Abstract

Multiple genotypically unique strains of the tick-borne pathogen Anaplasma marginale occur and are transmitted within regions where the organism is endemic. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that specific A. marginale strains are preferentially transmitted. The study herd of cattle (n = 261) had an infection prevalence of 29% as determined by competitive inhibition enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and PCR, with complete concordance between results of the two assays. Genotyping revealed the presence of 11 unique strains within the herd. Although the majority of the individuals (70 of 75) were infected with only a single A. marginale strain, five animals each carried two strains with markedly distinct genotypes, indicating that superinfection does occur with distinct A. marginale strains, as has been reported with A. marginale and A. marginale subsp. centrale strains. Identification of strains in animals born into and infected within the herd during the period from 1998 to 2003 revealed no significant difference from the overall strain prevalence in the herd, results that do not support the occurrence of preferential strain transmission within a population of persistently infected animals and are most consistent with pathogen strain transmission being stochastic.

Anaplasma marginale is the most globally prevalent tick-transmitted pathogen of livestock, with regions of endemicity on all six permanently populated continents (13). In North America, A. marginale exhibits dramatic strain diversity, with numerous distinct genotypes having been identified in the past 15 years (1, 5, 6, 8, 14). As A. marginale is not passed transovarially in the tick and thus cannot be maintained between generations, transmission requires the presence of infected mammalian reservoir hosts (12, 17). Consequently, the presence of multiple distinct strains within the population of infected reservoir hosts provides potential diversity for transmission. A previous study in a region of eastern Oregon where the organism is endemic identified six closely genetically related A. marginale strains within a herd of persistently infected cattle, an observation consistent with ongoing transmission of multiple strains within the herd (14). Independent transmission of multiple strains within a herd is supported by the isolation of distinct A. marginale strains, each from an individual cow with acute anaplasmosis, within a period of several months (7). It is unknown whether transmission of a specific A. marginale strain is stochastic, merely reflecting the strain composition present in the herd, or whether there is preferential transmission of specific strains. The identification of both qualitative (transmissible or not by a specific tick vector) and quantitative (strain-specific differences in the number of organisms per infected tick) differences in transmissibility among A. marginale strains provides a basis for preferential transmission (2, 9, 16, 19).

To test the hypothesis that specific A. marginale strains are preferentially transmitted within a herd with a high prevalence of infection, we analyzed the strain composition in 75 animals born from 1990 to 1999 and subsequently infected with A. marginale within the herd. The study herd was located at Kansas State University and contained 261 cows selected for initial screening. All of the cows in the present study were born into this herd and remained within the herd for the duration of the study; all blood samples used for determination of prevalence and identification of strain genotype were collected in early spring prior to the transmission season. Initially, 75 animals were identified as infected with A. marginale with the MSP5 competitive inhibition enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (CI-ELISA) (11, 18). All 75 seropositive animals were subsequently shown to be A. marginale PCR positive by using msp5- or msp1α-specific primers with genomic DNA extracted from whole blood collected in heparin, procedures previously described in detail (9, 14, 18). Thus, A. marginale prevalence within the herd was 29%, and there was 100% concordance between MSP5 CI-ELISA serology and the PCR assays. The A. marginale genotype was determined by sequencing the msp1α gene and identifying the number and sequence of the 84- or 87-bp repeats in the 5′ region of the gene. Briefly, primers in the conserved regions flanking the strain-specific repeat region of msp1α (forward, 5′-GTGCTTATGGCAGACATTTCC-3′; reverse, 5′-CTCAACACTCGCAACCTTGG-3′) were used in PCR amplification as previously described (14). Amplified fragments were identified by agarose gel electrophoresis and cloned into PCR-4 TOPO vector using the TOPO-TA cloning kit (Invitrogen), and TOP10 Escherichia coli competent cells were transformed. If more than a single amplicon was detected, the amplicons were excised and cloned individually. Plasmid DNA was isolated from individual transformed colonies, the presence of the predicted insert was confirmed by EcoRI digestion, and inserts were sequenced in both directions with a Big Dye kit and an ABI 3100 Prism automated sequencer. Sequences were compiled by using VECTOR NTI (InforMax). Genotypes were reported by using the convention of Allred et al. (1), in which each unique repeat type is designated by a letter, A to Z or α to φ. Repeat types A to E were reported by Allred et al. (1); types F to J were reported by Palmer et al. (14); types K to V were reported by de la Fuente et al. (4); type Z was reported by Futse et al. (9); and types α to φ were reported by Garcia-Garcia et al. (10).

