Abstract

Fusarium oxysporum is a phylogenetically diverse monophyletic complex of filamentous ascomycetous fungi that are responsible for localized and disseminated life-threatening opportunistic infections in immunocompetent and severely neutropenic patients, respectively. Although members of this complex were isolated from patients during a pseudoepidemic in San Antonio, Tex., and from patients and the water system in a Houston, Tex., hospital during the 1990s, little is known about their genetic relatedness and population structure. This study was conducted to investigate the global genetic diversity and population biology of a comprehensive set of clinically important members of the F. oxysporum complex, focusing on the 33 isolates from patients at the San Antonio hospital and on strains isolated in the United States from the water systems of geographically distant hospitals in Texas, Maryland, and Washington, which were suspected as reservoirs of nosocomial fusariosis. In all, 18 environmental isolates and 88 isolates from patients spanning four continents were genotyped. The major finding of this study, based on concordant results from phylogenetic analyses of multilocus DNA sequence data and amplified fragment length polymorphisms, is that a recently dispersed, geographically widespread clonal lineage is responsible for over 70% of all clinical isolates investigated, including all of those associated with the pseudoepidemic in San Antonio. Moreover, strains of the clonal lineage recovered from patients were conclusively shown to genetically match those isolated from the hospital water systems of three U.S. hospitals, providing support for the hypothesis that hospitals may serve as a reservoir for nosocomial fusarial infections.

Members of the phylogenetically diverse monophyletic Fusarium oxysporum complex (FOC) are best known as cosmopolitan soilborne plant pathogens that are responsible for economically devastating vascular wilts of an enormous range of agronomically important plant hosts (6). Members of the FOC are also frequently isolated from nonplant sources, particularly from the soil but also from air and animals. Over the past 2 decades, however, fusaria have emerged as opportunistic pathogens causing life-threatening disseminated infections in immunocompromised patients (3). In patients who are persistently neutropenic, deeply invasive fusarial infections cause 100% mortality (18). Most localized and disseminated cases of fusariosis are caused by members of the Fusarium solani species complex, followed by members of the FOC (1). Fortunately, the recent development of one strain of F. oxysporum as a model system will greatly facilitate the molecular genetic dissection of fungal virulence determinants during plant and animal pathogenesis (24).

Although molecular epidemiological studies have been completed for nosocomial fusariosis (1, 25), most of the analyses were conducted on members of the F. solani species complex. Nevertheless, a relationship between an environmental isolate and a patient isolate was determined in one case of infection due to a member of the FOC (1). Little is known about the molecular epidemiology of clinically important members of the FOC, even though they were isolated from a San Antonio, Tex., hospital pseudoepidemic (i.e., a false epidemic due to contamination of clinical specimens) associated with bronchoscopy specimens in 1997 to 1998 (S. E. Sanche, D. A. Sutton, K. Magnon, R. Cox, S. Revankar, and M. G. Rinaldi, Abstr. 98th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. F-102, 1998) (hereafter referred to as Texas hospital A) and as part of a 1996 environmental survey of a Houston, Tex., hospital water system suspected of serving as a reservoir of nosocomial fusariosis (1, 14) (hereafter referred to as Texas hospital B). Phylogenetic analyses of the FOC have been limited to phytopathogens (2, 21, 26). Results of these genetic diversity studies using multilocus DNA sequence typing (MLST) and amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLPs) have shown that some plant host-specific pathogens, called formae speciales, have polyphyletic evolutionary origins (2, 21, 26) and that this complex appears to consist of a large number of predominately or exclusively clonal lineages distributed among at least three clades. The latter finding was not unexpected, because no member of the FOC has been shown to undergo sexual reproduction, even though the few strains tested were shown to possess apparently functional mating-type (MAT) genes that are expressed and processed correctly (38).

The objectives of this study were to (i) investigate the genetic relatedness and population structure of a comprehensive set of isolates of the FOC from patients and the hospital environment spanning four continents, focusing on those recovered from the Texas hospital A pseudoepidemic; (ii) evaluate the hypothesis that hospital water systems might serve as reservoirs for nosocomial fusariosis by comparing FOC strains recovered from the environment in hospitals in Texas (14), Maryland, and Washington with isolates derived from patients; and (iii) investigate the phylogenetic diversity and evolutionary origins of human- and hospital environment-derived isolates by comparing them with phytopathogenic strains chosen to represent the known pathogenic and phylogenetic diversity of the FOC. To achieve these objectives, we have developed an initial set of MLST- and AFLP-based molecular markers that can be incorporated into long-range epidemiological studies. Results of the MLST and AFLP analyses reported here provide independent support for the validity of a clinically important, widespread clonal lineage within the F. oxysporum complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains.

Isolates of the F. oxysporum species complex (FOC) from patients, the environment, and other plant and animal sources were assembled from several national and international culture collections, with most of the isolates supplied by The University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, Tex. (Table 1). All strains are stored cryogenically in the Agricultural Research Service (NRRL) Culture Collection, National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, Peoria, Ill., for future reference.

TABLE 1.

Strains of the F. oxysporum complex and outgroups included in this study

| NRRL no. | Other designationa | Yr | Isolate sourceb | Geographic origin | Hospital or laboratory data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22533 | CBS 244.61 | 1961 | Aechmea fasciata | Germany | |

| 22548 | CBS 744.79 | 1979 | Zygocactus truncatus | Germany | |

| 22550 | CBS 794.70 | 1970 | Albizzia julibrissin | Iran | |

| 22555 | CBS 797.70 | 1970 | Solanum tuberosum | Iran | |

| 22903c | IMI 375363 | 1987 | Pseudotsuga menziesii | Oregon | |

| 25184c | CBS 573.94 | 1994 | Peat | Germany | |

| 25375 | IMI 169612 | 1973 | Human | South Pacific | |

| 25378 | IMI 214661 | 1977 | Human | Oklahoma | |

| 25387 | ATCC 26225 | 1971 | Toenail | New Zealand | |

| 25420 | BBA 66843 | Gossypium sp. | United States | ||

| 25433 | BBA 69050 | Gossypium sp. | China | ||

| 25509 | FRC O-1853 | 1995 | Cyclamen, nonpathogen | The Netherlands | |

| 25512 | FRC O-1858 | 1995 | Cyclamen, nonpathogen | The Netherlands | |

| 25594 | ATCC 16415 | Ipomoea batatas | South Carolina | ||

| 25598 | ATCC 18774 | Soybean | South Carolina | ||

| 25603 | Ploetz A2 | Banana | Australia | ||

| 25728 | CBS 463.91 | 1991 | Human | Germany | |

| 25749 | ATCC 64530 | 1985 | Foot ulcer | Belgium | |

| 26022 | Ploetz JLT44 | Banana | France | ||

| 26024 | Ploetz STB2 | Banana | Honduras | ||

| 26033 | Kistler CL58 | 1996 | Tomato | Florida | |

| 26035 | Kistler Guil2 | 1987 | Phoenix canariensis | Tenerife, Canary Islands | |

| 26178 | Gordon B9-9S | Cucumis melo | Maryland | ||

| 26180 | Gordon CR-III | 1989 | Soil | California | |

| 26203 | Kistler 73 | Tomato | Italy | ||

| 26360 | FRC O-755 | 1975 | Eye | Tennessee | |

| 26361 | FRC O-783 | 1976 | Human | Tennessee | |

| 26362 | FRC O-784 | 1976 | Human | South Carolina | |

| 26363 | FRC O-1168 | 1982 | Peritoneal fluid | Rhode Island | |

| 26365 | FRC O-1562 | 1987 | Brain autopsy | New York | |

| 26367 | FRC O-1591 | 1987 | Human | Maryland | |

| 26368 | FRC O-1723 | 1989 | Amputated toe | California | |

| 26370 | FRC O-1732 | 1989 | Foot | Louisiana | |

| 26372 | FRC O-1746 | 1990 | Catheter, leukemic | New York | |

| 26373 | FRC O-1750 | 1992 | Lung | Chile | |

| 26374 | FRC O-1777 | 1993 | Leg ulcer | California | |

| 26376 | FRC O-1683 | 1988 | Blood | New York | |

| 26381 | Kistler CL-57 | 1996 | Tomato | Florida | |

| 26383 | Kistler GD-40 | 1996 | Tomato | Florida | |

| 26386 | UTHSC 97-95 | 1997 | Lung, unknown fever | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 26387 | UTHSC 96-2463 | 1996 | Sputum, intestinal hemorrhage | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 26388 | UTHSC 96-2063 | 1996 | Peritoneal dialysate | New York | |

