Abstract

Three Porphyromonas species (Porphyromonas asaccharolytica, P. endodontalis, and the novel species that is the subject of the present report, P. uenonis) are very much alike in terms of biochemical characteristics, such as enzyme profiles and cellular fatty acid contents. P. asaccharolytica is distinguished from the other two species by virtue of production of α-fucosidase and glyoxylic acid positivity. The novel species is difficult to differentiate from P. endodontalis phenotypically and was designated a P. endodontalis-like organism for some time. However, P. endodontalis is recovered almost exclusively from oral sources and also grows poorly on Biolog Universal Agar, both characteristics that are in contrast to those of the other two organisms. Furthermore, P. uenonis is glycerol positive in the Biolog AN Microplate system. Both P. asaccharolytica and P. uenonis are positive by 13 other tests in the Biolog system, whereas P. endodontalis is negative by all of these tests. P. asaccharolytica grew well in both solid and liquid media without supplementation with 5% horse serum, whereas the other two species grew poorly without supplementation. Sequencing of 16S rRNA revealed about 10% divergence between the novel species and P. endodontalis but less than 2% sequence difference between the novel species and P. asaccharolytica. Subsequent DNA-DNA hybridization studies documented that the novel organism was indeed distinct from P. asaccharolytica. We propose the name Porphyromonas uenonis for the novel species. We have recovered P. uenonis from four clinical infections in adults, all likely of intestinal origin, and from the feces of six children.

Porphyromonas endodontalis has been recovered almost exclusively from oral sources (12), whereas a novel organism that we encountered and originally called the P. endodontalis-like organism appears to be found primarily in sources indicating an intestinal origin. The novel organism, P. uenonis, is phenotypically similar to P. endodontalis and P. asaccharolytica. The aim of this study was to describe the isolation and characterization of this novel organism, which is a species distinct from the other two species, and to describe tests useful in distinguishing between these three organisms. We also describe the types of infections in which we have found the novel species and its recovery from the feces of children.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Six isolates of the novel species obtained from fecal specimens of young children in Helsinki, Finland, were included in the bacteriologic and genetic studies: four strains recovered from clinical infections (one each of appendicitis, peritonitis, pilonidal abscess, and an infected sacral decubitus ulcer; the four strains were from the Wadsworth Anaerobe Laboratory [WAL] collection), the ATCC 35406 strain of P. endodontalis (isolated from an infected root canal), and the ATCC 25260 strain of P. asaccharolytica (isolated from empyema fluid). Five additional P. endodontalis clinical isolates, all from oral sources, and five P. asaccharolytica clinical isolates, all from nonoral sources, were included in cellular fatty acid analyses.

The fecal strains were isolated during a microbiological study of antimicrobial agent-associated flora changes. The fecal samples were inoculated on various selective and nonselective media by quantitative culture techniques (6). For the isolation of the novel organism, brucella blood agar and kanamycin-vancomycin laked blood agar (KVLB) and phenylethyl alcohol blood agar (PEA) plates were incubated anaerobically for up to 10 days and were then examined; all but one strain grew within 7 days. The clinical WAL strains were characterized as part of a comprehensive reevaluation of pigmented gram-negative rods; they generally grew within 3 days.

Identification by conventional methods.

The strains were characterized by routine biochemical tests (5, 6) by using prereduced anaerobically sterilized biochemicals, gas-liquid chromatography for metabolic end products (6), API ZYM panels (BioMerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France), the RapID ANA II system (Remel, Lenexa, Kans.), the AN Microplate system (Biolog, Hayward, Calif.), and Rosco (Taastrup, Denmark) diagnostic tablets. The production of β-lactamase was detected by the nitrocefin disk test (Biodisk). Antimicrobial susceptibility studies were done with three strains and various antimicrobial agents by the NCCLS-approved Wadsworth agar dilution method (8).

Cellular fatty acid analysis.

Cellular fatty acids were detected with a Hewlett-Packard 5890 series II gas chromatograph and Microbial Identification System software (MIDI, Newark, N.J.). The isolates were grown on supplemented brain heart infusion agar with blood, and the bacterial mass was harvested directly from the plates because of poor growth in liquid medium. The corresponding library (ANAEROBE, version Moore 5.0) was used in successive analyses.

Genotypic characterization.

