Abstract

A total of 19,753 strains of gram-negative rods collected during two 6-month periods (October 2000 to March 2001 and November 2001 to April 2002) from 13 clinical laboratories in the Kinki region of Japan were investigated for the production of metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs). MBLs were detected in 96 (0.5%) of the 19,753 isolates by the broth microdilution method, the 2-mercaptopropionic acid inhibition test, and PCR and DNA sequencing analyses. MBL-positive isolates were detected in 9 of 13 laboratories, with the rate of detection ranging between 0 and 2.6% for each laboratory. Forty-four of 1,429 (3.1%) Serratia marcescens, 22 of 6,198 (0.4%) Pseudomonas aeruginosa, 21 of 1,108 (1.9%) Acinetobacter spp., 4 of 544 (0.7%) Citrobacter freundii, 3 of 127 (2.4%) Providencia rettgeri, 1 of 434 (0.2%) Morganella morganii, and 1 of 1,483 (0.1%) Enterobacter cloacae isolates were positive for MBLs. Of these 96 MBL-positive strains, 87 (90.6%), 7 (7.3%), and 2 (2.1%) isolates carried the genes for IMP-1-group MBLs, IMP-2-group MBLs, and VIM-2-group MBLs, respectively. The class 1 integrase gene, intI1, was detected in all MBL-positive strains, and the aac (6′)-Ib gene was detected in 37 (38.5%) isolates. Strains with identical PCR fingerprint profiles in a random amplified polymorphic DNA pattern analysis were isolated successively from five separate hospitals, suggesting the nosocomial spread of the organism in each hospital. In conclusion, many species of MBL-positive gram-negative rods are distributed widely in different hospitals in the Kinki region of Japan. The present findings should be considered during the development of policies and strategies to prevent the emergence and further spread of MBL-producing bacteria.

Metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) are enzymes belonging to Ambler's class B that can hydrolyze a wide variety of β-lactams, including penicillins, cephems, and carbapenems (14, 30, 42). The acquisition by gram-negative rods of MBLs, which are often encoded by mobile genetic elements such as cassettes inserted into integrons, confers a multidrug resistance profile against many clinically important β-lactams as well as other antimicrobial agents (1). This fact raises a significant problem with respect to antimicrobial chemotherapy (38). Plasmid-mediated MBLs are categorized into three major molecular types: they are IMP-type, VIM-type, and SPM-type enzymes (14, 21, 30, 32, 39, 42). Among them, IMP-1-type MBLs have been identified in various gram-negative bacilli belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae and in several non-glucose-fermenters, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp. (13, 18, 19, 20, 36-38, 43). Furthermore, in Japan, several variants of the IMP-1 type, including IMP-3 from Shigella flexneri (15), IMP-6 from Serratia marcescens (47), IMP-10 from P. aeruginosa and Alcaligenes xylosoxidans (16), and IMP-11 (EMBL/GenBank accession no. AB074437) from P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii, have been characterized recently. VIM-type MBLs, including VIM-1 and VIM-2 from P. aeruginosa isolates in Italy and France, respectively (21, 32), were first described in 1999. Outbreaks of VIM-type MBL-positive strains have also been reported in Italy and Greece (8, 40). SPM-1, a member of the third group of plasmid-mediated MBLs, was recently detected in P. aeruginosa isolates in Brazil, and SPM-1 producers appear to be widely disseminated in Brazil (11).

Previously reported survey data from the Kinki region of Japan revealed that 0.7% of isolates produced IMP-1-group MBLs (44). The prevalence of IMP-1-group MBLs among gram-negative rods has also been investigated (19, 36); however, the prevalence of the new plasmid-mediated MBLs, such as the IMP-2 group (33) and the VIM-2 type (32), in Japan remains unclear.

For the present study, to assess the prevalence and types of MBL-positive bacteria in the Kinki region of Japan, we investigated almost 20,000 isolates collected from 12 general hospitals and one commercial laboratory.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

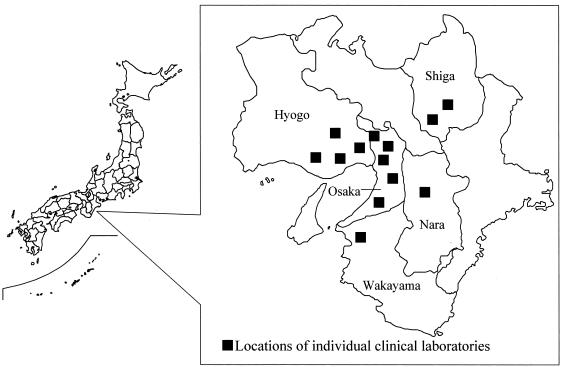

This laboratory-based surveillance study was conducted with the cooperation of 13 institutions (12 hospital clinical laboratories and one commercial laboratory) in the Kinki region, which is located in western Japan (Fig. 1), with the assistance of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases of Japan. Between October 2000 and March 2001 (first study period) and November 2001 and April 2002 (second study period), a total of 19,753 isolates of gram-negative bacilli, including P. aeruginosa (6,198 isolates), Acinetobacter spp. (1,108 isolates), Escherichia coli (4,347 isolates), Klebsiella pneumoniae (2,354 isolates), S. marcescens (1,429 isolates), Enterobacter cloacae (1,483 isolates), Citrobacter freundii (544 isolates), Klebsiella oxytoca (627 isolates), Enterobacter aerogenes (454 isolates), Proteus mirabilis (470 isolates), Morganella morganii (434 isolates), Proteus vulgaris (178 isolates), and Providencia rettgeri (127 isolates), were isolated from various clinical specimens and then tested. A single isolate was selected from each patient and identified by use of a MicroScan Neg Combo 5J panel (Dade Behring, Tokyo, Japan). Moreover, Acinetobacter isolates were identified by use of an ID TEST NF-18 panel (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). For Acinetobacter spp. other than A. baumannii, PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene was performed, with genomic DNA as the template, according to a previously published protocol (34), and the amplicons were sequenced. The sequence data were submitted to the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) database to check the identity or similarity of each sequence against the database by use of the FASTA program (http://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/search/Welcome-e.html).