| 26389 | UTHSC 96-1960 | 1991 | Nail | Connecticut | |

| 26390 | UTHSC 96-1867 | 1996 | Bronchial wash, lump in chest | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 26391 | UTHSC 96-1804 | 1996 | Bronchial wash, respiratory neoplasm | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 26392 | UTHSC 96-1710 | 1996 | Bronchial wash, bronchitis | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 26393 | UTHSC 96-1087 | 1996 | Nail | Connecticut | |

| 26394 | UTHSC 96-840 | 1996 | Leg ulcer | California | |

| 26395 | UTHSC 95-2234 | 1995 | Whale blowhole | Ohio | |

| 26397 | UTHSC 95-1193 | 1995 | Hand abscess | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 26398 | UTHSC 95-1173 | 1995 | Foot wound | Florida | |

| 26399 | UTHSC 95-1058 | 1995 | Bronchial wash, respiratory failure | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 26400 | UTHSC 95-727 | 1995 | Throat | California | |

| 26401 | UTHSC 95-404 | 1995 | Ointment contaminate | San Antonio, Tex. | Private industrial laboratory A |

| 26402 | UTHSC 95-315 | 1995 | Ointment contaminate | San Antonio, Tex. | Private industrial laboratory A |

| 26403 | UTHSC 95-144 | 1995 | Left calf | Minnesota | |

| 26406 | Gordon K419 | 1989 | Cucumis melo | Jalisco, Mexico | |

| 26409 | ATCC 10913 | Tobacco | Maryland | ||

| 26442 | IMI 141108 | Lilium sp. | South Carolina | ||

| 26551 | UAMH 5692 | 1987 | Leg ulcer | Saskatchewan, Canada | |

| 26677 | FRL F7325 | 1987 | Nail | Sydney, Australia | |

| 26679 | FRL F7463 | 1987 | Gum abscess | Sydney, Australia | |

| 26680 | FRL F8433 | 1989 | Leukemic | Sydney, Australia | |

| 28013 | CDC B-5736 | 1996 | Blood, leukemic | Delaware | |

| 28031 | CDC B-3882 | 1983 | Toe nail | South Carolina | |

| 28244 | BBA 70516 | 1998 | Greenhouse irrigation water | Finland | |

| 28245 | BBA 70517 | 1998 | Greenhouse irrigation water | Finland | |

| 28670 | UWash 97-25989 | 1997 | Sink drain | Seattle, Wash. | Hospital |

| 28678 | UWash 97-25459 | 1997 | Mouthwash | Seattle, Wash. | Hospital, patient B |

| 28680 | UWash 97-9417-2 | 1997 | Lung | Seattle, Wash. | Hospital, patient K |

| 28683 | UWash 98-1455 | 1998 | Mouthwash | Seattle, Wash. | Hospital, patient F |

| 28684 | UWash 97-11584 | 1997 | Mouthwash | Seattle, Wash. | Hospital, patient L |

| 28685 | UWash 93-11340 | 1993 | Enteric stool screen | Seattle, Wash. | Hospital, patient P |

| 28686 | UWash 95-6570 | 1995 | Sinus wash | Seattle, Wash. | Hospital, patient O |

| 28687 | UWash 93-8070 | 1993 | Kidney autopsy | Seattle, Wash. | Hospital, patient E |

| 31166 | Hospital B#9 | 2000 | Renal renal cancer | Houston, Tex. | Hospital B |

| 32176 | Hospital B#F15 | 2000 | Lung cancer, lung autopsy | Houston, Tex. | Hospital B |

| 32377 | Hospital B#B | 2000 | Sputum, leukemic | Houston, Tex. | Hospital B |

| 32507 | FRC O-1885 | 1996 | Sink faucet | Houston, Tex. | Hospital B |

| 32509 | FRC O-1887 | 1996 | Shower drain | Houston, Tex. | Hospital B |

| 32511 | FRC O-1895 | 1996 | Cancer patient | Houston, Tex. | Hospital B |

| 32512 | FRC O-1896 | 1996 | Cancer patient | Houston, Tex. | Hospital B |

| 32513 | FRC O-1908 | 1996 | Cold-water filter | Houston, Tex. | Hospital B |

| 32514 | FRC O-1909 | 1997 | Cold-water filter | Houston, Tex. | Hospital B |

| 32515 | FRC O-1910 | 1997 | Cold-water filter | Houston, Tex. | Hospital B |

| 32516 | FRC O-1911 | 1997 | Cold-water filter | Houston, Tex. | Hospital B |

| 32517 | FRC O-1912 | 1997 | Cold-water filter | Houston, Tex. | Hospital B |

| 32525 | PD 22005805-2 | 2002 | Tomato seed | The Netherlands | |

| 32527 | PD 22005805-4 | 2002 | Tomato seed | The Netherlands | |

| 32914 | UTHSC 01-1015 | 2001 | BAL | California | |

| 32915 | UTHSC 01-1482 | 2001 | Leg | Colorado | |

| 32916 | UTHSC 01-1998 | 2001 | Blood CVC, esophageal cancer | Houston, Tex. | Hospital B |

| 32917 | UTHSC 01-2476 | 2001 | Foot, cellulitis | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32920 | UTHSC 02-1874 | 2002 | Periesophageal | Washington, D.C. | |

| 32921 | UTHSC 02-1980 | 2002 | Water supply | Baltimore, Md. | Hospital |

| 32922 | UTHSC 00-2402 | 2000 | Environmental | San Antonio, Tex. | Private industrial laboratory B |

| 32925 | UTHSC 00-1311 | 2000 | Food | San Antonio, Tex. | Private industrial laboratory B |

| 32927 | UTHSC 00-221 | 2000 | Meatus | San Antonio, Tex. | Commercial laboratory |

| 32929 | UTHSC 99-1742 | 1999 | BAL | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32930 | UTHSC 99-1135 | 1999 | BAL, AIDS | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32931 | UTHSC 99-853 | 1999 | Blood | Massachusetts | |

| 32932 | UTHSC 98-2469 | 1998 | Blood | Pennsylvania | |

| 32933 | UTHSC 98-2404 | 1998 | BAL, pneumonia | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32935 | UTHSC 98-2189 | 1998 | Blood | Maine | |

| 32938 | UTHSC 98-1748 | 1998 | BAL, dysphagia | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32939 | UTHSC 98-1747 | 1998 | BAL | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32940 | UTHSC 98-1741 | 1998 | BAL, malignant neoplasm | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32941 | UTHSC 98-1670 | 1998 | Spleen, splenomegaly | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32942 | UTHSC 98-1645 | 1998 | BAL | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32943 | UTHSC 98-835 | 1998 | BAL, pneumonia | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32944 | UTHSC 98-834 | 1998 | BAL | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32945 | UTHSC 98-718 | 1998 | Lung, unspecified neoplasm | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32946 | UTHSC 98-709 | 1998 | Nail | Connecticut | |

| 32947 | UTHSC 98-361 | 1998 | BAL | Colorado | |

| 32948 | UTHSC 97-2184 | 1997 | BAL, nodular goiter | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32949 | UTHSC 97-2090 | 1997 | BAL, mass in chest | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32950 | UTHSC 97-1922 | 1997 | BAL, asthma | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32951 | UTHSC 97-1684 | 1997 | BAL, malignant neoplasm | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32952 | UTHSC 97-1055 | 1997 | Toe bone | Wisconsin | |

| 32953 | UTHSC 97-1476 | 1997 | Open leg wound | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32954 | UTHSC 97-1466 | 1997 | BAL | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32955 | UTHSC 97-1465 | 1997 | BAL, bronchitis | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32956 | UTHSC 97-1184 | 1997 | BAL, voice disturbance | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32957 | UTHSC 97-891 | 1997 | BAL, bronchitis | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32958 | UTHSC 97-476 | 1997 | Lung wash, hemoptysis | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32960 | UTHSC 97-357 | 1997 | BAL, pneumonia | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32961 | UTHSC 97-291 | 1997 | BAL | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32962 | UTHSC 97-290 | 1997 | BAL, CVA | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 32999 | UTHSC 97-2110 | 1997 | Sputum, respiratory failure | San Antonio, Tex. | Hospital A |

| 34936 | Di Pietro 4287 | 1984 | Tomato | Spain | |

| 36064 | FRC O-1747 | 1991 | Human cancer | Houston, Tex. | Hospital B |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.; BBA, Biologische Bundesanstalt für Land-und Forstwirtschaft, Institute für Mikrobiologie, Berlin, Germany; CBS, Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.; Di Pietro, Antonio Di Pietro, Universidad de Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain; FRC, Fusarium Research Center, The Pennsylvania State University, State College; FRL, Fusarium Research Laboratory, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia; Gordon, Thomas Gordon, University of California, Davis; Hospital B, Hospital B, Houston, Tex. (13); IMI, CABI Biosciences, Egham, Surrey, England; PD, Plantenziektenkundige Dienst, Wageningen, The Netherlands; Ploetz, Randy Ploetz, University of Florida, Homestead; UAMH, Microfungus Collection, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada; UTHSC, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio; UWash, University of Washington, Seattle.