A msp1α genotype was obtained from each of the 75 persistently infected cows (Table 1). That the genotype identified by PCR amplification and sequencing represents the true msp1α genotype is supported by three lines of evidence: (i) each sequence differed only in the number and sequence of repeats, with no changes in the nucleotide sequence or reading frame of the flanking 5′ and 3′ regions, which are highly conserved (1); (ii) 10 samples were reextracted, amplified, and sequenced, with the identical sequence being obtained from the independent replicates; and (iii) the size of the msp1α repeat region was determined by EcoRII digestion and Southern blotting, excluding possible addition or loss of repeats during PCR amplification. For verification using Southern blotting, three distinct A. marginale strains, with genotypes EMφ, BBBBBB, and DDDDDDE, were isolated by inoculation of 10 ml of blood obtained from persistently infected cows (animal numbers 3201, 9038, and 8416) into each of three MSP5 CI-ELISA seronegative, msp5 PCR negative, splenectomized calves. Each of the calves developed acute A. marginale bacteremia, and blood with bacteremia levels of ≥109 organisms per ml was collected. Total DNA was PCR amplified, and the msp1α genotype was determined by sequencing as described above. Each of the A. marginale genotype sequences obtained from the inoculated calves was identical to that of the strain from persistently infected cows. For Southern blotting, nonamplified genomic DNA isolated from the blood of each calf at peak A. marginale bacteremia was digested with EcoRII and hybridized with a digoxigenin-labeled msp1α probe spanning the repeat region (14). The probe was generated by PCR using the primers 5′-CATTTCCATATACTGTGCAG and 5′-CTTGGAGCGCATCTCTCTTGCC and the PCR probe synthesis kit (Roche). The EcoRII sites in msp1α are external to the repeat region and thus can be used to provide an independent estimate of the number of 84- to 87-bp repeats (14). The EMφ genotype, with three repeats; the BBBBBB genotype, with six repeats; and the DDDDDDE genotype, with seven repeats, contained the predicted EcoRII repeat region fragments of 743 bp, 1,044 bp, and 1,091 bp, respectively (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Distribution of A. marginale msp1α genotypes within the herd

| Animal | ELISA | PCR | msp1α genotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3261 | + | + | BB |

