Abstract

A nucleotide transversion from guanine to uracil in the 23S rRNA confers linezolid resistance. We describe a real-time PCR using two Taqman probes that detects a single mutated allele among the genomes of Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis. Results were confirmed by a classical approach involving LabChip technology assayed with an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100.

Linezolid is an oxazolidinone that has excellent activity against many gram-positive bacteria (17, 18, 20, 22). Prevention of initiation complex formation in protein biosynthesis is assumed to be the mechanism of action (27). In vitro resistance to linezolid is mediated via mutations in the central region of domain V of 23S rRNA (12, 21, 33) and/or by as-yet-unknown mechanisms (24, 31). However, resistance in wild-type isolates of Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, and Streptococcus is conferred by a single nucleotide transversion from guanine to uracil at position 2576 in 23S rRNA (Escherichia coli numbering) (9, 10, 21, 29, 33). Isolates for which the MICs are ≥8 mg/liter are defined as resistant (6). Identification of the resistance genotype is complicated by the various numbers of 23S rRNA alleles among the genomes of these bacteria, for example, five copies in Staphylococcus aureus, four in Enterococcus faecalis, and six in Enterococcus faecium (2, 15, 19, 23). In vitro studies showed that one out of six mutated alleles in E. faecium and two out of four mutated alleles in E. faecalis were sufficient to confer linezolid resistance (14, 15). A correlation between the number of mutated alleles and the MIC was described for E. faecalis and E. faecium (14, 15). Homozygous susceptible or homozygous resistant isolates (all alleles mutated) can be detected by molecular tests, such as DNA sequencing of PCR-amplified fragments (14, 15, 25) or a restriction digestion following PCR amplification (15, 32). However, heterozygous linezolid-resistant isolates could be confirmed only by time-consuming and laborious methods (15). But these are exactly the isolates encountered in clinical practice: during linezolid therapy, primarily susceptible strains acquire resistance by stepwise mutation (1, 7, 8, 9) and probably by subsequent recombination (14). For rapid molecular detection and molecular confirmation of such isolates, we chose a 5′ nuclease real-time PCR assay with Taqman probes, a method which allows rapid, sensitive, and quantitative detection of single-nucleotide polymorphisms.

Seventy-two strains were included; 10 of them were linezolid resistant (MIC ≥ 8 μg/ml). They all emerged during linezolid therapy (one strain from the United States, E. faecium 3819 [8]; five from Austria, E. faecalis 3932 and E. faecium 3935, 3936, 3938, and 3939 [9]; and four from Germany isolated from a single patient, E. faecalis 3696 and 3697 and E. faecium 3695 and 3698 [E. Halle, J. Padberg, S. Rousseau, I. Klare, G. Werner, and W. Witte, Correspondence, Infection 32:182-183, 2004]). The 10 enterococcal strains were partly clonally related or identical (e.g., strains 3935, 3936, 3938, and 3939; strains 3695 and 3698; and strains 3696 and 3698 [data not shown]), but the linezolid MICs for them were different, suggesting a different number of mutated 23S alleles. The 62 linezolid-susceptible isolates (MICs of 0.5 to 2 μg/ml) were clonally diverse (data not shown). DNA extraction and purification were done using standard procedures and commercial kits (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), and DNA was quantified by fluorescence labeling (Pico Green kit; Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands). Classical PCR was performed with DNA beads (Amersham Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany). Real-time PCR was done with an ABI 7000 using a SYBR Green kit and a Taqman kit (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). The assay was first evaluated with primers 23S_TQF and 23S_TQR and the SYBR Green kit, and a 100 pM concentration of each primer and 1 ng of purified PCR product (later with 2 ng of genomic DNA) amplified in a classical approach with primers 23S_F and 23S_R were then added (Table 1). The specificity of products was confirmed by melting-curve analysis. The assay design was then applied to the Taqman kit system, including two labeled Taqman probes possessing 3′ MGB (minor groove binder) VIC-LIZ-TQ-S (detecting a wild-type or susceptible allele) and FAM-LIZ-TQ-R (detecting a mutated or resistant allele) probes (Table 1). Optimization included 5′ nuclease assays with various concentrations of primers (1, 10, and 100 pM), genomic DNA (0.066, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 ng), and probes (25, 50, 100, and 200 nM). An alternative FAM-LIZ-TQ-R probe was also tested (Table 1). All samples were assayed at least in triplicate.

