Abstract

Elucidation of the kinetics of exposure of neutralizing epitopes on the envelope of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) during the course of infection may provide key information about how HIV escapes the immune system or why its envelope is such a poor immunogen to induce broadly efficient neutralizing antibodies. We analyzed the kinetics of exposure of the epitopes corresponding to the broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies immunoglobulin G1b12 (IgG1b12), 2G12, and 2F5 at the quasispecies level during infection. We studied the antigenicity and sequences of 94 full-length envelope clones present during primary infection and at least 4 years later in four HIV-1 clade B-infected patients. No or only minor exposure differences were observed for the 2F5 and IgG1b12 epitopes between the early and late clones. Conversely, the envelope glycoproteins of the HIV-1 quasispecies present during primary infection did not expose the 2G12 neutralizing epitope, unlike those present after several years in three of the four patients. Sequence analysis revealed major differences at potential N-linked glycosylation sites between early and late clones, particularly at positions known to be important for 2G12 binding. Our study, in natural mutants, confirms that the glycosylation sites N295, N332, and N392 are essential for 2G12 binding. This study demonstrates the relationship between the evolving “glycan shield ” of HIV and the kinetics of exposure of the 2G12 epitope during the course of natural infection.

Until recently, it was thought that low levels of neutralizing antibodies to autologous viruses develop slowly throughout human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection (6, 7, 26, 27, 36). However, two recent studies based on elegant recombinant virus assays provided major new information about the kinetics of the neutralizing antibody response to HIV (39, 49). It is now clear that the autologous neutralizing response is generally strong and develops rapidly. However, the neutralizing antibody response exerts a selective pressure that continuously drives the evolution of neutralizing escape mutants, allowing them to persist in the host. This strong, early autologous neutralizing response is generally inefficient against heterologous viruses (39, 49). Broadly neutralizing antibodies, which are able to neutralize a broad spectrum of primary isolates, are rarely found in HIV-1-infected individuals (3, 7, 26). When detected, they appear late, at least several years after primary infection, mainly in long-term asymptomatic patients (11, 52). A few human monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) with broadly neutralizing activities have been isolated from such individuals (8, 12, 13, 14, 25, 28, 29, 45, 47, 48). Among them, three major MAbs have been characterized in depth: immunoglobulin G1b12 (IgG1b12), 2G12, and 2F5. The epitopes recognized by IgG1b12 and 2G12 are located on the surface envelope glycoprotein gp120. IgG1b12 binds to an epitope overlapping the CD4 receptor site (32, 40, 43, 53), whereas 2G12 binds to a carbohydrate-dependent epitope involving the C2 and C3 regions around the base of the V3 loop, the C4 region, and the V4 loop (4, 10, 42, 48). The carbohydrate attachment sites cluster on the “silent face” of gp120 (21, 22, 44, 50, 51). The 2F5 MAb binds to an epitope including a linear motif of 16 amino acid residues located in the ectodomain of the transmembrane glycoprotein gp41 (20, 30, 33, 38, 54). It is important to focus on these three MAbs, not only because they have potent neutralizing activities against a broad range of primary isolates in vitro but also because they are able to confer sterilizing immunity in animal models when passively transferred at high concentrations, alone or in combination, before an infectious challenge (2, 15, 17, 23, 24, 34, 35, 37).

The frequency and dynamics of exposure of the three corresponding epitopes on the viral envelope glycoprotein during the natural infection course are not known. To improve our understanding of the late appearance of broadly neutralizing antibodies, we hypothesized that these major epitopes are absent or weakly exposed on the envelopes of viruses present during primary infection and become better exposed several months or years postinfection due to continuous selective pressure on more exposed regions of the envelope. Therefore, we monitored the exposure of the IgG1b12, 2G12, and 2F5 epitopes on the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins at the quasispecies level in four patients from primary infection until at least 4 years later. At least 14 recombinant envelope glycoproteins were produced from viral quasispecies present at early and late stages of infection for each patient. Antigenic characterization was performed for all these recombinant glycoproteins, and the corresponding env genes were sequenced. Our hypothesis was confirmed only for the 2G12 epitope, which was not found on the envelope glycoproteins derived from early viruses but was highly exposed on envelope glycoproteins from late viruses from three of the four patients. This antigenic property was linked to changes in potential N-linked glycosylation sites within gp120, in accordance with the recent theory of an evolving “glycan shield ” as a mechanism contributing to HIV-1 persistence (49).

(This work was presented in part at the Third International AIDS Vaccine Symposium, New York, N.Y., 17 to 20 September 2003.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and samples.

Four HIV-1 clade B-infected men were selected from a cohort of patients identified at the time of symptomatic primary infection in the Department of Infectious Diseases of the Croix-Rousse Hospital, Lyon, France (1). They all claimed to have had nonprotected sexual contacts during the month before the onset of symptoms. All the patients signed informed consent forms. Study protocols were approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the Hospices Civils de Lyon. Primary infection was diagnosed by quantitative detection of both HIV-1 RNA (Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor test; Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, N.J.) and p24 antigen (Vidas HIV p24 test; bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) on sequential plasma samples. The antibody status was determined on the same samples by using a third-generation enzyme immunoassay (Vidas EIA; bioMérieux) and Western blot analysis (Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) to confirm seroconversion. Two peripheral blood samples were selected for each patient, one collected at the time of primary infection and the other collected at least 4 years later. Clinical, virological, and serological characteristics of the patients at the time at which the early and late samples were collected are summarized in Table 1. One of the patients received early treatment consisting of an association of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and was still under such a regimen 6 years later (patient 309).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patients at time of blood sample collection

| Patient (risk factor) | Type and date of blood sample | Viral load (log copies/ml) | CD4 (cells/mm3) | ELISA result | Western blot result | Treatmente |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 133 (MSMa) | A, 14 September 1992 | 6.7 | 159 | Negative | Negative | No |

| U, 3 October 1997 | 3.2 | 350 | No | |||

| 153 (MSM) | A, 3 May 1993 | 5.1 | 365 | Positive | Indeterminatec | No |

| O, 3 September 1999 | 3.3 | 467 | No | |||

| 159 (MSM) | A, 16 July 1993 | 5.7 | NDd | Negative | Negative | No |

| F, 24 July 1997 | 4.1 | 495 | No | |||

| 309 (Hetb) | A, 11 May 1994 | 6.6 | 224 | Negative | Negative | ZDV-ddl |

| AC, 8 June 2000 | 3.5 | 561 | ZDV-3TC |

MSM, homosexual man.

Het, heterosexual transmission.

Indeterminate, presence of antibodies to only gp160.

ND, not determined.

ZDV, zidovudine; ddI, didanosine; 3TC, lamivudine.

Nucleic acid extraction, PCR, and plasmid constructions.

After extraction of genomic DNA from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of each sample (QIAamp DNA Blood Midi kit; Qiagen SA, Courtaboeuf, France), the full-length env gene was amplified by nested PCR with a proofreading Taq polymerase (PfuTurbo DNA polymerase; Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), as previously described (5). For samples 133A, 153A, and 159A, the outer primer pair used was env1 (5′-AATAGCAATAGTTGTGTGGTCC-3′) and env2 (5′-GCCTCTCTCTTCACAATCTCA-3′) and the inner primer pair was env3 (5′-GAAGACAGTGGCAATGAGAGTG-3′) and env4 (5′-CTCTGGACCTTTTTGTACCTC-3′) (1). For samples 133U, 153O, 159F, and 309AC, the outer primer pair was MT1 (5′-GCTTAGGCATYTCCTATGGCA-3′) and MT2 (5′-GCTCCCTTRTAAGTCATTGGTC-3′) and the inner primer pair was SFV5 (5′-GGGATCCATCTTATAGCAAAGCCCTTTCCAA-3′) and SFV3 (5′-AGGATCCGAAGACAGGCACCATGAGAGTGAAGG-3′) (5). For sample 309A, the outer primer pair was env1 and env2 and the inner primer pair was SFV3 and SFV5. All PCR products were cloned into pCR2.1 (Topo TA cloning kit; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). At least 14 pCR2.1-env clones were selected from each sample to obtain the best representation of the predominant proviruses in both periods. The env genes were then subcloned into the Semliki Forest virus-derived expression vector (pSFV1; Invitrogen) as previously described (5).

