Abstract

Antibodies to Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) nonstructural 1 (NS1) protein constitute a marker of natural JEV infection among populations vaccinated with inactivated JE vaccine. In Japan, with few recent human JE cases, the natural infection rate is critical to evaluate the necessity of continuing JE vaccination. A sensitive immunochemical staining method for detecting NS1 antibodies in individuals naturally and subclinically infected with JEV was previously established. Here, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect NS1 antibodies in equine sera was developed and evaluated as an alternative to immunostaining. By this method, NS1 antigens contained in culture fluids from cells stably transfected with the NS1 and NS2A genes were captured by a rabbit anti-NS1 polyclonal antibody. Three nanograms per well of NS1 antigen, corresponding to 1:2 to 1:8 dilutions of the culture fluid, was sufficient for testing. ELISA values were obtained by a single-serum dilution (1:100), which correlated with ELISA titers obtained by an endpoint method. Under a tentative cutoff value (0.122) statistically calculated from NS1 antibody levels of horses in an area where JEV is not endemic, a high level of qualitative agreement (85.3%) was obtained between the ELISA and immunostaining methods. A significant correlation coefficient (0.799; P < 0.001) was also obtained between the two methods. Three experimentally infected horses seroconverted no later than 13 to 23 days postinfection, whereas 4 field horses infected during an epizootic remained positive for NS1 antibodies for at least 40 weeks. Our results indicate that the ELISA used here was sufficiently sensitive to detect subclinical infections in vaccinated equine populations.

Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) is a member of the genus Flavivirus in the family Flaviviridae (4). In a paradomestic environment, the virus is maintained in a transmission cycle between amplifier swine and vector mosquitoes (26). Humans are infected by bites from infectious mosquitoes and subsequently develop neurological diseases at subclinical:clinical ratios of 25:1 to 1,000:1 (31). This virus is distributed in many areas of Asia and parts of Oceania, with 50,000 human cases and 10,000 deaths per year reported (5). In Japan, several thousand human Japanese encephalitis (JE) cases were reported annually prior to the mid-1960s (8). However, a national JE vaccination program has successfully controlled the disease, keeping the annual number of confirmed human cases to fewer than 10 during the last decade (28).

Horses are also susceptible to JEV. Although most infective mosquito bites result in subclinical infections, some infected horses develop fatal encephalitis, similar to humans. Large epizootics producing several thousands of equine JE cases in a single year were reported during the 1930s and 1940s (6). Following the introduction of inactivated JE vaccine in 1948, the number of reported cases decreased markedly (22). In recent years, racehorses, which have a substantial economic value, have been vaccinated every year prior to the epizootic season in Japan. No JE cases have been reported in racehorses since 1986 (19).

The recent reduction in human and equine JE cases following vaccination indicates that vaccination has contributed to the control of JE (9). On the other hand, the reduction in JE cases might also have been the result, or at least in part, of less contact with infected mosquitoes (8). The use of insecticides and improved irrigation schemes for rice cultivation has reduced the number of vector mosquitoes. In addition, the structure and locations of pigpens have been changed so that pigs are now less frequently exposed to mosquito bites.

As a result of these changes in Japan, concerns about side effects from the inactivated JE vaccine (1, 3, 23) have caused some to question the necessity of continuing vaccination. The most reliable strategy to address this question is to investigate how often humans and equines acquire natural JEV infections. Unfortunately, it has been difficult to obtain natural infection rates among vaccinated populations by conventional serologic methods, such as neutralization and hemagglutination-inhibiting (HAI) tests, since these methods are not capable of differentiating antibodies induced by natural infection from those induced by vaccination.

A sensitive method based on immunochemical staining for the detection of antibodies to nonstructural 1 (NS1) protein of JEV has been established (14). Individuals vaccinated with inactivated JE vaccine consisting of viral structural proteins develop antibodies only to the structural proteins, whereas infection causes development of antibodies to nonstructural proteins in addition to antibodies to structural proteins. Therefore, detection of NS1 antibodies can identify naturally infected individuals among vaccinated populations. By this technique, a small-scale survey revealed relatively high annual infection rates in humans (5 to 10%) (14) and equines (15 to 67%) (13). Based on these results, it seemed desirable to carry out a larger-scale survey to show more clearly the situation in respect to exposure of humans and equines to natural infection with JEV.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is simpler than immunostaining and more suitable for larger-scale surveys. However, ELISA has appeared less sensitive; while previous results showed that ELISA could detect NS1 antibody levels induced in sera of clinical cases, those of subclinical infections were not detected (27). For this reason, an original immunostaining method that could be used instead of ELISA was previously developed (14). In the present study, we develop an ELISA method that is equally as sensitive as the earlier immunostaining method for detecting NS1 antibodies in horse sera.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibody production.

