Abstract

Background and purpose — It is unclear whether metal particles and ions produced by mechanical wear and corrosion of hip prostheses with metal-on-metal (MoM) bearings have systemic adverse effects on health. We compared the risk of heart failure in patients with conventional MoM total hip arthroplasty (THA) and in those with metal-on-polyethylene (MoP) THA.

Patients and methods — We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs health claims database on patients who received conventional THA for osteoarthritis between 2004 and 2012. The MoM THAs were classified into groups: Articular Surface Replacement (ASR) XL Acetabular System, other large-head (LH) (> 32 mm) MoM, and small-head (SH) (≤ 32 mm) MoM. The primary outcome was hospitalization for heart failure after THA.

Results — 4,019 patients with no history of heart failure were included (56% women). Men with an ASR XL THA had a higher rate of hospitalization for heart failure than men with MoP THA (hazard ratio (HR) = 3.2, 95% CI: 1.6–6.5). No statistically significant difference in the rate of heart failure was found with the other LH MoM or SH MoM compared to MoP in men. There was no statistically significant difference in heart failure rate between exposure groups in women.

Interpretation — An association between ASR XL and hospitalization for heart failure was found in men. While causality between ASR XL and heart failure could not be established in this study, it highlights an urgent need for further studies to investigate the possibility of systemic effects associated with MoM THA.

It has been reported that more than 1 million metal-on-metal (MoM) bearing total hip arthroplasties (THAs) have been performed globally (Kwon et al. 2014). While MoM hips were generally recommended by companies for young and active patients, these devices became popular among orthopedic surgeons and were used in a wide range of patients. The advantage of the MoM hip design, which permitted the use of a large femoral head, was a lower risk of dislocation and an improved range of movement compared to other bearings.

MoM hip prostheses with components made of cobalt-chromium alloys are known to produce high levels of metal particles and metal ions from wear and corrosion (Lavigne et al. 2011, Chang et al. 2013, Jantzen et al. 2013). Resultant damage to local soft tissues and periprosthetic bone and (consequently) increased rates of revision surgery have often been reported (Pandit et al. 2008, Langton et al. 2010, Fary et al. 2011, Sampson and Hart 2012, Hug et al. 2013, Langton et al. 2013). The revision rates vary according to the class of MoM prosthesis (Graves et al. 2011). For example, conventional stemmed large-head (LH) MoM (> 32 mm diameter) prostheses have the highest rate of revision compared to both small-head (SH) MoM (≤ 32 mm diameter) and resurfacing hip replacement (AOANJRR 2015).

The risk of revision has also varied within class. The Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR) has reported that the cumulative percentage of revisions at 7 years for the 13 most commonly used conventional LH MoM ranges from 4.3% to 37% (AOANJRR SR 2015). The one with the highest proportion of revisions was the Articular Surface Replacement (ASR) XL Acetabular System (DePuy). This device was withdrawn from the market in Australia in 2009, and was subject to a worldwide recall in 2010. The high rate of revision for this prosthesis is due mainly to metal ion-related pathology, and this is almost certainly related to design and manufacturing differences compared to other LH MoM prostheses.

In addition to the local effects reported, there has been increasing concern that the dissemination of wear particles and increased blood levels of metal ions, especially cobalt, may be associated with systemic adverse effects on health (Campbell and Estey 2013). There is no doubt that high levels of serum cobalt are associated with systemic adverse effects. This has been known since the 1960s when there was an epidemic of heart failure in people who drank beer containing cobalt, which was added as a foam stabilizer (Morin and Daniel 1967).

To date, there have been a number of case reports of suspected systemic adverse effects on health following the use of MoM THA (Cheung et al. 2016, Zywiel et al. 2016). In a case study of a patient with bilateral ASR XL prostheses who developed heart failure in both native heart and transplanted heart, Allen et al. (2014) found signs of mitochondrial injury and elevated cobalt levels in heart tissue, supporting the diagnosis of cobalt-induced cardiomyopathy. There have also been case reports of neuropathies (auditory, optic, polyneuropathy), depression, cognitive impairment, hypothyroidism, and renal function impairment associated with MoM bearings (Tower 2010, Mao et al. 2011, Cohen 2012, Machado et al. 2012, Devlin et al. 2013, Gessner et al. 2015). Furthermore, a cross-sectional study of patients with resurfacing MoM hip arthroplasties identified reduced cardiac ejection fraction in asymptomatic patients who had cobalt levels above the cobalt levels in patients in a matched reference group, but below what was previously thought to be the threshold concentration for prosthesis malfunction (Prentice et al. 2013).

Although current evidence suggests that MoM THA may be associated with detrimental systemic health effects, the incidence of this remains unknown. The aim of this study was to determine whether conventional MoM THA is associated with a higher rate of developing heart failure compared to a reference cohort who received THA with the commonly used bearing of metal-on-polyethylene (MoP). An additional aim was to determine whether MoM THA was associated with higher mortality than in the reference cohort.