FIG. 1.

Locations of the 13 institutions involved in this study of the Kinki region of Japan.

First screening for MBL production.

MIC criteria for the first screening of MBL producers were >16 μg of ceftazidime/ml for Acinetobacter spp. and >16 μg of both ceftazidime and cefoperazone-sulbactam/ml for gram-negative organisms other than Acinetobacter spp. The production of MBLs was assessed with a 2-mercaptopropionic acid inhibition (2-MPA) test as described previously (2, 37). Test strains were cultured, adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard, diluted with 0.85% saline, and inoculated onto Mueller-Hinton agar plates according to the protocol recommended by the NCCLS (27). Two Senci-Disks (Becton Dickinson Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) containing 30 μg of ceftazidime, 10 μg of imipenem, and 30 μg of cefepime were placed at a distance of 50 mm from each other on the plate, and one blank disk was placed near one of the Senci-Disks at a distance of 20 mm. Two to 3 μl of 2-MPA was added to the blank disk. After an overnight incubation at 35°C, if an expansion of the growth inhibition zone around either the ceftazidime, imipenem, or cefepime disk was observed, the strain was interpreted as being positive for MBL.

Susceptibility testing for antimicrobial agents.

The MICs of antimicrobial agents for isolates that tested positive in the 2-MPA test were subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing by the broth microdilution method with dry plates (Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), which conformed to NCCLS guidelines (26, 28). The following antimicrobial agents and concentrations were used: piperacillin (2 to 128 μg/ml), piperacillin-tazobactam (1-4 to 128-4 μg/ml), ceftazidime (1 to 128 μg/ml), cefepime (1 to 128 μg/ml), cefoperazone-sulbactam (1-0.5 to 128-64 μg/ml), aztreonam (1 to 128 μg/ml), cefmetazole (1 to 128 μg/ml), moxalactam (1 to 128 μg/ml), meropenem (0.25 to 32 μg/ml), imipenem (0.25 to 32 μg/ml), gentamicin (1 to 8 μg/ml), amikacin (4 to 32 μg/ml), minocycline (4 to 8 μg/ml), levofloxacin (2 to 4 μg/ml), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (9.5-0.5 to 38-2 μg/ml), and chloramphenicol (8 to 16 μg/ml). E. coli ATCC 25922 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were used as reference strains for quality control of the tests (26).

PCR amplification and DNA sequencing.

Isolates that tested positive in the 2-MPA test were then assessed for their MBL type by PCR and DNA sequencing. PCRs were performed as described previously (35). PCR primers for the amplification of each MBL gene were constructed as described in previous reports for blaIMP-1 (35), blaIMP-2 (33), and blaVIM-2 (32). Primers for the amplification of integrase genes (intI1, intI2, and intI3) (31, 37) and the aminoglycoside resistance gene [aac (6′)-Ib] (35) were described previously. The PCR and DNA sequencing primers used are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primers for PCR and sequencing of MBL genes

| Target | Use | Primer name | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) | Positiona | Product length (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMP-1 | Amplification | IMP1L | CTACCGCAGCAGAGTCTTTG | 47-66 | 587 | 35 |

| IMP2R | AACCAGTTTTGCCTTACCAT | 633-614 | ||||

| Sequencing | IMP1-SQ-F | ACCGCAGCAGAGTCTTTGCC | 49-68 | 587 | 37 | |

| IMP1-SQ-R | ACAACCAGTTTTGCCTTACC | 635-616 | ||||

| IMP-2 | Amplification | IMP2L | GTGTATGCTTCCTTTGTAGC | 23-42 | 174 | 33 |

| IMP2R | CAATCAGATAGGCGTCAGTGT | 196-176 | ||||

| Sequencing | IMP2-SQ-F | GTTTTATGTGTATGCTTCC | 16-34 | 678 | 37 | |

| IMP2-SQ-R | AGCCTGTTCCCATGTAC | 693-677 | ||||

| VIM | Amplification | VIMB | ATGGTGTTTGGTCGCATATC | 152-171 | 510 | 32 |

| VIMF | TGGGCCATTCAGCCAGATC | 661-643 | ||||

| Sequencing | VIM2-SQ-F | ATGTTCAAACTTTTGAGTAAG | 1-21 | 801 | 37 | |

| VIM2-SQ-R | CTACTCAACGACTGAGCG | 801-784 |

Position number 1 for every MBL gene corresponds to the first base of the start codon.

PCR products were sequenced by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method (45) in an automated DNA sequencer (ABI 3100; Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Similarity searches against sequence databases were performed with an updated version of the FASTA program available from the Center for Information Biology and DNA Data of Japan for Biotechnology Information server of the National Institute of Genetics of Japan (http://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/).

RAPD pattern analysis.

The isolates that were confirmed to be positive for the MBL gene by PCR and chromosomal DNA typing were analyzed by random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis to generate a DNA fingerprint (29). The RAPD primers were ERIC2 (5′-AAGTAAGTGACTGGGGTGAGCG-3′) for Enterobacteriaceae other than S. marcescens (41), HLWL-74 (5′-CGTCTATGCA-3′) and 1254 (5′-AACCCACGCC-3′) for S. marcescens (12), 272 (5′-AGCGGGCCAA-3′) for P. aeruginosa (6), and A5 (5′-GCCGGGGCCT-3′) for Acinetobacter spp. (31).

