Abstract

Mycobacterium brumae is a rapidly growing environmental mycobacterial species identified in 1993; so far, no infections by this organism have been reported. Here we present a catheter-related M. brumae bloodstream infection in a 54-year-old woman with breast cancer. The patient presented with high fever (39.7°C), and >1,000 colonies of M. brumae grew from a quantitative culture of blood drawn through the catheter. A paired peripheral blood culture was negative, however, suggesting circulational control of the infection. The patient was treated empirically with meropenem and vancomycin, and the fever resolved within 24 h. The catheter was removed a week later, and from the tip M. brumae was isolated a second time, suggesting catheter colonization. The organism was identified by colonial morphology, sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA gene, and biochemical tests.

CASE REPORT

A 54-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer presented to the emergency department for evaluation of a fever she had had for several hours. The patient's breast cancer had been diagnosed 6 months earlier, requiring a modified radical mastectomy and subsequent plastic surgery for a skin flap complication. The patient had also been treated with paclitaxol for the cancer, which led to a hypersensitivity skin rash that required a tapering dose of dexamethasone for 2 months. One month earlier (after completion of the steroid therapy), the patient began experiencing repeated episodes of fever, and workup failed to reveal specific etiology, although some lung atelectasis, likely related to the paclitaxol treatment, was noted on imaging studies. Eventually, the fever resolved with multiple antibiotics (various combinations of levofloxacin, cefepime, azithromycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole). The present episode of fever occurred after completion of a course of azithromycin and amoxicillin-clavulanate. Notably, during the anticancer chemotherapy the patient had not been neutropenic.

Physical examination revealed a fever of 39.7°C with otherwise normal vital signs. A right subclavian central venous catheter (CVC) was in place, with no erythema or drainage surrounding the insertion site. The mastectomy site was notable for a large, thick, and brown eschar without evidence of infection. The remainder of the examination was normal. Her laboratory data revealed mild anemia, a normal white blood cell count and differential, and normal platelet count. Paired quantitative blood cultures were drawn from the CVC line and a peripheral vein. The patient was admitted to the hospital and was empirically treated with meropenem and vancomycin.

On the second day of admission the fever resolved. Three days later, a quantitative culture of the CVC blood (9) became positive for an acid-fast bacillus (strain MDA0695) with >1,000 colonies growing on sheep blood agar from the 10 ml of blood cultured (lysis centrifugation method with an Isolator tube; Wampole Laboratories, Princeton, N.J.). The simultaneous peripheral blood culture remained negative, however. The positive culture prompted CVC removal at day 7 of hospitalization, just before discharge. This bacterium was also isolated from the removed CVC tip (625 colonies from the 5-ml sonicate solution of the tip), suggesting its colonization to the catheter without being cleared by the antibiotics. After discharge, the patient was further treated with oral azithromycin (500 mg twice a day) and gatifloxacin (400 mg daily) for 3 weeks without relapse. No episodes of fever occurred during the follow-up for 6 months.

Microbiological studies.

The growth rate of this acid-fast bacillus, strain MDA0695, suggested the likelihood of a rapidly growing mycobacterium (RGM). To identify this organism rapidly and accurately, a previously described method to analyze the sequences of the 16S rRNA gene was employed (2). Briefly, genomic DNA from culture colonies was extracted and subjected to amplification by PCR for a 1,066-bp fragment of the gene. A set of conserved bacterial primers, 5′ GCGTGCTTAACACATGCAAGTC 3′ and 5′ CGCTCGTTGCGGGACTTAACC 3′ (positions 42 to 1107 of GenBank accession no. J01859 of Escherichia coli), was used for the amplification. The amplicon was sequenced by two sets of primers using the dye terminator method in an ABI 377 sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The sequence analysis was performed through a GenBank BLAST query (GenBank; National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, Md.).