Methods

Study sample

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) health claims database. The database contains comprehensive data on prescription medicines, hospital admissions in both public and private hospitals, procedures, and medical devices for all Australian veterans and their spouses. The database has a current treatment population of 233,800 veterans with a median age of 82 years. Veterans, widowers/widows, or dependents of veterans were included if they had full entitlement to all DVA services. The DVA provides funding for all treatments related to all medical conditions in these patients.

The study sample consisted of patients who underwent primary THA for treatment of osteoarthritis in private hospitals between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2012. Primary THA procedures were identified using the Australian Classification of Health Interventions (ACHI/ICD-10-AM) procedure codes 49318-00 and 49319-00. For those patients who underwent more than 1 primary hip procedure during the study period, only the initial primary THA undertaken in the study period was used in the analysis.

Patients who had a record of hospitalization for heart failure (either primary or any secondary discharge diagnoses, ICD-10-AM codes I50.0–I50.9) in the year prior to the THA were excluded (n = 273). In addition, those who were dispensed heart failure medication in the year before were also excluded (n = 762) (Table 1). Specification of heart failure medication was based on the National Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand guidelines for management of chronic heart failure (2011) and included angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor with a loop diuretic, heart-specific beta blocker, spironolactone, or loop diuretics with an angiotensin II receptor blocker.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study sample according to hip bearing surface and sex, 2004–2012

| Men |

Women |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bearing surface | MoP | ASR XL | LH MoM | SH MoM (> 32 mm) | MoP (≤ 32 mm) | ASR XL | LH MoM (> 32 mm) | SH MoM (≤ 32 mm) |

| Pre-exclusion cohort: | Men (n = 2,384) | Women (n = 3,213) | ||||||

| Total patients, n (%) | 2,026 (85) | 87 (3.6) | 171 (7.2) | 100 (4.2) | 2,907 (90.5) | 79 (2.5) | 159 (5) | 68 (2.1) |

| Heart failure medicationa | 268 | 12 | 18 | 11 | 413 | 12 | 21 | 7 |

| Heart failure admissiona | 122 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 126 | 3 | 7 | 2 |

| Study cohort: | Men (n = 1,764) | Women (n = 2,255) | ||||||

| Total patients, n (%) | 1,502 (85.1) | 63 (3.6) | 124 (7) | 75 (4.3) | 2,044 (90.1) | 58 (2.6) | 107 (4.7) | 46 (2) |

| Age, median, years | 82.3 | 81.6 | 77.8 | 77.3 | 82.2 | 80.6 | 80.2 | 79.4 |

| IQR | 75.6–85.6 | 68.3–85.1 | 64.2–83.2 | 69.9–82.7 | 78.9–85.2 | 77.9–83.6 | 76.3–84.5 | 76.3–81.2 |

| Age groups, n (%) | ||||||||

| < 55 | 12 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 7 (6) | 2 (3) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| 55–64 | 156 (10.4) | 13 (21) | 27 (22) | 20 (27) | 13 (0.6) | 1 (2) | 6 (6) | 2 (4) |

| 65–74 | 193 (12.8) | 8 (13) | 21 (17) | 13 (17) | 190 (9.3) | 5 (9) | 14 (13) | 5 (11) |

| 75–84 | 705 (46.9) | 26 (41) | 46 (37) | 36 (48) | 1,292 (63.2) | 40 (69) | 64 (60) | 35 (76) |

| ≥ 85 | 436 (29) | 16 (25) | 23 (19) | 4 (5) | 548 (26.8) | 12 (21) | 23 (21) | 3 (7) |

| Fixation, n (%) | ||||||||

| Uncemented | 605 (40.3) | 61 (97) | 73 (59) | 69 (92) | 656 (32.1) | 53 (91) | 61 (57) | 32 (70) |

| Cemented | 897 (59.7) | 2 (3) | 51 (41) | 6 (8) | 1,388 (67.9) | 5 (9) | 46 (43) | 14 (30) |

| Comorbiditiesb, | ||||||||

| median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) | 4.0 (2.0–6.0) | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) | 4.0 (2.0–5.0) | 5.0 (3.0–6.0) | 4.0 (2.0–6.0) | 5.0 (3.0–6.0) | 4.0 (1.0–6.0) |

| n (%) | ||||||||

| 0 | 75 (5) | 5 (8) | 5 (4) | 5 (7) | 132 (6.5) | 3 (5) | 4 (4) | 6 (13) |

| 1 | 108 (7.2) | 6 (9) | 8 (6) | 9 (12) | 111 (5.4) | 7 (12) | 1 (1) | 6 (13) |

| 2 | 181 (12.1) | 6 (9) | 16 (13) | 9 (12) | 185 (9.1) | 6 (10) | 10 (9) | 5 (11) |

| 3 | 204 (13.6) | 11 (18) | 26 (21) | 10 (13) | 281 (13.7) | 9 (16) | 18 (17) | 4 (9) |

| ≥ 4 | 934 (62.1) | 35 (56) | 69 (56) | 42 (56) | 1,335 (65.5) | 33 (57) | 74 (69) | 25 (54) |

MoP: metal-on-polyethylene; ASR: Articular Surface Replacement; LH MoM: large-head metal-on-metal; SH MoM: small-head metal-on-metal; IQR: interquartile range.