TABLE 1.

Primers and probes used in this study

| Primer or probe | 5′ Sequencea | Temp (°C) | Size(s) (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23S_F | TGGGCACTGTCTCAACGA | 55 | 633, 634b | 29 |

| 23S_R | GGATAGGGACCGAACTGTCTC | |||

| 23S_TQF | ACCGAACTGTCTCACGACGTT | 60 | 72 | This study |

| 23S_TQR | CCCAAGGGTTGGGCTGTT | |||

| VIC-LIZ-TQ-S | VIC-CCCAGCTCGCGTGC-NFQ-MGB | This study | ||

| FAM-LIZ-TQ-R | FAM-AACCCAGCTAGCGTGC-NFQ-MGB | This study | ||

| 23S_1Rc | GGACGCTCTAGCCAGCTGAGC | 55 | 1,964 | This study |

| 23S_2Rc | GGCCTCTCGGACAACTCTCC | 55 | 1,272 | This study |

| 23S_3Rc | CCCTTCTTCAAGCTTATC | 55 | 1,286 | This study |

| 23S_4Rc | GTCAATCACTCAACTATGC | 55 | 1,756 | This study |

| ddl-EFM1 | GCAAGGCTTCTTAGAGA | |||

| ddl-EFM2 | CATCGTGTAAGCTAACTTC | 54 | 941 | 4 |

| ddl-EFC1 | ATCAAGTACAGTTAGTCTT | |||

| ddl-EFC2 | ACGATTCAAAGCTAACTG | 54 | 941 | 4 |

NFQ, nonfluorescent quencher; VIC and FAM, 5′-linked fluorescence labels (Applied Biosystems); MGB, minor groove binder.

The first size applies to E. faecalis; the second applies to E. faecium.

The forward primer is 23S_F.

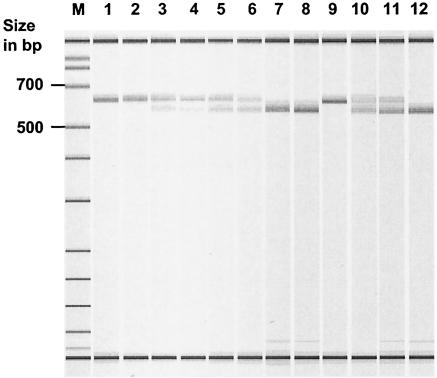

The nucleotide transversion G2576T in linezolid-resistant enterococci generates a new restriction endonuclease site recognized by enzymes like MaeI (C↓TAG) or NheI (G↓CTAGC) (mutated nucleotides are underlined) (15, 32). After endonuclease treatment, linezolid-susceptible enterococci still showed a nondigested fragment, and homozygous linezolid-resistant enterococci showed two fragments (however, a 43-bp fragment was not detectable) (Fig. 1). The band pattern in linezolid-resistant enterococci with a heterozygous genotype revealed three fragments (43 bp not detectable). Restriction was done with 5 μl of purified 23S_R-23S_F PCR product, 1× buffer, and 20 U of NheI at 37°C for 0.5 to 2 h. Separation of fragments was done with a 2% agarose gel and with a LabChip 1000 kit. LabChip technology requires a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany), allowing quick (3-min/sample) and easy-to-perform separation of DNA, RNA, or proteins in specialized microglass capillary chips. Each lane possesses two internal standards which are scaled to the external standard running on each chip. Inherent BioSizing software automatically calculates the size and quantity of each fragment in relation to the internal and external standards (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

FIG. 1.

