Abstract

A variant ecotropic Friend murine leukemia virus, F-S MLV, is capable of inducing the formation of large multinucleated syncytia in Mus dunni cells. This cytopathicity resembles that of Spl574 MLV, a novel variant recently isolated from the spleen of a Mus spicilegus mouse neonatally inoculated with Moloney MLV. F-S MLV is an N-tropic Friend MLV that also has the unusual ability to infect hamster cells, which are normally resistant to mouse ecotropic MLVs. Syncytium induction by both F-S MLV and Spl574 is accompanied by the accumulation of large amounts of unintegrated viral DNA, a hallmark of pathogenic retroviruses, but not previously reported for mouse ecotropic gammaretroviruses. Sequencing and site-specific mutagenesis determined that the syncytium-inducing phenotype of F-S MLV can be attributed to a single amino acid substitution (S84A) in the VRA region of the viral env gene. This site corresponds to that of the single substitution previously shown to be responsible for the cytopathicity of Spl574, S82F. The S84A substitution in F-S MLV also contributes to the ability of this virus to infect hamster cells, but Spl574 MLV is unable to infect hamster cells. Because this serine residue is one of the critical amino acids that form the CAT-1 receptor binding site, and because M. dunni and hamster cells have variant CAT-1 receptors, these results suggest that syncytium formation as well as altered host range may be a consequence of altered interaction between virus and receptor.

Specific receptors mediate the entry of retroviruses into susceptible cells. Mutations in the critical residues that govern this virus-receptor interaction can potentially alter host range and contribute to cytopathicity; such phenotypic variants are common among the pathogenic lentiviruses and retroviruses. Thus, the pathogenic avian leukosis viruses of host range subgroups B, D, and F can induce cytopathic effects in cultured chicken cells (27). Also, the lentiviruses that induce immunodeficiency, as well as some pathogenic bovine and feline leukemia viruses, can produce large multinucleated syncytia in cultures of susceptible cells (2, 22).

Among the ecotropic mouse gammaretroviruses, cytopathic variants are rare. These rare isolates include variants of the Friend and Moloney mouse leukemia viruses (MLVs) that are capable of inducing syncytium formation. The first of these cytopathic viruses, TR1.3, is a neuropathic Friend MLV (FrMLV) variant that is tropic for brain endothelial cells (BCEC) and induces degenerative changes in these cells, leading to central nervous system disease. This virus also induces the formation of large, multinucleated syncytia in the SC-1 cell line (20). A second cytopathic MLV is Spl574, a Moloney MLV (MoMLV) variant of unknown pathogenicity that was recently isolated from the wild mouse species Mus spicilegus (12). Spl574 induces syncytia in Mus dunni cells and has reduced infectivity for other mouse cell lines. The syncytium-inducing and host range properties of these two mouse viruses have been attributed to different specific amino acid substitutions in the VRA region of SU env: W102G for TR1.3 and S82F for Spl574 (12, 20).

Differences in pathogenic properties and tropism have been noted among the various stocks of FrMLV. The ecotropic FrMLV biologically cloned from the original Friend stock induces erythroleukemia associated with severe anemia in susceptible mice. The PVC-211 variant, isolated after passage in rats (13), causes a rapidly progressive neurological disease in both rats and mice but does not cause erythroleukemia. PVC-211 can, like TR1.3, infect rat BCECs that are resistant to other ecotropic MLVs, including the prototypical FrMLV. The BCEC tropism of PVC-211 has been attributed to two amino acid substitutions in the VRA region of SU env, E116G and E129K (16), and these substitutions also contribute to the unusual ability of this isolate to infect hamster cells (17).

In the course of studying MLV host range variants, we observed unexpected differences among FrMLV isolates in host range and in cytopathicity. Earlier studies had noted that some Friend virus isolates could cause syncytium formation in M. dunni cells (15), but these studies did not systematically screen Friend isolates for this phenotype nor attempt to define its genetic basis. In the present study, we identified one FrMLV isolate capable of inducing syncytia and also able to infect hamster cells. We determined that a single amino acid substitution in VRA is responsible for cytopathicity and contributes to its expanded host range. We have also determined that syncytium formation with this FrMLV isolate or with the MoMLV variant Spl574 is accompanied by the accumulation of large amounts of unintegrated viral DNA, a hallmark of pathogenic retroviruses (26).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cells.

Three FrMLV isolates, F-S MLV, FrMLV N-B, and FBLV, were obtained from J. W. Hartley (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.). F-S MLV is an N-tropic FrMLV isolate. FrMLV F-B (NB-tropic complex) was originally provided by F. Lilly (Albert Einstein College of Medicine) and was maintained by passage in BALB/c or NFS/N mice. FBLV (NB-tropic FrMLV) is a biologically cloned virus originally generated by R. Risser (University of Wisconsin—Madison). A fourth variant, FrMLV clone 57 (FrMLV57), was obtained as a molecular clone from S. Ruscetti (National Cancer Institute—Frederick Cancer Research Facility, Frederick, Md.) (19). FrMLV57 virus stocks were prepared after transfection of this clone into NIH 3T3 cells. AKV MLV and ecotropic MoMLV were also obtained from J. Hartley. Spl574 was isolated from an M. spicilegus mouse neonatally inoculated with MoMLV (12).

Virus stocks were made by collecting culture fluids from infected or transfected cells. These stocks were used to infect cultures of NIH 3T3, SC-1 (9), M. dunni (15), Chinese hamster E36 (8), Chinese hamster CHO-K1 (ATCC CCL-61), and Syrian hamster BHK (ATCC CCL-10) cells and primary cultures of embryo fibroblasts prepared from embryos of NFS/N and DBA/2J mice. Cultures were tested for susceptibility to virus infection by the XC test (23). Cells were plated at 1 × 105 to 2 × 105 cells/60-mm dish and infected with 0.2 ml of appropriate dilutions of virus stocks in the presence of Polybrene (4 μg/ml; Aldrich, Milwaukee, Wis.). Cells were irradiated 4 days after virus infection and overlaid with 106 XC cells/plate. Plates were fixed and stained 3 days later and examined for plaques of syncytia.