Monoclonal antibodies to JEV NS1 antigens were generated, based on a method previously described for generating monoclonal antibodies to different antigens (10, 15). Briefly, BALB/c mice were immunized repeatedly with lysates of cells stably producing NS1 antigen (ME4 clone) (14), followed by fusion of the mouse spleen cells with the myeloma cell line P3U1. Hybridoma cells were screened for production of NS1 antibodies by ELISA (see below) and cloned twice by limiting dilution. An antibody, 2D5, that specifically reacted with JEV NS1 as determined by immunoprecipitation (see below) and Western blotting analyses (data not shown) was used for the present study. Rabbit anti-NS1 hyperimmune serum was obtained by repeated immunization of a Japanese white rabbit with affinity-purified NS1 obtained from culture fluids of JEV-infected Vero cells (see below).

Plasmid construction.

The JEV cDNA encoding the signal sequence of NS1, NS1, and NS2A was amplified by PCR with the template plasmid, PM6 (21), which contains cDNA from the middle of the E gene through the NS1 and NS2A genes to the middle of the NS3 gene, i.e., nucleotides 1,722 to 4,857 (where 1 is the first nucleotide of the C protein initiation codon). The sense primer, 5′-CCCGAATTCACCATGGCTTTGGCCTTCTTAGCCACA-3′, included an EcoRI site, an efficient eukaryotic initiation site (16), and a start codon, followed by the codons encoding Ala-Leu-Ala-Phe-Leu-Ala-Thr of the NS1 signal sequence. The antisense primer, 5′-GGCTCTAGATTATCTCTTCTTGTTTGGGTT-3′, contained the C-terminal six codons of NS2A, the adjacent termination codon, and an XbaI site. The amplified cDNA was inserted into the pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.) at the EcoRI/XbaI site between the strong eukaryotic promoter derived from human cytomegalovirus and the polyadenylation signal derived from bovine growth hormone. The construct was designated pcJENS1NS2A. Proper insertion of the gene cassette in pcJENS1NS2A was confirmed by sequencing. The plasmid DNA was purified by a standard polyethylene glycol precipitation method (2).

Transfection and selection of transfected cells.

Cell clones stably transfected with pcJENS1NS2A were generated, following a method previously described for generating a cell line continuously expressing JEV E antigen (11). Briefly, CHO-K1 cells were transfected with 1.0 μg of pcJENS1NS2A with Lipofectamine-Plus (Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, Md.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following selection with medium supplemented with G418 (Invitrogen) at a concentration of 400 μg/ml, transfected cells displaying high-level NS1 protein expression were selected by limiting-dilution cloning and immunostaining with a monoclonal antibody specific for NS1 (2D5).

ELISA for quantification of NS1 antigen.

NS1 antigen in culture fluids of cells stably transfected with pcJENS1NS2A was quantified by a sandwich ELISA, based on a method used for quantifying JEV E antigen (11). Briefly, 96-well microplates (Maxisorp; A/S Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) sensitized with rabbit anti-NS1 hyperimmune sera were incubated serially with test samples, a monoclonal antibody to NS1 (2D5), alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Zymed, San Francisco, Calif.), and p-nitrophenyl phosphate. Antigen levels were calculated from absorbance values obtained with the sample and a reference standard and were expressed as the amount of NS1 protein in nanograms per milliliter. The reference standard was prepared with affinity-purified NS1 obtained from culture fluids of JEV-infected Vero cells with 2D5 antibody, and the NS1 protein amount contained in the standard NS1 preparation was estimated by comparison with bovine serum albumin (BSA) samples in silver-stained gels.

Immunoprecipitation and affinity purification.

NS1 antigen contained in culture fluids of stably transfected cells was immunoprecipitated with a monoclonal antibody to NS1 (2D5) coupled to Sepharose 4B beads (NHS [N-hydroxysuccinimide]-activated Sepharose 4B Fast Flow; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the instructions supplied by the manufacturer. The precipitated proteins were heated at 100°C for 2 min or unheated under nonreducing conditions and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by detection by silver staining (Silver staining kit; Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.).

JEV NS1 protein was affinity purified from culture fluids of JEV-infected Vero cells by incubation with 2D5 antibody coupled to Sepharose 4B beads, followed by elution with 0.2 M glycine buffer (pH 3.0). The eluted NS1 was immediately neutralized with a small amount of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 9.0). The purity of NS1 (>95% of the total protein) was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

ELISA for quantifying NS1 antibodies in horse sera.

A conventional ELISA using captured antigen was performed for quantifying antibodies to JEV NS1. Microplates (Maxisorp) were sensitized by incubation at 4°C overnight with rabbit anti-NS1 hyperimmune sera diluted 1:10,000 in 0.1 M sodium carbonate buffer (pH 9.6), followed by blocking at 37°C for 30 min with blocking reagent and incubation at 37°C for 1 h with culture fluids of cells stably transfected with pcJENS1NS2A. The blocking reagent was phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20, 1% BSA, and 2% casein (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, Mo.). The amount of NS1 antigen was adjusted to 3 ng/well, which corresponded to 1:2 to 1:8 dilutions of the culture fluids. Sensitized plates were incubated serially with test sera at a 1:100 dilution, alkaline phosphatase-conjugated affinity-purified rabbit anti-horse IgG (Fc specific; Rockland, Gilbertsville, Pa.) was incubated at a 1:1,000 dilution, and p-nitrophenyl phosphate was incubated at 1 mg/ml. The blocking reagent was used as a diluent for culture fluid, test sera, and the conjugate. Tests were done in duplicate.

