-cold isolation buffer (150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg of aprotinin/ml). After 20 min incubation on ice, samples were cleared by centrifugation (1,000 × g, 10 min). Lysates were adjusted to 40% Optiprep (Life Technologies), pipetted into Sorvall TH-660 centrifuge tubes, overlaid with 2.5 ml of 28% Optiprep in isolation buffer and with 0.6 ml of isolation buffer, and centrifuged for 3 h at 35,000 rpm at 4°C. Eight 500-μl fractions were collected from the top and subjected to immunoprecipitations with anti-Myc or anti-Nef antisera followed by IVKA analysis. A small part of each immunoprecipitate was boiled in sample buffer, separated in 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels, and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane for Western blot analysis. From each fraction, 50 μl was transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes by slot blotting and probed with 200 ng of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated cholera toxin (CTx; Sigma)/ml to detect the raft marker GM1.

Immunoprecipitations and IVKAs.

Immunoprecipitations with anti-Myc (9E10), anti-AU1 (Babco, Richmond, Calif.), or a monoclonal antibody (2F2; FIT Biotech, Tampere, Finland) and subsequent IVKAs with [γ-32P]ATP were performed as described previously (26). To visualize the autophosphorylation activity of PAK2, a fraction of the kinase assay was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and exposed to X-ray film.

RESULTS

Nef association depends on the molecular mechanism of PAK2 activation.

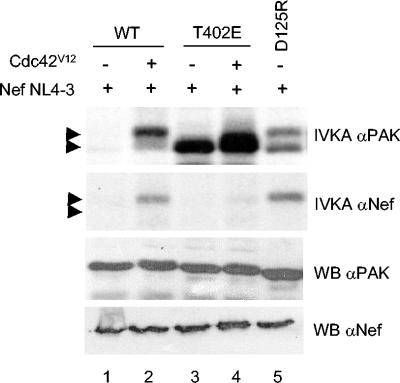

Mutations affecting acidic residues in the regulatory domain of PAK1 have been shown to result in a constitutively active kinase by disrupting intramolecular autoinhibitory interactions that suppress the catalytic domain (18, 38). Here, we have produced constitutively active PAK2 variants by mutating the corresponding residues in it (E115K and D125R) or, alternatively, by a strategy commonly applied to generate constitutively active protein kinases, namely, acidic replacement of a key phosphorylation site in the kinase activation loop (T402). 293T cells were transfected with wild-type or different constitutively active PAK2 variants and HIV-1 NL4-3 Nef, together or without the dominant active p21-GTPase (Cdc42V12). In accordance with our previous data (26), when wild-type PAK2 was used, Nef-associated PAK2 activity (i.e., NAK) was only observed if Cdc42V12 was cotransfected (Fig. 1, lanes 1 and 2). Thus, under the experimental conditions used here, the NL4-3 Nef allele did not substitute Cdc42V12 as a PAK2 activator. Unlike wild-type PAK2, however, the constitutively active PAK2 derivatives carrying mutations in the amino-terminal regulatory region (E115K or D125R) readily associated with this Nef allele also without Cdc42V12 cotransfection (Fig. 1; see also Fig. 5).

FIG. 1.

Activation-dependent association of PAK2 with Nef. 293T cells were transfected with HIV-1 NL4-3 Nef, together with wild-type (WT) PAK2 or constitutively active PAK2 variants (D125R and T402E). In some transfections Cdc42V12 was also included, as indicated in the figure. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc-tag antibodies (αPAK; top panel) or anti-Nef antibodies (α-Nef; middle panel), followed by an IVKA in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. The expression of total PAK2 and Nef proteins was detected by Western blotting (WB αPAK and WB αNef, respectively).

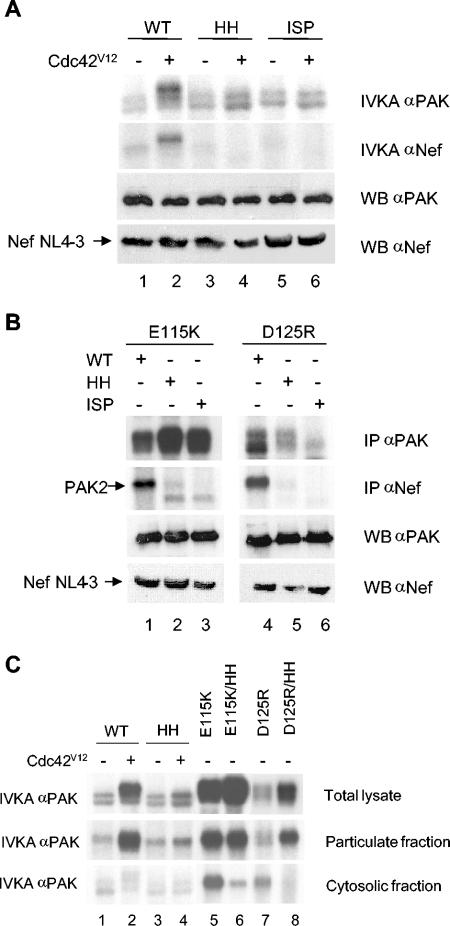

FIG. 5.