Production of recombinant envelope glycoproteins.

All pSFV1-env vectors were used as templates for the in vitro synthesis of recombinant RNAs encoding the full-length gp160 glycoproteins. The pSFV3 vector encoding the β-galactosidase protein (Invitrogen) was used in each experiment as a negative control. The expression vectors pSFV-HxB2 and pSFV-MN, encoding the envelope glycoproteins of the well-characterized laboratory-adapted strains HxB2 and MN, respectively, were used as positive controls because they were known to expose the three neutralizing epitopes (5). To produce recombinant glycoproteins, BHK-21 cells were grown in minimal essential medium supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, tryptose phosphate, and fetal bovine serum (5%) and then electroporated (350 V, 750 μF, 1.2 × 107 cells per transfection) with 5 μg of each recombinant RNA. Transfected cells were plated in 75-cm2 tissue culture flasks and incubated for 16 h at 37°C. The culture supernatants were collected and kept frozen at −80°C until use for soluble CD4 (sCD4) binding and antigenicity studies. The cells were lysed using 0.5% Nonidet P-40 in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl; 2 ml/6 × 106 cells). The cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min and kept frozen at −80°C until use. The presence of the glycoproteins was checked by Western blotting. The cell lysates were diluted 1:5 in phosphate-buffered saline and loaded onto a sodium dodecyl sulfate-8% polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and probed overnight with a 1:500 dilution of a pool of sera from 10 HIV-1-infected patients. Bound antibodies were revealed using a peroxidase-conjugated goat F(ab′)2 anti-human Ig (Biosource, Camarillo, Calif.) followed by a chemiluminescent substrate (ECL kit; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, N.J.).

ELISA.

The antigenicity of recombinant envelope glycoproteins was analyzed using a modified version of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) procedure initially described by Moore et al. (28). Microtiter plates (CEB, Nemours, France) were coated overnight at 4°C with 5 μg of sheep anti-gp120 polyclonal antibody D7324 (Aalto Bioreagents Ltd., Dublin, Ireland)/ml diluted in TBS. Subsequent incubation steps were performed at room temperature. The plates were washed three times with TBS containing 0.5% Tween 20 (TBS-T). Nonspecific binding sites were saturated by incubation for 1 h with 200 μl of 2% newborn calf serum in TBS. Envelope glycoproteins were captured on the solid phase by incubation for 2 h at room temperature with 100 μl of culture supernatant for gp120 or 100 μl of a 1:5 dilution of cell lysate for gp160. The plates were washed three times with TBS-T. The captured envelope proteins were then probed with MAbs to neutralizing epitopes (IgG1b12, 2G12, and 2F5) and polyclonal antibodies present in a pool of sera from HIV-1-infected individuals (HIV+ pool). The neutralizing MAbs were tested at 2.6 μg/ml for IgG1b12, 4 μg/ml for 2F5, and 0.5 μg/ml for 2G12 (100 μl per well). MAb 2F5 was used to probe only cell lysates because it did not bind gp120 released into the supernatant. The MAbs were diluted in TBS containing 0.5% Tween 20, 20% sheep serum, and 10% newborn calf serum (TBS-TSN). The HIV+ pool was prepared with sera from 10 patients infected by subtype B variants. It was diluted 1:4,000 in TBS-TSN, and 100 μl of this dilution was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 1 h and washed five times with TBS-T. A peroxidase-conjugated goat F(ab′)2 anti-human Ig (Biosource) diluted 1:1,000 in TBS-TSN was then added (100 μl/well). The plates were incubated for 30 min and washed three times with TBS-T, and then 100 μl of a mixture of H2O2 and o-phenylenediamine (Sigma Fast; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was added. We allowed the color reaction to develop for 30 min at room temperature in the dark and then stopped it by adding 50 μl of 2 N H2SO4. We then determined absorbance (A) at 490 nm. The net absorbance value was calculated by subtracting the absorbance obtained with the Semliki Forest virus-β-galactosidase negative control. As slight differences in the expression levels of each clone might introduce artifactual differences in binding properties, the results were normalized by using a binding index: absorbance with MAb/absorbance with HIV+ pool.

The sCD4 binding capacity of each envelope glycoprotein was analyzed with a similar ELISA. Each envelope glycoprotein was captured on D7324-coated plates as described above and incubated for 2 h at room temperature with 100 μl of sCD4 (1 μg/ml) (National Institute for Biological Standards and Control [NIBSC], Potters Bar, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom) diluted in TBS-TSN. After five washes with TBS-T, the wells were filled with 100 μl of anti-CD4 MAb (0.5 μg/ml) (L120.3; NIBSC) diluted in TBS-TSN. The plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature and washed five times with TBS-T, and a peroxidase-conjugated goat F(ab′)2 anti-mouse Ig (Biosource), diluted 1:500 in TBS-TSN, was then added (100 μl/well). The plates were incubated for 30 min at room temperature and washed three times with TBS-T before 100 μl of the substrate was added. After color development, the absorbance was measured as described above. The net absorbance value was calculated by subtracting the absorbance obtained with the Semliki Forest virus-β-galactosidase negative control. The binding index, defined as absorbance with sCD4/absorbance with HIV+ pool, was calculated for each clone.

A semiquantitative scale was used to facilitate comparison of the various clones. It was based on the value of the binding index (−, <0.1; +, 0.1 to 0.5; ++, 0.5 to 1; +++, >1).

Sequence analysis.

All env clones inserted in pSFV were sequenced using a set of env-specific internal primers, according to the dye terminator cycle sequencing protocol (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Nucleotide sequences were assembled with the BioEdit package, version 5.0.9 (16). DNA sequences and deduced amino acid sequences from both early and late stage for each patient were aligned by using Clustal W (46) with manual correction and formatted for publication by using SeqPublish (https://hiv-web.lanl.gov/content/hiv-db/SeqPublish/seqpublish.html). Phylogenetic analysis and neighbor-joining tree reconstructions were performed by the neighbor-joining method (41) with MEGA version 2.1 (19). The distance matrix was calculated with the two-parameter Kimura algorithm (transition-to-transversion ratio of 2.0). Approximate confidence limits for individual branches were assigned by bootstrap resampling with 1,000 replicates. Net charges of the V3 loop (amino acids in positions 296 to 331 relative to HxB2 numbering) were calculated at physiological pH based on basic amino acids (+1 charge with lysine and arginine) and acidic amino acids (−1 charge with aspartic and glutamic acids). Potential N-linked glycosylation sites were identified by using N-Glycosite (https://hiv.lanl.gov/content/hiv-db/GLYCOSITE/glycosite.html).

Statistical analysis.

The comparison between early and late clones was done using the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All full-length env sequences have been submitted to GenBank and assigned accession no. AY535425 through AY535518.

RESULTS

Antigenic profiles and sCD4 binding of env proteins from early and late viral populations.

A total of 14 early and 17 late env clones were obtained for patient 133, 18 early and 19 late clones were obtained for patient 153, 18 early and 19 late clones were obtained for patient 159, and 17 early and 19 late clones were obtained for patient 309. Recombinant glycoproteins (gp120 and gp160) were produced from all these env clones. Antigenicity was analyzed by ELISA with the three MAbs IgG1b12, 2G12, and 2F5 and a pool of sera from HIV-1-infected patients as a control. Clones were considered defective if no gp120 was detected in the culture supernatant of transfected cells. The abnormality of these clones was confirmed by Western blotting (abnormal size) and sequence analysis (see below). Between 7 of 37 (18.9%, patient 153) and 21 of 36 (58.3%, patient 309) clones were defective (Table 2). The 47 defective clones were not included in the subsequent analysis. Five additional clones with premature stop codons in the transmembrane part of the envelope were kept for antigenic analysis because no abnormal binding reactivity was observed with the HIV+ pool and sCD4 (see below and Fig. 4).

TABLE 2.