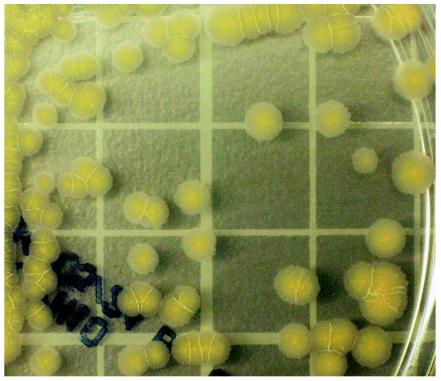

The sequencing result showed that this bacterium matched best with Mycobacterium brumae (99.6% identity, 847 of 850 base pairs) (AF480576) (4). Additionally, the organism formed flat, rough, and undulated colonies (Fig. 1), a morphological feature consistent with M. brumae (4). Thus, this identification of M. brumae was reached 4 days after isolation of the organism, or by the time of discharge of the patient. Routine biochemical tests (11), completed 28 days later, showed the organism to be scotochromagenic, positive for urease, and negative for niacin, tellurite, 68°C catalase, iron uptake, arylsulfatase, and Tween-80 hydrolysis (a nitrate reduction test was not performed). The organism grew well at 30 and 37°C incubations but not at 42°C or on MacConkey agar. The growth was retarded in the presence of 5% NaCl. Thus, most of the reactions were also compatible with M. brumae, except for chromagenicity and negative catalase and iron uptake. Overall, strain MDA0695 most likely represented a variant of M. brumae.

FIG. 1.

Colony morphology and yellow pigmentation of a 10-day culture on Middlebrook 7H10 agar of the rapidly growing Mycobacterium sp. strain MDA0695, likely a variant of M. brumae. Grid, 10 mm.

The in vitro antibiotic susceptibility of this organism was tested by using a broth dilution method and was interpreted according to guidelines of the National Committee on Clinical Laboratory Standards (6). The strain was found to be susceptible to amikacin (MIC, ≤0.5 μg/ml), tobromycin (MIC, ≤2 μg/ml), ciprofloxacin (MIC, 0.12 μg/ml), clarithromycin (MIC, ≤0.25 μg/ml), minocycline (MIC, ≤0.25 μg/ml), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (MIC of trimethoprim, 2 μg/ml; MIC of sulfamethoxazole, 38 μg/ml), but it was resistant to cefoxitin (MIC, >64 μg/ml) and imipenem (MIC, >32 μg/ml).

Analysis.

It has been realized in recent years that sequencing analysis of the 16S rRNA gene offers rapid and accurate identification of various bacteria, particularly mycobacteria that are fastidious (2, 10). Our laboratory routinely uses sequencing analysis of a portion of the 16S rRNA gene to provide quick and timely identification of all mycobacterial isolates (2). The sequencing method has also been used to identify rare bacterial species and establish new species (3).

The number of RGM has expanded significantly over the past decade or so, owing to better recognition and identification of these organisms. M. brumae is a nonchromogenic RGM species established in 1993 by Luquin et al. (4). The organism is rod shaped, gram positive, and acid-alcohol fast, and it is able to form clumps and cords. It grows within 4 to 5 days. Of the initial 11 strains studied, 8 were isolated from water samples from a river in Spain, 2 were from soil, and 1 was from human sputum of an asymptomatic individual. To our knowledge, no infections by this organism have been reported previously. It is likely that, in view of the limited experience with this organism, traditional biochemical tests may be unable to provide definitive identification of this organism. In our case, had the sequencing method not been used, the organism would have been misidentified.

RGM are being recognized as causing catheter-related infections, with an estimated incidence of 1% (1, 8). M. fortuitum, M. chelonae, and M. mucogenicum are the most frequent culprits in our experience (2, 7). Rare mycobacteria, such as the present case and others (14), have also been recognized in recent years. Like other CVC-related infections, the likely involvement of mycobacteria is probably related to the duration of catheter placement, the location of the site of insertion, and the type of catheters (5). The incidence also varies with geographic location: the southern coastal states, especially Texas and Florida, are areas where RGM infections are endemic (13). It is presently uncertain whether a specific underlying disease per se, such as breast cancer in our patient, may be an independent predisposing factor. A previous study (7) showed that 4 of 15 patients with catheter-related RGM bacteremias had breast cancer as the primary disease.