To eliminate nonspecific reactions, a nonsensitized control plate that used the blocking reagent in place of antigen-containing culture fluids was run in parallel. The difference between absorbances obtained with antigen-sensitized and nonsensitized wells was regarded as reaction specific for NS1. To minimize interplate variations, a constant positive-control serum pooled from several positive samples was included in every plate, and absorbances obtained with test samples were adjusted with the value for the positive control as 0.5. The adjusted absorbances were expressed as ELISA values.

Serum samples.

Most sera in the present study were the same as those used in a previous survey of NS1 antibodies among horses by the immunostaining method (13), and so their NS1 antibody titers were known. All sera were collected from thoroughbred horses. Negative-control sera used for determination of the cutoff value differentiating positive from negative samples were obtained from 46 yearlings that had been born and kept in Hokkaido (a area of northern Japan where JE is not endemic) without vaccination with JE vaccine. These controls were negative for HAI antibody and NS1 antibody by the immunostaining method (13).

Sera from 2-year-old racehorses were collected at seven racetracks in Japan from 1998 through 2000. Sera from three experimentally infected horses were obtained by inoculating 1- to 3-year-old horses intramuscularly with 1 × 106 to 4 × 108 PFU of the AT31 strain of JEV (29), followed by euthanization 13 to 23 days after infection. Four naturally and subclinically infected horses were selected from a horse population in which most individuals showed seroconversion during a limited period in an epizootic season, 1982, in Tochigi Prefecture, eastern Japan.

All animal experiments were conducted according to the Guidelines for Animal Experimentation at the Equine Research Institute, Tochigi, Japan.

Statistical analysis.

Calculations of correlation coefficients and evaluations of statistical significance were done with Microsoft Excel 2002.

RESULTS

Generation of a stable cell line producing extracellular NS1 antigen.

An earlier study generated CHO cells stably transfected with a plasmid containing only the NS1 gene (designated pcJENS1), using intracellular NS1 antigens for the immunostaining method to quantify NS1 antibodies (14). However, an elongated form of NS1 (NS1′), which is produced in JEV-infected mammalian cells (20), can be produced by expression of the NS1 and NS2A genes (12). To obtain NS1 antigen suited for ELISA in the present study, we constructed CHO cells stably transfected with a plasmid containing the NS1 and NS2A genes (pcJENS1NS2A) and compared them with pcJENS1-transfected cells for their ability to produce extracellular NS1 antigens.

CHO cells were transfected with pcJENS1NS2A and selected in G418-containing medium. Although only 5% of cells expressed NS1 antigen after seven passages in G418-containing medium, one limiting-dilution cloning step increased the percentage of NS1-expressing cells to 95 to 100%. Several clones containing NS1-expressing cells at high percentages were then compared for levels of extracellular NS1 antigen production. The clone 3G8, which had the highest NS1 antigen level in culture fluid, was used for subsequent experiments. When 3G8 cells were grown to form, the monolayers were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline and maintained in minimal essential medium containing 0.1% BSA for 24 h, and the level of NS1 antigen released from 3G8 cells ranged from 70 to 250 ng/ml with a mean of 133 ng/ml as determined by sandwich ELISA.

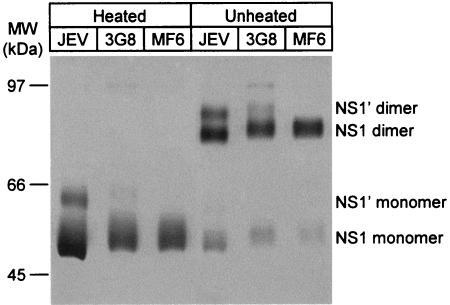

Next, we analyzed NS1 antigens released from 3G8 cells by immunoprecipitation, comparing them to NS1 antigens released from Vero cells infected with JEV or MF6 cells (Fig. 1). The MF6 clone was the highest extracellular NS1 producer among several cell clones stably transfected with pcJENS1. While MF6 cells produced only NS1, both NS1 and NS1′ were produced by 3G8 cells, similar to those produced by JEV-infected cells. The dimeric forms of NS1 or NS1′ shown in unheated samples appeared in monomer form in heated samples. The relatively broad band observed in the results shown in Fig. 1 probably reflects heterogeneity in glycosylation of the NS1 and NS1′ proteins. Although authentic NS1 molecules produced by JEV-infected Vero cells migrated slightly faster than those produced by CHO-derived 3G8 or MF6 cells, digestion of these samples with peptide-N-glycosidase F showed equivalent molecular sizes for each NS1 protein (data not shown). These results indicate that authentic processing of NS1 and NS1′ occurred in 3G8 cells, and we decided to use 3G8 cells for production of the NS1 antigen used for ELISA for quantification of NS1 antibodies.