Antigenic profiles and sCD4 binding abilities of the various envelope clones isolated from early and late samples from four patientsa

| Patient no., respective no. of early and late clones, and clone type | No. of clones (%b)

|

Antigenic profile

|

sCD4 bindingc

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | Late | b12 | 2G12 | 2F5 | Early | Late | |

| 133 (14, 17) | |||||||

| gp120 | 7 (87.5) | − | − | 7 | |||

| 1 (12.5) | + | − | 1 | ||||

| 14 (100) | − | +++ | 12 | ||||

| gp160 | 1 (12.5) | + | − | − | 1 | ||

| 1 (12.5) | − | − | − | 1 | |||

| 6 (75.0) | − | − | + | 6 | |||

| 2 (14.0) | − | ++ | − | 2 | |||

| 12 (86.0) | − | +++ | − | 10 | |||

| Defective | 6 | 3 | |||||

| 153 (18, 19) | |||||||

| gp120 | 1 (6.8) | 1 (6.8) | − | − | 1 | ||

| 3 (20.4) | + | − | 3 | ||||

| 10 (66.0) | ++ | − | 9 | ||||

| 1 (6.8) | 1 (6.8) | +++ | − | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 (6.8) | − | ++ | |||||

| 1 (6.8) | − | +++ | |||||

| 5 (33.0) | + | +++ | 5 | ||||

| 5 (33.0) | ++ | +++ | 4 | ||||

| 1 (6.8) | +++ | ++ | 1 | ||||

| gp160 | 1 (6.8) | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| 1 (6.8) | + | − | − | 1 | |||

| 6 (40.0) | + | − | + | 4 | |||

| 7 (46.4) | 1 (6.8) | ++ | − | + | 7 | 1 | |

| 1 (6.8) | − | − | + | ||||

| 1 (6.8) | − | + | + | ||||

| 1 (6.8) | − | ++ | − | 1 | |||

| 5 (33.0) | − | ++ | + | 4 | |||

| 2 (13.1) | − | +++ | + | 1 | |||

| 1 (6.8) | − | + | +++ | ||||

| 2 (13.1) | + | ++ | + | 2 | |||

| 1 (6.8) | + | +++ | + | 1 | |||

| Defective | 3 | 4 | |||||

| 159 (18, 19) | |||||||

| gp120 | 1 (6.8) | 1 (8.3) | − | +++ | 1 | 1 | |

| 1 (6.8) | 1 (8.3) | + | + | 1 | 1 | ||

| 3 (20.4) | 2 (16.6) | + | +++ | 2 | 2 | ||

| 1 (6.8) | ++ | − | 1 | ||||

| 8 (52.4) | 7 (58.5) | ++ | +++ | 8 | 7 | ||

| 1 (6.8) | +++ | +++ | 1 | ||||

| 1 (8.3) | − | ++ | 1 | ||||

| gp160 | 3 (20.4) | − | + | ++ | |||

| 1 (6.8) | + | − | ++ | 1 | |||

| 1 (6.8) | + | ++ | − | 1 | |||

| 1 (6.8) | + | +++ | + | ||||

| 1 (6.8) | ++ | − | + | ||||

| 2 (13.6) | ++ | ++ | + | 2 | |||

| 1 (6.8) | ++ | ++ | ++ | 1 | |||

| 4 (25.2) | ++ | +++ | + | 4 | |||

| 1 (6.8) | ++ | +++ | ++ | 1 | |||

| 2 (16.6) | − | − | + | ||||

| 3 (25.0) | − | + | + | ||||

| 5 (41.8) | + | + | + | 5 | |||

| 1 (8.3) | + | + | ++ | 1 | |||

| 1 (8.3) | + | ++ | ++ | 1 | |||

| Defective | 3 | 7 | |||||

| 309 (17, 19) | |||||||

| gp120 | 1 (12.5) | − | − | ||||

| 7 (87.5) | + | − | 7 | ||||

| 1 (14.3) | − | ++ | |||||

| 4 (57.1) | + | ++ | 1 | ||||

| 1 (14.3) | ++ | − | 1 | ||||

| 1 (14.3) | − | ++ | 1 | ||||

| gp160 | 1 (12.5) | − | − | − | |||

| 6 (75.0) | + | − | + | 6 | |||

| 1 (12.5) | + | − | ++ | 1 | |||

| 4 (57.1) | − | + | + | ||||

| 1 (14.3) | + | − | + | 1 | |||

| 1 (14.3) | + | + | + | 1 | |||

| 1 (14.3) | + | ++ | + | 1 | |||

| Defective | 9 | 12 | |||||

The semiquantitative analysis of the MAb binding properties was based on the binding index (−, <0.1; +, 0.1 to 0.5; ++, 0.5 to 1; +++, >1).

Percentage of clones with a given antigenic profile among the nondefective clones.

Number of clones binding sCD4.

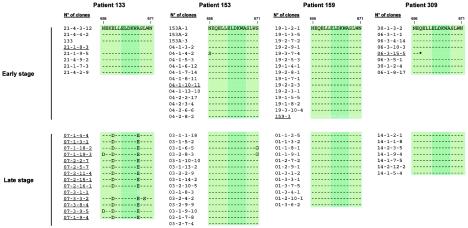

FIG. 4.

Amino acid sequences including the linear 2F5 epitope among all clones isolated from the four patients and correlation with 2F5 binding. The core epitope is indicated in dark green. Amino acid numbers correspond to the HxB2 sequence (18). Clones that did not bind 2F5 are underlined. The asterisk corresponds to a stop codon.

Semiquantitative analysis of MAb binding allowed us to compare the antigenic profiles of the clones. The antigenic profiles of the viral populations were quite homogeneous for patient 133 (Table 2). However, the antigenic profiles of early and late clones were highly divergent. The major difference between early and late envelopes was the lack of 2G12 binding to all early clones, whereas 2G12 strongly bound to all late clones, for both gp120 and gp160. A greater diversity of antigenic profiles was observed for late clones than for early clones in patients 153 and 309 (Table 2). In addition, similarly to the situation for patient 133, 2G12 strongly bound most of the env clones from the late viral population of these two patients but none of the early envelope proteins, for both gp120 and gp160. No such switch in exposure of the 2G12 epitope between early and late clones was observed for the fourth patient, 159 (Table 2); his early viral population was already highly heterogeneous and 2G12 reactive. In contrast to 2G12, both IgG1b12 and 2F5 bound most of the early and late clones, except for those from patient 133.

Almost all the early and late clones from the four patients bound sCD4 (Table 2). Eight of the 12 clones that did not bind CD4 did not bind IgG1b12, which is not surprising, as the b12 epitope overlaps the CD4 binding site.

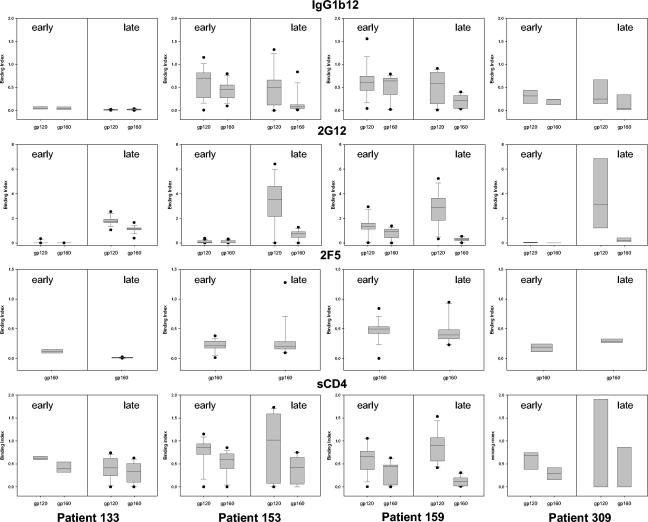

We next carried out a quantitative analysis of the binding index of the three MAbs and sCD4 for the early and late glycoproteins (Fig. 1). The distributions of the binding indices of the late and early clones were compared using the Wilcoxon signed rank test for each ligand, i.e., MAb or sCD4. No or only minor differences were observed between early and late clones for binding of IgG1b12, 2F5, and sCD4 to both gp120 and gp160 for each patient. In contrast, major differences were found with MAb 2G12 for patients 133, 153, and 309. For these three patients, the binding index increased significantly between early and late clones for both gp120 (P = 0.0001, P < 0.0001, and P = 0.003, respectively) and gp160 (P = 0.0001, P = 0.0002, and P = 0.005, respectively). As indicated above and in Table 2, early clones from patient 159 already exposed the 2G12 epitope, and accordingly no significant increase in binding index was observed in the late clones.