Record of admission/dispensed medication in the year prior to the primary THA.

Comorbidities based on RxRisk-V.

Exposure of interest

Exposure groups were created based on the THA bearing surface used in the primary procedure. The bearing surface was ascertained by matching product codes associated with the hip procedure with the Australian Government’s Prosthesis List (2016), which contains a unique billing code for individual prostheses. As the MoP bearing is the most common articulation in THA, this was used as the comparator for MoM THAs. Based on the literature on varying performance and revision rates for different MoM types (Graves et al. 2011), 3 groups of MoM THAs of interest were identified: ASR XL, which has the highest revision rate of all large-head (LH) MoM THAs (AOANJRR SR 2015), other LH MoM THAs, and all small-head (SH) MoM THAs.

Outcome of interest

The main outcome of interest was first hospitalization for heart failure after the primary THA (ICD-10-AM codes I50.0–I50.9 as primary discharge diagnosis). A secondary outcome was all-cause mortality. A sensitivity analysis was performed for the primary analysis, in which we identified heart failure events as hospitalizations with the specified discharge diagnosis codes as either a primary or a secondary diagnosis.

Effect modifiers and confounders

Patient age and sex are associated with development of heart failure. Age and sex were therefore evaluated as confounders and as effect modifiers. Only sex was identified as an effect modifier for the primary outcome (hospitalization for heart failure as a primary diagnosis), so all analyses were stratified by sex. Other covariates considered as possible confounders included type of fixation of the prosthesis (cementless/cement) and comorbidities at baseline, identified by RxRisk-V (Sloan et al. 2003). RxRisk-V is a prescription based comorbidity measure with 45 disease categories; it has been validated as a measure of comorbidity burden (Vitry et al. 2009) (Appendix 1, see Supplementary data).

Statistics

Medians, interquartile ranges, frequencies, and proportions were used to describe the study sample. Survival analyses were conducted for time to first hospitalization for heart failure and for time to death after the primary THA. Patients were censored at the time of death, revision of the hip prosthesis, or admission to hospital for a second primary hip prosthesis. Cumulative incidence curves were used to describe the estimated cumulative probabilities of heart failure stratified by exposure groups and sex, accounting for informative censoring. Cox proportional hazards (PH) models were used to estimate the cause-specific hazard ratio (HR) for hospitalization for heart failure by exposure group. Time at risk of hospitalization for heart failure was measured from day of discharge from the hospital after the THA operation until first hospital admission for heart failure or the end of the study period (June 30, 2014). The Cox PH model was used to examine all-cause mortality by exposure group, stratified by sex and adjusted for age and comorbidities. Confounders were included, based on clinical knowledge and bias assessment using the method for directed acyclic graphs (DAG) outlined by Shrier and Platt (2008) and a DAG graphical tool (Textor et al. 2011) combined with a change in estimate approach. The assumption of proportional hazards for the Cox PH model was confirmed using interactions with time and covariates. SAS version 9.4 was used for all analyses. Any 2-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

4,019 patients were included in the study; 3,546 (88%) received MoP prostheses, 121 (3%) received ASR XL prostheses, 231 (6%) received other LH MoM prostheses, and 121 (3%) received SH MoM prostheses. Baseline characteristics of the cohorts are presented in Table 1 and baseline RxRisk-V in Appendix 1 (see Supplementary data).

Crude incidences of the main and secondary outcomes are presented in Table 2. In men, the proportion who were hospitalized with a primary diagnosis of heart failure was 10/63, 10/124, 4/75, and 114/1,506 in patients who had ASR XL prostheses, other LH MoM prostheses, SH MoM prostheses, and MoP prostheses, respectively. For women, the proportion with heart failure was 2/58 with ASR XL, but otherwise the incidence of heart failure was similar to that in men (6/107 with LH MoM, 2/46 with SH MoM, and 162/2,044 with MoP).

Table 2.

Incidence of hospitalization for heart failure, death, revision surgery, and second total hip replacement (THR) according to hip bearing surface and sex

| Men |

Women |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bearing surface | MoP | ASR XL | LH MoM (> 32 mm) | SH MoM (≤ 32 mm) | MoP | ASR XL | LH MoM (> 32 mm) | SH MoM (≤ 32 mm) |

| (n = 1,502) | (n = 63) | (n = 124) | (n = 75) | (n = 2,044) | (n = 58) | (n = 107) | (n = 46) | |

| Heart failure hospitalization | ||||||||

| primary diagnosis, n (%) | 114 (7.6) | 10 (16) | 10 (8) | 4 (5) | 162 (7.9) | 2 (3) | 6 (6) | 2 (4) |

| primary or secondary diagnosis, n (%) | 270 (18.0) | 18 (29) | 18 (15) | 12 (16) | 322 (15.8) | 11 (19) | 13 (12) | 5 (11) |

| Death, all causes, n (%) | 558 (37.2) | 26 (41) | 34 (27) | 22 (29) | 544 (26.6) | 11 (19) | 23 (22) | 11 (24) |

| Revision surgery, n (%) | 79 (5.3) | 5 (8) | 12 (10) | 7 (9) | 80 (3.9) | 4 (7) | 8 (8) | 3 (7) |

| Second primary THR, n (%) | 146 (9.7) | 9 (14) | 13 (11) | 11 (15) | 199 (9.7) | 12 (21) | 11 (10) | 7 (15) |

| Follow-up, median (IQR)a, years | 6.8 | 7.2 | 6.7 | 7.4 | 6.5 | 6.6 | 6.3 | 9.0 |

| IQR | 6.4–7.2 | 6.4–8.0 | 6.1–7.1 | 6.3–8.6 | 6.3–6.7 | 6.1–7.3 | 6.0–7.1 | 8.5–9.4 |

See Table 1 for abbreviations.

