Abstract

Extremophilic archaea were stained with the LIVE/DEAD BacLight kit under conditions of high ionic strength and over a pH range of 2.0 to 9.3. The reliability of the kit was tested with haloarchaea following permeabilization of the cells. Microorganisms in hypersaline environmental samples were detectable with the kit, which suggests its potential application to future extraterrestrial halites.

Numerous archaea (archaebacteria) thrive in hostile conditions such as salt brines, hot springs, and acidic or alkaline environments (20). Their membrane lipids differ from those of (eu)bacteria and other organisms because they contain ether linkages instead of ester linkages, are composed of regularly branched phytanyl and biphytanyl chains instead of fatty acyl chains, and possess glycerol ethers, which are sn-2,3 substituted rather than sn-1,2 substituted (13). These properties are thought to contribute to the greater chemical stability of archaeal lipids (13, 22) and the generally low permeability of archaeal membranes (5, 14). The LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit (henceforth referred to as the LIVE/DEAD kit) from Molecular Probes is widely used for the enumeration of bacteria (2, 8, 12) and provides an indication of the fraction of active cells. The kit consists of two nucleic acid stains: SYTO 9, which penetrates most membranes freely, and propidium iodide, which is highly charged and normally does not permeate cells but does penetrate damaged membranes. Simultaneous application of both dyes therefore results in green fluorescence of viable cells with an intact membrane, whereas dead cells, because of a compromised membrane, show intense red fluorescence (10). Archaea have not been treated with the LIVE/DEAD kit, except for one psychrophilic isolate (15); in view of the low permeability of their membranes and their existence in habitats that often border on the physicochemical limits of life, it was of interest to determine if the LIVE/DEAD kit would detect extremophilic archaea and provide reliable information about their viability.

Archaeal strains were purchased from the DSMZ (Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen, Braunschweig, Germany), except Halobacterium sp. strain NRC-1 ATCC 700922, which was obtained from LGC, London, United Kingdom. Haloarchaea were grown at 37°C in M2 medium (27), except Halococcus and haloalkaliphiles, which were grown in M2S medium (25) or Tindall's medium (26), respectively, and Halobacterium sp. strain NRC-1, which was grown in ATCC medium no. 2185 (http://www.lgcpromochem.com/atcc/). Acidianus brierleyi DSM 1651T (21) and Sulfolobus acidocaldarius DSM 639T (31) were grown at 65 to 70°C in DSM medium no. 150 (http://www.dsmz.de/media/med150.htm) and ATCC medium no. 1723 (http://www.atcc.org/SearchCatalogs/Search.cfm), respectively. The dyes of LIVE/DEAD BacLight kit L-7012 (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, Oreg.) were freshly diluted with water and used as previously described (3, 10). Staining with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was done as described by Antón et al. (1) for noncoccoid haloarchaea or by Porter and Feig (18) for halococci, except that cells were fixed and permeabilized by brief treatment with 60% ethanol. Samples were viewed in an Axioskop microscope (Zeiss) or a Laser confocal scanning microscope (Zeiss KLM 510).

Staining at extremes of pH and at high ionic strength.

