Abstract

The circulating antibody repertoire encodes a patient's health status and pathogen exposure history, but identifying antibodies with diagnostic potential usually requires knowledge of the antigen(s). We previously circumvented this problem by screening libraries of bead-displayed small molecules against case and control serum samples to discover “epitope surrogates” (ligands of IgGs enriched in the case sample). Here, we describe an improved version of this technology that employs DNA-encoded libraries and high-throughput FACS-based screening to discover epitope surrogates that differentiate noninfectious/latent (LTB) patients from infectious/active TB (ATB) patients, which is imperative for proper treatment selection and antibiotic stewardship. Normal control/LTB (10 patients each, NCL) and ATB (10 patients) serum pools were screened against a library (5 × 106 beads, 448k unique compounds) using fluorescent anti-human IgG to label hit compound beads for FACS. Deep sequencing decoded all hit structures and each hit's occurrence frequencies. ATB hits were pruned of NCL hits and prioritized for resynthesis based on occurrence and homology. Several structurally homologous families were identified and 16/21 resynthesized representative hits validated as selective ligands of ATB serum IgGs (p < 0.005). The native secreted TB protein Ag85B (though not the E. coli recombinant form) competed with one of the validated ligands for binding to antibodies, suggesting that it mimics a native Ag85B epitope. The use of DNA-encoded libraries and FACS-based screening in epitope surrogate discovery reveals thousands of potential hit structures. Distilling this list down to several consensus chemical structures yielded a diagnostic panel for ATB composed of thermally stable and economically produced small molecule ligands in place of protein antigens.

The detection of specific IgG populations in the circulating repertoire forms the basis of numerous immunological diagnostics such as the ELISA, however, the discovery of IgGs with diagnostic potential usually follows identification of their cognate antigens. The complexity of this task grows as the number of potential antigens increases from a relatively small immunoproteome (e.g. HIV) to the much larger spaces of pathogenic bacteria or the human proteome. Further, many diseases occur in multiple clinically distinct states, such as viral or bacterial latency, requiring a dissection of antigen identity, IgG response, and clinical manifestation.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection can result in a spectrum of infection phases and a major priority of the World Health Organization1 is to differentiate between active TB disease and subclinical (latent) infection. The latent, noninfectious state (LTB) is defined by granulomatous lesions that encase the pathogen. In the active and infectious state (ATB), rapidly dividing bacilli invade pulmonary and other tissues, are able to overcome protective immune responses, and eventually cause symptoms. Neither current point-of-care tests (tuberculin skin test) nor more advanced assays (interferon gamma release, PCR) can differentiate status. The stark differences between the pathogen's LTB and ATB metabolic states suggest that the host immunological response may provide the most discriminatory signals2. Protein microarray data point to a small collection of candidate antigens — mostly comprising membrane-associated and secreted proteins (e.g. ESAT-6, CFP-10, Ag85)3 — that could generate the desired differential response. Extensive investigations of these and other antigens' suitability as TB serological diagnostics have ensued, however, no single antigen yields appropriate diagnostic sensitivity and specificity4. Furthermore, ongoing studies increasingly highlight the importance and prevalence of TB-specific post-translational modifications (PTMs) particularly on secreted antigens5, ultimately necessitating mycobacterial antigen production and thereby raising scale-up and stability challenges for diagnostic development. Serial native antigen evaluation thus poses a daunting combinatorial and logistical challenge.

It is possible to circumvent both up-front antigen selection biases and production bottlenecks by combinatorially querying IgG repertoires corresponding to known patient statuses. Differentially probing a protein microarray6 that displayed a rich sampling of the Mtb proteome led to an experimental definition of its immunoproteome, the subset of Mtb immunodominant proteins3. Phage display epitope libraries can be used to pan IgG repertoires for peptide antigen mimetics (“mimotopes”)7 in many disease contexts, including the identification of antigenic proteins in TB8,9. However, peptides are susceptible to proteolytic degradation and costly to produce at scale. Recently we have shown that combinatorial libraries of N-substituted oligoglycines (“peptoids”)10 and other non-natural oligomers can source IgG ligands (“epitope surrogates”) specific for Alzheimer's disease11, neuromyelitis optica12, chronic lymphocytic leukemia13, and type 1 diabetes (T1D)14. Epitope surrogates can serve as affinity reagents for selective purification of the disease-specific IgGs and subsequent native antigen identification. For example, an epitope surrogate discovered from a screen of T1D patient sera ultimately identified peripherin as a major T1D autoantigen15. The T1D-specific antibodies recognize only a highly phosphorylated, dimeric form of the protein, suggesting that native antigens of the disease-specific antibodies are unlikely to be “vanilla” peptides or recombinantly-expressed proteins. Synthetic epitope surrogates not only serendipitously mimic chemical functionality beyond the space of the 20 biogenic amino acids, but are potentially advantageous for diagnostics because they resist proteolytic degradation16, are economically synthesized17, and do not require refrigeration — all qualities of diagnostics that are amenable to resource-limited and point-of-care settings.

The discovery of epitope surrogates from combinatorial libraries of synthetic molecules is currently a manual and tedious process. A one-bead-one-compound (OBOC) library of molecules (i.e., each bead displays many copies of a single molecule) displayed on 90-μm TentaGel beads is incubated in control sera, beads displaying compounds that bind to control antibodies are visualized with a fluorescent anti-IgG secondary antibody, and manually removed. The remaining library is incubated in case serum and the process is repeated to isolate putative ligands to antibodies unique to, or highly enriched in, the case. The chemical structure of the hit ligands is then elucidated by mass spectrometry (MS) one bead at a time. Due to the low throughput of manual bead picking and MS structure elucidation, it is not feasible to build consensus structures as in phage display, where next-generation sequencing (NGS) -based analysis can now detail the phylogenetic history of an antigen's discovery18.

DNA-encoded small molecule libraries (DELs) have provided an elegant approach to marrying the power of genetic information storage and retrieval with access to diverse chemotypes via chemical synthesis. Encoded combinatorial synthesis entails coupling a nucleic acid encoding step with each chemical synthesis step19,20, and after selection-type separation of target ligands, NGS analysis20,21 can be used to decode the structures of all hits. Potent ligands have resulted from DEL selections against a variety of purified targets22–24, but it stands to reason that such combinatorial libraries could be even more useful in a phenotypic assay, where the target identity is unknown. Here, we demonstrate the use of DNA-encoded combinatorial libraries of non-natural oligomers for unbiased IgG repertoire screening, and NGS analysis to discover statistically significantly represented hit structures and structurally homologous families of ATB-specific epitope surrogates.

