Abstract

Latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a transforming protein that affects multiple cell signaling pathways and contributes to EBV-associated oncogenesis. LMP1 can be expressed in some states of EBV latency, and significant induction of full-length LMP1 is also observed frequently during virus reactivation into the lytic cycle. It is still unknown how LMP1 expression is regulated during the lytic stage and whether any EBV lytic protein is involved in the induction of LMP1. In this study, we first identified that LMP1 expression is associated with the spontaneous virus reactivation in EBV-infected 293 cells and that its expression is a downstream event of the lytic cycle. We further found that LMP1 can be induced by ectopic expression of Rta, an EBV immediate-early lytic protein. The Rta-mediated LMP1 induction is independent of another immediate-early protein, Zta. Northern blotting and reverse transcription-PCR analysis revealed that Rta upregulates LMP1 at the RNA level. Reporter gene assays further demonstrated that Rta activates both the proximal and distal promoters of the LMP1 gene in EBV-negative cells. Both the amino and carboxyl termini of the Rta protein are required for the induction of LMP1. In addition, Rta transactivates LMP1 not only in epithelial cells but also in B-lymphoid cells. This study reveals a new mechanism to upregulate LMP1 expression, expanding the knowledge of LMP1 regulation in the EBV life cycle. Considering an equivalent case of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, induction of a transforming membrane protein by a key lytic transactivator during virus reactivation is likely to be a conserved event for gammaherpesviruses.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection is associated with several human malignancies derived from lymphoid or epithelial cells, such as endemic Burkitt's lymphoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) (60). In addition, its infection immortalizes primary B lymphocytes in vitro into lymphoblastoid cell lines (35). Being a gammaherpesvirus, EBV has both latent and lytic states in its life cycle; the latent infection is predominant, while the lytic cycle can be conditionally reactivated (35). In latency, EBV can express a few so-called latent proteins, including six EBV nuclear antigens (EBNAs) and three latent membrane proteins (LMPs). When the EBV lytic cycle is induced, an expression cascade of numerous lytic genes occurs, resulting in the replication of viral genomes and the production of virus particles (35).

Among the EBV latent gene products, LMP1 is the most well-documented oncoprotein (35, 42). Not only is this integral membrane protein essential for EBV-induced immortalization of B lymphocytes, but expression of LMP1 alone can also cause transformation of rodent fibroblasts and other cells in vitro (34, 36, 72). In transgenic mice models, expression of LMP1 induces development of B-cell lymphoma or epidermal hyperplasia (37, 75). By functioning like a constitutively active, ligand-independent receptor, LMP1 triggers multiple cell signaling events including TRAF/TRADD/NF-κB, JNK/AP-1, MAPK/ATF2, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt, and JAK/STAT pathways (15-18, 24, 42). As the result of the abnormal activation of the cell signaling, LMP1 may upregulate expression of cellular genes involved in cell proliferation, antiapoptosis, cytokine secretion, angiogenesis, and tumor metastasis (17, 22, 36, 49, 51, 76). A recent study also shows that LMP1 may promote genomic instability of cells through repression of DNA repair (44).

When considering the oncogenic potentials of LMP1, how its expression is regulated in the EBV life cycle becomes an important issue. Transcription of the full-length LMP1 gene can be initiated from two promoters in the viral genome. ED-L1 is the proximal promoter, while TR-L1 is the distal one located further upstream, close to the terminal repeats (6, 29, 63). It has been noted that both viral and cellular factors regulate the activities of the LMP1 promoters during EBV latency. In EBV-immortalized B cells that express the whole spectrum of viral latent genes, EBNA2 plays a potent role in activating ED-L1 (33, 73). EBNA2-dependent activation of ED-L1 involves cellular proteins such as RBP-Jκ, PU.1, and ATF-2/c-Jun (33, 65), and the activation is further enhanced by two latent proteins, EBNA-LP and EBNA3C (54, 78). Alternatively, ED-L1 can be activated in an EBNA2-independent manner by several cellular proteins including Notch1, IRF7, STAT, USF, and ATF-1/CREB-1 (11, 28, 53, 65, 66). Activation of TR-L1 does not require EBNA2, and it has been shown that cellular Sp1/Sp3 or JAK/STAT signaling positively regulates the promoter (11, 63, 71). Another viral latent protein, EBNA1, can direct activation of both ED-L1 and TR-L1 through a distal enhancer (6, 23). It should be noted that some of the regulation mechanisms are cell type specific. For example, EBNA2- and EBNA1-mediated transactivation of LMP1 occurs in B cells but not in epithelial cells (6, 12, 20, 73). On the other hand, LMP1 is expressed at a very low level or even not at all in some states of EBV latency (10, 31, 62). DNA methylation or histone deacetylation may play important roles in the silencing of the LMP1 gene (50, 66).

In contrast to the knowledge of the regulatory mechanisms during EBV latency, little is known about how LMP1 expression is regulated in the lytic stage. Previous studies have shown that an amino-terminally truncated protein of LMP1 is detected during the reactivation of some EBV strains (4, 61). This truncated LMP1 is encoded by the transcripts initiated from an internal promoter within the first intron of the LMP1 gene by using an ATG at codon 129 as the translational start site (19, 29, 68). Many EBV strains, however, produce no such truncated protein in that they lack an ATG at codon 129 of LMP1 (19, 68). Furthermore, the truncated LMP1 shares no signaling or transforming activities of full-length LMP1 and is considered dispensable for the EBV life cycle and B-cell immortalization (19, 34, 68).

Instead of the truncated LMP1, we focused this study on the regulation of full-length LMP1 in the EBV lytic cycle. Notably, a significant increase of full-length LMP1 has been observed frequently when EBV reactivation is induced by various stimuli including cross-linking of surface immunoglobulin, virus superinfection, and treatment with phorbol ester, 5-azacytidine, n-butyrate, or histone deacetylase inhibitors (4, 10, 13, 62, 66, 68). The close association between the LMP1 induction and the EBV lytic cycle can be explained in two ways. One possibility is a coincidence that the reactivation-triggering stimuli may upregulate LMP1 expression through a pathway independent of the viral lytic cycle per se (4, 61, 66). The other reasonable yet unproven possibility is that LMP1 can be expressed as a lytic gene under the regulation of the lytic program. During EBV reactivation, the expression cascade of lytic genes is started from the induction of two immediate-early proteins, Rta and Zta (21, 57, 59). These key transcriptional activators autostimulate their own expression, reciprocally activate each other, and cooperatively induce the downstream early and late genes (1, 21, 45, 57, 59). Interestingly, the induction kinetic of full-length LMP1 is similar to that of early lytic genes in some cases of EBV reactivation (62). Therefore, we wondered if LMP1 can be upregulated by a lytic protein, especially by one of the immediate-early proteins.

