Abstract

Background and purpose — Telemedicine could allow patients to be discharged more quickly after surgery and contribute to improve fast-track procedures without compromising quality, patient safety, functionality, anxiety, or other patient-perceived parameters. We investigated whether using telemedicine support (TMS) would permit hospital discharge after 1 day without loss of self-assessed quality of life, loss of functionality, increased anxiety, increased rates of re-admission, or increased rates of complications after hip replacement.

Patients and methods — We performed a randomized controlled trial involving 72 Danish patients in 1 region who were referred for elective fast-track total hip replacement between August 2009 and March 2011 (654 were screened for eligibility). Half of the patients received a telemedicine solution connected to their TV. The patients were followed until 1 year after surgery.

Results — Length of stay was reduced from 2.1 days (95% CI: 2.0–2.3) to 1.1 day (CI: 0.9–1.4; p < 0.001) with the TMS intervention. Health-related quality of life increased in both groups, but there were no statistically significant differences between groups. There were also no statistically significant differences between groups regarding timed up-and-go test and Oxford hip score at 3-month follow-up. At 12-month follow-up, the rates of complications and re-admissions were similar between the groups, but the number of postoperative hospital contacts was lower in the TMS group.

Interpretation — Length of postoperative stay was shortened in patients with the TMS solution, without compromising patient-perceived or clinical parameters in patients undergoing elective fast-track surgery. These results indicate that telemedicine can be of value in fast-track treatment of patients undergoing total hip replacement.

Fast-track regimes can reduce hospital length of stay (LOS) (Gulotta et al. 2011, Pivec et al. 2012, Kehlet. 2013, Glassou et al. 2014, Winther et al. 2015). Reduced LOS, however, makes it more challenging for healthcare providers to logistically coordinate tasks involving education and training of the patients. The physical and psychological stress response of the patient on the first day postoperatively—often combined with intake of opioids (Krenk et al. 2012)—challenges practical education and increases learning difficulties in patients.

In fast-track total hip replacement (THR) procedures, preoperative education of the patients has become standard (Husted et al. 2010b, Raphael et al. 2011, Gulotta et al. 2011). Different guidelines on how to make written information understandable have been described (Rud et al. 2006, NHS 2010). Reviews have concluded that there is little evidence to support the use of preoperative education in THR and total knee replacement procedures (McDonald et al. 2004, Aydin et al. 2015). There have been no studies examining the use of telemedicine support (TMS) in conjunction with THR and its effects on LOS, adverse outcome, physical outcome, anxiety, hip-related function, pain, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

We conducted a study to determine whether a novel and multifaceted TMS intervention would facilitate early discharge of patients undergoing THR without negative effects on clinical safety, physical outcomes, and patient-reported outcomes. Here we report the results of this randomized, controlled clinical trial with consecutive enrollment of patients who were referred for elective fast-track total hip replacement and with 12-month follow-up. We describe the effect of the novel TMS platform used as intervention.

Patients and methods

We performed a randomized, controlled clinical trial with 12-month follow-up. We consecutively enrolled patients who were undergoing elective fast-track THR. The novel TMS platform was used as the intervention.

The Remote Rehabilitation and Support project and the randomized clinical trial took place at the orthopedic department of a Danish urban teaching hospital from August 2009 through February 2012. The study was performed in accordance with the CONSORT Statement. Patients who were planned to undergo first-time elective THR were consecutively invited to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were a distance to the hospital of more than 60 km, previous hip surgery of any kind, mental disability, inability to communicate in Danish, having no support person, and having no internet connection.

Telemedicine intervention

Organizational innovation and the development of the telemedicine support were based on a need-driven innovation and participatory design approach (Greenbaum and Kyng 1991). The intervention was performed in cooperation with CareTech Innovation, which is part of Alexandra Institute, Aarhus University, Denmark. It involved computer scientists, ethnographers, and architects. The needs addressed were documented using observation studies and interviews with patients and relatives.