Results

Library synthesis

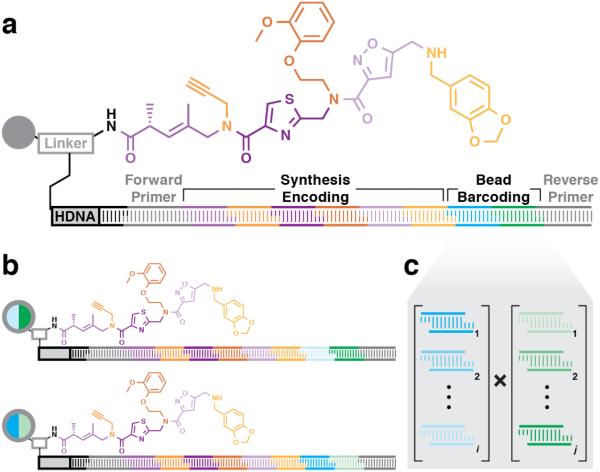

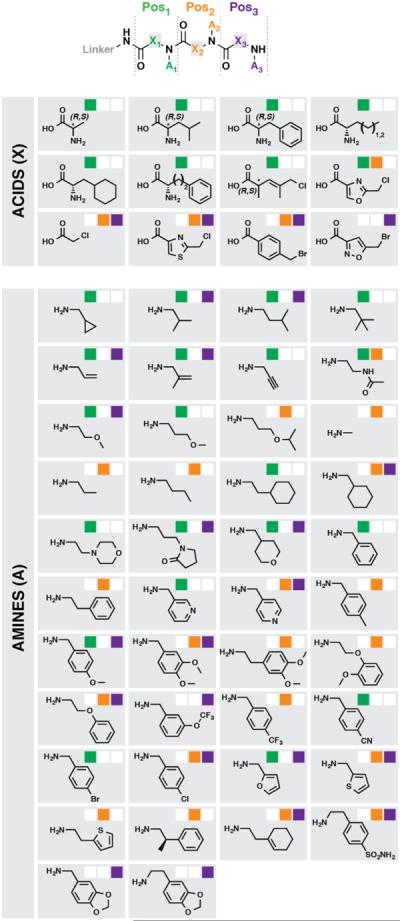

A solid-phase DNA-encoded combinatorial library was synthesized as described previously using peptide couplings and the sub-monomer method employed to construct peptoids and similar compounds25. The 448k-member library (Fig. 1) featured diversity at three positions (Pos1, Pos2, Pos3) in both the main chain scaffolding and side chains using a variety of building block (BB) types. Pos1 contained a collection of amino acids (both stereochemical configurations) and diverse submonomer-type BBs (haloacids and amines for halide displacement)17,26,27. Pos2 and Pos3 contained only submonomer-type BBs. The library was synthesized on a dual-scale mixture of 10-μm screening beads and 160-μm quality control (QC) beads, the latter doped at a low level (QC:screening = 1:30,000). After synthesis, the QC beads were harvested, the DNA-encoding tags of single QC beads were amplified, sequenced, and decoded to yield the bead's synthesis history and predicted compound structure. MALDI-TOF MS analysis of the corresponding resin-cleaved compound was then compared to the encoding-predicted structure mass. The spectra of 19/20 QC bead compounds were consistent with the DNA-encoded structures, which collectively contained at least one instance of 34/60 BBs used for library synthesis.

Figure 1. DNA-encoded combinatorial library plan.

The library synthesis reaction sequence consisted of three acylations, enumerated as diversification positions Pos1 (green), Pos2 (orange), and Pos3 (purple). The BB set included carboxylic acids (Xi, amino acids and haloacids) for diversifying the main chain scaffold and amines (Ai) for diversifying the intervening amide via displacement of the haloacids. Pos1 diversity included 10 amino acids, 3 haloacids, and 20 amines. Pos2 and Pos3 diversity included 4 haloacids and 20 amines. If a BB was used at a given position, its indicator (upper right) is filled with the appropriate color.

FACS-based high-throughput screening

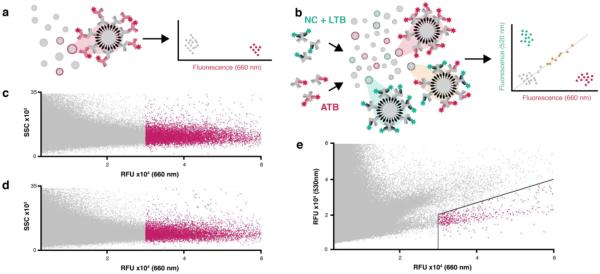

ATB-selective serum IgG-binding ligands were identified using FACS-based high-throughput screening. Both single-color and two-color strategies were explored (Fig. 2a,b). The one-color screens were performed by incubating ~10 copies of the library (~5 × 106 beads) with pooled serum samples acquired from 10 ATB patients. Another ~10 copies were incubated with a mixture of sera acquired from 10 LTB patients and 10 TB negative control (NC) individuals who had not been previously exposed to Mtb as determined by Quantiferon TBGold test, comprising the “NCL” pool. After washing, the beads were incubated with a secondary detection IgG (Alexa Fluor 647 anti-human IgG) to label serum IgG-binding hit compound beads for collection by FACS. The screen yielded 6297 ATB hit beads and 8579 NCL hit beads (Fig. 2c,d). A control screen for library beads that bind the secondary detection IgG in the absence of serum was also performed, yielding 447 beads.

Figure 2. Serum IgG binding assay schematic and FACS-based high-throughput screening data.