In this study, we first identified a unique state where expression of full-length LMP1 is a downstream event of the spontaneous EBV reactivation in epithelial cells. In a further search of a lytic protein to induce LMP1, we found that Rta is an effective transcriptional activator of the LMP1 gene in both epithelial and B-lymphoid cells. These results reveal a new mechanism for the regulation of LMP1 expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

NA is an EBV-positive NPC cell line previously generated by in vitro infection of NPC-TW01 cells with recombinant Akata EBV (10). The EBV-infected HeLa cells (LA) and the EBV-infected 293 cells (293A) were established through a similar infection procedure with the same recombinant virus and under G418 selection (7). The 293A subclones were further isolated by single-cell cloning (7). 293-pZip cells are the EBV-negative 293 cells transfected with a plasmid expressing a G418-resistant gene (7). LCL-YA is a lymphoblastoid cell line immortalized by the same recombinant Akata EBV (10). P3HR-1, EBV-positive Akata, and EBV-negative Akata are Burkitt's lymphoma cell lines (56, 64). All the epithelial cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, while all the B-lymphoid cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium. Both of the cell cultures were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone).

Plasmids.

The pSUPER-derived plasmids expressing small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeted against Zta or green fluorescence protein (GFP) were constructed as described in a previous study (7). The Rta-expressing plasmid was generated by cloning Rta-coding sequences into the pSG5 plasmid (Stratagene). The Zta-expressing plasmid was derived from the pRc/CMV plasmid (Invitrogen). The plasmids expressing various GFP-Rta fusion proteins were constructed by cloning the Rta-coding sequences into the pEGFP-C1 plasmid (Clontech). ED-L1-Luc and TR-L1-Luc are reporter plasmids derived from the pGL2-basic plasmid (Promega) and were constructed as described in a previous study (6). ED-L1-Luc contains the proximal LMP1 promoter ED-L1 (coordinates 169929 to 169496) to drive the firefly luciferase gene, while TR-L1-Luc contains the distal LMP1 promoter TR-L1 (coordinates 170154 to 170012) to drive the same reporter gene (6). The pRL-TK (Promega) was used as an internal control plasmid expressing Renilla luciferase driven by the thymidine kinase promoter of herpes simplex virus.

DNA transfection.

Transfection of epithelial cells was performed by using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions, except that the reagent-to-DNA ratio was optimized for 293A (1.5 μl:1 μg), NA (2.5 μl:1 μg), and LA (2 μl:1 μg) cells. For suppression of spontaneous EBV reactivation by Zta-targeted siRNA, 293A cell clones were subcultured three times and repeatedly transfected with siRNA expression plasmid as described previously (7). Transfection of B-lymphoid cells was carried out by electroporation. Cells (107) were electroporated (960 μF, 200 V) with a total of 50 μg of DNA by using an Electro Cell Manipulator ECM630 (BTX).

Antibodies.

Monoclonal antibodies used for detection of EBV proteins included S12 (anti-LMP1) (48), 4F10 (anti-Zta) (69), 467 (anti-Rta), 88A9 (anti-BMRF1) (70), and PE2 (anti-EBNA2) (77). An NPC patient's serum was used for detection of EBNA1 protein (8). The anti-β-actin antibody AC-15 was purchased from Sigma, and anti-α-tubulin antibody Ab-1 was from Calbiochem.

Immunoblotting assay.

Cells were lysed in the sample buffer (3% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1.6 M urea, 4% β-mercaptoethanol). The following procedure, including polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunodetection of target proteins, was performed as described previously (8). The positive control for EBV lytic proteins was the lysate of NA cells treated with 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (40 ng/ml) and sodium n-butyrate (3 mM) for 48 h (10). The cell lysate of LCL-YA was used as the positive control of EBNA2 protein.

Northern blotting assay.

Total RNAs were extracted by using REzol C&T reagent (Bio-protech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RNAs were subjected to electrophoresis (40 μg for each lane) in a 1% agarose gel containing 6% formaldehyde. After being transferred onto an Immobilon-NY+ membrane (Millipore), the RNA blot was hybridized with 32P-labeled DNA probes of LMP1 or GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) by using a Rediprime II labeling kit (Amersham Biosciences) and ULTRAhyb hybridization buffer (Ambion). After stringent washing, the blot was exposed to an X-ray film.

RT-PCR.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed as described previously (9). Briefly, by using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), total RNAs were reverse transcribed with oligo(dT)15 as the primer. The RT products were then subjected to the subsequent PCR analysis. We used TR-F and LP-R primers for detection of LMP1 transcripts initiated specifically from TR-L1, while ED-F and LP-R primers were used to detect a common region of all transcripts initiated from TR-L1 and ED-L1 (6). Detection of cellular GAPDH was carried out as an internal control. Sequences of the PCR primers are as follows: for TR-F, CTAACACAAACACACGCTTTCTAC (coordinates 169706 to 169683); for LP-R, CCAGAGAATCTCCAAGTAGATCC (coordinates 168928 to 168950); for ED-F, CCATGGAACGCGACCTTGAGAG (coordinates 169473 to 169452); for GAPDH forward primer, GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGT; and for GAPDH reverse primer, GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC.

Reporter gene assay.

For studies of epithelial cells, a 1.5-μg reporter plasmid, a 3.5-μg effector plasmid, and a 0.5-μg pRL-TK internal control plasmid were cotransfected into 293 cells. For studies of B-lymphoid cells, 107 EBV-negative Akata cells were electroporated with 10 μg of reporter plasmid, a 35 μg of effector plasmid, and a 5 μg of control plasmid. At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were harvested and subjected to a luciferase assay with a Dual-Glo assay kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The activity of Renilla luciferase (from the internal control) was used to calibrate the activity of firefly luciferase (from the reporter). A control experiment was performed by cotransfection with the promoterless reporter (pGL2-basic) and the control vector (pSG5 or pEGFP-C1). By comparison with the control experiment, for which the activity was set to 1, the promoter activity to drive the reporter was calculated and shown as the relative luciferase activity. All the reporter gene assays were performed at least twice, and a representative result for each experiment is shown.

RESULTS

LMP1 expression is a downstream event of the spontaneous EBV reactivation in 293A cells.

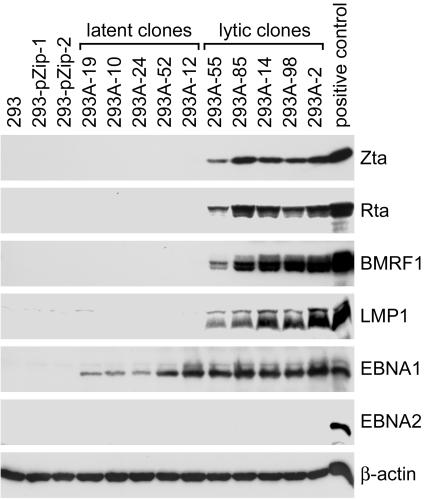

One possibility to complicate the association between LMP1 induction and EBV reactivation is that some lytic cycle-inducing agents may also upregulate LMP1 expression directly (4, 61, 66). To avoid the potential effects of those stimulating agents, we first examined LMP1 expression in cells with spontaneous EBV reactivation in the absence of exogenous stimuli. In a recent study, several stable clones of Akata EBV-infected 293 cells (293A) have been established (7). EBV infection was restricted to latency in some of the cell clones, designated “latent clones” (Fig. 1). Some other clones, designated “lytic clones,” spontaneously expressed lytic proteins such as Zta, Rta, and BMRF1 (Fig. 1) (7). By analyzing the expression profiles of viral proteins in these cell clones, we found that LMP1 expression is closely associated with the expression of the lytic antigens but not with EBNA1 or EBNA2 (Fig. 1). Only the 55-kDa full-length LMP1 protein of Akata EBV was detected in the lytic clones, consistent with a previous study showing that Akata EBV does not produce amino-terminally truncated LMP1 (68).