To measure syncytium formation in M. dunni cells, 2 × 104 M. dunni cells in six-well tissue culture plates or 105 cells in 60-mm plates were infected with virus-containing medium in the presence of Polybrene. After 2 to 4 days, the cells were examined by light microscopy either directly or after being fixed in methanol and stained with 0.5% methylene blue. Cells were examined using objective lenses of 4 to 20× and photographed using a Nikon TS100 microscope and DXM1200 digital camera. Viable cells in infected cultures were counted after trypsinization and trypan blue exclusion.

DNA extraction and Southern blotting.

High-molecular-weight DNA was isolated from virus-infected cultures by standard protocols. Unintegrated viral DNA was extracted using the Hirt fractionation method (10). Briefly, the Hirt supernatant and pellet fractions were separated by centrifugation, and the supernatant was treated with 200 μg of proteinase K/ml and extracted twice with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1). The aqueous phase was adjusted to 0.3 M NaOAc, and DNA was precipitated with an equal volume of 2-propanol. The DNA was dissolved in 10 mM Tris-HCl-1 mM EDTA (pH 7.4).

DNAs were digested with restriction enzymes, electrophoresed on 0.4% agarose gels, transferred to nylon membranes (Hybond N+; Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.), and hybridized with radiolabeled probe. As probe, a 216-bp segment of the MoMLV env (MOenv; GenBank accession no. J02255) was amplified from the DNA of virus-infected cells by PCR with primers 5′-GGACAAGATCCAGGGCTTACA-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-TACTAAGTTTAGCAGCCTATT-3′ (reverse primer). A BamHI 306-bp segment of the MoMLV pol was also used as a nonspecific MLV probe. Gels were analyzed using a Fuji FLA-2000 PhosphorImager. Bands were quantitated using FujiX Image Gauge software.

Cloning, sequencing, and mutagenesis.

cDNA was prepared from NIH 3T3 cells infected with different MLVs and used as the reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) substrate. The following primers based on the GenBank MLV sequence J01998 were used to amplify a 340-bp segment of the viral env containing VRA (Fig. 1): Frenv-1, 5′-ATCACCCTCTGTGGACTTGG-3′ (FrMLV env forward primer); Frenv-2, 5′-CCCCAAGAGGCACAATAGAA-3′ (FrMLV env reverse primer).

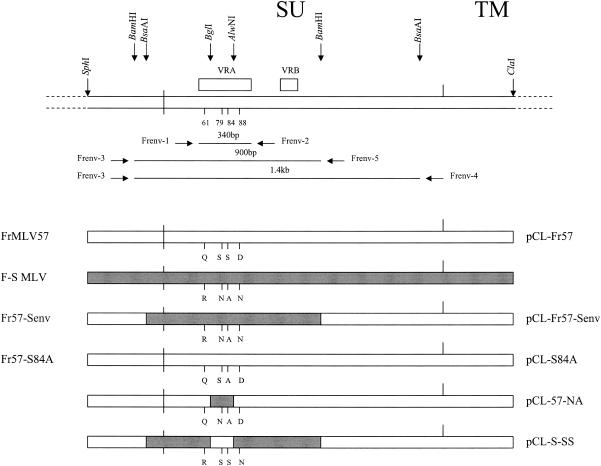

FIG. 1.

At the top is shown the general structure of SU env with flanking segments of pol and TM. The vertical arrows locate the indicated restriction enzyme sites, and boxes are used to position VRA and VRB. Vertical lines indicate four specific amino acid residues within VRA. Horizontal arrows identify the PCR primers and their products. The lower half of the figure shows the structures of mutant and chimeric env genes, with the four infectious virus clones listed to the left and the five env genes used for pseudotype production on the right.

The PCRs were carried out in a GeneAmp PCR system 9700 machine (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The reactions were performed for 35 cycles with a 30-s DNA denaturation step at 95°C, a 30-s annealing step, and a 1-min extension step at 72°C. The annealing temperature in the first cycle, 63°C, was subsequently reduced by 1°C each cycle for the next 8 cycles and was then maintained at 55°C for the remaining 27 cycles. The PCR products were cloned into the pCR2.1-TOPO vector (Invitrogen Co., Carlsbad, Calif.) and sequenced.

A chimeric virus was generated in which the 5′ env region of FrMLV57 was replaced with the corresponding region of F-S MLV. The following primers based on GenBank accession no. X02794 were used to amplify segments of the viral env genes (Fig. 1): Frenv-3, 5′-CCCACCGCTCTCAAAGTAGA-3′ (FrMLV env forward primer); Frenv-4, 5′-ACTGGGAGGATGGTAGGTGA-3′ (FrMLV env reverse primer); Frenv-5, 5′-GGACCCGAGGTCCTAGATTT-3′ (FrMLV env reverse primer).

The Frenv-3 and Frenv-4 primers were used to amplify a 1.4-kb env fragment from FrMLV57 containing two BsaAI cleavage sites. Frenv-3 and Frenv-5 were designed to amplify a 900-bp env fragment from F-S MLV containing two BamHI cleavage sites. These two PCR products were cloned into the pCR2.1-TOPO vector and sequenced. To create an FrMLV57 clone containing the 5′ region of F-S MLV, a series of exchanges were made. First, the 830-bp BamHI fragment in the 1.4-kb env subclone of FrMLV57 was replaced with the corresponding fragment from the F-S MLV env subclone. Next, the 1.3-kb BsaAI fragment was removed from this modified env and ligated into the full-length FrMLV57 clone from which the corresponding fragment had been excised. This clone, Fr57-Senv, contained an 820-bp BsaAI-BamHI substitution, which was confirmed by sequencing.