FIG. 1.

Antigenic profiles and sCD4 binding abilities of the recombinant envelope glycoproteins (gp120 and gp160) derived from the early and late clones for each patient. The four patients are presented from left to right. The binding indices for IgG1b12, 2G12, 2F5, and sCD4 are presented from top to bottom. Each frame shows the distribution of the binding index for both gp120 and gp160 of early clones (left panels) and late clones (right panels). For each distribution, the horizontal lines represent the 10th, 25th, 50th (median), 75th, and 90th percentiles.

Phylogenetic analysis of full-length env sequences.

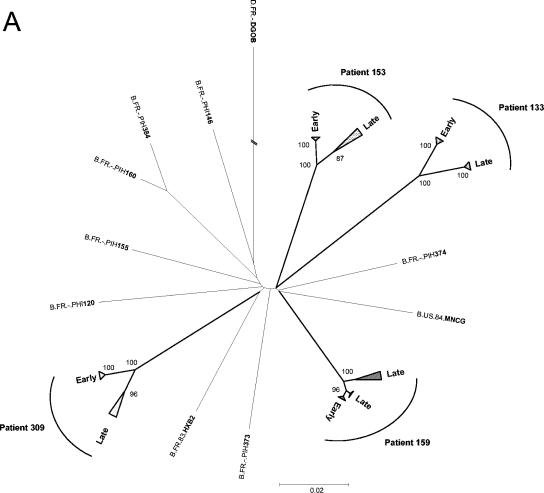

A phylogenetic tree was constructed on the basis of the 94 full-length env sequences isolated at early and late stages of infection from the four patients, 133 (n = 22), 153 (n = 30), 159 (n = 27), and 309 (n = 15) (Fig. 2). Eleven additional entire env sequences obtained previously from the proviral DNA isolated during primary infection from our four patients (PIH133, PIH153, PIH159, and PIH309) and seven other patients from the same cohort were also included as controls (1). As expected, all env sequences from a given patient were clearly distinct from those of other patients, with branches supported by high bootstrap values (100%). For each patient, viral populations from the same stage of infection clustered together (bootstrap values from 87 to 100%). The only exception was for patient 159, for whom the late viral population was separated into two different groups, one very close to the early viral population and the other more distantly related. For patient 133, all the clones from the early stage formed a tight cluster in one branch and all those from the late stage formed a tight cluster in another branch. This indicates strong homogeneity in each distinct viral population present at these two stages (Fig. 2B). env clones from patients 153 (Fig. 2C) and 309 (Fig. 2E) presented a more expected evolution, with a tight clustering of the early clones and a more heterogeneous distribution of the late clones (four and two groups or subclusters of clones, respectively). The phylogenetic analysis of sequences from patient 159 revealed a quite different distribution, most of the late clones being tightly clustered next to the early clones, at a short genetic distance (Fig. 2D). Only three late clones were separated from the others, indicative of a more divergent genetic evolution. As expected, the sequences of PIH133, PIH153, PIH159, and PIH309, which were obtained previously and independently (1), clustered with the early clones of each corresponding patient. Among the 94 env sequences, six pairs of clones were genetically identical (three pairs for patient 153 and three pairs for patient 159). The phylogenetic analysis provided information that fitted perfectly the distribution of the antigenic profiles of the clones derived from each patient (Table 2). Indeed, early and late clones from patient 133 were relatively homogeneous although divergent among each group: they were located on two phylogenetically related branches, with a major difference in 2G12 binding. Late clones from patients 153 and 309 were more heterogeneous than early clones were, both genetically and antigenically, again with a major antigenic difference in 2G12 binding. All the early clones and most of the late clones from patient 159 were closely related genetically. They displayed similar antigenic profiles, particularly exposing the 2G12 epitope at both stages.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of early and late full-length HIV-1 envelope gene sequences from the four patients. A distance scale is given for each neighbor-joining tree. Bootstrap values are expressed as percentages per 1,000 replicates, and only values above 80% are indicated on nodes. (A) Neighbor-joining tree including 94 full-length env sequences, 11 other clade B sequences obtained previously from proviral DNA isolated at the time of primary infection from our four patients (PIH133, PIH153, PIH159, and PIH309) and seven other patients (PIH120, PIH146, PIH155, PIH160, PIH373, PIH374, and PIH384) from the same cohort (accession numbers AF041125 to AF041135 [1]), and the two reference sequences HxB2 and MN (accession numbers AF033819 and M17449, respectively). The sequence of the env gene from a clade D virus (DGOB) was used as an outlier. Triangles correspond to clusters of early or late clones. (B to E) Details for patients 133 (B), 153 (C), 159 (D), and 309 (E). The different groups of late clones are indicated by circled numbers.

Global analysis of the full-length envelope sequences.

We analyzed the deduced amino acid sequences of the full-length envelope glycoproteins. Potential inactivating mutations (i.e., premature stop codons and/or frameshifts) were observed in the 47 env clones considered defective based on the failure to detect gp120 in the culture supernatants. As expected from the phylogenetic analysis, the amino acid sequences of the early clones from patient 133 were quite homogeneous. Only 20 sporadic mutations were found among the eight full-length early sequences. Although the late viral population of patient 133 presented 44 sporadic substitutions, the 14 late sequences were quite homogeneous. Compared to the early viral sequences, all the late clones presented 53 common fixed substitutions scattered throughout the protein. Major differences with early clones were noted in the variable loops, with the insertion of 11 and 6 amino acids in V1 and V4, respectively, in all late clones. The global positive charge of the V3 loop (positions 11 to 25) increased between early clones (+2) and late clones (+5), possibly reflecting a change in coreceptor usage. The deduced amino acid sequences of early clones from patients 153 and 309 were also highly homogeneous. A total of 39 and 14 sporadic changes were found among the 15 and 8 full-length early clones of patients 153 and 309, respectively. The groups of late clones previously identified in the phylogenetic analysis were confirmed by amino acid sequences, especially within the variable loops (four and two groups for patients 153 and 309, respectively). The groups of late clones from patient 153 contained between 16 and 31 single changes. Twenty conserved mutations were noted among the four groups. As in late clones from patient 133, the lengths of variable regions were modified in all late clones, especially in V1 (increase of 1 to 13 amino acid residues) and V4 (deletion of 5 amino acid residues). There were between 12 and 15 sporadic mutated sites for the two groups of late clones from patient 309. Twenty-seven fixed changes were noted among the seven late sequences. Modifications of the length of variable regions were also observed in V2 (increase of 5 amino acid residues), V4 (decrease of 4 amino acid residues), and V5 (increase of 4 or 6 amino acid residues). Changes in the global positive charge of the V3 loop occurred only for patient 153 (+4 for early clones and +2 to +5 for late clones). The global positive charge of this loop remained constant in early and late clones in patient 309 (+3). As expected from the phylogenetic data, most of the late clones from patient 159 were quite similar to the early clones, except the three late clones (01-3-4-1, 01-2-10-1, and 01-3-6-2) corresponding to groups 2, 3, and 4, respectively (Fig. 2D). Only one fixed mutation was found in all the late clones compared to the early clones. Groups 2, 3, and 4 of late clones were quite different, especially in variable loops and V3 charge, confirming their genetic drift. Late clone 01-2-10-1 was highly different from the others, with 41 mutations compared to early clones and late clones from group 1. Again, major differences were found in variable loops, with the insertion of 13 amino acid residues in V1 and the deletion of 6 and 3 amino acid residues in V4 and V5, respectively. The global charge of the V3 loop of this clone was also different (+4 versus +2 for early clones and late clones from group 1). Clones 01-3-4-1 and 01-3-6-2 appeared to be two different recombinant forms between the late clones of group 1 and clone 01-2-10-1. The sequence of clone 01-3-4-1 was similar to that of clone 01-2-10-1 from V3 to the C terminus, and the sequence of clone 01-3-6-2 was similar to that of clone 01-2-10-1 from the N terminus to V2.

