Abstract

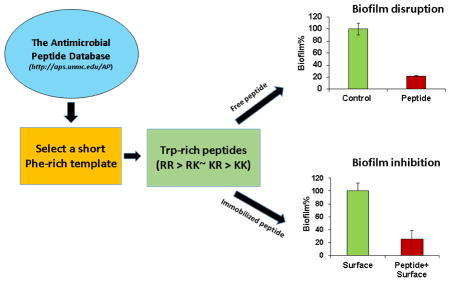

Short antimicrobial peptides are essential to keep us healthy and their lasting potency can inspire the design of new types of antibiotics. This study reports the design of a family of eight-residue tryptophan-rich peptides (TetraF2W) obtained by converting the four phenylalanines in temporin-SHf to tryptophans. The temporin-SHf template was identified from the antimicrobial peptide database (http://aps.unmc.edu/AP). Remarkably, the double arginine variant (TetraF2W-RR) was more effective in killing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) USA300, but less cytotoxic to human skin HaCat and kidney HEK293 cells, than the lysine-containing dibasic combinations (KR, RK and KK). Killing kinetics and fluorescence spectroscopy suggest membrane targeting of TetraF2W-RR, making it more difficult for bacteria to develop resistance. Because established biofilms on medical devices are difficult to remove, we chose to covalently immobilize TetraF2W-RR onto the polyethylene terephthalate (PET) surface to prevent biofilm formation. The successful surface coating of the peptide is supported by FT-IR and XPS spectroscopies, chemical quantification, and antibacterial assays. This peptide-coated surface indeed prevented S. aureus biofilm formation with no cytotoxicity to human cells. In conclusion, TetraF2W-RR is a short Trp-rich peptide with demonstrated antimicrobial and anti-biofilm potency against MRSA in both the free and immobilized forms. Because these short peptides can be synthesized cost effectively, they may be developed into new antimicrobial agents or used as surface coating compounds.

Keywords: Anti-biofilm peptides, biofilms, MRSA, surface immobilization, Trp-rich peptides

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

In 1928, Alexander Fleming serendipitously discovered penicillin. This discovery opened the golden age of modern antibiotics [1]. However, a resistant staphylococcal strain was identified only four years after the large-scale production of penicillin in the 1940s. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains that are resistant to multiple antibiotics first appeared in clinical settings. Subsequently, resistant Staphylococcal strains were also isolated from the communities [2, 3]. MRSA infections can cause life-threatening endocarditis, pneumonia, septicemia, septic arthritis, and osteomyelitis. The community-associated MRSA USA300 strain is responsible for the majority of the skin and soft tissue infection [4]. It is stunning that the total deaths due to MRSA infections are comparable to the deaths caused by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) [5, 6]. As a consequence, novel therapeutic compounds are urgently needed to control MRSA.

Natural antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are host defense molecules identified in various organisms ranging from bacteria to humans. The majority of these molecules contain 10–50 amino acids with net charges 0 – +7 and hydrophobic contents 31–70% [7, 8]. AMPs can rapidly kill invading pathogens by disrupting membranes, rendering it difficult for pathogens to develop resistance. Moreover, multiple types of AMPs could be expressed in humans to control pathogens by different mechanisms [9]. In addition, these molecules can also regulate immune responses. All these properties made them appealing candidates for developing new therapies.

There is a high interest in linear AMPs because such peptides can be readily synthesized. Previously, we attempted to define the minimal sequence requirements for helical AMPs. We found it possible to convert a 10-residue non-toxic bacterial membrane anchor to a 13-residue antibacterial peptide by extending the helix [10]. We also identified KR-12 corresponding to the minimal antimicrobial region of human cathelicidin LL-37 based on NMR structural studies [11, 12]. Interestingly, we also obtained 13-residue peptides against methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) with in vitro and in vivo efficacy based on the antimicrobial peptide database (APD) [13, 14]. These results imply that approximately 12–13 residues are required for helical AMPs.

This study intends to design even shorter peptides (< 10 amino acids) as a template for developing alternative antibiotics or antibiofilm surfaces. This is because a short peptide can be made cost effectively. In addition, shorter peptides contain less units to optimize, reducing the R & D cost for industry. We first identified a short peptide template with the aid of the APD database [8]. The temporin-SHf template possesses the highest phenylalanine content with moderate activity against MRSA [15]. To enhance the peptide activity, we hypothesize that replacements of four phenylalanines (F) in temporin-SHf with tryptophans (W) will achieve this goal because tryptophans are known to prefer membrane interfaces [16–18]. Based on these four replacements, the new peptide family is named as TetraF2W. Among the series of peptides designed, TetraF2W-RR with a pair of arginines shows higher activity against MRSA USA300 than other lysine-containing analogs. Interestingly, the double arginine peptide is less cytotoxic to human skin and kidney cells. In addition, it is possible to covalently immobilize the most potent peptide to the polyethylene terephthalate (PET) surface, opening another possible use of these short peptides in preventing biofilm formation on medical devices where different microbes may exist in the same community.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals, peptides and surfaces

All the peptides in this study were chemically synthesized and purified to >95% (Genemed Synthesis, TX). The peptide used for surface immobilization was >90% pure. Peptides were solubilized in distilled water and their concentrations were determined by UV spectroscopy based on the Trp absorbance at 280 nm [19]. The PET surfaces were purchased from Goodfellow Corporation (PA, USA). All chemicals used in the immobilization were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma (MO, USA) unless specified.