The amino acid substitution S84A was introduced into FrMLV57 by using the Stratagene (La Jolla, Calif.) ExSite PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis kit as follows. BsaAI digestion of the FrMLV57 plasmid DNA produced a 1.3-kb env fragment containing VRA that corresponded to nucleotides 5733 to 7057 of the viral genome. This 1.3-kb fragment was subcloned into the vector pCR2.1-TOPO. The amino acid substitution S84A was introduced using the following oligonucleotides based on GenBank MLV sequence X02794: forward primer, 5′-CAGTGCAGGCTGTGCCAGAGACTG-3′; reverse primer, 5′-CAGTCTCTGGCACAGCCTGCACTG-3′. The mutated fragment was then removed as a 1.3-kb BsaAI fragment and was ligated to FrMLV57 plasmid DNA from which the corresponding 1.3-kb fragment had been deleted. This mutated virus was designated Fr57-S84A.

Transfection and infection.

Viral DNA clones were first digested with EcoRI to release the inserts and treated with T4 ligase overnight. The DNAs were introduced into NIH 3T3 cells using the QIAGEN (Valencia, Calif.) PolyFect transfection kit. After 3 days in culture, supernatants were harvested and assayed for RT as described previously (28).

Pseudotype assay.

LacZ pseudotype virus was generated by cotransfection of human 293 cells with expression vectors containing various env genes and pCLMFG-LacZ (Imgenex Co., San Diego, Calif.). The SU genes of FrMLV57, the Fr57-Senv chimera, and the Fr57-S84A mutant were cloned into the pCL-Eco retrovirus packaging vector (Imgenex Co.) by ligating the 2.5-kb SphI-ClaI SU-containing fragments of these clones into the SphI-ClaI cloning site (Fig. 1). To construct pCL-57-NA (containing the F-S MLV-derived substitutions S79N and S84A), the 53-bp BglI-AlwNI fragment within the env gene of pCL-Fr57 was excised and replaced with the corresponding fragment of clone pCL-Fr57-Senv. To construct pCL-S-SS (containing the F-S MLV substitutions Q61R and D88N), the BglI-AlwNI fragment of pCL-Fr57-Senv was replaced with the corresponding fragment of FrMLV57. Pseudotype virus-containing supernatants were collected from transfected 293 cells, filtered, and used to infect NIH 3T3 and Chinese hamster E36 cells that had been plated in six-well culture dishes at a density of 1.5 × 105 per well. The cells were infected with 1 ml of pseudotype virus in the presence of 8 μg of Polybrene/ml for 3 h before 2 ml of fresh medium was added to each well. One day after infection, cells were fixed with 0.4% glutaraldehyde and assayed for β-galactosidase activity using as substrate 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (2 mg/ml; ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, Ohio). Infectious titers were expressed as the number of blue CFU per 200 μl of virus supernatant.

Cloning and sequencing of the E36 Chinese hamster CAT-1 receptor gene.

A segment of the Chinese hamster CAT-1 receptor gene containing the third extracellular loop was amplified from E36 cell DNA by PCR with forward (5′-GCCCAAAACCCTGACATATTAGCTGTG) and reverse (5′-GCCTTCTGGGGGTTCTTGACTTCTTCA) primers derived from the CHO cell Chinese hamster CAT-1 sequence (GenBank accession no. U49797). The 370-bp PCR product was cloned into the pCR2.1-TOPO vector and sequenced.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

Sequences for the F-S MLV and FBLV SU genes have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AY563028 and AY563029.

RESULTS

Cytopathic variants of MoMLV and FrMLV.

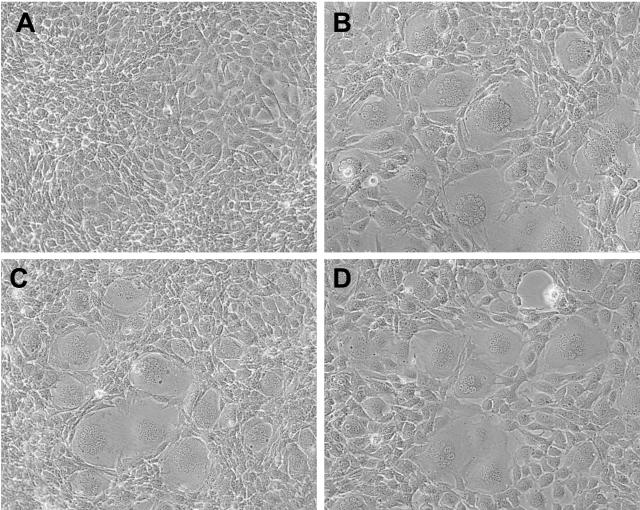

Mouse cells were infected with four different isolates of ecotropic FrMLV. One of these viruses, F-S MLV, induced the formation of large syncytia of multinucleated cells in M. dunni cultures (Fig. 2B). Syncytia appear 2 days after infection and commonly contain 5 to 10 nuclei but can be larger if cultures are at low density when infected. F-S MLV infection does not induce syncytia in other mouse cell lines, including SC-1, NIH 3T3, or primary fibroblasts derived from various mouse strains. None of the three other FrMLV isolates (FBLV, FrMLV57, or FrMLV N-B) produced syncytia or other cytopathic changes in any of the mouse cells (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

(A) Uninfected M. dunni cells. (B) M. dunni cells 3 days after infection with F-S MLV. Syncytia are apparent in virtually all fields examined in cultures infected at an MOI of >0.1. (C) M. dunni cells 3 days after infection with the chimeric virus Fr57-Senv, which contains the 5′ half of the F-S MLV env gene. (D) M. dunni cells 3 days after infection with Fr57-S84A. Objective lens magnification was ×20.