(a) In single-color screens, library beads are incubated with serum-containing IgGs (gray IgGs), some of which bind specific beads. Probing with Alexa Fluor 647 anti-human IgG conjugate (red IgG, λem = 660 nm) labels serum IgG-bound beads for collection in FACS. (b) In two-color screens, serum pools are pre-labeled with anti-human mFab. The NCL pool is labeled with anti-human mFab488 (green Fab, λem = 530 nm), the ATB pool is labeled with anti-human mFab647 (red Fab, λem = 660 nm), and the pools are mixed. Probing the library with this mixed serum generates three populations of IgG-bound beads in multiplexed FACS analysis: NCL-specific IgG binding correlates with 530-nm fluorescence (upper left quadrant), ATB-specific IgG binding correlates with 660-nm fluorescence (lower right quadrant), and non-specific IgG and mFAB binding correlates with both channels (diagonal). FACS analysis of a single-color of pooled NCL serum screen (c) and pooled ATB serum screen (d) was gated for collection of hits > 30,000 RFU (λem = 660 nm, red). Side scatter (SSC) was used to gate single beads. Two-color FACS analysis of a mixed, pre-labelled NCL/ATB serum pool screen (e) wastwo-dimensionally gated (black lines) for hit collection (red).

The same ATB and NCL serum pools were used for a two-color screen. Addition of a secondary detection mFab (Alexa Fluor 488 anti-human mFab, mFab488) to the NCL serum labeled the NCL IgGs in one color while addition of a differently labeled secondary detection mFab (Alexa Fluor 647 anti-human mFab, mFab647) to the ATB serum labeled ATB IgGs with the second color. The pre-labeled sera were mixed and incubated with DNA encoded library beads (5 × 106). Beads with high 660-nm fluorescence (ATB serum) and low 530-nm fluorescence (NCL serum) were isolated by FACS (723 beads, Fig. 2e). The hit bead collection DNA-encoding tags of each screen were separately amplified, sequenced, and decoded to generate lists of candidate NCL and ATB IgG ligands.

Encoding tag analysis and pan-library structure-activity relationship profile

NGS analysis of the hit bead collection amplicons generated lists of hit sequences for decoding based on a modified encoding tag structure (Fig. 3a). The synthesis encoding tag structure was expanded to accommodate 8 encoding regions, the first 6 positions used to encode chemical synthesis and the final 2 used to assign bead-specific barcodes (Supplementary Table T1). Bead-specific barcodes were used to differentiate redundant hits (i.e. identical compounds observed as hits on different beads, Fig. 3b) and tabulate hit occurrence frequency for each screen. The four TB screens (single-color secondary detection IgG only, single-color ATB, single-color NCL, and two-color ATB/NCL) generated 2086 unique encoding sequences. Single-color data were pruned of all synthesis encoding sequences that occurred with only one bead-specific barcode, after which 792 ATB hit sequences remained. All hit sequences that also appeared in the secondary detection IgG only and NCL single-color screens were eliminated, leaving 351 ATB hit sequences. The two-color screen, which internally controlled NCL and non-specific IgG binding, generated 88 unique synthesis encoding sequences that occurred with more than one bead-specific barcode, 85 of which did not appear in either the secondary detection IgG only or NCL single-color screens. Of the reduced ATB single-color and two-color hit sequence sets, 36 occurred in both screening modes.

Figure 3. DNA-encoded solid-phase synthesis and bead-specific barcoding.

(a) The DNA-encoded solid-phase synthesis bifunctional resin linker displays amine sites for compound synthesis and DNA headpiece sites (HDNA, a tether that covalently joins the two DNA strands) for enzymatic ligation of encoding oligonucleotides. The encoding tag contains a synthesis encoding region and bead barcoding region flanked by forward and reverse primer binding modules (gray). After ligation of the forward primer sequence, each monomer coupling step accompanies an enzymatic cohesive end ligation that installs a dsDNA encoding module. A submonomer approach includes various main chain scaffold structures (purple) and amine side chains (orange). Corresponding encoding modules appear in the same color. After encoded synthesis, ligation of two additional encoding modules assigns a bead-specific barcode, and reverse primer ligation completes the encoding tag. (b) Bead-specific barcodes distinguish beads that harbor identical compounds, which would otherwise display identical DNA sequences. (c) Combinatorial ligation of i sequence modules in the first bead-specific barcoding position (cyan hues) and j sequence modules in the second position (green hues) yields i × j possible unique bead-specific barcodes.

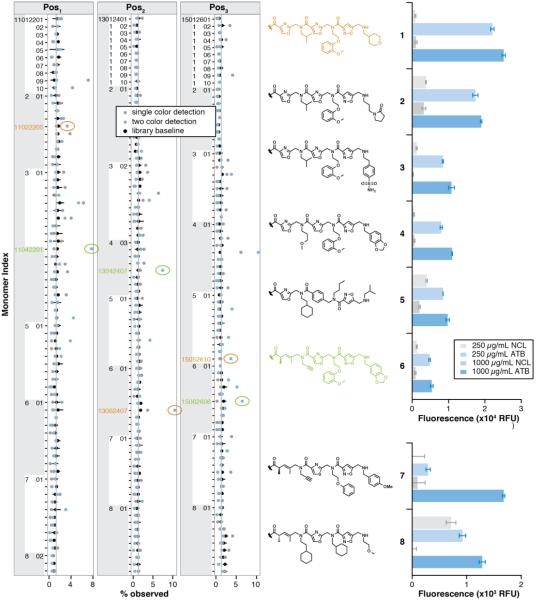

The relative occurrence of each monomer in the one- and two-color ATB hit sequence pool in conjunction with the hit occurrence frequency derived from bead-specific barcodes guided the selection of hits for resynthesis. The pan-library structure-activity relationship data, shown as a plot of the position-dependent occurrence frequency of each monomer (% observed) in comparison with its occurrence frequency in a random sample of the library (Fig. 4, left), illuminated highly enriched structural features of each screening hit collection. In addition to this “bottom-up” analysis of structure conservation among hits, a “top-down” census of hits that occurred with the highest frequency between both screening pools was also conducted. Of the 36 hit sequences observed in both ATB screens, 27 were observed ≥ 5 times and the top 10 hits were observed ≥ 8 times (Supplementary Table T2). Hit sequences that occurred with high frequency and contained more frequently observed monomers were prioritized for resynthesis. This included 18 of the 36 hit sequences observed in both screening modes and 3 hit sequences derived from highly enriched monomers. The 21 representative hit sequences were clustered into four thematic synthesis histories: (1) heterocycle haloacid or 4-(bromomethyl)-benzoic acid BBs in all 3 positions, (2) heterocycle haloacid BBs in Pos2 and Pos3 with Pos3 N-(3-aminopropyl)-2-pyrrolidinone displacement, (3) either stereochemistry chloropentenoic acid BB in Pos1, and (4) pyridine-containing BBs in Pos1.