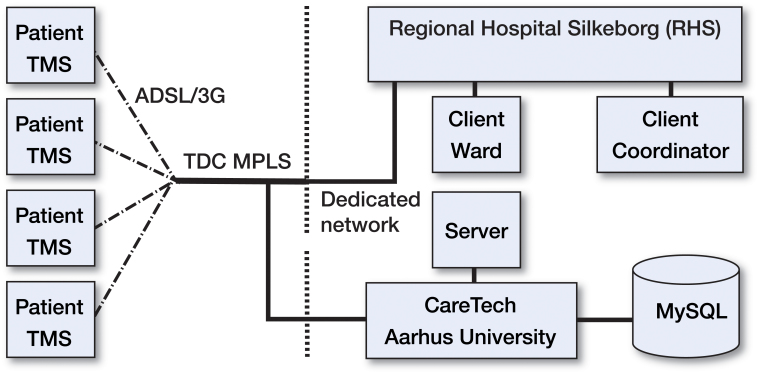

A dedicated network from Silkeborg Regional Hospital (RHS) was connected to a multi-protocol label-switching (MPLS) network (Figure 1). The server, located at CareTech, used the same MPLS and the connection to each patient’s home made use of an ADSL internet connection. At the patient’s home we use a Wi-Fi network using a Check Point Wi-Fi router (Check Point Software Technologies Inc., San Carlos, CA) dedicated to the telemedicine solution.

Figure 1.

The network used in the RRS study

Logistic limitations and needs for optimizing the standard fast-track procedure were defined by staff from all departments working with fast-track THR. This was done in a multidisciplinary workshop. Participants defined just below 200 specific ways of optimizing the existing fast-track procedures. As part of the innovation and design process, hardware and software prototypes were developed and presented for patients and healthcare providers. Most prototypes were rejected at an early stage. The main goal of the information material was to address as many of the patients’ needs as possible. We created the material to match a possible low degree of health literacy (Gazmararian et al. 1999), focusing on the use of visualization and minimal use of text, and included elements of exposure and computer-aided cognitive behavioral therapy (Kaltenthaler et al. 2006) to minimize preoperative anxiety; we used the Illeris model for learning (Illeris 2008) (Table 1).

Table 1.

The telemedicine solution worked as a box for the TV set and covered the material listed

| Interactive written information | With added speak and visualizations |

| Animation | A narrative story with elements of exposure. Described the background of primary hip arthritis, the anatomy of the hip, the surgical procedure, the importance of rehabilitation, risks, and limitations |

| Films of all recommended exercises | Simply described and with a supportive speak. |

| Films of how to use supplementary aids | Simply described and with a supportive speak. |

| Films of how to do daily tasks | Getting up and down from the floor, in and out of bed, in and out of a car, and so on. |

| Medicine | An interactive overview of prescribed medicine. What to take and when. Pictures and descriptions of each type of medication |

| Radiography | Pre- and postoperative radiographs |

| Video conference | Could be initiated by either the patient or the hospital. Camera was mobile and could be used for close-ups. |

Patient sample and procedure

Eligible patients were randomized to either a control group or an intervention group approximately 14 days before surgery. This was done after obtaining written informed consent from both the patient and the support person. The randomization procedure was handled by an external person who had no contact with the patients, and was performed by drawing opaque and sealed envelopes. A physiotherapist coordinated the patient pathway (Table 2) and functioned as a contact person for all patients. The control group followed the standard fast-track plan and the intervention group followed the new TMS plan developed for this study.

Table 2.