FIG. 1.

Immunoprecipitation of culture fluids from Vero cells infected with JEV and CHO cells transfected with pcJENS1NS2A (3G8 cells) or pcJENS1 (MF6 cells) with a monoclonal antibody to NS1 (2D5). Samples heated or unheated under nonreduced conditions were run on an 8.5% polyacrylamide gel and detected by silver staining.

Determination of antigen amount for ELISA.

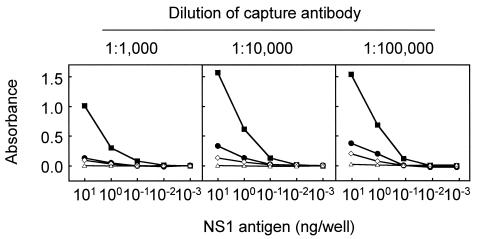

To determine basic conditions for ELISA, we first examined concentrations of the capture antibody and NS1 antigen used for sensitization of microplates (Fig. 2). Three dilutions of rabbit anti-NS1 hyperimmune serum ranging from 1:1,000 to 1:100,000 and five dilutions of 3G8 cell culture fluid containing 0.01 to 100 ng of NS1 antigen per ml (corresponding to 0.001 to 10 ng/well) were used for comparison. Three positive and one negative horse serum samples as determined by immunostaining were used for this evaluation: the positive samples showed high, moderate, and low absorbances, respectively, in a preliminary ELISA for NS1 antibody detection.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of ELISA reactions obtained with 3 dilutions of capture antibody (rabbit anti-NS1 hyperimmune serum) and 5 dilutions of 3G8 cell culture fluid containing 0.01 to 100 ng of NS1 antigen per ml (corresponding to 0.001 to 10 ng/well) and with highly positive (solid squares), moderately positive (solid circles), low-positive (open diamonds), and negative (open triangles) sera.

For the capture antibody, the dilutions of 1:10,000 and 1:100,000 provided similar absorbance curves for each of four sera. However, considering the capacity of a microplate to bind IgG molecules (approximately 400 ng/well) and the concentration of IgG in rabbit serum (approximately 10 mg/ml), we decided to use a dilution of 1:10,000, which corresponds to 100 ng of IgG per well.

For antigen concentration, the highest absorbances in any serum were shown at 10 ng/well, as expected. The ratios of absorbances obtained with moderately positive, low-positive, and negative sera to that obtained with highly positive serum were equivalent under conditions of 10 and 1 ng/well. An experiment to measure unbound NS1 antigens showed that an average of 17 ng was recovered from wells that were first sensitized with rabbit anti-NS1 hyperimmune serum at a dilution of 1:10,000 and then incubated with 20 ng of antigen overnight at 4°C or for 1 h at 37°C (data not shown). Therefore, we decided to use 3 ng of NS1 antigen per well for the assay. Since the culture fluid of 3G8 cells contained NS1 antigen at 70 to 250 ng/ml, culture fluid was diluted approximately 1:2 to 1:8 to obtain this amount (3 ng/well).

Dilution factor of test sera.

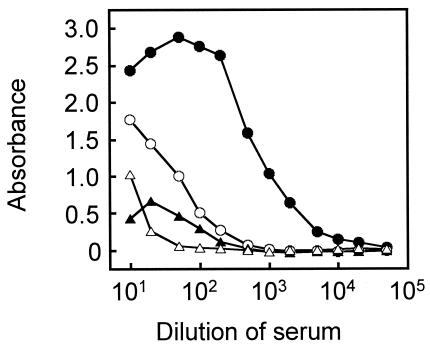

To determine the serum dilution factor best suited for a one-dilution ELISA method, dose-response absorbance curves were obtained with the four horse serum samples at dilutions from 1:10 to 1:50,000 (Fig. 3). Some sera showed prozone effects at the low dilutions of 1:10 to 1:20, whereas absorbances obtained at a 1:500 dilution or higher were too low to differentiate moderately positive and low-positive sera from the negative serum. We therefore decided to use 1:100 diluted test sera.

FIG. 3.

Dose-response absorbance curves of highly positive (solid circles), moderately positive (open circles), low-positive (solid triangles), and negative (open triangles) sera. Microplates were sensitized with a 1:10,000 dilution of rabbit anti-NS1 hyperimmune serum and 3 ng of NS1 antigen.

Determination of the cutoff value.

To determine the cutoff value between positive and negative results, 46 serum samples from yearlings born and kept in an area of northern Japan (Hokkaido) where JE is not endemic were tested by ELISA under the conditions determined above. These sera were negative for HAI antibody, and NS1 antibody titers were less than 1:80 (negative) by the immunostaining method. A positive-control serum pooled from several samples, which showed absorbances as high as the moderately positive serum used in the above experiments, was run in parallel. Absorbances obtained with yearling sera were adjusted by setting the value for the positive control to 0.5. ELISA values obtained with the yearling sera ranged from −0.064 to 0.064, with a mean of −0.009 and a standard deviation of 0.030. The confidence limit calculated from the mean and standard deviation at the probability level of 0.01% was 0.122. We tentatively decided that an ELISA value of 0.122 was the cutoff value for quantifying NS1 antibodies in horse sera.