FIG. 1.

LMP1 expression is associated with the expression of lytic genes in 293A cells. Ten subclones of EBV-infected 293A cells were examined for the expression of EBV proteins with an immunoblotting assay. The target proteins included Zta, Rta, BMRF1, LMP1, EBNA1, and EBNA2. Detection of cellular β-actin was carried out as an internal control. Five of the cell clones showing restricted EBV latency are designated latent clones, while other five clones exhibiting spontaneous virus reactivation are designated lytic clones (7). Chemically activated NA cells were used as a positive control of the viral proteins, except that LCL-YA was used as the positive control of EBNA2. Negative controls of the viral proteins included parental 293 cells and two G418-resistant transfectants, 293-pZip-1 and 293-pZip-2 (7).

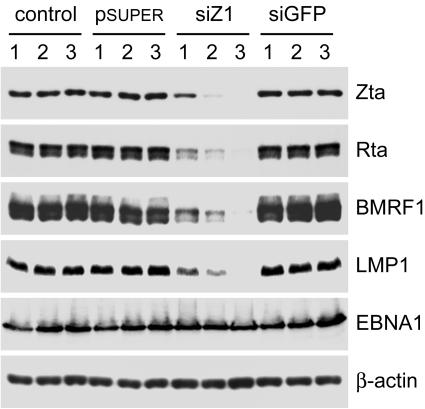

To test if LMP1 expression is a downstream event of the spontaneous EBV reactivation, we examined the result when the expression of lytic genes was inhibited by Zta-targeted siRNA, siZ1 (7). It has been previously shown that the Zta-specific RNA interference degrades not only Zta monocistronic mRNA but also endogenous Rta-Zta bicistronic mRNA, and thus, it may completely block the lytic cycle by inhibiting the expression of Zta, Rta, and perhaps all the downstream genes (7, 46). Repeated transfection with the plasmids expressing siZ1, but not an irrelevant siRNA, gradually reduced the levels of Zta, Rta, and BMRF1 in a lytic clone, 293A-2 (Fig. 2). Interestingly, LMP1 expression was also decreased significantly when expression of the lytic genes was inhibited (Fig. 2). The reduction of LMP1 is not likely attributable to siZ1-caused degradation of LMP1 RNA as an off-target event, since siZ1 had no effect on the LMP1 expression driven by a heterologous simian virus 40 promoter (data not shown). Meanwhile, expression of EBNA1 was not affected in the study (Fig. 2). Similar results were also observed in the study with another lytic clone, 293A-98 (data not shown). These data strongly suggest that the expression of LMP1 is under the control of at least one lytic gene product during spontaneous EBV reactivation in 293A lytic clones.

FIG. 2.

LMP1 expression is a downstream event of spontaneous EBV reactivation in the lytic clone 293A-2. The cells were subcultured three times, and each passage was either mock transfected (control) or transfected once with the vector plasmid pSUPER or its derivatives expressing siZ1 or an irrelevant siRNA, siGFP (7). Cells at passages 1, 2, and 3 were harvested and subjected to immunoblotting assay for detection of proteins including Zta, Rta, BMRF1, LMP1, EBNA1, and cellular β-actin.

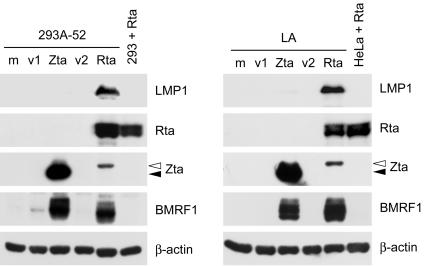

Rta induces LMP1 expression in EBV-infected epithelial cells.

Among the EBV lytic gene products, Rta and Zta are the most likely candidates to upregulate LMP1, considering their potent and essential roles in transactivation of downstream lytic genes (21, 57, 59). Therefore, we tested whether ectopic expression of Rta or Zta can induce LMP1 expression in EBV-infected epithelial cells including LA, NA, and a latent clone, 293A-52. Before plasmid transfection, EBV infection is latent and LMP1 expression is undetectable or detected at a very low level in these cells (Fig. 1 and 3) (10). Figure 3 shows that exogenous Rta and Zta induced expression of BMRF1 at a comparable level, indicating that both of the transactivators are functional in 293A-52 and LA cells. Interestingly, expression of LMP1 protein was prominently induced only by exogenous Rta but not Zta (Fig. 3). Similar results were also obtained from the study by using NA cells (data not shown). Meanwhile, ectopic expression of Rta did not induce EBNA2 in these cells (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

LMP1 is induced by ectopic expression of Rta in EBV-infected epithelial cells. 293A-52 or LA cells were mock transfected (m) or transfected with plasmids expressing Zta or Rta for 48 h and then subjected to the immunoblotting assay for detection of the indicated proteins. The plasmid pRc/CMV (v1) and pSG5 (v2) are the control vectors for Zta- and Rta-expressing plasmids, respectively. For a negative control of Rta-induced viral proteins, we used the parental EBV-negative cells (293 or HeLa) transfected with Rta-expressing plasmids. There is a difference in protein molecular weight between the exogenous Zta of the B95-8 strain (indicated by closed arrowheads) and the endogenous Zta of the Akata strain (indicated by open arrowheads).

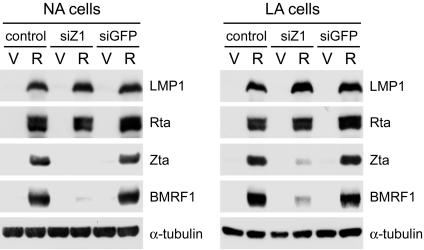

It should be noticed that in 293A-52 and LA cells, exogenous Rta induced the expression of endogenous Zta, but exogenous Zta did not induce endogenous Rta at a detectable level (Fig. 3). It is possible that the Rta-mediated induction of LMP1 is the result of the cooperation of Rta and Zta, which has been shown to upregulate some other genes (21, 45, 59). To elucidate the role of Zta in Rta-induced LMP1 expression, we used siZ1 to knock down Zta in the study (7). Rta-induced expression of Zta was significantly diminished by siZ1, while exogenous Rta itself was not affected (Fig. 4). The Rta-mediated upregulation of BMRF1 was inhibited by expression of siZ1, indicating that the induction of BMRF1 is essentially dependent on Zta (Fig. 4) (7, 21). By contrast, Rta-induced LMP1 expression was sustained even though the levels of Zta and BMRF1 were largely reduced (Fig. 4). Therefore, the Rta-mediated induction of LMP1 is dependent on neither Zta nor BMRF1.