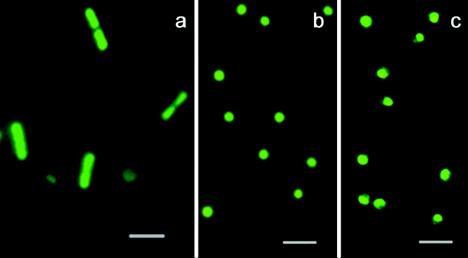

Figure 1 shows staining of archaea at pH extremes. S. acidocaldarius cells (Fig. 1b and c) were grown and stained at pHs 5.9 and 2.0, respectively, and Natronomonas pharaonis cells (Fig. 1a) were grown and stained at pH 9.3; similar staining (not shown) was observed at pH 9.3 with Natronococcus occultus and at pH 2.0 with A. brierleyi, which is related to Sulfolobus (11). Since the Natronomonas and Natronococcus species had been grown in the presence of 4 M NaCl, the results suggested also that high ionic strength did not interfere with staining. This observation was corroborated with several haloneutrophilic archaea (Halobacterium sp. strain NRC-1, Halorubrum saccharovorum, Haloferax volcanii, Halococcus morrhuae), which were grown in media containing 4.0 to 4.28 M NaCl. Most haloarchaea contain in their cytoplasm high concentrations of salt, which range from 3.7 to 5.3 M KCl and 0.8 to 1.63 M NaCl (16). The LIVE/DEAD kit has been used so far in circumneutral media and solutions of low or only moderate ionic strength; the data provided here suggest its usefulness over a wide range of pHs and at high ionic strength at neutral or alkaline pH. It may be concluded that SYTO 9 penetrated cells well at alkaline pH, although its maximum fluorescence is to be expected at acidic pH (2). In summary, the dyes of the LIVE/DEAD kit permeated archaeal bilayer membranes, which contain C20C20 or, in the case of haloalkaliphiles, additional C20C25 diethers (9), as well as monolayer membranes from thermoacidophiles, which contain C40C40 tetraethers (13) and are notoriously low in permeability (5, 14, 29).

FIG. 1.

Staining of extremophilic archaea with the LIVE/DEAD kit. Panels: a, N. pharaonis; b and c, S. acidocaldarius grown and stained at pH 5.9 (b) or 2.0 (c). Bars, 2 μm.

Assessing the reliability of the LIVE/DEAD kit for archaea.

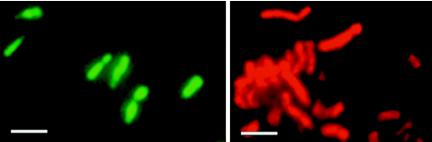

Haloarchaeal species, except halococci, are lysed and killed by placement in distilled water (9). This property was used for an evaluation of the reliability of the LIVE/DEAD kit. Unambiguous results were obtained with Halobacterium sp. strain NRC-1, which exhibited red fluorescence following incubation in water for 5 min (Fig. 2); no CFU were detected on agar plates, which were incubated for up to 4 weeks. Longer exposure to water (>5 min) caused complete disintegration of the cells, with the appearance of string-like structures and debris (not shown). Halococci were lysed only to a small extent when they were placed in water for up to 60 min, since 85 to 88% (of 750 counted cells) of H. dombrowskii H4 cells retained their green fluorescence and were still culturable (not shown). The results suggested that the membranes of noncoccoid haloarchaea became permeable within minutes upon exposure to water and that the resulting nonviability was readily apparent by the changing fluorescence of cells stained with the LIVE/DEAD kit, in contrast to halococci, which were rather resistant to the action of water. Halococci (H. dombrowskii H4, H. morrhuae, and H. salifodinae BIp) were permeabilized by treatment with 60% ethanol and stained with DAPI (18) afterwards, which preserved well their morphological features; subsequent staining with the LIVE/DEAD kit produced only red fluorescence and no culturable cells, indicating loss of membrane intactness. The LIVE/DEAD kit thus allowed rapid evaluation of the integrity of haloarchaeal membranes and the viability of cells following exposure to lethal treatments.

FIG. 2.

Effect of low-salt stress on halobacteria. Cells of Halobacterium sp. strain NRC-1 were kept in the presence of 4 M NaCl (left) or exposed to distilled water for 5 min prior to staining with the LIVE/DEAD kit (right). Bars, 2 μm.

Intermediate colors.

Ambiguous colors like yellow or orange have sometimes been observed in bacterial cells stained with the LIVE/DEAD kit (2). In our experiments, only coccoid haloarchaea, which generally grow in clusters and aggregates, showed occasionally intermediate yellowish colors; singly growing cells of noncoccoid haloarchaea and thermoacidophiles showed unambiguous (either red or green) fluorescence.

Effects of stains on culturability of haloarchaea.