Censored: death, hospitalization for heart failure, second total hip arthroplasty, and revision.

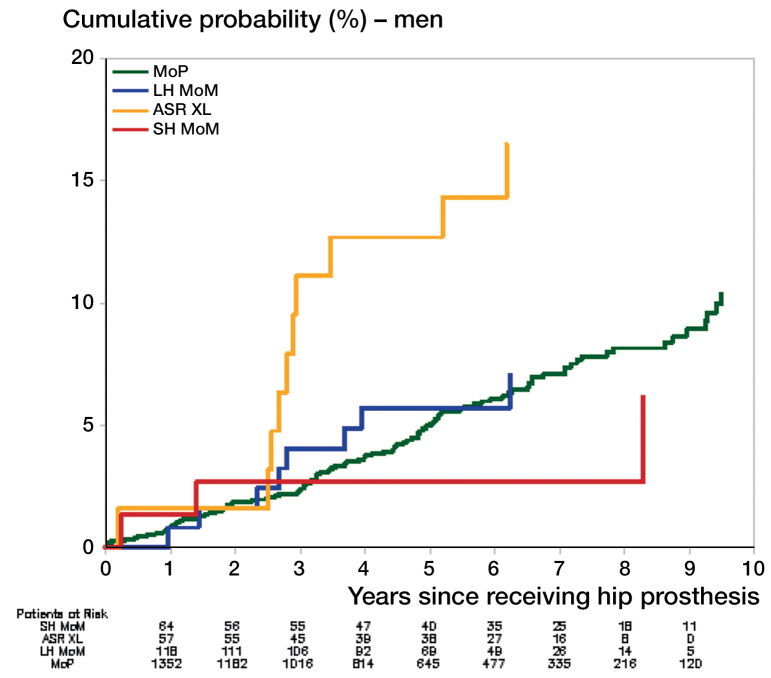

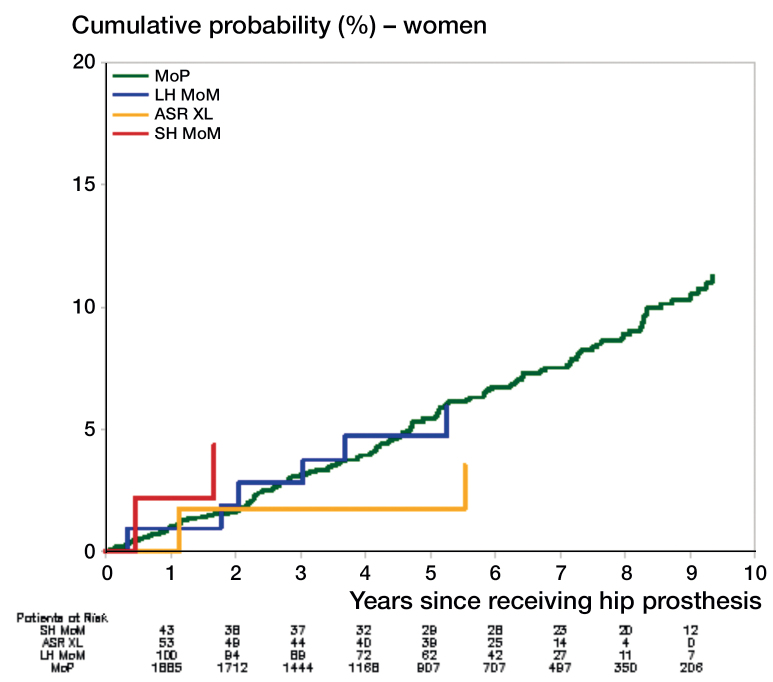

The cumulative probability of hospitalization for heart failure after receiving a THA is shown in Figures 1 and 2. For men, there was a higher rate of hospitalization for heart failure with ASR XL than with MoP (hazard ratio (HR) = 3.2, 95% CI: 1.6–6.5) (Table 3). Compared to MoP, there was no statistically significant difference in the rate of hospitalization for heart failure in men who received SH MoM or other LH MoM THA. Also, compared to MoP there was no significant difference in hospitalization rates for heart failure in women with ASR XL (HR =0.5, 95% CI: 0.1–1.9), or with any other type of MoM THA (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Cumulative probabilities of hospitalization for heart failure in men. See Table 1 for abbreviations.

Figure 2.

Cumulative probabilities of hospitalization for heart failure in women. See Table 1 for abbreviations.

Table 3.