Procedures in the 2 arms of the RCT

| Fast-track THR only | Telemedicine support | |

|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Surgery | Surgery |

| Day 1 | Training and rehabilitation | Discharge to home |

| Day 2 | Discharge to home | Video conference |

| Day 3 | Visit by physiotherapist | |

| Day 6 | Video conference | |

| Day 21 | Visit to outpatient clinic | Visit to outpatient clinic |

| Day 90 | Visit to outpatient clinic | Visit to outpatient clinic |

A surgeon, an anesthesiologist, and a nurse individually informed all the patients at the outpatient clinic on the day that it was decided to perform a THR. All patients were invited to and participated in a 2-hour group information meeting an average of 14 days before surgery. After the information meeting, the patients were informed about the outcome of the randomization. The patients were then introduced to the content of the study and the data collection procedure. The intervention group was introduced to the telemedicine platform and some of its features. They were instructed on how to set up the telemedicine solution in their home and how to use it. They were also informed about the goal of one day of hospitalization, and they were informed that we would try to motivate them but not force them to achieve that goal. They were informed that the use of the telemedicine support was voluntary but that it would be relevant for them to see some of the information films before surgery.

The patients were hospitalized at the same ward on the day of surgery. The same surgeon performed all operations. Spinal anesthesia was used for all patients, and wound infiltration was done during the final stage of the operation. The goals regarding treatment of blood loss, pain, and nausea—as well as nutritional advice and mobilization—were identical for all patients, and followed the Danish guidelines for THR.

At the outpatient clinic, the patients were seen by the physiotherapist. The patients using TMS returned the telemedicine equipment on day 90 and the internet connection was terminated. The primary outcome measure (LOS) was validated using the electronic health record. Among the supplementary outcomes were HRQoL, assessed with EQ-5D-3L. The Oxford hip score (OHS) was used to assess hip-related function and pain; function and pain was scored from baseline (2 weeks preoperatively) to the follow-up visit at 12 months. Furthermore, timed up-and-go (TUG) (Podsiadlo and Richardson 1991) and anxiety measured in mm on a visual analog scale (VAS) were recorded from baseline to the follow-up visit 3 months later. To evaluate a range of psychological problems and symptoms of psychopathology that could theoretically affect the outcome, we used the validated symptom check-list 90 R (SCL-90-R) (Olsen et al. 2004) at baseline. Data were collected in a study folder, which was returned at the 3-month follow-up. Data from follow-up at 6 and 12 months were obtained from the patients by post. Information about complications was validated using the Danish online e-Health Portal, (www.Sundhed.dk), accessible through the local electronic health record.

Statistics

Calculation of sample size was based on a simulation of LOS. The simulation was based on distribution of patients and maximum LOS was set at 5 days. The calculations resulted in a sample size of 74. Primary outcome measure LOS is reported as median (range) and difference in HRQoL was evaluated with repeated measurement analysis (Wilks’ lambda) whereas most secondary outcomes are reported as mean and 95% confidence interval. Any p-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Secondary outcome measures were tested for equal development of mean over time by repeated measurement analysis and are presented as Wilks’ lambda p-value. Where relevant, Student’s t-test was used. Non-parametric outcomes were compared using a 2-sample Mann-Whitney test. EpiData version 3.1 (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark) was used for data entry. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA software version 10.0.

Ethics and registration

The study followed the standards for Good Clinical Practice and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. This study did not require approval by an ethics committee, according to Danish law. The study was registered with the Danish Data Protection Agency (entry no. 2009-41-3394) and at Clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT00969020).

