Abstract

Twelve percent of 853 California ground squirrels (Spermophilus beecheyi) from six different geographic locations in Kern County, Calif., were found to be shedding on average 44,482 oocysts g of feces−1. The mean annual environmental loading rate of Cryptosporidium oocysts was 57,882 oocysts squirrel−1 day−1, with seasonal patterns of fecal shedding ranging from <10,000 oocysts squirrel−1 day−1 in fall, winter, and spring to levels of 2 × 105 oocysts squirrel−1 day−1 in summer. Juveniles were about twice as likely as adult squirrels to be infected and shed higher concentrations of oocysts than adults did, with particularly high levels of infection and shedding being found among juvenile male squirrels. Based on DNA sequencing of a portion of the 18S small-subunit rRNA gene, there existed three genotypes of Cryptosporidium species in these populations of squirrels (Sbey03a, Sbey03b, and Sbey03c; accession numbers AY462231 to AY462233, respectively). These unique DNA sequences were most closely related (96 to 97% homology) to porcine C. parvum (AF115377) and C. wrairi (AF115378). Inoculating BALB/c neonatal mice with up to 10,000 Sbey03b or Sbey03c fresh oocysts from different infected hosts did not produce detectable levels of infection, suggesting that this common genotype shed by California ground squirrels is not infectious for mice and may constitute a new species of Cryptosporidium.

California ground squirrels (Spermophilus beecheyi) are a ubiquitous species found in grasslands, meadow complexes, agricultural regions, and lower-elevation woodlands from central Washington state south to Baja California Norte in Mexico. In California, we have determined that this host species can shed relatively high concentrations of Cryptosporidium oocysts (5 × 104 oocysts g−1), with at least two genotypes circulating in this host species (4). Given that population densities can range from 8.4 to 92 adults ha−1 (6, 14, 15) and given the estimated mean fecal production of 12 g squirrel−1 day−1 (4), this ground-dwelling species can produce 9 × 105 to 1 × 107 oocysts ha−1 day−1 during summer and early fall (4). These findings suggest that endemic infection by Cryptosporidium spp. among colonies of California ground squirrels may promote the environmental cycling of Cryptosporidium spp. between wildlife and other susceptible host populations (13), collectively increasing the environmental loading rate of Cryptosporidium spp. on watersheds. We conducted the following study in order to better estimate the annual rate of environmental loading of Cryptosporidium spp. by colonies of California ground squirrels, to better map the distribution of genotypes for this host species, and to determine if the phenology of Cryptosporidium infection in California ground squirrels could help explain the epidemiologic observation that beef calves on California rangeland exhibit a spike in fecal shedding of Cryptosporidium parvum in May (2, 3).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection.

Six regions were selected from throughout Kern County, Calif., ranging from Sierra foothill oak woodlands dominated by blue oak (Quercus douglasii) and intermixed with interior live oak (Quercus wislizenii) and foothill pines (Pinus sabiniana) in the Tehachapi Mountains and the western slopes of the southern Sierra Nevada range to open grasslands dominated by annual species in the eastern foothills of the Temblor range. Within each region, squirrels were collected from three to six different sites during each month of the project, beginning in February 2000 and ending in February 2001. Squirrels were weighed, their sex was identified, and they were assigned to an age class (9). Fecal samples were collected from the lower section of the colon during necropsy.

Enumeration of Cryptosporidium.

Concentration of oocysts from sieved fecal suspensions and direct immunofluorescence microscopy were used to detect and enumerate Cryptosporidium oocysts, as previously described (4). Final oocyst counts were adjusted for percent recovery, determined previously to be ∼10% for oocyst concentrations of <1,000 g of feces−1 and ∼16.5% for oocyst concentrations of ≥1,000 g of feces−1 (4).

DNA extraction.

For selected isolates, oocysts were purified by using anti-Cryptosporidium Dynabeads (Dynal, Inc., Lake Success, N.Y.). DNA was extracted after five freeze (−80°C) and thaw (+80°C) cycles followed by overnight incubation at 60°C in TES [N-tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid] buffer containing 0.8% Sarkosyl (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). DNA was precipitated in 100% cold ethanol, dried, and stored at 4°C in Ultra Pure distilled water (DNase, RNase free; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, Calif.).

PCR and DNA sequencing.