Comparison of ELISA and immunostaining methods.

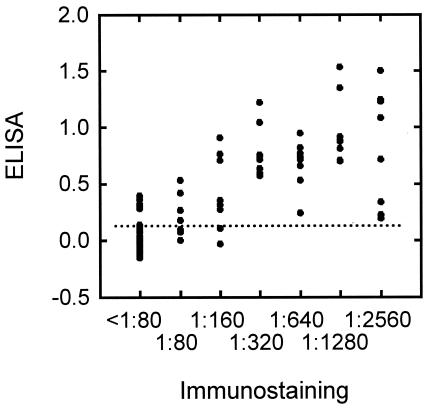

Based on the above cutoff value, the ELISA method to quantify NS1 antibodies in horse sera was evaluated by comparing the results with those obtained by the previously developed immunostaining method. For this evaluation, we used sera from horses that had resided in areas where JE was endemic (southern and central Japan) for 1 year and which were used in an earlier smaller-scale survey; their immunostaining NS1 antibody titers were already known. These samples, based on the NS1 antibody titers, consisted of 47 negative and 48 positive sera. As shown in Fig. 4, the ELISA values were significantly correlated with immunostaining NS1 antibody titers, with correlation coefficients of 0.799 for all 95 samples (P < 0.001) and 0.570 for the 48 immunostaining-positive samples (P < 0.001). A qualitative comparison (Table 1) indicated that the results obtained by ELISA were consistent with those obtained by the immunostaining method for 85.3% (81 of 95) of the samples with a sensitivity of 87.5% (42 of 48) and a specificity of 83.0% (39 of 47).

FIG. 4.

Comparison of the immunostaining and ELISA methods with horse sera positive (48 samples) or negative (47 samples) by immunostaining. The ordinate indicates ELISA values, and the abscissa indicates NS1 antibody titers obtained by the immunostaining method. A dotted line indicates the cutoff value for ELISA (0.122). NS1 antibody titers of less than 1:80 by immunostaining were regarded as negative.

TABLE 1.

Qualitative comparison between ELISA and immunostaining methods for detection of antibodies to JEV NS1, using 95 horse serum samplesa

| ELISA antibodies | No. of samples with immunostaining antibodies

|

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Positive | 42 | 8 | 50 |

| Negative | 6 | 39 | 45 |

| Total | 48 | 47 | 95 |

Collected from horses kept in areas in southern and central Japan where JEV is endemic and used in a previous study (13).

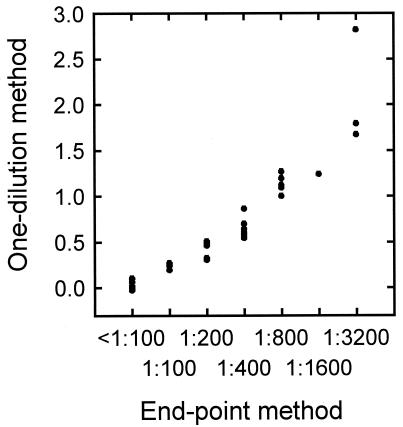

Comparison of one-dilution and endpoint methods.

To further evaluate the ELISA to quantify NS1 antibodies in horse sera, the one-dilution method was compared with the endpoint method. For the endpoint method, serial twofold dilutions of sera from 1:100 to 1:12,800 were used, and the NS1 antibody titer was expressed as the highest serum dilution giving an ELISA value of 0.122 or higher. A comparison using 30 horse serum samples (Fig. 5) indicated a significant, high correlation between the one-dilution and endpoint methods with a correlation coefficient of 0.880 (P < 0.001).

FIG. 5.

Comparison of the one-dilution method and the endpoint method in ELISA for quantifying NS1 antibodies, using 30 horse serum samples.

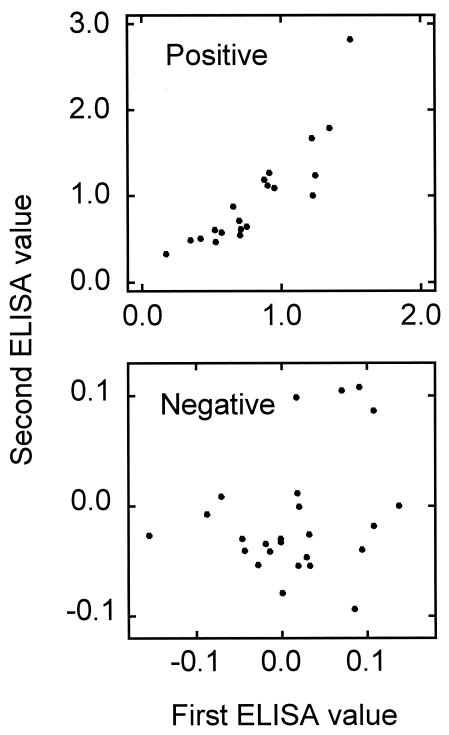

Reproducibility.