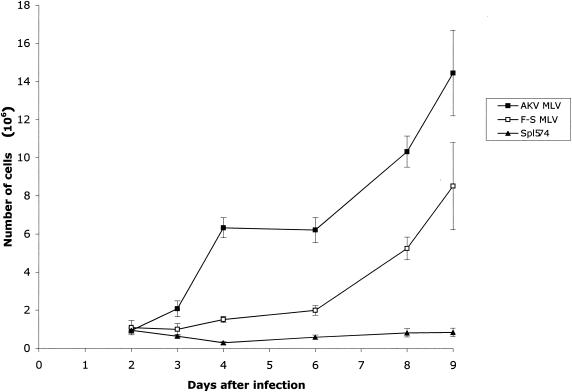

This syncytium-inducing phenotype of F-S MLV resembles that of the previously described cytopathic virus Spl574, an MoMLV variant that also induces syncytia only in M. dunni cells (12). Cultures infected with either of these viruses are characterized by progressive deterioration and the accumulation of cell debris in the culture medium consistent with cell killing. We quantitated this cytopathic effect in infected cultures over a period of 9 days by scoring the number of cells that failed to exclude the vital dye trypan blue (Fig. 3). Multiple independent cultures were infected at multiplicities of infection (MOIs) of 0.5 to 3 with three different viruses: F-S MLV, Spl574, or the noncytopathic virus AKV MLV. The number of viable cells in AKV MLV-infected cultures increased over the 9-day period, and the resulting curve was comparable to that for uninfected cultures (data not shown). In contrast, the number of viable cells in cultures infected with Spl574 or F-S MLV was clearly reduced by 3 days postinfection, and this reduction was amplified by the ninth day. The number of viable cells in Spl574-infected cultures did not change for the duration of the experiment, whereas cultures infected with F-S MLV began to show an increase in cell number by 7 days postinfection. Despite this recovery, however, F-S MLV cultures were still seriously depleted of viable cells at 9 days. This type of cytopathicity is a common feature of pathogenic retroviruses but has very rarely been described for ecotropic MLVs.

FIG. 3.

Effect of ecotropic MLV infection on the growth of M. dunni cells. Cells in 60-mm plates were trypsinized at different days after infection with the indicated virus, and viable cells were counted by trypan blue dye exclusion. Values represent the means and standard deviations calculated from counting four samples from each time point.

Altered host range of F-S MLV.

Spl574 differs from its MoMLV progenitor in host range as well as cytopathicity (12), and so we examined F-S MLV for its ability to infect various mouse cell lines. Specifically, Spl574 efficiently infects M. dunni cells but is poorly infectious for other mouse cells, whereas MoMLV efficiently infects all mouse cells except M. dunni. Titers for all four FrMLV isolates were determined on M. dunni, SC-1, and/or NIH 3T3 cells (Table 1). Three of the four isolates showed somewhat reduced titers on M. dunni relative to either SC-1 or NIH 3T3 cells; only F-S MLV replicated equally efficiently on all mouse cells. However, this difference, while reproducible, was minor compared to the restricted replication of Spl574 on mouse cells other than M. dunni.

TABLE 1.

Virus titers of MLV variants in different mouse cell lines

| Virus | Log10 virus titera in:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. dunni | SC-1 | NIH 3T3 | E36 | BHK | CHO-K1 | |

| AKV MLV | 4.4 | 4.1 | 4.1 | — | — | — |

| Friend MLVs | ||||||

| FrMLV-NB | 4.0 | 4.6 | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| FBLV | 3.9 | 5.0 | 5.7 | — | — | NT |

| FrMLV57 | 3.2 | NT | 4.1 | — | NT | NT |

| F-S MLV | 5.95b | 5.1 | 5.8 | 3.0 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| Spl574 | 4.5b | 2.1 | 2.9 | — | — | NT |

| MoMLV | 1.5 | 5.2 | 5.2 | — | — | — |

| Fr57-Senv (chimera) | 3.8b | NT | 4.0 | 1.6 | NT | NT |

| Fr57-S84A (mutant) | 4.7b | 3.8 | 4.3 | — | NT | NT |

Measured as the number of XC PFU in 0.2 ml. —, no plaques were detected in cultures infected with 0.2 ml of undiluted virus stock. NT, not tested.

Syncytia were noted in these cultures.

We also tested these ecotropic MLVs for infectivity on other rodent cells and found that F-S MLV efficiently infected E36 hamster cells, an unexpected result since these cells are not normally infectible by ecotropic MLVs (Table 1). The efficiency of E36 cell infection was dependent on cell density and was substantially reduced in cultures infected at >30% confluency (data not shown), a phenomenon previously reported for gammaretrovirus infection of hamster cells (18). F-S MLV replicated more efficiently on E36 Chinese hamster cells than on BHK cells or CHO-K1 cells. Compared to titers on mouse cells, the F-S MLV titer was generally reduced by 2 to 3 logs on E36 cells and by 3 to 4 logs on BHK and CHO-K1 cells. In comparison, the titers of all other MLVs, including the MoMLV variant Spl574, on these hamster cell lines were below the level of detection. These results indicate that F-S MLV differs from the other FrMLVs in its host range, in addition to its ability to induce syncytia and cell death in cultures of M. dunni cells.

Cloning, sequencing, and mutagenesis.