Figure 4. Pan-library structure-activity relationship profile and high-priority hit validation.

Left, the position-dependent occurrence frequency of each monomer structure (% observed) was plotted for decoded structures observed in the single-color screening hit collection (blue), two-color screening hit collection (cyan), and a random sample of the library (black). Library values are shown with the standard error of three random library samples and the gray line indicates the theoretical monomer frequency as calculated from the library plan. Several monomers occurred significantly more frequently in hit structures. The monomer index is the 8-digit sequence identifier that specifies the monomer structure and position. Center, high-priority exemplar hit structures 1 – 8 are shown with colored structures containing the identically colored high-frequency monomer indices. Right, 1 – 8 were purified, re-immobilized on beads, and their ATB serum IgG binding (blue bars) compared to NCL serum IgG binding (gray bars) at two serum concentrations (0.25 and 1 mg/mL; 0.25 mg/mL binding data are magnified 4 fold). All compounds statistically significantly bound more ATB serum IgG than NLC serum IgG (p = 0.005).

The encoded synthesis histories of the 21 representative hits were reproduced on a larger scale with a C-terminal cysteine. These products were purified and appended to resin via thioalkylation for validation using a Luminex-like assay previously developed in our laboratory28. Serum IgG binding assay results (Fig. 4, right) of 16/21 hit sequences indicated ATB-selective binding over NCL binding for at least one product at the screening serum concentration (1000 μg/mL, LOD > 3, p = 0.005) and 13/21 yielded at least one product that maintained ATB-selective binding at lower serum concentration (250 μg/mL, LOD > 3, p = 0.005). Reproducing the synthesis histories coding N-(3-aminopropyl)-2-pyrrolidinone in Pos3 (2, 9, 10, Supplementary Fig. S5, S12, S13) yielded both the expected product and a side product (2-A/B, 9-A, 10-A, Supplementary Fig. S5, S12, S13), both of which selectively bound ATB serum IgGs. NMR analysis of the isoxazole N-(3-aminopropyl)-2-pyrolidinone Pos3 monomer supports assignment of a side product structure that results from an acid-catalyzed cyclization and concomitant loss of water (Supplementary Fig. S25). Resynthesis of sequences coding for pyridine-containing Pos1 monomer (19, 20, Supplementary Fig. S22–S23) produced beads that were red and did not selectively bind ATB serum IgGs. These false positives were likely identified by FACS sorting due to their high intrinsic fluorescence. Resynthesis of all hit sequences with heterocycle haloacid or 4-(bromomethyl)-benzoic acid BBs in Pos1, Pos2 and Pos3 yielded the expected major product, and selectively bound ATB serum IgGs at both serum concentrations (0.25 and 1 mg/mL). The expected products of sequences coding for chloropentenoic acid BBs in Pos1 (6–8, 13–18, 21, Supplementary Fig. S9–S11, S14–S16, S19–S21 and S24) selectively bound ATB serum IgGs at [serum] = 1 mg/mL (7/10 hits) and [serum] = 0.25 mg/mL (4/10 hits).

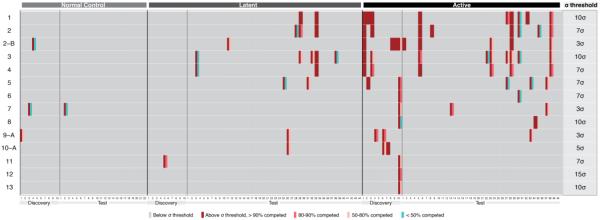

Patient-specific binding validation

Hit structures that validated with pooled serum samples used for library screening were next tested for binding to serum IgG repertoires of individual patients. (Fig. 5). The “discovery” patient sample set comprised those serum samples used for library screening (10 ATB, 10 LTB, 10 NC), and the “test” patient sample set comprised all other samples that were not used for library screening (40 ATB, 44 LTB, 11 NC). Competition binding with soluble ligand was then assayed for individuals that scored binding above the threshold. This competition experiment is critical because some serum samples contain antibodies that exhibit high non-specific adsorption. If less than 50% of the original signal is competed by excess soluble molecule, we treat it as a negative result. Overall, NC and LTB patient-specific analyses across discovery and test sets responded minimally in the set of ligands analyzed. NC patient-specific serum IgG binding assays of 15 resynthesized hit compounds were only positive for binding in ligands 2-B, 7, and 9-A, though only 9-A with modest competition. Only one LTB discovery set patient responded to ligand 13 bound, but more signals are observed in the larger test set. LTB test set patients 29 and 33 respond specifically to multiple ligands. Of the LTB test test, 7/44 samples respond specifically to at least one ligand. 9/10 ATB discovery set patients responded specifically to at least one ligand though binding was not evenly distributed between patients and ligands. For example, 1, 2-B, 2-C, 3, and 4 seem to respond similarly in ATB discovery patients #1 and #3, a trend that ATB test patients #5, #28, and #38 recapitulate. Likewise, ATB discovery patient #10 responds to 8/15 validation hits. Overall 11/40 ATB test patients respond specifically to at least one ligand.

Figure 5. Patient serum IgG binding profiles.

Each hit ligand's serum IgG binding was evaluated for individual patient serum samples classified as TB negative control, latent TB, or active TB. Samples of each classification were either a component of “discovery” serum pools used for library screening or additional “test” samples. The binding behavior of each serum sample is displayed as side-by-side color-coded bars. The left bar indicates whether IgG binding exceeded the statistical significance threshold for the ligand, the right bar indicates the fraction of serum IgG bound in the presence of soluble ligand as the competitor (10 μM).