The ELISA method was examined for reproducibility, using 20 serum samples positive by both ELISA and immunostaining methods and 25 serum samples negative by both methods (Fig. 6). The ELISA values obtained in positive samples by two repeated tests were similar for most samples, with a correlation coefficient of 0.876 (P < 0.001), whereas negative sera showed a relatively large variation, with a correlation coefficient of 0.270 (P > 0.05). These results indicate that the ELISA system is reproducible and supports the cutoff value of 0.122 as appropriate for differentiating positive from negative samples and for providing consistent results.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of results obtained in duplicated ELISA tests, using 20 sera positive and 25 sera negative for NS1 antibodies.

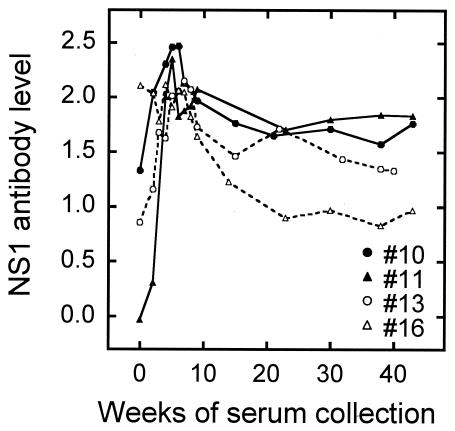

Time course of NS1 antibody level following JEV infection.

Finally, we evaluated the ELISA method by testing sera from experimentally or naturally infected horses. The period required for infected horses to seroconvert and the duration of NS1 antibodies are important factors for conducting NS1 antibody surveys. When three horses were experimentally infected with 1 × 106 to 4 × 108 PFU of JEV, ELISA values over 0.122 (positive for NS1 antibodies) were shown 13 or 23 days postinfection (Table 2). Although serum samples between 0 and 13 days postinfection were not available, the result suggests that NS1 antibodies can be used for positive identification no later than 13 days postinfection. To examine the duration, we used serum samples collected over a period of 40 or 43 weeks from four horses that had been almost simultaneously exposed to natural infection during a JE epizootic, based on the rapid rise in HAI antibody titers (Fig. 7). Since collection of sera started during the epizootic, all sera except sample number 11 were already positive for NS1 antibody at the first week of serum collection and were also positive for HAI antibody. The time courses of NS1 antibodies showed an increase in antibody level within the first 5 weeks and then a gradual decrease until the end of the observation period. The mean NS1 antibody levels at weeks 5 and 38 were 2.179 and 1.395, respectively. This indicates that, once infected, horses remain positive for NS1 antibodies for at least 40 weeks.

TABLE 2.

Increase in NS1 antibody level in experimentally infected horses

| Horse no.a | Age (yrs) | Infection dose (PFU) | NS1 antibody levelb at dayc:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −36 | −12 | 13 | 23 | |||

| 4 | 2 | 1 × 106 | — | 0.021 | — | 0.414 |

| 5 | 1 | 4 × 108 | −0.004 | — | 0.428 | — |

| 9 | 3 | 2 × 106 | — | −0.004 | — | 0.489 |

Horses were infected with the AT31 strain of JEV.

Determined by ELISA. —, samples not available.

Days relative to infection. Day −36 denotes 36 days before infection.

FIG. 7.

Time course of NS1 antibody levels in sera serially collected from four subclinically infected horses during a JE epizootic in Japan.

DISCUSSION

Nonstructural viral proteins are theoretical antigens for use in immunoassays to distinguish naturally infected from uninfected individuals in a population vaccinated with an inactivated vaccine (17). Potential use of flavivirus NS1 as a diagnostic antigen has been studied with clinical cases (7, 27). In the present study, we demonstrated that an ELISA using JEV NS1 antigen could detect subclinical infections in vaccinated horses.

Since the flavivirus protein NS1 is secreted from infected mammalian cells (18, 20), it is considered the most suitable antigen of the seven nonstructural proteins to use in an ELISA system. Furthermore, extracellular NS1 has been shown to be an effective immunogen for the induction of protective antibodies in flavivirus-infected hosts (24, 25). By a previously established immunostaining method, JEV NS1 antibodies have been detected in horses (13) and monkeys (30) following experimental infection or in humans residing in areas of Japan where JE is endemic (14). The absence of NS1 antigen in inactivated JE vaccine was confirmed by sandwich ELISA (data not shown). No significant difference was detected in ELISA values between vaccinated and unvaccinated yearlings bred in Hokkaido when the present ELISA system was used (P > 0.05; data not shown), demonstrating that NS1 antibody levels were not affected by vaccination.