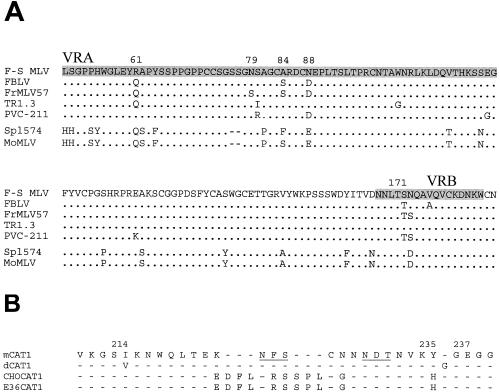

To identify the viral sequences responsible for the altered host range and cytopathic properties of F-S MLV, we cloned and sequenced the 5′ SU env region of F-S MLV and FBLV. Initially, a 340-bp PCR product containing VRA was cloned and sequenced, but subsequently a larger fragment of 0.9 kb was sequenced. These sequences were compared with each other and with previously sequenced FrMLVs, and also with the sequence of the syncytium-inducing virus Spl574 (Fig. 4A). F-S MLV differed from the non-syncytium-inducing viruses FrMLV57 and FBLV by four amino acid substitutions: Q61R, S84A, D88N, and T171S. Three of these substitutions, Q61R, S84A, and D88N, were in the VRA region, and the position of one of these substitutions, S84A, was analogous to that of the S82F substitution responsible for the altered host range and cytopathicity of Spl574 (12).

FIG. 4.

(A) Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequences of a segment of the env gene of F-S MLV with four FrMLV isolates, MoMLV, and Spl574. The VRA and VRB regions are shaded, and the four variant residues that distinguish F-S MLV from the non-syncytium-inducing FrMLVs, FBLV and FrMLV57, are numbered. Sequences for PVC-211, TR1.3, FrMLV57, MoMLV, and Spl574 were previously determined (12, 14, 20, 21, 24). (B) Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequences of the third extracellular loop of the CAT-1 receptor. Sequences for mCAT1, dCAT-1 (M. dunni), and CHO CAT-1 were previously determined (GenBank accession no. M26687, reference 6, and GenBank accession no. U49797, respectively).

A chimeric virus was constructed in which an 820-bp segment of the 5′ env region of F-S MLV replaced the corresponding region in the FrMLV57 clone. This chimera, Fr57-Senv, contained all four of the unique F-S MLV substitutions. Fr57-Senv resembled F-S MLV in its replication in E36 cells and ability to cause syncytia in M. dunni cells (Table 1; Fig. 2C).

Mutagenesis was done to assess the contribution of S84A to the altered properties of this virus. S84A was introduced into the FrMLV57 clone and this mutated virus was found to induce syncytia on M. dunni cells (Fig. 2D), but infection of hamster cells could not be detected with the XC test (Table 1).

We also determined virus host range by using retrovirus vectors expressing five different viral env glycoproteins (Fig. 1) in a single-cycle infection assay that does not rely on syncytia induction, as does the XC test. As shown in Table 2, all five pseudotypes efficiently infected NIH 3T3 cells. The pseudotype with the 5′ half of F-S MLV SU, pCL-Fr57-Senv, infected E36 cells, but the titer was reduced by 2.4 logs relative to that in NIH 3T3; this reduction in infectivity on hamster cells was comparable to that seen for infectious F-S MLV and for infectious virus with this same chimeric env, Fr57-Senv (Table 1). A similar reduction of titer on E36 cells was seen for the pseudotype pCL-57-NA containing a smaller substitution with only S79N and S84A. These results suggest that sequence substitutions within VRA mediate infection of E36 cells. In contrast, infection of E36 cells with the pseudotype pCL-84A was detectable, but only at borderline levels in three of five assays. This low pseudotype titer was consistent with the failure to detect infection with Fr57-S84A virus (Table 1). The Env with S84A alone is thus less infectious than the chimera carrying both S84A and S79N. Since S79N without S84A (in FBLV) does not mediate infection of hamster cells, this result also suggests that S84A contributes to infectivity of hamster cells but that this infectivity is improved in the presence of S79N.

TABLE 2.

Titers of FrMLV LacZ pseudotypes in mouse and hamster cells

| Pseudotype | Log10 titer of LacZ pseudotypesa in:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| NIH 3T3 | E36 | |

| pCL-Fr57 | 4.3 | — |

| pCL-Fr57-Senv | 4.5 | 2.1 |

| pCL-S84A | 4.1 | 0.6b |

| pCL-57-NA | 3.7 | 1.7 |

| pCL-S-SS | 4.1 | — |

Titers are given as CFU per 0.2 ml. —, no plaques were detected in cultures infected with 0.2 ml of undiluted virus stock.

Infectivity was detected in three of five assays.

Sequence analysis of E36 Chinese hamster CAT-1.

One possible explanation for the ability of F-S MLV to infect hamster cells is that these cells encode a CAT-1 receptor that differs from that of mouse cells. While the Chinese hamster CAT-1 gene from CHO cells has been sequenced (5), E36 cells are a lung fibroblast line established from a different random-bred hamster colony (8). Therefore, we cloned and sequenced the third extracellular loop of the CAT-1 receptor from these cells. This sequence was found to be identical to that of CHO cells (5) (Fig. 4B).

Accumulation of unintegrated DNA in virus-infected cells.