Detection of 23S alleles of linezolid-resistant E. faecium and E. faecalis isolates by NheI digestion of purified pooled PCR fragments and subsequent separation in a LabChip 1000 measured in an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. The lowest and highest bands correspond to internal size markers. Lanes: M, external size markers; 1, E. faecium ATCC 19434; 2, E. faecium 3698; 3, E. faecium 3695; 4, E. faecium 3819; 5, E. faecium 3936; 6, E. faecium 3938; 7, E. faecium 3935; 8, E. faecium 3939; 9, E. faecalis V583; 10, E. faecalis 3932; 11, E. faecalis 3697; 12, E. faecalis 3696.

TABLE 2.

Results of NheI-digested 23S ribosomal DNA-pooled PCR products resolved with LabChip 1000 technology in an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100

| Lane in Fig. 1 | Isolate | Linezolid MIC (mg/liter) | Peak no.a | Size (bp) | Peak size | Concn (nmol/liter) | Ratio of mutated to wild-type isolatesb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | E. faecium ATCC 19434 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |||

| 3 | 630 | 31.24 | 3.42 | 6 | |||

| 2 | E. faecium 3698 | 8 | 2 | 587 | 3.66 | 0.49 | 1 |

| 3 | 636 | 27.23 | 3.34 | 5 | |||

| 3 | E. faecium 3695 | 32 | 2 | 587 | 8.37 | 0.96 | 2 |

| 3 | 638 | 19.67 | 2.08 | 4 | |||

| 4 | E. faecium 3819 | 16 | 2 | 585 | 7.84 | 0.88 | 2 |

| 3 | 635 | 22.53 | 2.33 | 4 | |||

| 5 | E. faecium 3936 | 16 | 2 | 584 | 11.43 | 1.63 | 3 |

| 3 | 636 | 18.73 | 2.45 | 3 | |||

| 6 | E. faecium 3938 | 32 | 2 | 583 | 10.55 | 1.49 | 3 |

| 3 | 633 | 13.59 | 1.77 | 3 | |||

| 7 | E. faecium 3935 | 32 | 2 | 585 | 29.87 | 3.37 | 6 |

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| 8 | E. faecium 3939 | 64 | 2 | 581 | 34.27 | 4.13 | 6 |

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| 9 | E. faecalis V583 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |||

| 3 | 623 | 33.06 | 3.37 | 4 | |||

| 10 | E. faecalis 3932 | 32 | 2 | 585 | 16.06 | 1.63 | 3 |

| 3 | 631 | 4.87 | 0.46 | 1 | |||

| 11 | E. faecalis 3697 | 16 | 2 | 582 | 19.38 | 2.05 | 3 |

| 3 | 631 | 13.67 | 1.33 | 1 | |||

| 12 | E. faecalis 3696 | 32 | 2 | 576 | 25.18 | 3.39 | 4 |

| 3 | 0 |

Peaks 1 and 4 were identified for all lanes (internal markers) and are not included.

Based on a comparison of peak areas. The number is the result of three independent experiments; here the data for a single experiment are given.

Selection of strains.

Data for the 10 linezolid-resistant isolates (seven E. faecium and three E. faecalis isolates) are given in Table 2. The species was confirmed by using ddI-specific primer pairs (4) (Table 1). The 23S rRNA alleles were amplified classically by using genomic DNA and primers 23S_F and 23S_R. Digestion with NheI identified two E. faecium isolates (3935 and 3939) and a single E. faecalis isolate (3696) with all 23S alleles mutated (Fig. 1; see text below for details).

Taqman PCR.