The ELISA method we developed in the present study is equally as sensitive as the immunostaining method for detecting NS1 antibodies in horse sera. The quantitative and qualitative comparisons demonstrated that ELISA can be a simple alternative to the immunostaining method. However, the development of a sensitive ELISA to quantify NS1 antibodies in human sera has not been easy. Although the previously reported ELISA system for detecting NS1 antibodies in human sera (27) differentiated NS1 antibody levels in clinical cases from those from healthy vaccinated individuals in Taiwan, ELISA absorbances obtained with samples from healthy individuals were all very low; this system does not seem to detect subclinical infections among vaccinated populations. Our preliminary experiments using human sera under the same ELISA conditions established in the present study for quantifying NS1 antibodies in horse sera indicated that sera from infected patients and some individuals with subclinical infections showed higher ELISA values than sera from healthy individuals who had resided in the United States, where JEV is absent, and who had no history of yellow fever or JE vaccination. However, most of the sera positive in the immunostaining method showed low ELISA values that could not be differentiated from those obtained with the serum samples from healthy American individuals (data not shown).

Our immunostaining method uses both NS1-expressing and nonexpressing cells as antigens (14). After a standard immunostaining procedure including an avidin-biotin method, the reaction was determined to be positive when differences in stain intensity between both cell colonies were observed under a microscope. Since the stain intensity obtained with NS1-expressing cells consists of a specific reaction based on NS1 antibodies and a nonspecific reaction caused by some factors contained in test sera, the difference in stain intensity between NS1-expressing and nonexpressing cells is regarded as a specific reaction, providing a sensitive assay in which determination of the specific reaction is not hampered by nonspecific reactions. In the present ELISA, absorbances obtained from control wells without antigen were subtracted from those obtained with wells containing NS1 antigen to minimize nonspecific reactions. However, due to experimental variations (although at low levels), low levels of NS1 antibodies in human sera were not readily detected.

One explanation for the difficulty in using ELISA to detect NS1 antibodies in human sera may be the difference in the size of inoculum that corresponds to the frequency of infective mosquito bites. Horses are usually kept outside and can be exposed to a relatively large number of nocturnal vector mosquitoes, whereas the frequency of mosquito bites is thought to be much lower in humans. In previous surveys, the maximum NS1 antibody titer among naturally infected horses was extremely high (≥1:2,621,440) (13), whereas the maximum titer among patients was 1:5,120 (14). In the present study, NS1 antibody levels developed in naturally infected horses were significantly higher than those developed in horses experimentally infected with 106 to 108 PFU of JEV. On the other hand, it is also possible that the susceptibility to JEV infection or the ability to produce NS1 antibodies differs between humans and equines.

The current JEV activity in Japan provides an epidemiological model for reconsidering vaccination programs against mosquito-borne diseases. With improvements in hygiene, JEV is less frequently transmitted to humans and horses than in the past (8). Although JEV infection of swine is still reported every summer by the national JE surveillance program, except in the northern areas where JE is not endemic (28), it is thought that surveillance with a limited number of pigs kept in a restricted area far from areas where humans and horses are resident cannot always be used for estimating natural infection rates. Surveys of antibodies to JEV NS1 among humans and equines are important for protection from this vaccine-preventable disease and for studying the ecology of this mosquito-borne virus in vaccinated populations.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Japan Racing Association and by Research on Emerging and Re-Emerging Infectious Diseases, the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen, M. M., and T. Ronne. 1991. Side-effects with Japanese encephalitis vaccine. Lancet 337:1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1994. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 3.Berg, S. W., B. S. Mitchell, R. K. Hanson, R. P. Olafson, R. P. Williams, J. E. Tueller, R. J. Burton, D. M. Novak, T. F. Tsai, and F. S. Wignall. 1997. Systemic reactions in U.S. Marine Corps personnel who received Japanese encephalitis vaccine. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24:265-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke, D. S., and T. P. Monath. 2001. Flavivirus, p. 1043-1125. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields Virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 5.Halstead, S. B., and J. Jacobson. 2003. Japanese encephalitis. Adv. Virus Res. 61:103-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoshi, S., and T. Ito. 1951. Statistics of equine encephalitis in Japan. Exp. Rep. Gov. Exp. Stat. Anim. Hyg. 23:1-42. (In Japanese with English summary.) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang, J. L., J. H. Huang, R. H. Shyu, C. W. Teng, Y. L. Lin, M. D. Kuo, C. W. Yao, and M. F. Shaio. 2001. High-level expression of recombinant dengue viral NS-1 protein and its potential use as a diagnostic antigen. J. Med. Virol. 65:553-560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Igarashi, A. 1992. Japanese encephalitis: virus, infection, and control, p. 309-342. In E. Kurstak (ed.), Control of virus diseases, 2nd ed. Marcel Dekker, New York, N.Y.

- 9.Kitano, T., and A. Oya. 1996. Japanese encephalitis vaccine, p. 103-113. In Researcher's Associates National Institute of Health (ed.), Vaccine handbook. Maruzen, Tokyo, Japan.