Cdc42-binding in the association of PAK2 with Nef and localization to the particulate fraction. (A) CRIB domain of PAK2 is essential for Nef association. Nef and wild-type (WT) PAK2 or different Cdc42-binding deficient mutants, PAK2-HH or PAK2-ISP, were transfected, together with Cdc42V12, where indicated. Total PAK2 activity (top panel) and Nef-associated PAK2 activity (bottom panel) were studied by anti-Myc (for PAK2) or anti-Nef immunoprecipitations and IVKA. Expression of PAK2 and Nef proteins was studied by Western blotting (WB αPAK and WB αNef). (B) Release of autoinhibition does not substitute for Cdc42-binding deficiency for association with Nef. Total PAK2 activity (top panel) and Nef-associated PAK2 activity were studied as in panel A from cells that were transfected with Nef and PAK2-E115K or PAK2-D125R either with a functional (WT) or mutated (HH or ISP) CRIB motif. (C) Membrane localization of PAK2 is Cdc42-binding independent. Wild-type (WT) PAK2, different activated mutants (E115K and D125R), or Cdc42-binding-deficient mutants (HH, E115K/HH, and D125R/HH) were transfected. Total cell lysates, as well as the particulate and cytosolic fractions, were collected from these cells, and the total PAK2 activity was studied from both fractions as in panel A.

Interestingly, a very different picture was seen when the PAK2 mutant T402E was tested. In contrast to the PAK2 mutants defective in autoinhibition, PAK2-T402E failed to associate with Nef in the absence or presence of cotransfected Cdc42V12 (Fig. 1, lanes 3 and 4). Thus, the molecular mechanism underlying PAK2 activation can determine whether or not PAK2 associates with Nef. Conformation associated with PAK2 activation via loss of inhibitory contacts between its N- and C-terminal domains, rather than catalytic activity per se, therefore appears to be critical for driving Nef/PAK2 complex formation.

Nef alleles differ greatly in their capacity to stimulate PAK2 activity.

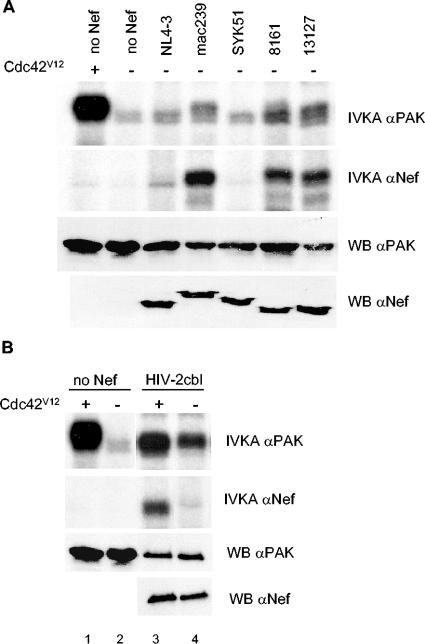

The requirement of NL4-3 Nef to precipitate NAK activity in the absence of Cdc42V12 or an appropriate activating mutation in PAK2 suggested that this Nef allele was unable to stimulate PAK2 activity in the transfected cells. However, since previous studies have reported PAK activation by certain Nef alleles, such as SF2 (1), we addressed this question by examining PAK2 activity in cells transfected with PAK2 alone or together with different SIV, HIV-1, and HIV-2 Nef alleles. Figure 2 shows data on comparing NL4-3 Nef with a divergent panel of mainly primary Nef alleles. These Nef alleles have been recently extensively characterized for their functionality, and all were shown to be able to associate with PAK2 if cotransfected with Cdc42V12 (15). As can be seen from Fig. 2A, some of these alleles were equally poor PAK2 activators, as was NL4-3 Nef, whereas others could clearly stimulate the catalytic activity of cotransfected PAK2, some being almost as efficient as Cdc42V12 in this function.

FIG. 2.

(A) Capacity to stimulate PAK2 activity differs among Nef alleles. PAK2 was transfected into 293T alone (no Nef) with or without Cdc42V12 or together with one of the indicated HIV-1 and SIV Nef alleles. 8161 and 13127 are both HIV-1 subtype-O Nef alleles. Total (IVKA αPAK) and Nef-associated (IVKA αNef) kinase activity of PAK2 from these cells was studied as in Fig. 1. The total amount of PAK2 and Nef protein in each lysate was examined by Western blotting (WB αPAK and αNef). (B) Despite a capacity to activate PAK2, HIV-2 cbl Nef depends on Cdc42V12 to associate with PAK2. PAK2 alone or with HIV-2 cbl Nef was transfected into 293T cells with or without Cdc42V12 and analyzed for total and Nef-associated PAK2 kinase activity as in panel A.

