Abstract

Airway diseases affect over 7% of the U.S. population and millions of patients worldwide. Asthmatic patients have wide variation in clinical severity with different clinical and physiologic manifestations of disease that may be driven by distinct biologic mechanisms. Further, the immunologic underpinnings of this complex trait disease are heterogeneous and treatment success depends on defining subgroups of asthmatics. Due to the limited availability and number of cells from the lung, the active site, in-depth investigation has been challenging. Recent advances in technology support transcriptional analysis of cells from induced sputum. Flow cytometry studies have described cells present in the sputum but a detailed analysis of these subsets is lacking. Mass cytometry or CyTOF (Cytometry by Time-Of-Flight) offers tremendous opportunities for multiparameter single cell analysis. Experiments can now allow detection of up to ~40 markers to facilitate unprecedented multidimensional cellular analyses. Here we demonstrate the use of CyTOF on primary airway samples obtained from well-characterized patients with asthma and cystic fibrosis. Using this technology, we quantify cellular frequency and functional status of defined cell subsets. Our studies provide a blueprint to define the heterogeneity among subjects and underscore the power of this single cell method to characterize airway immune status.

Keywords: sputum, immune response, eosinophil, neutrophils, lung disease, asthma, cystic fibrosis, mass cytometry, CyTOF

Introduction

Asthma affects approximately 7% of the U.S. population and millions of patients worldwide (1). The current paradigm of asthma pathogenesis proposes that defects in immunity result in persistent or chronic airway inflammation characterized by excessive mucus production, airway hyper-responsiveness, obstructive lung function, episodic wheezing, and shortness of breath (2). Asthmatic patients have wide variation in clinical severity and while current medications are effective for many, some very severely affected patients remain unresponsive to available therapeutics. Asthma research efforts have moved to defining subgroups of patients with different clinical and physiologic manifestations of disease that may be driven by distinct biologic mechanisms or relative differences in the expression of known pathways (3–5). Recent advances in technology support transcriptional analysis of cells from induced sputum (6,7) and we have recently profiled the gene expression in induced sputum of cells from asthmatic subjects to identify 3 transcriptomic endotypes of asthma (TEA) that correlate with phenotypes of disease (7).

Similar to asthma, Cystic Fibrosis (CF) is characterized by airflow obstruction and chronic airway inflammation due to impaired mucociliary clearance (8–10). CF leads to the accumulation of mucus and neutrophil-predominant debris in the airway and sputum and a different airway microenvironment due to ion transport defects (11). CF is the most common fatal genetic disease in the United States (12).

Infiltrating immune cells in the sputum are largely granulocytic and monocytic in origin, which have been characterized morphologically (3,13,14) and by flow cytometry studies (15–19). The excessive infiltration of neutrophils, eosinophils, and Th2 cells is mediated by cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 that promote IgE switching, mast cell recruitment, mucus production and airway hyper-responsiveness (2,14,20–23). Notably, severe asthma is associated with elevated numbers of eosinophils in sputum but these cells have been challenging to investigate due to the limited accessibility and number of cells generated by non-invasive delivery of hypertonic saline. Since disease severity likely correlates with a profile of functionally activated immune cells (14), the immunologic underpinnings of this complex trait disease are heterogeneous and require a detailed analysis of cellular subsets in the sputum.

The recent introduction of Mass cytometry or CyTOF (Cytometry by Time-Of-Flight) offers tremendous opportunities for multiparameter single cell analysis. CyTOF uses heavy metal ions as antibody labels and thus overcomes many of the limitations of fluorescence-based flow cytometry such as background and overlapping channels (24). Experiments can now allow detection of up to ~40 markers from each sample to facilitate unprecedented multidimensional cellular analyses (25–28). This technology provides tremendous detail for cellular analysis of multiple cell populations simultaneously. Further, we have recently shown sensitive and reproducible detection of immune cell subsets starting with as few as 10,000 cells demonstrating that CyTOF has excellent sensitivity for quantitative studies of limited sample size (29). We have undertaken the current study to demonstrate the feasibility of this powerful technique in translational investigations and the advantages of quantitative multiparameter phenotypic and functional profiles from airway samples of defined heterogeneous patient cohorts.

Materials and methods

Enrollment of human subjects and sputum collection

Healthy controls and asthmatic or CF subjects age > 18 yrs were enrolled with written informed consent through the Yale Center for Asthma and Airway Diseases (YCAAD) phenotyping protocol which collects clinical characteristics and induced sputum samples according to our long-standing protocols (30–33) (Table 1). Enrolled asthmatic subjects have a diagnosis of asthma based on National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) guidelines, historical evidence of variable airflow obstruction determined by an improvement in FEV1 > 12% and 200 ml compared to baseline after a short-acting bronchodilator, or treatment with corticosteroids, 20% diurnal variation of peak expiratory flow rates on 2 days over a 2–3 week period, or methacholine reactivity causing a 20% decrease in FEV1 (PC20) of <8 mg/ml. We excluded subjects who are smokers, or have other chronic lung disease (e.g. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis) or other severe chronic conditions (CHF, renal failure, liver disease, chronic viral infections). CF subjects had a confirmed diagnosis of CF according to Cystic Fibrosis Foundation guidelines based on clinical manifestations of CF, sweat chloride testing, and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene mutation analysis (34). Healthy controls were non-smokers without fever who took no antibiotics at the time of sputum induction. Airway cell samples are acquired by sputum induction with hypertonic saline as described previously (30–33).

Table 1.