FIG. 4.

Rta-induced LMP1 expression is independent of Zta and BMRF1. NA or LA cells were mock transfected (control) or transfected with plasmids expressing siZ1 or siGFP for 48 h, followed by posttransfection with control vectors (V) or Rta-expressing plasmids (R) for 24 h. The immunoblotting assay was performed to detect the expression of indicated proteins.

Rta induces LMP1 expression at a transcriptional level.

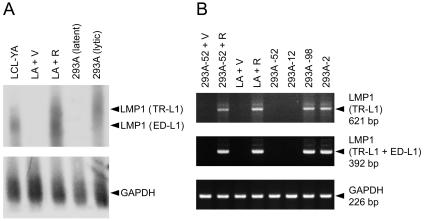

Next, we examined whether Rta upregulates LMP1 at the RNA level. As has been mentioned above, transcription of the full-length LMP1 gene can be initiated from two promoters. Transcripts initiated from the proximal promoter ED-L1 are about 2.8 kb, and those from the distal promoter TR-L1 are about 3.5 kb (6, 11, 63). The Northern blotting assay revealed that both the ED-L1- and TR-L1-driven LMP1 transcripts were significantly increased by Rta in LA cells (Fig. 5A). The LMP1 transcripts initiated from TR-L1 were more than those from ED-L1 in 293A lytic clones, while LMP1 RNA was not detectable in 293A latent clones (Fig. 5A). RT-PCR analysis further confirmed that Rta prominently induced TR-L1-initiated and total LMP1 RNAs in 293A-52 and LA cells (Fig. 5B), revealing that Rta-mediated induction of LMP1 occurs at the RNA level.

FIG. 5.

Rta increases LMP1 transcripts in EBV-infected epithelial cells. (A) Detection of LMP1 transcripts by the Northern blotting assay. In the assay, we examined LA cells transfected with control vectors (V) or Rta-expressing plasmids (R), pooled 293A latent clones, and pooled 293A lytic clones. Total RNAs were subjected to the assay and hybridized with 32P-labeled DNA probes of LMP1 or the internal control GAPDH. The predicted LMP1 transcripts initiated from ED-L1 are about 2.8 kb, and those from TR-L1 are about 3.5 kb (6, 63). LCL-YA was used for a reference of ED-L1-initiated LMP1 transcripts. (B) RT-PCR analysis of LMP1 transcripts. In the assay, we examined LA and 293A-52 cells transfected with control vectors (V) or Rta-expressing plasmids (R), two 293A latent clones (293A-52 and 293A-12), and two 293A lytic clones (293A-98 and 293A-2). Different primer sets were used to detect LMP1 transcripts initiated specifically from TR-L1 or total transcripts from TR-L1 and ED-L1. The expected sizes of PCR products are indicated.

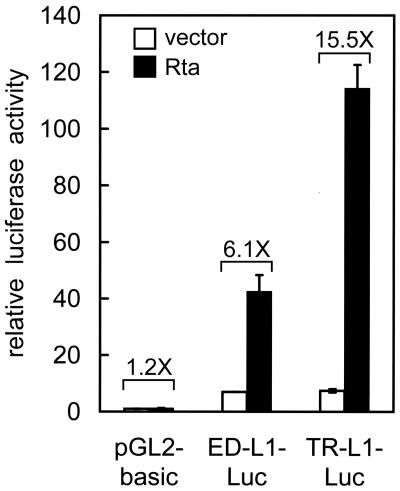

Thus far, we have performed the study with EBV-positive cells, so it still cannot be ruled out that Rta may upregulate LMP1 expression indirectly through other viral gene products. To examine whether Rta can activate the LMP1 promoters in an EBV-negative cell background, a reporter gene assay was carried out with 293 cells. Consistent with previous studies, both ED-L1 and TR-L1 had basal promoter activities in EBV-negative epithelial cells (Fig. 6) (6, 12, 20). Expression of Rta considerably stimulated the activities of both promoters ED-L1 (6.1-fold) and, to a higher extent, TR-L1 (15.5-fold) (Fig. 6). On the other hand, expression of Zta or EBNA2 had no effect on the activities of LMP1 promoters in this assay (data not shown). This result demonstrates that Rta can exert its transactivation effect on the LMP1 promoters independently of other EBV gene products.

FIG. 6.

Rta activates both LMP1 promoters in EBV-negative epithelial cells. 293 cells were transfected with indicated reporter plasmids in conjunction with either control vectors or plasmids expressing Rta. At 48 h posttransfection, the luciferase assay was performed. The promoter activity was calculated and shown as the relative luciferase activity as described in Materials and Methods. The experiment was carried out in duplicate, and error bars are shown. The Rta-induced activation (n-fold) for each reporter is also indicated.

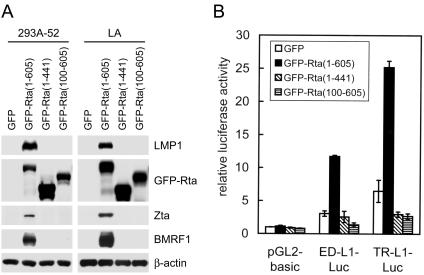

Both the amino and carboxyl termini of Rta are required for the induction of LMP1.

It has been previously shown that both DNA-binding and dimerization domains of the Rta protein are located at the amino-terminal region and that the carboxyl-terminal region of Rta contains a potent transactivation domain (27, 47). To identify the essential regions of Rta for induction of LMP1, we generated plasmids expressing GFP-Rta fusion proteins with the full-length (containing amino acids 1 to 605), carboxyl-terminally truncated (containing amino acids 1 to 441), or amino-terminally truncated (containing amino acids 100 to 605) form of Rta. Like the original Rta protein, all the fusion proteins showed nuclear localization when they were expressed in cells (data not shown). Full-length GFP-Rta induced expression of LMP1, Zta, and BMRF1 in 293A-52 and LA cells (Fig. 7A). Truncation of either the amino- or the carboxyl-terminal region of Rta abolished the ability to induce the three EBV genes (Fig. 7A). A reporter gene assay further confirmed that both of the truncated forms of Rta fusion proteins failed to activate the LMP1 promoters (Fig. 7B). Therefore, both the amino and carboxyl termini of Rta are essential for the induction of LMP1.

FIG. 7.