This differing capacity to activate PAK2 was even more striking when NAK activity (i.e., PAK2 activity coprecipitated with Nef antibodies) in the absence of cotransfected Cdc42V12 was examined. Nef alleles such as mac239, 8161, and 13127, capable of inducing kinase activity in anti-PAK2 immunocomplexes, were also associated with intense NAK activity. Thus, the capacity to stimulate PAK2 activity clearly differs greatly among Nef alleles, which is in contrast to the virtually uniform ability of divergent Nef alleles to associate and coprecipitate activated PAK2 (15).

Intrestingly, however, HIV-2 cbl Nef, which was one of the most potent PAK2 activators among this panel of Nef alleles (Fig. 2B, lane 4, of panel IVKA αPAK), coprecipitated only modest amounts of NAK activity (Fig. 2B, lane 4, of panel IVKA αNef). As observed previously (15), when Cdc42V12 was cotransfected HIV-2 cbl Nef efficiently precipitated NAK activity (Fig. 2B, lane 3, of panel IVKA αNef). Thus, despite its capacity to activate PAK2 HIV-2 cbl Nef remained dependent on Cdc42V12 for efficient association with activated PAK2, possibly reflecting the dual role of p21-GTPases in NAK complex formation described elsewhere in this study (see discussion of the role of Cdc42 in Nef/PAK interaction below).

The different patterns of the Nef alleles tested here in stimulating cellular PAK2 activity and in associating with PAK2 clearly indicate that these are distinct and separable functions of Nef. Indeed, the failure of some Nef alleles (such as NL4-3) to stimulate PAK2 activity despite their capacity to associate with (preactivated) PAK2 demonstrates that, unlike p21-GTPases, Nef does not activate PAK2 as a direct consequence of binding.

This feature of NL4-3 Nef (its dependence for Cdc42V12 or activating mutations in PAK2 in order to assemble a NAK complex) also provides a practical means to specifically study questions related to Nef/PAK2 complex assembly independently of effects of Nef on PAK2 activity, which is the experimental strategy that we have used in the studies described below.

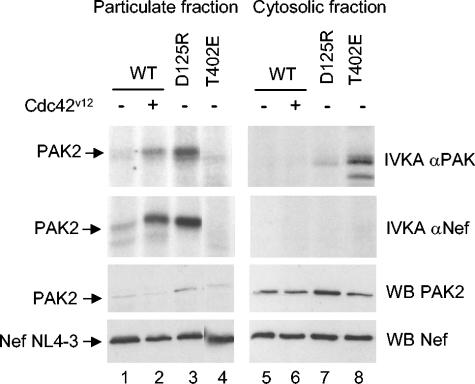

Nef/PAK2 complex associates with membrane rafts.

Due to myristoylation of its N terminus, a significant fraction of Nef is associated with cellular membranes (37). On the other hand, a subpopulation of cellular PAK2 becomes recruited to membranes upon activation (20, 28). Considering the dependence of Nef/PAK2 complex formation on PAK2 activation, it was therefore of interest to study the cellular compartment in which Nef/PAK2 interaction takes place. To this end, we transfected cells with NL4-3 Nef and different PAK2 variants and compared the relative amounts of PAK2 protein and PAK2 or NAK activity in the cytosolic and particulate (membrane) fractions. Notably, PAK2 activity was highly enriched in the particulate fraction in all cases, except for PAK2-T402E, whose activity was mainly cytosolic (Fig. 3, panels labeled IVKA αPAK). In contrast to kinase activity, the bulk of PAK2 protein was in all cases found in the cytosol (Fig. 3, panels labeled WB αPAK2). In accordance, immunoprecipitation of the same fractions with an anti-Nef-antibody detected NAK activity only in the particulate fraction (Fig. 3, panels labeled IVKA αNef). On the other hand, Nef protein was found in both fractions (Fig. 3, panels labeled WB αNef). Notably, no NAK signal was detected from the cytosolic fraction even in the case of PAK2-T402E, whose activity was mainly found in this fraction. Thus, we conclude that NAK complex is restricted to cell membranes. However, this is probably not the sole reason for the failure of PAK2-T402E to associate with Nef, because this situation was not remedied when PAK2-T402E was artificially targeted to the membranous fraction by attaching a CAAX-box element to its C terminus (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Membrane localization of PAK2 and NAK activity. NL4-3 Nef and wild-type PAK2 or different activated mutants were transfected with or without Cdc42V12 as indicated. Cell lysates were fractionated into particulate (left panels) and cytosolic (right panels) fractions. Part of both fractions was subjected to Western blotting analysis (two bottom panels) with antibodies against PAK2 and Nef. The rest of the fractions were used for immunoprecipitation analysis of total (IVKA αPAK) and Nef-associated (IVKA αNef) PAK2 activity as in Fig. 1.