Our M. brumae strain was resistant to imipenem and cefoxitin but was susceptible to several other antibiotics. While there is no other data on M. brumae for comparison, this drug resistance pattern resembles those of M. chelonae and M. abscessus more than that of M. fortuitum. In a recent study of 75 strains of M. chelonae and M. abscessus (15), 40% were resistant to imipenem and 47% were resistant to cefoxitin. In contrast, M. fortuitum strains are rarely resistant to these two antibiotics (12). In our patient, despite the imipenem resistance the initial combination of antibiotics appeared effective in clearing the infection, because she defervesced rapidly. However, the antibiotics did not clear the catheter colonization by the organism. Therefore, catheter removal was the ultimate step to prevent potential relapse in this patient. This point has been realized earlier in catheter-related RGM infections (7).

Acknowledgments

We thank Mohammad Ali-Golshan for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by a University Cancer Foundation grant (to X.Y.H.) from The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center and by an institutional core research grant (CA16672) from the National Institutes of Health for the Sequencing Core Facility.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gaviria, J. M., P. J. Garcia, S. M. Garrido, L. Corey, and M. Boeckh. 2000. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: characteristics of respiratory and catheter-related infections. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 6:361-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han, X. Y., A. S. Pham, J. J. Tarrand, P. K. Sood, and R. Luthra. 2002. Rapid and accurate identification of mycobacteria by sequencing hypervariable regions of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 118:796-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han, X. Y., A. S. Pham, J. J. Tarrand, K. V. Rolston, L. O. Helsel, and P. N. Levett. 2002. Bacteriologic characterization of 36 strains of Roseomonas species and proposal of Roseomonas mucosa sp. nov. and Roseomonas gilardii subsp. rosea subsp. nov. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 120:256-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luquin, M., V. Ausina, V. Vincent-Levey-Frebault, M. A. Laneelle, F. Belda, M. Garcia-Barcelo, G. Prats, and M. Daffe. 1993. Mycobacterium brumae sp. nov., a rapidly growing, nonphotochromogenic mycobacterium. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 43:405-413. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mermel, L. A., B. M. Farr, R. J. Sherertz, I. I. Raad, N. O'Grady, J. S. Harris, and D. E. Craven. 2001. Guidelines for the management of intravascular catheter related infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:1249-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other aerobic actinomycetes. Approved standard M24-A. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa. [PubMed]

- 7.Raad, I. I., S. Vartivarian, A. Khan, and G. P. Bodey. 1991. Catheter-related infections caused by the Mycobacterium fortuitum complex: 15 cases and review. Rev. Infect. Dis. 13:1120-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roy, V., and D. Weisdorf. 1997. Mycobacterial infections following bone marrow transplantation: a 20-year retrospective review. Bone Marrow Transplant. 19:467-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tarrand, J. J., C. Guillot, M. Wenglar, J. Jackson, J. D. Lajeunesse, and K. V. Rolston. 1991. Clinical comparison of the resin-containing Bactec 26 plus and the Isolator 10 blood culturing systems. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:2245-2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turenne, C. Y., L. Tschetter, J. Wolfe, and A. Kabani. 2001. Necessity of quality-controlled 16S rRNA gene sequence databases: identifying nontuberculous Mycobacterium species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3637-3648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vincent, V., B. A. Brown-Elliott, K. C. Jost, and R. J. Wallace. 2003. Mycobacterium: phenotypic and genotypic identification, p. 560-584. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, J. H. Jorgensen, M. A. Pfaller, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 8th ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 12.Wallace, R. J., B. A. Brown, and G. O. Onyi. 1991. Susceptibility of Mycobacterium fortuitum biovar fortuitum and the two subgroups of Mycobacterium chelonae to imipenem, cefmetazole, cefoxitin, and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:773-775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallace, R. J., L. C. Steele, A. Labidi, and V. A. Silcox. 1989. Heterogeneity among isolates of rapidly growing mycobacteria responsible for infections following augmentation mammaplasty despite case clustering in Texas and other southern coastal states. J. Infect. Dis. 160:281-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woo, P. C. Y., H. W. Tsoi, K. W. Leung, P. N. L. Lum, A. S. P. Leung, C. H. Ma, K. M. Kam, and K. Y. Yeun. 2000. Identification of Mycobacterium neoaurum isolated from a neutropenic patient with catheter-related bacteremia by 16S rRNA sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3515-3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yakrus, M. A., S. M. Hernandez, M. M. Floyd, D. Sikes, W. R. Butler, and B. Metchock. 2001. Comparison of methods for identification of Mycobacterium abscessus and M. chelonae isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4103-4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]