The mole percent G+C contents of the organism DNAs were determined by high-pressure liquid chromatography (7). The 16S rRNA genes were amplified by PCR, and the products were sequenced directly with a Biotech Diagnostic (Laguna Niguel, Calif.) Big Dye sequencing kit on an ABI 377 sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The sequences obtained were compared with the sequences in the GenBank database by using BLAST software (1), and the percent similarity to other sequences was determined. Closely related sequences were retrieved from GenBank and were aligned with the newly determined sequences by using the program DNA Tools (10). The resulting multiple-sequence alignment (with approximately 100 bases at the 5′ end of the molecule omitted from further analysis because of alignment uncertainties due to highly variable region V1) was analyzed with the program GeneDoc (9). DNA-DNA reassociation experiments were done by the spectrophotometric method of De Ley et al. (2) with a Gilford system model 2600 spectrophotometer equipped with a Gilford model 2527-R thermal programmer.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank accession number for P. uenonis is AY570514.

RESULTS

The novel species recovered from clinical infections were always isolated together with other anaerobes or aerobes. The mean number of accompanying anaerobes was 4.7, and the mean number of accompanying aerobes was 1.8.

The novel species was detected in fecal specimens of 6 of 30 children. It was isolated only from the area of heavy growth on brucella blood agar, KVLB, or PEA plates and not as single colonies. In the initial cultures, an incubation time of at least 7 days was required before the pigmentation of the novel species, which assisted in its recognition, was detected. On subculture, growth and colony pigmentation occurred in 3 days on laked rabbit blood agar. The counts of the novel species in the fecal samples were low (<103 CFU/g).

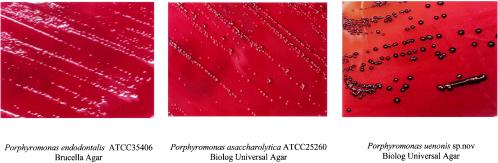

All isolates of the novel species were sensitive to the vancomycin special-potency disk, and all except one isolate were resistant to the kanamycin and colistin special-potency disks; the one isolate that was the exception was sensitive to colistin. Colonies produced a black pigment (Fig. 1) after 3 days of incubation on laked rabbit blood agar and exhibited red fluorescence under UV light (366 nm) earlier than that. There was weak beta-hemolysis on blood agar plates. Both the novel species and P. asaccharolytica grew better on Biolog Universal Agar (BUA) than on brucella blood agar; P. endodontalis grew poorly on BUA. P. uenonis strains were indole positive; were lipase, catalase, and nitrate negative; were inhibited by bile; were asaccharolytic; and produced acetic, propionic, isobutyric, butyric, isovaleric, and succinic acids as metabolic end products. The API ZYM kit gave positive reactions for alkaline phosphatase, esterase, esterase lipase, acid phosphatase, and naphthol-AS-BI phosphohydrolase and variable reactions for leucine arylamidase. The organism was negative for α-fucosidase, the enzyme that distinguishes P. asaccharolytica from P. endodontalis, both by the API ZYM test and with Rosco diagnostic tablets. None of the tests applied by the RapID ANA II system except for the aforementioned α-fucosidase test reliably distinguished between the three species under consideration. The codes generated by the RapID ANA II system differed only by the α-fucosidase test. The Biolog AN Microplate 95 test card, which was used to test four wild strains of P. uenonis and the type strains of all three species, also consistently showed a positive α-fucosidase test result only for P. asaccharolytica; but, in addition, it showed that P. asaccharolytica was the only one of the three species positive for glyoxylic acid, and among the three species, only P. uenonis was positive for glycerol. Both P. asaccharolytica and P. uenonis tested positive and P. endodontalis tested negative by a number of other tests: d-cellobiose, dextrin, d-galacturonic acid, gentibiose, α-d-glucose, glucose-6-phosphate, maltose, d-mannose, 3-methyl-d-glucose, β-methyl-d-glucose, d-trehalose, turanose, and α-ketobutyric acid (despite the designation “asaccharolytica” for P. asaccharolytica). Antimicrobial susceptibility tests, usually one strain per drug, revealed that the novel species was highly susceptible (MIC, <1 μg/ml) to amoxicillin-clavulanate, piperacillin-tazobactam, ticarcillin-clavulanate, imipenem, meropenem, ceftizoxime, clindamycin, trovafloxacin, gemifloxacin, and metronidazole. Two isolates produced β-lactamases, and their susceptibilities to penicillin G and ampicillin were variable. The ciprofloxacin MIC for one strain was 2 μg/ml. One strain was highly resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Testing with prereduced anaerobically sterilized biochemicals was not helpful in distinguishing the three species.

FIG. 1.

Colonial appearance on blood agar plates after 7 days of incubation. P. endodontalis grew poorly on BUA. Note the differences in the degrees of pigmentation.

