Abstract

The trend towards decriminalization of cannabis (marijuana) continues sweeping across the United States. Colorado has been a leader of legalization of medical and recreational cannabis use. The growing public interest in the medicinal properties of cannabis and its use by patients with a variety of illnesses including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) makes it important for pediatric gastroenterologists to understand this movement and its potential impact on patients. This article describes the path to legalization and “medicalization” of cannabis in Colorado as well as the public perception of safety despite the known adverse health effects of use. We delineate the mammalian endocannabinoid system and our experience of caring for children and adolescents with IBD in an environment of increasing awareness and acceptance of its use. We then summarize the rationale for considering that cannabis may have beneficial as well as harmful effects for IBD patients. Finally, we highlight the challenges federal laws impose on conducting research on cannabis in IBD. The intent of this article is to inform health care providers about the issues around cannabis use and research in adolescents and young adults with IBD.

Keywords: cannabis, marijuana, inflammatory bowel disease, cannabidiol (CBD), tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), research, pediatric

Cannabis legalization in Colorado

As of fall 2015, Colorado was one of 24 states that legalized cannabis use for medical purposes and one of 4 states that allowed adult use for recreational purposes 1. The passage of Amendment 20 in 2000 allowed adult Colorado residents with valid social security numbers and diagnosed with certain debilitating conditions or undergoing treatment for specific conditions to have possession of up to 2 ounces, and to grow up to 6 cannabis plants, for medicinal purposes . An identification card was required, as well as a doctor recommendation to use cannabis as treatment for these conditions (Table 1). A minor could receive a cannabis recommendation with consent of both parents and documentation from two physicians 2. Parents could then apply for a medical marijuana card on behalf of their child, be listed as the child’s caregiver on the card, and have permission to transport medical marijuana from a medical marijuana dispensary to their child. In this way, Colorado voters defined cannabis as an acceptable treatment for a number of chronic conditions that produce subjective symptoms such as severe pain or nausea, and for cachexia 3.

Table 1.

Approved conditions for medical cannabis (marijuana) use per Colorado Constitution as of February 2016 46

| Cancer, Glaucoma, HIV or AIDS positive |

|---|

| Or a chronic or debilitating disease or medical condition that produces one or more of the following and which, in the physician’s professional opinion, may be alleviated by the medical use of cannabis: Cachexia Severe Nausea Severe pain Persistent muscle spasms Seizures |

With abolishment of the limitation of 5 “patients” to 1 “caregiver” and the U.S. Department of Justice indicating they would not likely prosecute individuals in compliance with state laws, applications for medical marijuana increased from 6000 in 2008 to 100,000 in 2012 and there were about 500 licensed dispensaries providing legal medical marijuana 4. In the vast majority (> 90%) the medical indication was severe pain. In 2012, Colorado voters enacted state constitutional Amendment 64 which legalized recreational cannabis use for those over 21 years old and provided for a system for regulation, taxation, and distribution, similar to alcohol. The expansion of the cannabis industry began in earnest in 2013. The first retail stores opened on January 1, 2014. In 2015, Colorado had $1 billion in sales, generating an expected $100 million in tax revenue, double that of 2014 5. For 2015, about 40% of revenue came from medical, and 60% from recreational use. Recreational cannabis, because of additional excise taxes designated to provide funds for schools and other projects, is more expensive than medical cannabis. Many habitual users still purchase the cheaper medical marijuana.

There is a process by which cannabis may be given to children under 18 years of age in Colorado. Two physicians must diagnose the patient with a qualifying debilitating condition, one of which must explain the possible risks and benefits in writing (there are no state guidelines on what this should include), and a parent must be a primary care giver. The state then provides the parent with a medical marijuana minor patient card. The amount that may be possessed is much higher for medical than for recreational purposes. A number of families have moved to Colorado, specifically to obtain cannabidiol (CBD) oil to treat severe seizures and neurologic conditions in their children 6.