Study Subject Demographics, Clinical Status, and Sputum Collection

| Study Group | Study ID | Age | Gender | Race | BMI | FEV1 (%) | Asthma Severity∞ | ICS Total/day (μg) | Gram neg | Cell # (x 106) | Viability (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | A1 | 60 | F | White | 36.99 | 0.89 (39%) | SEV | 0 | 8.0 | 88.0 | |

| N = 7 | A2 | 42 | F | African American | 56.94 | 1.91 (71%) | SEV | 640 | 5.0 | 85.0 | |

| A3 | 50 | M | African American | 27.39 | 2.03 (56%) | SEV∞ | 1000 * | 2.0 | 57.0 | ||

| A4 | 52 | F | African American | 23.63 | 1.98 (84%) | MOD∞ | 640 ** | 3.0 | 53.0 | ||

| A5 | 57 | F | African American | 46.86 | 1.04 (39%) | SEV | 0 | 2.5 | 67.0 | ||

| A6 | 59 | F | White | 62.28 | 1.21 (45%) | SEV | 1000 | 4.0 | 90.0 | ||

| A7 | 66 | M | White | 23.73 | 3.04 (83%) | MOD | 80 | 1.3 | 78.5 | ||

| CF | CF1 | 29 | M | White | 26.01 | 1.81 (51%) | + | 1.1 | 70.0 | ||

| N = 11 | CF2 | 30 | M | White | 24.01 | 2.69 (68%) | − | 2.2 | 91.0 | ||

| CF3 | 26 | M | White | 20.65 | 3.24 (76%) | − | 1.2 | 83.0 | |||

| CF4 | 41 | M | White | 21.84 | 1.29 (32%) | 500 | + | 1.1 | 67.0 | ||

| CF5 | 36 | M | White | 25.14 | 1.18 (28%) | + | 1.3 | 90.0 | |||

| CF6 | 32 | F | White | 21.08 | 1.98 (66%) | 1000 | + | 16.2 | 89.6 | ||

| CF7 | 25 | F | White | 21.21 | 1.53 (54%) | + | 3.6 | 80.0 | |||

| CF8 | 37 | M | White | 25.14 | 1.11 (26%) | + | 21.3 | 94.0 | |||

| CF9 | 35 | M | White | 21.93 | 1.80 (44%) | + | 27.4 | 91.2 | |||

| CF10 | 58 | F | White | 25.82 | 1.17 (50%) | 320 | + | 16.9 | 77.0 | ||

| CF11 | 41 | M | White | 24.48 | 1.10 (26%) | 1000 | + | 4.2 | NT | ||

| Healthy Control | HC1 | 64 | F | White | 25.00 | NT | 1.5 | 71.0 | |||

| N = 3 | HC2 | 35 | F | White | 32.80 | NT | 0 | 4.0 | 88.0 | ||

| HC3 | 49 | F | Asian | 33.00 | NT | 0.8 | 37.0 |

Enrolled study subjects were tested for Body-mass index (BMI) and % forced expired value (FEV1) as shown; NT not tested. Severity criteria for diagnosis of Severe (SEV) or Moderate (MOD) asthma based on clinical findings;

asthma flare;

OCS oral corticosteroids for * 8 days or ** 30 days. Sputum microbiology from CF patients was reported by the Yale-New Haven Clinical Microbiology Laboratory according to guidelines from the American Society for Microbiology and the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. + indicates growth of Gram-negative respiratory pathogens in sputum after 5 days of incubation. Cell number and viability were determined microscopically prior to CyTOF.

Sputum cell isolation and stimulation

On the day of collection, mucus plugs are dissected from saliva by dissecting microscope, washed, dissolved in DTT (Calbiochem/EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), treated with 150 U/ml Collagenase IV (Worthington Chemical, Lakewood, NJ) and 25 U/ml DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 15 min at 37 °C, and centrifuged to generate cell and supernatant as described (7,30–32). Sputum was processed on the day of isolation using sputolysin (Calbiochem) to generate cell suspension. Sputum from CF subjects was processed using a similar protocol but without DTT and using mechanical disruption of sputum according to standardized protocols (35). Cell yield was counted and samples with >20% squamous cells were considered contaminated and were not analyzed. Cell viability was assessed microscopically after purification and similar values were obtained in CyTOF by exclusion of cisplatin. Cells were incubated in medium alone or with stimulated with 0.5 μg/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h followed by incubation with 3.0 μg/ml Brefeldin A (eBioscience, San Jose, CA) and 2 μM Monensin (eBioscience) for an additional 4 h.

CyTOF marker labeling and detection

Live cell suspensions were labeled on the day of isolation in 400 μl RPMI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in wells of a 96-deepwell plate according to established conditions for CyTOF (29). Viability of cells was identified by incubation with 5 μM cisplatin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 5 min at RT and quenched with 500 μl fetal bovine serum. Cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C with a 50 μl cocktail of metal conjugated antibodies including Qdot-HLA-DR, 142Nd-CD11b, 146Nd-CD8α, 147Sm-CD20, 148Nd-CD16, 154Sm-CD45, 155Gd-CD4, 159Tb-CD11c, 160Gd-CD14, 161Dy-pan-Cytokeratin, 162Dy-CD80, 164Dy-CD15, 165Ho-CD163, 170Er-CD3, 171Yb-CD66b, 174Yb-CD62L and 176Yb-CD56 (Table 2). Metal-conjugated antibodies were purchased from either Fluidigm/DVS Science (Sunnyvale, CA), Longwood Medical Area CyTOF Antibody Resource and Core (Boston, MA), or conjugated in house using Max-PAR kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Fluidigm). Cells were washed, fixed and permeabilized (BD Pharm LyseTM lysing solution, BD FACS Permeabilizing Solution 2, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for 10 min each at RT. For intracellular labeling, cells were incubated for 45 min at 4°C with a 50 μl antibody cocktail for labeling of cytokines 150Nd-MIP-1β, 152Sm-TNFα, 156Gd-IL-6, 168Er-IFN-γ, and 173Yb-IL-8. Total cells were identified by DNA intercalation (0.125 μM Iridium-191/193 or MaxPar® Intercalator-Ir, Fluidigm/DVS Science) in 2% PFA at 4°C overnight. A set of 4 metal-labeled calibration beads (Q™ Four Element Calibration Beads) was included with each sample for instrument normalization (36). Labeled samples were assessed by the CyTOF2 instrument (Fluidigm) using a flow rate of 0.045 ml/min (29).

