Abstract

Background and purpose — Recent evidence has questioned the effect of arthroscopic knee surgery for middle-aged and older patients with degenerative meniscal tears with or without concomitant radiographic knee osteoarthritis (OA). We investigated the prevalence of early or more established knee OA and patients’ characteristics in a cohort of patients undergoing arthroscopic surgery for a meniscal tear.

Patients and methods — 641 patients assigned for arthroscopy on suspicion of meniscus tear were consecutively recruited from February 2013 through January 2015. Of these, 620 patients (mean age 49 (18–77) years, 57% men) with full datasets available were included in the present study. Prior to surgery, patients completed questionnaires regarding onset of symptoms, duration of symptoms, and mechanical symptoms along with the knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS). At arthroscopy, the operating surgeon recorded information about meniscal pathology and cartilage damage. Early or more established knee OA was defined as the combination of self-reported frequent knee pain, cartilage damage, and the presence of degenerative meniscal tissue.

Results — 43% of patients (269 of 620) had early or more established knee OA. Of these, a large proportion had severe cartilage lesions with almost half having a severe cartilage lesion in at least 1 knee compartment.

Interpretation — Based on a definition including frequent knee pain, cartilage damage, and degenerative meniscal tissue, early or more established knee OA was present in 43% of patients undergoing knee arthroscopy for meniscal tear.

Arthroscopic surgery is widely used to treat meniscal tears in middle-aged and older adults (Cullen et al. 2009, Kim et al. 2011, Thorlund et al. 2014, Hamilton and Howie 2015). A recent registry-based study including information from plain radiographs, MRI, and arthroscopy found that about one-third of knee arthroscopies in Sweden were performed on patients with degenerative meniscal tears and/or osteoarthritis (Bergkvist et al. 2016). This is despite the fact of systematic reviews reporting no added benefit of surgery over that of placebo or additional effect of surgery in addition to exercise therapy for patients with early signs of knee osteoarthritis (OA) (i.e. degenerative meniscal tear) or radiographic knee osteoarthritis (Khan et al. 2014, Thorlund et al. 2015). Degenerative meniscal tears and knee OA are very common in the general middle-aged and elderly population (Englund et al. 2008, Pereira et al. 2011). The proportion of middle-aged and older patients being treated with arthroscopic surgery in Denmark is high, and has been reported to have increased in the period between 2000 and 2011 (Thorlund et al. 2014, Hare et al. 2015). This suggests similar patterns of practice in Denmark and Sweden.

Factors such as onset of symptoms (i.e. traumatic vs. non-traumatic) and the presence of “mechanical symptoms” are considered important indications for surgery in the middle-aged and elderly population (Stuart and Lubowitz 2006, Jevsevar et al. 2014, Krych et al. 2014, Lee et al. 2014). Furthermore, specific types of tear patterns have been suggested to be typical of degenerative and traumatic meniscal tears (Poehling et al. 1990, Englund et al. 2008, Bergkvist et al. 2016). Detailed information about meniscal tear pattern and other knee pathology collected at arthroscopy can help characterize patients who undergo meniscal surgery.

The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of early and more established knee OA in a cohort of patients undergoing surgery for a meniscal tear. We also wanted to investigate possible differences in meniscal pathology such as pattern of tear, cartilage damage, and pattern of symptoms in patients with and without early or more established knee OA.

Patients and methods

Participants

This study included participants from the Knee Arthroscopy Cohort, Southern Denmark (KACS) (Thorlund et al. 2013). KACS was a prospective cohort study following patients undergoing knee arthroscopy for a meniscal tear who were recruited at 4 public hospitals in Denmark between February 1, 2013 and January 31, 2014 and also at 1 of the 4 hospitals in the period from February 1, 2014 to January 31, 2015.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: being ≥18 years of age, being assigned to knee arthroscopy on suspicion of a meniscal tear by an orthopedic surgeon (i.e. based on clinical examination, history of injury, and MRI result if available), being able to read and understand Danish, and having an e-mail address.

The exclusion criteria were: having no meniscal tear at surgery, having previous or planned anterior or posterior cruciate ligament (ACL or PCL) reconstruction surgery in either knee, having had fracture(s) in the lower extremities within the 6 months before recruitment, or not being able to reply to the questionnaire because of mental impairment.