PCR amplification of the 18S small-subunit (SSU) rRNA gene locus was performed according to the methodology described by Xiao et al. (18, 19), except that 3 mM MgCl2 was used for both primary and secondary PCR. After PCR amplification, the positive nested PCR fragment was sequenced in both directions (forward and reverse sequences) by using an ABI 3730 Capillary Electrophoresis Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). A positive control was obtained from an infected dairy calf from Pixley, Calif. A negative control was included by substituting sterile water for DNA.

Sequence analyses.

Multiple alignment of the DNA reverse and forward sequences was done with the Vector NTI Advance package from InforMax, Inc. (Frederick, Md.). The aligned sequence was compared to other sequences present in the GenBank database and to the sequence obtained from C. parvum isolated from a dairy calf in California.

Infectivity assay for neonatal BALB/c mice.

Cryptosporidium oocysts were purified from feces of heavily infected California ground squirrels by using a discontinuous sucrose gradient (1) and stored in deionized water at 4°C for no more than 14 days prior to use. Oocysts were observed with phase-contrast microscopy, and the concentration of intact oocysts was determined as the arithmetic mean of six separate counts with a hemacytometer, which was then adjusted to a concentration of 105 oocysts per ml of deionized water.

Individual litters of neonatal BALB/c mice and their dams were purchased from Harlan Company (San Diego, Calif.), housed in cages with air filters, and given food and water ad libitum. Litters of 4-day-old neonatal mice were given either 100, 5,000, or 10,000 oocysts in 100 μl of deionized water. Each pup was given oocysts from only one infected host, with no doses constructed by mixing oocysts isolated from separate infected California ground squirrels. Intragastric inoculations were done using a 24-gauge ball-point feeding needle. In addition, a litter of pups was used as a positive-control group which received an equivalent dose of freshly purified bovine C. parvum oocysts along with a litter of pups receiving only 100 μl of distilled water (negative control).

Cryptosporidium infections in neonatal mice were assessed by two methods: by staining homogenates of mouse intestinal tissue with a fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-Cryptosporidium immunoglobulin M antibody (Waterborne Inc., New Orleans, La.) and by histology performed by a board-certified veterinary pathologist. The first method was a minor modification of the method of Hou et al. (10), which was based in part on methods developed by Freire-Santos et al. (7), Mtambo et al. (12), and Vergara-Castiblanco et al. (17). Briefly, mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation 7 days after inoculation. The entire intestine was removed, suspended in 5 ml of deionized water, and homogenized with a KIKA-Werke instrument (IKA-Werke GmbH & Co. KG, Staufen, Germany). The tissue homogenates were washed in deionized water and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was removed. Pellets were resuspended in 10 ml of deionized water and filtered through a 20-μm-pore-size nylon net filter (Millipore Co., Bedford, Mass.) fixed on a Swinnex holder (Millipore). The filtrates were concentrated to 1 ml by centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 10 min. Fifty microliters of the final suspension was mixed with 50 μl of anti-Cryptosporidium monoclonal antibodies (Meridian, Cincinnati, Ohio) and 2 μl of 0.5% Evans blue in phosphate-buffered saline and incubated at room temperature for 45 min in a dark box. Three duplicate wet mount slides were prepared from each sample, by using 20 μl of reaction mixture per slide. Slides were examined at 400× with an epifluorescence microscope (BX 60; Olympus America Inc., Melville, N.Y.). For histopathology, 5-mm-thick portions of ileum, cecum, and colon were collected and immediately fixed in a 10% neutral-buffered formalin solution, processed by standard histopathology techniques, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 7 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (10). Histologic sections of ileum, cecum, and proximal colon were examined for C. parvum oocysts attached to enterocytes under light microscopy at ×100, ×200, and ×400. We have found previously that the method of using tissue homogenates coupled with direct immunofluorescence microscopy for determining the infection status of inoculated neonatal mice is twice as sensitive as histopathology (10).

Statistical analyses.

The prevalence of fecal shedding was compared between age, sex, and age-by-sex groupings, by using logistic regression, with trapping site set as a cluster variable (as explained in volume 2 of Stata Statistical Software: Release 7.0, Reference H-P, p. 221-247 [Stata Corporation, College Station, Tex.], 2001). The intensity of oocyst shedding (mean number of oocysts per gram of feces) was compared between these same age, sex, and age-by-sex groupings by using negative binomial regression, with trapping site set as a cluster variable (as explained in volume 2 of Stata Statistical Software: Release 7.0, Reference H-P, p. 383-392).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequences of the SSU rRNA gene of Cryptosporidium isolated from S. beecheyi have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers AY462231 to AY462233.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