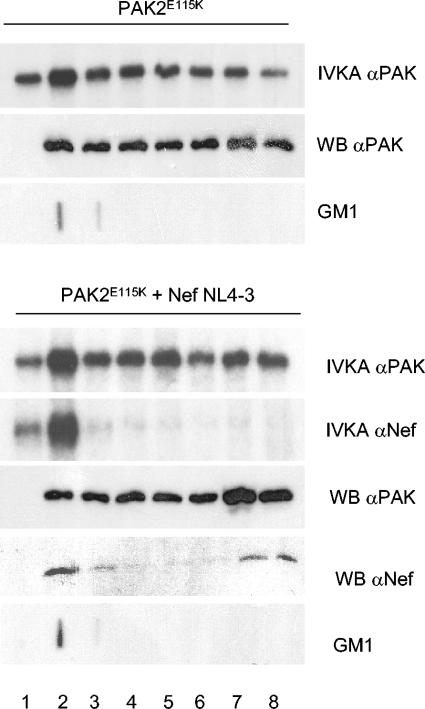

Lipid rafts remain insoluble after treatment with 1% Triton X-100 and can be enriched to low-density fractions by flotation ultracentrifugation. Since localization of Nef in rafts has been demonstrated earlier (35), we transfected cells with the active PAK2 variant E115K with or without Nef (Fig. 4, lower or upper panels, respectively) to study whether partitioning of NAK activity to the particulate fraction was due to its raft association. Successful flotation of rafts was confirmed by detection of the raft marker ganglioside GM1 by using labeled CTx (Fig. 4, panels labeled GM1). In fractionation, PAK2 protein was not enriched in rafts and instead was detected in all fractions, including the bottom ones (fractions 5 to 8 in Fig. 4) in accordance with its mainly cytosolic localization shown in Fig. 3. In contrast, PAK2 activity was enriched in the GM1-containing fractions and less abundant in the bottom fractions. However, raft association of PAK2 activity was much less striking than its highly selective association with the membraneous fraction (Fig. 3), indicating that at least two-thirds of PAK2 activity is associated with membranes other than rafts. A similar but more pronounced raft association of PAK activity was recently reported by Krautkramer et al. (17). Their data also suggested a marked role for Nef in recruiting PAK to rafts, which was not evident in our experiments.

FIG. 4.

Nef associates with PAK2 in a raft-containing membrane population. Lysates of cells transfected with PAK2-E115K with or without Nef NL4-3 were subjected to membrane floatation on Optiprep gradient centrifugation. Eight fractions (starting from top; lanes 1 to 8) were collected and analyzed for total (IVKA αPAK2) and Nef-associated (IVKA αNef) PAK2 activity as in Fig. 2. PAK2 and Nef protein expression in these fractions was examined by Western blotting (WB αPAK and WB αNef), whereas the raft marker GM1 present in these fractions was detected by slot blotting and visualization with labeled CTx subunit B (GM1).

Interestingly, however, NAK activity was exclusively found in fractions 1 and 2 (Fig. 4B, panel labeled IVKA αNef), suggesting that NAK activity is more selectively associated with rafts than is total PAK2 activity. In agreement with previously published data (35, 39), a subpopulation (estimated 20%) of Nef protein localized to rafts but was also found in other fractions (Fig. 4, panel labeled WB αNef). Thus, the selective localization of the NAK complex to the rafts cannot be explained simply by the lack of Nef and PAK2 in other subcellular compartments.

Role of Cdc42 in Nef/PAK2 interaction.

The Cdc42/Rac-binding domain (CRIB) connects PAKs to these p21-GTPases, and mutations introduced to CRIB abolish p21-mediated stimulation of PAK activity (38). We have previously noticed that leucine substitution of two critical histidine residues (H82 and H85) in the CRIB domain of PAK2 (mutant dubbed PAK2-HH) prevented Nef/PAK2 complex formation (26). Therefore, a question arises whether the CRIB motif dependence of NAK complex is due to lack of p21-mediated PAK2 activation or a direct consequence of the loss of Cdc42V12/PAK2 interaction.

To address this issue, we first constructed another p21-binding deficient PAK2 mutant containing amino acid substitutions in three other critical CRIB motif residues (I74N;S75P;P77A [38], mutant dubbed PAK2-ISP). PAK2-ISP failed to associate with Nef (Fig. 5A, bottom panel, lanes 3 to 6), confirming the observation made with PAK2-HH and therefore supporting the idea that these mutations probably affected Nef association by PAK2 specifically by preventing p21 binding. Because the constitutively active PAK2-E115K and PAK2-D125R could associate with NL4-3 Nef without Ccd42V12 cotransfection (Fig. 1 and 5), we created PAK2 double mutants containing both a conformationally activating mutation (E115K or D125R) and a CRIB-inactivating mutation (HH or ISP). However, even when combined with D125R or E115K mutation, HH- and ISP-mutated PAK2 variants still failed to associate with Nef (Fig. 5B, lanes 2 and 3 and lanes 5 and 6). Since the formation of the Nef/PAK2 complex was found to be restricted to cellular membranes, the failure of the E115K/HH and D125R/HH combination mutants to associate with Nef could simply reflect their inability to localize to cell membranes. When the subcellular localization of these double mutants was examined, however, their activity was found to be equally or even more selectively membrane-associated compared to E115K and D125R with intact CRIB motifs (Fig. 5C, lanes 5 to 8).