With the exception of strain NRRL 26395 from a whale blowhole, all other clinical isolates are from humans. BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; CVA, cough variant asthma; CVC = central venous catheter.

DNA isolation, amplification, and sequencing.

Liquid cultures were grown in yeast-malt broth, and total genomic DNA was extracted from freeze-dried mycelia by the hexadecyltrimethyl-ammonium bromide (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) protocol described by O'Donnell et al. (20). All PCR and sequencing primers are listed in Table 2. The total reaction volume of all PCR mixtures was 50 μl and included approximately 5 ng of total genomic DNA and MgCl2 at a final concentration of 25 mM. Amplification of a portion of the translation elongation factor (1α) gene and the mitochondrial small-subunit (mtSSU) ribosomal DNA (rDNA) was accomplished by using the EF-1-EF-2 (21) and MS1-MS2 (35) PCR primer pairs, respectively, and AmpliTaq (Applied Biosystems [ABI], Foster City, Calif.) in a 9700 thermocycler and the following cycling parameters: 1 cycle of 30 s at 94°C; 40 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 52°C, and 90 s at 72°C; and then 10 min at 72°C and a 4°C soak. The entire nuclear ribosomal intergenic spacer (IGS) region (∼2.5 kb) was amplified with the NL11-CNS1 primer pair (Table 2), using Platinum Taq DNA polymerase Hi-Fi (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, Calif.) in an ABI 9700 thermocycler and the following cycling parameters: 1 cycle of 90 s at 94°C; 40 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 52°C, and 3 min at 68°C; and then 1 cycle of 5 min at 68°C and a 4°C soak.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for PCR, DNA sequencing, and AFLP genotyping

| Primer | Locus | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a |

|---|---|---|

| EF-1 | EF-1α | ATGGGTAAGGARGACAAGAC |

| EF-11ta | EF-1α | GTGGGGCATTTACCCCGCC |

| EF-22t | EF-1α | AGGAACCCTTACCGAGCTC |

| EF-2 | EF-1α | GGARGTACCAGTSATCATG |

| MS1 | mtSSU rDNA | CAGCAGTCAAGAATATTAGTCAATG |

| MS2 | mtSSU rDNA | GCGGATTATCGAATTAAATAAC |

| MS21 | mtSSU rDNA | CTCTCCTCCTCAAGTACTGC |

| GFM136 | MAT1-1 | ATGGTCTACAGCCAGTCGCA |

| FOM132 | MAT1-1 | GGTAGTGTTGTTTGTGGTTG |

| FOM122 | MAT1-1 | TCCATGCCAAGATCCTCAGC |

| FOM123 | MAT1-1 | AAGGCAGAGTCAGAAATCCA |

| FOM112 | MAT1-1 | GCTGCTGCATCTTGGATTGC |

| FOM111 | MAT1-1 | GCTTGATCTGTTCGGTCATG |

| FOM211 | MAT1-2 | ACATATCGATAGCATCTACC |

| FOM212 | MAT1-2 | AGGCGGTAATCTGCTGTGTA |

| NL11 | IGS rDNA | CTGAACGCCTCTAAGTCAG |

| OCNL13 | IGS rDNA | TGTGATGTATGCGGTCCTAGG |

| ONL13B | IGS rDNA | GGTTCGAGGATCGATTCGAGG |

| OCNS3C | IGS rDNA | GCAAGATCTGATACTGAGAGG |

| CNS1 | IGS rDNA | GAGACAAGCATATGACTAC |

| EcoRI-a | Adapter | CTCGTAGACTGCGTACC |

| EcoRI-b | Adapter | AATTGGTACGCAGTCTAC |

| MseI-a | Adapter | GACGATGAGTCCTGAG |

| MseI-b | Adapter | TACTCAGGACTCAT |

| EcoRI-ns | Nonselective | GACTGCGTACCAATTC |

| MseI-ns | Nonselective | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAA |

| EcoRI-CC | Selective | 6-FAM-GACTGCGTACCAATTCCC |

| EcoRI-TC | Selective | 6-FAM-GACTGCGTACCAATTCTC |

| MseI-G | Selective | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAAG |

R, AG; S, CG.

The sequences with GenBank accession numbers AB011379 and AB011378 were used to design PCR primers to amplify the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 idiomorphs, respectively (38). The MAT1-1 idiomorph was amplified as two overlapping segments by using the FOM132-FOM123 and FOM122-FOM111 primer pairs (Table 2), using the Platinum Taq PCR protocol described above. PCR primers FOM211 and FOM212 were used to amplify the MAT1-2 idiomorph, using the AmpliTaq PCR protocol described above. A multiplex PCR, employing the FOM111-FOM112 primer pair for the MAT1-1-2 gene and the FOM211-FOM212 primer pair for the MAT1-2-1 gene, was used to screen all of the strains included in this study for MAT idiomorph (i.e., MAT1-1 or MAT1-2), using the AmpliTaq PCR protocol outlined above.

PCR products were purified by using Montage PCR96 Cleanup filter plates (Millipore Corp., Billerica, Mass.) and then sequenced by using ABI BigDye chemistry version 3.0 in a 9700 thermocycler with the following cycling parameters: 1 cycle of 15 s at 96°C; 40 cycles of 15 s at 96°C, 10 s at 50°C, and 4 min at 60°C; and then a 4°C soak. Sequencing reaction mixtures were purified via ethanol precipitation and then run on an ABI 3100 or 3730 genetic analyzer. Sequences were edited and aligned by using Sequencher version 4.1.2 (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, Mich.), after which the alignments were improved manually.

AFLP analysis.

All genomic DNA samples included in the AFLP analysis were first treated with 2 μl of RNase A (10 μg/μl) (Sigma) per 200-μl total genomic DNA sample for 30 min at 65°C, after which they were subjected to a lithium chloride (Sigma) cleanup protocol. Briefly this protocol consisted of adding an equal volume of ice-cold 5 M LiCl to each genomic DNA, icing for 15 min, and then centrifuging at 13,000 × g for 15 min. After the supernatant was removed to a fresh tube, 1/16 volume of 5 M NaCl was added to each sample, followed by 2 volumes of ice-cold 95% ethanol. The samples were then placed in a −80°C freezer for 20 min to precipitate the DNA. Once the samples were removed from the freezer and thawed, DNAs were pelleted in a microcentrifuge at 13,000 × g for 10 min, followed by a 70% ethanol wash, and they were then resuspended in 50 μl double-distilled water (ddH2O). DNA quantification of all genomic DNA samples was done by running them into a 1.5% agarose gel together with a known concentration of a HindIII (A↓AGCTT) digest of λ DNA (New England Biolabs [NEB], Beverly, Mass.). Restriction-ligation was conducted at 37°C overnight in an ABI 9700 thermocycler in a total volume of 10 μl by combining ∼100 ng of total genomic DNA in 4.5 μl of ddH2O with 5.5 μl of the following master mix: 1 μl of 10× T4 ligase buffer (NEB) (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM ATP, 25 μg of bovine serum albumin [BSA] per ml), 1 μl of NaCl (0.5 M), 0.5 μl of 10× BSA (1 μg/μl), 1 μl of MseI adapter mix (50 pmol/μl), 1 μl of EcoRI (G↓AATTC) adapter mix (5 pmol/μl), and 1 μl of an enzyme master mix (for each set of 10 reactions) consisting of 1 μl of 10× T4 DNA ligase buffer (NEB), 1 μl of NaCl (0.5 M), 0.5 μl of 10× BSA (1 μg/μl), 0.5 μl of EcoRI (NEB) (100 U/μl), 0.2 μl of MseI (T↓TAA) (NEB) (50 U/μl), 0.33 μl of T4 DNA ligase (NEB) (2,000 U/μl), and 6.5 μl of ddH2O. All adapters and primers used for the AFLP analysis are listed in Table 2. Once completed, the restriction-ligation mix was diluted 1:2 in ddH2O and stored at −20°C when not in use.