RESULTS

Prevalence of MBL-positive isolates.

The prevalence of isolates that produced MBLs is shown in Table 2. Seven hundred fifty-seven isolates (3.8%) fulfilled the MIC criteria for the production of MBLs. Of these 757 isolates, 96 (12.7%) were positive in the 2-MPA test. Of these 96 positive isolates, only 1 E. cloacae isolate appeared to have a weak and ambiguous growth inhibition zone (data not shown) in the 2-MPA test. All 96 isolates that tested positive in the 2-MPA test were positive for at least one MBL gene by PCR and DNA sequencing. The numbers of MBL-positive isolates with an MBL gene were 44 (3.1%) for S. marcescens, 22 (0.4%) for P. aeruginosa, 21 (1.9%) for Acinetobacter spp., 4 (0.7%) for C. freundii, 3 (2.4%) for Providencia rettgeri, 1 (0.2%) for M. morganii, and 1 (0.1%) for E. cloacae. Of 21 isolates of Acinetobacter spp., 18 were identified as A. baumannii, and the remaining three strains were A. johnsonii, A. junii, and A. calcoaceticus according to 16S rRNA sequencing analysis and their biochemical properties.

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of metallo-β-lactamase-producing isolates

| Organism | No. of isolates collected

|

No. of isolates fulfilling MIC criteria

|

No. (%) of MBL-producing isolatesc

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000a | 2001b | Total | 2000a | 2001b | Total | 2000a | 2001b | Total | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 2,645 | 3,553 | 6,198 | 141 | 141 | 282 | 8 (0.3) | 14 (0.4) | 22 (0.4) |

| Escherichia coli | 1,334 | 3,013 | 4,347 | 3 | 8 | 11 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 867 | 1,487 | 2,354 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Serratia marcescens | 615 | 814 | 1,429 | 101 | 55 | 156 | 26 (4.2) | 18 (2.2) | 44 (3.1) |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 565 | 918 | 1,483 | 81 | 90 | 171 | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 388 | 720 | 1,108 | 20 | 14 | 34 | 13 (3.4) | 8 (1.1) | 21 (1.9) |

| Citrobacter freundii | 234 | 310 | 544 | 23 | 37 | 60 | 0 (0) | 4 (1.3) | 4 (0.7) |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 227 | 400 | 627 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 194 | 260 | 454 | 11 | 12 | 23 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Proteus mirabilis | 176 | 294 | 470 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Morganella morganii | 166 | 268 | 434 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Proteus vulgaris | 97 | 81 | 178 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Providencia rettgeri | 45 | 82 | 127 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 3 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.4) |

| Total | 7,553 | 12,200 | 19,753 | 391 | 366 | 757 | 51 (0.7) | 45 (0.4) | 96 (0.5) |

First study period, October 2000 to March 2001.

Second study period, November 2001 to April 2002.

Percentages were calculated as follows: no. of MBL-producing isolates/no. of isolates collected × 100%.

The results of the MBL assessments in each laboratory are shown in Table 3. These 13 laboratories included 5 laboratories in university hospitals, 7 laboratories in general hospitals, and 1 commercial laboratory. MBL-positive isolates were detected in 9 of 13 laboratories; the overall rate of detection was 0.5% and ranged from 0 to 2.6% in each laboratory.

TABLE 3.

Isolation frequencies of metallo-β-lactamase-producing isolates in 13 laboratories

| Laboratory code (type) | No. of isolates collected

|

No. (%) of MBL-producing isolatesc

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000a | 2001b | Total | 2000a | 2001b | Total | |

| A (university hospital) | 1,293 | 1,571 | 2,864 | 7 (0.5) | 3 (0.2) | 10 (0.4) |

| B (university hospital) | 951 | 1,281 | 2,232 | 5 (0.5) | 11 (0.9) | 16 (0.7) |

| C (university hospital) | 1,139 | 1,003 | 2,142 | 31 (2.7) | 24 (2.4) | 55 (2.6) |

| D (university hospital) | 965 | 873 | 1,838 | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| E (university hospital) | 883 | 728 | 1,611 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| F (general hospital) | 482 | 627 | 1,109 | 0 (0) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) |

| G (general hospital) | 463 | 453 | 916 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| H (general hospital) | 347 | 421 | 768 | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) |

| I (general hospital) | 304 | 280 | 584 | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) |

| J (general hospital) | 255 | 251 | 506 | 4 (1.5) | 2 (0.8) | 6 (1.2) |

| K (general hospital) | 212 | 293 | 505 | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.4) |

| L (general hospital) | 259 | 152 | 411 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| M (commercial laboratory) | NDd | 4267 | 4267 | NDd | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

First study period, October 2000 to March 2001.

Second study period, November 2001 to April 2002.

Percentages are no. of MBL-producing isolates/no. of isolates collected × 100.

ND, not determined.

Genetic characterization of MBL-producing isolates.

Some characteristics and selected clinical associations of MBL-producing isolates are shown in Table 4. All MBL-producing isolates were isolated from inpatients with bacterial infections. With respect to the MBL genotypes, 87 (90.6%) isolates carried genes encoding IMP-1-group MBLs, including IMP-1, IMP-3, IMP-6, and IMP-10. Similarly, seven (7.3%) isolates carried genes for IMP-2-group MBLs, such as IMP-2, IMP-8, and IMP-11. Genes encoding VIM-2-group MBLs, such as VIM-2, VIM-3, and VIM-6, were carried by two (2.1%) isolates. Genes for IMP-1-group MBLs were detected in 21 isolates of P. aeruginosa at hospitals B, C, and H; 14 isolates of Acinetobacter spp. at hospitals A, C, F, H, and J; 44 isolates of S. marcescens at hospitals A and C; 4 isolates of C. freundii at hospital C; 3 isolates of Providencia rettgeri at hospital C; and 1 isolate of M. morganii at hospital C. Genes for IMP-2-group MBLs were detected in seven isolates of Acinetobacter spp. at hospitals J and K. Genes for VIM-2-group MBLs were detected in one isolate of P. aeruginosa at hospital I and one isolate of E. cloacae at hospital D. The integrase gene (identified as intI1) was detected in all 96 MBL-producing isolates. The aac (6′)-Ib gene was detected in 37 (38.5%) MBL-positive isolates.