Association between bearing type and heart failure and death in men and women

| Men |

Women |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude HR | Adjusteda HR | Crude HR | Adjustedb HR | |||||

| (95% CI) | (95% CI) | p-value | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | p-value | |||

| Heart failure hospitalizationc – primary diagnosis | ||||||||

| MoP | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| ASR XL | 2.28 (1.19–4.37) | 3.21 (1.59–6.47) | 0.001 | 0.47 (0.12–1.88) | 0.46 (0.12–1.88) | 0.3 | ||

| LH MoM (> 32 mm) | 0.88 (0.43–1.81) | 1.20 (0.58–2.48) | 0.6 | 0.75 (0.33–1.70) | 0.89 (0.39–2.02) | 0.8 | ||

| SH MoM (≤ 32 mm) | 0.52 (0.16–1.63) | 0.94 (0.29–3.06) | 0.9 | 0.44 (0.11–1.76) | 0.67 (0.17–2.73) | 0.6 | ||

| Death, all causes | ||||||||

| MoP | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| ASR XL | 0.95 (0.64–1.41) | 1.15 (0.76–1.72) | 0.5 | 0.65 (0.36–1.19) | 0.69 (0.38–1.28) | 0.2 | ||

| LH MoM (> 32 mm) | 0.65 (0.46–0.92) | 0.88 (0.62–1.24) | 0.5 | 0.80 (0.53–1.21) | 0.93 (0.61–1.42) | 0.8 | ||

| SH MoM (≤ 32 mm) | 0.55 (0.36–0.85) | 0.85 (0.55–1.32) | 0.5 | 0.59 (0.33–1.08) | 0.79 (0.43–1.43) | 0.4 | ||

HR: hazard ratio. See Table 1 for other abbreviations.

Men: Heart failure hospitalization – adjusted for (RxRisk-V) age, cement, arrhythmia, hypertension, ischemic heart disease angina, and ischemic heart disease hypertension. Death – adjusted for (RxRisk-V) age and cement.

Women: Heart failure hospitalization – adjusted for (RxRisk-V) age, arrhythmia, hypertension, and IHD hypertension. Death – adjusted for (RxRisk-V) age and cement.

Note: Cause-specific hazard ratios censored for death, revision, and second hip.

The results were similar to those from the main analysis in the sensitivity analysis, in which both primary and secondary diagnoses were used to identify hospitalizations for heart failure (Appendix 2, see Supplementary data).

Mortality was high for all bearing groups, and higher in men than in women (Table 2). Compared to MoP bearings, no statistically significant difference in mortality was observed for any of the MoM bearings (Table 3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first observational cohort study to identify an association between an adverse systemic health effect, in this case hospital admission for heart failure, and the use of MoM THA. This effect was only observed with 1 type of prosthesis (ASR XL (DePuy)) and was only evident in men. Based on our results, we estimate that after 3 years 1 additional hospitalization for heart failure would have occurred for every 11 (95% CI: 6–109) men treated with an ASR XL prosthesis rather than a MoP prosthesis.

The higher rate of hospitalization for heart failure with ASR XL only is consistent with previous research showing that the ASR XL has the highest revision rate of any LH MoM prosthesis (AOANJRR SR 2015). The higher revision rate with the ASR XL has been attributed to a higher occurrence of metal-related pathology compared to similar prostheses (AOANJRR SR 2015). The identification of a higher rate of heart failure that is specific to this high-risk prosthesis—and not to other MoM THAs—supports the idea that the association between heart failure and the use of the ASR XL is real. An important possible implication of these findings is that other MoM prostheses may also be associated with an increased risk of developing heart failure as time progresses.

There are a number of possible explanations as to why the higher heart failure rate was only observed in men. It is known that the risk of heart failure increases with age, and that men have a higher incidence (Bui et al. 2011). It has been reported that in the DVA population, men have higher rates of hospitalization than women, which is consistent with the idea that most women with full-entitlement benefits are likely to be war widows with no service-related injuries and diseases (Lloyd and Anderson 2008). In our study cohort, mortality was higher for men than for women in all exposure groups. Hence, the sex difference may reflect that the male cohort in this study is a more vulnerable group and as such was more susceptible to development of heart failure following exposure to MoM prostheses than the female cohort. This is consistent with our results, where the hospitalization rate for heart failure was statistically significantly higher for men with MoM hips than for women with MoM hips, whereas there was no significant sex difference in the rate of hospitalization for heart failure in patients with MoP hips (data not shown). In the Quebec heart failure epidemic, most of the heart failures reported after drinking beer with added cobalt occurred in men (Morin et al. 1967, Kesteloot et al. 1968, Sullivan et al. 1969, Alexander 1972). Although it is possible that this phenomenon is due to preferential exposure or other contributory factors such as poor nutritional status, the possibility of greater male susceptibility to the toxic effects of cobalt remains.