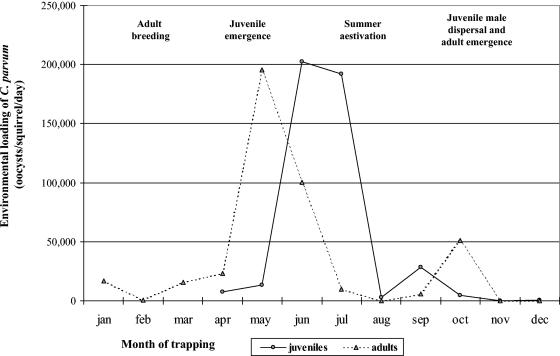

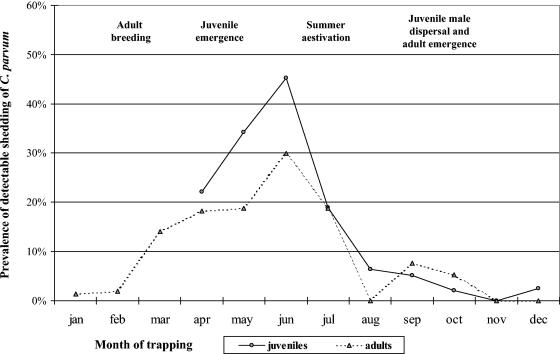

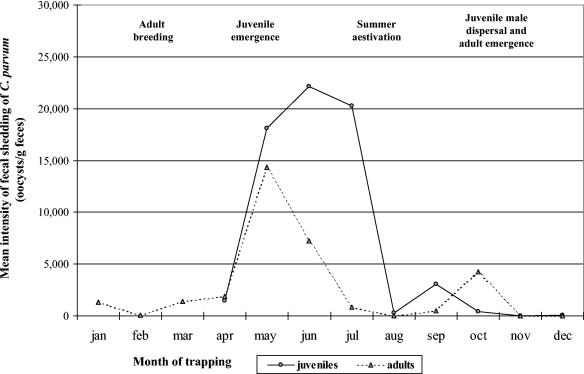

One hundred (12%) of 853 squirrels from six different geographic locations had detectable concentrations of Cryptosporidium oocysts (Table 1). The arithmetic mean intensity of fecal shedding of Cryptosporidium for the 100 positive squirrels was 44,482 oocysts g of feces−1, which ranged from 540 to 543,364 oocysts g of feces−1 (first quartile, 4,324 oocysts g−1; third quartile, 55,000 oocysts g−1, median, 14,324 oocysts g−1). If all 853 squirrels were averaged across the study, the overall arithmetic mean was 5,209 oocysts g of feces−1. The arithmetic mean body weight of all squirrels in the study was 555.6 g. It was determined previously that daily fecal production (wet weight) by California ground squirrels is ∼2% body weight (4). Therefore, the environmental loading rate of Cryptosporidium oocysts from this host species, when averaged across the 12 months, was 57,882 oocysts squirrel−1 day−1 (555.6 g squirrel−1 × 0.02 fecal mass day−1 × 5,209 oocysts g of feces−1), but these values vary dramatically depending on season (see Fig. 3). These values are similar to the overall mean intensities of 8,543 oocysts g of feces−1 and 93,973 oocysts squirrel−1 day−1 that were observed previously for California ground squirrels tested during June through October (4). Compared to adult squirrels, juveniles had on average a twofold-higher prevalence of infection and a two- to fourfold-higher intensity of fecal shedding (Table 1). The low to moderate prevalences of infection (7 to 18%, data not shown) among dams during pregnancy and pupping likely function to infect a subset of newborn squirrels prior to emergence from natal burrows, resulting in the observed 22 to 34% prevalence of infection among juveniles in April and May (Fig. 1). As juvenile emergence is completed in May (6, 8, 9, 14), a rapid expansion of Cryptosporidium infection occurs among both juvenile and adult squirrels during the summer months (two-sided P < 0.05), evidenced by the sharp increase in both the prevalence and the intensity of fecal shedding of Cryptosporidium during June and July. Following this summer peak of Cryptosporidium infection, colonies of ground squirrels appeared to develop immunity to this parasite, resulting in sharp declines of fecal shedding of oocysts during August, with these low infection indices then lasting through the subsequent winter months (Fig. 1 and 2).

TABLE 1.