Results

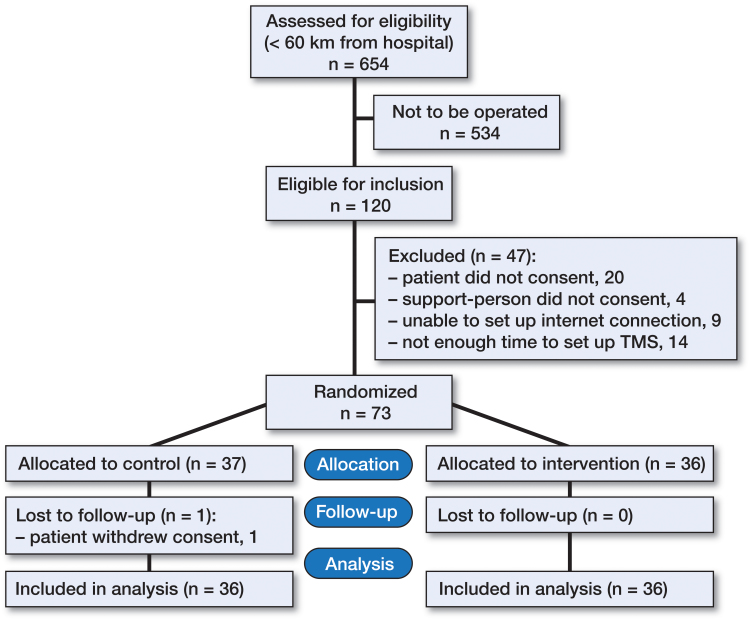

73 patients were enrolled from August 2009 until March 2011 (Figure 2, Table 3). In 1 case, the internet connection failed but the patient continued in the study. 1 patient in the control group withdrew from the study before surgery.

Figure 2.

Flow of patients during the study period.

Table 3.

Baseline data

| Fast-track THR only | Telemedicine support | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex: F/M, n | 17/19 | 17/19 |

| Agea, years | 64 (45–84) | 63 (43–80) |

| Distancea, km | 40 (1.8–57) | 33 (0.4–57) |

| Implant type (n = 72) | ||

| Corail/BHR | 29/7 | 31/5 |

| Marital status (n = 66) | ||

| Alone/with partner | 5/27 | 2/32 |

| Job status (n = 66) | ||

| Working | 11 | 19 |

| On sick leave | 0 | 2 |

| Retired | 20 | 13 |

| Other | 1 | 0 |

| SCL-90Ra (n = 70) | ||

| GSI | 47 (44–50) | 47 (43–50) |

| PST | 48 (44–51) | 46 (43–49) |

| PSDI | 45 (40–50) | 51 (47–56) |

Median (range).

BHR: Birmingham Hip Resurfacing; GSI: global severity index.

PST: positive symptom total; PSDI: positive symptom distress index.

Hospitalization (Table 4)

Table 4.

Distribution of length of stay (LOS) for all patients

| Group | 1 day | 2 days | 3 days | 4 days | 5 days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast-track THR only (n = 36) | 8 | 26 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Telemedicine support (n = 36) | 34 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Median LOS was 2 (1–4) days with standard fast-track total hip replacement (FTHR) surgery and care; TMS intervention reduced LOS to a median of 1 day (1–5). With the Mann-Whitney test, the result was statistically significant (p < 0.001). The reduction in mean LOS was 0.72 days (CI: 0.42–1.02; p < 0.001) with intention to treat.