While we were unable to associate the occurrence of heart failure directly with raised serum cobalt ion levels in this study, our identification of higher rate of admission for heart failue being confined to the prosthesis that was most at risk is strong circumstantial evidence of a link to raised serum cobalt. Patients with the ASR XL prosthesis and also other large-head MoM THAs have been identified as having raised blood levels of cobalt ions (Hart et al. 2011, Gill et al. 2012, Chang et al. 2013, Hartmann et al. 2013, Jantzen et al. 2013, Randelli et al. 2013), with the levels normalizing after the hip prostheses had been removed (Allen et al. 2014). Blood levels of cobalt are related to wear rate and corrosion of the prosthesis (Vendittoli et al. 2011, Hart et al. 2013). An increase in revision has been associated with increasing blood levels of cobalt (Hart et al. 2014). In patients with an ASR XL THA, a positive correlation between blood levels of cobalt and femoral head size has been reported (Langton et al. 2011). The ASR XL THA has also been associated with a higher rate of revision than other LH MoM prostheses (de Steiger et al. 2011), indicating a greater problem with metal products in the ASR XL prosthesis.

We found no statistically significant difference in rates of hospitalization for heart failure between patients with other MoM hips and patients with MoP hips, but we cannot rule out an association with these prostheses, as only a small number of each type of design and combination was used in the other MoM groups. There is large variability in femoral design, femoral head size, metallurgy, modularity, and acetabular components between implanted MoM prostheses, so revision rates and the potential for metal particle and ion production vary between MoM prostheses (Cheung et al. 2016).

We were unable to adjust for a number of potential confounding factors associated with heart failure events, such as tobacco and alcohol use, obesity, and pre-existing cardiac dysfunction (with preserved or reduced ejection fraction), but we did exclude patients who had been hospitalized previously for heart failure and those who were on medicines likely to be indicative of heart failure. These factors are unlikely to be associated with the type of prosthesis selected by the surgeon, so we have no reason to believe that this would systematically bias our results. Our cohort had a higher median age than the general population who received MoM prostheses, and one of the limitations of our study is that the results are generalizable only to an older patient population. We did adjust for age and baseline comorbidities using the validated comorbidity burden RxRisk-V; the hazard ratio for admission for heart failure following the use of the ASR XL rather than a MoP prosthesis was higher than for the unadjusted result (Table 3). Importantly, heart failure was not an identified risk at the time the treatment decision was made, so it is unlikely that patients were selected to receive a particular bearing surface due to this perceived risk. However, even if confounding by indication did occur, indications for MoM hips were for younger patients and so patients who received MoM hips would probably have a lower risk of developing heart failure than patients who received MoP hips. It might be expected that there would also be an increased mortality risk. Our study population was an older cohort, and consequently the mortality for all groups was high. This may be the explanation for no observed difference. It is also possible that longer follow-up may be required before any difference in mortality is observed. The observation that there was no statistically significant difference in mortality between the exposure groups also indicates that the groups were not different in their overall health status at the time of their primary THA, suggesting that the observed increase in heart failure rate was not due to selection of the ASR XL for sicker patients who were more at risk of experiencing this event.

We used the endpoint of primary discharge diagnosis of heart failure to identify incident heart failure, which would mainly identify patients with the most severe heart failure. This approach may have underestimated the incidence of heart failure (Pfister et al. 2013), resulting in possible misclassification of outcomes, but there is no reason to suspect that this miscalssification would differ between the exposure groups and would have introduced bias in our results. Our sensitivity analysis including both primary and secondary diagnoses of heart failure resulted in an increased proportion of heart failure outcomes, while estimates of relative hazards were similar to the main analysis. Because only a 1-year lookback period for a history of heart failure was used to exclude patients, it is possible that patients with a history of heart failure who were not on medication in the year prior to surgery were not captured. However, if the history of heart failure is under-ascertained in our patients, we have no reason to believe that it was different between the patients with MoM and the patients with MoP—and it is unlikely to have biased our estimations.

Our study had a number of major strengths. The most important was the quality of the data source. Veterans’ adminstrative health data in Australia are comprehensive, and have enabled the examination of a possible temporal relationship between undergoing THA and development of heart failure. Data are available for the type of hip replacement procedure, type of hip prosthesis, hospitalizations for heart failure, mortality, and dispensed medications. The comorbidities of the different groups could be identified and compared using a validated comorbidity measure based on prescribed medicines (RxRisk-V). The totality of the information available was important in avoiding potential bias and confounding in this analysis.

In summary, our study shows that men with a ASR XL THA with no recorded history of heart failure at the time of surgery had a higher rate of hospital admission for heart failure following the THA than men with a MoP THA. Further studies are needed to investigate whether the association can also be found in a younger cohort of patients with these prostheses. While the causality of the relationship remains uncertain, our findings highlight an urgent need for further research to investigate this possibility. It may also have possible implications for the long-term monitoring of people who have received the ASR XL and possibly other MoM hip prostheses.

Supplementary data

Appendices 1 and 2 are available in the online version of this article.