Prevalence and intensity of shedding of C. parvum oocysts by California ground squirrels (S. beecheyi)d

| Stratification | No. of squirrels (%)a | Mean no. of oocysts/g (SD)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Positiveb | Totalc | ||

| Age | |||

| Juvenile | 63/418 (15)A | 55,034A (84,021) | 8,295A (37,924) |

| Adult | 37/435 (8.5)B | 26,515B (54,798) | 2,255B (17,433) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 52/474 (11) | 50,657 (92,726) | 5,557 (34,325) |

| Female | 48/379 (13) | 37,792 (50,973) | 4,786 (21,942) |

| Age and sex | |||

| Male juvenile | 34/227 (15)A | 58,477A (101,624) | 8,759A (44,107) |

| Male adult | 18/247 (7.3)B | 35,885A,B (73,441) | 2,615B (21,450) |

| Female juvenile | 29/191 (15)A | 50,997A (58,557) | 7,743A (29,017) |

| Female adult | 19/188 (10)A,B | 17,638B (27,216) | 1,783B (9,986) |

| Overall | 100/853 (12) | 44,482 (75,528) | 5,209 (29,443) |

Number positive/number sampled.

Arithmetic mean (standard deviation) for the number of oocysts shed per gram for positive fecal samples from the specified population, adjusted for percent recovery of direct immunofluorescence microscopy.

Arithmetic mean (standard deviation) for the number of oocysts shed per gram in all fecal samples collected from the specified population, adjusted for percent recovery of direct immunofluorescence microscopy.

Values with different capital-letter superscripts within the same demographic group are significantly different at the 0.10 level.

FIG. 3.

Environmental loading of C. parvum by California ground squirrels (S. beecheyi), stratified by month and age class.

FIG. 1.

Prevalence of C. parvum infection in California ground squirrels (S. beecheyi), stratified by month and age class.

FIG. 2.

Intensity of fecal shedding of C. parvum oocysts in California ground squirrels (S. beecheyi), stratified by month and age class.

The seasonal shifts in population structure for California ground squirrel colonies (6, 8, 9, 14) in combination with the seasonal shifts in the prevalence and intensity of oocyst shedding (Fig. 1 and 2) result in significant fluctuations (two-sided P < 0.05) in the environmental loading rate across the year for this host species (Fig. 3). Prior to emergence of juvenile squirrels in April, the monthly environmental loading rate for adults averaged 740 to 16,600 oocysts squirrel−1 day−1. During and following juvenile emergence, the monthly environmental loading rate for adults increased rapidly to 196,000 oocysts squirrel−1 day−1 in May, with juveniles reaching a peak 1 to 2 months later at ∼200,000 oocysts squirrel−1 day−1. Loading rates declined substantially for the remainder of the year. Based on these average monthly values, approximately 71% of oocysts produced by the adult members of a ground squirrel colony during a 12-month period were produced during just May and June, with 47% produced in May alone (Fig. 3). Similarly, 87% of the cumulative annual oocyst production by juvenile members of the colony occurred in just June and July.

A primary mechanism of transporting large numbers of Cryptosporidium oocysts from the terrestrial to the aquatic component of a watershed is when high rates of environmental loading of Cryptosporidium occur in conjunction with overland flow conditions (e.g., rates of precipitation exceeding infiltration) (5, 11, 16). Throughout much of the geographical range of S. beecheyi, overland flow conditions typically occur between November and March, months in which this host species has a reduced rate of Cryptosporidium loading relative to that for May through July (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, Cryptosporidium loading rates in, for example, January are on average 16,593 oocysts squirrel−1 day−1 (629 g squirrel−1 × 0.02 fecal mass day−1 × 1,319 oocysts g of feces−1). Assuming that squirrel population densities are at the lower end of the reported range of 8.4 to 92 adults ha−1 (6, 9, 14), for example, 20 squirrels ha−1 for a 5,000-ha watershed, then daily Cryptosporidium loading from this host species alone would be 1.7 × 109 oocysts day−1.