2.2. HPLC retention time measurements

The retention time of the peptide was measured on a Waters HPLC system equipped with an analytical reverse-phase Vydac C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm). The peptide detected at 220 and 280 nm was eluted with a gradient of acetonitrile (containing 0.1% TFA) from 5% to 95% at a flow rate of 1 mL/min [14].

2.3. Peptide parameter calculations

Peptide molecular weight, net charge, hydrophobic content, and Boman index were calculated using the prediction tool of the APD [8].

2.4. Bacterial strains

The bacterial strains used here included Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus USA300 LAC, Staphylococcus epidermidis 1457, Bacillus subtilis 168, and Gram-negative Escherichia coli K12. Clinical strains of S. aureus, including Mu50, UAMS-1 and Newman, were also evaluated.

2.5. Antibacterial assays

The antimicrobial activity of peptides was evaluated using a standard broth microdilution protocol as described previously [12]. In brief, exponential phase bacteria at 106 CFU were incubated with serially diluted peptides overnight for ~20 h at 37°C. The plates were read on a ChroMate 4300 Microplate Reader at 630 nm (GMI, Ramsey, MN). The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest peptide concentration that fully inhibited bacterial growth. In addition, the effects of human serum (up to 10%), pH (6.8, 7.4 and 8.0) and 150 mM sodium chloride (NaCl) on MICs against S. aureus USA300 were also evaluated as described [20].

The minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) was determined by plating 50 μl of the content in the clear wells of the above MIC assays. MBC was determined on the petri dishes without bacterial colony formation after overnight growth [21].

2.6. Killing kinetics

Killing kinetic experiments were conducted similar to antibacterial assays described above with the following modifications [22]. Aliquots of cultures (105 CFU) treated with TetraF2W peptides were taken at 15, 30, 50, 90, and 120 min, diluted 100-fold, and plated on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates. Colonies were counted after overnight incubation at 37°C.

2.7. Membrane permeation measurements

Fluorescence spectroscopy was also used to follow bacterial killing. In brief, a serially diluted 10× peptide (10 μL) was made in 96-well corning COSTAR microtiter plates. Propidium iodide (2 μL) was added at 50 μM to each well which was finally incubated with S. aureus USA300 bacteria (88 μL at a final OD600 ~0.1) with continuous shaking at 100 rpm, 37°C in a FLUOstar Omega (BMG LABTECH Inc, NC, USA) microplate reader. The plates were read every 5 minutes for a total duration of 2 h with excitation and emission wavelengths at 584 nm and 620 nm respectively. Plots were made using averaged readings from duplicated experiments after subtraction of the media control.

2.8. Confocal laser scanning microscopy

We also followed the entrance of a fluorescent dye into live bacterial cells by confocal microscopy [20]. In brief, S. aureus USA300 was grown to the exponential phase from the overnight culture. The cells were then washed twice with fresh 1× PBS (pH 7.2) and the final cell density was adjusted to 1 × 108 CFU/mL. 1500 μL of the culture was added to the chambers of cuvettes (Borosilicate cover glass systems) with equimolar concentrations of TetraF2W-RK and fluorescein isothiocyanate FITC (9 μM). The samples were examined with a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss 710) with live time series of picture taken every 5 seconds for 5 min and the data were processed using Zen 2010 software.

2.9. Anti-biofilm assays

Three types of experiments were conducted to evaluate the anti-biofilm activity of these peptides against S. aureus USA300, which was grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) media in flat bottom, 96-well, polystyrene microtiter plates [20, 23].

2.9.1. Inhibition of bacterial attachment

The first experiment measures the ability of the peptide to inhibit bacterial attachment, the initial step for biofilm formation. In short, overnight cultures of S. aureus USA300 were grown in TSB media to an optical density (600 nm) of ~1.0. 180 μL of this culture was added to each well of the microtiter plates containing 20 μL of 10× peptide solution. The plates are then incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Media with bacteria were then pipetted out and chambers were washed with 1× PBS to remove non-adherent cells. The inhibition of biofilms was estimated by XTT [2,3-bis(2-methyloxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tertazolium-5-carboxanilide] assay by following the manufacturer’s instructions with modifications. 180 μL of fresh TSB and 20 μL of XTT solution was added to each well and the plates were again incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Absorbance at 450 nm (only media with XTT containing wells served as the blank) was obtained using a ChromateTM microtiter plate reader. Percentage of biofilm mass for the peptide was plotted assuming 100% biofilm growth is achieved on the bacterial wells without peptide treatment.