Patient-reported outcomes

Information about patient characteristics and symptoms was collected using online questionnaires at a median of 7 (IQR: 3–10) days before surgery.

Symptom duration, symptom onset, and mechanical symptoms

Prior to surgery, the patients answered the following questions concerning the duration of symptoms and the type of onset of symptoms: “How long have you had your knee pain/knee problems for which you are now having surgery?” (with response options ranging from “0–3 months” to “more than 24 months”), “How did the knee pain/problems for which you are now having surgery develop? (choose the answer that best matches your situation)” (with response options “The pain/problems have slowly developed over time”, “As a result of a specific incident (i.e. kneeling, sliding, and/or twisting of the knee or the like)”, and “As a result of a violent incident (i.e. during sports, a crash, or a collision or the like)”). Furthermore, the patients reported the presence and frequency of mechanical symptoms (i.e. the sensation of catching or locking of the knee): “How often have you experienced catching or locking of the knee that is about to undergo surgery?” (with response options ranging from “never” to “daily”).

Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS)

Patients completed the KOOS, which is a knee-specific questionnaire used to assess patient-reported outcomes. The KOOS consists of 5 subscales: pain, symptoms, activities of daily living (ADL), sport and recreation function (Sport/Rec), and knee-related quality of life (QoL) (Roos et al. 1998b). Each subscale ranges from 0 to 100 points, with 0 representing extreme knee problems and 100 representing no knee problems. The KOOS is intended to be used for patients with knee injuries that can result in posttraumatic OA—i.e. meniscus injury, ACL injury, chondral injury etc. (Roos et al. 1998b). The KOOS has been validated in several populations, including patients undergoing arthroscopic meniscal surgery (Roos et al. 1998a, b, Roos et al. 1999, Roos and Toksvig-Larsen 2003), and to assess self-reported outcomes in this group of patients (Herrlin et al. 2007, Herrlin et al. 2013).

Structural pathology at arthroscopy

Information about meniscal pathology (i.e. meniscal tissue quality, compartment, tear pattern, radial location, and type of surgery) and cartilage damage was recorded by the operating surgeon at arthroscopy. Meniscal tears were classified using a modified version of the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine (ISAKOS) classification of meniscal tears (Anderson et al. 2011) and cartilage lesions were classified using the International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) grading system (Brittberg and Winalski 2003). The ICRS cartilage score ranges from 0 to 4 with 0 representing normal cartilage and 4 representing very severe cartilage lesions. Information registered by surgeons on the modified ISAKOS questionnaire was transferred from paper format to electronic format using automated forms processing. This method has been validated as an alternative to double entry of data (Paulsen et al. 2012). If more than one meniscal tear was present, the largest one was used for analysis.

Presence/absence of early or more established knee OA

Early or more established knee OA, based on findings at arthroscopy and patient symptoms, was determined using a modified algorithm proposed by Luyten et al. (2012), with the aim of identifying only those with early knee OA. In this study, we included patients who were considered to have early knee OA and those who had more severe cartilage damage—and therefore considered to have more established knee OA. In this study, we defined the presence of early or more established knee OA as the combination of frequent knee pain (“daily” or “always” using a single item from the KOOS pain subscale), degenerative meniscal tissue (assessed by the surgeon), and cartilage damage (i.e. ICRS grade I in at least 2 knee joint compartments or at least ICRS grade II in 1 compartment). For the latter, all single ICRS scores for each knee joint compartment were added together to give a total ICRS score. We also calculated the proportion of patients with a combination of traumatic symptoms and non-degenerative meniscus tissue at arthroscopy.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics are given as means and standard deviation (SD), medians with interquartile range (IQR), or numbers with percentages as appropriate. Differences in patient characteristics between patients with and without knee OA were tested using unpaired t-test, chi-squared test, or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Stata 14.1 was used for all statistical analyses and any p-value of 0.05 or less was considered to be statistically significant.

Ethics

All the patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study, even though the Regional Scientific Ethics Committee of Southern Denmark waived the need for ethical approval after reviewing the outline of KACS (Thorlund et al. 2013).