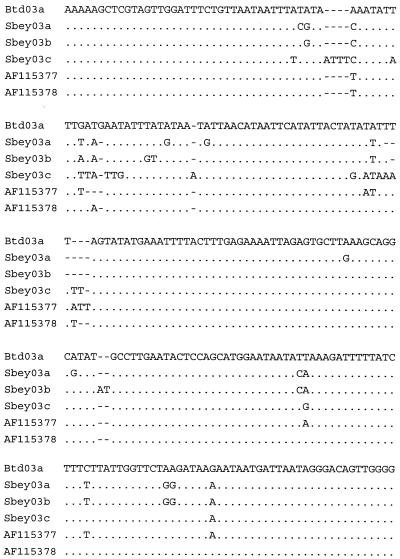

Based on DNA sequencing of a portion of the 18S SSU rRNA gene, we isolated up to three potentially different genotypes of Cryptosporidium in this population of squirrels (Sbey03a, Sbey03b, and Sbey03c), with 82% of the isolates (9 of 11) being Sbey03c (Fig. 4) from squirrels located in the Temblor range, the Tehachapi Mountains, and the southern Sierra Nevada (30- to 80-mile distances between trap locations). These different genotypes were isolated from different squirrels, with no squirrel found to be shedding more than one genotype. The DNA sequences did not perfectly match any existing Cryptosporidium DNA sequences that have been deposited in the GenBank database as of 20 May 2004. These unique DNA sequences were slightly more closely related (96 to 97% homology) to porcine C. parvum (AF115377) and C. wrairi (AF115378) than to bovine genotype A C. parvum (95 to 96% homology). Furthermore, Cryptosporidium genotype Sbey03c shared slightly more DNA sequence homology to porcine C. parvum (96%) and C. wrairi (96%) than to Cryptosporidium Sbey03a and Sbey03b (95%) from the same host species, but these relationships need to be substantiated with additional DNA sequence information from other Cryptosporidium genes before firm conclusions can be made. Interestingly, had one used the more popular PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) genotyping method, which also targets the 18S SSU rRNA gene (18, 19), a researcher may have misclassified Sbey03a, Sbey03b, or Sbey03c as a common porcine genotype, depending on the individual's skill at distinguishing a 454-bp band from a 446-bp band (Table 2). Interestingly, in a previous project on Cryptosporidium genotypes in California ground squirrels, a porcine PCR-RFLP pattern was identified using this nested PCR-RFLP method (4), which suggests that this popular method of genotyping can incorrectly lump together distinct isolates of Cryptosporidium into broader genotype categories, leading to false epidemiologic linkages.

FIG. 4.

Polymorphic region of the 18S SSU rRNA gene demonstrating three genotypes of Cryptosporidium (Sbey03a, Sbey03b, and Sbey03c) isolated from California ground squirrels (S. beecheyi), compared to C. parvum bovine genotype A (California dairy calf isolate Btd03a), C. parvum porcine genotype I (AF115377), and C. wrairi (AF115378). A period signifies that the base is identical to that of the bovine genotype A reference; a dash signifies a base deletion with respect to the bovine genotype A reference.

TABLE 2.

Predicted PCR-RFLP genotype patterns targeting the 18S SSU rRNA gene (18) for novel C. parvum isolates from California ground squirrels (S. beecheyi) compared to existing bovine and porcine genotypes

| Genotypea | Size of amplicon (bp) | SspI digestion | VspI digestion |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGS-A (Sbey03a) | 786b | 11, 11, 346,b 418b | 76,b 104, 606b |

| CGS-B (Sbey03b) | 838 | 11, 11, 362, 454 | 102, 104, 632 |

| CGS-C (Sbey03c) | 822 | 12, 364, 446 | 102, 104, 616 |

| Pig-Ic | 838 | 9, 11, 365, 453 | 102, 104, 632 |

| Bovine-Ad | 834 | 11, 12, 108, 254, 449 | 102, 104, 628 |

CGS, California ground squirrel.

Amplicon had over 800 bp, but reliable DNA sequence information was limited to 786 bp, leading to artificial shortening of the indicated PCR-RFLP fragements.

Porcine isolate from GenBank, accession no. AF115377.

Bovine isolate (Btd03a) from a California dairy calf born in 2003, characterized as bovine genotype A, as defined in the work of Xiao et al. (18).