HRQoL

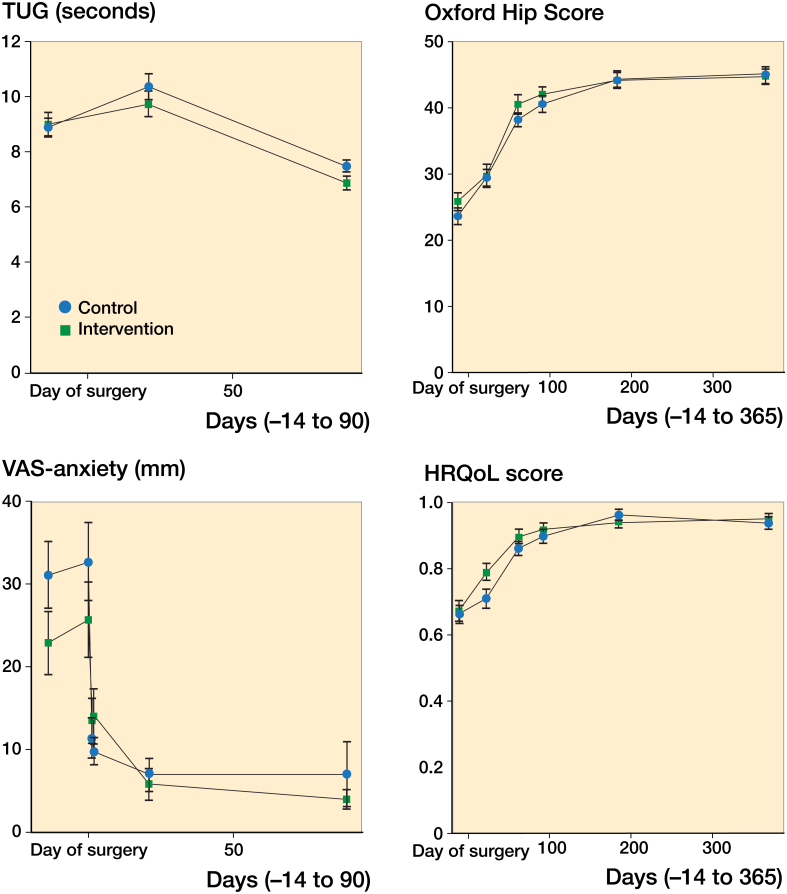

Both groups had a clinical and statistically significant gain in HRQoL from baseline to 12-month follow-up. The mean gained for the control group was 0.26 (CI: 0.19–0.33; p < 0.001). For the intervention group, the mean gain in HRQoL was 0.28 (CI: 0.2–0.34; p < 0.001). The mean difference between the 2 groups at 12 months was −0.01 (CI: −0.063 to 0.036; p < 0.6). We did not find any statistically significant difference in HRQoL between the groups, as evaluated with a repeated measurement analysis for the entire data collection period (Wilks’ lambda p-value =0.4) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Outcomes over time.

Safety

Mean re-admission events were similar in the 2 groups. 1 TMS patient with fever was admitted but no deep infection was found, and the patient was discharged with antibiotics after 3 days of observation. The demands on resources required by answering patient-related enquiries by telephone calls and unplanned visits to the hospital are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Unplanned contacts with the hospital. Values are mean (range)

| Fast-track THR only | Telemedicine support | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of telephone calls from patient | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | 0.92 (0.56–0.73) | 0.04 |

| No. of extra visits to hospital | 0.31 (0.04–0.57) | 0.17 (−0.01 to 0.34) | 0.4 |

| No. of re-admissions | 0 | 0.03 (−0.03 to 0.08) | 0.3 |

Anxiety

We found a statistically significant reduction in anxiety from baseline to 90 days after surgery. The mean reduction for all patients was 25 mm (CI: 19–32; p < 0.001). We found similar scores for VAS anxiety between the groups, as evaluated with a repeated measurement analysis for the entire period of the data collection (Wilk’s lambda p-value =0.3) (Figure 3).

Oxford hip score

Both groups had a statistically significant gain in OHS from baseline to 12-month follow-up. The mean gain for the control group was 21 (CI: 18–24; p < 0.001). For the intervention group, the mean gain was 19 (CI: 16–22; p < 0.001). The mean difference between the 2 groups at 12 months was 0.39 (CI: −2.1 to 2.9; p = 0.8). We found similar OHS in both groups, as evaluated with a repeated measurement analysis for the entire data collection period (Wilks’ lambda p-value =0.7) (Figure 3).

Timed up-and-go

Both groups had a statistically significant gain in TUG from baseline to 3-month follow-up. The mean gain for the control group was 1.4 seconds (CI: 0.91–1.93; p < 0.001). For the intervention group, the mean gain was 2.1 seconds (CI: 1.4–2.7; p < 0.001). The mean difference between the 2 groups at 3 months was 0.6 seconds (CI: −0.05 to 1.26; p = 0.07). We found similar TUG for the groups, as evaluated with a repeated measurement analysis for the entire data collection period (Wilk’s lambda p-value =0.09) (Figure 3).