The competition binding data guided the selection of 4 ligands (1, 2-B, 4, 7) that maximally sampled the ATB discovery set patient samples. 6/10 ATB discovery set serum samples contain IgGs that bind selectively to one of the four structures with > 50% soluble ligand competition. No significant antibody binding to these compounds was observed in the LTB discovery samples, whereas antibodies in two of the TB negative control samples were retained by hits 2-B and 7, respectively. However, in these cases, less than 50% of the signal was competed. All NC and LTB discovery patient samples bind with < 50% soluble ligand completion. The panel exhibits 60% sensitivity, 100% specificity, 100% positive predictive value (PPV), and 83% negative predictive value (NPV) for all discovery set samples. The same panel exhibits 30% sensitivity, 96% specificity, 83% PPV, and 70% NPV for all discovery and test set samples.

Antigen discovery

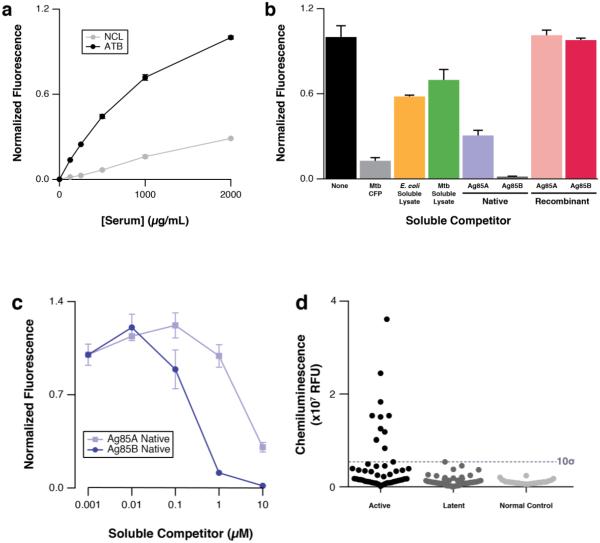

Competition binding analysis of pooled ATB serum samples with 2-B and a variety of Mtb-associated proteins was performed in an attempt to identify the native antigen that 2-B mimics. Ligand 2-B exhibited strong and selective ATB serum IgG binding (Fig. 6a). Culture filtrate proteins (CFP) derived from several virulent Mtb strains (HN878, CDC1551, H37Rv) competed efficiently for binding whereas the E. coli and Mtb lysates competed weakly (Fig. 6b), suggesting that the antigen might be secreted. Further examination of several secreted proteins purified from Mtb revealed that Ag85A and Ag85B compete strongly with 2-B for binding ATB serum IgGs. Competition titration analysis of Ag85A and Ag85B with 2-B showed that Ag85B bound ATB IgGs ~10-fold better than Ag85A (Fig. 6c) and we concluded that compound 2-B mimics an epitope displayed on the native Ag85B. All other purified native and recombinant Mtb proteins, including the recombinant forms of Ag85A and Ag85B, did not compete with 2-B for ATB serum binding (Supplementary Fig. S26). Western analysis of native Ag85B, H37Rv culture filtrate proteins, and CDC1551 culture filtrate proteins using either antibodies that were affinity purified from ATB patient serum on a column functionalized with compound 2-B or anti-Ag85 complex indicated that 2-B-specific antibodies specifically react with Ag85B, again supporting the hypothesis that 2-B is an epitope surrogate of Ag85B (Supplementary Fig. 27). Immobilized native Ag85B used in an ELISA experiment analogous to the patient-specific epitope surrogate experiments yielded a diagnostic sensitivity of 22% and specificity of 100% for the entire collection of discovery and test patient serum samples (Fig. 6d).

Figure 6. Hit compound validation and native antigen identification.

(a) Beads displaying 2-B bound statistically significantly more ATB discovery serum pool IgG compared to the NCL discovery serum pool IgG over a wide range of [serum]. Competition binding analysis of 2-B revealed competitive binding of hypervirulent culture filtrate proteins (CFP, 250 μg/mL) derived from several hypervirulent Mtb strains (HN878, CDC1551, H37Rv), while E. coli and Mtb lysates weakly competed (b). Purified Mtb proteins Ag85A and Ag85B competed (the latter strongly so) though the recombinantly expressed forms were unreactive. (c) Competition titration analysis of native Ag85A and Ag85B with beads displaying 2-B revealed selective reactivity with Ag85B. (d) ELISA analysis of all serum samples using non-specifically immobilized native Ag85B as the antigen yielded 22% diagnostic sensitivity and 100% specificity.

Discussion

Using a DNA-encoded combinatorial library for differentially probing the IgG repertoire of case and control serum samples introduced numerous advantages for epitope surrogate discovery related to the orders of magnitude increases in throughput that FACS and NGS enable. The small (10 μm) TentaGel beads employed for library construction both facilitate large library synthesis (each gram of resin contains 1000-fold more 10-μm beads than conventional 90-μm beads) and the use of FACS-based screening, which quantitatively analyzes and collects several thousand compound beads per second. This represents a vast improvement over manual bead picking, which is slow, manual, and subjective in the absence of custom screening technology29. The greatly enhanced throughput of NGS-based structure elucidation uniquely provided rapid and deep analysis of hit structures, critical for matching the throughput of FACS30. These expansive data not only revealed hit structures, but insight into structural features important for IgG binding. For example, in the screen described here, the data argue that conformational constraint is important for IgG binding, in agreement with previous screens of non-DNA-encoded oligomer libraries27. The library is ~6% peptoid (less conformationally constrained) in Pos2 and Pos3, but this motif appeared in only 0.9% of the hit structures.

DNA-encoded synthesis also permitted the use of structurally diverse BBs that otherwise confound MS-based structure elucidation. Incorporation of heterocycle-containing haloacids26 and chloropentenoic acid27 BBs conformationally constrains the main chain scaffold, potentially mitigating the entropic penalty of binding associated with the “floppier” peptoid chemotype. The MS fragmentation spectra of oligomers composed of these BBs are complex, however, and almost untenable in a library31. The hit structure families of this screen almost ubiquitously featured such BBs, resulting in highly heterogeneous main chain scaffolds. Similarly, imperfect or unanticipated reactivity can generate cryptic signals that compromise MS analysis. DNA-encoded synthesis readily facilitated the elucidation of products arising from such reactivities as well. For example, some compounds with a terminal N-(3-aminopropyl)-2-pyrrolidinone moiety (e.g. 2) unexpectedly rearranged upon release from the beads with some rearrangement products (e.g., 2-B) performing better than the parent compound. The −18 m/z rearrangement product, which for some hits was the major product, would have been nearly impossible to deduce by MS alone, but was readily rationalized upon inspection and reproduction of the DNA-encoded synthesis history. DNA-encoded synthesis may begin to relax decades-old yield and purity constraints of library synthesis reactions as these and other results from DNA-encoded combinatorial libraries are establishing that chemistry can be “error-prone” as long as the encoded synthesis history is reproducible at scale32 and preserves sufficient PCR-viable DNA for decoding33.