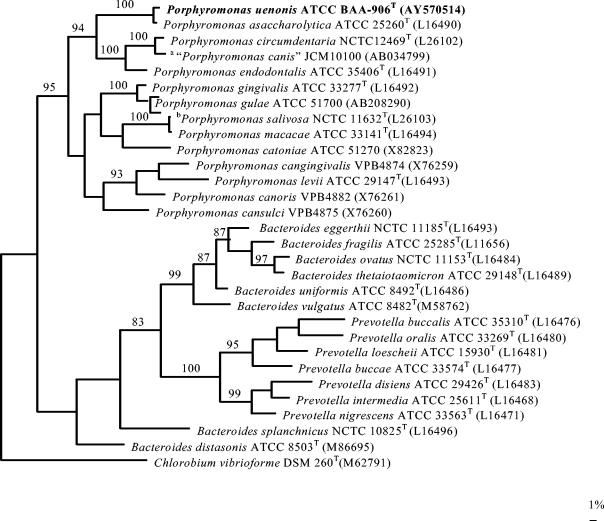

The main cellular fatty acid detected in the novel species was iso-C15:0 (50 to 60% of the total fatty acids); the four other cellular fatty acids were found only in amounts that ranged from 2.17 to 9.4% of the total acids. A cellular fatty acid found in cytophaga-flavobacter-bacteroides-type bacteria, 3OHi17:0, was not found in any of our isolates. The patterns were not reliable for identification of any of the three species, nor were they reliable for distinguishing between them, perhaps due to a limited database for these organisms. Table 1 lists useful characteristics for the identification of P. endodontalis, P. asaccharolytica, and the novel species (P. uenonis). The G+C content of the proposed type strain (designated strain WAL 9902, ATCC BAA-906, or CCUG 48615) of the novel species is 52.5 mol%; this is within the parameters described for the genus Porphyromonas (range, 46 to 54 mol%) (11). The strains of the novel species were genetically highly related to each other (>99% sequence similarity). Comparison of the sequence similarities of the novel species and P. endodontalis showed that they are distant from each other (89.5% sequence similarity), but comparison of the novel species and P. asaccharolytica showed that they are quite closely related (98.2 to 98.9% sequence similarity). The latter sequence similarity would be consistent with the two species belonging to the same species; however, a DNA-DNA reassociation study between the proposed type strain (WAL 9902) of the novel species (P. uenonis) and the type strain of P. asaccharolytica (ATCC 25260) showed that the similarity was only 54.3% (59.9% on repeat analysis), documenting that they are distinct species. A phylogenetic tree is shown in Fig. 2.

TABLE 1.

Differential characteristics of selected Porphyromonas speciesa

| Species | Reactionb

|

Source | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Fuc | β-NAG | Glyoxylic acid | Glycerol | Serum stim. | BUA | ||

| P. asaccharolytica | + | − | + | − | − | Good | Nonoralc |

| P. endodontalis | − | − | − | − | + | Poor | Oralc |

| P. uenonis | − | ± | − | + | + | Good | Nonoralc |

Symbols and abbreviations: +, positive reaction; −, negative reaction; ±, sometimes positive and sometimes negative reaction; α-Fuc, α-fucosidase activity; β-NAG, N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase activity; Serum stim., growth stimulated by serum; BUA, growth on BUA; source, likely source as indigenous flora.

Occasional exceptions were noted.

FIG. 2.

Unrooted tree showing the phylogenetic position of P. uenonis sp. nov. within the Bacteroides subgroup of the cytophaga-flavobacter-bacteroides phylum. The tree was constructed by the maximum-parsimony method and is based on a comparison of approximately 1,400 nucleotides. Bootstrap values, expressed as a percentage of 1,000 replications, are given at the branching points. The scale bar indicates 1% sequence divergence. Superscript letters: a, “Porphyromonas canis” is not a valid species; Superscript letters: b, Porphyromonas salivosa is a junior synonym of Porphyromonas macacae (6a). Although P. crevioricanis and P. gingicanis are valid species (4), their 16S rRNA gene sequences are not available in public databases; therefore, they are not included in the phylogenetic tree.

DISCUSSION

The isolation and identification of P. endodontalis and the novel species, P. uenonis, are difficult. These organisms are highly sensitive to oxygen, grow slowly and poorly without supplementation (e.g., with horse serum), and produce pigment in the initial cultures sometimes only after 7 days or more of incubation. Furthermore, biochemically they are very inert, except in the Biolog AN Microplate system. The isolation of fecal strains of P. uenonis was difficult because of their presence in very small numbers; the colonies could not be detected before pigmentation became visible. P. endodontalis is recovered almost exclusively from oral sources. P. asaccharolytica, in contrast to the two previously mentioned organisms, grows well on both plated media and liquid media without horse serum supplementation. It is otherwise identical to the other two organisms by phenotypic tests, except that it is α-fucosidase positive (3) and glyoxylic acid positive. Sequencing of 16S rRNA readily distinguishes between P. endodontalis and P. uenonis, but DNA-DNA reassociation studies are required to distinguish genetically between P. asaccharolytica and P. uenonis.