Table 2.

Antibodies used for mass cytometry.

| Isotope | Ab | Vendor | Catalog # | Clone |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q-dot | HLA-DR | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Q22158 | Tü36 |

| 142Nd | CD11b | BWH* | V03005 | M1/70 |

| 146Nd | CD8a | DVS | 3146001B | RPA-T8 |

| 147Sm | CD20 | DVS | 3147001B | 2H7 |

| 148Nd | CD16 | DVS | 3148004B | 3G8 |

| 150Nd | MIP-1β | DVS | 3150004B | D21-135 |

| 152Sm | TNF-α | DVS | 3152001B | Mab11 |

| 154Sm | CD45 | DVS | 3154001B | HI30 |

| 155Gd | CD4 | BWH* | V04286 | RPA T4 |

| 156Gd | IL-6 | DVS | 3156011B | MQ2-13AS |

| 159Tb | CD11c | DVS | 3159001B | Bu15 |

| 160Gd | CD14 | DVS | 3160001B | M5E2 |

| 161Dy | Cytokeratin | BioLegend | 628601 | C-11 |

| 162Dy | CD80 | DVS | 3162010B | 2D10.4 |

| 164Dy | CD15 | DVS | 3164001B | W6D3 |

| 165Ho | CD163 | DVS | 3165017B | GHI/61 |

| 168Er | IFN-γ | DVS | 3168005B | B27 |

| 170Er | CD3 | DVS | 3170001B | UCHT1 |

| 171Yb | CD66b | BWH* | V10178 | G10F5 |

| 173Yb | IL-8 | BioLegend** | 511402 | E8N1 |

| 174Yb | CD62L | BWH* | V00751 | DREG-56 |

| 176Yb | CD56 | DVS | 3176009B | N901 |

Brigham and Women’s CyTOF Antibody Resource;

in house conjugation using Max-Par kit

Cell subset identification and statistical analysis

To identify cell subsets present in sputum samples, .fcs-files generated by CyTOF were analyzed after exclusion of debris (Iridiumlow, DNAlow), multi-cell events (Iridiumhi, DNAhi), and dead cells (cisplatinlow) as described previously (29). High dimensional data measured by CyTOF was visualized using tSNE into a two-dimensional map showing neighborhoods of similar cells from the original representation (37,38). Parameters included were CD3, CD4, CD8, CD11c, CD15, CD16, CD20, CD45, CD56, CD66b, CD163, and cytokeratin (CK). To compare responses to stimulation, the pre-gated viable single cells were clustered using Citrus version 0.08 (https://github.com/nolanlab/citrus) (39) using 5000 events from each sample for clustering with 1% of the minimum cluster size. SAM and pamr were used as model types for analyzing abundance and median value, respectively. Significance was inferred for false discovery rate (FDR) < 1% (q < 0.01) for SAM model and cross validation error rate < 20% for pamr model. Each comparison was run at least 3 times to ensure reproducibility (39). Manual gating for validation was performed using Flowjo software (Tree Star, OR). Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 6 software (Graphpad, La Jolla, CA). Mann-Whitney test was used for comparisons between asthmatic, CF, and healthy control groups. For each group, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test was used for paired data between mock and LPS treatment.