The preselective amplification was performed in a total volume of 10 μl by first aliquoting 8 μl of a master mix consisting of 1 μl of 10× Invitrogen PCR buffer, 1 μl of 2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 0.5 μl of 50 mM MgCl2, 1 μl of EcoRI nonselective primer (1 pmol/μl), 1 μl of MseI nonselective primer (1 pmol/μl), 0.065 μl of Taq polymerase (Invitrogen), and 3.5 μl of ddH2O into each reaction tube, to which 2 μl of a diluted restriction-ligation mix was added. Amplifications were performed in an ABI 9700 thermocycler programmed as follows: 2 min at 72°C followed by 5 min at 94°C; 20 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 56°C, and 60 s at 72°C; and 1 cycle of 5 min at 72°C followed by a 4°C soak. Several amplification product mixtures were checked for a smear of DNA in the range of 100 to 800 bp, which is indicative of a successful preselective amplification, by electrophoreses of 5 μl of the reaction products into a 1.5% agarose gel, followed by staining with ethidium bromide and visualization over a UV transilluminator. Preselective amplicons were diluted 1:11 with ddH2O, after which they were vortexed briefly and then stored at −20°C when not in use.

The selective amplification was performed in a total volume of 10 μl by first dispensing 8-μl aliquots of a master mix consisting of 1 μl of 10× Invitrogen PCR buffer, 1 μl of 2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 0.5 μl of 50 mM MgCl2, 1 μl of either EcoRI-CC or EcoRI-TC 6-FAM-labeled selective primer (Qiagen, Alameda, Calif.) (Table 2), 1 μl of MseI-G selective primer (3 pmol/μl), 0.065 μl of Invitrogen Taq polymerase, and 3.5 μl of ddH2O, to which 2 μl of a diluted preselective amplicon was then added. Selective amplifications were performed in an ABI 9700 thermocycler programmed as follows: 3 min at 94°C; 9 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 65°C, and then ramping down 1°C/cycle from 65 to 57°C, followed by 60 s at 72°C; 40 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 56°C, and 60 s at 72°C; and then 1 cycle of 5 min at 72°C followed by a 4°C soak. Amplifications were checked by running 5 μl of several amplicons into a 1.5% agarose gel as described above. Selective amplification mixtures were diluted 1:10 or 1:20 in ddH2O, after which 1.5 μl of each mixture was added to a master mix consisting of 9.7 μl of HighDye formamide (ABI) and 0.3 μl of the GeneScan ROX 500 (ABI) size standard. All samples were run on an ABI 3100 genetic analyzer, using the GeneScan version 3.7 analysis software default run module for data collection and GenoTyper version 3.7 for scoring fragments in the range of 50 to 500 bp relative to the ROX 500 size standard. Only electropherogram peaks above 100 fluorescent units were scored for the presence or absence of bands of the same size. Reproducibility of the AFLP data was assessed by running two exemplars of each unique AFLP haplotype through the entire protocol, starting from the beginning with the isolation of total genomic DNA (15). Only bands detected in the duplicate AFLP analyses (90%) were included in the phylogenetic analyses.

Phylogenetic analysis.

The MLST and AFLP matrices analyzed in the present study are available at http://www.ncaur.usda.gov/MGB/MGB-O'Donnell.htm. All phylogenetic analyses were conducted with PAUP* version 4.0b10 (28). Searches for the most-parsimonious trees (MPTs) used a heuristic search with 1,000 random addition replicates and tree bisection with reconnection branch swapping, after excluding ambiguously aligned nucleotide positions. The Templeton Wilcoxon signed rank (WS-R) test implemented in PAUP* was used to assess whether the various partitions could be combined, using 70% bootstrap majority rule trees from each partition as constraints. Results of the WS-R tests (P = 1.0) indicated that all of the partitions could be combined. Clade stability was assessed via parsimony bootstrapping in PAUP*, using a heuristic search with 1,000 pseudoreplications of the data and 10 random addition sequences per replicate and tree bisection with reconnection branch swapping. Constraints forcing the monophyly of all of the clinical isolates and all of the clinical isolates within clade 3 were compared with the MPTs by using the Kishino-Hasegawa test in PAUP*. Phylograms were either midpoint rooted or outgroup rooted based on more inclusive phylogenetic analyses (2, 21, 27).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences determined in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers AY527415 to AY527732.

RESULTS

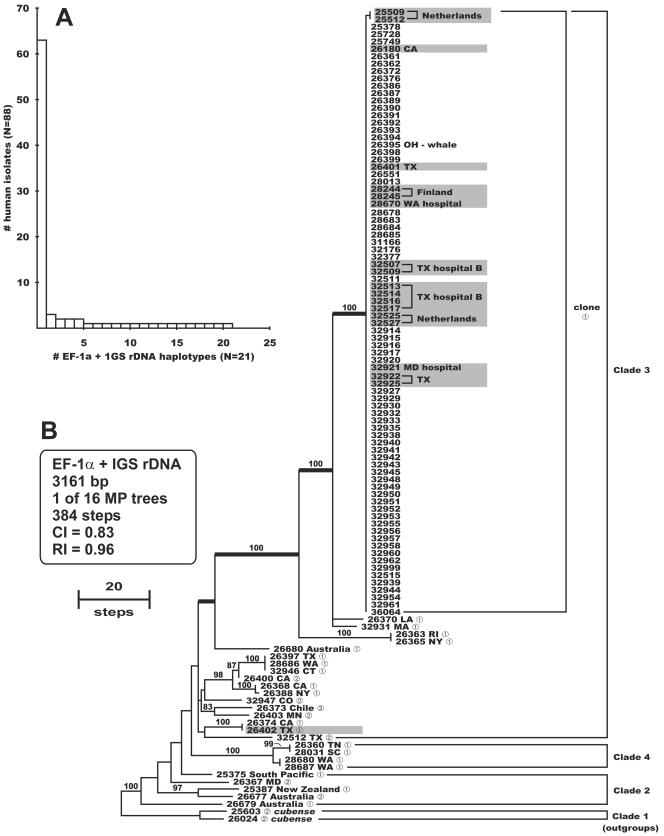

The genetic relatedness and diversity of FOC isolates from patients associated with a pseudoepidemic at a San Antonio, Tex., hospital that peaked in 1997 to 1998 (hospital A) were investigated together with those of isolates collected from the hospital water systems of three U.S. hospitals by comparing them with a geographically diverse set of 88 clinical and 18 environmental isolates from the FOC (Table 1). Aligned partial DNA sequences of translation elongation factor (EF-1α, 655 bp) and the entire nuclear ribosomal intergenic spacer region (IGS rDNA, 2,510 bp) were analyzed phylogenetically, using sequences of two strains of the banana pathogen F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense (NRRL 25603 and 26024) to root the trees based on a more inclusive phylogenetic analysis (21). Results of the Templeton WS-R combinability test (P = 1.0) implemented in PAUP* (28), using 70% bootstrap consensus trees as constraints, indicated that the EF-1α and IGS rDNA partitions could be analyzed as a combined data set. Maximum-parsimony analysis of the combined data set resolved 21 unique EF-1α-IGS rDNA haplotypes among the 88 clinical isolates (Fig. 1), including one widespread clonal lineage which accounted for 63 (72%) of the clinical isolates and 17 out of 18 of the nonclinical isolates. Of the 82 strains of the clonal lineage sequenced, 80 shared an identical EF-1α-IGS rDNA haplotype, while the other two strains, which were isolated as saprophytes of cyclamen in The Netherlands (36), differed from other members of the clonal lineage by only a single base pair mutation within the IGS rDNA (Fig. 1B). All 33 isolates from the Texas hospital A pseudoepidemic are members of the clonal lineage. By comparison, 16 of the 21 EF-1α-IGS haplotypes associated with patients were represented by singletons, with the second most common haplotype being represented by only three strains (Fig. 1A). Eight of the 17 nonclinical isolates of the clonal lineage were recovered from the water systems of geographically distant hospitals in Houston, Tex., in 1996 to 1997 (1, 14); Seattle, Wash., in 1997; and Baltimore, Md., in 2002. Strains of the clonal lineage were also recovered from clinical cases in Canada, Belgium, and Germany; from a greenhouse irrigation system in Finland where tomatoes were being grown; and from tomato seed and cyclamen in The Netherlands.