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of MBL-producing strains and selected clinical data

| Species (no. of strains) | RAPD type | MBL typea (No. of strains) | No. of aac(6′)-Ib-a positive strains | Hospital | Wardb (no. of strains) | Antibiogramc (no. of strains) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa (22) | a | IMP-1 (5) | 4 | B | ICU (1), NICU (1), pediatrics 7E (3) | GM, MINO, ST, CP (4), GM, ST, CP (1) |

| b | IMP-1 (6) | 6 | B | Internal medicine 11E (2), internal medicine 13E (1), internal medicine 8E (1), pediatrics 7E (2) | GM, MINO, ST, CP (6) | |

| c | IMP-1 (1) | 0 | B | Internal medicine 11E (1) | GM, MINO, LVFX, ST, CP (1) | |

| d | IMP-1 (1) | 1 | B | Urology 8W (1) | GM, MINO, ST, CP (1) | |

| e | IMP-1 (1) | 0 | B | Urology 8W (1) | MINO, ST, CP (1) | |

| f | IMP-1 (2) | 2 | B | Urology 8W (2) | GM, AMK, MINO, LVFX, ST, CP (1), GM, MINO, LVFX, ST, CP (1) | |

| g | IMP-1 (1) | 0 | C | Emergency 1S (1) | GM, MINO, LVFX, ST, CP (1) | |

| h | IMP-1 (1) | 0 | C | Emergency 1S (1) | GM, AMK, MINO, LVFX, ST, CP (1) | |

| i | IMP-1 (1) | 0 | C | Plastic surgery 4C (1) | GM, MINO, LVFX, ST, CP (1) | |

| j | IMP-1 (2) | 2 | H | Urology 5W (1), internal medicine MICU (1) | GM, MINO, LVFX, ST, CP (2) | |

| k | VIM-2 (1) | 1 | I | Internal medicine 6E (1) | GM, MINO, LVFX, ST, CP (1) | |

| A. baumannii (18) | A | IMP-1 (8) | 8 | A | Internal medicine 115NS (8) | GM, ST, CP (8) |

| B | IMP-1 (1) | 1 | C | Otolaryngology 7E (1) | GM, CP (1) | |

| C | IMP-1 (1) | 1 | F | Cardiac surgery ICU (1) | ST, CP (1) | |

| D | IMP-1 (1) | 1 | F | Brain surgery SCU (1) | ST, CP (1) | |

| E | IMP-1 (1) | 1 | H | Internal medicine 7E (1) | CP (1) | |

| F1 | IMP-2 (5) | 0 | J | Surgery W6 (3), brain surgery W7 (2) | ST, CP (5) | |

| F2 | IMP-2 (1) | 0 | K | Internal medicine 5A (1) | GM, ST, CP (1) | |

| A. junii (1) | IMP-1 (1) | 1 | C | Otolaryngology 7E (1) | GM, ST (1) | |

| A. calcoaceticus (1) | IMP-1 (1) | 0 | J | Internal medicine ICU (1) | AMK, ST (1) | |

| A. johnsonii (1) | IMP-2 (1) | 0 | K | Internal medicine 5A (1) | ST (1) | |

| S. marcescens (44) | 1 | IMP-1 (2) | 0 | A | Neurology 75NS (1), urology 65NS (1) | MINO, LVFX, ST, CP (1) MINO, LVFX, CP (1) |

| 2 | IMP-1 (1) | 0 | C | Urology 7F (1) | MINO, ST, CP (1) | |

| 3 | IMP-1 (41) | 0 | C | Emergency 1S (14), internal medicine CCU (13), urology 7F (5), brain surgery 6F (2), cardiac surgery 4S (2), internal medicine 3S (2), plastic surgery 5C (2), surgery 4F (1) | CP (7), AMK (1), MINO (1), MINO, CP (1) | |

| Providencia rettgeri (3) | 1 | IMP-1 (2) | 2 | C | Urology 7F (2) | ST, CP (2) |

| 2 | IMP-1 (1) | 1 | C | Internal medicine 83 (1) | MINO, LVFX, ST (1) | |

| Citrobacter freundii (4) | 1 | IMP-1 (4) | 4 | C | Internal medicine CCU (3), internal medicine 3S (1) | CP (1) |

| Morganella morganii (1) | IMP-1 (1) | 1 | C | Urology 7F (1) | MINO, LVFX, ST (1) | |

| Enterobacter cloacae (1) | VIM-2 (1) | 0 | D | Pediatrics E6 (1) | MINO, ST, CP (1) |

MBL types: IMP-1, IMP-1-group MBLs, including IMP-1, IMP-3, IMP-6, and IMP-10; IMP-2, IMP-2-group MBLs, including IMP-2, IMP-8, and IMP-11; VIM-2, VIM-2 MBLs.

ICU, intensive care unit; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; MICU, medical intensive care unit; SCU, surgical care unit; CCU, coronary care unit.

Antibiogram: AMK, amikacin (64 μg/ml); GM, gentamicin (16 μg/ml); MINO, minocycline (16 μg/ml); LVFX, levofloxacin (8 μg/ml); ST, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (4 μg/ml); CP, chloramphenicol (32 μg/ml).