Both the amino and carboxyl termini of Rta are required for the induction of LMP1. (A) 293A-52 and LA cells were transfected with plasmids expressing GFP or GFP-Rta fusion proteins with full-length (amino acids 1 to 605), carboxyl-terminally truncated (amino acids 1 to 441), or amino-terminally truncated (amino acids 100 to 605) Rta. After 48 h, the cells were harvested for the immunoblotting assay to detect the indicated proteins. (B) 293 cells were transfected with indicated reporter plasmids in conjunction with one of the plasmids expressing GFP or various GFP-Rta fusion proteins. The reporter gene assay was performed at 48 h posttransfection and analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 6.

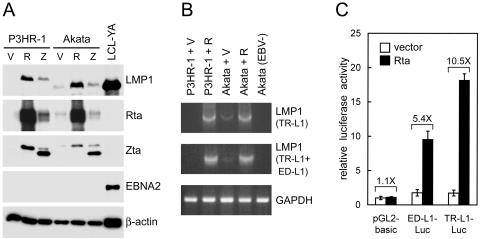

Rta induces LMP1 expression in B-lymphoid cells.

Considering that some mechanisms to regulate LMP1 expression are cell type specific, we examined whether Rta-mediated induction of LMP1 occurs in another cell type, the B-lymphoid cell. Two EBV-positive Burkitt's lymphoma cell lines, P3HR-1 and Akata, express little or no LMP1 during virus latency (62, 73). As has been observed in epithelial cells (Fig. 3 and 5), ectopic expression of Rta caused significant induction of LMP1 at both protein and RNA levels in the two B-cell lines (Fig. 8A and B). Ectopic expression of Zta slightly increased LMP1 expression, which may be attributable to the endogenous Rta that was induced by Zta (Fig. 8A). Since the EBNA2 gene is deleted in the P3HR-1 EBV genome and induction of EBNA2 was not detected in Akata cells, the Rta-induced LMP1 expression is independent of EBNA2 (Fig. 8A) (56). Furthermore, Rta activated both ED-L1 and TR-L1 in a reporter gene assay using EBV-negative Akata cells (Fig. 8C), consistent with the study of epithelial cells (Fig. 6). Accordingly, we conclude that Rta is an effective transcriptional activator of the LMP1 gene in both epithelial and B-lymphoid cells.

FIG. 8.

Rta-mediated induction of LMP1 also occurs in B-lymphoid cells. (A) P3HR-1 and Akata cells were electroporated with control vectors (V) or plasmids expressing Rta (R) or Zta (Z). After 48 h, the cells were harvested for the immunoblotting assay to detect the indicated proteins. LCL-YA was used as a positive control of LMP1 and EBNA2. The full-length LMP1 proteins of P3HR-1 EBV and Akata EBV are different in molecular weight (66, 68). The difference in sizes among the exogenous Zta and endogenous Zta of P3HR-1 and Akata EBV is also noted. (B) RT-PCR analysis of LMP1 transcripts in P3HR-1 and Akata cells transfected with either control vectors (V) or Rta-expressing plasmids (R). The EBV-negative Akata cells were used as a negative control. (C) EBV-negative Akata cells were transfected with indicated reporter plasmids in conjunction with either control vectors or Rta-expressing plasmids. The reporter gene assay was performed at 48 h posttransfection and presented as described in the legend to Fig. 6.

DISCUSSION

In summary, this study examined a possible mechanism to upregulate LMP1 in the EBV lytic cycle. First, we identified that LMP1 expression is a downstream event of the spontaneous EBV reactivation in 293A cells. We also clearly demonstrated that Rta functions as an effective transcriptional activator of the LMP1 gene in both epithelial and B-lymphoid cells. This study reveals a new mechanism by which LMP1 can be induced by a lytic transactivator, expanding the knowledge of LMP1 regulation in the EBV life cycle.

Although the close association between induction of LMP1 and EBV reactivation has been observed in previous studies, little was known about how LMP1 expression is regulated in the lytic stage (4, 10, 13, 62, 66, 68). Whether any EBV lytic protein is involved in the upregulation of LMP1 had not been tested. One possibility to make this issue complicated is that some lytic cycle-inducing agents may also stimulate LMP1 expression directly. For example, DNA methylation and histone deacetylation negatively regulate the promoters of LMP1 and Zta, so the DNA demethylating agents or histone deacetylase inhibitors may activate both LMP1 expression and EBV reactivation simultaneously but perhaps separately (3, 32, 50, 66). To avoid the potential effects of the exogenous stimuli, we started the study from an examination of spontaneous EBV reactivation, with which LMP1 expression is also closely associated (Fig. 1). Interestingly, the expression of LMP1 was reduced significantly when the expression cascade of lytic genes was inhibited by Zta-targeted siRNA, suggesting that LMP1 expression is under the control of at least one lytic gene product during spontaneous EBV reactivation in 293A lytic clones (Fig. 2). Since the Zta-targeted RNA interference blocked the expression of all lytic genes examined, we were unable to identify which lytic gene product is responsible for LMP1 expression in this experiment (7). Through another approach, we searched for a lytic protein to induce LMP1 by ectopic expression of the individual lytic gene, and we found that Rta is the lytic protein (Fig. 3).

A series of experiments pointed toward Rta as being sufficient to upregulate LMP1 expression independently of other EBV proteins. First, induction of LMP1 by exogenous Rta was not affected when endogenous Zta was knocked down, indicating that Rta does not require the cooperation with Zta for LMP1 induction (Fig. 4). Rta-induced LMP1 expression is not dependent on EBNA2 either, since EBNA2 was not induced by exogenous Rta and Rta still upregulated LMP1 expression in cells infected with an EBNA2-deleted EBV (Fig. 8A and data not shown). Furthermore, reporter gene assays demonstrated that Rta can activate the LMP1 promoters in EBV-negative cells (Fig. 6 and 8C). This study, however, cannot rule out that Rta-mediated LMP1 induction may be augmented by another EBV protein(s), nor can we exclude the possibility that in addition to Rta, another EBV lytic protein(s) may upregulate LMP1.

The LMP1 induction mediated by Rta is quite different from that mediated by EBNA2. EBNA2 stimulates only ED-L1, and the induction occurs in B cells but not in T cells or epithelial cells (20, 33, 73). This observation indicates that ED-L1, but not TR-L1, contains cis elements for the responsiveness and that the EBNA2-mediated transactivation requires a certain cellular factor(s) restricted to the specific cell type (20, 33). By contrast, Rta activates both ED-L1 and TR-L1, and the transactivation is observed in both B cells and epithelial cells (Fig. 5, 6, and 8). We propose that LMP1 expression is regulated by different viral proteins in different states of EBV infection. In EBV-immortalized B cells, the infection is latent and LMP1 expression is induced by EBNA2 and may be enhanced by EBNA-LP, EBNA-3C, or EBNA1 (23, 33, 54, 78). On the other hand, Rta can upregulate LMP1 effectively when the lytic cycle is triggered in various cells, especially in those cells that express little or no LMP1 during EBV latency (62).