| 8082 | + | + | BB |

| 4102 | + | + | BBB |

| 2267 | + | + | BBBB |

| 7304 | + | + | BBBB |

| 8405 | + | + | BBBB |

| 0141 | + | + | BBBBB |

| 4087 | + | + | BBBBB |

| 4107 | + | + | BBBBB |

| 5008 | + | + | BBBBB |

| 6055 | + | + | BBBBB |

| 7072 | + | + | BBBBB |

| 0063 | + | + | BBBBBB |

| 1256 | + | + | BBBBBB |

| 9032 | + | + | BBBBBB |

| 9038 | + | + | BBBBBB |

| 5076 | + | + | DDDDD |

| 7042 | + | + | DDE |

| 4318 | + | + | DDDDDE |

| 2070 | + | + | DDDDDDE |

| 6206 | + | + | DDDDDDE |

| 7175 | + | + | DDDDDDE |

| 8078 | + | + | DDDDDDE |

| 8416 | + | + | DDDDDDE |

| 9060 | + | + | DDDDDDE |

| 9514 | + | + | DDDDDDE |

| 7030 | + | + | DDDDDDDDDE |

| 0050 | + | + | EMφ |

| 0435 | + | + | EMφ |

| 1006 | + | + | EMφ |

| 1021 | + | + | EMφ |

| 1026 | + | + | EMφ |

| 1030 | + | + | EMφ |

| 1039 | + | + | EMφ |

| 2079 | + | + | EMφ |

| 2088 | + | + | EMφ |

| 2206 | + | + | EMφ |

| 3062 | + | + | EMφ |

| 3201 | + | + | EMφ |

| 4084 | + | + | EMφ |

| 4309 | + | + | EMφ |

| 3293 | + | + | EMφ |

| 4503 | + | + | EMφ |

| 5077 | + | + | EMφ |

| 5086 | + | + | EMφ |

| 5306 | + | + | EMφ |

| 5333 | + | + | EMφ |

| 6009 | + | + | EMφ |

| 6103 | + | + | EMφ |

| 6118 | + | + | EMφ |

| 6177 | + | + | EMφ |

| 6192 | + | + | EMφ |

| 7035 | + | + | EMφ |

| 7079 | + | + | EMφ |

| 7181 | + | + | EMφ |

| 7211 | + | + | EMφ |

| 7264 | + | + | EMφ |

| 7285 | + | + | EMφ |

| 7306 | + | + | EMφ; BBBBB |

| 7332 | + | + | EMφ |

| 8001 | + | + | EMφ |

| 8002 | + | + | EMφ |

| 8028 | + | + | EMφ |

| 8059 | + | + | EMφ |

| 8219 | + | + | EMφ |

| 8261 | + | + | EMφ |

| 8308 | + | + | EMφ |

| 8414 | + | + | EMφ |

| 8918 | + | + | EMφ |

| 9012 | + | + | EMφ |

| 9031 | + | + | EMφ |

| 9061 | + | + | EMφ; BBBB |

| 1024 | + | + | EMφ; DDDDDDE |

| 1027 | + | + | EMφ; DDDDDDE |

| 9060 | + | + | EMφ; DDDDDDE |

FIG. 1.

Southern blot confirmation of the msp1α repeat structure predicted by amplicon size and sequence. DNA extracted from animals 3201 (EMφ genotype), 9038 (BBBBBB genotype), and 8416 (DDDDDDE genotype) was EcoRII digested and Southern blotted using an msp1α probe. Arrows on the right designate the predicted sizes for the internal EcoRII fragments of msp1α for each genotype, and the positions of the molecular size markers are indicated on the left.

Eleven distinct A. marginale msp1α genotypes were detected from the 75 persistently infected animals (Table 1). While this is the most genotypic diversity yet reported within a single herd, it is consistent with previous studies reporting the presence and transmission of multiple distinct genotypes within herds in regions where the organism is endemic (7, 14). Interestingly, the 11 genotypes separated into three families: EMφ, which contained a single genotype; Bx, which contained five separate genotypes with two to six B-sequence repeats; and D/E, which contained five genotypes defined by a series of two to nine D repeats with or without a terminal E repeat sequence (Table 1). The presence of closely related genotypes, exemplified by the latter two families, Bx and D/E, has previously been detected within a herd with a high prevalence of infection in eastern Oregon (14). However, that herd differed from the one in the present study in that all of the detected genotypes were closely related rather than segregated into distinct families. While it is presumed that these closely related genotypes are evolutionarily derived from one another or a common parent strain, tracking of genotypes during long-term persistent infections in the mammalian reservoir and through the cycle of tick transmission has failed to detect genotypic changes, suggesting that the rate of change and/or selection is relatively low (14).