Results

Detection of multiple cell lineages in sputum

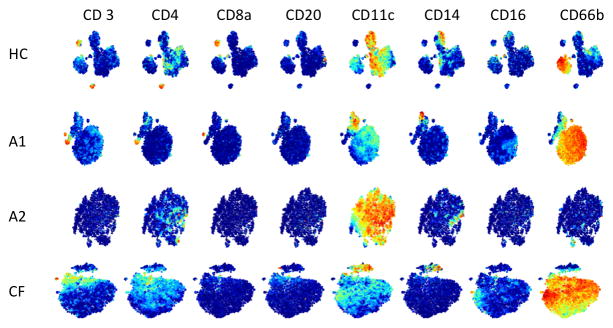

In depth investigation of airway immune pathogenesis requires reproducible assessment of cell subsets and functional status of the relevant airway cells. We characterized cell phenotypes from induced sputum on the day of isolation from healthy controls (n=3) and patients diagnosed with asthma (n=7) or CF (n=11). All sputum samples used in this study had high viability (Table 1; average 77.4 ± 15.2%). The cell yield from induced sputum averaged 6.1 x 106 ± x (range 0.8—27.4) with the lowest recovery from healthy controls and higher cell numbers, as expected, from asthmatic and CF subjects (Table 1). To distinguish cell phenotypes and capture the heterogeneity of the cells in sputum, we designed an antibody panel to simultaneously identify multiple cell lineages that accumulate in asthma or CF (15–19) (Table 2, n= 22 antibodies). Gating of live single cells (Figure S1) in CyTOF distinguished lineage specific staining of cytokeratin+ non-immune cells which averaged 15.4–18.1% (range 1.7%–48.2%) of cells in asthmatics and healthy controls but were considerably lower in CF subjects (5.6 ± 1.9%; range 0.5%–17.8%). The majority of cells (59.0–71.7%) from all three groups were CD45+ immune cells that labeled predominantly with neutrophil and monocyte/macrophage markers, as was expected from previous studies using flow cytometry (15–19). Given the small sample size and the well-recognized heterogeneity of asthmatic patients, we assessed frequency of immune cell subsets from patients individually (Figure 1). Sputum datasets were analyzed using tSNE, a dimensionality reduction method that emphasizes neighborhood or cluster-structure when visualized (37,38). Analysis of CD45+ cytokeratin- immune cells by tSNE highlights distinct clusters of cells in sputum and detected multiple cell lineages in sputum including T (CD3+) and B (CD3−CD20+) lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages (HLA-DR+CD14+CD11C+), and granulocytes (CD66b+) (Figure 1 and Figure S2). Total lymphocyte presence in sputum is quite low and consists of relatively more T cells than B cells. Similarly, NK cells were infrequent in sputum (Figure S2).

Figure 1. Visualization of sputum immune cell populations.

Cells from sputum were labeled with metal-conjugated antibodies for immunophenotyping and analyzed by CyTOF. Live cells from representative healthy control (HC) and individual patients with asthma (A1, A2) or cystic fibrosis (CF) were analyzed using tSNE plots. Each dot represents a single-nucleated live immune cell (CD45+, cytokeratin−) including T cells (CD3+, CD4+, CD8+), B cells (CD20+), monocyte/macrophage subsets (CD11c+, CD14+, CD16+), and PMN (CD66b+). Rows correspond to healthy control (HC) or asthmatic (A1 and A2) or CF subjects (CF) with each plot colorized to red for high expression of the respective marker.

Distinct populations of cells distinguish disease cohorts

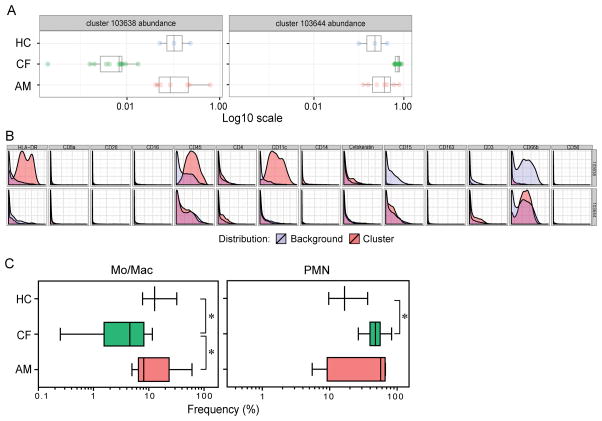

To distinguish key features of airway immune cells, we compared healthy controls with patients. Both asthmatic and CF patients had elevated levels of infiltrating cells and, notably, different asthmatic patients showed distinct profiles of cells reflecting the heterogeneity of their clinical condition (Figure 1), e.g., predominantly monocytic or more neutrophilic, which is typical of only some asthma clinical clusters (7). As expected, sputum from CF patient was predominantly labeled for neutrophil (PMN), consistent with previous studies (40), and correlating with an average of 85% PMN detected morphologically from cytospin counts (data not shown). To identify different phenotypic clusters of cells between the groups and quantify differences in cell populations, we examined CyTOF datasets from each subject group for analysis using the unsupervised clustering algorithm Citrus (39). When we quantified airway cells between the three cohorts using this unbiased approach, we noted significant differences in the proportion of macrophages with asthmatic and healthy subjects having a higher frequency of macrophages than CF patients, while CF subjects had a higher frequency of PMN than healthy subjects (Figure 2A, B). These clusters were confirmed by manual gating (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Automated clustering analysis of cell subsets in human sputum.

The viable single cells from sputum of asthmatic (AM, n = 7), CF (n = 11), and healthy (HC, n = 3) subjects were analyzed by the unsupervised hierarchical clustering algorithm Citrus on the basis of the expression of markers in each sample. Abundance of subsets was compared using SAM (FDR < 1%) between all three groups. (A) Abundance of cells within the identified distinguishing clusters. (B) Phenotypic plots of the clusters of sputum cells with distinct abundance between subjects. The phenotypic plots represent the clusters with different abundance between the groups. All the phenotypic plots are representative of at least three independent runs. (C) Hierarchical clusters confirmed by manual gating. Mo/Mac, monocytes/macrophages, CD45+HLA-DR+CD14+CD11c+; PMN, CD45+CD66b+. * indicates p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test was used for comparisons between cohorts.

Notably, there was a significantly higher frequency of CD80+ PMN from CF compared to asthma (32.7 ± 4.5 vs 13.6 ± 3.3, p =0.018; Figure S3) as well as a trend of increase compared to healthy controls (16.5 ± 4.3, p = 0.087, Figure S3), consistent with previous reports of functional reprogramming of PMN in CF (41). Further, a trend towards elevated levels of CD11b was noted in PMN of asthmatic patients taking oral corticosteroids compared to those without (mean ± s.e.m.: 81.4 ± 5.2 vs 53.7 ± 9.3, p = 0.0571; Figure S4), suggesting lower levels of activation, but did not quite reach significance likely due to the small number of subjects per subgroup.