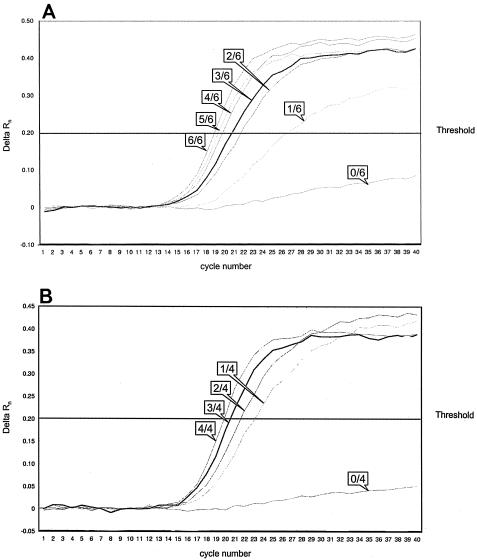

Homozygous linezolid-susceptible and -resistant isolates, including E. faecium ATCC 19434 (susceptible), E. faecium 3939 (resistant), E. faecalis V583 (susceptible), and E. faecalis 3696 (resistant; see also above), were chosen to establish a 5′ nuclease assay. Primer concentrations of 100 pM each and concentrations of 25 nM for the probe FAM-LIZ-TQ-R, detecting the resistant allele, and 100 nM for the probe VIC-LIZ-TQ-S, detecting the susceptible allele, led to the best results (data not shown in detail). An alternative probe detecting the resistant allele did not perform better (data not shown). As a threshold for all experiments, a value of 0.2 could be assigned: all nonspecific signals were beneath this value, and all specific signals were above it. Based on these results, gene dosage experiments were performed as follows. Genomic DNA from homozygous linezolid-susceptible and -resistant test isolates (E. faecium and E. faecalis) was quantified and mixed in a manner simulating DNA from wild-type isolates. All possible ratios of wild-type to mutated alleles were covered (for E. faecalis, 0:4, 1:3, 2:2, 3:1, and 4:0; for E. faecium, 0:6, 1:5, 2:4, 3:3, 4:2, 5:1, and 6:0). Existence of the appropriate alleles was precisely detected by the corresponding probes, which means that a single mutated allele was detected among four in E. faecalis and among six in E. faecium (Fig. 2). Detection with the FAM-labeled probe revealed that the change in the δ CT value was smaller the more alleles had mutated (Fig. 2). Similarly, when using the VIC-labeled probe, the change in the δCT value was smaller the less alleles had mutated (data not shown). However, even under optimized test conditions, the exact number of mutated versus wild-type alleles could not be quantitated. Nevertheless, the definite detection of a single mutated allele convinced us to prove the test scheme with wild-type isolates. All 72 isolates were investigated by using the approach described above (data not shown). All 10 linezolid-resistant isolates were precisely identified, allowing differentiation between isolates of homozygous and heterozygous linezolid resistance genotypes based on a signal from one or both of the Taqman probes used (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Detection of the G or T allele type of 23S ribosomal DNA by real-time PCR using two labeled probes. In vitro gene dosage experiments vary the number of wild-type versus mutated alleles in E. faecium (A) and E. faecalis (B) (see text for details). Only results for the FAM-LIZ-TQ-R probe are shown. For better visibility, only one representative per allele mix is shown. Labels indicate the numbers of mutated alleles relative to the overall number of 23S ribosomal DNA copies per genome (E. faecium, 6; E. faecalis, 4). Delta Rn, difference of fluorescence signals of a given template and the no-template control.

Classical approach.