FIG. 1.

(A) Distribution of the 88 human isolates among the 21 EF-1α-IGS rDNA sequence haplotypes. (B) One of 16 most-parsimonious phylograms inferred from the combined EF-1α-IGS rDNA sequence data rooted with sequences of F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense NRRL 25603 and 26024 from clade 1 of the FOC (21). All ingroup strains are from humans, except for strain NRRL 26395 from a whale and the 18 environmentalisolates indicated by shading. Note that 82 of the ingroup strains are members of a widespread clonal lineage. The number 1 or 2 following the five-digit NRRL culture collection number indicates that the strain was typed by the mating-type (MAT) idiomorph PCR assay as MAT1-1 or MAT1-2, respectively. All strains of the clonal lineage and the five most closely related strains are MAT1-1 (identified by boldface internodes). Internodes supported by bootstrap values of ≥70% are indicated.

To further characterize their population biology, all of the strains were subjected to a mating type (MAT) idiomorph test, using primer pairs FOM111-FOM112 and FOM211-FOM212 for MAT1-1 and MAT1-2, respectively. This assay revealed that all 82 strains of the clonal lineage and strains of the four most closely related haplotypes possess a MAT1-1 idiomorph (Fig. 1B). In addition, strains representing 14 of the 21 unique EF-1α-IGS haplotypes from patients were MAT1-1, compared with only 7 MAT1-2 strains, which were all associated with singleton haplotypes (Fig. 1B).

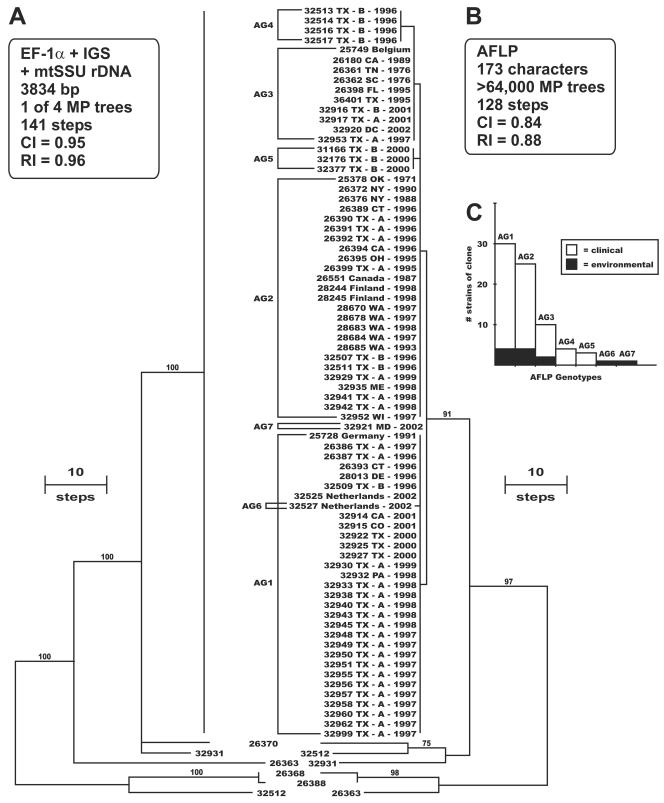

Further MLST characterization of 74 strains of the clonal lineage from clinical and environmental sources was conducted, together with that of strains representing six different EF-1α-IGS rDNA haplotypes, using partial EF-1α (651 bp) and mtSSU rDNA (677 bp) sequences and the entire IGS rDNA (2,506 bp). Maximum-parsimony analysis of the combined data set, totaling 3.8 kb (Table 1), revealed that 74 strains of the clonal lineage included in this analysis had an identical MLST (Fig. 2A). In an effort to obtain a finer level of genetic discrimination, these strains were subjected to AFLP genotyping, using two combinations of EcoRI plus 2-bp 6-FAM-labeled selective primers together with an MseI plus 1-bp selective primer (Table 2). Parsimony analysis of the AFLP matrix, consisting of 173 binary characters (i.e., restriction fragments ranging from 50 to 500 bp were coded as 1 for present and 0 for absent), yielded >64,000 MPTs of 128 steps in length (Fig. 2B) (consistency index [CI] = 0.84; retention index [RI] = 0.88) in which the clonal lineage formed a highly similar exclusive group consisting of only seven unique AFLP genotypes (AG1 to -7) (Fig. 2C). AFLP genotyping of the two saprobic strains isolated from cyclamen in The Netherlands (NRRL 25509 and NRRL 25512) revealed that they possess the AG2 AFLP genotype (data not shown). When the AFLP data for 74 strains of the clonal lineage were analyzed separately, the MPTs were only seven steps in length (CI = 0.86; RI = 0.98) as 167 of the 173 characters were identical across all strains (five polymorphic sites were synapomorphic and one was autapomorphic). Of the 28 clinical strains from hospital A in San Antonio, Tex. (where the pseudoepidemic was reported) that were subjected to AFLP fingerprinting, representatives of the three most common AFLP genotypes were recovered between 1996 and 2001 (AG1, n = 19; AG2, n = 7; and AG3, n = 2). Similarly, five AFLP genotypes of the clonal lineage (i.e., AG1 to -5) were recovered during the same time frame from hospital B in Houston, Tex., including a hospital environmental isolate that shared the identical AG2 genotype with an isolate from a patient (NRRL 32507 and NRRL 32511, both isolated in 1996). Matched patient-environment isolates of the AG2 genotype (NRRL 28670 and NRRL 28678) were also recovered in 1997 from a Seattle, Wash., hospital.

FIG. 2.

(A) One of four most-parsimonious midpoint rooted phylograms inferred from the combined EF-1α-IGS rDNA-mtSSU rDNA sequence data for the 80-taxon matrix. (B) One of >64,000 most-parsimonious phylograms inferred from the AFLP data, indicating the seven AFLP genotypes (AG1 to -7) for 74 strains of the widespread clonal lineage. Geographic origin and year isolated are indicated. A, San Antonio, Tex., hospital A, reporting the pseudoepidemic; B, Houston, Tex., hospital B, reporting the water system as a potential reservoir of nosocomial fusariosis (1, 14). Internodes supported by bootstrap values of ≥70% are indicated. (C) Distribution of 74 clinical and environmental strains of the widespread clonal lineage among the seven AFLP genotypes.

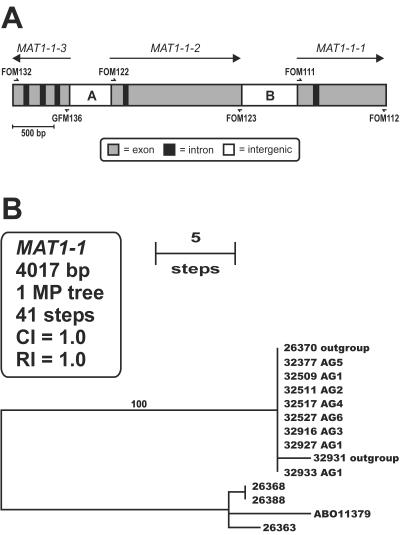

Genetic relationships among the AFLP genotypes were investigated further by PCR amplification and sequencing of the entire MAT1-1 idiomorph from one or more strains representing the six most common AFLP genotypes (i.e., AG1 to -6) of the clonal lineage and strains of five near relatives (Fig. 3), using PCR primers described by Yun et al. (38) (Table 2). Parsimony analysis of the 4,017 aligned MAT1-1 nucleotide characters yielded a single MPT of 41 steps (Fig. 3B) (CI = 1.0) in which exemplars of the six AFLP genotypes were identical (e.g., NRRL 26370) or nearly identical (e.g., NRRL 32931) to the two closest known relatives of the clonal lineage (Fig. 1B), reflecting the high conservation of the MAT genes, which have been shown to be under strong purifying selection (23). Hypothetical translations of the three MAT1-1 genes suggest that they all encode functional proteins (GenBank accession numbers AY527415 to AY527427).