Functional Responses of airway cells

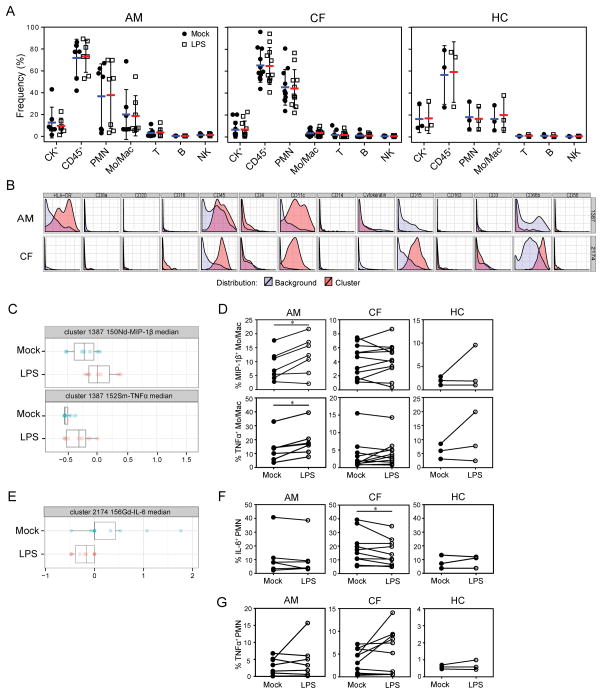

The in depth analysis possible with CyTOF supports investigation of functional status that may be relevant to the pathogenesis of airway inflammation and clinical condition. Thus we investigated whether cells from induced sputum would retain functional responses that could be detected by a CyTOF antibody panel. Sputum samples from asthmatic, CF, and healthy controls were stimulated with LPS (0.5 μg/ml) for 6 hr and labeled for lineage-specific production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Figure S5). The number of cells recovered following treatment with LPS was not significantly different for any group (Figure 3A), indicating that the cells were viable and tolerated this relatively potent treatment. Through hierarchical clustering Citrus analysis (Figure 3B, 3C, 3E) and manual gating (Figure 3D, 3F) of live cells from samples of three cohorts, we noted induction of cytokines MIP-1β and TNFα by monocyte/macrophages in asthmatic samples and a decrease of IL-6 by PMN in CF samples following LPS treatment. These results indicate that this method can not only detect production of cytokines relevant to increased inflammation in the airway, but also highlight the distinctions between inflammatory processes in these airway diseases. The cytokine production showed substantial variability among subjects, which likely reflects the diverse characteristic of asthmatics and CF. In addition, we noted dramatic variation in responsiveness of PMN in asthmatic and CF sputum, with a portion of the subjects showing strong induction of TNF following stimulation with LPS, some showing a reduction, and some with no response at all (Figure 3G). In our pilot study no significant differences were detected between the asthmatic subjects taking > 600 μg oral steroids (n=4) in comparison to those taking lower doses or without steroids (n=3), or for the CF subjects with gram negative colonization (n=9)--who would thus be exposed to LPS in vivo--to those without (n=2). Future studies of larger defined patient cohorts may employ these methods to distinguish airway cell function.

Figure 3. Functional analysis of sputum cell subsets.

Sputum single cell suspensions were incubated with 0.5 μg/ml LPS or medium alone (mock) for 6 h. Cells were labeled with metal-conjugated antibodies against cell lineage markers as well as functional markers CD80, IL-6, IL-8, IFNγ, MIP-1β, TNFα, CD11b and CD62L and analyzed by CyTOF. (A) Frequency of each cell subset in sputum from asthma (AM), CF, and healthy control (HC) subjects obtained by manual gating was not altered by treatment with LPS. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test was used for paired data between mock and LPS treatment, all groups NS. CK, cytokeratin; Mo/Mac, monocytes/macrophages; T, T cells; B, B cells; NK, Natural Killer cells. (B) The live single cells from asthmatic, CF and healthy sputum were analyzed by Citrus. The phenotypic plots represent the clusters with different median intensity of indicated markers (C and E) between the two treatments. Results obtained by manual gating show (D) Frequency of MIP-1β-or TNFα-expressing monocytes/macrophages in sputum from three cohorts; (F, G) Frequency of IL-6- or TNFα-expressing PMN in sputum from three groups. * indicates p < 0.05, Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Discussion

Here we have demonstrated the utility of mass cytometry to define functional cell subsets in primary airway cells from asthmatic and CF patients and healthy controls using a panel of 22 phenotypic and functional antibodies. Our initial CyTOF airway panel, while relatively modest by CyTOF standards, validates detection of major sputum cell populations and functional responses and can serve as a backbone for future studies with an additional ~15–20 open channels to provide substantial flexibility. Given the high sensitivity and dimensionality of this method, a full panel of 42 markers will allow more definitive characterization of immune subsets as well as populations of non-immune cytokeratin cells from sputum that cannot be identified or fully characterized by traditional methods of flow cytometry or light microscopy (cytospin) determination.

Our current study is limited in sample size and with a larger cohort we might have detected additional differences. Valuable markers to include in future studies will be BDCA-1, BDCA-3, CD123 and BDCA-2 for dendritic cells (19,42), IgE and CCR3 for basophils (43,44), and c-Kit for mast cells (45). Specialized panels can be developed for CF as the CD16 marker to distinguish PMN and eosinophils is often absent in CF (41). Moreover, guides to distinguish monocytes and macrophages--which rely on SSC parameters (17,18) or auto-fluorescence (19) in flow cytometry--can be resolved in future studies by expanding the panel beyond the many shared markers (e.g., CD11c, HLA-DR, CD14).