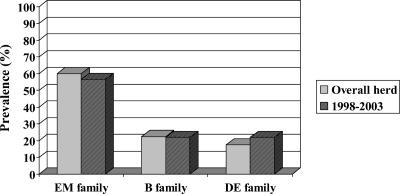

The hypothesis that preferential strain transmission occurs would be supported by the detection of specific genotypes, or a family of genotypes, in calves born into and infected within the herd. Examination of 20 infected animals born after 1998 revealed the presence of each of the three families of genotypes, with a total of six individual genotypes. There was no statistically significant difference in genotype frequency between the herd population and the calves born into and infected within the herd (Fig. 2), as tested by using analysis of variance followed by determination of Fisher's least significant difference using a P value of ≤0.05 for significance. Thus, A. marginale genotypes in each of the three families are being maintained within the herd by ongoing transmission. The data do not support the hypothesis of preferential strain transmission and appear most consistent with transmission being stochastic relative to genotype frequency. This result may reflect equal transmission efficiency of the different strains by ticks or, alternatively, mechanical transmission that does not require A. marginale invasion and replication in a vector and would be predicted to reflect genotype frequency. However, an important caveat should be noted; the conclusion of stochastic transmission is limited to ongoing transmission within a herd with a high prevalence of infection, and whether this conclusion applies to disease outbreaks when widespread transmission to and within a population of naïve animals occurs is unknown. Characterization of A. marginale strains isolated from each of 10 sick animals during an acute outbreak revealed complete homogeneity in the msp1α genotypes (14).

FIG. 2.

Anaplasma marginale genotype prevalence in the herd and in animals born into and infected within the herd from 1998 to 2003.

Prior studies of herds naturally infected with A. marginale and with experimental A. marginale infections have indicated that individual animals are infected with only a single msp1α genotypically defined strain (3, 7, 14). The present study is the first to identify superinfection with two A. marginale strains; five animals (1024, 1027, 7306, 9060, and 9061) were each infected with two distinct genotypes. Interestingly, the two genotypes present represent different families: EMφ and D/E were present in animals 1024, 1027, and 9060; and EMφ and Bx were present in animals 7306 and 9061. While superinfection with A. marginale strains with closely related msp1α genotypes remains unreported, whether this reflects a true lack of occurrence or the detection of only a predominant genotype, with very low levels of a second genotype remaining undetected, is unknown. A. marginale superinfection is common in animals deliberately infected (live strain vaccination) with A. marginale subsp. centrale. Within a region where the organism is endemic, 64% of cattle inoculated with the live A. marginale subsp. centrale vaccine strain were subsequently infected by natural transmission of A. marginale and harbored both organisms (15). The basis for this marked difference between the relatively high frequency of superinfection observed following live vaccination and the low frequency in natural transmission within herds with high infection prevalence is unknown, although it may well be related to genetic distance and corresponding antigenic differences among the subspecies and strains. Resolving this question will require integrating studies of strain transmission with antigenic characterization of the strains and the epitope specificity of the immune responses elicited during infection.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH R01 AI44005, USDA-ARS-CRIS 5348-32000-016-00D, and USDA-ARS Cooperative Agreement 58-5348-3-212.