The possibility of inhibition of haloarchaeal growth by the kit's components and DAPI was examined. Cells of Halobacterium sp. strain NRC-1 and H. dombrowskii H4, both at an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0, were incubated with the LIVE/DEAD kit at the same concentrations as used for staining (0.01 mM SYTO 9, 0.03 mM propidium iodide). The CFU counts of Halobacterium sp. strain NRC-1 on five to seven agar plates per experiment were 6.3 × 108 CFU/ml ± 6.4% (coefficient of variation) after 15 min of incubation and 2.8 × 108 CFU/ml ± 9.0% after 24 h of incubation with the LIVE/DEAD kit. Cells of H. dombrowskii H4 showed more than 98% viable cells following incubation with dyes for 24 h (total of 350 counted cells). These results indicate that incubation with the LIVE/DEAD kit for up to 24 h did not markedly reduce the viability of these two haloarchaeal species. In contrast, DAPI is known to inhibit the growth of Halobacterium sp. strain GRB at concentrations of a few micrograms per milliliter (7) and that of Sulfolobus (17). We found that an even lower concentration (0.014 μM) inhibited the growth of H. salifodinae BIp when cells had been exposed for 2 h to DAPI.

Environmental hypersaline samples.

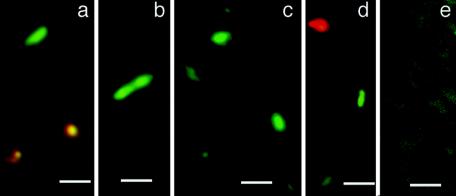

We have previously isolated several novel haloarchaeal species from rock salt, which is believed to have been deposited about 280 million years ago (4, 23, 25) and which contains numerous as yet uncultured strains (19). We attempted to visualize directly the presence of halophilic microorganisms in dissolved rock salt and in samples from natural hypersaline brines. Figure 3 shows several particles about 1 to 2 μm long with green fluorescence in a sample of Dead Sea water (Fig. 3a and b) that had been stored at 4°C for about 3 years and in dissolved rock salt (Fig. 3c and d) from the salt mine in Altaussee, Austria, following staining with the LIVE/DEAD kit. According to their sizes and shapes, they could represent viable halophilic prokaryotes. Autofluorescent particles were not observed. Occasionally, hazy-appearing material was detected in dissolved rock salt, which produced weak red or green fluorescence (Fig. 3, e). In the Dead Sea water, rod-shaped particles of green fluorescence, including an apparently dividing cell (Fig. 3b), were present; some particles showed a transient yellow fluorescence (Fig. 3a). CFU densities in this sample were between 180 and 240/ml on agar plates containing M2S medium, thus corroborating the presence of viable halophilic microorganisms. CFU densities from dissolved rock salt varied between 10 and 130 ± 20/ml (see also reference 24). A direct correlation between fluorescent particles and CFU was obtained with a confocal scanning laser microscope, which affords precise volumes of fields of view; manual counting of fluorescent cells of pure cultures of Halobacterium sp. strain NRC-1, which contained 3.6 × 1010 CFU/ml ± 11%, according to streak plates (n = 12), yielded 3.9 × 1010 cells/ml ± 9% (n = 4). Older cultures, which contained about 20% dead cells, as estimated from red fluorescence, produced correspondingly lower values (7.8 × 109 CFU/ml ± 10%; n = 4). Although these data were from a rather limited number of experiments, it could be inferred that no serious underestimation of the CFU densities of viable haloarchaea had occurred.

FIG. 3.

Fluorescent particles in environmental samples. Dead Sea water (a, b) and dissolved rock salt (c, d, e) from the Permian deposit at Altaussee, Austria, were treated with the LIVE/DEAD kit without any prior preparation; e, hazy staining of material in dissolved rock salt. Bars, 2 μm.

Extraterrestrial halite.