These data show that a functional CRIB domain is required for NAK complex formation for reasons that cannot be assigned only to its enabling p21-mediated activation of PAK2. A plausible explanation for this observation would be that a p21-GTPase is physically involved in stabilization of the Nef/PAK2 complex. Since PAK2-E115K and PAK2-D125 with an intact CRIB motif could associate with NL4-3 Nef without Cdc42V12 cotransfection, enough endogenous active p21-GTPases appear to be present in the lipid rafts of these cells to help in stabilizing the NAK complex, although this low p21-GTPase activity is insufficient to drive activation and membrane relocalization of native PAK2.

Kinase activity of PAK2 promotes disassembly of the Nef/PAK2 complex.

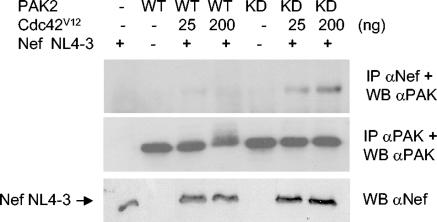

Nef efficiently associates with the catalytically active subpopulation of PAK2, but this represents only a small fraction of total cellular PAK2 protein (1, 26). As a consequence, sensitive immunocomplex phosphorylation assays (Fig. 1 to 5) have until now been the only practical means to study the NAK complex. The notion that a p21-GTPase may be directly involved in Nef/PAK2 complex formation (Fig. 6) led us to hypothesize that this interaction might take place during the process of PAK2 activation and fall apart after the kinase activity of PAK2 has been induced.

FIG. 6.

Kinase activity of PAK2 destabilizes the NAK complex. Nef and wild-type (WT) PAK2 or the kinase-dead (KD) PAK2-K278R variant were cotransfected, together with increasing amounts of Cdc42V12 as indicated. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Nef or anti-PAK2 antibodies, followed by anti-PAK2 Western blotting to visualize Nef-associated (IP αNef) and total (IP αPAK) PAK2. Expression of total Nef protein in each lysate was examined by Western blotting (WB αNef).

To test this idea, we examined whether a kinase-deficient mutant of PAK2 (K278R) could associate more stably with Nef than wild-type PAK2. Indeed, by cotransfecting increasing amounts of Ccd42V12, together with PAK2-K278R, a corresponding increase in PAK2 coprecipitation with Nef could be observed by Western blotting (Fig. 6). This result supports the idea that catalytic activity of PAK2 is involved in destabilizing the NAK complex and shows that using a kinase-defective PAK2 results in accumulation of a sufficient amount of Nef/PAK2 complex in cells and that this interaction can be visualized by a traditional coprecipitation/immunoblotting approach. In contrast, the amount of wild-type PAK2 coprecipitating under these conditions was too small to be consistently detected, even when the highest amount (200 ng) of Cdc42V12 expression vector was cotransfected. Attempts to increase the association between wild-type PAK2 and Nef by transfecting even larger amount of Cdc42V12 have not been successful and have instead resulted in substantially decreased PAK2 protein levels (data not shown), possibly through increased PAK2 degradation and/or cytostasis (10).

DISCUSSION

We have previously reported that Nef selectively associates with catalytically active PAK2, but the role of Nef-induced PAK activation in assembly of the NAK complex has remained unclear. NAK activity in anti-Nef immunocomplexes has been commonly interpreted as evidence of a capacity of Nef to stimulate PAK activity, but few studies have directly addressed this issue. Recently, Arora et al. reported that an increase in PAK2 kinase activity could be demonstrated in SF2 Nef-transfected cells compared to control-transfected cells (1). However, results of similar experiments by us with the NL4-3 Nef allele (26) (Fig. 1) have been negative and less than convincing when SF2 Nef was used (unpublished data). By testing a panel of diverse Nef alleles we show here that Nef should indeed be considered a PAK2 activator, but this property is weak or lacking in many Nef alleles available for study. Most of the Nef alleles that showed potent PAK2 activation were molecular clones isolated without passage of the virus in cell culture. Although this correlation is not sufficient for drawing any conclusions, it is possible that potent PAK2 activation by Nef might for some reason be counterselected during in vitro growth. In any case, given that some Nef alleles clearly have a capacity to stimulate PAK2 activity, the differing results obtained with “weaker” alleles may simply have reflected differences in assay sensitivity.