Discussion

This study including follow-up at 12 months showed that using telemedicine and evidence-based education in connection with fast-track THR reduced length of stay, with no changes in rates of complications or re-admissions. The results also indicated that tasks and responsibilities for care can be assigned to patients without weakening the patients’ perceptions of an improved HRQoL. LOS cannot be regarded as a single primary outcome (Larsen et al. 2008), but must be seen in relation to other outcome measures. To emphasize the importance of maintaining quality of treatment, we selected HRQoL as a primary outcome together with LOS. All outcomes in our study indicated that the 2 groups had a similar positive development over time, with some insignificant differences in favor of telemedicine support.

The fast-track procedure in THR has gained a strong foothold in the northern European countries, where patients are normally discharged directly to their own home (Husted et al. 2011). The overall re-admission rate for THR in Denmark in 2011 was 5.4% (Overgaard 2012). No clear link has been found between short LOS and rate of re-admission (Husted et al. 2010a, Pivec et al. 2012, Glassou et al. 2014). 2 American studies have indicated that there is a connection between a decrease in LOS and an increase in the rates of discharge to post-acute care and re-admission rates of up to 25% in the USA (Cram et al. 2011, Wolf et al. 2012). We have found no explanation for these differences between countries.

It is difficult to conclude that the existing patient education program met the needs of the patients and there relatives. The program did follow the guidelines, and was evaluated extensively and considered "best practice" by the research group. Also, it is not possible to determine whether it was the new content, the way the content was distributed, or a combination of both that led to the results obtained with the TMS.

We have not found any papers that have documented the effect of telemedicine in patients undergoing THR. 1 study on patients undergoing a total knee replacement (TKR) found that "participants in the tele-rehabilitation group achieved outcomes comparable to those of the conventional rehabilitation group" at 6 weeks (Russell et al. 2011).

We learned about the patients’ needs using observational studies and interviews. With that knowledge, we made a visual and simple interactive telemedicine solution containing educational material inspired by the Illeris model for learning (Illeris 2008) and a didactic method accommodating anxiety, degree of health literacy, and elements of computer-aided cognitive behavioral therapy. The simplicity of the support, the emphasis on selecting and presenting information based on needs, and the possibility of creating close personal contact between the healthcare providers and the patient might explain our findings. The better connection between patient and hospital, and easy access to information, may be the reasons for being able to discharge 94% of the TMS patients on day 1 after major surgery—without any increase in adverse effects and with a lower number of contacts with the hospital compared to the control group.

Our study, using novel technology as part of a multifaceted intervention, had many limitations. We tried to minimize selection bias using broad inclusion criteria and consecutive inclusion. Of the outpatient clinic patients who lived closer than 60 km from the hospital, almost 90% were excluded because they were not candidates for hip surgery. Of the candidates, close to 20% refused to participate—and we do not know the cause. Patients who declined to participate may not have felt comfortable using a telemedicine solution. The risk of being randomized to be discharged after only 1 day of hospitalization might also feel challenging for some patients. Thus, we most likely studied a selected group of patients with a higher level of self-efficacy.