Colorado has embarked on a social experiment “medicalizing” cannabis use and ending prohibition on recreational use. In its current state, the industry may be viewed as much like a pharmaceutical company that is in both production and retail. The product, however, is not one well-tested drug, but may contain over 100 chemicals in varying amounts, provided in different types of delivery systems (smoking, vaping, edibles, patches, oils, etc.), and with mainly anecdotal data on efficacy for treating human disease and an absence of information on safety and drug interactions. Health care providers will be asked by patients to discuss the medical marijuana issues 7.

Public Perception of Risk and Adverse Effects

The public perception of risk is quite low. In the “Monitoring the Future” report, the proportion of high school seniors who view regular use of cannabis as not having great risk was 60% in 2014, a figure that has been increasing steadily since 2004 8. However, substantial literature supports the view of significant adverse health effects with both short-term and long-term use, mainly on neurologic, cognitive, and mental health (Table 2)9. There may be acute psychotic symptoms during intoxication and several cases of apparent acute intoxication have been widely reported in the local media, including one 19 year old who jumped off a hotel balcony to his death, and a husband who shot his wife 10. Impaired adolescent driving while intoxicated with cannabis, especially in combination with alcohol, is another important issue. There has been an increase in the potency of THC content in marijuana from about 3% in the 1980s to 12% in 201211, raising concerns about the impact of this increased potency on the potential adverse effects of marijuana use. Another major concern is that cannabis ingested in an edible form is more difficult to titrate, unlike vaping or inhaling, as the effect may be delayed, and therefore higher doses may be consumed leading to intoxication. Heavy users have impaired memory for at least 1 week after abstinence; hyperemesis syndrome has been well described as have withdrawal symptoms. Addiction risk may be higher for those beginning heavy use in adolescence, and this behavior may predict progression to harder drugs 9, 12. These negative effects have both immediate and long term implications, leading the American Academy of Pediatrics 13 and the Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 14 to officially oppose the legalization of marijuana. These issues have not been widely reported in the public media. There are however particular challenges in interpreting the literature on cannabis use, as the data are often derived from studies of heavy and/or long term users where there are other potential confounding factors, such as use of other drugs, psychosocial and economic adversity 9. Further, the retrospective and correlational methodologies used do not allow for inferences of causality for any adverse outcomes associated with cannabis use.

Table 2.

| Substantial | Moderate | Limited | Mixed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impaired memory to at least 7 days abstinence (heavy users) |

Depression (regular users) |

Impaired decision- making up to 2 days after last use (regular users) |

Impaired executive functioning after short abstinence |

| Acute psychotic symptoms during intoxication |

Gateway Drug |

Anxiety |

Cognitive impairment for at least 28 days after last use (heavy users) |

| Addiction risk | Psychosis | ||

| Lower lifetime achievement |

|||

| Motor Vehicle Accidents |

Clinical Use of Cannabinoids and Side Effects

A rigorously conducted meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of cannabinoids across a broad range of conditions found only 4 of 79 RCTs to have a low risk of bias 15, with 70% of studies having a high risk of bias, typically due to incomplete outcome data. The large majority of trials evaluated chemotherapy related nausea and vomiting, chronic pain and spasticity due to multiple sclerosis or paraplegia. Use of cannabinoids for chronic pain and spasticity was supported by moderate-quality evidence. Improvements in chemotherapy related nausea and vomiting, weight gain in HIV, sleep disorders and Tourette syndrome, was supported by low-quality evidence. Overall cannabinoids were associated with an increased risk of adverse effects, with an odds ratio (OR) of any adverse effect of 3.03 (95% CI: 2.42-3.80) and serious adverse effects, OR of 1.41 (95% CI: 1.04-1.92). There is a dearth of evidence related to clinical trials of cannabis itself, including associated adverse effects. As public acceptance of cannabis expands, some states have included in the legalization process that tax funds be allocated to address the lack of scientific knowledge on potential beneficial as well as harmful effects of use.