FIG. 3.

(A) MAT1-1 idiomorph showing coding and noncoding regions and directions of transcription of the three MAT genes. PCR and sequencing primers are indicated by half-arrows (Table 2). The two intergenic regions are arbitrarily designated A and B. (B) Single most-parsimonious midpoint rooted phylogram inferred from the MAT1-1 nucleotide sequence data. Note that strains representing six AFLP genotypes (AG1 to -6) of the clonal lineage are identical to one another and to outgroup strain NRRL 26370 (100% bootstrap support). The AB011379 MAT1-1 sequence was obtained from GenBank.

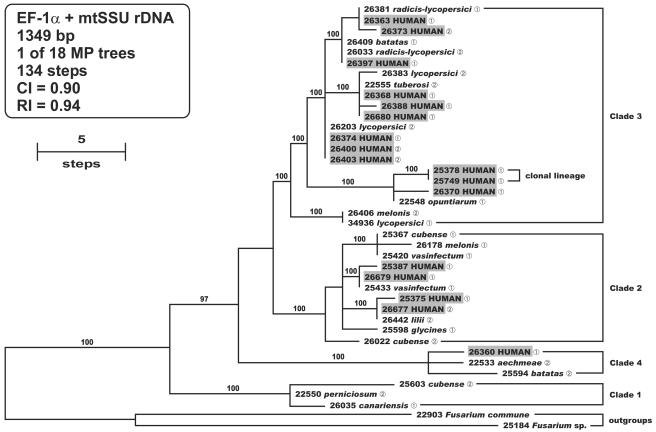

Finally, to address whether isolates from patients have monophyletic or multiple independent evolutionary origins within the FOC, parsimony analyses were conducted on aligned partial EF-1α (655 bp) and mtSSU rDNA (694 bp) sequences representing 17 strains from patients and 21 phytopathogenic strains chosen to represent the known pathogenic diversity of the FOC (2, 21). Parsimony analysis of the combined data set (1,349 bp) yielded 18 MPTs of 134 steps in length (CI = 0.90; RI = 0.94) with human isolates nested within three of the four clades (Fig. 4). However, most of the human isolates, including those of the widespread clonal lineage, were nested in clade 3, the most phylogenetically diverse clade. Constraints forcing the monophyly of the human isolates within clade 3 and all of the human isolates within the FOC in separate analyses were 11 and 33 steps longer, respectively, and significantly less parsimonious than the MPTs (Kishino-Hasegawa test, P = 0.009 and P < 0.0001, respectively). Results of the MAT idiomorph test revealed that MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 strains are represented in all four clades.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic diversity of human isolates within the F. oxysporum complex inferred from parsimony analysis of the combined EF-1α-mtSSU rDNA sequence data. The human isolates exhibit a polyphyletic distribution among three of the four clades. The widespread clonal lineage is nested within clade 3. Internodes supported by bootstrap values of ≥70% are indicated. Sequences of Fusarium commune NRRL 22903 and Fusarium sp. strain NRRL 25184 were used as outgroups to root the phylogram.

A summary of the tree statistics is given in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Tree statistics and summary sequence

| No. of taxa | Data set | No. of:

|

Tree length (steps) | CI | RI | P (WS-R)c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characters | PICa | Autb | MPTs | ||||||

| 109 | EF-1α | 651 | 44 | 9 | 4 | 56 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| 109 | IGS rDNA | 2,510 | 144 | 107 | 63 | 312 | 0.84 | 0.96 | |

| 109 | EF-1α + IGS rDNA (Fig. 1B) | 3,161 | 188 | 116 | 16 | 384 | 0.83 | 0.96 | 1.0 |

| 80 | EF-1α | 651 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 12 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| 80 | IGS rDNA | 2,506 | 61 | 54 | 2 | 118 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |

| 80 | mtSSU rDNA | 677 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| 80 | EF-1α + IGS rDNA | 3,157 | 67 | 60 | 4 | 132 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 1.0 |

| 80 | EF-1α + mtSSU rDNA | 1,328 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 17 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 80 | IGS rDNA + mtSSU rDNA | 3,183 | 65 | 55 | 2 | 127 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 1.0 |

| 80 | EF-1α + IGS + mtSSU (Fig. 2A) | 3,834 | 71 | 61 | 4 | 141 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 1.0 |

| 80 | AFLP D | 87 | 37 | 23 | >100 | 68 | 0.88 | 0.93 | |

| 80 | AFLP E | 86 | 29 | 18 | >100 | 57 | 0.82 | 0.86 | |

| 80 | AFLP D + E (Fig. 2B) | 173 | 66 | 41 | >64,000 | 128 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 1.0 |

| MAT1-1 idiomorph (Fig. 3B) | 4,017 | 32 | 9 | 1 | 41 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 41 | mtSSU rDNA | 694 | 16 | 19 | >100 | 46 | 0.91 | 0.95 | |

| 41 | EF-1α | 655 | 42 | 31 | 9 | 84 | 0.93 | 0.96 | |

| 41 | mtSSU rDNA + EF-1α (Fig. 4) | 1,349 | 58 | 50 | 18 | 134 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 1.0 |

PIC, parsimony informative characters (i.e., synapomorphies).

Aut, autapomorphies.

Probability, using the W-SR test, of getting a more extreme T value, with the null hypothesis being no difference between the two trees.

DISCUSSION

This study describes the first MLST- and AFLP-based molecular markers for genotyping clinically important members of the FOC. These tools were used in a molecular epidemiological investigation of a pseudoepidemic in hospital A in San Antonio, Tex., that peaked in 1997 to 1998 (S. E. Sanche, D. A. Sutton, K. Magnon, R. Cox, S. Revankar, and M. G. Rinaldi, Abstr. 98th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. F-102, 1998) and in a survey of the water systems of three U.S. hospitals suspected as being reservoirs of nosocomial fusariosis. The major finding of this study, based on concordant results from phylogenetic analyses of multilocus DNA sequence data and AFLPs, is that a geographically widespread clonal lineage comprises >70% of all FOC clinical isolates, including all of the strains recovered from the hospital A pseudoepidemic and from the water systems of a hospital in Houston, Tex. (hospital B) (1, 14) and of hospitals in Baltimore, Md., and Seattle, Wash. This clonal lineage consisted of only seven highly similar AFLP genotypes, and all of its members shared identical or nearly identical EF-1α and IGS rDNA sequences and possessed only MAT1-1 idiomorphs, indicating that they were of clonal origin. To date, molecular epidemiological studies that have identified fungal pathogens with a highly clonal population structure are restricted to a relatively small number of clinically (8, 9), zoologically (17), and agriculturally (4, 5, 11) important species, including members of the FOC (13, 29). However, most clinically important fungi investigated to date exhibit both clonality and recombination (reviewed in references 31 and 37).

Lacking the ability to satisfy Koch's postulates regarding FOC isolates from patients, we cannot distinguish isolates capable of infecting humans from other isolates, including potential secondary invaders or superficial environmental isolates not involved in infection. The frequent reoccurrence of the same MLST and AFLP genotypes from patients in different geographic regions, however, strongly suggests that these isolates are the etiological agents of these infections. Further study comparing the pathogenic potentials of different members of the FOC by utilizing animal and other models of pathogenicity (6, 24) is needed to shed light on this issue. However, if differences in pathogenic potential exist among the 74 members of the major clonal lineage associated with patients, they are not reflected in the extremely low level of genetic diversity observed.

The results of the present study support the findings of Anaissie et al. (1), who reported a possible molecular match between strains of F. oxysporum from a patient and the environment from Houston, Tex., hospital B, where the initial environmental survey for nosocomial fusaria was conducted (14). The two isolates had similar banding patterns based on random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD), interrepeat PCR, and restriction fragment-length polymorphism analyses conducted at the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md. However, the authors of that study were conservative in not classifying this patient-environment isolate pair as a match because a RAPD analysis conducted at a second laboratory yielded discordant results. Because this pair of isolates was conclusively shown to be a member of the FOC widespread clonal lineage in the present study (Fig. 1B) (NRRL 32507 and NRRL 36064), it is clear that the RAPD results from the second laboratory in Houston represent a false negative. In all, 13 of the 14 FOC strains (i.e., 92.8%) that were isolated at Houston hospital B from cancer patients and the environment from 1991 through 2001 were conclusively shown to be members of the FOC clonal lineage via MLST and AFLP analyses (Table 1). The 13 isolates of the clonal lineage from hospital B included 6 of the 7 isolates from cancer patients and all 7 isolates isolated from the hospital water system by Kuchar (14) in 1996 and 1997.