Results

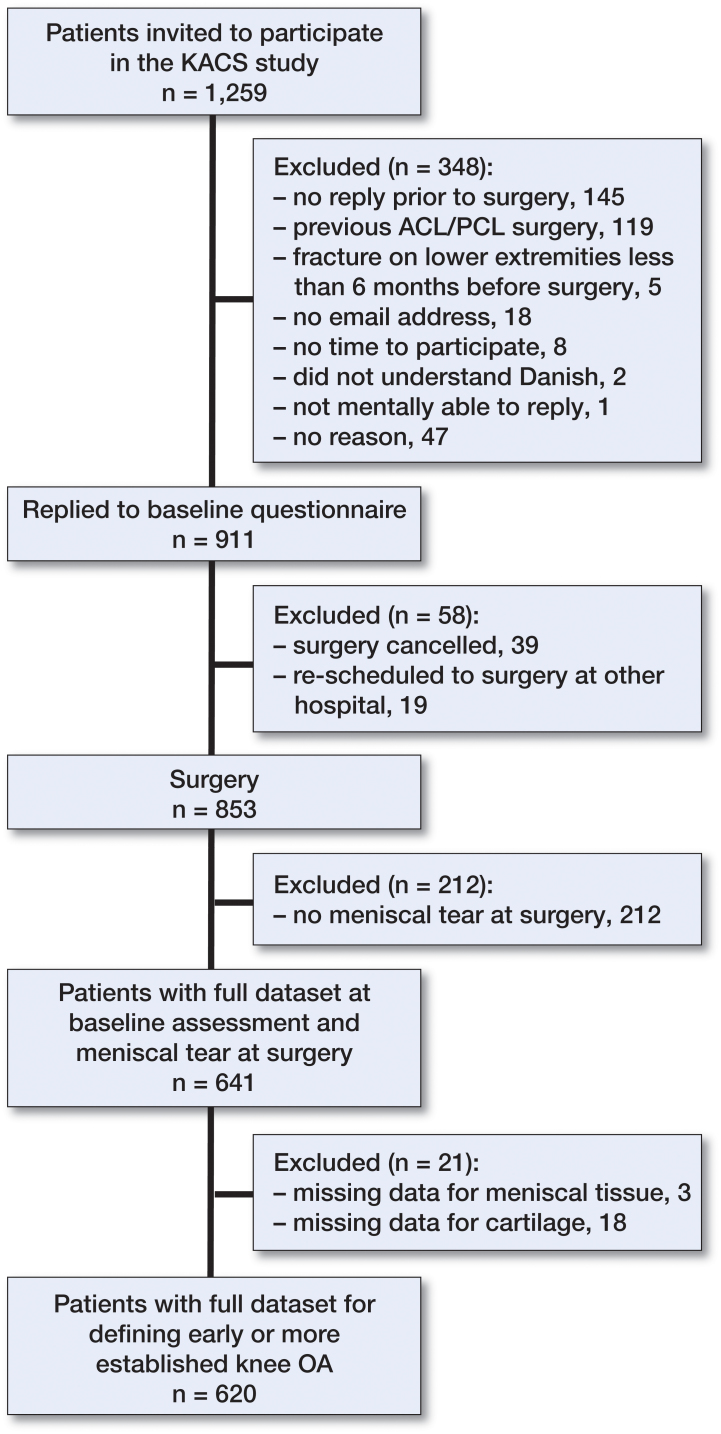

641 patients constituted the baseline sample of the KACS cohort (i.e. replied to the preoperative questionnaire and had a meniscal tear at surgery) (Figure 1). Of these patients, 97% had full datasets available for analysis on the prevalence of early or more established knee OA. The 21 patients who were excluded due to missing data on categorization as having knee OA were similar in terms of age, body mass index (BMI), and sex distribution (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of inclusion.