Of 96 MBL-positive isolates, 68 (70.8%), 8 (8.3%), 7 (7.3%), 4 (4.1%), 3 (3.1%), 2 (2.1%), 2 (2.1%), and 2 (2.1%) were recovered from urine, sputum, throats, pus, drains, blood, tracheal tubes, and other samples, respectively. The majority of A. baumannii isolates were recovered from respiratory tract specimens, and bacterial species belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae and P. aeruginosa were recovered from urine.

RAPD typing with the 272 primer of 22 P. aeruginosa isolates from four hospitals identified 11 distinct types. Two or more isolates with the same banding patterns were observed for two of the four hospitals. Of 21 A. baumannii isolates from six hospitals, 8 isolates (same ward) from hospital A were found to belong to the same clonal lineage, and 5 isolates (two wards) from hospital J belonged to another clonal lineage. Of 44 S. marcescens isolates from hospitals A and C, 2 isolates from hospital A had the same pattern, and two distinct patterns were observed for 42 isolates recovered from hospital C. Forty-one of the isolates from hospital C shared the same pattern, and they had been isolated from eight different wards. At hospital C, the two isolates of Providencia rettgeri had the same pattern, and four isolates of C. freundii also shared the same pattern. Genetically related isolates, such as those of P. aeruginosa in hospital B, A. baumannii in hospitals A and J, and S. marcescens, Providencia rettgeri, and C. freundii in hospital C, were isolated from the same ward, suggesting a nosocomial spread of these organisms.

Susceptibility of MBL-producing isolates.

The results of susceptibility tests are shown in Table 5. The susceptibilities of the 96 MBL-positive isolates to several antimicrobial agents varied. For the MBL-producing bacterial species belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae, P. aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter spp., the MICs at which 50% of the isolates were inhibited (MIC50s) of imipenem were 32, 16, and 16, respectively, and the MIC90s of the same agent were >32, 32, and 32 μg/ml, respectively. For species belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae, piperacillin-tazobactam, aztreonam, gentamicin, amikacin, and levofloxacin had relatively high activities. P. aeruginosa isolates had similar or lower susceptibilities to non-β-lactam agents than bacterial species belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae or Acinetobacter spp. Piperacillin-tazobactam and cefoperazone-sulbactam appeared to have the most potent activities against MBL-producing Acinetobacter spp. The MICs for E. coli ATCC 25922 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were within the NCCLS control ranges.

TABLE 5.

Susceptibility of MBL-producing isolates to various antimicrobial agents

| Antimicrobial agenta | MIC (μg/ml) for organism

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Enterobacteriaceae (n = 53)

|

P. aeruginosa (n = 22)

|

Acinetobacter spp. (n = 21)

|

|||||||

| Range | MIC50 | MIC90 | Range | MIC50 | MIC90 | Range | MIC50 | MIC90 | |

| Ceftazidime | 16->128 | >128 | >128 | 64->128 | 128 | >128 | 128->128 | >128 | >128 |

| Piperacillin | 8->128 | 16 | >128 | 4->128 | 16 | >128 | 8->128 | 32 | 128 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactama | ≤1->128 | 8 | 16 | 2->128 | 8 | >128 | ≤1-32 | ≤1 | 4 |

| Cefepime | 2->128 | 64 | 128 | 32->128 | 64 | >128 | 64->128 | 128 | 128 |

| Cefoperazone-sulbactam | 32->128 | >128 | >128 | 64->128 | 64 | >128 | ≤1-16 | 2 | 4 |

| Aztreonam | ≤1-64 | 16 | 32 | 2->128 | 8 | 32 | 4-32 | 16 | 32 |

| Cefmetazole | >128->128 | >128 | >128 | >128->128 | >128 | >128 | 64->128 | >128 | >128 |

| Latamoxef | 64->128 | >128 | >128 | >128->128 | >128 | >128 | >128->128 | >128 | >128 |

| Meropenem | 1->32 | >32 | >32 | 16->32 | 32 | >32 | 8->32 | 32 | >32 |

| Imipenem | 1->32 | 32 | >32 | 1->32 | 16 | 32 | 8->32 | 16 | 32 |

| Gentamicin | ≤1-4 | ≤1 | 2 | 2->8 | >8 | >8 | ≤1->8 | 8 | >8 |

| Amikacin | ≤4->32 | 16 | 32 | ≤4->32 | 16 | 32 | ≤4->32 | 8 | 16 |

| Minocycline | ≤4->8 | ≤4 | >4 | >8->8 | >8 | >8 | ≤4-≤4 | ≤4 | ≤4 |

| Levofloxacin | ≤2->4 | ≤2 | 4 | ≤2->4 | 4 | >4 | ≤2-4 | ≤2 | ≤2 |

| Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim | ≤0.5->2 | ≤0.5 | >2 | >2->2 | >2 | >2 | ≤0.5->2 | >2 | >2 |

| Chloramphenicol | ≤8->16 | 16 | >16 | >16->16 | >16 | >16 | ≤8->16 | >16 | >16 |