Unlike the varying capacity of Nef alleles to promote PAK2 kinase activity, the ability to associate with active PAK2 is a highly conserved Nef function (15, 26, 31). Therefore, a failure to stimulate PAK2 activity rather than a failure to associate with the NAK complex probably explains the lack of serine/threonine kinase activity reported to be associated with some Nef alleles. The segregation of these properties among different Nef alleles also implicates that these two Nef functions are mechanistically distinct. Thus, Nef is not mimicking an active p21-GTPase, which acts by pushing PAK2 into an active conformation via binding to its CRIB motif. Instead, Nef appears to act upstream of the p21-GTPase to promote their capacity to stimulate PAK2 activation. This scenario agrees with the model proposed based on studies from the Peterlin laboratory, where Nef acts as an adaptor to recruit proteins, including phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Vav into a “signalosome” in which PAK activation could occur (9, 19, 24). On the other hand, an alternative model was recently proposed by a study from the Skowronski laboratory, which reported that Nef stimulates cellular guanine nucleotide exchange factor activity and consequently p21-GTPase-regulated signaling cascades by associating with the DOCK2/ELMO1 complex (12). Of course, these two models need not to be mutually exclusive, and Nef might possess redundant strategies for stimulating cellular p21-GTPases.

When the terms “upstream” and “downstream” are used to describe effects of Nef on cellular signaling, it is important to note that they refer to the order of events but do not imply that these processes would have to be spatially separated. Indeed, the dual role of Cdc42V12 revealed by the present study suggests that, although PAK2 activation and association are mechanistically distinct functions of Nef, they take place in the same multiprotein complex. Specifically, we found that, apart from enabling conformational activation of PAK2, its CRIB motif served an additional important role in the Nef/PAK2 complex. This suggested that an active p21-GTPase is also physically involved in stabilizing the NAK complex. Moreover, the idea that PAK2 activation and association by Nef involve a common protein assembly is also supported by the fact that Nef-induced increase in cellular p21-GTPase activity results in selective activation of PAK2 but not PAK1 (1)[our unpublished data], although Cdc42 and Rac1 have no intrinsic preferences as activators of these two PAK family kinases.

Our fractionation studies revealed that the NAK complexes are restricted to membrane domains known as lipid rafts. Such raft specificity is striking, since active PAK2 as well as Nef could also be found in most other membrane fractions. This observation might be explained by the critical role of lipid rafts in regulation of the cellular activity of the p21-GTPase Rac1 (6). Although active PAK2 may leave these membrane domains, the role of an active (GTP-bound) p21-GTPase in stabilizing the Nef/PAK2 interaction could account for restriction of this complex to rafts.

Another factor that was found to contribute to limiting the NAK activity close to its origin, i.e., the membrane-associated p21-GTPase-containing activation complex, was the apparent destabilizing effect of PAK2 kinase activity on the NAK complex. This suggested a model where a p21-GTPase is required for assembly of the NAK complex, but CRIB-mediated catalytic activation of PAK2 subsequently promotes rapid dissociation of this complex. This dynamic and transient nature of the NAK complex could also explain its low abundance even when Nef and PAK2 are overexpressed in cells. This scenario was suggested by the observation that cotransfection of Nef and Cdc42V12 together with a kinase-deficient PAK2 mutant (K278R) led to a significantly more stable Nef/PAK2 complex. Indeed, Nef/PAK2-K278R interaction could be readily demonstrated by a standard coimmunoprecipitation and Western blot procedure, which has been difficult in the case of a regular NAK complex. This approach should provide new experimental opportunities for elucidation of the functional role of the Nef/PAK2, for example, by facilitating proteomics studies aimed at complete characterization of the proteins required for the assembly and involved in effector functions of the NAK complex.

Despite its constitutive catalytic activity PAK2-T402E differed starkly from PAK2 activated by mutations that mimic the effect of p21 binding (E115K and D125R) in that it failed to associate with Nef as well as with cell membranes. We speculate that such direct activation of the PAK2 catalytic apparatus by the T402E mutation may result in a conformation/autophosphorylation pattern that differs from PAK2 activated via a physiological p21-GTPase-mediated mechanism. As a consequence of its aberrant conformation PAK2-T402E might be unable to support an interaction(s) that normally couples activated PAK2 to its membrane-associated partners. Whatever the reason, the strikingly different biological behavior of these two different types of dominantly active PAK2 mutants has important implications for future research on Nef/PAK2 interaction, as well as on PAK family kinases in general. Although it is obvious that only PAK2-E115K and PAK2-D125R but not PAK2-T402E can be used as a “dominant active NAK,” our data also suggest that the choice of the activating mutation is also likely to profoundly influence studies on other aspects of PAK in cell biology.