An in depth analysis of cell phenotype and functional status provides an opportunity to quantitatively immunophenotype subpopulations of airway cells in heterogeneous patient groups. These quantitative measurements will allow detailed investigation of cellular phenotypes in disease severity groups, as well as kinetics of responses in these cell types and activation of signal transduction pathways relevant to clinical status or therapeutic interventions. Single cell profiles can be correlated with levels of biomarkers of disease severity or status refractory to treatment modalities such as transcriptomic endotypes of asthma (TEA) (7), or the asthma biomarker chitinase-like protein, YKL-40, which is increased in the circulation and airways with disease severity, and for which a gene polymorphism is associated with asthma, lung function and bronchial hyper-responsiveness (30,31,46). Validation of our multiparameter antibody panels for airway immune cells will enable the most rapid adoption of this technology for investigation of asthma and other airway diseases. Through collection of high-quality data employing validated reference standards (47,48), future studies approaching a single cell resolution will undoubtedly improve our understanding of immune responses in the airway.

In addition, CyTOF analysis can be combined with other recent advances in technology, such as intracellular signaling pathways with high-resolution digital imaging (49) and transcriptional profiling (7). These quantitative assays are feasible to perform in sputum samples and open a new avenue for multidimensional profiling of functional cells in relevant patient cohorts to investigate cellular mechanisms and allow more individualized diagnosis and targeted therapeutic options for refractory patients.

Supplementary Material

Viable single cells from sputum were labeled for CyTOF and were gated following exclusion of debris (DNA−), doublets (DNAhi), and dead cells (Cisplatin+). Cell subsets were defined by cell lineage markers: cytokeratin+ non-immune cells (CD45–CK+), T cells (CD45+CD3+), B cells (CD45+CD20+), PMN (CD45+CD66b+), NK cells (CD45+CD56+), and monocyte/macrophages (CD45+HLA-DR+CD14+/CD11c+/CD163+).

Cells from sputum were labeled with metal-conjugated antibodies for immunophenotyping and analyzed by CyTOF as in Figure 1. Live cells from healthy control (HC) and individual patients with asthma (A1, A2) or cystic fibrosis (CF) were analyzed using tSNE plots. Each dot represents a single-nucleated live immune cell (CD45+, cytokeratin−) including T cells (CD3+, CD4+, CD8+), B cells (CD20+), monocyte/macrophage subsets (CD11c+, CD14+, CD16+), and PMN (CD66b+). Rows correspond to healthy control (HC) or asthmatic (A1 and A2) or CF subjects (CF) with each plot colorized to red for high expression of the respective marker.

PMN from sputum of asthmatic (AM, n = 7), CF (n = 11) and healthy (HC, n = 3) subjects were compared for expression of CD80. Data shown are frequency of CD80-expressing PMN in sputum from three cohorts.

Expression of CD11b expression on PMN from sputum of asthmatic subjects divided according to level of oral corticosteroids (≥600 μg dose (+) steroid group, <600 μg dose (−) steroid group). Expression of CD11b was compared in the presence or absence of LPS treatment. Data shown are frequency of CD11b-expressing PMN in sputum samples.

(A) Monocytes/macrophages from sputum of asthmatic (AM, n = 7), CF (n = 11) and healthy (HC, n = 3) subjects were compared for production of MIP-1β and TNFα between mock and LPS-treated groups. Plots represent the frequency of MIP-1β- or TNFα-expressing monocytes/macrophages in representative sputum samples. (B) PMN from all three groups of sputum were compared for production of IL-6 and TNFα between mock and LPS-treated groups. Plots show the frequency of IL-6- or TNFα-expressing PMN in the representative sputum samples.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (HHS N272201100019C, R01 HL118346, R01 HL-095390, 1K01HL125514-01). None of the authors have any commercial or other association that may pose a conflict of interest for this work. The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable assistance of Ms. Carole Holm.