Tazobactam was tested at a fixed concentration of 4 μg/ml.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the distribution and prevalence of MBL-producing gram-negative rods with the cooperation of 12 clinical laboratories at large-scale general hospitals and one commercial clinical laboratory in the Kinki region of Japan. Such isolates were identified at a rate of 0.5%. In a previous laboratory-based surveillance conducted in 1998 and 2000, MBL-producing isolates were found only in specimens collected by a commercial laboratory (44). However, MBL producers were isolated from 9 of 13 laboratories in the present multi-institutional surveillance study, and the prevalence of MBL-positive isolates ranged from 0 to 2.6%, suggesting that there is a continuous proliferation of MBL producers in Japan. The majority of MBL producers detected in the present study were S. marcescens, P. aeruginosa, or Acinetobacter spp., which was similar to the results of previous studies (33, 37). Moreover, in the present study, several strains of Providencia rettgeri and M. morganii that produce MBLs were found, suggesting that plasmid-mediated horizontal transfer of the MBL genes is so far likely to occur continuously among gram-negative bacilli, as reported previously (14, 35). This finding gives us an alert on the further dissemination of MBL genes among various gram-negative bacilli. In the present study, the predominant type of MBL in Japan was found to be the IMP-1 group, but MBLs belonging to the IMP-2 group and the VIM-2 group were also detected. MBL genes encoding blaIMP-2 and blaVIM-2 have been reported in Italy (21, 33), France (32), Korea (22), Taiwan (45, 46), Portugal (7), and Greece (25). Recently, a genetic classification of the MBLs detected in Japan was reported (37), but the frequency of isolation of MBL producers from clinical specimens was not described. The present study provides the first reported data on the prevalence of bacteria carrying the genes for MBLs, including IMP-1, IMP-2, and VIM-2 MBLs, in the western portion of Japan.

A total of 96 MBL-positive isolates were typed by RAPD analysis to determine the stabilities of the strain genotypes. The RAPD typing results are summarized in Table 4. The 16 isolates of P. aeruginosa from hospital B yielded seven different RAPD patterns and originated from six different wards. Eight A. baumannii isolates from hospital A had the same RAPD pattern and were from the same ward. The five A. baumannii isolates carrying the genes for IMP-2-group MBLs, isolated from two wards of hospital J, appeared to be of the same clonal lineage. This is the first report of nosocomial spread of A. baumannii isolates carrying genes for IMP-2-group MBLs in Japan. Of the 41 S. marcescens isolates from hospital C, 13 isolates from the internal medicine coronary care unit had the same RAPD pattern and were isolated within a 5-month period, suggesting that there was probable nosocomial spread within the same ward. Thus, the same or closely related isolates were identified repeatedly by PCR fingerprinting by RAPD analysis from five hospitals, suggesting the nosocomial spread of these organisms in each hospital. Furthermore, long-term cross-transmission of plasmids that carry MBL genes among different bacterial strains and species could result in the current complicated features of MBL producers, especially in hospital B.

The 2-MPA test, which is a simple test that was first described by Arakawa et al. (2), is a useful method for the routine laboratory detection of MBLs (45). Moreover, in the present study, all isolates that tested positive in the 2-MPA test were subsequently confirmed to be positive for the MBL gene by PCR. However, the growth inhibition zones of blaVIM-2-positive E. cloacae isolates were weak and ambiguous, possibly due to the excessive production of AmpC and/or a change in membrane permeability. The production of some extended-spectrum β-lactamases as well as the excessive production of the chromosomal AmpC cephalosporinase could be responsible for the characteristics of these strains that were previously reported for E. cloacae (2, 7). In such cases, imipenem and meropenem disks would be better than ceftazidime disks for the detection of MBL production because imipenem and meropenem are essentially not hydrolyzed by extended-spectrum β-lactamases and class C cephalosporinases.

With respect to antimicrobial susceptibilities, various β-lactam antimicrobial agents such as ureidopenicillin, cephalosporins, cephamycins, and carbapenems had high MICs for most MBL-positive isolates, whereas monobactam and piperacillin typically had low MICs for MBL producers. Low MICs of cefepime, meropenem, and imipenem were observed for several isolates, even though MBLs can hydrolyze these agents. The production of MBLs in these isolates could be cryptic or suppressed in strains showing low-level carbapenem resistance (14). It is also possible that IMP-3 and IMP-6 MBLs, which have low-level hydrolytic activities against these agents (15, 47), are produced in such isolates. The increased ability of active efflux systems and decreased outer membrane permeabilities have been reported to contribute to β-lactam resistance in P. aeruginosa (23, 24). Therefore, the low-level MICs of piperacillin, cefepime, and carbapenems for some isolates may be due to higher permeability coefficients or less efficient efflux pumps in the bacterial membranes in addition to the molecular mechanisms described above.

The MICs of monobactam and piperacillin for MBL producers were relatively low compared to those of oximinocephalosporins, cephamycins, and carbapenems (35, 36); however, this finding does not necessarily reflect their clinical efficacy against MBL producers because most gram-negative rods have the intrinsic ability to produce chromosomal AmpC cephalosporinases, which can hydrolyze monobactam and piperacillin (17). Although the administration of high doses of aztreonam or tazobactam-piperacillin was reported to be useful for the reduction of MBL-producing strains in rats suffering from experimental pneumonia (3), it is possible that the induction of intrinsic chromosomal AmpC production in MBL producers may promote the emergence of multiple-β-lactam-resistant gram-negative rods in clinical settings.

In the present study, MICs of tazobactam-piperacillin and cefoperazone-sulbactam were generally low for MBL-positive Acinetobacter isolates. Strains producing IMP-1 or VIM-2 usually show high-level resistance to oximinocephalosporins and cephamycins, but the MIC of piperacillin for these strains is usually lower than those of oximinocephalosporins and cephamycins (9, 30, 32). Because the activities of MBLs are not reduced significantly by β-lactamase inhibitors, such as sulbactam and tazobactam (5), the observations for Acinetobacter isolates suggested that the phenotypes related to these combination drugs may depend mainly on the intrinsic production of AmpC cephalosporinase (4, 10) as well as the low-level production of MBLs and alterations in membrane permeability. Thus, the low MIC levels of tazobactam-piperacillin and cefoperazone-sulbactam for MBL-producing Acinetobacter isolates could be an intrinsic feature of this bacterial genus.