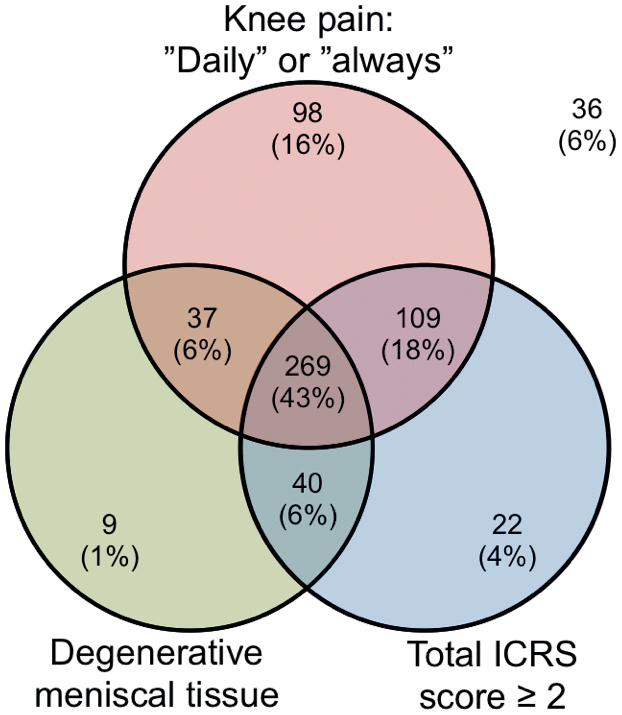

Early or more established knee OA (as defined) was present in 43% of the patients (Figure 2). Of those patients with no knee OA, only 36 did not have any of the features included in the algorithm to define early or more established knee OA. On average, the patients with early or more established knee OA were older and slightly heavier than the patients without OA (Table 1). 15% of patients reported having a traumatic symptom onset in combination with having non-degenerative meniscal tissue quality.

Figure 2.

Venn diagram with proportion of early or more established knee OA defined by presence of frequent knee pain, degenerative meniscal tissue, and total International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) score.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Variables | Patients with knee OA (n = 269) range | Patients without knee OA (n = 351) range | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (SD) | 57 (9.1) | (29–77) | 44 (13) | (18–76) | < 0.001 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 132 (49) | 135 (39) | 0.008 | ||

| Height, cm (SD) | 174 (9.1) | (155–200) | 176 (9.4) | (152–201) | 0.002 |

| Weight, kg (SD) | 86 (17) | (50–149) | 83 (15) | (48–135) | 0.03 |

| BMI (SD) | 28 (4.7) | (20–47) | 27 (4.0) | (19–44) | < 0.001 |

OA: osteoarthritis.

About half of all patients reported having had symptoms for 6 months or less, which did not differ significantly between those with early or more established knee OA and those without knee OA. Mechanical symptoms were more frequent in patients with early or more established knee OA than in those without knee OA (Table 2). The majority of patients without knee OA had non-degenerative meniscal tissue. Longitudinal-vertical tears were also more prevalent in those patients than in the group with early or more established knee OA, which—in contrast—had a higher prevalence of complex tears (Table 3).

Table 2.

Description of patient symptoms

| Variables | Patients with knee OA (n = 269) | Patients without knee OA (n = 351) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of symptoms, n (%) | 0.2 | ||

| 0–3 months | 48 (18) | 76 (22) | |

| 4–6 months | 90 (33) | 87 (25) | |

| 7–12 months | 53 (20) | 76 (22) | |

| 13–24 months | 37 (14) | 55 (16) | |

| > 24 months | 41 (15) | 57 (16) | |

| Symptom onset, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Slowly developed over time | 110 (41) | 89 (25) | |

| Semi-traumatic | 116 (43) | 135 (38) | |

| Traumatic | 43 (16) | 127 (36) | |

| Mechanical symptoms a, n (%) | 0.02 | ||

| Never | 139 (52) | 164 (47) | |

| Monthly | 31 (11) | 71 (20) | |

| Weekly | 22 (8) | 27 (8) | |

| Several times a week | 35 (13) | 52 (15) | |

| Daily | 42 (16) | 37 (11) | |

| Frequent knee painb, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Never | 0 | 9 (3) | |

| Monthly | 0 | 28 (8) | |

| Weekly | 0 | 70 (20) | |

| Daily | 208 (77) | 193 (55) | |

| Always | 61 (23) | 51 (15) | |

| KOOS scores, mean (95% CI) | |||

| Pain | 49 (47–51) | 59 (57–61) | < 0.001 |

| Symptoms | 56 (54–59) | 63 (61–65) | < 0.001 |

| ADL | 57 (55–60) | 69 (67–71) | < 0.001 |

| Sport/Rec | 21 (19–23) | 30 (28–33) | < 0.001 |

| QoL | 40 (38–42) | 43 (41–45) | 0.02 |

OA: Osteoarthritis; ADL: activities of daily living;

Sport/Rec: sport and recreational activities.