The introduction of bead-specific barcodes marked a significant advance in encoding that is uniquely critical to OBOC screening. High false discovery rates are common and problematic for on-bead screening, but observing a hit multiple times on distinct beads (redundancy) signals authentic target binding34,35. In our previous language design, identical compounds present on multiple beads would be indistinguishable by sequencing25. We conceived bead-specific barcodes to count such redundant hits, which occur at frequencies in these experiments requiring few distinct barcodes for accurate counting. The probability of correctly counting redundant hit beads using bead-specific barcodes is identical to the classic birthday problem36: “how many students must be in a class to guarantee that at least two students share a birthday?” Here, the barcodes are the birthdays, the beads are the students, and “birthday twins” are beads that will be miscounted by serendipitously sharing identical bead-specific barcodes. The probability, P, of N beads displaying unique bead-specific barcodes selected from B total barcodes and therefore being correctly counted is:

| (1) |

For this study, P = 88% for N=5 (the typical number of library copies observed in a FACS experiment) and B = 80 bead-specific barcodes. As barcodes are combinatorially generated, it is straightforward to access very large B either by using more sequence modules per position25, reassigning synthesis encoding positions to bead barcoding, or further expanding the number of positions. However, the modest B of this study was sufficient to develop a top-down structure census that, combined with bottom-up consensus analysis, formed the foundation of a highly effective hit prioritization strategy and striking validation success rate (16/21).

The DNA-encoded library screen efficiently identified small molecules that bind specifically to ATB discovery patient serum-derived IgGs and not those present in the NCL discovery set, and binding specificity translated well to the test sets. Of the validated hit structures, all but one (8) bound specifically to at least one ATB discovery set patient's serum IgGs. The LTB and NC discovery set patient sera responses were also gratifyingly clear of positive responses, with only 9-A reporting NC discovery patient #1 as positive and 11 reporting LTB discovery patient #5. It should be pointed out that patients were determined to be NCs based on a negative IGRA test, which is not 100% accurate. Therefore, there remains some possibility that the binding of antibodies from NC patient 1 of the discovery set could be due to an error in that test, though we consider this unlikely. Note that although there was significant binding of antibodies from discovery set NC patients 3 and 4 to compounds 7 and 2-B respectively, very little of this signal could be competed by soluble compound, indicating that this is due to non-specific deposition of antibodies. These are not false positives. No patients in the NC test set responded positively to the validated ligands, however LTB test patients #29 and #33 respond positively and specifically to numerous ligands in a pattern that is strikingly similar to ATB discovery patients #1 and #3, and ATB test set patients #5, #23, #28, and #38. It is possible that ligands 1–4 do not discriminate well between ATB and LTB, though results from the patient-specific binding assays of both NC and LTB discovery sets are at odds with this explanation. Alternatively, in line with newer understanding of the spectrum of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection phases rather than dichotomous classification of active versus latent infection37, these LTB patients could be undergoing progression to active TB and have subclinical disease, and therefore serologically appear as if they are ATB.

One high-priority hit family generated unanticipated side products that selectively bound ATB serum IgGs. Competition binding analysis implicated 2-B, a representative of the family, as an epitope surrogate of the immunodominant Mtb secreted protein Ag85B. The antigen 85 complex (Ag85A, Ag85B, Ag85C) is abundantly secreted during an ATB infection3. The Ag85 proteins are diacylglycerol acyltransferases that mediate the incorporation of mycolic acid into the pathogen's cell wall38 and binding to fibronectin, both of which are critical for infection of and proliferation in macrophages39. That 2-B mimics an epitope of Ag85B is consistent with the antigen's expression in ATB, however, 2-B exhibited no binding competition with Ag85B expressed recombinantly in E. coli. Differences in protein folding between expression hosts or the presence of host-specific PTMs could explain this observation. Further proteomic analysis will clarify this observation, though it is not strictly necessary to elucidate the nature of the antigen mimicry for the purposes of diagnostic development. Some of the other compounds that arose from this screen bind to other antibodies. Future efforts will focus on the elucidation of native antigens for which these compounds are surrogates.

The diagnostic sensitivity of an ELISA using native Ag85B as a non-specifically immobilized antigen was low, consistent with previous work and this study. Ag85B, when used as the sole biomarker for serological diagnosis, yields a spread of sensitivities (4–84%)4. In our hands, the native antigen is also not very sensitive, though quite specific. Notably, however, the immobilized antigen identifies an entirely different population of ATB patients; neither discovery nor test ATB patient sera that were positive for 2-B binding respond positively in the immobilized Ag85B ELISA. We have observed previously that antigen immobilization on an ELISA plate can occlude the epitope that the small-molecule is mimicking14. This does not rule out Ag85B as a diagnostic antigen or viable target for mimicry as a surrogate. On the contrary, Ag85B, when part of a “TB antigen cocktail,” yielded a 98% sensitive diagnostic40, in line with both the previously observed spread of diagnostic sensitivities for all TB antigens studied in isolation and our observations of enhanced sensitivity using the epitope surrogate panel. Further expansion of this panel is underway to generate an analogous small molecule cocktail that is far more economical to produce and thermally stable.