- 10.Konishi, E. 1997. Monoclonal antibodies multireactive with parasite antigens produced by hybridomas generated from naive mice. Parasitology 115:387-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konishi, E., A. Fujii, and P. W. Mason. 2001. Generation and characterization of a mammalian cell line continuously expressing Japanese encephalitis virus subviral particles. J. Virol. 75:2204-2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konishi, E., S. Pincus, B. A. L. Fonseca, R. E. Shope, E. Paoletti, and P. W. Mason. 1991. Comparison of protective immunity elicited by recombinant vaccinia viruses that synthesize E or NS1 of Japanese encephalitis virus. Virology 185:401-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konishi, E., Shoda, M., and T. Kondo. 2004. Prevalence of antibody to Japanese encephalitis virus nonstructural 1 protein among racehorses in Japan: indication of natural infection and need for continuous vaccination. Vaccine 22:1097-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konishi, E., and T. Suzuki. 2002. Ratios of subclinical to clinical Japanese encephalitis (JE) virus infections in vaccinated populations: evaluation of an inactivated JE vaccine by comparing the ratios with those in unvaccinated populations. Vaccine 21:98-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konishi, E., and K. Uehara. 1990. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for quantifying antigens of Dermatophagoides farinae and D. pteronyssinus (Acari: Pyroglyphidae) in house dust samples. J. Med. Entomol. 27:993-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozak, M. 1986. Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell 44:283-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuno, G. 2003. Serodiagnosis of flaviviral infections and vaccinations in humans. Adv. Virus Res. 61:3-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindenbach, B. D., and C. M. Rice. 2001. Flaviviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 991-1041. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields Virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 19.Livestock Industry Bureau, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. 2003. Annual statistics of animal infectious diseases, p. 109. In Statistics on animal hygiene 2001. Association of Agriculture and Forestry Statistics, Tokyo, Japan. (In Japanese.)

- 20.Mason, P. W. 1989. Maturation of Japanese encephalitis virus glycoproteins produced by infected mammalian and mosquito cells. Virology 169:354-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McAda, P. C., P. W. Mason, C. S. Schmaljohn, J. M. Dalrymple, T. L. Mason, and M. J. Fournier. 1987. Partial nucleotide sequence of the Japanese encephalitis virus genome. Virology 158:348-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura, H. 1972. Japanese encephalitis in horses in Japan. Equine Vet. J. 4:155-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nothdurft, H. D., T. Jelinek, A. Marschang, H. Maiwald, A. Kapaun, and T. Loscher. 1996. Adverse reactions to Japanese encephalitis vaccine in travelers. J. Infect. 32:119-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlesinger, J. J., M. W. Brandriss, C. B. Cropp, and T. P. Monath. 1986. Protection against yellow fever in monkeys by immunization with yellow fever virus nonstructural protein NS1. J. Virol. 60:1153-1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlesinger, J. J., M. W. Brandriss, and E. E. Walsh. 1987. Protection of mice against dengue 2 virus encephalitis by immunization with the dengue 2 virus non-structural glycoprotein NS1. J. Gen. Virol. 68:853-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shope, R. E. 1980. Medical significance of togaviruses: an overview of diseases caused by togaviruses in man and in domestic and wild vertebrate animals, p. 47-82. In R. W. Schlesinger (ed.), The togaviruses. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 27.Shu, P. Y., L. K. Chen, S. F., Chang, Y. Y. Yueh, L. Chow, L. J. Chien, C. Chin, T. H. Lin, and J. H. Huang. 2001. Antibody to the nonstructural protein NS1 of Japanese encephalitis virus: potential application of mAb-based indirect ELISA to differentiate infection from vaccination. Vaccine 19:1753-1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takasaki, T. 2003. Japanese encephalitis, p. 75-89. In Infectious Disease Surveillance Center, National Institute of Infectious Diseases (ed.), Annual report 2001: national epidemiological surveillance of vaccine-preventable diseases. Tuberculosis and Infectious Diseases Control Division, Health Service Bureau, Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare and Infectious Disease Surveillance Center, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan. (In Japanese.)

- 29.Takehara, K., T. Mitsui, H. Nakamura, K. Fukusho, S. Kuramatsu, and J. Nakamura. 1969. Studies on Japanese encephalitis live virus vaccines. Nippon Inst. Biol. Sci. Bull. Biol. Res. 8:23-37. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanabayashi, K., R. Mukai, A. Yamada, T. Takasaki, I. Kurane, M. Yamaoka, A. Terazawa, and E. Konishi. 2003. Immunogenicity of a Japanese encephalitis DNA vaccine candidate in cynomolgus monkeys. Vaccine 21:2338-2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai, T. F., and Y. X. Yu. 1994. Japanese encephalitis vaccines, p. 671-713. In S. A. Plotkin and E. A. Mortimer, Jr. (ed.), Vaccines, 2nd ed. W. B. Saunders, Philadelphia, Pa.