Paradoxically, a separate molecular epidemiological study, also conducted at Houston, Tex., hospital B in 1996 and 1997, reported a complete mismatch between 15 environmental fusaria isolated by Kuchar (14) and 10 clinical isolates compared with them by means of RAPD data (25). Two nonexclusive scenarios are offered to explain the discordant results of Anaissie et al. (1) and Raad et al. (25). First, because most of the fusaria isolated at hospital B were members of the F. solani species complex (1, 14), it is possible that strains of the FOC clonal lineage may not have been included in the latter study, because isolates were not identified by species names. Second, reproducibility of the RAPD data may have been an issue in the study by Raad et al. (25). Due to problems of reproducibility and portability from laboratory to laboratory, RAPD and other forms of nondiscrete DNA data are rapidly being replaced with electronically portable MLST schemes (30).

Because most members of the FOC clonal lineage from San Antonio, Tex., hospital A were recovered from bronchoalveolar lavage specimens, as in numerous other nosocomial outbreaks and pseudoepidemics (http://www.umdnj.edu/rspthweb/bibs/fob_infc.htm), contaminated bronchoscopes or inadequate bronchoscope sterilization was suspected, but not proven, as the source of the contamination. Our molecular markers provided conclusive evidence that the AG2 genotype of the clonal lineage recovered from the water systems of hospital B in Houston, Tex., in 1996 and a Seattle, Wash., hospital in 1997 was a precise molecular match with strains recovered from cancer patients at these hospitals during the same years, suggesting potential nosocomiality. Similarly, AFLP markers have shown that some waterborne environmental isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus are genetically identical to those from hospital patients with invasive aspergillosis (34). The FOC clonal lineage may be widespread in hospital water systems within the United States, because four virtually identical AFLP genotypes of it were recovered from the three hospitals surveyed, including environmental isolates of the AG1, AG2, and AG4 genotypes from hospital B in 1996 (14). Not surprisingly, water also appears to serve as a reservoir for nonhospital environmental isolates of the FOC clonal lineage, because the AG2 genotype was isolated from a greenhouse irrigation system in Finland where tomatoes were being grown and from the blowhole of a whale at a marine park in Ohio. Other potential environmental sources of the clonal lineage include agricultural soils (AG3, San Joaquin, Calif.) and industrial laboratories (AG1 and AG3, San Antonio, Tex.). Based on these observations, we hypothesize that any water source within and outside a hospital may be a potential reservoir for the FOC clonal lineage, and we suggest careful screening of all water sources that come in contact with immunocompromised patients.

Intercontinental distributions of the AG1, AG2, and AG3 genotypes in Europe and North America suggest recent dispersion that may have resulted from the relatively recent global trade of horticultural and agricultural plants and plant products. This scenario is consistent with the fact that members of the FOC are ubiquitous inhabitants of plants (e.g., NRRL 25509 and NRRL 25512 were isolated as nonpathogens of cyclamen in The Netherlands) (36). Vigilant surveillance of the clonal lineage within U.S. hospitals seems warranted, because it has been recovered in 16 different states, including from hospital water systems in Texas, Maryland, and Washington (Table 1). One surprise of this study is that the clonal lineage is phylogenetically distinct from all of the plant pathogens in our MLST database, which includes partial EF-1α-mtSSU rDNA sequences from over 700 FOC strains. Although this finding does not preclude the possibility that the clonal lineage is a plant pathogen, it suggests that it may not be economically significant, because most described phytopathogens within the FOC are represented in our database. The present study extends our current knowledge of FOC phylogeny (2, 21) through the discovery of a fourth clade containing the only strain isolated from a human eye infection (Fig. 4). Another surprise to emerge from the present study is the extreme rarity of eye infections caused by members of the FOC (i.e., only 1 of 88 among the human isolates), especially when compared with the F. solani species complex, where 43.5% of the clinical isolates subjected to MLST genotyping (i.e., 121 of 278) were recovered from ocular mycoses (N. Zhang et al., unpublished data). Because fusaria are opportunistic pathogens of humans, it was not surprising to discover the clinical isolates exhibit independent evolutionary origins within three of the FOC clades as well as support for a polyphyletic origin of human isolates within clade 3. This finding parallels studies of several plant pathogens within the FOC that appear to have evolved host specificity polyphyletically (2, 21, 26).

Although no member of the FOC has been shown to undergo a sexual cycle, our mating-type multiplex PCR assay demonstrated that all of the FOC strains included in this study possess either a MAT1-1 or a MAT1-2 idiomorph but not both. Three lines of evidence suggest that members of the FOC may undergo a cryptic sexual cycle: (i) MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 mating-type genes are expressed and processed correctly, and translations of the MAT genes that we sequenced suggest that they encode functional proteins (38; C. Waalwijk, K. Venema, P. Dyer, and G. Kema, Program 20th Fungal Genet. Conf., abstr. 187, 1999); (ii) MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 strains are represented in all four clades of the FOC, which indicates that MAT genes have been maintained within this complex on an evolutionary time scale that spans multiple speciation and cladogenic events; and (iii) MAT genes appear to be under strong purifying selection (23). Alternatively, two nonexclusive explanations of the long-term maintenance of the MAT locus within the FOC are that (i) sexual reproduction may have been lost recently and independently throughout this complex and/or (ii) MAT genes may function in processes other than sexual reproduction. However, our working hypothesis is that MAT1-2 strains that are sexually compatible with the FOC clonal lineage may exist, but only MAT1-1 strains of this species have come in direct contact with humans, most likely through global trade in horticultural and agricultural commodities.

Consistent with prior genetic analyses of phytopathogenic members of the FOC (2) and human pathogenic fungi (15, 34), AFLPs appear to have identified greater genetic variation than our MLST data, with the exception of the two cyclamen-associated strains that possess a unique MLST haplotype. The clinical relevance of the AFLP genotypes of the clonal lineage, if any, remains to be determined, because they are currently not associated with a phenotype. Even though the present AFLP analyses were semiautomated, we strongly prefer MLST for epidemiological purposes because it provides a more direct estimate of nucleotide diversity by using electronically portable discrete DNA sequence data and because it is much less labor-intensive. The results of the present study also highlight the importance of identifying MLST loci that resolve species limits. Although partial sequences of the nuclear ribosomal large-subunit (28S) rDNA were recently purported to differentiate medically important fusaria (10), our MLST data clearly show that DNA sequences from the 28S rDNA and other commonly used loci, such as the nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region and the mtSSU rDNA, lack sufficient phylogenetic signal to resolve species boundaries among virtually all fusaria (19-22). As discovered for other clinically important fungi (reviewed in reference 32), we have found that single-copy nuclear genes interrupted by large and/or numerous introns such as EF-1α (7) are essential for developing a robust MLST typing scheme. Future development of high-resolution MLST genotyping of all medically and agriculturally important fusaria will be greatly accelerated by the availability of expressed-sequence tag and whole-genome sequence data (http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/fungi/fusarium/), thereby facilitating global epidemiology via the Internet (7, 12, 16, 33).