Mammalian endocannabinoid system

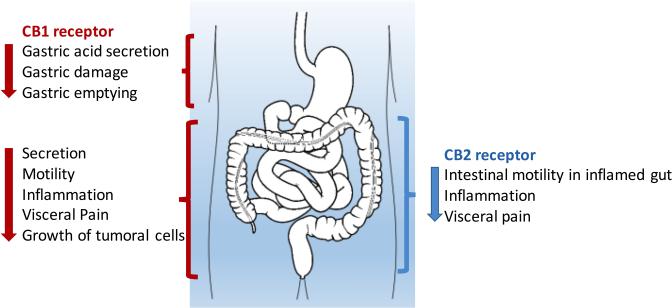

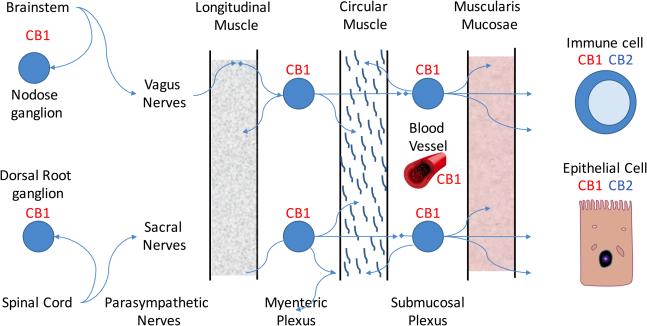

Cannabis affects humans through cross-reactivity with an endogenous mammalian cannabinoid sensing system known as the endocannabinoid system. This system includes receptors active in the central and peripheral nervous system (where they modulate appetite, pain, mood, and memory) as well as in many peripheral organs, including the gastrointestinal tract (where it may impact motility and secretion via acetylcholine) 16 (Fig1).

Figure 1.

Main effects of cannabinoid receptor CB1 and CB2 activation in the gastrointestinal tract. Adapted from 16

The most well-known receptors are the G-protein coupled cannabinoid-1(CB1) and cannabinoid-2 (CB2) receptors. The CB1 receptor expression is found primarily in the nervous system, while CB2 receptors may be found on immune cells where they modulate immune cell function. Additional atypical receptors, such as TRPV1 and GPR55 have been reported to be responsive to endocannabinoids, but their functions are still being clarified. The primary endogenous ligand for the CB1 receptor is anandamide, and the primary endogenous ligand for the CB2 receptor is 2- arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) 17. THC has greater affinity for the CB1 receptor than for the CB2 receptor and CBD has a weak affinity for CB2 receptor. Both anandamide and 2-AG are metabolized by the arachidonic acid pathway 16(Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Diagram of cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2 in the intestinal tract. Adapted from 16

What is in cannabis?

The cannabis plant is comprised of stem, leaves, nodes, and male or female flowers. The male cannabis flowers pollinate the female plants, while female flowers provide the cannabinoids for consumption. There are over 106 known phytocannabinoid chemicals identified from the cannabis plant 18. The two main active ingredients of cannabis are tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive substance, and cannabidiol (CBD), a largely non-psychoactive substance. Not only may plant products be present, but pesticides and fungi sometimes are found as well 19.

Depending on whether there are buds, leaves, and stems, the amount of THC, CBD, and other chemical components varies greatly. Many strains for recreational use have an abundance of THC, which induces both psychoactive and soporific effects, while CBD abundant strains such as Charlotte’s Web are less common, but gaining popularity due to the anti-seizure, anxiolytic, non-psychotropic effects. Epidiolex, a liquid formulation from GW Pharmaceuticals that contains pure, plant-derived CBD has received Fast Track designation from the Food and Drug Administration due to its very promising investigation trial in Dravet syndrome, a severe, refractory, infantile-onset form of epilepsy.

Pediatric IBD patients use cannabis

Patients and parents ask our opinion about trying cannabis for their IBD symptoms. From surveys we have conducted, we know that some of our patients in the pediatric IBD center at Children’s Hospital Colorado use cannabis 20. They report to us trying cannabis in multiple forms, including smoking, edibles, and CBD oil. Patients and parents tell us they feel it helps treat their IBD beyond improved coping, decreased pain, and better appetite. Furthermore, patients have asked us for a medical marijuana card, however, none in our group have completed a Physician Certification form required to formally recommend medical marijuana 3.