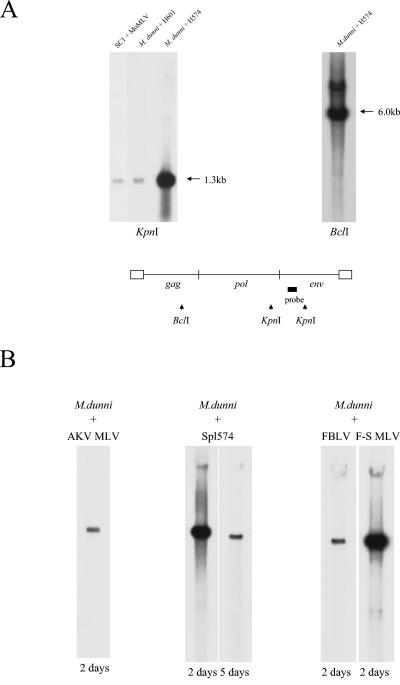

Spl574 was originally isolated from an M. spicilegus mouse (mouse H574) that had been neonatally infected with MoMLV (12). In preliminary experiments done to characterize virus isolates from 13 similarly inoculated M. spicilegus mice, DNA was extracted from M. dunni cells that had been infected with spleen and/or thymus cells of individual MoMLV-infected mice. Figure 5A shows a Southern blot of DNAs extracted from two of these cultures. The H601 lane is representative of 12 of the 13 mice tested, whereas DNA from cultures infected with H574 cells showed unexpectedly high levels of viral DNA. Based on hybridization intensity, the number of copies identified by the MOenv probe was approximately 80 times the number in the DNAs from cultures infected with cells from H601 or from SC-1 cells chronically infected with MoMLV. This is reminiscent of the previous observation that syncytium induction by retroviruses of bovine, cat, human, and avian origins is associated with the accumulation of unintegrated viral DNA (26). To determine if the multiple copies in Spl574-infected cells represented integrated or unintegrated DNA, these same DNA samples were analyzed by Southern blotting following digestion with EcoRI, an enzyme that does not cleave MoMLV, and with BclI, which is expected to cleave the viral genome once. The EcoRI digest produced a smear of high-molecular-weight env fragments with an intense band of 8.2 kb, suggesting that most of the DNA was unintegrated (data not shown). The BclI digest produced an env-containing fragment of 6.0 kb as expected for linear viral DNA (Fig. 5A). These digests also contained less-intense bands forming a doublet at 8.2 to 8.4 kb, representing linearized one and two long terminal repeat circles.

FIG. 5.

Presence of high levels of unintegrated viral DNA in M. dunni cells infected with Spl574 or F-S MLV. (A) High-molecular-weight DNA was isolated from SC-1 cells chronically infected with MoMLV or from M. dunni cells that had been infected with thymus and spleen cells from two different 2-month-old M. spicilegus mice (H574 and H601) that had been neonatally inoculated with MoMLV (12). The infected M. dunni cells were passed twice before DNA extraction. DNAs were digested with KpnI (left) or BclI (right), transferred to nylon membranes, and hybridized with a radiolabeled MOenv probe. The segment of the viral genome that corresponds to this probe is indicated at the bottom of the panel by a shaded box. The three KpnI lanes were cut from the same exposure of a Southern blot. (B) Southern blot analysis of DNAs extracted by the Hirt method from virus-infected cells. Spl574 is the MoMLV variant biologically cloned from M. dunni cells infected with thymus and spleen from mouse H574 (12). DNAs were cleaved with EcoRI, an enzyme that does not cleave any of these viral genomes, and hybridized with a 306-bp BamHI segment of the MoMLV pol gene. The number under each lane represents the number of days postinfection for DNA extraction. The five samples were run on the same gel, and all five lanes were cut from a photograph of the same exposure.

Following this preliminary observation, the Spl574 virus was biologically and molecularly cloned from the M. dunni cultures (12). M. dunni cells were then infected with F-S MLV, Spl574, or AKV MLV at an MOI of 1 to 3, and DNA was extracted by the Hirt method (10) 2, 5, or 7 days postinfection. Uncut DNA was run on Southern blot assays and hybridized with a 306-bp MLV pol probe. Hirt DNA from M. dunni cells infected with Spl574 and F-S MLV produced intense bands at 8.2 kb, a signal 13-fold more intense than the comparable band in M. dunni cells infected with AKV MLV or FBLV (Fig. 5B). The amount of viral Hirt DNA decreased with time after infection; DNA extracted 5 days (Fig. 5B) or 7 days after infection was substantially reduced.

DISCUSSION

F-S MLV is a novel Friend ecotropic MLV variant that, like the MoMLV variant Spl574, is capable of inducing syncytia on M. dunni cells. Both viruses also have altered host range, and both viruses have substitutions in the same amino acid that contributes to the formation of the receptor binding site. Specifically, for F-S MLV, the S84A substitution is responsible for cell death and syncytium formation. The S82F substitution in Spl574 is also associated with cell death and syncytium formation as well as reduced efficiency of infection in mouse cells other than M. dunni.

Retroviruses are usually not cytotoxic, but numerous exceptional variants have been identified, including human immunodeficiency virus, avian leukosis virus and, among the gammaretroviruses, some feline leukemia viruses and the polytropic mink cell focus-forming viruses. Now included among these cytopathic viruses are several mouse gammaretroviruses of ecotropic host range. For F-S MLV and Spl574, as with the other cytotoxic retroviruses, infection is associated with the accumulation of large amounts of unintegrated DNA. This accumulation of extrachromosomal DNA is a hallmark of virulence and has been attributed to the absence of superinfection interference (26). Although the mechanism of cell death is unknown, Yoshimura and her colleagues (30) have proposed that the large amount of unintegrated DNA generated by superinfection may induce apoptosis.