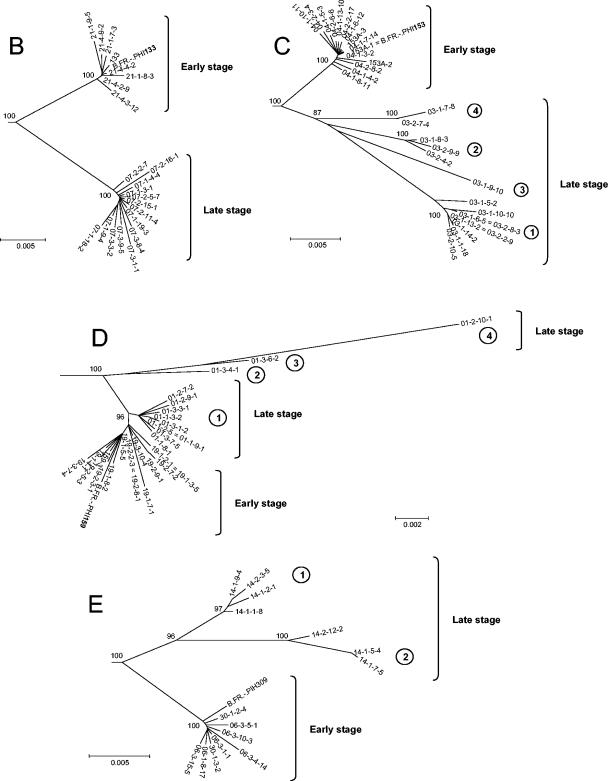

A significant difference in the number of potential N-linked glycosylation sites was observed between the early and late viral populations for three of the four patients. The early clones from patient 133 presented a median of 28 potential N-linked glycosylation sites (range, 26 to 29) versus 31 for the late viral population (range, 30 to 33; P < 0.0002, Wilcoxon signed rank test). Similar results were observed for patients 153 and 309, with a median of 29 potential sites (range, 28 to 29) among the early clones versus 31 (range, 31 to 33; P < 0.0001) for the late clones of patient 153 and a median of 25 (range, 24 to 29) for early clones versus 31 (range, 30 to 33; P < 0.002) for the late clones of patient 309. For these three patients, modifications in the N-glycosylation consensus sequences (sequons; NXS or NXT where X represents any amino acid residue except proline) between early and late clones were mainly located within the variable regions of gp120: V1 (+2 sites) and V4 (+1 site) for patient 133; V1 (+2 sites) for subclusters 2 to 4 of patient 153; and V1 (+1 site), V2 (+1 to +3 sites), V4 (+1 to +2 sites) and V5 (+1 site) for patient 309 (Fig. 3). However, mutations that created potential N-linked glycosylation sites were also observed in constant domains of late clones: I297T in C2 (+1 site) for patient 133, P291T in C2 (+1 site) and S332N in C3 (+1 site) for patient 153, and D332N in C3 (+1 site) for patient 309. In addition to the increased sequon number, some modifications in the global repartition of potential N-linked glycosylation sites on gp120 were observed among the late clones (Fig. 3). For instance, one sequon that was present in the V2 region of early clones of patient 133 had disappeared in the late clones due to a T162A mutation. For these same late clones, the fixed substitution N334S in the C3 domain shifted the potential site upstream by 2 amino acid residues compared to the early clones. For patient 153, the deletion of 5 amino acid residues in the V4 loop of all the late clones resulted in the disappearance of two potential glycosylation sites, and the N151Y mutation in V1 of late clones of group 2 and the T394I mutation in V4 of late clones of group 4 both resulted in the loss of one sequon.

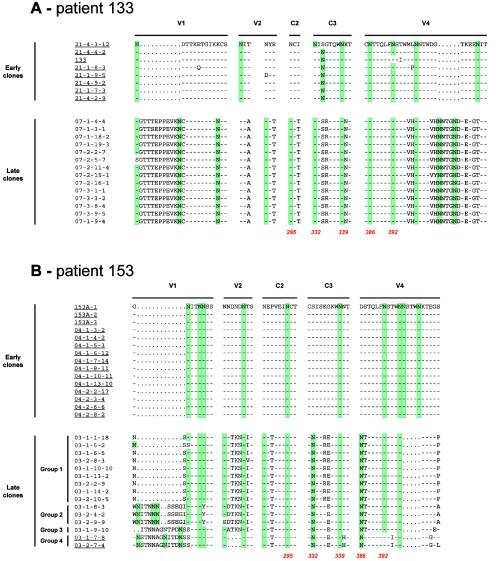

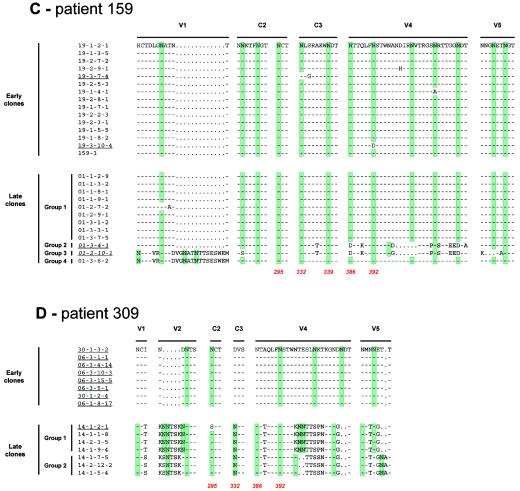

FIG. 3.

Location of the modifications affecting potential N-linked glycosylation sites within the envelope glycoproteins of early and late clones from each patient and correlation with 2G12 binding. For clarity, regions of the envelope that contain N-linked glycosylation sites that were conserved between early and late clones are not shown. Potential N-linked glycosylation sites are highlighted in green. N-linked glycosylation sites implicated in the 2G12 epitope are indicated in red, with amino acid numbers corresponding to the HxB2 sequence (18). Clones that did not bind 2G12 are underlined, and those that weakly bound 2G12 are in italics and underlined.

In contrast to these three patients, no major differences in potential N-glycosylation sites were found between early and late clones of patient 159 (Fig. 3). The median number of sites was 31 for both early clones (range, 30 to 31) and late clones (range, 30 to 32) of group 1. They were conserved at the same position. Only late clones from group 2 (29 sequons), group 3 (29 sequons), and group 4 (34 sequons) presented modifications in the distribution of potential N-linked glycosylation sites (Fig. 3).

Relationship between amino acid sequences and antigenicity.

The full-length sequences of the 94 env clones and their antigenicity profiles toward the three MAbs (2G12, 2F5, and IgG1b12) allowed us to evaluate the effects of natural amino acid substitutions on binding by these MAbs.

The 2G12 epitope is known to be dependent on N-linked glycans on gp120 (42, 48). Previous studies identified three major glycosylation sites for 2G12 binding (N295 in the C2 region, N332 in the C3 region, and N392 in the V4 loop) and two additional nonessential sites (N339 in the C3 domain and N386 in the V4 loop) (42, 44, 48). In our study, the three major sites (N295, N332, and N392) matched perfectly with the ability of MAb 2G12 to bind the envelope glycoproteins (Fig. 3). At least one of the major sites (N295, N332, or N392) was absent in every clone that did not bind 2G12. The eight early clones from patient 133 did not possess the glycosylation site at position 295, and the N392 attachment site was also absent in one of these early clones (Fig. 3A). The N332 site was replaced by another site two positions further downstream in seven of the eight early clones from patient 133 (Fig. 3A). The 15 early clones from patient 153 possessed neither the N332 site nor the N386 attachment site, whereas only the two clones that did not bind 2G12 among the 15 late clones lacked the N392 site (Fig. 3B). The eight early clones from patient 309 did not possess the N332 and N386 sites, and the single late clone that did not bind 2G12 had an N-to-S alteration at position 295 (Fig. 3D). Although six late clones bound 2G12, none of the clones from this patient possessed the N339 site, confirming that it is nonessential. The only two of the 15 early clones from patient 159 that did not bind 2G12 did not possess the glycan attachment sites at position 332 (19-3-7-4) or 392 (19-3-10-4). In this patient, the only two of the 12 late clones that weakly bound 2G12 (01-3-4-1 and 01-2-10-1) did not possess the N386 attachment site.