We analyzed PCR products amplifying 23S rRNA alleles (primers 23S_F and 23S_R) from our 10 linezolid-resistant enterococci digested with NheI (Fig. 1) (for details, see above). Quantitative evaluation based on LabChip technology and BioSizing software revealed a distribution of allele types in heterozygous enterococci based on calculated molarities of the corresponding bands (Fig. 1 and Table 2). The results have been confirmed by three independent experiments. The genome of E. faecalis V583 has been released, which allowed us to establish a verification test based on a separate amplification of all four 23S alleles followed by a subsequent confirmation of the corresponding allele type (G or T) by Taqman PCR (Table 1). The four PCRs were successfully applied to our test isolates (3932 and 3697), a homozygous susceptible E. faecalis isolate (V583), and a homozygous resistant E. faecalis isolate (3696). PCR products were purified, quantified, and subjected to Taqman PCR. Each Taqman PCR showed a signal only with a single probe, suggesting a homozygous type for the four PCRs per isolate (data not shown). Calculations made with BioSizing software were confirmed as follows: in E. faecalis 3932, alleles 1, 3, and 4 showed a G-to-T mutation, whereas in E. faecalis 3697, alleles 1, 2, and 4 were mutated (3696 possessed only T-type alleles; V583 possessed only G-type alleles).

A 5′ nuclease assay using Taqman probes is a modern, time-saving PCR technique allowing online detection and quantification of amplified DNA (5, 11). Usage of distinctly designed probes, including an MGB motif, enables detection of single DNA nucleotide polymorphisms with great specificity and sensitivity. This is useful, for example, for detecting resistance characters based on single nucleotide polymorphisms such as fluoroquinolone or rifampin resistance (13, 28, 30). Even more sophisticated is the molecular detection of linezolid resistance, in which in Staphylococcus and Enterococcus, four to six gene copies code for 23S rRNA targeted by this antibiotic. Woodford and coworkers (32) described a real-time PCR using LightCycler technology, which is different from Taqman technology (two probes per allele versus one probe per allele; sustaining of probes in LightCycler technology versus degradation of probes during Taqman PCR). Mutated and wild-type alleles were detected by a single probe and distinguished by different melting curves (32). This assay design cannot be applied to other real-time PCR cyclers. We established a Taqman assay using two probes differing by a single nucleotide. Both probes are independently and in combination capable of detecting the susceptible and resistant allele types. The probes did not show any cross-hybridization: there were no nonspecific signals for the opposite allele types (Fig. 2). Our assay detected a single mutated 23S allele among four to six copies in the genomes of E. faecalis and E. faecium in vitro and in the in vivo-generated resistant isolates. This detection allows prediction of future linezolid resistance during therapy even before it is detected phenotypically, since a mutation in a single 23S allele might not in all cases be sufficient to confer linezolid nonsusceptibility (14, 15). The findings for E. faecium 3698 demonstrated that even in clinical practice, a single mutated allele is capable of mediating linezolid resistance (MIC, 8 μg/ml). There is reasonable concern whether such isolates would be unambiguously identified by melting-curve analysis after real-time PCR using the LightCycler (32) or by sequencing pooled PCR products of all 23S alleles (15).