The technical assistance of Peter Hetrick, Carter Hoffman, Ralph Horn, and Bev Hunter is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allred, D. R., T. C. McGuire, G. H. Palmer, S. R. Leib, T. M. Harkins, T. F. McElwain, and A. F. Barbet. 1990. Molecular basis for surface antigen size polymorphisms and conservation of a neutralization-sensitive epitope in Anaplasma marginale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:3220-3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de la Fuente, J., J. C. Garcia-Garcia, E. F. Blouin, B. R. McEwen, D. Clawson, and K. M. Kocan. 2001. Major surface protein 1a effects tick infection and transmission of Anaplasma marginale. Int. J. Parasitol. 31:1705-1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de la Fuente, J., J. C. Garcia-Garcia, E. F. Blouin, J. T. Saliki, and K. M. Kocan. 2002. Infection of tick cells and bovine erythrocytes with one genotype of the intracellular ehrlichia Anaplasma marginale excludes infection with other genotypes. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 9:658-668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de La Fuente, J., E. J. Golsteyn Thomas, R. A. Van Den Bussche, R. G. Hamilton, E. E. Tanaka, S. E. Druhan, and K. M. Kocan. 2003. Characterization of Anaplasma marginale isolated from North American bison. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5001-5005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de la Fuente, J., R. A. Van Den Bussche, J. C. Garcia-Garcia, S. D. Rodriguez, M. A. Garcia, A. A. Guglielmone, A. J. Mangold, L. M. Friche Passos, M. F. Barbosa Ribeiro, E. F. Blouin, and K. M. Kocan. 2002. Phylogeography of New World isolates of Anaplasma marginale based on major surface protein sequences. Vet. Microbiol. 88:275-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de la Fuente, J., R. A. Van Den Bussche, and K. M. Kocan. 2001. Molecular phylogeny and biogeography of North American isolates of Anaplasma marginale (Rickettsiaceae: Ehrlichieae). Vet. Parasitol. 97:65-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de la Fuente, J., R. A. Van Den Bussche, T. M. Prado, and K. M. Kocan. 2003. Anaplasma marginale msp1α genotypes evolved under positive selection pressure but are not markers for geographic isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1609-1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eriks, I. S., D. Stiller, W. L. Goff, M. Panton, S. M. Parish, T. F. McElwain, and G. H. Palmer. 1994. Molecular and biological characterization of a newly isolated Anaplasma marginale strain. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 6:435-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Futse, J. E., M. W. Ueti, D. P. Knowles, Jr., and G. H. Palmer. 2003. Transmission of Anaplasma marginale by Boophilus microplus: retention of vector competence in the absence of vector-pathogen interaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3829-3834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia-Garcia, J. C., J. de la Fuente, G. Bell-Eunice, E. F. Blouin, and K. M. Kocan. 2004. Glycosylation of Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 1a and its putative role in adhesion to tick cells. Infect. Immun. 72:3022-3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knowles, D., S. Torioni de Echaide, G. Palmer, T. McGuire, D. Stiller, and T. McElwain. 1996. Antibody against an Anaplasma marginale MSP5 epitope common to tick and erythrocyte stages identifies persistently infected cattle. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2225-2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kocan, K. M., J. A. Hair, S. A. Ewing, and L. G. Stratton. 1981. Transmission of Anaplasma marginale Theiler by Dermacentor andersoni Stiles and Dermacentor variabilis (Say). Am. J. Vet. Res. 42:15-18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmer, G. H., F. R. Rurangirwa, K. M. Kocan, and W. C. Brown. 1999. Molecular basis for vaccine development against the ehrlichial pathogen Anaplasma marginale. Parasitol. Today 15:281-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmer, G. H., F. R. Rurangirwa, and T. F. McElwain. 2001. Strain composition of the ehrlichia Anaplasma marginale within persistently infected cattle, a mammalian reservoir for tick transmission. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:631-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shkap, V., T. Molad, L. Fish, and G. H. Palmer. 2002. Detection of the Anaplasma centrale vaccine strain and specific differentiation from Anaplasma marginale in vaccinated and infected cattle. Parasitol. Res. 88:546-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith, R. D., M. G. Levy, M. S. Kuhlenschmidt, J. H. Adams, D. L. Rzechula, T. A. Hardt, and K. M. Kocan. 1986. Isolate of Anaplasma marginale not transmitted by ticks. Am. J. Vet. Res. 47:127-129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stich, R. W., K. M. Kocan, G. H. Palmer, S. A. Ewing, J. A. Hair, and S. J. Barron. 1989. Transstadial and attempted transovarial transmission of Anaplasma marginale by Dermacentor variabilis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 50:1377-1380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torioni de Echaide, S., D. P. Knowles, T. C. McGuire, G. H. Palmer, C. E. Suarez, and T. F. McElwain. 1998. Detection of cattle naturally infected with Anaplasma marginale in a region of endemicity by nested PCR and a competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using recombinant major surface protein 5. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:777-782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wickwire, K. B., K. M. Kocan, S. J. Barron, S. A. Ewing, R. D. Smith, and J. A. Hair. 1987. Infectivity of three Anaplasma marginale isolates for Dermacentor andersoni. Am. J. Vet. Res. 48:96-99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]