The sensation of catching or locking of the knee.

Single item from the KOOS pain subscale.

Table 3.

Knee pathology at arthroscopy

| Variables | Patients with knee OA (n = 269) | Patients without knee OA (n = 351) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of surgery, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Resection | 269 (100) | 311 (89) | |

| Repair | 0 (0) | 33 (9) | |

| Both | 0 (0) | 7 (2) | |

| Meniscal tissue quality, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Non-degenerative | 0 (0) | 245 (70) | |

| Degenerative | 269 (100) | 86 (24) | |

| Undetermined | 0 (0) | 20 (6) | |

| Compartment, n (%) | 0.07 | ||

| Medial | 208 (77) | 253 (72) | |

| Lateral | 35 (13) | 70 (20) | |

| Both | 26 (10) | 28 (8) | |

| Tear pattern, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Longitudinal-vertical a | 16 (6) | 101 (29) | |

| Horizontal | 27 (10) | 15 (4) | |

| Radial | 16 (6) | 25 (7) | |

| Vertical flap | 65 (24) | 77 (22) | |

| Horizontal flap | 11 (4) | 18 (5) | |

| Complex | 107 (40) | 68 (19) | |

| Root tear | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | |

| More than 1 tear pattern | 26 (10) | 46 (13) | |

| Radial location b, n (%) | 0.3 | ||

| Posterior | 192 (71) | 214 (62) | |

| Posterior + mid-body | 38 (14) | 65 (19) | |

| Posterior + anterior | 1 (1) | 1 (0) | |

| Mid-body | 19 (7) | 35 (10) | |

| Anterior + mid-body | 3 (1) | 6 (2) | |

| Anterior | 9 (3) | 11 (3) | |

| All | 7 (3) | 15 (4) | |

| ICRS cartilage grade, n (%) | |||

| Medial compartment | < 0.001 | ||

| Grade 0 | 6 (2) | 172 (49) | |

| Grade 1 | 58 (22) | 88 (25) | |

| Grade 2 | 68 (25) | 48 (14) | |

| Grade 3 | 103 (38) | 36 (10) | |

| Grade 4 | 34 (13) | 7 (2) | |

| Lateral compartment | < 0.001 | ||

| Grade 0 | 48 (18) | 215 (61) | |

| Grade 1 | 106 (39) | 100 (28) | |

| Grade 2 | 67 (25) | 25 (7) | |

| Grade 3 | 36 (13) | 9 (3) | |

| Grade 4 | 12 (5) | 2 (1) | |

| Patellofemoral compartment | < 0.001 | ||

| Grade 0 | 24 (9) | 204 (58) | |

| Grade 1 | 82 (30) | 85 (24) | |

| Grade 2 | 70 (26) | 34 (10) | |

| Grade 3 | 66 (25) | 23 (7) | |

| Grade 4 | 27 (10) | 5 (1) |

OA: osteoarthritis; ICRS: International Cartilage Repair Society.

Extension is a bucket handle tear.

Missing data for patients without OA (n = 4).

Of those patients with early or more established knee OA, only 5% had the minimum required total ICRS score of 2, corresponding to minor cartilage abnormalities. The majority of patients had severe cartilage lesions (i.e. total ICRS score of 7 or higher). This corresponded to 1 severe cartilage lesion (ICRS cartilage score of ≥3) in at least 1 knee joint compartment (Table 4).”

Table 4.

Total ICRS scores in patients with early or more established knee OA

| Variable | Patients with knee OA (n = 269) |

|---|---|

| Total ICRS score, n (%) | |

| 2 | 14 (5) |

| 3 | 48 (18) |

| 4 | 30 (11) |

| 5 | 28 (10) |

| 6 | 43 (16) |

| 7 | 34 (13) |

| 8 | 33 (12) |

| 9 | 26 (10) |

| 10 | 7 (3) |

| 11 | 5 (2) |

| 12 | 1 (0) |

OA: osteoarthritis;

ICRS: International Cartilage Repair Society.