It seems logical that as care providers for children and adolescents with IBD, we should seek to know more about the medical effects of cannabis. Questions include: Is it really beneficial? What are the risks? How should we evaluate special considerations in IBD? Do our IBD patients use cannabis differently than those who use it for recreational use? Are IBD patients at greater risk for addiction (i.e. combined use with narcotics after surgery or for chronic pain)? What impact does intestinal inflammation or dysmotility have on absorption of edibles? And how do the chemicals in cannabis affect other medications used to treat IBD?

Do our IBD patients use cannabis similarly to peers without chronic illness?

Given our IBD patient’s interest in and use of legal medical and recreational cannabis in Colorado, we conducted a pilot study to measure use in 65 pediatric IBD subjects and 100 subjects without chronic illness 20. Using the validated CIDI-SAM questionnaire, 21 we found that frequency of ever using cannabis was similar between the groups (IBD 31% and control 40%, p= NS). However, IBD users reported weekly or more use much more frequently (IBD 55% and control 26%, OR 3.54 95% CI 1.14-11.05, p=0.03). Motivation for use was also different; the IBD group reported cannabis use more frequently for treatment of physical symptoms.

How do our results compare to state and national data? The Healthy Kids Colorado Survey (HKCS) 22 and the Youth Risk Behavioral Survey (YRBS) 23 provide this information. In 2013, both Colorado and National data show that about 40% of high school students had ever used cannabis, similar to our IBD and control groups. In terms of intensity of use, the HKCS and YRBS report about 20-25% use weekly or more. Again, our study’s comparison group, at 26%, was consistent with these data, while our IBD group, at 55%, was much higher. There are alarming national data 24 that daily or almost daily use of cannabis among 12-17yr olds is increasing rapidly. In 2003, 4.9M Americans 12 years and older reported daily cannabis use for the past month; by 2013 it was 8.1M.

We can summarize U.S. trends for cannabis use:

increase in daily use

increase in potency

continued and growing popular belief in the safety and possible benefits of regular consumption

pediatric IBD patients who use cannabis may do so more intensely and for physical reasons, compared to peers without chronic illness.

Cannabis for treatment of IBD

We could identify no studies evaluating cannabis for the treatment of IBD in children and data in adults are limited. There are 3 observational studies of about 300 adult subjects which suggest that use of cannabis is associated with subjective relief of symptoms 25,26,27.

A single placebo-controlled clinical trial of THC was conducted for treatment of Crohn’s disease. Patients smoked cigarettes with known THC content or placebo, and at 8 weeks, 10 of 11 in the cannabis group showed a response with a drop in CDAI, compared to 4 of 10 in the placebo group (p = 0.028) 28. Whether there is a disease modifying benefit, as opposed to an enhanced quality of life is unknown. And whether the effect is long lasting has also not been studied.

Potential beneficial mechanisms of cannabis in IBD

Cannabis can potentially be used to alleviate a number of IBD-associated intestinal symptoms, including reducing nausea, stool frequency and abdominal pain, while improving appetite and weight gain29,7, 30. This in turn may indirectly influence intestinal inflammation and possibly microbiome. However, it remains unclear whether or not it has any direct impact on the underlying disease pathogenesis. We do know that the endogenous cannabinoid system (including cannabinoid receptors and the cognate ligand anandamide) is up-regulated in ulcerative colitis patients 31, 32 suggesting a role in disease regulation. Moreover, anandamide has been shown to suppress proliferation and cytokine release from primary human T-lymphocytes mainly via the CB2 receptor 33. CBD may exert anti-inflammatory effects through inhibition of fatty acid amidohydrolase (FAAH), which leads to increased concentrations of anandamide 34.

The primary psychoactive ingredient in cannabis, THC, acts mainly as a weak CB1 receptor agonist. Through this pathway, THC can also inhibit human T cell proliferation, preferentially targeting the same pro-inflammatory IFNγ-producing Th1 cells that are heavily implicated in IBD pathogenesis 35,36. However, THC also increases the concentration of regulatory T cell-associated cytokines, IL-10 and TGFβ, in unfractionated human T cell cultures 37,38 suggesting that the capacity of THC to reduce T cell proliferation may actually reflect the ability to enhance regulatory T cell suppressive function. This could be particularly beneficial in the context of IBD given the established impaired regulatory T cell suppressive function associated with this disease 39. One concern with the administration of cannabinoids in the context of inflammation and increased endocannabinoid production is the potential for receptor desensitization which can occur in the case of the human immune-associated CB2 receptor 40. While anandamide and THC might both have beneficial effects in isolated short-term cell culture experiments, it remains to be seen if the chronic combination has synergistic or contradictory effects in vivo.