MHG drafted the manuscript, and managed and analyzed the data. NLP extracted the data. All authors were responsible for the design of the study, interpretation of the data, critical revision of the work for important content, and final approval of the version to be published.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the data custodian, the Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA), which provided data for conduction of the study. The DVA reviewed and approved the manuscript but played no role in the analysis and interpretation of the results, or in preparation of the manuscript. The work was supported by an Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre of Research Excellence in Post-Marketing Surveillance of Medicines and Medical Devices grant (GNT1040938). NLP is supported by NHMRC grant GNT1035889. EER is supported by NHMRC grant GNT 1110139. The funders of the study had no role in the design and conduction of the study; in collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; in preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. None of the authors report having competing interests that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

References

- Guidelines for the prevention, detection and management of chronic heart failure in Australia. National Heart Foundation of Australia and the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand (Chronic Heart Failure Guidelines Expert Writing Panel); 2011. ISBN 978-1-921748-71-4. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR). Annual Report. Adelaide; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry, supplementary report (AOANJRR SR). Metal on Metal Bearing Surface Total Conventional Hip Arthroplasty. Adelaide; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- The Prostheses List. Australian Government Department of Health; 2016. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/health-privatehealth-prostheseslist.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander C S. Cobalt-beer cardiomyopathy. A clinical and pathologic study of twenty-eight cases. Am J Med 1972; 53 (4): 395–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen L A, Ambardekar A V, Devaraj K M, Maleszewski J J, Wolfel E E.. Clinical problem-solving. Missing elements of the history. N Engl J Med 2014; 370 (6): 559–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui A L, Horwich T B, Fonarow G C.. Epidemiology and risk profile of heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2011; 8 (1): 30–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J R, Estey M P.. Metal release from hip prostheses: cobalt and chromium toxicity and the role of the clinical laboratory. Clin Chem Lab Med 2013; 51 (1): 213–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang E Y, McAnally J L, Van Horne J R, Van Horne J G, Wolfson T, Gamst A, Chung C B.. Relationship of plasma metal ions and clinical and imaging findings in patients with ASR XL metal-on-metal total hip replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95 (22): 2015–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung A C, Banerjee S, Cherian J J, Wong F, Butany J, Gilbert C, Overgaard C, Syed K, Zywiel M G, Jacobs J J, Mont M A.. Systemic cobalt toxicity from total hip arthroplasties: review of a rare condition Part 1 - history, mechanism, measurements, and pathophysiology. Bone Joint J 2016; 98-B (1): 6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D. How safe are metal-on-metal hip implants? BMJ 2012; 344: e1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Steiger R N, Hang J R, Miller L N, Graves S E, Davidson D C.. Five-year results of the ASR XL Acetabular System and the ASR Hip Resurfacing System: an analysis from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93 (24): 2287–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin J J, Pomerleau A C, Brent J, Morgan B W, Deitchman S, Schwartz M.. Clinical features, testing, and management of patients with suspected prosthetic hip-associated cobalt toxicity: a systematic review of cases. J Med Toxicol 2013; 9 (4): 405–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fary C, Thomas G E, Taylor A, Beard D, Carr A, Glyn-Jones S.. Diagnosing and investigating adverse reactions in metal on metal hip implants. BMJ 2011; 343: d7441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessner B D, Steck T, Woelber E, Tower S S.. A systematic review of systemic cobaltism after wear or corrosion of chrome-cobalt hip implants. J Patient Saf 2015; Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill H S, Grammatopoulos G, Adshead S, Tsialogiannis E, Tsiridis E.. Molecular and immune toxicity of CoCr nanoparticles in MoM hip arthroplasty. Trends Mol Med 2012; 18 (3): 145–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves S E, Rothwell A, Tucker K, Jacobs J J, Sedrakyan A.. A multinational assessment of metal-on-metal bearings in hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93Suppl3: 43–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart A J, Sabah S A, Bandi A S, Maggiore P, Tarassoli P, Sampson B, J A S. . Sensitivity and specificity of blood cobalt and chromium metal ions for predicting failure of metal-on-metal hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93 (10): 1308–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart A J, Muirhead-Allwood S, Porter M, Matthies A, Ilo K, Maggiore P, Underwood R, Cann P, Cobb J, Skinner J A.. Which factors determine the wear rate of large-diameter metal-on-metal hip replacements? Multivariate analysis of two hundred and seventy-six components. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95 (8): 678–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart A J, Sabah S A, Sampson B, Skinner J A, Powell J J, Palla L, Pajamaki K J, Puolakka T, Reito A, Eskelinen A.. Surveillance of Patients with Metal-on-Metal Hip Resurfacing and Total Hip Prostheses: A Prospective Cohort Study to Investigate the Relationship Between Blood Metal Ion Levels and Implant Failure. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96 (13): 1091–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann A, Hannemann F, Lutzner J, Seidler A, Drexler H, Gunther K P, Schmitt J.. Metal ion concentrations in body fluids after implantation of hip replacements with metal-on-metal bearing–systematic review of clinical and epidemiological studies. PLoS ONE 2013; 8 (8): e70359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hug K T, Watters T S, Vail T P, Bolognesi M P.. The withdrawn ASR THA and hip resurfacing systems: how have our patients fared over 1 to 6 years? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471 (2): 430–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantzen C, Jorgensen H L, Duus B R, Sporring S L, Lauritzen J B.. Chromium and cobalt ion concentrations in blood and serum following various types of metal-on-metal hip arthroplasties: a literature overview. Acta Orthop 2013; 84 (3): 229–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesteloot H, Roelandt J, Willems J, Claes J H, Joossens J V.. An enquiry into the role of cobalt in the heart disease of chronic beer drinkers. Circulation 1968; 37 (5): 854–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon Y M, Lombardi A V, Jacobs J J, Fehring T K, Lewis C G, Cabanela M E.. Risk stratification algorithm for management of patients with metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty: consensus statement of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, and the Hip Society. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96 (1): e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton D J, Jameson S S, Joyce T J, Hallab N J, Natu S, Nargol A V.. Early failure of metal-on-metal bearings in hip resurfacing and large-diameter total hip replacement: A consequence of excess wear. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92 (1): 38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton D J, Jameson S S, Joyce T J, Gandhi J N, Sidaginamale R, Mereddy P, Lord J, Nargol A V.. Accelerating failure rate of the ASR total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93 (8): 1011–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton D J, Sidaginamale R P, Joyce T J, Natu S, Blain P, Jefferson R D, Rushton S, Nargol A V.. The clinical implications of elevated blood metal ion concentrations in asymptomatic patients with MoM hip resurfacings: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2013; 3 (3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne M, Belzile E L, Roy A, Morin F, Amzica T, Vendittoli P. A. Comparison of whole-blood metal ion levels in four types of metal-on-metal large-diameter femoral head total hip arthroplasty: the potential influence of the adapter sleeve. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93 Suppl 2: 128–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd J, Anderson P.. Veterans’ use of health services In: Aged care series no13 Veterans’ use of health services. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra: AIHW; 2008, http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id =6442468071. [Google Scholar]