Discussion

In this consecutively recruited observational cohort, we found that 43% of patients undergoing meniscal surgery had signs of early or more established knee OA based on a definition including frequent knee pain, presence of cartilage damage, and degenerative meniscal tissue. Patients with early or more established knee OA had a higher prevalence of complex meniscal tears, more severe cartilage defects, and reported more pronounced pain, symptoms, and impaired function than patients without knee OA.

Most arthroscopic meniscal surgery is carried out in middle-aged and elderly patients (Cullen et al. 2009, Lazic et al. 2014, Thorlund et al. 2014), who typically present with slowly developing symptoms or onset of symptoms after minor trauma (Poehling et al. 1990, Englund et al. 2008, Bergkvist et al. 2016). Most of these patients have degenerative meniscal tears (Thorlund et al. 2014, Bergkvist et al. 2016), a condition associated with incipient knee OA in the middle-aged and elderly population (Englund 2008, Englund et al. 2009). At least one-third of knee arthroscopies in Sweden are performed on patients with degenerative meniscal tears and/or radiological (i.e. radiographic or MRI-based) knee OA (Bergkvist et al. 2016). We found in this study that there was early or more established knee OA in 43% of patients.

Only 15% of patients reported having traumatic symptoms and had a non-degenerative meniscus lesion in an otherwise healthy meniscus, indicative of a “true” traumatic tear. Our findings should be interpreted in the light of recent systematic reviews of randomized trials (Khan et al. 2014, Thorlund et al. 2015), reporting no added benefit of surgery over that of placebo or additional effect of surgery in addition to exercise therapy. The finding of no added benefit was consistent in middle-aged and older patients in the entire continuum from patients with degenerative meniscal tears and no radiographic knee OA to patients with severe radiographic knee OA, i.e. patients similar to those with early or more established knee OA in the present study.

The presence of mec hanical symptoms is often said to be an important indication for knee arthroscopy, especially in middle-aged and elderly patients (Stuart and Lubowitz 2006, Jevsevar et al. 2014, Krych et al. 2014, Lee et al. 2014). We found that about half of all patients reported having mechanical symptoms (i.e. the sensation of catching and/or locking of the knee), with a higher frequency in patients with early or more established knee OA than in those without knee OA. Importantly, a recent secondary analysis of a randomized trial found no added benefit of arthroscopic surgery over sham surgery in relieving self-reported mechanical symptoms (Sihvonen et al. 2016a). Furthermore, an observational study of more than 900 patients undergoing arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for degenerative meniscal tears did not find better improvement in self-reported pain or quality of life in patients with mechanical symptoms than in those without mechanical symptoms (Sihvonen et al. 2016b). These findings call into question self-reported mechanical symptoms as an important indication for meniscal surgery in middle-aged and elderly patients.

In the non-degenerative meniscus, longitudinal-vertical (i.e. bucket handle) tears are more prevalent and are usually observed in younger active individuals, and can be attributed to a specific incident (e.g. sports-related trauma) (Poehling et al. 1990, Bergkvist et al. 2016), whereas complex tears and horizontal tears are more often observed in the degenerative meniscus, typically in the middle-aged and older population (Poehling et al. 1990, Englund et al. 2008, Bergkvist et al. 2016). In general, our study confirms these observations. However, despite the fact that substantially more patients had a traumatic symptom onset among those without knee OA than among those with early or more established knee OA, the duration of symptoms was not significantly different between the 2 groups.

We cannot rule out the possibility of misclassification and thereby over- or underestimation of the prevalence of early or more established knee OA in our cohort of patients undergoing meniscal surgery. In addition to the criteria suggested by Luyten et al. (2012) to identify patients with early knee OA, we also included the concomitant presence of degenerative meniscal tissue together with a more strict pain criterion (i.e. daily knee pain as opposed to at least 2 episodes of knee pain for >10 days within the previous year) to increase specificity and minimize representation of patients with traumatic cartilage damage. Thus, we believe that the criteria used in our study were more likely to underestimate than overestimate the prevalence of early or more established knee OA. Female sex, higher age, overweight, and complex tears were more prevalent in those with early or more established knee OA than in those without knee OA. These factors have previously been associated with knee OA (Poehling et al. 1990, Lawrence et al. 2008, Zakkak et al. 2009, Bergkvist et al. 2016), supporting the ability of our criteria to discriminate between patients with and patients without early or more established knee OA.