In addition to potential T cell targeted anti-inflammatory mechanisms, cannabinoids have also been shown to impair cytokine production by human neutrophils, and in particular the IBD-associated pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα 41. Human neutrophil transmigration in vitro is also impaired by treatment with a synthetic cannabinomimetics, although the mechanism, while unclear, does not appear to be mediated via the CB1 or CB2 receptor suggesting that it may have been an indirect effect. While neutrophils are relatively short-lived, they are widely considered to be critical to the acute phase of intestinal injury associated with IBD.

Clearly, our overall understanding of potential anti-inflammatory mechanisms of cannabis is relatively poor. This is compounded by the wide array of biologically active components found in cannabis which include agonists, antagonists, partial agonists, positive allosteric modulators and negative allosteric modulators. A clinical trial sponsored by Bial, a pharmaceutical company in Portugal, and conducted by the French company Biotrial, studied the effect in human volunteers of a fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) inhibitor, an enzyme that is thought to break down endocannabinoids in the brain. The study was aborted after 5 of 6 subjects receiving the highest doses developed significant neurologic side effects including one death 42. While this effect was not believed to be a drug class effect, it highlights that further study is essential to determine the possible impact and safety of cannabinoids prior to their use for the treatment of IBD.

Challenges with cannabis in human subject research

With the legalization of medical and recreational cannabis and implementation of a regulatory system, one would expect that this recent change to the law would open new opportunities for human subject research involving cannabis. In fact, we have obtained a grant from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment to perform an observational study to evaluate cannabis in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. However, academic researchers in Colorado now face some paradoxical challenges because under federal law, cannabis continues to remain a Schedule 1 drug.

To start with, there is still some uncertainty about the future of legalized cannabis in Colorado. On August 29th, 2013, the Department of Justice released an update to the Marijuana Enforcement Policy 43, restating its efforts on enforcement priorities related to cannabis and the Department’s expectation that States that legalize cannabis would establish strict regulatory schemes that protect these federal enforcement priorities. This policy was based on assurance from the Colorado governor that these schemes will be in strict adherence and include strong state-based enforcement efforts that are backed by adequate funding. But the Department of Justice clearly states that it reserves the right to challenge the State’s legalization in the future.

There is also a continuing risk to be involved in litigation. Throughout 2015, several Colorado private businessmen operating cannabis businesses that were authorized under State law, as well as businesses that financed, insured, built and funded these businesses, were sued under the allegation that they constitute criminal enterprises under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization (RICO) Act 44.

Furthermore, a careful review of funding sources for research involving cannabis is critical because the Controlled Substances Act and other laws, such as the Anti-Money Laundering (AML) law, prohibit everyone from dealing with the proceeds from Controlled Substances, or from engaging in financial transactions with these proceeds.

For universities receiving Title IV federal student aid funding, the Drug Free Schools and Campuses Regulations (EDGAR Part 86) require the implementation of a program to prevent the unlawful possession, use or distribution of illicit drugs and alcohol by students and employees, and a policy that stipulates that a student or employee who violates the alcohol and other drugs policy is subject to both the institution’s sanction and to criminal sanctions provided by federal, state and local law. This again creates a challenging environment for academic researchers who want to study health effects of cannabis.

Researchers who plan to conduct a scientifically designed, interventional study with cannabis have additional challenges. First, in the United States, NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse) the federal agency overseeing marijuana for human subject research, contracts with the University of Mississippi to grow the only current supply of marijuana for use in human research studies 45. Second, even when following and completing all required regulatory steps for this research, including investigational new drug application (IND) from Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) researcher registration, institutional review board (IRB) approval, the Colorado State Board of Pharmacy does not allow any involvement of hospital pharmacists in research with cannabis, and the research cannot be performed under the hospital’s DEA license. Hence implementation of scientifically designed, interventional research requires the development of new processes, including new drug storage and dispensing processes, to conduct the research in a manner that is compliant with all applicable laws and policies. Lastly, many observational studies would benefit from having a quantitative analysis of the various cannabinoids in the product(s) used by the end users. Due to the challenges listed above, academic researchers are not allowed to have patients bring their cannabis products on campus for chemical analysis, and the state certified laboratories only perform testing for licensed cannabis growers.