The linear 2F5 epitope was identified as linear within the sequence NEQELLELDKWASLWN, in which the ELDKWA motif is essential (30, 33, 38, 54). All the early and late clones from the four patients that possessed the ELDKWA motif bound 2F5 (Fig. 4). The five clones that presented a premature stop codon upstream or within the 2F5 epitope were not recognized by the 2F5 MAb. Clones 21-1-8-3 and 07-3-1-1 from patient 133 had a stop codon at positions 567 and 610, respectively. Clones 04-1-10-11 from patient 153, 159-3 from patient 159, and 06-3-15-5 from patient 309 had a premature stop codon at positions 563, 641, and 658, respectively. A major mutation, A667E, located within the ELDKWA motif, was associated with the failure of 2F5 to bind all the late clones of patient 133. The sporadic mutations (N656S and S671G) observed in env clones from patient 153 did not alter 2F5 binding (Fig. 4).

We tried to identify mutations or sequences that might be associated with the presence or absence of IgG1b12 binding by ELISA by comparing sequences in regions of gp120 implicated in recognition by this MAb. Unfortunately, we did not identify any sequences related to IgG1b12 binding properties. This is probably due to the complex conformation of the IgG1b12 epitope, the uncertainty of amino acids directly or indirectly involved in the interaction with the IgG1b12 paratope (32, 43, 53), and the high number of mutations, alterations, and insertions observed among the various clones of each patient.

DISCUSSION

Elucidation of the kinetics of exposure of neutralizing epitopes on the envelope of HIV-1 during the course of infection may explain how HIV can escape the immune system or why its envelope is such a poor immunogen due to its inability to induce broadly efficient neutralizing antibodies. We focused on three conserved neutralizing epitopes corresponding to the three human MAbs that have been best characterized to date and shown to be broadly neutralizing in vitro and protective in vivo. The main objective of our work was to document the exposure of these epitopes at the quasispecies level on the envelope glycoproteins derived from early viruses present at the time of acute infection, before any selective antibody pressure, and a few years later. This was done in four patients, three of whom were negative for HIV antibodies according to both screening ELISAs and Western blotting when the early sample was collected. The fourth patient was weakly positive according to ELISA with only a weak antibody activity toward gp160 according to Western blotting on the first sample. The antigenicity analysis was conducted on full-length recombinant envelope proteins produced by the Semliki Forest virus vector system, after cloning of at least 14 entire env genes amplified from proviral DNA for each sample. We focused on proviral DNA present in peripheral blood mononuclear cells instead of plasma RNA to obtain precise information about the evolution of the envelope, including archived proviruses in addition to the contemporary predominant variant(s). Although the clones from each patient at each period should represent the major quasispecies that have accumulated during the entire life of the virus in the host until the day of collection, we cannot claim that the sequences obtained are truly representative of those virus particles coevolving with the antibody response. A total of 141 clones were expressed; 94 underwent full antigenicity testing, and 47 were discarded because they were defective. The high rate of defective clones was not really surprising, because the env gene was amplified from proviral DNA. A similar rate of defective genes was found in another study that compared env genes derived from the brain and blood of patients with AIDS (31).

Our major finding was the constant lack of the 2G12 epitope in all the early envelope clones, associated with a switch toward its exposure on almost all late clones in three of the four patients. This significant off-on switch was qualitatively and quantitatively similar in these three patients. The situation was different in the fourth patient. The 2G12 epitope was already present in most of the early clones of this patient; the virus from this patient demonstrated less genetic drift 4 years later than did those from the other three patients. In contrast, we did not observe such changes for the IgG1b12 or 2F5 epitope. Both epitopes were exposed in early as well as late clones. The only exception was patient 133, whose virus did not expose or only weakly exposed these two epitopes. We found no significant difference between early and late envelope clones from the four patients for sCD4 binding.

We compared the sequences of all the clones to determine the molecular basis of the epitope detection. We placed particular emphasis on the 2G12 epitope due to its specific evolutionary dynamics, which were superimposable with the genetic drift. The most common phenomenon observed in the three patients with the clear off-on switch of the 2G12 epitope was a significant increase in the number of asparagine (N)-linked glycosylation sites between early and late clones. The median number of N-linked glycosylation sites was between 25 and 29 for early clones and was 31 for late clones. Rearrangements were also observed. Most of the changes occurred in the variable regions V1, V2, and V4 and, less often, V5 of gp120, but changes were also observed in the C2 and C3 constant regions. More precisely, we identified the N-glycosylation sites that are involved in the acquisition of the 2G12-positive phenotype. They corresponded perfectly to those previously identified by site-directed mutagenesis of the prototype strains HxB2 and JR-CSF (42, 44, 48). All the envelope clones that bound 2G12 possessed the three previously defined major N-linked glycosylation sites (N295, N332, and N392). The absence of any one of the three major sites, particularly frequent in the early clones of these three patients, resulted in a 2G12-negative phenotype. In the fourth patient, in whom most of the early clones were 2G12 positive, there was already a median of 31 potential N-linked glycosylation sites in the early quasispecies, which systematically included the three major sites described above. Interestingly, the two late clones from this patient that were least reactive to 2G12 did not possess the nonessential N386 attachment site. This confirms that this site is nonessential, or at least less important than the three major sites, for 2G12 binding. Similarly, clones from patient 309 that did not possess the N339 site were not reactive to 2G12, confirming that this site is nonessential for 2G12 binding. Therefore, our study confirms the recent theory of an evolving glycan shield at the surface of the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins (49) and provides new evidence that this acquisition or rearrangements of sugar moieties are associated with the appearance of the 2G12 epitope. However, our observations have been obtained in only four patients, three of them presenting the same viral envelope evolution. It is necessary to identify less laborious technical approaches in order to confirm the phenomenon in many more individuals, including patients infected with viruses from diverse clades. Furthermore, our study confirms that the N-linked glycosylation sites N295, N332, and N392 are essential for 2G12 binding in natural mutants, consistent with the data obtained by Scanlan et al. using a classical experimental approach based on site-directed mutagenesis (44).

Wei et al. postulated that the evolving glycan shield contributes to neutralization escape by preventing the binding of neutralizing antibodies but not receptor binding (49). Although we did not use functional assays, our ELISA data revealed no difference in the capacities of early and late envelope clones to bind sCD4. In other words, the increasing number of sugar moieties does not seem to inhibit access to CD4. However, it is possible that there is a maximum number of N-linked glycosylation sites beyond which the virus risks losing some functionality or fitness. It is thus noteworthy that the median number of N-linked glycosylation sites was 31 for the late clones of the three patients whose viral envelope glycoproteins evolved genetically and antigenically, whereas it was already 31 in the early clones of, and did not increase subsequently in, the patient whose envelope genes remained more stable over time.

Our study also revealed considerable heterogeneity between viral quasispecies in terms of exposure of the major neutralizing epitopes, IgG1b12, 2G12, and 2F5, in all of the HIV-1-infected individuals. This means that a natural infectious inoculum might contain free virions or infected cells that do not expose one or several of these epitopes and therefore might escape the corresponding neutralizing antibodies if preexisting in an exposed individual. This suggests that, if we consider that vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies or passively transferred neutralizing antibodies might prevent de novo infection, these antibodies should be directed toward at least several different conserved epitopes to avoid such escape. Finally, we consider that, based on the high and early frequency of envelope quasispecies that harbor the IgG1b12 and 2F5 epitopes, the hypothesis that the weak exposure of these major epitopes during the early months or years of infection can explain the rare and late induction of broadly neutralizing antibodies can probably be discarded. Thus, we still need to explain the poor immunogenicity of the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins in terms of induction of efficient broadly neutralizing antibodies to find ways to generate an efficient HIV vaccine candidate (9).