Protection from cell death via NAK-mediated phosphorylation and inactivation of the proapoptotic Bad protein has been described as an important function of Nef, which could in part explain its pathogenic effect in HIV infection (36). NAK has also been implicated as an effector of Nef in increasing HIV gene expression and virion production in the infected cells (8, 32) and thus represents a potentially useful therapeutic target. Detailed understanding of the composition and function of the NAK multiprotein complex could allow the design of compounds that would target a cellular (and hence nonmutating) factor and thereby specifically block Nef-mediated PAK2 activation without interfering with the normal functions of this important kinase.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Medical Research Fund of Tampere University Hospital to K.S. (project 9B074) and G.H.R. (project 9C172) and from the Academy of Finland to G.H.R. (projects 49299 and 202423) and K.S. (project 44499) and by grant Biomed FP5 QLK-CT-2000-01630 from the European Union. K.P. is supported by Tampere University Graduate School in Biomedicine and Biotechnology.

We thank Oliver Fackler for discussions and sharing unpublished data on Nef and lipid rafts. We are grateful to Kristina Lehtinen for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arora, V. K., R. P. Molina, J. L. Foster, J. L. Blakemore, J. Chernoff, B. L. Fredericksen, and J. V. Garcia. 2000. Lentivirus Nef specifically activates Pak2. J. Virol. 74:11081-11087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagrodia, S., and R. A. Cerione. 1999. Pak to the future. Trends Cell Biol. 9:350-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bokoch, G. M., A. M. Reilly, R. H. Daniels, C. C. King, A. Olivera, S. Spiegel, and U. G. Knaus. 1998. A GTPase-independent mechanism of p21-activated kinase activation: regulation by sphingosine and other biologically active lipids. J. Biol. Chem. 273:8137-8144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chong, C., L. Tan, L. Lim, and E. Manser. 2001. The mechanism of PAK activation: autophosphorylation events in both regulatory and kinase domains control activity. J. Biol. Chem. 276:17347-17353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniels, R. H., and G. M. Bokoch. 1999. p21-activated protein kinase: a crucial component of morphological signaling? Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:350-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.del Pozo, M. A., N. B. Alderson, W. B. Kiosses, H. H. Chiang, R. G. Anderson, and M. A. Schwartz. 2004. Integrins regulate Rac targeting by internalization of membrane domains. Science 303:839-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fackler, O. T., and A. S. Baur. 2002. Live and let die: Nef functions beyond HIV replication. Immunity 16:493-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fackler, O. T., X. Lu, J. A. Frost, M. Geyer, B. Jiang, W. Luo, A. Abo, A. S. Alberts, and B. M. Peterlin. 2000. p21-activated kinase 1 plays a critical role in cellular activation by Nef. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:2619-2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fackler, O. T., W. Luo, M. Geyer, A. S. Alberts, and B. M. Peterlin. 1999. Activation of Vav by Nef induces cytoskeletal rearrangements and downstream effector functions. Mol. Cell 3:729-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang, Z., J. Ling, and J. A. Traugh. 2003. Localization of p21-activated protein kinase gamma-PAK/Pak2 in the endoplasmic reticulum is required for induction of cytostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 278:13101-13109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaffer, Z. M., and J. Chernoff. 2002. p21-activated kinases: three more join the Pak. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 34:713-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janardhan, A., T. Swigut, B. Hill, M. P. Myers, and J. Skowronski. 2004. HIV-1 Nef binds the DOCK2-ELMO1 complex to activate Rac and inhibit lymphocyte chemotaxis. PLoS Biol. 2:65-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kestler, H. W., III, D. J. Ringler, K. Mori, D. L. Panicali, P. K. Sehgal, M. D. Daniel, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1991. Importance of the nef gene for maintenance of high virus loads and for development of AIDS. Cell 65:651-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirchhoff, F., T. C. Greenough, D. B. Brettler, J. L. Sullivan, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1995. Brief report: absence of intact nef sequences in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive HIV-1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:228-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirchhoff, F., M. Schindler, N. Bailer, G. H. Renkema, K. Saksela, V. Knoop, M. C. Müller-Trutwin, M. L. Santiago, F. Bibollet-Ruche, M. T. Dittmar, J. L. Heeney, B. H. Hahn, and J. Münch. 2004. Nef proteins from simian immunodeficiency virus-infected chimpanzees interact with the p21-activated kinase 2 and modulate cell surface expression of various human receptors. J. Virol. 78:6864-6874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knaus, U. G., and G. M. Bokoch. 1998. The p21Rac/Cdc42-activated kinases (PAKs). Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 30:857-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krautkramer, E., S. I. Giese, J. E. Gasteier, W. Muranyi, and O. T. Fackler. 2004. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef activates p21-activated kinase via recruitment into lipid rafts. J. Virol. 78:4085-4097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lei, M., W. Lu, W. Meng, M. C. Parrini, M. J. Eck, B. J. Mayer, and S. C. Harrison. 