The novel species described here, P. uenonis, appears to be of relatively low virulence since it was always found in mixed culture and was not recovered in blood cultures or from patients with serious infections. It is also quite susceptible to most antimicrobial agents, although β-lactamase production was noted in some strains. More data on the range and types of infections that this organism causes and its antimicrobial susceptibility are needed.

Description of P. uenonis sp. nov.

Porphyromonas uenonis (uenonis, to honor the Japanese microbiologist Kazue Ueno, who has contributed so much to our knowledge of gram-negative anaerobic rods and anaerobic bacteriology in general) cells are gram-negative rods. The organism is obligately anaerobic. Growth is stimulated by 5% horse serum and similar additives. Black pigment occurs in colonies on blood-containing agar media after 7 or more days of incubation for primary isolation and after 3 days on laked rabbit blood agar for subsequent subculture. Weak beta-hemolysis is noted on brucella blood agar. Colonies exhibit red fluorescence under long-wave UV light, especially before pigment has developed. The organism is asaccharolytic except in the Biolog AN Microplate system; the metabolic end products found by gas-liquid chromatography are acetic, propionic, isobutyric, butyric, isovaleric, and succinic acids. The organism is indole positive; is lipase, catalase, and nitrate negative; and is inhibited by bile. Positive reactions for alkaline phosphatase, esterase, esterase lipase, acid phosphatase, and naphthol-AS-BI phosphohydrolase are detected; and variable reactions for leucine arylamidase are detected. The organism is negative for α-fucosidase. The principal cellular fatty acid is iso-C15:0. Some strains produce β-lactamase. The organism is susceptible to most antimicrobial agents. It is found as part of a mixed flora in various infections, which apparently have their origin in the intestinal tract. The organism's habitat is probably the human gut. The type strains are WAL 9902, ATCC BAA-906, and CCUG 48615. The G+C content of the type strain is 52.5 mol%.

Acknowledgments

This work has been carried out, in part, with financial support from Veterans Affairs Merit Review research funds.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benson, D. A., M. S. Boguski, D. J. Lipman, and J. Ostell. 1997. Gen-Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Ley, J., H. Cattoir, and A. Reynaerts. 1970. The quantitative measurements of DNA hybridization from renaturation rates. Eur. J. Biochem. 12:133-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durmaz, B., H. R. Jousimies-Somer, and S. M. Finegold. 1995. Enzymatic profiles of Prevotella, Porphyromonas, and Bacteroides species obtained with the API ZYM system and Rosco Diagnostic Tablets. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20(Suppl. 2):S192-S194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirasawa, M., and K. Takada. 1994. Porphyromonas gingivicanis sp. nov. and Porphyromonas crevioricanis sp. nov., isolated from beagles. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44:637-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jousimies-Somer, H. R. 1995. Update on the clinical and laboratory characteristics of pigmented anaerobic gram-negative rods. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20(Suppl. 2):S187-S191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jousimies-Somer, H. R., P. Summanen, D. M. Citron, E. J. Baron, H. M. Wexler, and S. M. Finegold. 2002. Wadsworth anaerobic bacteriology manual. Star Publishing Company, Belmont, Calif.

- 6a.Love, D. N. 1995. Porphyromonas macacae comb. nov., a consequence of Bacteroides macacae being a senior synonym of Porphyromonas salivosa. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:90-92. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mesbah, M., U. Premachandran, and W. B. Whitman. 1989. Precise measurement of the G+C content of deoxyribonucleic acid by high performance liquid chromatography. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 39:159-167. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2001. Methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of anaerobic bacteria, 5th ed. Approved standard. NCCLS document M11-A5, National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 9.Nicholas, K. B., H. B. Nicholas, Jr., and D. W. Deerfield II. 1997. GeneDoc: analysis and visualization of genetic variation. EMBNEW News 4:14. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasmussen, S. W. 1995. DNATools: a software package for DNA sequence analysis. Carlsberg Laboratory, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- 11.Shah, H. N., and M. D. Collins. 1988. Proposal for reclassification of Bacteroides asacchorolyticus, Bacteroides gingivalis, and Bacteroides endodontalis in a new genus, Porphyromonas. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 38:128-131. [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Winkelhoff, A. J., T. J. M. van Steenbergen, N. Kippuw, and J. de Graaf. 1985. Further characterization of Bacteroides endodontalis, an asaccharolytic black-pigmented Bacteroides species from the oral cavity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 22:75-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]