In conclusion, we established a Taqman PCR assay with two labeled probes detecting linezolid-resistant and -susceptible 23S alleles. Our assay design could easily be applied to other genera, like Staphylococcus, but slightly different oligonucleotides would have to be used (e.g., for S. aureus, one nucleotide mismatch for the two probes). With the help of LabChip technology, we were able to address the expected number of mutated alleles, which correlated well with the corresponding linezolid MICs for E. faecalis, E. faecium, and S. aureus (14, 15; T. A. Wichelhaus, S. Besier, V. Brade, and A. Ludwig, abstr. KMP021 from the 55th Annu. Mtg. of the DGHM, Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 293[Suppl. 36]:375-376, 2003) (Table 2). This result illustrates again that modern techniques like multiplex PCR, real-time PCR, and DNA chip technology are appropriate tools to predict and/or confirm corresponding resistance phenotypes (3, 16, 26).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge skillful technical assistance by Bianca Hildebrandt and Carola Konstabel. We thank R. Patel, F. J. Allerberger, and E. Halle for providing the linezolid-resistant strains for our analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Auckland, C., L. Teare, F. Cooke, M. E. Kaufmann, M. Warner, G. Jones, K. Bamford, H. Ayles, and A. P. Johnson. 2002. Linezolid-resistant enterococci: report of the first isolates in the United Kingdom. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:743-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba, T., F. Takeuchi, M. Kuroda, H. Yuzawa, K. Aoki, A. Oguchi, Y. Nagai, N. Iwama, K. Asano, T. Naimi, H. Kuroda, L. Cui, K. Yamamoto, and K. Hiramatsu. 2002. Genome and virulence determinants of high virulence community-acquired MRSA. Lancet 359:1819-1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Call, D. R., M. K. Bakko, M. J. Krug, and M. C. Roberts. 2003. Identifying antimicrobial resistance genes with DNA microarrays. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3290-3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutka-Malen, S., S. Evers, and P. Courvalin. 1995. Detection of glycopeptide resistance genotypes and identification to the species level of clinically relevant enterococci by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:24-27. (Erratum, 33:1434.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellerbrok, H., H. Nattermann, M. Oezel, L. Beutin, B. Appel, G. Pauli. 2002. Rapid and sensitive identification of pathogenic and apathogenic Bacillus anthracis by real-time PCR. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 214:51-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID). 2001. Linezolid breakpoints. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 7:283-284.11422259 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzales, R. D., P. C. Schreckenberger, M. B. Graham, S. Kelkar, K. DenBesten, and J. P. Quinn. 2001. Infections due to vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium resistant to linezolid. Lancet 357:1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrero, I. A., N. C. Issa, and R. Patel. 2002. Nosocomial spread of linezolid-resistant, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. N. Engl. J. Med. 346:867-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson, A. P., L. Tysall, M. W. Stockdale, N. Woodford, M. E. Kaufmann, M. Warner, D. M. Livermore, F. Asboth, and F. J. Allerberger. 2002. Emerging linezolid-resistant Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium isolated from two Austrian patients in the same intensive care unit. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 21:751-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones, R. N., P. Della-Latta, L. V. Lee, Douglas, and J. Biedenbach. 2002. Linezolid-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolated from a patient without prior exposure to an oxazolidinone: report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 42:137-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein, D. 2002. Quantification using real-time PCR technology: applications and limitations. Trends Mol. Med. 8:257-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kloss, P., L. Xiong, and D. L. Shinabarger. 1999. Resistance mutations in 23S rRNA identify the site of action of the protein synthesis inhibitor linezolid in the ribosomal peptidyl transferase center. J. Mol. Biol. 294:93-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lapierre, P., A. Huletsky, V. Fortin, F. J. Picard, P. H. Roy, M. Ouellette, and M. G. Bergeron. 2003. Real-time PCR assay for detection of fluoroquinolone resistance associated with grlA mutations in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3246-3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lobritz, M., R. Hutton-Thomas, S. Marshall, and L. B. Rice. 2003. Recombination proficiency influences frequency and locus of mutational resistance to linezolid in Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3318-3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall, S. H., C. J. Donskey, R. Hutton-Thomas, R. A. Salata, and L. B. Rice. 2002. Gene dosage and linezolid resistance in Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3334-3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monecke, S., I. Leube, and R. Ehricht. 2003. Simple and robust array-based methods for the parallel detection of resistance genes of Staphylococcus aureus. Genome Lett. 2:106-118. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mutnick, A. H., V. Enne, and R. N. Jones. 2003. Linezolid resistance since 2001: SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. Ann. Pharmacother. 37:769-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noskin, G. A., F. Siddiqui, V. Stosor, D. Hacek, and L. R. Peterson. 1999. In vitro activities of linezolid against important gram-positive bacterial pathogens including vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2059-2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paulsen, I. T., L. Banerjei, G. S. A. Myers, K. E. Nelson, R. Seshadri, T. D. Read, D. E. Fouts, J. A. Eisen, S. R. Gill, J. F. Heidelberg, H. Tettelin, R. J. Dodson, L. Umayam, L. Brinkac, M. Beanan, S. Daugherty, R. T. DeBoy, S. Durkin, J. Kolonay, R. Madupu, W. Nelson, J. Vamathevan, B. Tran, J. Upton, T. Hansen, J. Shetty, H. Khouri, T. Utterback, D. Radune, K. A. Ketchum, B. A. Dougherty, and C. M. Fraser. 2003. Role of mobile DNA in the evolution of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Science 299:2071-2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perry, C. M., and B. Jarvis. 2001. Linezolid—a review of its use in the management of serious gram-positive infections. Drugs 61:525-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prystowsky, J., F. Siddiqui, J. Chosay, D. L. Shinabarger, J. Millichap, L. R. Peterson, and G. A. Noskin. 2001. Resistance to linezolid: characterization of mutations in rRNA and comparison of their occurrences in vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2154-2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubinstein, E., S. K. Cammarata, T. H. Oliphant, R. G. Wunderink, and the Linezolid Nosocomial Pneumonia Study Group. 2001. Linezolid (PNU-100766) versus vancomycin in the treatment of hospitalized patients with nosocomial pneumonia: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:402-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruggero, K. A., L. K. Schroeder, P. C. Schreckenberger, A. S. Mankin, and J. P. Quinn. 2003. Nosocomial superinfections due to linezolid-resistant Enterococcus faecalis: evidence for a gene dosage effect on linezolid MICs. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 47:511-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sander, P., L. Belova, Y. G. Kidan, P. Pfister, A. S. Mankin, and E. C. Böttger. 2002. Ribosomal and non-ribosomal resistance to oxazolidinones: species-specific idiosyncrasy of ribosomal alterations. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1295-1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinclair, A., C. Arnold, and N. Woodford. 2003. Rapid detection and estimation by pyrosequencing of 23S rRNA genes with a single nucleotide polymorphism conferring linezolid resistance in enterococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3620-3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strommenger, B., C. Kettlitz, G. Werner, and W. Witte. 2003. Multiplex PCR assay for simultaneous detection of nine clinically relevant antibiotic resistance genes in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4089-4094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swaney, S. M., H. Aoki, M. C. Ganoza, and D. L. Shinabarger. 1998. The oxazolidinone linezolid inhibits initiation of protein synthesis in bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:3251-3255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torres, M. J., A. Criado, M. Ruiz, A. C. Llanos, J. C. Palomares, and J. Aznar. 2003. Improved real-time PCR for rapid detection of rifampin and isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 45:207-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsiodras, S., H. S. Gold, G. Sakoulas, G. M. Eliopoulos, C. Wennersten, L. Venkataraman, R. C. Moellering, and M. J. Ferraro. 2001. Linezolid resistance in a clinical isolate of Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 358:207-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker, R. A., N. Saunders, A. J. Lawson, E. A. Lindsay, M. Dassama, L. R. Ward, M. J. Woodward, R. H. Davies, E. Liebana, and E. J. Threlfall. 2001. Use of a LightCycler gyrA mutation assay for rapid identification of mutations conferring decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin in multiresistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1443-1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willems, R. J., J. Top, D. J. Smith, D. I. Roper, S. E. North, and N. Woodford. 2003. Mutations in the DNA mismatch repair proteins MutS and MutL of oxazolidinone-resistant or -susceptible Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3061-3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woodford, N., L. Tysall, C. Auckland, M. W. Stockdale, A. J. Lawson, R. A. Walker, and D. M. Livermore. 2002. Detection of oxazolidinone-resistant Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium strains by real-time PCR and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4298-4300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiong, L., P. Kloss, S. Douthwaite, N. M. Andersen, S. Swaney, D. L. Shinabarger, and A. S. Mankin. 2000. Oxazolidinone resistance mutations in 23S rRNA of Escherichia coli reveal the central region of domain V as the primary site of drug action. J. Bacteriol. 182:5325-5331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]