- Machado C, Appelbe A, Wood R.. Arthroprosthetic cobaltism and cardiomyopathy. Heart Lung Circ 2012; 21 (11): 759–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X, Wong A A, Crawford R W.. Cobalt toxicity–an emerging clinical problem in patients with metal-on-metal hip prostheses? Med J Aust 2011; 194 (12): 649–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin Y, Daniel P.. Quebec beer-drinkers’ cardiomyopathy: etiological considerations. Can Med Assoc J 1967; 97 (15): 926–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin Y L, Foley A R, Martineau G, Roussel J.. Quebec beer-drinkers’ cardiomyopathy: forty-eight cases. Can Med Assoc J 1967; 97 (15): 881–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandit H, Glyn-Jones S, McLardy-Smith P, Gundle R, Whitwell D, Gibbons C L, Ostlere S, Athanasou N, Gill H S, Murray D W.. Pseudotumours associated with metal-on-metal hip resurfacings. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90 (7): 847–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfister R, Michels G, Wilfred J, Luben R, Wareham N J, Khaw K T.. Does ICD-10 hospital discharge code I50 identify people with heart failure? A validation study within the EPIC-Norfolk study. Int J Cardiol 2013; 168 (4): 4413–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice J R, Clark M J, Hoggard N, Morton A C, Tooth C, Paley M N, Stockley I, Hadjivassiliou M, Wilkinson J M.. Metal-on-metal hip prostheses and systemic health: a cross-sectional association study 8 years after implantation. PLoS ONE 2013; 8 (6): e66186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randelli F, Banci L, Favilla S, Maglione D, Aliprandi A.. Radiographically undetectable periprosthetic osteolysis with ASR implants: the implication of blood metal ions. J Arthroplasty 2013; 28 (8): 1259–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson B, Hart A.. Clinical usefulness of blood metal measurements to assess the failure of metal-on-metal hip implants. Ann Clin Biochem 2012; 49 (Pt 2): 118–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrier I, Platt R W.. Reducing bias through directed acyclic graphs. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008; 8: 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan K L, Sales A E, Liu C F, Fishman P, Nichol P, Suzuki N T, Sharp N D.. Construction and characteristics of the RxRisk-V: a VA-adapted pharmacy-based case-mix instrument. Med Care 2003; 41 (6): 761–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan J F, Egan J D, George R P.. A distinctive myocardiopathy occurring in Omaha, Nebraska: clinical aspects. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1969; 156 (1): 526–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Textor J, Hardt J, Knuppel S.. DAGitty: a graphical tool for analyzing causal diagrams. Epidemiology 2011; 22 (5): 745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tower S S. Arthroprosthetic cobaltism: neurological and cardiac manifestations in two patients with metal-on-metal arthroplasty: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92 (17): 2847–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendittoli P A, Amzica T, Roy A G, Lusignan D, Girard J, Lavigne M.. Metal Ion release with large-diameter metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26 (2): 282–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitry A, Wong S A, Roughead E E, Ramsay E, Barratt J.. Validity of medication-based co-morbidity indices in the Australian elderly population. Aust N Z J Public Health 2009; 33 (2): 126–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zywiel M G, Cherian J J, Banerjee S, Cheung A C, Wong F, Butany J, Gilbert C, Overgaard C, Syed K, Jacobs J J, Mont M A.. Systemic cobalt toxicity from total hip arthroplasties: review of a rare condition Part 2. measurement, risk factors, and step-wise approach to treatment. Bone Joint J 2016; 98-B (1): 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]