While the role of extrachromosomal DNA in cell killing is still under investigation, what is clear is that virulence has been linked to sites in env that determine host range or affect Env processing. This correlation was first shown for the avian leukosis virus, for which only subgroups B, D, and F are cytopathic; Dorner and Coffin (4) mapped cytopathicity to env sequences that define subgroup specificity. For the ecotropic mouse gammaretroviruses, rare cytopathic variants have been attributed to env sequences within the receptor binding domain (12, 20, 25). For one of these variants, Moloney ts-1, cytopathicity has been attributed to a single substitution, V25I, in the N terminus of the SU receptor binding domain (25). Our studies indicate that the cytopathicity of two additional isolates, Spl574 and F-S MLV, is due to two different substitutions at the same site in VRA (S82F and S84A). Other studies on the cytopathic Friend isolate TR1.3 have attributed its cytopathic phenotype to another substitution—W102G (20). Mutagenesis and structural analysis (3, 7) have shown that these two VRA sites, S82 and W102, along with D84 are the critical amino acids in receptor binding. These observations taken together suggest that cytopathicity may result from altered virus-receptor interactions that fail to set up superinfection interference. These specific mutations could function by affecting Env protein processing, as shown for V25I (25), or by altering Env stability, transport, and/or direct interaction with the receptor. The involvement of receptor interaction is further suggested by the fact that F-S MLV/Spl574 host range was altered in cells that had different CAT-1 receptors, namely, M. dunni and hamster (Fig. 4B). Within the third extracellular CAT-1 loop that contains the virus binding site, the M. dunni CAT-1 has a single base substitution, V214I, and an insertion of glycine within the YGE segment that has been identified as the receptor binding site (1, 6). The Chinese hamster CAT-1 has two three-residue insertions within this loop flanking one of the two potential glycosylation sites and four additional substitutions, including one that converts YGE to HGE (5). Interestingly, both M. dunni and Chinese hamster cells also differ from cells carrying the prototypical CAT-1 receptor in that their specific virus resistance phenotypes can be eliminated by treatment with tunicamycin, suggesting that glycosylation of the CAT-1 receptor may contribute to the altered host range seen in these cells (5, 28). This type of posttranslational modification could also contribute to the observed differences in infection efficiency among the three different hamster cell lines used in the present study.

The Env domain responsible for fusion is at the amino terminus of TM, and alterations in this region could potentially also contribute to a syncytium-inducing phenotype. We did not, however, sequence the F-S MLV TM, because we consider involvement of this region unlikely for two reasons. First, our previous characterization of the syncytium-inducing isolate Spl574 identified no sequence changes in TM relative to MoMLV (12). Second, the cytopathic phenotype was recapitulated by chimeras containing the 5′ env of F-S MLV and the 3′ env and TM of the noncytopathic virus FrMLV57 (Tables 1 and 2).

In the present experiments, different amino acid substitutions at the same site in Friend and Moloney MLVs produced similar but not identical phenotypes. Cytotoxicity in cultures infected with Spl574 was more severe over time than that observed with F-S MLV (Fig. 3). Differences in host range were also observed: Spl574 showed restricted infectivity for mouse cells other than M. dunni, whereas F-S MLV showed an expanded host range that included efficient infection of hamster as well as all mouse cells. While these differences may result solely from the different residues at this site, phenotypic changes mediated by site-specific mutations can also be modified by residues at other sites. In this case, the pseudotype with S84A is less infectious for hamster cells than the pseudotype with S84A plus S79N. S79N is not responsible for this infectivity, since FBLV has S79N but not S84A and cannot infect hamster cells. Cooperativity among amino acids in CAT-1 receptor function has been noted previously. For example, the importance of W102 in receptor binding was determined only when substitutions at this site were also accompanied by substitutions at D86 (3). Also, introduction of W102G into Fr29-MLV, but not into FrMLV57, produced cytopathic virus (3), and the reciprocal substitution G102W in the cytopathic virus TR1.3 failed to generate infectious virus (20). Further studies on mutants of this type should help determine the basis for these phenotypic differences and help describe the fundamental processes that mediate receptor binding and fusion.

The ability of F-S MLV to infect hamster cells, although at relatively low efficiency, is consistent with a previous study that analyzed chimeras between FrMLV57 and the hamster-tropic FrMLV, PVC-211 (17). This previous study determined that efficient infection of hamster cells was mediated by two substitutions, E116G and E129K (Fig. 4), both of which are needed for efficient infection. Neither of these substitutions is present in F-S MLV. This earlier study additionally showed that chimeras containing a segment of VRA including S79 and S84 are also infectious for hamster cells, although at much lower efficiency, consistent with our observations.