We found it impossible to establish blinding in this study, except from when conducting the TUG test. Those who conducted TUG were not informed about the patients’ randomization before testing. With TUG, we used a physical test that might not be regarded as first choice in patients undergoing THR with an average age of 63 years (Bohannon 2006). But we found it easy to use, and chose to do the last test 3 months after surgery when the recovery period could still affect the outcome. The use of questionnaires and data from the electronic health record also minimized bias. We tried to avoid a contamination effect. However, ruling out of a contamination effect—for example, by not favoring the control group—was not possible. The discharge criteria were identical in both groups, and the staff were well informed. The decision about whether a patient fulfilled the criteria was managed by a small group of healthcare providers. The patients were informed about the criteria, and knew that they could stay in hospital if they were not ready to be discharged, but no-one wished to stay after being encouraged to leave. The fact that some patients in the control group were discharged after only 1 day indicates that the guidelines were followed. The TMS group was informed about the use of the solution preoperatively, and had seen the animation of the procedure before filling in baseline data. We believe that the tendency to have a lower level of anxiety and better HRQoL at baseline in the TMS group can be explained by this. A small pilot test including patients undergoing THR with preoperative education confirmed this tendency. Patients who saw the animations after receiving preoperative education scored better on anxiety (on VAS) than those who do not. We are now conducting a study on a new and updated version of the TMS, with more animations. We have no explanation for the difference in the distribution of patients who had a job or were retired. However, this may have influenced the results in favor of the intervention.

There are many topics to be assessed in future fast-track studies (Kehlet and Soballe 2010). No previous studies appear to have addressed the need for more research using an evidence-based approach to educate fast-track patients, the effect of actively including relatives or support persons in fast-track procedures, the need for studies on organizational innovation, or the need for research in the use of health-IT or telemedicine in connection with fast-track procedures.

Most governments in the western world have included health-IT and digitalization of the healthcare system as a way of reducing costs and reducing waste (Blumenthal 2009, EU. 2010), and such knowledge is now being shared (European Commision, Bhanoo 2010, Blumenthal and Dixon, 2012). More researchers, clinicians, and decision-makers must recognize that health-IT can create new ways of treating diseases—including orthopedic conditions. There is a need for more and stronger evidence, a focus on health technology assessments, and inclusion of different research methods to innovate and meet healthcare challenges. We hope that this study will inspire researchers to look into the use of telemedicine for patients with orthopedic conditions, and also in other areas of surgery that have a strong need for education, rehabilitation, and support. We believe that it is possible to maintain high quality and to perhaps reduce length of stay and the risk of readmission even more.

MSV had full access to all of the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: MSV, SM, ML, and KS. Obtaining of funding: MSV, SM. Acquisition of data: MSV. Analysis and interpretation of data: MSV, ML, JL, PUP, and LBJ. Statistical analysis: MSV. Drafting of the manuscript: MSV, ML, JL, PUP, and LBJ. Critical revision of the manuscript: MSV, MSV, ML, JL, PUP, and LBJ.

This work was supported by grants from CareTech Innovation through the European Regional Development Fund, ERDF, and the Fund for Clinical Research, Central Denmark Region and the Animation Hub through the Danish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Higher Education.

MSV is taking part in a start-up company, developing animations for education of healthcare providers, patients, and relatives.

References

- Aydin D, Klit J, Jacobsen S, Troelsen A, Husted H.. No major effects of preoperative education in patients undergoing hip or knee replacement - a systematic review. Dan Med J 2015; 62 (7): A5106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhanoo S. Denmark leads the way in digital care. New York Times 2010; National edition: D5. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal D. Stimulating the adoption of health information technology. N Engl J Med 2009; 360 (15): 1477–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal D, Dixon J.. Health-care reforms in the USA and England: Areas for useful learning. Lancet 2012; 380 (9850): 1352–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon R W. Reference values for the timed up and go test: A descriptive meta-analysis. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2006; 29 (2): 64–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cram P, Lu X, Kaboli P J, Vaughan-Sarrazin M S, Cai X, Wolf B R, Li Y.. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of medicare patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty, 1991-2008. JAMA 2011; 305 (15): 1560–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EU. Digital agenda for Europe: What would it do for me?. 2010; http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-10-199_en.htm [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2012 transatlantic health-IT/e-Health co-operation assembly. 2012; https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/2012-transatlantic-health-itehealth-co-operation-assembly [Google Scholar]