The search for life in the solar system and beyond is a goal of several space agencies in the 21st century (6). Extraterrestrial materials might be return samples or well-characterized meteorites; some of these are known to contain halite (28, 30, 32). Fluorescent dyes, such as those in the LIVE/DEAD kit, may be suitable agents for life detection experiments because of their high sensitivity and robustness in extreme environments. In contrast to DAPI, the LIVE/DEAD kit reagents were tolerated well by haloarchaea, and poststaining cultivation of detected particles should in principle be possible. If microbial forms of life with membranes and nucleic acids similar to those found on earth exist in extraterrestrial materials, the LIVE/DEAD kit dyes are promising for use in their detection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by FWF projects P13995-MOB and P16260-B07.

We thank Claudia Gruber and Michaela Klappacher, both at the University of Salzburg, for expert technical help and Michael Mayr, Salinen, Austria, and Christa Schaubmaier, State Hospital of Linz, Linz, Austria, for samples of rock salt and Dead Sea water, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antón, J., E. Llobet-Brossa, F. Rodríguez-Valera, and R. Amann. 1999. Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of the prokaryotic community inhabiting crystallizer ponds. Environ. Microbiol. 1:517-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulos, L., M. Prevost, B. Barbeau, J. Coallier, and R. Desjardins. 1999. LIVE/DEAD BacLight: application of a new rapid staining method for direct enumeration of viable and total bacteria in drinking water. J. Microbiol. Methods 37:77-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bunthof, C. J., S. van Schalkwijk, W. Meijer, T. Abee, and J. Hugenholtz. 2001. Fluorescent method for monitoring cheese starter permeabilization and lysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 6:4264-4271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denner, E. B. M., T. J. McGenity, H.-J. Busse, G. Wanner, W. D. Grant, and H. Stan-Lotter. 1994. Halococcus salifodinae sp. nov., an archaeal isolate from an Austrian salt mine. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44:774-780. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elferink, M. G., J. G. de Wit, A. J. Driessen, and W. N. Konings. 1994. Stability and proton-permeability of liposomes composed of archaeal tetraether lipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1193:247-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foing, B. 2002. Space activities in exo/astrobiology, p. 389-398. In G. Horneck and C. Baumstark-Khan (ed.), Astrobiology. The quest for the conditions of life. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 7.Gadelle, D., and P. Forterre. 1994. DNA intercalating drugs inhibit positive supercoiling induced by novobiocin in halophilic archaea. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 123:161-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gasol, J. M., U. L. Zweifel, F. Peters, J. A. Fuhrman, and A. Hagstrom. 1999. Significance of size and nucleic acid content heterogeneity as measured by flow cytometry in natural planktonic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4475-4483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant, W. D., M. Kamekura, T. J. McGenity, and A. Ventosa. 2001. Class III. Halobacteria class. nov., p. 294-301. In D. R. Boone, R. W. Castenholz, and G. M. Garrity (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, second ed., vol. I, Springer Verlag, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haugland, R. P. 2002. LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kits, p. 626-628. In J. Gregory (ed.), Handbook of fluorescent probes and research products, ninth edition. Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.