Abbreviations

- CF

Cystic Fibrosis

- Eos

Eosinophils

- CyTOF

Mass cytometry by time of flight

- PMN

polymorphonuclear leukocyte

- TEA

transcriptomic endotypes of asthma

References

- 1.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Liu X. Asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality: United States, 2005–2009. Natl Health Stat Report. 2011:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohn L, Elias JA, Chupp GL. Asthma: mechanisms of disease persistence and progression. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:789–815. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, Teague WG, Li H, Li X, D’Agostino R, Jr, Castro M, Curran-Everett D, Fitzpatrick AM, et al. Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:315–23. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0896OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, Jia G, Abbas AR, Ellwanger A, Koth LL, Arron JR, Fahy JV. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:388–95. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0392OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng D, Xue Z, Yi L, Shi H, Zhang K, Huo X, Bonser LR, Zhao J, Xu Y, Erle DJ, et al. Epithelial interleukin-25 is a key mediator in Th2-high, corticosteroid-responsive asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:639–48. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0505OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baines KJ, Simpson JL, Wood LG, Scott RJ, Fibbens NL, Powell H, Cowan DC, Taylor DR, Cowan JO, Gibson PG. Sputum gene expression signature of 6 biomarkers discriminates asthma inflammatory phenotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:997–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan X, Chu J, Gomez J, Koenigs M, Holm C, He X, Perez MF, Zhao H, Mane S, Martinez FD, et al. Non-invasive analysis of the sputum transcriptome discriminates clinical phenotypes of asthma. Amer J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:1116–1125. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201408-1440OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowe SM, Miller S, Sorscher EJ. Cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1992–2001. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dwyer M, Shan Q, D’Ortona S, Maurer R, Mitchell R, Olesen H, Thiel S, Huebner J, Gadjeva M. Cystic fibrosis sputum DNA has NETosis characteristics and neutrophil extracellular trap release is regulated by macrophage migration-inhibitory factor. J Innate Immun. 2014;6:765–79. doi: 10.1159/000363242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stoltz DA, Meyerholz DK, Welsh MJ. Origins of cystic fibrosis lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1574–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1300109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartl D, Gaggar A, Bruscia E, Hector A, Marcos V, Jung A, Greene C, McElvaney G, Mall M, Doring G. Innate immunity in cystic fibrosis lung disease. J Cyst Fibros. 2012;11:363–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foundation CF. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation; Bethesda, Maryland: 2015. 2014 Annual Data Report. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schleich FN, Manise M, Sele J, Henket M, Seidel L, Louis R. Distribution of sputum cellular phenotype in a large asthma cohort: predicting factors for eosinophilic vs neutrophilic inflammation. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-13-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore WC, Hastie AT, Li X, Li H, Busse WW, Jarjour NN, Wenzel SE, Peters SP, Meyers DA, Bleecker ER, et al. Sputum neutrophil counts are associated with more severe asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1557–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sedgwick JB, Calhoun WJ, Vrtis RF, Bates ME, McAllister PK, Busse WW. Comparison of airway and blood eosinophil function after in vivo antigen challenge. J Immunol. 1992;149:3710–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dominguez Ortega J, Leon F, Martinez Alonso JC, Alonso Llamazares A, Roldan E, Robledo T, Mesa M, Bootello A, Martinez-Cocera C. Fluorocytometric analysis of induced sputum cells in an asthmatic population. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2004;14:108–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lay JC, Peden DB, Alexis NE. Flow cytometry of sputum: assessing inflammation and immune response elements in the bronchial airways. Inhal Toxicol. 2011;23:392–406. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2011.575568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vidal S, Bellido-Casado J, Granel C, Crespo A, Plaza V, Juarez C. Flow cytometry analysis of leukocytes in induced sputum from asthmatic patients. Immunobiology. 2012;217:692–7. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freeman CM, Crudgington S, Stolberg VR, Brown JP, Sonstein J, Alexis NE, Doerschuk CM, Basta PV, Carretta EE, Couper DJ, et al. Design of a multi-center immunophenotyping analysis of peripheral blood, sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in the Subpopulations and Intermediate Outcome Measures in COPD Study (SPIROMICS) J Transl Med. 2015;13:19. doi: 10.1186/s12967-014-0374-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lloyd CM, Hessel EM. Functions of T cells in asthma: more than just T(H)2 cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:838–48. doi: 10.1038/nri2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreira AP, Hogaboam CM. Macrophages in allergic asthma: fine-tuning their pro- and anti-inflammatory actions for disease resolution. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011;31:485–91. doi: 10.1089/jir.2011.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell C, Provost K, Niu N, Homer R, Cohn L. IFN-gamma acts on the airway epithelium to inhibit local and systemic pathology in allergic airway disease. J Immunol. 2011;187:3815–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ungurs MJ, Sinden NJ, Stockley RA. Progranulin is a substrate for neutrophil-elastase and proteinase-3 in the airway and its concentration correlates with mediators of airway inflammation in COPD. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;306:L80–7. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00221.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spitzer MH, Nolan GP. Mass Cytometry: Single Cells, Many Features. Cell. 2016;165:780–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bandura DR, Baranov VI, Ornatsky OI, Antonov A, Kinach R, Lou X, Pavlov S, Vorobiev S, Dick JE, Tanner SD. Mass cytometry: technique for real time single cell multitarget immunoassay based on inductively coupled plasma time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2009;81:6813–22. doi: 10.1021/ac901049w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bendall SC, Simonds EF, Qiu P, Amir el AD, Krutzik PO, Finck R, Bruggner RV, Melamed R, Trejo A, Ornatsky OI, et al. Single-cell mass cytometry of differential immune and drug responses across a human hematopoietic continuum. Science. 2011;332:687–96. doi: 10.1126/science.1198704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaudilliere B, Fragiadakis GK, Bruggner RV, Nicolau M, Finck R, Tingle M, Silva J, Ganio EA, Yeh CG, Maloney WJ, et al. Clinical recovery from surgery correlates with single-cell immune signatures. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:255ra131. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strauss-Albee DM, Fukuyama J, Liang EC, Yao Y, Jarrell JA, Drake AL, Kinuthia J, Montgomery RR, John-Stewart G, Holmes S, et al. NK cell repertoire diversity reflects immune experience and predicts viral susceptibility. Sci Trans Med. 2015;7:297ra115. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac5722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao Y, Liu R, Shin MS, Trentalange M, Allore H, Nassar A, Kang I, Pober J, Montgomery RR. CyTOF supports efficient detection of immune cell subsets from small samples. J Immunol Methods. 2014;415:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chupp GL, Lee CG, Jarjour N, Shim YM, Holm CT, He S, Dziura JD, Reed J, Coyle AJ, Kiener P, et al. A chitinase-like protein in the lung and circulation of patients with severe asthma. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2016–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ober C, Tan Z, Sun Y, Possick JD, Pan L, Nicolae R, Radford S, Parry RR, Heinzmann A, Deichmann KA, et al. Effect of variation in CHI3L1 on serum YKL-40 level, risk of asthma, and lung function. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1682–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin JC, Gagnon L, He X, Baum ED, Karas DE, Chupp GL. Improvement in asthma control and inflammation in children undergoing adenotonsillectomy. Pediatr Res. 2014;75:403–408. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coon TA, McKelvey AC, Lear T, Rajbhandari S, Dunn SR, Connelly W, Zhao JY, Han S, Liu Y, Weathington NM, et al. The proinflammatory role of HECTD2 in innate immunity and experimental lung injury. Sci Trans Med. 2015;7:295ra109. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab3881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farrell PM, Rosenstein BJ, White TB, Accurso FJ, Castellani C, Cutting GR, Durie PR, Legrys VA, Massie J, Parad RB, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in newborns through older adults: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation consensus report. J Pediatr. 2008;153:S4–S14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sagel SD, Kapsner R, Osberg I, Sontag MK, Accurso FJ. Airway inflammation in children with cystic fibrosis and healthy children assessed by sputum induction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1425–31. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.8.2104075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finck R, Simonds EF, Jager A, Krishnaswamy S, Sachs K, Fantl W, Pe’er D, Nolan GP, Bendall SC. Normalization of mass cytometry data with bead standards. Cytometry A. 2013;83:483–94. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Maaten L, Hinton G. Visualizing Data using t-SNE. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2008;9:2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amir el AD, Davis KL, Tadmor MD, Simonds EF, Levine JH, Bendall SC, Shenfeld DK, Krishnaswamy S, Nolan GP, Pe’er D. viSNE enables visualization of high dimensional single-cell data and reveals phenotypic heterogeneity of leukemia. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:545–52. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruggner RV, Bodenmiller B, Dill DL, Tibshirani RJ, Nolan GP. Automated identification of stratifying signatures in cellular subpopulations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E2770–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408792111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hector A, Jonas F, Kappler M, Feilcke M, Hartl D, Griese M. Novel method to process cystic fibrosis sputum for determination of oxidative state. Respiration. 2010;80:393–400. doi: 10.1159/000271607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tirouvanziam R, Gernez Y, Conrad CK, Moss RB, Schrijver I, Dunn CE, Davies ZA, Herzenberg LA, Herzenberg LA. Profound functional and signaling changes in viable inflammatory neutrophils homing to cystic fibrosis airways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4335–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712386105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mukai K, Gaudenzio N, Gupta S, Vivanco N, Bendall SC, Maecker HT, Chinthrajah RS, Tsai M, Nadeau KC, Galli SJ. Assessing basophil activation by using flow cytometry and mass cytometry in blood stored 24 hours before analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.04.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hausmann OV, Gentinetta T, Fux M, Ducrest S, Pichler WJ, Dahinden CA. Robust expression of CCR3 as a single basophil selection marker in flow cytometry. Allergy. 2011;66:85–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Voehringer D, Rosen DB, Lanier LL, Locksley RM. CD200 receptor family members represent novel DAP12-associated activating receptors on basophils and mast cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54117–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Metcalfe DD, Pawankar R, Ackerman SJ, Akin C, Clayton F, Falcone FH, Gleich GJ, Irani AM, Johansson MW, Klion AD, et al. Biomarkers of the involvement of mast cells, basophils and eosinophils in asthma and allergic diseases. World Allergy Organ J. 2016;9:7. doi: 10.1186/s40413-016-0094-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ober C, Chupp GL. The chitinase and chitinase-like proteins: a review of genetic and functional studies in asthma and immune-mediated diseases. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;9:401–8. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283306533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kleinsteuber K, Corleis B, Rashidi N, Nchinda N, Lisanti A, Cho JL, Medoff BD, Kwon D, Walker BD. Standardization and quality control for high-dimensional mass cytometry studies of human samples. Cytometry A. 2016 doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22935. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montgomery RR. High Standards for High Dimensional Investigations. Cytometry A. 2016 doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22992. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qian F, Montgomery RR. Quantitative imaging of lineage specific Toll-like receptor mediated signaling in monocytes and dendritic cells from small samples of human blood. JoVE. 2012;62:e3741. doi: 10.3791/3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Viable single cells from sputum were labeled for CyTOF and were gated following exclusion of debris (DNA−), doublets (DNAhi), and dead cells (Cisplatin+). Cell subsets were defined by cell lineage markers: cytokeratin+ non-immune cells (CD45–CK+), T cells (CD45+CD3+), B cells (CD45+CD20+), PMN (CD45+CD66b+), NK cells (CD45+CD56+), and monocyte/macrophages (CD45+HLA-DR+CD14+/CD11c+/CD163+).