Given all of the above challenges, our institution developed still evolving guidelines for human subject research involving cannabis (Table 3). We also identified a number of important issues that have yet to be resolved (Table 4). We recommend ongoing monitoring of federal and state laws as the field evolves.

Table 3.

University of Colorado School of Medicine guidelines for human subject research involving cannabis (marijuana) as of February 2016

| For all studies: |

| Cannot accept funding for research from cannabis industry |

| For observational studies: |

| Can survey or evaluate subjects who are already using drug for medical or recreational purposes (e.g. can ask subject to come in for a blood draw 1 hour after taking drug) |

| Should obtain federal Certificate of Confidentiality for the study |

| Cannot subsidize the purchase of the cannabis products |

| Cannot pay subjects to participate in the study |

| Cannot bring to campus cannabis products to test level of cannabinoids (e.g. from grower or retailer) |

| Cannot advise or prescribe to start taking the drug, or manage it in any way. |

| Cannot dictate when the drug is to be given (e.g. specific times to enable pharmacokinetic studies) |

| Cannot ask users to stop cannabis use to be eligible to participate in a study (e.g. no baseline studies) |

| Cannot ask to stop using drug for a washout period |

| Cannot have subjects smoke or ingest drug anywhere on campus prior to being interviewed or evaluated for research |

| Cannot advise or prescribe to start taking the drug |

| Cannot move people higher on waiting list for a certain product at the dispensary if they agree to participate in a study |

| For interventional studies (including animal studies): |

| Must be conducted under an IND from the FDA |

| Can only use cannabis purchased from NIDA or a cannabis-derived product that has an FDA record (FDA approved, or under IND) |

| Must apply for a DEA Researcher registration |

| Cannot add marijuana to clinical DEA license |

| Must use specifically designed and dedicated locations for storage and administration of the drug |

| Must post study on ClinicalTrials.gov posting as Applicable Clinical Trial. Study results need to be posted no later than 12 months after the final collection of the primary outcome data |

Table 4.

Issues on cannabis research that have been identified but are yet to be resolved

| Should observational studies that include minors be limited to those with medical marijuana license? Should clinical researchers obtain a copy of the medical marijuana license? |

| How close are the chemical concentrations and ratios from an individual cannabis sample to those in the grower’s profile for the harvest batch? Can researchers rely on the profile values? If not, how can they obtain quick and inexpensive chemical analyses done without violating any regulations and policies? |

| How can clinical researchers get continuous pre- and post-administration pharmacokinetic data without violating any regulations and policies? |

| Even if listed as caregiver of a minor child, what might be the risk to parents who give cannabis or cannabis-derived products to their child? |

Conclusion

Use of recreational and medical cannabis use is increasing in the United States. There is an incorrect public perception of the safety of regular use. Approximately 30-40% of adolescents and young adults with IBD will try cannabis and some report benefit for their IBD. There is some rationale for considering a possible immune modifying effect of cannabis on IBD. The possible benefits and significant risks need to be better understood. However, the current regulatory environment imposes unique challenges on performing rigorous research into cannabis use. Care providers should become familiar with the issues around cannabis use and maintain open communication with their pediatric IBD patients.

What is known on this subject.

Cannabis use is increasingly accepted across the United States.

There is public perception of the medical benefits of cannabis to treat many chronic diseases including IBD, but little concern about safety.

What this study adds

Approximately one quarter of adolescents and young adults with IBD in Colorado use cannabis regularly.