The pathogenic consequences of the polymorphic variation of SU and/or receptor within a single host range subgroup have not been systematically examined for the leukemogenic mouse gammaretroviruses. This is because studies on pathogenesis by the ecotropic MLVs have principally focused on the large recombinations that replace substantial segments of the ecotropic env gene and change receptor usage. For the avian leukosis viruses, on the other hand, small complementary variations in env and the receptor have been shown to account for host range variation and cytopathicity. For other retroviruses, mutant Envs with variant phenotypes have been identified, often after in vivo passage, including cytopathic FeLVs with altered infectivity (22) and simian immunodeficiency virus-human immunodeficiency virus chimeras with altered tropism (11). The present study confirms that small mutational variations in the ecotropic env can also have serious consequences for infectivity and cytopathicity. The role of these Env variants in pathogenesis is being investigated.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Alicia Buckler-White for sequencing. We thank Caroline Ball for editorial assistance in the preparation of the manuscript, Stephan Bour for assistance with submission, and Esther Shaffer for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albritton, L. M., J. W. Kim, L. Tseng, and J. M. Cunningham. 1993. Envelope-binding domain in the cationic amino acid transporter determines the host range of ecotropic murine retroviruses. J. Virol. 67:2091-2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng-Mayer, C., D. Seto, M. Tateno, and J. A. Levy. 1988. Biologic features of HIV-1 that correlate with virulence in the host. Science 240:80-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davey, R. A., Y. Zuo, and J. M. Cunningham. 1999. Identification of a receptor-binding pocket on the envelope protein of Friend murine leukemia virus. J. Virol. 73:3758-3763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dorner, A. J., and J. M. Coffin. 1986. Determinants for receptor interaction and cell killing on the avian retrovirus glycoprotein gp85. Cell 45:365-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eiden, M. V., K. Farrell, and C. A. Wilson. 1994. Glycosylation-dependent inactivation of the ecotropic murine leukemia virus receptor. J. Virol. 68:626-631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eiden, M. V., K. Farrell, J. Warsowe, L. C. Mahan, and C. A. Wilson. 1993. Characterization of a naturally occurring ecotropic receptor that does not facilitate entry of all ecotropic murine retroviruses. J. Virol. 67:4056-4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fass, D., R. A. Davey, C. A. Hamson, P. S. Kim, J. M. Cunningham, and J. M. Berger. 1997. Structure of a murine leukemia virus receptor-binding glycoprotein at 2.0 angstrom resolution. Science 277:1662-1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillin, F. D., D. J. Roufa, A. L. Beaudet, and C. T. Caskey. 1972. 8-Azaguanine resistance in mammalian cells. I. Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase. Genetics 72:239-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartley, J. W., and W. P. Rowe. 1975. Clonal cell lines from a feral mouse embryo which lack host-range restrictions for murine leukemia viruses. Virology 65:128-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirt, B. 1967. Selective extraction of polyoma DNA from infected mouse cell cultures. J. Mol. Biol. 26:365-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imamichi, H., T. Igarashi, T. Imamichi, O. K. Donau, Y. Endo, Y. Nishimura, R. L. Willey, A. F. Suffredini, H. C. Lane, and M. M. Martin. 2002. Amino acid deletions are introduced into the V2 region of gp120 during independent pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus/HIV chimeric virus (SHIV) infections of rhesus monkeys generating variants that are macrophage tropic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:13813-13818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung, Y. T., and C. A. Kozak. 2003. Generation of novel syncytium-inducing and host range variants of ecotropic Moloney murine leukemia virus in Mus spicilegus. J. Virol. 77:5065-5072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kai, K., and T. Furuta. 1984. Isolation of paralysis-inducing murine leukemia viruses from Friend virus passaged in rats. J. Virol. 50:970-973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koch, W., W. Zimmerman, A. Oliff, and R. Friedrich. 1984. Molecular analysis of the envelope gene and long terminal repeat of Friend mink cell focus-inducing virus: implications for the functions of these sequences. J. Virol. 49:828-840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lander, M. R., and S. K. Chattopadhyay. 1984. A Mus dunni cell line that lacks sequences closely related to endogenous murine leukemia viruses and can be infected by ecotropic, amphotropic, xenotropic, and mink cell focus-forming viruses. J. Virol. 52:695-698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masuda, M., C. A. Hanson, W. G. Alvord, P. M. Hoffman, S. K. Ruscetti, and M. Masuda. 1996. Effects of subtle changes in the SU protein of ecotropic murine leukemia virus on its brain capillary endothelial cell tropism and interference properties. Virology 215:142-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masuda, M., M. Masuda, C. A. Hanson, P. M. Hoffman, and S. K. Ruscetti. 1996. Analysis of the unique hamster cell tropism of ecotropic murine leukemia virus PVC-211. J. Virol. 70:8534-8539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller, D. G., and A. D. Miller. 1992. Tunicamycin treatment of CHO cells abrogates multiple blocks to retrovirus infection, one of which is due to a secreted inhibitor. J. Virol. 66:78-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliff, A. I., G. L. Hager, E. H. Chang, E. M. Scolnick, H. W. Chan, and D. R. Lowy. 1980. Transfection of molecularly cloned Friend murine leukemia virus DNA yields a highly leukemogenic helper-independent type C virus. J. Virol. 33:475-486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park, B. H., B. Matuschke, E. Lavi, and G. N. Gaulton. 1994. A point mutation in the env gene of a murine leukemia virus induces syncytium formation and neurologic disease. J. Virol. 68:7516-7524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Remington, M. P., P. M. Hoffman, S. K. Ruscetti, and M. Masuda. 1992. Complete nucleotide sequence of a neuropathogenic variant of Friend murine leukemia virus PVC-211. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rohn, J. L., M. S. Moser, S. R. Gwynn, D. N. Baldwin, and J. Overbaugh. 1998. In vivo evolution of a novel, syncytium-inducing and cytopathic feline leukemia virus variant. J. Virol. 72:2686-2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowe, W. P., W. E. Pugh, and J. W. Hartley. 1970. Plaque assay techniques for murine leukemia viruses. Virology 42:1136-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shinnick, T. M., R. A. Lerner, and J. G. Sutcliffe. 1981. Nucleotide sequence of Moloney murine leukaemia virus. Nature 293:543-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szurek, P. F., P. H. Yuen, J. K. Ball, and P. K. Y. Wong. 1990. A Val-25-to-Ile substitution in the envelope precursor polyprotein, gPr80env, is responsible for the temperature sensitivity, inefficient processing of gPr80env, and neurovirulence of ts1, a mutant of Moloney murine leukemia virus TB. J. Virol. 64:467-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Temin, H. M. 1988. Mechanisms of cell killing/cytopathic effects by nonhuman retroviruses. Rev. Infect. Dis. 10:399-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weller, S. K., and H. M. Temin. 1981. Cell killing by avian leukosis viruses. J. Virol. 39:713-721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson, C. A., and M. V. Eiden. 1991. Viral and cellular factors governing hamster cell infection by murine and gibbon ape leukemia viruses. J. Virol. 65:5975-5982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshimura, F. K., T. Wang, and S. Nanua. 2001. Mink cell focus-forming murine leukemia virus killing of mink cells involves apoptosis and superinfection. J. Virol. 75:6007-6015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]