In pursuit of such a panel, the results of this study suggest several points for refinement in future IgG repertoire screens. Both one- and two-color strategies contributed to the hit structures, but the two-color approach was more selective (and experimentally more efficient). One-color screening hits are derived from subtraction of hits that occur in two control screens (the NCL patient serum and secondary detection antibody only) from those observed in the case screen (ATB). The two-color screen obviates the need for separate control screens by detecting NCL-selective ligands and ATB-selective ligands in separate color channels, while non-selective ligands (including ligands of the secondary mFab antibody) populate the diagonal. Furthermore, this approach appears to be more stringent as ~10-fold fewer hits are observed directly as selective ligands in the two-color experiment versus deriving selectivity by comparison of multiple one-color screens. Regardless of screening format, however, several ATB discovery patients' sera dominated the IgG binding profile of the library. For example, the serum of patient #1 binds 1 – 4 while that of patient #10 binds 5 – 8 and 11–13. Coverage of ATB discovery patients #4, #5, #6, and #7 is sparse with only 9-A and 10-A responding, and no hit ligands exists for ATB discovery patient #5. Screening combinatorially pooled case samples in conjunction with a small subset of single-patient case samples (e.g. ATB) could generate an abbreviated survey of each ligand candidate's diagnostic sensitivity and specificity prior to resynthesis, providing even deeper predictive statistics to guide the selection of epitope surrogates for constructing an optimally sensitive panel.

Methods

Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

A NIH Director's New Innovator Award to B.M.P. (Grant OD008535), a grant through the DARPA Fold F(X) Program (N66001-14-2-4057) to T.K. and B.M.P, a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to Opko, and a Graduate Scholarship from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) to M.L.M. supported this work.

Footnotes

Author Contributions G.W., K.R., and K.S. collected study participant specimens and clinical data. K.M. prepared libraries, carried out the screens (with I.S.-K.) and validated hits. P.J.M. conducted all FACS analysis. P.J.M. and A.B.M. conducted library QC analyses and post-screening DNA sequencing. K.M., I.S-K. and T.M.D. identified the native Mtb antigen. J.M.N. re-synthesized all screening huts and elucidated the side product hit structure. B.M.P. and V.C. conceived the structure decoding and prioritization code in R. B.M.P., V.C., and M.L.M. decoded and prioritized the ATB-specific hits. B.M.P. conceived the bead-specific barcoding. T.K. conceived the TB serum binding screen. M.L.M., K.M., B.M.P., and T.K. analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

Competing Financial Interests T.K. is a significant stockholder in Opko Health, Inc.