There is still a question as to how Rta exerts the activation effect on the LMP1 promoters. It has been noted that Rta can stimulate gene transcription through multiple mechanisms. Rta is able to bind directly to some promoters of its target genes, including BMLF1, BMRF1, and BALF2 (25, 30, 55). Although Rta prefers binding to a GC-rich motif, the DNA sequences of the Rta-binding sites, however, are very diverse and somewhat unpredictable (25, 26, 30). Alternatively, Rta can upregulate gene expression through various indirect mechanisms that do not involve direct DNA binding. For example, Rta activates the Zta promoter through a pathway that requires signaling of MAPK/JNK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt, activates the promoter of EBV DNA polymerase gene through USF and E2F, and autostimulates its own promoter through Sp1/Sp3 binding sites (1, 14, 43, 58). So far, we have identified that both the amino and carboxyl termini of Rta are essential for the induction of LMP1, consistent with previous studies showing the importance of these two regions for Rta-mediated transactivation (Fig. 7) (27, 47). Our preliminary study suggested that several distinct elements in the LMP1 promoters may contribute to the Rta responsiveness (our unpublished data). It is our goal to clarify how Rta activates the LMP1 promoters, what cellular factors are involved, and whether ED-L1 and TR-L1 are activated through the same mechanism.

It is intriguing to consider LMP1 a lytic gene. When the infected cells express little or even no LMP1 in EBV latency, significant induction of LMP1 during virus reactivation should agree with this notion (62). In addition, our study shows that LMP1 can be upregulated by the immediate-early protein Rta, further fitting LMP1 expression into the regulatory cascade of the lytic cycle. There is a notable clue from Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), another human gammaherpesvirus. At a position equivalent to that of the LMP1 gene in the viral genome, KSHV encodes a distinct membrane protein, K1 (38). Although LMP1 and K1 proteins share no amino acid similarity, they do have similar functions in signaling transduction, antiapoptosis, and cell transformation (41, 52, 67). Interestingly, K1 is expressed as a lytic gene, and its promoter can be activated by an immediate-early protein, ORF50, the KSHV homologue of EBV Rta (5, 38). Therefore, induction of LMP1 (or its functional analogue) by Rta (or its homologue) during virus reactivation is likely to be a conserved event for gammaherpesviruses. This raises a question: what are the roles of the transforming membrane proteins in the virus lytic cycle? As has been suggested, LMP1 and K1 may prepare a suitable cell environment for virus replication by promoting cell survival or by triggering some essential signaling pathways (39, 67, 74). On the other hand, they may negatively modulate the lytic cycle, since ectopic expression of LMP1 or K1 inhibits the virus reactivation (2, 40). Another observation implies that concurrent expression of LMP1 and other lytic proteins may contribute to the pathogenesis of oral hairy leukoplakia, an epithelial lesion with permissive EBV infection (74). The whole picture of LMP1's functions in the lytic cycle remains to be elucidated.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Council (grants NSC 92-3112-B-002-014, NSC 92-2320-B-002-167, NSC 93-3112-B-002-006, and NSC 93-2320-B-002-025). Yao Chang was a recipient of an NHRI postdoctoral fellowship award (RE90N003) during June 2001 to May 2003.