- 11.Huber, H., and K. O. Stetter. 2001. Order III. Sulfolobales Stetter 1989d, 496VP, p. 198-204. In D. R. Boone, R. W. Castenholz, and G. M. Garrity (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, second ed., vol. I, Springer Verlag, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janssen, P. H., P. S. Yates, B. E. Grinton, P. M. Taylor, and M. Sait. 2002. Improved culturability of soil bacteria and isolation in pure culture of novel members of the divisions Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:2391-2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kates, M. 1993. Membrane lipids of archaea, p. 261-295. In The biochemistry of the archaea. M. Kates, D. J. Kushner, and A. T. Matheson (ed.). Elsevier Science Publishers, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 14.Mathai, J. C., G. D. Sprott, and M. L. Zeidel. 2001. Molecular mechanisms of water and solute transport across archaebacterial lipid membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 276:27266-27271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moissl, C., C. Rudolph, R. Rachel, M. Koch, and R. Huber. 2003. In situ growth of the novel SM1 euryarchaeon from a string-of-pearls-like microbial community in its cold biotope, its physical separation and insights into its structure and physiology. Arch. Microbiol. 180:211-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oren, A. 2002. Intracellular salt concentrations and ion metabolism in halophilic microorganisms, p. 207-231. In A. Oren (ed.), Halophilic microorganisms and their environments. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 17.Poplawski, A., and R. Bernander. 1997. Nucleoid structure and distribution in thermophilic archaea. J. Bacteriol. 179:7625-7630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porter, K. G., and Y. S. Feig. 1980. The use of DAPI for identifying and counting aquatic microflora. Limnol. Oceanogr. 25:943-948. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radax, C., C. Gruber, and H. Stan-Lotter. 2001. Novel haloarchaeal 16S rRNA gene sequences from Alpine Permo-Triassic rock salt. Extremophiles 5:221-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothschild, L. J., and R. L. Mancinelli. 2001. Life in extreme environments. Nature 409:1092-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segerer, A., A. Neuner, J. K. Kristjansson, and K. O. Stetter. 1986. Acidianus infernus gen. nov., sp. nov., and Acidianus brierleyi comb. nov.: facultatively aerobic, extremely acidophilic thermophilic sulfur-metabolizing archaebacteria. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 36:559-564. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sprott, G. D. 1992. Structures of archaebacterial membrane lipids. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 24:555-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stan-Lotter, H., T. J. McGenity, A. Legat, E. B. M. Denner, K. Glaser, K. O. Stetter, and G. Wanner. 1999. Very similar strains of Halococcus salifodinae are found in geographically separated Permo-Triassic salt deposits. Microbiology 145:3565-3574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stan-Lotter, H., C. Radax, C. Gruber, T. J. McGenity, A. Legat, G. Wanner, and E. B. M. Denner. 2000. The distribution of viable microorganisms in Permo-Triassic rock salt, p. 921-926. In SALT 2000. R. M. Geertman (ed.), 8th World Salt Symposium, vol. 2. Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stan-Lotter, H., M. Pfaffenhuemer, A. Legat, H.-J. Busse, C. Radax, and C. Gruber. 2002. Halococcus dombrowskii sp. nov., an archaeal isolate from a Permo-Triassic alpine salt deposit. Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 52:1807-1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tindall, B. J., A. A. Mills, and W. D. Grant. 1980. An alkalophilic red halophilic bacterium with a low magnesium requirement from a Kenyan soda lake. J. Gen. Microbiol. 116:257-260. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomlinson, G. A., and L. I. Hochstein. 1976. Halobacterium saccharovorum sp. nov., a carbohydrate-metabolizing, extremely halophilic bacterium. Can. J. Microbiol. 22:587-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Treiman, A. H., J. D. Gleason, and D. D. Bogard. 2000. The SNC meteorites are from Mars. Planet. Space Sci. 48:1213-1230. [Google Scholar]

- 29.van de Vossenberg, J. L. C. M., A. J. M. Driessen, and W. N. Konings. 1998. The essence of being extremophilic: the role of the unique archaeal membrane lipids. Extremophiles 2:163-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whitby, J., R. Burgess, G. Turner, J. Gilmour, and J. Bridges. 2000. Extinct 129I halite from a primitive meteorite: evidence for evaporite formation in the early solar system. Science 288:1819-1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zillig, W., K. O. Stetter, S. Wunderl, W. Schulz, H. Priess, and I. Scholz. 1980. The Sulfolobus-“Caldariella” group: taxonomy on the basis of the structure of DNA-dependent RNA polymerases. Arch. Microbiol. 125:259-269. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zolensky, M. E., R. J. Bodnar, E. K. Gibson, L. E. Nyquist, Y. Reese, C. Y. Shih, and H. Wiesman. 1999. Asteroidal water within fluid inclusion-bearing halite in an H5 chondrite, Monahans (1998). Science 285:1377-1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]