.

Acknowledgments

IgG1b12, 2G12, 2F5, sCD4, and MAb to CD4 were provided by D. P. Burton, P. Parren, H. Katinger, and ImmunoDiagnostics through the EU program EVA/MRC Centralised Facility for AIDS Reagents, NIBSC, United Kingdom (grant number QLK2-CT-1999-00609 and GP828102). We thank B. Giraudeau for his help and advice in the statistical analysis.

This study was supported by the Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le SIDA (ANRS, Paris, France). L. Dacheux was supported by a doctoral fellowship from the région Centre, France.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ataman-Onal, Y., C. Coiffier, A. Giraud, A. Babic-Erceg, F. Biron, and B. Verrier. 1999. Comparison of complete env gene sequences from individuals with symptomatic primary HIV type 1 infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 15:1035-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba, T. W., V. Liska, R. Hofmann-Lehmann, J. Vlasak, W. Xu, S. Ayehunie, L. A. Cavacini, M. R. Posner, H. Katinger, G. Stiegler, B. J. Bernacky, T. A. Rizvi, R. Schmidt, L. R. Hill, M. E. Keeling, Y. Lu, J. E. Wright, T. C. Chou, and R. M. Ruprecht. 2000. Human neutralizing monoclonal antibodies of the IgG1 subtype protect against mucosal simian-human immunodeficiency virus infection. Nat. Med. 6:200-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barin, F., S. Brunet, D. Brand, C. Moog, R. Peyre, F. Damond, P. Charneau, and F. Barré-Sinoussi. 2004. Interclade neutralization and enhancement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 identified by an assay using HeLa cells expressing both CD4 receptor and CXCR4/CCR5 coreceptors. J. Infect. Dis. 189:322-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binley, J. M., R. Wyatt, E. Desjardins, P. D. Kwong, W. Hendrickson, J. P. Moore, and J. Sodroski. 1998. Analysis of the interaction of antibodies with a conserved enzymatically deglycosylated core of the HIV type 1 envelope glycoprotein 120. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14:191-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brand, D., F. Lemiale, G. Thibault, B. Verrier, S. Lebigot, P. Roingeard, L. Buzelay, S. Brunet, and F. Barin. 2000. Antigenic properties of recombinant envelope glycoproteins derived from T-cell-line-adapted isolates or primary human immunodeficiency virus isolates and their relationship to immunogenicity. Virology 271:350-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton, D. R. 1997. A vaccine for HIV type 1: the antibody perspective. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:10018-10023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton, D. R., and D. C. Montefiori. 1997. The antibody response in HIV-1 infection. AIDS 11(Suppl. A):S87-S98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burton, D. R., J. Pyati, R. Koduri, S. J. Sharp, G. B. Thornton, P. W. Parren, L. S. Sawyer, R. M. Hendry, N. Dunlop, P. L. Nara, et al. 1994. Efficient neutralization of primary isolates of HIV-1 by a recombinant human monoclonal antibody. Science 266:1024-1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burton, D. R., R. C. Desrosiers, R. W. Doms, M. B. Feinberg, R. C. Gallo, B. Hahn, J. A. Hoxie, E. Hunter, B. Korber, A. Landay, M. M. Lederman, J. Lieberman, J. M. McCune, J. P. Moore, N. Nathanson, L. Picker, D. Richman, C. Rinaldo, M. Stevenson, D. I. Watkins, S. M. Wolinsky, and J. A. Zack. 2004. A sound rationale needed for phase III HIV-1 vaccine trials. Science 303:316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calarese, D. A., C. N. Scanlan, M. B. Zwick, S. Deechongkit, Y. Mimura, R. Kunert, P. Zhu, M. R. Wormald, R. L. Stanfield, K. H. Roux, J. W. Kelly, P. M. Rudd, R. A. Dwek, H. Katinger, D. R. Burton, and I. A. Wilson. 2003. Antibody domain exchange is an immunological solution to carbohydrate cluster recognition. Science 300:2065-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao, Y., L. Qin, L. Zhang, J. Safrit, and D. D. Ho. 1995. Virologic and immunologic characterization of long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:201-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conley, A. J., J. A. Kessler II, L. J. Boots, J. S. Tung, B. A. Arnold, P. M. Keller, A. R. Shaw, and E. A. Emini. 1994. Neutralization of divergent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants and primary isolates by IAM-41-2F5, an anti-gp41 human monoclonal antibody. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:3348-3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Souza, M. P., D. Livnat, J. A. Bradac, S. H. Bridges, et al. 1997. Evaluation of monoclonal antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolates by neutralization assays: performance criteria for selecting candidate antibodies for clinical trials. J. Infect. Dis. 175:1056-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fouts, T. R., J. M. Binley, A. Trkola, J. E. Robinson, and J. P. Moore. 1997. Neutralization of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolate JR-FL by human monoclonal antibodies correlates with antibody binding to the oligomeric form of the envelope glycoprotein complex. J. Virol. 71:2779-2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gauduin, M. C., P. W. Parren, R. Weir, C. F. Barbas, D. R. Burton, and R. A. Koup. 1997. Passive immunization with a human monoclonal antibody protects hu-PBL-SCID mice against challenge by primary isolates of HIV-1. Nat. Med. 3:1389-1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall, T. A. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41:95-98. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofmann-Lehmann, R., R. A. Rasmussen, J. Vlasak, B. A. Smith, T. W. Baba, V. Liska, D. C. Montefiori, H. M. McClure, D. C. Anderson, B. J. Bernacky, T. A. Rizvi, R. Schmidt, L. R. Hill, M. E. Keeling, H. Katinger, G. Stiegler, M. R. Posner, L. A. Cavacini, T. C. Chou, and R. M. Ruprecht. 2001. Passive immunization against oral AIDS virus transmission: an approach to prevent mother-to-infant HIV-1 transmission? J. Med. Primatol. 30:190-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korber, B., B. T. Foley, C. Kuiken, S. K. Pillai, and J. G. Sodroski. 1998. Numbering positions in HIV relative to HXB2CG, p. III-102-III-111. In B. Korber, C. L. Kuiken, B. Foley, F. Hahn, F. McCutchan, J. W. Mellors, and J. Sodroski (ed.), Human retroviruses and AIDS 1998. Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, N. Mex.