Cells from sputum were labeled with metal-conjugated antibodies for immunophenotyping and analyzed by CyTOF as in Figure 1. Live cells from healthy control (HC) and individual patients with asthma (A1, A2) or cystic fibrosis (CF) were analyzed using tSNE plots. Each dot represents a single-nucleated live immune cell (CD45+, cytokeratin−) including T cells (CD3+, CD4+, CD8+), B cells (CD20+), monocyte/macrophage subsets (CD11c+, CD14+, CD16+), and PMN (CD66b+). Rows correspond to healthy control (HC) or asthmatic (A1 and A2) or CF subjects (CF) with each plot colorized to red for high expression of the respective marker.

PMN from sputum of asthmatic (AM, n = 7), CF (n = 11) and healthy (HC, n = 3) subjects were compared for expression of CD80. Data shown are frequency of CD80-expressing PMN in sputum from three cohorts.

Expression of CD11b expression on PMN from sputum of asthmatic subjects divided according to level of oral corticosteroids (≥600 μg dose (+) steroid group, <600 μg dose (−) steroid group). Expression of CD11b was compared in the presence or absence of LPS treatment. Data shown are frequency of CD11b-expressing PMN in sputum samples.

(A) Monocytes/macrophages from sputum of asthmatic (AM, n = 7), CF (n = 11) and healthy (HC, n = 3) subjects were compared for production of MIP-1β and TNFα between mock and LPS-treated groups. Plots represent the frequency of MIP-1β- or TNFα-expressing monocytes/macrophages in representative sputum samples. (B) PMN from all three groups of sputum were compared for production of IL-6 and TNFα between mock and LPS-treated groups. Plots show the frequency of IL-6- or TNFα-expressing PMN in the representative sputum samples.