Although there is rationale for considering that cannabis might be helpful, there are unique aspects to conducting research on cannabis in pediatric IBD patients.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure statement:

Edward Hoffenberg has a grant from Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment to study the benefits of marijuana in pediatric and adolescent IBD

Colm Collins: supported by funding from NIH NIDDK K01

Funding source: none

Abbreviations

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- CBD

cannabidiol

- THC

tetrahydrocannabinol

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: the authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Note: term cannabis used primarily, but marijuana used when referring to state or federal programs using the term

Contributor Information

Edward J. Hoffenberg, Department of Pediatrics, Digestive Health Institute, University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine.

Heike Newman, Department of Regulatory Compliance, University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine 12631 E 17th Ave, Aurora CO 80045. heike.newman@ucdenver.edu.

Colm Collins, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine, Mucosal Inflammation Program. colm.collins@ucdenver.edu

Kristina Leinwand, Department of Pediatrics, Digestive Health Institute, University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine. kristina.leinwand@childrenscolorado.org

Sally Tarbell, Department of Psychiatry, University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine. sally.tarbell@childrenscolorado.org.

References

- 1.Money C. Where pot is legal. CNN Money. 2015;2015 Cable News Network. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Secretary of State of Colorado Medical Use of Marijuana. Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, Health and Environmental Information and Statistics Division. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.>Colorado Department of Public Health and E. Physician Certification. MMR1002. Colorado Medical Marijuana Registry. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rocky Mountain High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (RMHIDTA) Youth and Adult Marijuana Use. 2016:13. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baca R. Denver Post. Denver Post; Denver: 2016. Colorado marijuana sales skyrocket to more than $996 million in 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young S. Medical Marijuana Refugees: 'This was our only hope'. CNN Health + 2014;2016 U.S. Edition ed: Cable News Network. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerich ME, Isfort RW, Brimhall B, Siegel CA. Medical Marijuana for Digestive Disorders: High Time to Prescribe? Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston L, O'Malley P, Miech R, Bachman J, Schulenberg J. Monitoring the Future: National Survey Results on Drug Use 1975-2013 Overview, Key findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Institute for Social Research; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor: 2014. p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SR. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2219–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rocky Mountain High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (RMHIDTA) Center RMHIDTA Investigative Support Center. Vol. 2. Denver: 2014. The Legalization of Marijuana in Colorado The Impact. [Google Scholar]