Inoculating litters of BALB/c neonatal mice with up to 10,000 oocysts from two different isolations of Sbey03b (different squirrel hosts) and two different isolations of Sbey03c (different squirrel hosts) did not produce detectable levels of infection, suggesting that these genotypes shed by California ground squirrels are not infectious for mice and possibly represent a new species of Cryptosporidium. Due to Sbey03a being the rarest of genotypes in this sample, we have been unable to obtain sufficient numbers of oocysts to conduct a mouse infectivity trial.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted in part under the auspices of the Bernice Barbour Communicable Disease Laboratory, with financial support from the Bernice Barbour Foundation, Hackensack, N.J., as a grant to the Center of Equine Health, University of California, Davis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arrowood, M. J., and C. R. Sterling. 1987. Isolation of Cryptosporidium oocysts and sporozoites using discontinuous sucrose and isopycnic Percoll gradients. J. Parasitol. 73:314-319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atwill, E. R., E. Johnson, D. J. Klingborg, G. M. Veserat, G. Markegard, W. A. Jensen, D. W. Pratt, R. E. Delmas, H. A. George, L. C. Forero, R. L. Phillips, S. J. Barry, N. K. McDougald, R. R. Gildersleeve, and W. E. Frost. 1998. Age, geographic, and temporal distribution of fecal shedding of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts in cow-calf herds. Am. J. Vet. Res. 60:420-425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atwill, E. R., E. Johnson, and M. Das Graças C. Pereira. 1999. Herd composition, stocking rate, and calving duration associated with fecal shedding of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts in beef cattle herds. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 215:1833-1838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atwill, E. R., S. Maldonado Camargo, R. Phillips, L. H. Alonso, K. W. Tate, W. A. Jensen, J. Bennet, S. Little, and T. P. Salmon. 2001. Quantitative shedding of two genotypes of Cryptosporidium parvum in California ground squirrels (Spermophilus beecheyi). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2840-2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atwill, E. R., L. Hou, B. M. Karle, T. Harter, K. W. Tate, and R. A. Dahlgren. 2002. Transport of Cryptosporidium parvum through vegetated buffer strips and estimated filtration efficiency. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5517-5527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boellstorff, D. E., and D. H. Owings. 1995. Home range, population structure, and spatial organization of California ground squirrels. J. Mammal. 76:551-561. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freire-Santos, F., A. M. Oteiza-Lopez, C. A. Vergara-Castiblanco, and M. E. Ares-Mazas. 1999. Effect of salinity, temperature and storage time on mouse experimental infection by Cryptosporidium parvum. Vet. Parasitol. 87:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holekamp, K. E. 1984. Dispersal in ground-dwelling sciurids, p. 297-320. In J. O. Murie and G. R. Michener (ed.), The biology of ground-dwelling squirrels. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln.

- 9.Holekamp, K. E., and S. Nunes. 1989. Seasonal variation in body weight, fat, and behavior of California ground squirrels (Spermophilus beecheyi). Can. J. Zool. 67:1425-1433. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hou, L., X. Li, L. Dunbar, R. Moeller, B. Palermo, and E. R. Atwill. 2004. Neonatal-mouse infectivity of intact Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts isolated after optimized in vitro excystation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:642-646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mawdsley, J. L., A. E. Brooks, R. J. Merry, and B. F. Pain. 1996. Use of a novel tilting table apparatus to demonstrate the horizontal and vertical movement of the protozoan Cryptosporidium parvum in soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 23:215-220. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mtambo, M. M., E. Wright, A. S. Nash, and D. A. Blewett. 1996. Infectivity of a Cryptosporidium species isolated from a domestic cat (Felis domestica) in lambs and mice. Res. Vet. Sci. 60:61-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okhuysen, P. C., C. L. Chappell, J. H. Crabb, C. R. Sterling, and H. L. DuPont. 1999. Virulence of three different Cryptosporidium parvum isolates for healthy adults. J. Infect. Dis. 180:1275-1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owings, D. H., M. Borchert, and R. Virginia. 1977. The behaviour of California ground squirrels. Anim. Behav. 25:221-230. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schitoskey, F., Jr., and S. R. Woodmansee. 1978. Energy requirements and diet of the California ground squirrel. J. Wildl. Manag. 42:373-382. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tate, K. W., E. R. Atwill, M. R. George, N. K. McDougald, and R. E. Larsen. 2000. Cryptosporidium parvum mobilization and transport from livestock fecal deposits on California rangeland watersheds. J. Range Manag. 53:295-299. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vergara-Castiblanco, C. A., F. Freire-Santos, A. M. Oteiza-Lopez, and M. E. Ares-Mazas. 2000. Viability and infectivity of two Cryptosporidium parvum bovine isolates from different geographical location. Vet. Parasitol. 89:261-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao, L., L. Escalante, C. Yang, I. Sulaiman, A. A. Escalante, R. J. Montali, R. Fayer, and A. A. Lal. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis of Cryptosporidium parasites based on the small-subunit rRNA gene locus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1578-1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao, L., K. Alderisio, J. Limor, M. Royer, and A. A. Lal. 2000. Identification of species and sources of Cryptosporidium oocysts in storm waters with a small-subunit rRNA-based diagnostic and genotyping tool. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5492-5498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]