2000. Structure of PAK1 in an autoinhibited conformation reveals a multistage activation switch. Cell 102:387-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linnemann, T., Y. H. Zheng, R. Mandic, and B. M. Peterlin. 2002. Interaction between Nef and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase leads to activation of p21-activated kinase and increased production of HIV. Virology 294:246-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu, W., S. Katz, R. Gupta, and B. J. Mayer. 1997. Activation of Pak by membrane localization mediated by an SH3 domain from the adaptor protein Nck. Curr. Biol. 7:85-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manninen, A., M. Hiipakka, M. Vihinen, W. Lu, B. J. Mayer, and K. Saksela. 1998. SH3-Domain binding function of HIV-1 Nef is required for association with a PAK-related kinase. Virology 250:273-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manser, E., T. Leung, H. Salihuddin, Z. S. Zhao, and L. Lim. 1994. A brain serine/threonine protein kinase activated by Cdc42 and Rac1. Nature 367:40-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nunn, M. F., and J. W. Marsh. 1996. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef associates with a member of the p21-activated kinase family. J. Virol. 70:6157-6161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plemenitas, A., X. Lu, M. Geyer, P. Veranic, M. N. Simon, and B. M. Peterlin. 1999. Activation of Ste20 by Nef from human immunodeficiency virus induces cytoskeletal rearrangements and downstream effector functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Virology 258:271-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renkema, G. H., A. Manninen, D. A. Mann, M. Harris, and K. Saksela. 1999. Identification of the Nef-associated kinase as p21-activated kinase 2. Curr. Biol. 9:1407-1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Renkema, G. H., A. Manninen, and K. Saksela. 2001. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef selectively associates with a catalytically active subpopulation of p21-activated kinase 2 (PAK2) independently of PAK2 binding to Nck or beta-PIX. J. Virol. 75:2154-2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Renkema, G. H., and K. Saksela. 2000. Interactions of HIV-1 NEF with cellular signal transducing proteins. Front. Biosci. 5:D268-D283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roig, J., P. T. Tuazon, and J. A. Traugh. 2001. Cdc42-independent activation and translocation of the cytostatic p21-activated protein kinase gamma-PAK by sphingosine. FEBS Lett. 507:195-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saksela, K., G. Cheng, and D. Baltimore. 1995. Proline-rich (PxxP) motifs in HIV-1 Nef bind to SH3 domains of a subset of Src kinases and are required for the enhanced growth of Nef+ viruses but not for down-regulation of CD4. EMBO J. 14:484-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawai, E. T., A. Baur, H. Struble, B. M. Peterlin, J. A. Levy, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 1994. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef associates with a cellular serine kinase in T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:1539-1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sawai, E. T., A. S. Baur, B. M. Peterlin, J. A. Levy, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 1995. A conserved domain and membrane targeting of Nef from HIV and SIV are required for association with a cellular serine kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 270:15307-15314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sawai, E. T., I. H. Khan, P. M. Montbriand, B. M. Peterlin, C. Cheng-Mayer, and P. A. Luciw. 1996. Activation of PAK by HIV and SIV Nef: importance for AIDS in rhesus macaques. Curr. Biol. 6:1519-1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schurmann, A., A. F. Mooney, L. C. Sanders, M. A. Sells, H. G. Wang, J. C. Reed, and G. M. Bokoch. 2000. p21-activated kinase 1 phosphorylates the death agonist bad and protects cells from apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:453-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang, Y., H. Zhou, A. Chen, R. N. Pittman, and J. Field. 2000. The Akt proto-oncogene links Ras to Pak and cell survival signals. J. Biol. Chem. 275:9106-9109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang, J. K., E. Kiyokawa, E. Verdin, and D. Trono. 2000. The Nef protein of HIV-1 associates with rafts and primes T cells for activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:394-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolf, D., V. Witte, B. Laffert, K. Blume, E. Stromer, S. Trapp, P. d'Aloja, A. Schurmann, and A. S. Baur. 2001. HIV-1 Nef associated PAK and PI3-kinases stimulate Akt-independent Bad-phosphorylation to induce antiapoptotic signals. Nat. Med. 7:1217-1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu, G., and R. L. Felsted. 1992. Effect of myristoylation on p27 nef subcellular distribution and suppression of HIV-LTR transcription. Virology 187:46-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao, Z. S., E. Manser, X. Q. Chen, C. Chong, T. Leung, and L. Lim. 1998. A conserved negative regulatory region in αPAK: inhibition of PAK kinases reveals their morphological roles downstream of Cdc42 and Rac1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:2153-2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zheng, Y. H., A. Plemenitas, T. Linnemann, O. T. Fackler, and B. M. Peterlin. 2001. Nef increases infectivity of HIV via lipid rafts. Curr. Biol. 11:875-879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]