References

- (1).2015 Global Tuberculosis Report. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Walzl G, Ronacher K, Hanekom W, Scriba TJ, Zumla A. Immunological biomarkers of tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:343–354. doi: 10.1038/nri2960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Kunnath-Velayudhan S, Salamon H, Wang H-Y, Davidow AL, Molina DM, Huynh VT, Cirillo DM, Michel G, Talbot EA, Perkins MD, Felgner PL, Liang X, Gennaro ML. Dynamic antibody responses to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14703–14708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009080107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Steingart KR, Dendukuri N, Henry M, Schiller I, Nahid P, Hopewell PC, Ramsay A, Pai M, Laal S. Performance of purified antigens for serodiagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis: a meta-analysis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:260–276. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00355-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).van Els CACM, Corbière V, Smits K, van Gaans-van den Brink JAM, Poelen MCM, Mascart F, Meiring HD, Locht C. Toward understanding the essence of post-translational modifications for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis immunoproteome. Front Immunol. 2014;5:361. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Davies DH, Liang X, Hernandez JE, Randall A, Hirst S, Mu Y, Romero KM, Nguyen TT, Kalantari-Dehaghi M, Crotty S, Baldi P, Villarreal LP, Felgner PL. Profiling the humoral immune response to infection by using proteome microarrays: high-throughput vaccine and diagnostic antigen discovery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:547–552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408782102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Geysen HM, Rodda SJ, Mason TJ. A priori delineation of a peptide which mimics a discontinuous antigenic determinant. Mol. Immunol. 1986;23:709–715. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(86)90081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Gevorkian G, Segura E, Acero G, Palma JP, Espitia C, Manoutcharian K, López-Marín LM. Peptide mimotopes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis carbohydrate immunodeterminants. Biochem J. 2005;387:411–417. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Liu S, Han W, Sun C, Lei L, Feng X, Yan S, Diao Y, Gao Y, Zhao H, Liu Q, Yao C, Li M. Subtractive screening with the Mycobacterium tuberculosis surface protein phage display library. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2011;91:579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Simon RJ, Kania RS, Zuckermann RN, Huebner VD, Jewell DA, Banville S, Ng S, Wang L, Rosenberg S, Marlowe CK. Peptoids: a modular approach to drug discovery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:9367–9371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Reddy MM, Wilson R, Wilson J, Connell S, Gocke A, Hynan L, German D, Kodadek T. Identification of candidate IgG biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease via combinatorial library screening. Cell. 2011;144:132–142. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Raveendra BL, Wu H, Baccala R, Reddy MM, Schilke J, Bennett JL, Theofilopoulos AN, Kodadek T. Discovery of peptoid ligands for anti-aquaporin 4 antibodies. Chem Biol. 2013;20:351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Sarkar M, Liu Y, Morimoto J, Peng H, Aquino C, Rader C, Chiorazzi N, Kodadek T. Recognition of antigen-specific B-cell receptors from chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients by synthetic antigen surrogates. Chem Biol. 2014;21:1670–1679. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Doran TM, Simanski S, Kodadek T. Discovery of native autoantigens via antigen surrogate technology: application to type 1 diabetes. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:401–412. doi: 10.1021/cb5007618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Doran TM, Morimoto J, Simanski S, Koesema EJ, Clark LF, Pels K, Stoops SL, Pugliese A, Skyler JS, Kodadek T. Discovery of phosphorylated peripherin as a major humoral autoantigen in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cell Chem Biol. 2016;23:618–628. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Miller SM, Simon RJ, Ng S, Zuckermann RN, Kerr JM, Moos WH. Proteolytic studies of homologous peptide and N-substituted glycine peptoid oligomers. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1994;4:2657–2662. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Zuckermann RN, Kerr JM, Kent S, Moos WH. Efficient method for the preparation of peptoids [oligo(N-substituted glycines)] by submonomer solid-phase synthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:10646–10647. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Ryvkin A, Ashkenazy H, Smelyanski L, Kaplan G, Penn O, Weiss-Ottolenghi Y, Privman E, Ngam PB, Woodward JE, May GD, Bell C, Pupko T, Gershoni JM. Deep panning: steps towards probing the IgOme. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41469. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Brenner S, Lerner RA. Encoded combinatorial chemistry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5381–5383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Clark MA, Acharya RA, Arico-Muendel CC, Belyanskaya SL, Benjamin DR, Carlson NR, Centrella PA, Chiu CH, Creaser SP, Cuozzo JW, Davie CP, Ding Y, Franklin GJ, Franzen KD, Gefter ML, Hale SP, Hansen NJV, Israel DI, Jiang J, Kavarana MJ, Kelley MS, Kollmann CS, Li F, Lind K, Mataruse S, Medeiros PF, Messer JA, Myers P, O'Keefe H, Oliff MC, Rise CE, Satz AL, Skinner SR, Svendsen JL, Tang L, van Vloten K, Wagner RW, Yao G, Zhao B, Morgan BA. Design, synthesis and selection of DNA-encoded small-molecule libraries. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:647–654. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Mannocci L, Zhang Y, Scheuermann J, Leimbacher M, De Bellis G, Rizzi E, Dumelin C, Melkko S, Neri D. High-throughput sequencing allows the identification of binding molecules isolated from DNA-encoded chemical libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17670–17675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805130105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Disch JS, Evindar G, Chiu CH, Blum CA, Dai H, Jin L, Schuman E, Lind KE, Belyanskaya SL, Deng J, Coppo F, Aquilani L, Graybill TL, Cuozzo JW, Lavu S, Mao C, Vlasuk GP, Perni RB. Discovery of thieno[3,2-d]pyrimidine-6-carboxamides as potent inhibitors of SIRT1, SIRT2, and SIRT3. J Med Chem. 2013;56:3666–3679. doi: 10.1021/jm400204k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Encinas L, O'Keefe H, Neu M, Remuiñán MJ, Patel AM, Guardia A, Davie CP, Pérez-Macías N, Yang H, Convery MA, Messer JA, Pérez-Herrán E, Centrella PA, Álvarez-Gómez D, Clark MA, Huss S, O'Donovan GK, Ortega-Muro F, McDowell W, Castañeda P, Arico-Muendel CC, Pajk S, Rullás J, Angulo-Barturen I, Álvarez-Ruíz E, Mendoza-Losana A, Ballell Pages L, Castro-Pichel J, Evindar G. Encoded library technology as a source of hits for the discovery and lead optimization of a potent and selective class of bactericidal direct inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis InhA. J Med Chem. 2014;57:1276–1288. doi: 10.1021/jm401326j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Yang H, Medeiros PF, Raha K, Elkins P, Lind KE, Lehr R, Adams ND, Burgess JL, Schmidt SJ, Knight SD, Auger KR, Schaber MD, Franklin GJ, Ding Y, DeLorey JL, Centrella PA, Mataruse S, Skinner SR, Clark MA, Cuozzo JW, Evindar G. Discovery of a potent class of PI3Kα inhibitors with unique binding mode via encoded library technology (ELT) ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:531–536. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).MacConnell AB, McEnaney PJ, Cavett VJ, Paegel BM. DNA-encoded solid-phase synthesis: encoding language design and complex oligomer library synthesis. ACS Comb Sci. 2015;17:518–534. doi: 10.1021/acscombsci.5b00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Aditya A, Kodadek T. Incorporation of heterocycles into the backbone of peptoids to generate diverse peptoid-inspired one bead one compound libraries. ACS Comb Sci. 2012;14:164–169. doi: 10.1021/co200195t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Aquino C, Sarkar M, Chalmers MJ, Mendes K, Kodadek T, Micalizio GC. A biomimetic polyketide-inspired approach to small-molecule ligand discovery. Nat Chem. 2012;4:99–104. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Doran TM, Kodadek T. A liquid array platform for the multiplexed analysis of synthetic molecule protein-interactions. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:339–346. doi: 10.1021/cb400806r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Hintersteiner M, Buehler C, Uhl V, Schmied M, Müller J, Kottig K, Auer M. Confocal nanoscanning, bead picking (CONA): PickoScreen microscopes for automated and quantitative screening of one-bead one-compound libraries. J Comb Chem. 2009;11:886–894. doi: 10.1021/cc900059q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Needels MC, Jones DG, Tate EH, Heinkel GL, Kochersperger LM, Dower WJ, Barrett RW, Gallop MA. Generation and screening of an oligonucleotide-encoded synthetic peptide library. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10700–10704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Sarkar M, Pascal BD, Steckler C, Aquino C, Micalizio GC, Kodadek T, Chalmers MJ. Decoding split and pool combinatorial libraries with electron-transfer dissociation tandem mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2013;24:1026–1036. doi: 10.1007/s13361-013-0633-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Satz AL. Simulated screens of DNA encoded libraries: the potential influence of chemical synthesis fidelity on interpretation of structure-activity relationships. ACS Comb Sci. 2016;18:415–424. doi: 10.1021/acscombsci.6b00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Malone ML, Paegel BM. What is a “DNA-compatible” reaction? ACS Comb Sci. 2016;18:182–187. doi: 10.1021/acscombsci.5b00198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Appell KC, Chung TDY, Ohlmeyer MJH, Sigal NH, Baldwin JJ, Chelsky D. Biological screening of a large combinatorial library. J Biomol Screen. 1996;1:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Doran TM, Gao Y, Mendes K, Dean S, Simanski S, Kodadek T. Utility of redundant combinatorial libraries in distinguishing high and low quality screening hits. ACS Comb Sci. 2014;16:259–270. doi: 10.1021/co500030f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).DasGupta A. The matching, birthday and the strong birthday problem: a contemporary review. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference. 2005;130:377–389. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Barry CE, Boshoff HI, Dartois V, Dick T, Ehrt S, Flynn J, Schnappinger D, Wilkinson RJ, Young D. The spectrum of latent tuberculosis: rethinking the biology and intervention strategies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:845–855. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Belisle JT, Vissa VD, Sievert T, Takayama K, Brennan PJ, Besra GS. Role of the major antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in cell wall biogenesis. Science. 1997;276:1420–1422. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Wiker HG, Harboe M. The antigen 85 complex: a major secretion product of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:648–661. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.4.648-661.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Tiwari D, Tiwari RP, Chandra R, Bisen PS, Haque S. Efficient ELISA for diagnosis of active tuberculosis employing a cocktail of secretory proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Folia Biol. (Praha) 2014;60:10–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.