In conclusion, plasmid-mediated MBL-producing gram-negative rods were first described approximately 13 years ago in Japan, and in the present study, such isolates were found to have disseminated to many hospitals in the Kinki region of Japan. It is conceivable that several isolates have spread nosocomially among a number of hospitals. The results of the present study should be considered when health care facilities develop policies and strategic practices to prevent and address the emergence and spread of MBL-producing gram-negative microorganisms in clinical environments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Bacterial Resistance Research Group in Kinki, Japan, and the genetic characterization of isolates was supported by grants from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan (H15-Shinkou-9 and H15-Shinkou-10).

The authors are all members of the Bacterial Resistance Research Group, Kinki, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arakawa, Y., M. Murakami, K. Suzuki, H. Ito, R. Wacharotayankun, S. Ohtuka, N. Kato, and M. Ohta. 1995. A novel integron-like element carrying the metallo-β-lactamase gene blaIMP. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1612-1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arakawa, Y., N. Shibata, K. Shibayama, H. Kurokawa, T. Yagi, H. Fujiwara, and M. Goto. 2000. Convenient test for screening metallo-β-lactamase-producing gram-negative bacteria by using thiol compounds. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:40-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellais, S., O. Mimoz, S. Leotard, A. Jacolot, O. Petitjean, and P. Nordmann. 2002. Efficacy of β-lactams for treating experimentally induced pneumonia due to a carbapenem-hydrolyzing metallo-β-lactamase-producing strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2032-2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bello, H., M. Dominguez, G. Gonzalez, R. Zemelman, S. Mella, H. K. Young, and S. G. Amyes. 2000. In vitro activities of ampicillin, sulbactam and a combination of ampicillin and sulbactam against isolates of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex isolated in Chile between 1990 and 1998. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45:712-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bush, K., C. Macalintal, B. A. Rasmussen, V. J. Lee, and Y. Yang. 1993. Kinetic interactions of tazobactam with β-lactamase from all major structural classes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:851-858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell, M., E. Mahenthiralingam, and D. P. Speert. 2000. Evaluation of random amplified polymorphic DNA typing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4614-4615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardoso, O., R. Leitao, A. Figueiredo, J. C. Sousa, A. Duarte, and L. V. Peixe. 2002. Metallo-β-lactamase VIM-2 in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Portugal. Microb. Drug Resist. 8:93-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornaglia, G., A. Mazzariol, L. Lauretti, G. M. Rossolini, and R. Fontana. 2000. Hospital outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing VIM-1, a novel transferable metallo-β-lactamase. Clin. Infect. Dis. 31:1119-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Docquier, J. D., J. Lamotte-Brasseur, M. Galleni, G. Amicosante, J. M. Frere, and G. M. Rossolini. 2003. On functional and structural heterogeneity of VIM-type metallo-β-lactamases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:257-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eliopoulos, G. M., K. Klimm, M. J. Ferraro, G. A. Jacoby, and R. C. Moellering. 1989. Comparative in vitro activity of piperacillin combined with the β-lactamase inhibitor tazobactam (YTR 830). Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 12:481-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gales, A. C., L. C. Menezes, S. Silbert, and H. S. Sader. 2003. Dissemination in distinct Brazilian regions of an epidemic carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing SPM metallo-beta-lactamase. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:699-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hejazi, A., C. T. Keane, and F. R. Falkiner. 1997. The use of RAPD-PCR as a typing method for Serratia marcescens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:913-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirakata, Y., K. Izumikawa, T. Yamaguchi, H. Takemura, H. Tanaka, R. Yoshida, J. Matsuda, M. Nakano, K. Tomono, S. Maesaki, M. Kaku, Y. Yamada, S. Kamihira, and S. Kohno. 1998. Rapid detection and evaluation of clinical characteristics of emerging multiple-drug-resistant gram-negative rods carrying the metallo-β-lactamase gene blaIMP. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2006-2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito, H., Y. Arakawa, S. Ohsuka, R. Wacharotayankun, N. Kato, and M. Ohta. 1995. Plasmid-mediated dissemination of the metallo-β-lactamase gene blaIMP among clinically isolated strains of Serratia marcescens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:824-829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iyobe, S., H. Kusadokoro, J. Ozaki, N. Matsumura, S. Minami, S. Haruta, T. Sawai, and K. O'Hara. 2000. Amino acid substitutions in a variant of IMP-1 metallo-β-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2023-2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iyobe, S., H. Kusadokoro, A. Takahashi, S. Yomoda, T. Okubo, A. Nakamura, and K. O'Hara. 2002. Detection of a variant metallo-β-lactamase, IMP-10, from two unrelated strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and an Alcaligenes xylosoxidans strain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2014-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones, R. N. 1998. Important and emerging β-lactamase-mediated resistances in hospital-based pathogens: the Amp C enzymes. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 31:461-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koh, T. H., G. S. Babini, N. Woodford, L. H. Sng, L. M. Hall, and D. Livermore. 1999. Carbapenem-hydrolysing IMP-1 β-lactamase in Klebsiella pneumoniae from Singapore. Lancet 353:2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurokawa, H., T. Yagi, N. Shibata, K. Shibayama, and Y. Arakawa. 1999. Worldwide proliferation of carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria. Lancet 354:955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laraki, N., N. Franceschini, G. M. Rossolini, P. Santucci, C. Meunier, E. Pauw, G. Amicosante, J. M. Frere, and M. Galleni. 1999. Biochemical characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa 101/1477 metallo-β-lactamase IMP-1 produced by Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:902-906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lauretti, L., M. L. Riccio, A. Mazzariol, G. Cornaglia, G. Amicosante, R. Fontana, and G. M. Rossolini. 1999. Cloning and characterization of blaVIM, a new integron-borne metallo-β-lactamase gene from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1584-1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, K., J. B. Lim, J. H. Yum, D. Yong, Y. Chong, J. Kim, and D. M. Livermore. 2002. blaVIM-2 cassette-containing novel integrons in metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas putida isolates disseminated in a Korean hospital. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1053-1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, X. Z., D. Ma, D. M. Livermore, and H. Nikaido. 1994. Role of efflux pump(s) in intrinsic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: active efflux as a contributing factor to β-lactam resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1742-1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsumura, N., S. Minami, Y. Watanabe, S. Iyobe, and S. Mitsuhashi. 1999. Role of permeability in the activities of β-lactams against gram-negative bacteria which produce a group 3 β-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2084-2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mavroidi, A., A. Tsakris, E. Tzelepi, S. Pournaras, V. Loukova, and L. S. Tzouvelekis. 2000. Carbapenem-hydrolysing VIM-2 metallo-β-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Greece. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:1041-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 4th ed. Approved standard M7-A4. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 27.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests, 6th ed. Approved standard M2-A6. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 28.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Tenth informational supplement, M100-S10. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 29.Olive, D. M., and P. Bean. 1999. Principles and applications of methods for DNA-based typing of microbial organisms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1661-1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osano, E., Y. Arakawa, R. Wacharotayankun, M. Ohta, T. Horii, H. Ito, F. Yoshimura, and N. Kato. 1994. Molecular characterization of an enterobacterial metallo-β-lactamase found in a clinical isolate of Serratia marcescens that shows imipenem resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:71-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ploy, M. C., F. Denis, P. Courvalin, and T. Lambert. 2000. Molecular characterization of integrons in Acinetobacter baumannii: description of a hybrid class 2 integron. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2684-2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poirel, L., T. Naas, D. Nicolas, L. Collet, S. Bellais, J. D. Cavallo, and P. Nordmann. 2000. Characterization of VIM2, a carbapenem-hydrolyzing metallo-β-lactamase and its plasmid- and integron-borne gene from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate in France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:891-897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riccio, M. L., N. Franceschini, L. Boschi, B. Caravelli, G. Cornaglia, R. Fontana, G. Amicosante, and G. M. Rossolini. 2000. Characterization of the metallo-β-lactamase determinant of Acinetobacter baumannii AC-54/97 reveals the existence of blaIMP allelic variants carried by gene cassettes of different phylogeny. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1229-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sasaki, T., T. Nishiyama, M. Shintani, and T. Kenri. 1997. Evaluation of a new method for identification of bacteria based on sequence homology of 16S rRNA gene. PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 51:242-247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senda, K., Y. Arakawa, S. Ichiyama, K. Nakashima, H. Ito, S. Ohsuka, K. Shimokata, N. Kato, and M. Ohta. 1996. PCR detection of metallo-β-lactamase gene (blaIMP) in gram-negative rods resistant to broad-spectrum β-lactamases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2909-2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Senda, K., Y. Arakawa, K. Nakashima, H. Ito, S. Ichiyama, K. Shimokata, N. Kato, and M. Ohta. 1996. Multifocal outbreaks of metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistant to broad-spectrum β-lactams, including carbapenems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:349-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shibata, N., Y. Doi, K. Yamane, T. Yagi, H. Kurokawa, K. Shibayama, H. Kato, K. Kai, and Y. Arakawa. 2003. PCR typing of genetic determinants for metallo-β-lactamases and integrases carried by gram-negative bacteria isolated in Japan with focus on the class 3 integron. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5407-5413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takahashi, A., S. Yomoda, I. Kobayashi, T. Okubo, M. Tsunoda, and S. Iyobe. 2000. Detection of carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in a hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:526-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toleman, M. A., A. M. Simm, T. A. Murphy, A. C. Gales, D. J. Biedenbach, R. N. Jones, and T. R. Walsh. 2002. Molecular characterization of SPM-1, a novel metallo-β-lactamase isolated in Latin America: report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:673-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsakris, A., S. Pournaras, N. Woodford, M. F. Palepou, G. S. Babini, J. Douboyas, and D. M. Livermore. 2000. Outbreak of infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing VIM-1 carbapenemase in Greece. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1290-1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Versalovic, J., T. Koeuth, and J. R. Lupski. 1991. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:6823-6831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watanabe, M., S. Iyobe, M. Inoue, and S. Mitsuhashi. 1991. Transferable imipenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:147-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woodford, N., M. F. Palepou, G. S. Babini, J. Bates, and D. M. Livermore. 1998. Carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa in UK. Lancet 352:546-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamasaki, K., M. Komatsu, T. Yamashita, K. Shimakawa, T. Ura, H. Nishio, K. Satoh, R. Washidu, S. Kinoshita, and M. Aihara. 2003. Production of CTX-M-3 extended-spectrum β-lactamase and IMP-1 metallo-β-lactamase by five gram-negative bacilli: survey of clinical isolates from seven laboratories collected in 1998 and 2000, in the Kinki region of Japan. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:631-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yan, J. J., P. R. Hsueh, W. C. Ko, K. T. Luh, S. H. Tsai, H. M. Wu, and J. J. Wu. 2001. Metallo-β-lactamases in clinical Pseudomonas isolates in Taiwan and identification of VIM-3, a novel variant of the VIM-2 enzyme. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2224-2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yan, J. J., W. C. Ko, C. L. Chuang, and J. J. Wu. 2002. Metallo-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates in a university hospital in Taiwan: prevalence of IMP-8 in Enterobacter cloacae and first identification of VIM-2 in Citrobacter freundii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:503-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yano, H., A. Kuga, R. Okamoto, H. Kitasato, T. Kobayashi, and M. Inoue. 2001. Plasmid-encoded metallo-β-lactamase (IMP-6) conferring resistance to carbapenems, especially meropenem. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1343-1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]