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are due Anastasia P. Litvintseva and Robert E. Marra (Duke University), Kelly Ivors and Tom Bruns (University of California, Berkeley), Stephen Rehner (BARC-USDA, Beltsville, Md.), and Ulrich Mueller (University of Texas, Austin) for generously sharing their AFLP expertise; the individuals and culture collections listed in Table 1 for supplying strains used in this study; Don Fraser for preparing the figures; and Amy Morgan for running DNA sequences used in this study on an ABI 3730 genetic analyzer and for synthesis of the primers.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anaissie, E. J., R. T. Kuchar, J. H. Rex, A. Francesconi, M. Kasai, F.-M. Müller, M. Lozano-Chiu, R. C. Summerbell, M. C. Dignani, S. J. Chanock, and T. J. Walsh. 2001. Fusariosis associated with pathogenic Fusarium species colonization of a hospital water system: a new paradigm for the epidemiology of opportunistic mold infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:1871-1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baayen, R. P., K. O'Donnell, P. J. M. Bonants, E. Cigelnik, L. P. N. M. Kroon, E. J. A. Roebroeck, and C. Waalwijk. 2000. Gene genealogies and AFLP analyses in the Fusarium oxysporum complex identify monophyletic and nonmonophyletic formae speciales causing wilt and rot diseases. Phytopathology 90:891-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boutati, E. I., and E. J. Anaissie. 1997. Fusarium, a significant emerging pathogen in patients with hematologic malignancy: ten years' experience at a cancer center and implications for management. Blood 90:999-1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carbone, I., J. B. Anderson, and L. M. Kohn. 1999. Patterns of descent in clonal lineages and their multilocus fingerprints are resolved with combined gene genealogies. Evolution 53:11-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Couch, B. C., and L. M. Kohn. 2000. Clonal spread of Sclerotium cepivorum in onion production with evidence of past recombination events. Phytopathology 90:514-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Pietro, A., M. P. Madrid, Z. Caracuel, J. Delgado-Jarana, and M. I. G. Roncero. 2003. Fusarium oxysporum: exploring the molecular arsenal of a vascular wilt pathogen. Mol. Plant Pathol. 4:315-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geiser, D. M., M. del M. Jiménez-Gasco, S. Kang, I. Makalowska, N. Veeraraghavan, T. J. Ward, N. Zang, G. A. Kuldau, and K. O'Donnell. 2004. FUSARIUM-ID v. 1.0: a DNA sequence database for identifying Fusarium. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 110:1-7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gräser, Y., J. Kühnisch, and W. Presber. 1999. Molecular markers reveal exclusively clonal reproduction in Trichophyton rubrum. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3713-3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halliday, C. L., and D. A. Carter. 2003. Clonal reproduction and limited dispersal in an environmental population of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii isolates from Australia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:703-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hennequin, C., E. Abachin, F. Symoens, V. Lavarde, G. Reboux, N. Nolard, and P. Berche. 1999. Identification of Fusarium species involved in human infections by 28S rRNA gene sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3586-3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hovmøoller, M. S., A. F. Justesen, and J. K. M. Brown. 2002. Clonality and long-distance migration of Puccinia striformis f. sp. tritici in North-West Europe. Plant Pathol. 51:24-32. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang, S., J. E. Ayers, E. D. DeWolf, D. M. Geiser, G. Kuldau, G. W. Moorman, E. Mullins, W. Uddin, J. C. Correll, G. Deckert, Y.-H. Lee, Y.-W. Lee, F. N. Martin, and K. Subbarao. 2002. The internet-based fungal pathogen database: a proposed model. Phytopathology 92:232-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koenig, R. L., R. C. Ploetz, and H. C. Kistler. 1997. Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense consists of a number of divergent and globally distributed clonal lineages. Phytopathology 87:915-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuchar, R. T. 1996. Isolation of Fusarium from hospital plumbing fixtures: implications for environmental health and patient care. M.S. thesis. The University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston.

- 15.Litvintseva, A. P., R. E. Marra, K. Nielsen, J. Heitman, R. Vilgalys, and T. G. Mitchell. 2003. Evidence of sexual reproduction among Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A isolates in sub-Saharan Africa. Eukaryot. Cell 2:1162-1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maiden, M. C. J., J. A. Bygraves, E. Feil, G. Morelli, J. E. Russell, R. Urwin, Q. Zhang, J. Zhou, R. Zurth, D. A. Caugant, I. M. Feavers, M. Achtman, and B. G. Spratt. 1998. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3140-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morehouse, E. A., T. Y. James, A. R. D. Ganley, R. Vilgalys, L. Berger, P. J. Murphy, and J. E. Longcore. 2003. Multilocus sequence typing suggests the chytrid pathogen of amphibians is a recently emerged clone. Mol. Ecol. 12:395-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nucci, M., and E. Anaissie. 2002. Cutaneous infection by Fusarium species in healthy and immunocompromised hosts: implications for diagnosis and management. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:909-920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Donnell, K. 2000. Molecular phylogeny of the Nectria haematococca-Fusarium solani species complex. Mycologia 92:919-938. [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Donnell, K., E. Cigelnik, and H. I. Nirenberg. 1998. Molecular systematics and phylogeography of the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex. Mycologia 90:465-493. [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Donnell, K., H. C. Kistler, E. Cigelnik, and R. C. Ploetz. 1998. Multiple evolutionary origins of the fungus causing Panama disease of banana: Concordant evidence from nuclear and mitochondrial gene genealogies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:2044-2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Donnell, K., H. C. Kistler, B. K. Tacke, and H. H. Casper. 2000. Gene genealogies reveal global phylogeographic structure and reproductive isolation among lineages of Fusarium graminearum, the fungus causing wheat scab. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:7905-7910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Donnell, K., T. J. Ward, D. M. Geiser, H. C. Kistler, and T. Aoki. 2004. Genealogical concordance between the mating type locus and seven other nuclear genes supports formal recognition on nine phylogenetically distinct species within the Fusarium graminearum clade. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41:600-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ortoneda, M., J. Guarro, M. P. Madrid, Z. Caracuel, M. I. G. Roncero, E. Mayayo, and A. Di Pietro. 2004. Fusarium oxysporum as multihost model for the genetic dissection of fungal virulence in plants and animals. Infect. Immun. 72:1760-1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raad, I., J. Tarrand, H. Hanna, M. Albitar, E. Janssen, M. Boktour, G. Bodey, M. Mardani, R. Hachem, D. Kontoyiannis, E. Whimbey, and R. Rolston. 2002. Epidemiology, molecular mycology, and environmental sources of Fusarium infection in patients with cancer. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 23:532-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skovgaard, K., H. I. Nirenberg, K. O'Donnell, and S. Rosendahl. 2001. Evolution of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum races inferred from multigene genealogies. Phytopathology 91:1231-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skovgaard, K., S. Rosendahl, K. O'Donnell, and H. I. Nirenberg. 2003. Fusarium commune is a new species identified by morphological and molecular phylogenetic data. Mycologia 95:630-636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swofford, D. L. 2002. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods), version 4. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Mass.

- 29.Tantaoui, A., M. Quinten, J.-P. Geiger, and D. Fernandez. 1996. Characterization of a single clonal lineage of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis causing Bayoud disease of date palm in Morocco. Phytopathology 86:787-792. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor, J. W., and M. C. Fisher. 2003. Fungal multilocus sequence typing—it's not just for bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:351-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor, J. W., D. M. Geiser, A. Burt, and V. Koufopanou. 1999. The evolutionary biology and population genetics underlying fungal stain typing. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:126-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor, J. W., D. J. Jacobson, S. Kroken, T. Kasuga, D. M. Geiser, D. S. Hibbett, and M. C. Fisher. 2000. Phylogenetic species recognition and species concepts in fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 31:21-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urwin, R., and M. C. J. Maiden. 2003. Multi-locus sequence typing: a tool for global epidemiology. Trends Microbiol. 11:479-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warris, A., C. H. W. Klaassen, J. F. G. M. Meis, M. T. de Ruiter, H. A. de Valk, T. G. Abrahamsen, P. Gaustad, and P. E. Verweij. 2003. Molecular epidemiology of Aspergillus fumigatus recovered from water, air, and patients shows two clusters of genetically distinct strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4101-4106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White, T. J., T. Bruns, S. Lee, and J. Taylor. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics, p. 313-322, In M. A. Innis, D. H. Gelfand, J. J. Sninsky, and T. J. White (ed.), PCR protocols, a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif.

- 36.Woudt, L. P., A. Neuvel, A. Sikkema, M. Q. J. M. van Grinsven, W. A. J. de Milliano, C. L. Campbell, and J. F. Leslie. 1995. Genetic variation in Fusarium oxysporum from cyclamen. Phytopathology 85:1348-1355. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu, J., and T. G. Mitchell. 2002. Strain variation and clonality in Candida spp. and Cryptococcus neoformans, p. 739-749. In R. A. Calderone and R. L. Cihlar (ed.), Fungal pathogenesis: principles and clinical applications. Marcel Dekker, New York, N.Y.

- 38.Yun, S.-H., T. Arie, I. Kaneko, O. C. Yoder, and B. G. Turgeon. 2000. Molecular organization of mating type loci in heterothallic, homothallic, and asexual Gibberella/Fusarium species. Fungal Genet. Biol. 31:7-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]