We did not have information about the presence/absence of radiographic knee OA, which could have been useful to compare the construct of “more established knee OA” to radiographic knee OA.

We consider our results to be applicable to the general population of patients undergoing meniscal surgery in Denmark, since patients were included consecutively at 4 public hospitals, there were limited exclusion criteria, and there were few missing data on the patients. Furthermore, the demographics of the patients included—with regard to sex and age—are similar to what has been reported for patients undergoing meniscal surgery in Denmark (Thorlund et al. 2014).

In summary, using criteria to define early or more established knee OA that included the presence of cartilage damage and degenerative meniscal tissue scored at arthroscopy, together with frequent knee pain reported by the patient (i.e. daily or always), we found that early or more established knee OA was present in 43% of patients in our cohort who underwent knee arthroscopy for a meniscal tear. Patients categorized as having early or more established knee OA were generally older, had a higher BMI, and had meniscal tear patterns typically associated with knee OA. These characteristics are similar to those of patients who have recently been reported to experience no or marginal short-term effect of arthroscopic partial meniscectomy compared to placebo surgery.

KP, ME, LSL, and JBT conceived and designed the study. NN, UJ, and JS participated in the setup of the study, in patient recruitment, and in data collection. KP, ME, LSL, and JBT conducted the analysis and/or interpretation. KP and JBT drafted the first version of the manuscript. All the authors helped in revising the manuscript.

We would like to acknowledge the efforts of all participating patients and orthopedic surgeons, nurses, and secretaries at the Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, Odense University Hospital (Odense and Svendborg) and the Department of Orthopedics, Lillebaelt Hospital (Kolding and Vejle).

The authors have no competing interests to declare. This study was supported by an individual postdoctoral grant to JBT from the Danish Council for Independent Research/Medical Sciences and with funds from the Region of Southern Denmark.