- 11.ElSohly M. Vol. 123. National Center for Natural Products Research; University of Mississippi: 2014. Potency Monitoring Program quarterly report no. 123-reporting period: 9/16/2013-12/15/2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simonetto DA, Oxentenko AS, Herman ML, Szostek JH. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: a case series of 98 patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:114–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AAP Committee on Substance Abuse and AAP Committee on Adolescence The impact of marijuana policies on youth: clinical, research, and legal update. Pediatrics. 2015;135:584–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-4146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.AACAP Committee on Substance Abuse and Committee on Adolescence AACAP Marijuana Legalization Policy Statement: American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, Di Nisio M, Duffy S, Hernandez AV, Keurentjes JC, Lang S, Misso K, Ryder S, Schmidlkofer S, Westwood M, Kleijnen J. Cannabinoids for Medical Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313:2456–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Izzo AA, Camilleri M. Emerging role of cannabinoids in gastrointestinal and liver diseases: basic and clinical aspects. Gut. 2008;57:1140–55. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.148791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massa F, Storr M, Lutz B. The endocannabinoid system in the physiology and pathophysiology of the gastrointestinal tract. J Mol Med (Berl) 2005;83:944–54. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0698-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huestis MA. Human cannabinoid pharmacokinetics. Chem Biodivers. 2007;4:1770–804. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baca R, Migoya D. Denver Post. Denver Post; Denver: 2015. Marijuana products pulled in Denver in largest pesticide recalls. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffenberg A, Hopfer C, Markson J, Garling T, Guerrero-Baez J, Hoffenberg E. Marijuana use in Adolescents and Young Adults with and without Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57 e 64 #227. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cottler LB. Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Substance Abuse Module (SAM) Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gruber K, Anderson A, Calanan R, VanDyke M, Barker L, Burris D, Tolliver R. Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. March Denver; 2015. Marijuana Use Among Adolescents in Colorado: Results from the 2013 Healthy Kids Colorado Survey; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance-United States, 2013. MMWR. 2014;63:172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2014. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lal S, Prasad N, Ryan M, Tangri S, Silverberg MS, Gordon A, Steinhart H. Cannabis use amongst patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:891–6. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328349bb4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ravikoff Allegretti J, Courtwright A, Lucci M, Korzenik JR, Levine J. Marijuana use patterns among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2809–14. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000435851.94391.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Storr M, Devlin S, Kaplan GG, Panaccione R, Andrews CN. Cannabis use provides symptom relief in patients with inflammatory bowel disease but is associated with worse disease prognosis in patients with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:472–80. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000440982.79036.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naftali T, Bar-Lev Schleider L, Dotan I, Lansky EP, Sklerovsky Benjaminov F, Konikoff FM. Cannabis induces a clinical response in patients with Crohn's disease: a prospective placebo-controlled study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1276–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.04.034. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dejesus E, Rodwick BM, Bowers D, Cohen CJ, Pearce D. Use of Dronabinol Improves Appetite and Reverses Weight Loss in HIV/AIDS-Infected Patients. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2007;6:95–100. doi: 10.1177/1545109707300157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schicho R, Storr M. IBD: Patients with IBD find symptom relief in the Cannabis field. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:142–3. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marquez L, Suarez J, Iglesias M, Bermudez-Silva FJ, Rodriguez de Fonseca F, Andreu M. Ulcerative colitis induces changes on the expression of the endocannabinoid system in the human colonic tissue. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D'Argenio G, Valenti M, Scaglione G, Cosenza V, Sorrentini I, Di Marzo V. Up-regulation of anandamide levels as an endogenous mechanism and a pharmacological strategy to limit colon inflammation. FASEB J. 2006;20:568–70. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4943fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cencioni MT, Chiurchiu V, Catanzaro G, Borsellino G, Bernardi G, Battistini L, Maccarrone M. Anandamide suppresses proliferation and cytokine release from primary human T-lymphocytes mainly via CB2 receptors. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burstein SH, Zurier RB. Cannabinoids, endocannabinoids, and related analogs in inflammation. AAPS J. 2009;11:109–19. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCulloch C, Searle S, Neuhaus J. Generalized, linear, and mixed models. John Wiley and Sons. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strober W, Fuss IJ. Proinflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1756–67. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wittchen HU. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO--Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28:57–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pacifici R, Zuccaro P, Pichini S, Roset PN, Poudevida S, Farre M, Segura J, De la Torre R. Modulation of the immune system in cannabis users. JAMA. 2003;289:1929–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.15.1929-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boschetti G, Nancey S, Sardi F, Roblin X, Flourie B, Kaiserlian D. Therapy with anti-TNFalpha antibody enhances number and function of Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:160–70. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shoemaker JL, Joseph BK, Ruckle MB, Mayeux PR, Prather PL. The endocannabinoid noladin ether acts as a full agonist at human CB2 cannabinoid receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:868–75. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.085282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kusher DI, Dawson LO, Taylor AC, Djeu JY. Effect of the psychoactive metabolite of marijuana, delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), on the synthesis of tumor necrosis factor by human large granular lymphocytes. Cell Immunol. 1994;154:99–108. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Enserik M. Science News. Vol. 2016. American Academy for the Advancement of Science; New York: 2016. More details emerge on fateful French drug trial. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cole JM. Department of Justice. Office of the Deputy Attorney General; Washington, DC: 2013. Guidance Regarding Marijuana Enforcement. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cole JM. Department of Justice. Office of the Deputy Attorney General; Washington, DC: 2014. Guideline Regarding Marijuana Related Financial Crimes. [Google Scholar]

- 45.US Food and Drug Administration . Marijuana Research with Human Subjects. Vol. 2016. U.S. FDA; Washington, D.C.: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Secretary of State, State of Colorado . Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. Vol. 5. Secretary of State; Colorado: 2015. Medical Use of Marijuana. CCR 1006-2. [Google Scholar]

- 47.The Retail Marijuana Public Health Advisory Committee . Changes in marijuana use patterns, systematic literature review, and possible marijuana-related health effects. Colorado State Board of Health; Denver: 2015. Monitoring Health Concerns Related to Marijuana in Colorado: 2014. [Google Scholar]