The skillful technical assistance of Chin-Min Ho and Pei-Ru Lwo is appreciated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamson, A. L., D. Darr, E. Holley-Guthrie, R. A. Johnson, A. Mauser, J. Swenson, and S. Kenney. 2000. Epstein-Barr virus immediate-early proteins BZLF1 and BRLF1 activate the ATF2 transcription factor by increasing the levels of phosphorylated p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinases. J. Virol. 74:1224-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler, B., E. Schaadt, B. Kempkes, U. Zimber-Strobl, B. Baier, and G. W. Bornkamm. 2002. Control of Epstein-Barr virus reactivation by activated CD40 and viral latent membrane protein 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:437-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Sasson, S. A., and G. Klein. 1981. Activation of the Epstein-Barr virus genome by 5-aza-cytidine in latently infected human lymphoid lines. Int. J. Cancer 28:131-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boos, H., R. Berger, C. Kuklik-Roos, T. Iftner, and N. Mueller-Lantzsch. 1987. Enhancement of Epstein-Barr virus membrane protein (LMP) expression by serum, TPA, or n-butyrate in latently infected Raji cells. Virology 159:161-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowser, B. S., S. M. DeWire, and B. Damania. 2002. Transcriptional regulation of the K1 gene product of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 76:12574-12583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang, M. H., C. K. Ng, Y. J. Lin, C. L. Liang, P. J. Chung, M. L. Chen, Y. S. Tyan, C. Y. Hsu, C. H. Shu, and Y. S. Chang. 1997. Identification of a promoter for the latent membrane protein 1 gene of Epstein-Barr virus that is specifically activated in human epithelial cells. DNA Cell Biol. 16:829-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, Y., S. S. Chang, H. H. Lee, S. L. Doong, K. Takada, and C. H. Tsai. 2004. Inhibition of the Epstein-Barr virus lytic cycle by Zta-targeted RNA interference. J. Gen. Virol. 85:1371-1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang, Y., S. D. Cheng, and C. H. Tsai. 2002. Chromosomal integration of Epstein-Barr virus genomes in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Head Neck 24:143-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang, Y., T. S. Sheen, J. Lu, Y. T. Huang, J. Y. Chen, C. S. Yang, and C. H. Tsai. 1998. Detection of transcripts initiated from two viral promoters (Cp and Wp) in Epstein-Barr virus-infected nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells and biopsies. Lab. Investig. 78:715-726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang, Y., C. H. Tung, Y. T. Huang, J. Lu, J. Y. Chen, and C. H. Tsai. 1999. Requirement for cell-to-cell contact in Epstein-Barr virus infection of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells and keratinocytes. J. Virol. 73:8857-8866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, H., J. M. Lee, Y. Zong, M. Borowitz, M. H. Ng, R. F. Ambinder, and S. D. Hayward. 2001. Linkage between STAT regulation and Epstein-Barr virus gene expression in tumors. J. Virol. 75:2929-2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, M. L., R. C. Wu, S. T. Liu, and Y. S. Chang. 1995. Characterization of 5′-upstream sequence of the latent membrane protein 1 (LMP-1) gene of an Epstein-Barr virus identified in nasopharyngeal carcinoma tissues. Virus Res. 37:75-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Contreras-Salazar, B., B. Ehlin-Henriksson, G. Klein, and M. G. Masucci. 1990. Up regulation of the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-encoded membrane protein LMP in the Burkitt's lymphoma line Daudi after exposure to n-butyrate and after EBV superinfection. J. Virol. 64:5441-5447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darr, C. D., A. Mauser, and S. Kenney. 2001. Epstein-Barr virus immediate-early protein BRLF1 induces the lytic form of viral replication through a mechanism involving phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase activation. J. Virol. 75:6135-6142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawson, C. W., G. Tramountanis, A. G. Eliopoulos, and L. S. Young. 2003. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway to promote cell survival and induce actin filament remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 278:3694-3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eliopoulos, A. G., J. H. Caamano, J. Flavell, G. M. Reynolds, P. G. Murray, J. L. Poyet, and L. S. Young. 2003. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent infection membrane protein 1 regulates the processing of p100 NF-κB2 to p52 via an IKKγ/NEMO-independent signalling pathway. Oncogene 22:7557-7569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eliopoulos, A. G., N. J. Gallagher, S. M. Blake, C. W. Dawson, and L. S. Young. 1999. Activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein 1 coregulates interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 production. J. Biol. Chem. 274:16085-16096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eliopoulos, A. G., and L. S. Young. 1998. Activation of the cJun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway by the Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1). Oncogene 16:1731-1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erickson, K. D., C. Berger, W. F. Coffin III, E. Schiff, D. M. Walling, and J. M. Martin. 2003. Unexpected absence of the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) lyLMP-1 open reading frame in tumor virus isolates: lack of correlation between Met129 status and EBV strain identity. J. Virol. 77:4415-4422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fahraeus, R., A. Jansson, A. Sjoblom, T. Nilsson, G. Klein, and L. Rymo. 1993. Cell phenotype-dependent control of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 gene regulatory sequences. Virology 195:71-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feederle, R., M. Kost, M. Baumann, A. Janz, E. Drouet, W. Hammerschmidt, and H. J. Delecluse. 2000. The Epstein-Barr virus lytic program is controlled by the co-operative functions of two transactivators. EMBO J. 19:3080-3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fries, K. L., W. E. Miller, and N. Raab-Traub. 1996. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 blocks p53-mediated apoptosis through the induction of the A20 gene. J. Virol. 70:8653-8659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gahn, T. A., and B. Sugden. 1995. An EBNA-1-dependent enhancer acts from a distance of 10 kilobase pairs to increase expression of the Epstein-Barr virus LMP gene. J. Virol. 69:2633-2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gires, O., F. Kohlhuber, E. Kilger, M. Baumann, A. Kieser, C. Kaiser, R. Zeidler, B. Scheffer, M. Ueffing, and W. Hammerschmidt. 1999. Latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus interacts with JAK3 and activates STAT proteins. EMBO J. 18:3064-3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gruffat, H., N. Duran, M. Buisson, F. Wild, R. Buckland, and A. Sergeant. 1992. Characterization of an R-binding site mediating the R-induced activation of the Epstein-Barr virus BMLF1 promoter. J. Virol. 66:46-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gruffat, H., and A. Sergeant. 1994. Characterization of the DNA-binding site repertoire for the Epstein-Barr virus transcription factor R. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:1172-1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hardwick, J. M., L. Tse, N. Applegren, J. Nicholas, and M. A. Veliuona. 1992. The Epstein-Barr virus R transactivator (Rta) contains a complex, potent activation domain with properties different from those of VP16. J. Virol. 66:5500-5508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofelmayr, H., L. J. Strobl, C. Stein, G. Laux, G. Marschall, G. W. Bornkamm, and U. Zimber-Strobl. 1999. Activated mouse Notch1 transactivates Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2-regulated viral promoters. J. Virol. 73:2770-2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hudson, G. S., P. J. Farrell, and B. G. Barrell. 1985. Two related but differentially expressed potential membrane proteins encoded by the EcoRI Dhet region of Epstein-Barr virus B95-8. J. Virol. 53:528-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hung, C. H., and S. T. Liu. 1999. Characterization of the Epstein-Barr virus BALF2 promoter. J. Gen. Virol. 80:2747-2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imai, S., J. Nishikawa, and K. Takada. 1998. Cell-to-cell contact as an efficient mode of Epstein-Barr virus infection of diverse human epithelial cells. J. Virol. 72:4371-4378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jenkins, P. J., U. K. Binne, and P. J. Farrell. 2000. Histone acetylation and reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus from latency. J. Virol. 74:710-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johannsen, E., E. Koh, G. Mosialos, X. Tong, E. Kieff, and S. R. Grossman. 1995. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 transactivation of the latent membrane protein 1 promoter is mediated by Jκ and PU.1. J. Virol. 69:253-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaye, K. M., K. M. Izumi, and E. Kieff. 1993. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 is essential for B-lymphocyte growth transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:9150-9154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kieff, E., and A. B. Rickinson. 2001. Epstein-Barr virus and its replication, p. 2511-2573. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 36.Kim, K. R., T. Yoshizaki, H. Miyamori, K. Hasegawa, T. Horikawa, M. Furukawa, S. Harada, M. Seiki, and H. Sato. 2000. Transformation of Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) induces expression of Ets1 and invasive growth. Oncogene 19:1764-1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kulwichit, W., R. H. Edwards, E. M. Davenport, J. F. Baskar, V. Godfrey, and N. Raab-Traub. 1998. Expression of the Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces B cell lymphoma in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:11963-11968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lagunoff, M., and D. Ganem. 1997. The structure and coding organization of the genomic termini of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Virology 236:147-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lagunoff, M., D. M. Lukac, and D. Ganem. 2001. Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif-dependent signaling by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K1 protein: effects on lytic viral replication. J. Virol. 75:5891-5898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee, B.-S., M. Paulose-Murphy, Y.-H. Chung, M. Connlole, S. Zeichner, and J. U. Jung. 2002. Suppression of tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate-induced lytic reactivation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus by K1 signal transduction. J. Virol. 76:12185-12199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee, H., R. Veazey, K. Williams, M. Li, J. Guo, F. Neipel, B. Fleckenstein, A. Lackner, R. C. Desrosiers, and J. U. Jung. 1998. Deregulation of cell growth by the K1 gene of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Nat. Med. 4:435-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li, H. P., and Y. S. Chang. 2003. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1: structure and functions. J. Biomed. Sci. 10:490-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu, C., N. D. Sista, and J. S. Pagano. 1996. Activation of the Epstein-Barr virus DNA polymerase promoter by the BRLF1 immediate-early protein is mediated through USF and E2F. J. Virol. 70:2545-2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu, M. T., Y. R. Chen, S. C. Chen, C. Y. Hu, C. S. Lin, Y. T. Chang, W. B. Wang, and J. Y. Chen. 2004. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces micronucleus formation, represses DNA repair and enhances sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents in human epithelial cells. Oncogene 23:2531-2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu, P., and S. H. Speck. 2003. Synergistic autoactivation of the Epstein-Barr virus immediate-early BRLF1 promoter by Rta and Zta. Virology 310:199-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manet, E., H. Gruffat, M. C. Trescol-Biemont, N. Moreno, P. Chambard, J. F. Giot, and A. Sergeant. 1989. Epstein-Barr virus bicistronic mRNAs generated by facultative splicing code for two transcriptional trans-activators. EMBO J. 8:1819-1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manet, E., A. Rigolet, H. Gruffat, J. F. Giot, and A. Sergeant. 1991. Domains of the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) transcription factor R required for dimerization, DNA binding and activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:2661-2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mann, K. P., D. Staunton, and D. A. Thorley-Lawson. 1985. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded protein found in plasma membranes of transformed cells. J. Virol. 55:710-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller, W. E., H. S. Earp, and N. Raab-Traub. 1995. The Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Virol. 69:4390-4398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Minarovits, J., L. F. Hu, S. Minarovits-Kormuta, G. Klein, and I. Ernberg. 1994. Sequence-specific methylation inhibits the activity of the Epstein-Barr virus LMP 1 and BCR2 enhancer-promoter regions. Virology 200:661-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murono, S., H. Inoue, T. Tanabe, I. Joab, T. Yoshizaki, M. Furukawa, and J. S. Pagano. 2001. Induction of cyclooxygenase-2 by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 is involved in vascular endothelial growth factor production in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:6905-6910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nicholas, J. 2003. Human herpesvirus-8-encoded signalling ligands and receptors. J. Biomed. Sci. 10:475-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ning, S., A. M. Hahn, L. E. Huye, and J. S. Pagano. 2003. Interferon regulatory factor 7 regulates expression of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1: a regulatory circuit. J. Virol. 77:9359-9368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nitsche, F., A. Bell, and A. Rickinson. 1997. Epstein-Barr virus leader protein enhances EBNA-2-mediated transactivation of latent membrane protein 1 expression: a role for the W1W2 repeat domain. J. Virol. 71:6619-6628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Quinlivan, E. B., E. A. Holley-Guthrie, M. Norris, D. Gutsch, S. L. Bachenheimer, and S. C. Kenney. 1993. Direct BRLF1 binding is required for cooperative BZLF1/BRLF1 activation of the Epstein-Barr virus early promoter, BMRF1. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:1999-2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rabson, M., L. Gradoville, L. Heston, and G. Miller. 1982. Non-immortalizing P3J-HR-1 Epstein-Barr virus: a deletion mutant of its transforming parent, Jijoye. J. Virol. 44:834-844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ragoczy, T., L. Heston, and G. Miller. 1998. The Epstein-Barr virus Rta protein activates lytic cycle genes and can disrupt latency in B lymphocytes. J. Virol. 72:7978-7984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ragoczy, T., and G. Miller. 2001. Autostimulation of the Epstein-Barr virus BRLF1 promoter is mediated through consensus Sp1 and Sp3 binding sites. J. Virol. 75:5240-5251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ragoczy, T., and G. Miller. 1999. Role of the Epstein-Barr virus RTA protein in activation of distinct classes of viral lytic cycle genes. J. Virol. 73:9858-9866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rickinson, A. B., and E. Kieff. 2001. Epstein-Barr virus, p. 2575-2627. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 61.Rowe, M., H. S. Evans, L. S. Young, K. Hennessy, E. Kieff, and A. B. Rickinson. 1987. Monoclonal antibodies to the latent membrane protein of Epstein-Barr virus reveal heterogeneity of the protein and inducible expression in virus-transformed cells. J. Gen. Virol. 68:1575-1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rowe, M., A. L. Lear, D. Croom-Carter, A. H. Davies, and A. B. Rickinson. 1992. Three pathways of Epstein-Barr virus gene activation from EBNA1-positive latency in B lymphocytes. J. Virol. 66:122-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sadler, R. H., and N. Raab-Traub. 1995. The Epstein-Barr virus 3.5-kilobase latent membrane protein 1 mRNA initiates from a TATA-less promoter within the first terminal repeat. J. Virol. 69:4577-4581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shimizu, N., A. Tanabe-Tochikura, Y. Kuroiwa, and K. Takada. 1994. Isolation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-negative cell clones from the EBV-positive Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) line Akata: malignant phenotypes of BL cells are dependent on EBV. J. Virol. 68:6069-6073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sjoblom, A., W. Yang, L. Palmqvist, A. Jansson, and L. Rymo. 1998. An ATF/CRE element mediates both EBNA2-dependent and EBNA2-independent activation of the Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 gene promoter. J. Virol. 72:1365-1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sjoblom-Hallen, A., W. Yang, A. Jansson, and L. Rymo. 1999. Silencing of the Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 gene by the Max-Mad1-mSin3A modulator of chromatin structure. J. Virol. 73:2983-2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tomlinson, C. C., and B. Damania. 2004. The K1 protein of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus activates the Akt signaling pathway. J. Virol. 78:1918-1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Torii, T., K. Konishi, J. Sample, and K. Takada. 1998. The truncated form of the Epstein-Barr virus LMP-1 is dispensable or complimentable by the full-length form in virus infection and replication. Virology 251:273-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tsai, C. H., M. T. Liu, M. R. Chen, J. Lu, H. L. Yang, J. Y. Chen, and C. S. Yang. 1997. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies to the Zta and DNase proteins of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Biomed. Sci. 4:69-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tsai, C. H. A., M. V. Williams, and R. Glaser. 1991. Characterization of two monoclonal antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus diffuse early antigen which react to two different epitopes and have different biological function. J. Virol. Methods 33:47-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsai, C. N., C. M. Lee, C. K. Chien, S. C. Kuo, and Y. S. Chang. 1999. Additive effect of Sp1 and Sp3 in regulation of the ED-L1E promoter of the EBV LMP 1 gene in human epithelial cells. Virology 261:288-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang, D., D. Liebowitz, and E. Kieff. 1985. An EBV membrane protein expressed in immortalized lymphocytes transforms established rodent cells. Cell 43:831-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang, F., S. F. Tsang, M. G. Kurilla, J. I. Cohen, and E. Kieff. 1990. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 transactivates latent membrane protein LMP1. J. Virol. 64:3407-3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Webster-Cyriaque, J., J. Middeldorp, and N. Raab-Traub. 2000. Hairy leukoplakia: an unusual combination of transforming and permissive Epstein-Barr virus infections. J. Virol. 74:7610-7618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wilson, J. B., W. Weinberg, R. Johnson, S. Yuspa, and A. J. Levine. 1990. Expression of the BNLF-1 oncogene of Epstein-Barr virus in the skin of transgenic mice induces hyperplasia and aberrant expression of keratin 6. Cell 61:1315-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yoshizaki, T., H. Sato, M. Furukawa, and J. S. Pagano. 1998. The expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 is enhanced by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3621-3626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Young, L., C. Alfieri, K. Hennessy, H. Evans, C. O'Hara, K. C. Anderson, J. Ritz, R. S. Shapiro, A. Rickinson, E. Kieff, et al. 1989. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus transformation-associated genes in tissues of patients with EBV lymphoproliferative disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 321:1080-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhao, B., and C. E. Sample. 2000. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C activates the latent membrane protein 1 promoter in the presence of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 through sequences encompassing an Spi-1/Spi-B binding site. J. Virol. 74:5151-5160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]