References

- Anderson A F, Irrgang J J, Dunn W, Beaufils P, Cohen M, Cole B J, Coolican M, Ferretti M, Glenn R E Jr., Johnson R, Neyret P, Ochi M, Panarella L, Siebold R, Spindler K P, Ait Si Selmi T, Verdonk P, Verdonk R, Yasuda K, Kowalchuk D A.. Interobserver reliability of the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine (ISAKOS) classification of meniscal tears. Am J Sports Med 2011; 39 (5): 926–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergkvist D, Dahlberg L E, Neuman P, Englund M.. Knee arthroscopies: who gets them, what does the radiologist report, and what does the surgeon find? Acta Orthop 2016; 87 (1): 12–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittberg M, Winalski C S.. Evaluation of cartilage injuries and repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85-ASuppl2: 58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen K A, Hall M J, Golosinskiy A.. Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. Natl Health Stat Report 2009; (11): 1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund M. The role of the meniscus in osteoarthritis genesis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2008; 34 (3): 573–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund M, Guermazi A, Gale D, Hunter D J, Aliabadi P, Clancy M, Felson D T.. Incidental meniscal findings on knee MRI in middle-aged and elderly persons. N Engl J Med 2008; 359 (11): 1108–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund M, Guermazi A, Roemer F W, Aliabadi P, Yang M, Lewis C E, Torner J, Nevitt M C, Sack B, Felson D T.. Meniscal tear in knees without surgery and the development of radiographic osteoarthritis among middle-aged and elderly persons: The Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60 (3): 831–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton D F, Howie C R.. Knee arthroscopy: influence of systems for delivering healthcare on procedure rates. BMJ 2015; 351: h4720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare K B, Vinther J H, Lohmander L S, Thorlund J B.. Large regional differences in incidence of arthroscopic meniscal procedures in the public and private sector in Denmark. BMJ Open 2015; 5 (2): e006659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrlin S, Hallander M, Wange P, Weidenhielm L, Werner S.. Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2007; 15 (4): 393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrlin S V, Wange P O, Lapidus G, Hallander M, Werner S, Weidenhielm L.. Is arthroscopic surgery beneficial in treating non-traumatic, degenerative medial meniscal tears? A five year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013; 21 (2): 358–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jevsevar D S, Yates A J Jr., Sanders J O.. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med 2014; 370 (13): 1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M, Evaniew N, Bedi A, Ayeni O R, Bhandari M.. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative tears of the meniscus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2014; 186 (14): 1057–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Bosque J, Meehan J P, Jamali A, Marder R.. Increase in outpatient knee arthroscopy in the United States: a comparison of National Surveys of Ambulatory Surgery, 1996 and 2006. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93 (11): 994–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krych A J, Carey J L, Marx R G, Dahm D L, Sennett B J, Stuart M J, Levy B A.. Does arthroscopic knee surgery work? Arthroscopy 2014; 30 (5): 544–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence R C, Felson D T, Helmick C G, Arnold L M, Choi H, Deyo R A, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Hochberg M C, Hunder G G, Jordan J M, Katz J N, Kremers H M, Wolfe F.. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58 (1): 26–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazic S, Boughton O, Hing C, Bernard J.. Arthroscopic washout of the knee: a procedure in decline. Knee 2014; 21 (2): 631–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Hong H, Kim J.. Segmentation of anterior cruciate ligament in knee MR images using graph cuts with patient-specific shape constraints and label refinement. Comput Biol Med 2014; 55: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luyten F P, Denti M, Filardo G, Kon E, Engebretsen L.. Definition and classification of early osteoarthritis of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2012; 20 (3): 401–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen A, Overgaard S, Lauritsen J M.. Quality of data entry using single entry, double entry and automated forms processing–an example based on a study of patient-reported outcomes. PLoS One 2012; 7 (4): e35087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira D, Peleteiro B, Araujo J, Branco J, Santos R A, Ramos E.. The effect of osteoarthritis definition on prevalence and incidence estimates: a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011; 19 (11): 1270–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehling G G, Ruch D S, Chabon S J.. The landscape of meniscal injuries. Clin Sports Med 1990; 9 (3): 539–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos E M, Toksvig-Larsen S.. Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) - validation and comparison to the WOMAC in total knee replacement. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003; 1: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos E M, Roos H P, Ekdahl C, Lohmander L S.. Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)–validation of a Swedish version. Scand J Med Sci Sports 1998a; 8 (6): 439–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos E M, Roos H P, Lohmander L S, Ekdahl C, Beynnon B D.. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)–development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1998b; 28 (2): 88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos E M, Roos H P, Lohmander L S.. WOMAC Osteoarthritis Index–additional dimensions for use in subjects with post-traumatic osteoarthritis of the knee. Western Ontario and MacMaster Universities. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1999; 7 (2): 216–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sihvonen R, Englund M, Turkiewicz A, Jarvinen T L.. Mechanical symptoms and arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in patients with degenerative meniscus tear: a secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2016a; 164 (7): 449–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sihvonen R, Englund M, Turkiewicz A, Jarvinen T L.. Mechanical symptoms as an indication for knee arthroscopy in patients with degenerative meniscus tear: a prospective cohort study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart M J, Lubowitz J H.. What, if any, are the indications for arthroscopic debridement of the osteoarthritic knee? Arthroscopy 2006; 22 (3): 238–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorlund J B, Christensen R, Nissen N, Jorgensen U, Schjerning J, Porneki J C, Englund M, Lohmander L S.. Knee Arthroscopy Cohort Southern Denmark (KACS): protocol for a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2013; 3 (10): e003399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorlund J B, Hare K B, Lohmander L S.. Large increase in arthroscopic meniscus surgery in the middle-aged and older population in Denmark from 2000 to 2011. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (3): 287–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorlund J B, Juhl C B, Roos E M, Lohmander L S.. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee: systematic review and meta-analysis of benefits and harms. BMJ 2015; 350: h2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakkak J M, Wilson D B, Lanier J O.. The association between body mass index and arthritis among US adults: CDC’s surveillance case definition. Prev Chronic Dis 2009; 6 (2): A56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]