- 19.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, I. B. Jakobsen, and M. Nei. 2001. MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Bioinformatics 17:1244-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunert, R., F. Ruker, and H. Katinger. 1998. Molecular characterization of five neutralizing anti-HIV type 1 antibodies: identification of nonconventional D segments in the human monoclonal antibodies 2G12 and 2F5. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14:1115-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwong, P. D., R. Wyatt, S. Majeed, J. Robinson, R. W. Sweet, J. Sodroski, and W. A. Hendrickson. 2000. Structures of HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoproteins from laboratory-adapted and primary isolates. Structure Fold Des. 8:1329-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwong, P. D., R. Wyatt, J. Robinson, R. W. Sweet, J. Sodroski, and W. A. Hendrickson. 1998. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature 393:648-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mascola, J. R., M. G. Lewis, G. Stiegler, D. Harris, T. C. VanCott, D. Hayes, M. K. Louder, C. R. Brown, C. V. Sapan, S. S. Frankel, Y. Lu, M. L. Robb, H. Katinger, and D. L. Birx. 1999. Protection of macaques against pathogenic simian/human immunodeficiency virus 89.6PD by passive transfer of neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 73:4009-4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mascola, J. R., G. Stiegler, T. C. VanCott, H. Katinger, C. B. Carpenter, C. E. Hanson, H. Beary, D. Hayes, S. S. Frankel, D. L. Birx, and M. G. Lewis. 2000. Protection of macaques against vaginal transmission of a pathogenic HIV-1/SIV chimeric virus by passive infusion of neutralizing antibodies. Nat. Med. 6:207-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mo, H., L. Stamatatos, J. E. Ip, C. F. Barbas, P. W. Parren, D. R. Burton, J. P. Moore, and D. D. Ho. 1997. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutants that escape neutralization by human monoclonal antibody IgG1b12. J. Virol. 71:6869-6874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moog, C., H. J. Fleury, I. Pellegrin, A. Kirn, and A. M. Aubertin. 1997. Autologous and heterologous neutralizing antibody responses following initial seroconversion in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals. J. Virol. 71:3734-3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore, J. P., Y. Cao, D. D. Ho, and R. A. Koup. 1994. Development of the anti-gp120 antibody response during seroconversion to human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 68:5142-5155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore, J. P., F. E. McCutchan, S. W. Poon, J. Mascola, J. Liu, Y. Cao, and D. D. Ho. 1994. Exploration of antigenic variation in gp120 from clades A through F of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by using monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol. 68:8350-8364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moulard, M., S. K. Phogat, Y. Shu, A. F. Labrijn, X. Xiao, J. M. Binley, M. Y. Zhang, I. A. Sidorov, C. C. Broder, J. Robinson, P. W. Parren, D. R. Burton, and D. S. Dimitrov. 2002. Broadly cross-reactive HIV-1-neutralizing human monoclonal Fab selected for binding to gp120-CD4-CCR5 complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:6913-6918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muster, T., F. Steindl, M. Purtscher, A. Trkola, A. Klima, G. Himmler, F. Ruker, and H. Katinger. 1993. A conserved neutralizing epitope on gp41 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 67:6642-6647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohagen, A., A. Devitt, K. J. Kunstman, P. R. Gorry, P. P. Rose, B. Korber, J. Taylor, R. Levy, R. L. Murphy, S. M. Wolinsky, and D. Gabuzda. 2003. Genetic and functional analysis of full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env genes derived from brain and blood of patients with AIDS. J. Virol. 77:12336-12345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pantophlet, R., E. Ollmann Saphire, P. Poignard, P. W. Parren, I. A. Wilson, and D. R. Burton. 2003. Fine mapping of the interaction of neutralizing and nonneutralizing monoclonal antibodies with the CD4 binding site of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120. J. Virol. 77:642-658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker, C. E., L. J. Deterding, C. Hager-Braun, J. M. Binley, N. Schulke, H. Katinger, J. P. Moore, and K. B. Tomer. 2001. Fine definition of the epitope on the gp41 glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 for the neutralizing monoclonal antibody 2F5. J. Virol. 75:10906-10911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parren, P. W., H. J. Ditzel, R. J. Gulizia, J. M. Binley, C. F. Barbas III, D. R. Burton, and D. E. Mosier. 1995. Protection against HIV-1 infection in hu-PBL-SCID mice by passive immunization with a neutralizing human monoclonal antibody against the gp120 CD4-binding site. AIDS 9:F1-F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parren, P. W., P. A. Marx, A. J. Hessell, A. Luckay, J. Harouse, C. Cheng-Mayer, J. P. Moore, and D. R. Burton. 2001. Antibody protects macaques against vaginal challenge with a pathogenic R5 simian/human immunodeficiency virus at serum levels giving complete neutralization in vitro. J. Virol. 75:8340-8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parren, P. W., J. P. Moore, D. R. Burton, and Q. J. Sattentau. 1999. The neutralizing antibody response to HIV-1: viral evasion and escape from humoral immunity. AIDS 13(Suppl. A):S137-S162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poignard, P., R. Sabbe, G. R. Picchio, M. Wang, R. J. Gulizia, H. Katinger, P. W. Parren, D. E. Mosier, and D. R. Burton. 1999. Neutralizing antibodies have limited effects on the control of established HIV-1 infection in vivo. Immunity 10:431-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Purtscher, M., A. Trkola, A. Grassauer, P. M. Schulz, A. Klima, S. Dopper, G. Gruber, A. Buchacher, T. Muster, and H. Katinger. 1996. Restricted antigenic variability of the epitope recognized by the neutralizing gp41 antibody 2F5. AIDS 10:587-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richman, D. D., T. Wrin, S. J. Little, and C. J. Petropoulos. 2003. Rapid evolution of the neutralizing antibody response to HIV type 1 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:4144-4149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roben, P., J. P. Moore, M. Thali, J. Sodroski, C. F. Barbas III, and D. R. Burton. 1994. Recognition properties of a panel of human recombinant Fab fragments to the CD4 binding site of gp120 that show differing abilities to neutralize human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 68:4821-4828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanders, R. W., M. Venturi, L. Schiffner, R. Kalyanaraman, H. Katinger, K. O. Lloyd, P. D. Kwong, and J. P. Moore. 2002. The mannose-dependent epitope for neutralizing antibody 2G12 on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein gp120. J. Virol. 76:7293-7305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saphire, E. O., P. W. Parren, R. Pantophlet, M. B. Zwick, G. M. Morris, P. M. Rudd, R. A. Dwek, R. L. Stanfield, D. R. Burton, and I. A. Wilson. 2001. Crystal structure of a neutralizing human IgG against HIV-1: a template for vaccine design. Science 293:1155-1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scanlan, C. N., R. Pantophlet, M. R. Wormald, E. Ollmann Saphire, R. Stanfield, I. A. Wilson, H. Katinger, R. A. Dwek, P. M. Rudd, and D. R. Burton. 2002. The broadly neutralizing anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody 2G12 recognizes a cluster of α1→2 mannose residues on the outer face of gp120. J. Virol. 76:7306-7321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stiegler, G., R. Kunert, M. Purtscher, S. Wolbank, R. Voglauer, F. Steindl, and H. Katinger. 2001. A potent cross-clade neutralizing human monoclonal antibody against a novel epitope on gp41 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:1757-1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trkola, A., A. B. Pomales, H. Yuan, B. Korber, P. J. Maddon, G. P. Allaway, H. Katinger, C. F. Barbas III, D. R. Burton, D. D. Ho, and J. P. Moore. 1995. Cross-clade neutralization of primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by human monoclonal antibodies and tetrameric CD4-IgG. J. Virol. 69:6609-6617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trkola, A., M. Purtscher, T. Muster, C. Ballaun, A. Buchacher, N. Sullivan, K. Srinivasan, J. Sodroski, J. P. Moore, and H. Katinger. 1996. Human monoclonal antibody 2G12 defines a distinctive neutralization epitope on the gp120 glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 70:1100-1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wei, X., J. M. Decker, S. Wang, H. Hui, J. C. Kappes, X. Wu, J. F. Salazar-Gonzalez, M. G. Salazar, J. M. Kilby, M. S. Saag, N. L. Komarova, M. A. Nowak, B. H. Hahn, P. D. Kwong, and G. M. Shaw. 2003. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature 422:307-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wyatt, R., P. D. Kwong, E. Desjardins, R. W. Sweet, J. Robinson, W. A. Hendrickson, and J. G. Sodroski. 1998. The antigenic structure of the HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Nature 393:705-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wyatt, R., and J. Sodroski. 1998. The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens, and immunogens. Science 280:1884-1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang, Y. J., C. Fracasso, J. R. Fiore, A. Bjorndal, G. Angarano, A. Gringeri, and E. M. Fenyo. 1997. Augmented serum neutralizing activity against pri-mary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) isolates in two groups of HIV-1 infected long-term nonprogressors. J. Infect. Dis. 176:1180-1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zwick, M. B., R. Kelleher, R. Jensen, A. F. Labrijn, M. Wang, G. V. Quinnan, Jr., P. W. Parren, and D. R. Burton. 2003. A novel human antibody against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 is V1, V2, and V3 loop dependent and helps delimit the epitope of the broadly neutralizing antibody immunoglobulin G1 b12. J. Virol. 77:6965-6978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zwick, M. B., A. F. Labrijn, M. Wang, C. Spenlehauer, E. O. Saphire, J. M. Binley, J. P. Moore, G. Stiegler, H. Katinger, D. R. Burton, and P. W. Parren. 2001. Broadly neutralizing antibodies targeted to the membrane-proximal external region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein gp41. J. Virol. 75:10892-10905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]