- Gazmararian J A, Baker D W, Williams M V, Parker R M, Scott T L, Green D C, Fehrenbach S N, Ren J, Koplan J P.. Health literacy among medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. JAMA 1999; 281 (6): 545–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassou E N, Pedersen A B, Hansen T B.. Risk of re-admission, reoperation, and mortality within 90 days of total hip and knee arthroplasty in fast-track departments in denmark from 2005 to 2011. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (5): 493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum J, Kyng M.. Design at work: Cooperative design of computer systems. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gulotta L V, Padgett D E, Sculco T P, Urban M, Lyman S, Nestor B J.. Fast track THR: One hospital’s experience with a 2-day length of stay protocol for total hip replacement. HSS J 2011; 7 (3): 223–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Otte K S, Kristensen B B, Orsnes T, Kehlet H.. Readmissions after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010a; 130 (9): 1185–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Solgaard S, Hansen T B, Soballe K, Kehlet H.. Care principles at four fast-track arthroplasty departments in denmark. Dan Med Bull 2010b; 57 (7): A4166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Lunn T H, Troelsen A, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kristensen B B, Kehlet H.. Why still in hospital after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty? Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (6): 679–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illeris K. Contemporary theories of learning. Taylor & Francis, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenthaler E, Brazier J, De Nigris E, Tumur I, Ferriter M, Beverley C, Parry G, Rooney G, Sutcliffe P.. Computerised cognitive behaviour therapy for depression and anxiety update: A systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2006; 10 (33): iii, xi,xiv, 1-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehlet H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Lancet 2013; 381 (9878): 1600–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehlet H, Soballe K.. Fast-track hip and knee replacement–what are the issues? Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (3): 271–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenk L, Rasmussen L S, Hansen T B, Bogo S, Soballe K, Kehlet H.. Delirium after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth 2012; 108 (4): 607–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen K, Hansen T B, Soballe K.. Hip arthroplasty patients benefit from accelerated perioperative care and rehabilitation: A quasi-experimental study of 98 patients. Acta Orthop 2008; 79 (5): 624–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald S, Hetrick S, Green S.. Pre-operative education for hip or knee replacement(review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; (1): CD003526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS. Written information: General guidance. 2010; http://www.nhsidentity.nhs.uk/tools-and-resources/patient-information/written-information%3A-general-guidance [Google Scholar]

- Olsen L R, Mortensen E L, Bech P.. The SCL-90 and SCL-90R versions validated by item response models in a danish community sample. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004; 110 (3): 225–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overgaard S. Danish hip arthroplasty register. Annual report 2011. http://www.dhr.dk/annual_report.htm [Google Scholar]

- Pivec R, Johnson A J, Mears S C, Mont M A.. Hip arthroplasty. Lancet 2012; 380 (9855): 1768–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsiadlo D, Richardson S.. The timed "up & go": A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991; 39 (2): 142–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raphael M, Jaeger M, van Vlymen J.. Easily adoptable total joint arthroplasty program allows discharge home in two days. Can J Anaesth 2011; 58 (10): 902–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rud K, Jakobsen D, Svejgaard A. Vejledning til udarbejdelse af information til patienter (guidelines for the preparation of information to patients). 2006; https://www.rigshospitalet.dk/…/Vejledning-til-udarbejdelse-Inf… [Google Scholar]

- Russell T G, Buttrum P, Wootton R, Jull G A.. Internet-based outpatient telerehabilitation for patients following total knee arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93 (2): 113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundhed.dk. The Danish e-health portal. https://www.sundhed.dk/ [Google Scholar]

- Winther S B, Foss O A, Wik T S, Davis S P, Engdal M, Jessen V, Husby O S.. 1-year follow-up of 920 hip and knee arthroplasty patients after implementing fast-track. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (1): 78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf B R, Lu X, Li Y, Callaghan J J, Cram P.. Adverse outcomes in hip arthroplasty: Long-term trends. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94 (14): e103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]