2.9.2. Inhibition of biofilm growth

The second experiment evaluates the ability of the peptide to inhibit biofilm formation of S. aureus USA300 in 24 h. In brief, S. aureus USA300 (105 CFU/mL) was made in fresh TSB media from exponentially growing bacteria. 180 μL of this bacterial culture was added to each well of the microtiter plates containing 20 μL of 10× peptide solution. The plates were then incubated at 37°C for 24 h and inhibition of the biofilm formation by the peptides was quantitated using XTT as detailed above.

2.9.3. Preformed biofilm disruption

The third experiment evaluates the ability of the peptide to disrupt the biofilms of S. aureus USA300 formed in 24 h. S. aureus USA300 (105 CFU/mL) in fresh TSB media was made from an exponentially growing culture. 200 μL of this bacterial culture was added to each well of the microtiter plates. The plates are then incubated at 37°C for 24 h to allow biofilm formation. Media was then carefully removed followed by washing with sterile 1×PBS to remove any unattached bacteria. Solution containing 20 μL of 10× peptide solution and 180 μL of fresh TSB were added. The plates were again incubated at 37°C for another 24 h. The extent of peptide disruption of biofilms was quantified using the same XTT method described above.

2.10. Confocal microscopy of biofilms in the absence and presence of peptides

S. aureus USA300 (105 CFU/mL) was made from exponentially growing bacteria. 1800 μL was added to the chamber of cuvettes (Borosilicate cover glass systems, and was incubated for 37°C, 24 h for biofilm formation. Media was then pipetted out and chambers were washed with 1× PBS to remove non-adhered cells. To disrupt the preformed biofilms, 200 μL of 10× stocks of the peptide was added followed by 1800 μL of TSB. Control cuvettes contained water instead of peptide. The cuvettes were again incubated for another 24 h at 37°C. Subsequently, the supernatant was pipetted out and the chambers were washed with 1× PBS. For evaluation under confocal microscope the biofilms were stained with 10 μL of LIVE/DEAD kit (Invitrogen Molecular Probes, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were examined with a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss 710) and the data processed using Zen 2010 software.

2.11. Peptide cytotoxicity

2.11.1. Antifungal assays

Fungal strains used in this study include Candida albicans ATCC 10231, C. glabrata ATCC 2001 and C. tropicalis ATCC 13803. The fungi were grown in Remel Dex broth (Thermo Fisher Scientific, KS, USA). Antifungal assays were conducted essentially as described for antibacterial assays above, except for a higher starting density at an OD600 0.02 and a longer incubation time of ~48 h prior to microplate reading [20].

2.11.2. Hemolytic assays using red blood cells of humans, chickens, pigs, and cattle

Hemolytic analysis of selected peptides was performed using an established protocol [20]. Briefly, human blood cells (UNMC Blood Bank) were washed three times with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and diluted to a 2% solution. After peptide treatment, incubation at 37°C for one hour, and centrifugation at 13,000 rpm, aliquots of the supernatant were transferred to a fresh 96-well microplate. To assess peptide cytotoxicity, the amount of hemoglobin released was measured at 545 nm. The percent lysis was calculated by assuming 100% release when human blood cells were treated with 1% Triton X-100, and 0% release when incubated with PBS buffer. The hemolytic assays using chicken, bovine, and porcine blood cells (Lampire Biological Laboratories, Inc.) were performed in the same manner.

2.11.3. Cytotoxicity assays using human HeLa, HEK293 and HaCaT cells

HeLa CCL-2 epithelial adenocarcinoma cells from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) were maintained in DMEM high glucose media with 4 mM L-glutamine (NyClone) and 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin (pen/strep) (Life Technologies), and 10% (v/v) inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (NyClone). Cells were grown in 5% CO2 at 37°C and were detached from the culturing dish at 80% confluency using 0.025% trypsin-EDTA (NyClone) treatment. Peptide influence on the cell viability was estimated by using the MTS assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol (MTS, CellTiter96 AQ One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay, Promega) with minor modifications and as described elsewhere [20]. Human skin HaCaT (immortalized keratinocyte from AddexBio-T0020001) and kidney HEK293 cells were also cultivated for cytotoxicity evaluation of the peptides in a similar manner.

2.12. Peptide stability to proteases

After incubation with each protease at 37°C, peptide stability was evaluated by SDS-PAGE [24]. When degraded, no peptide band could be detected on a 5% stacking/18% resolving tricine gel after 2–4 h incubation at 37°C.

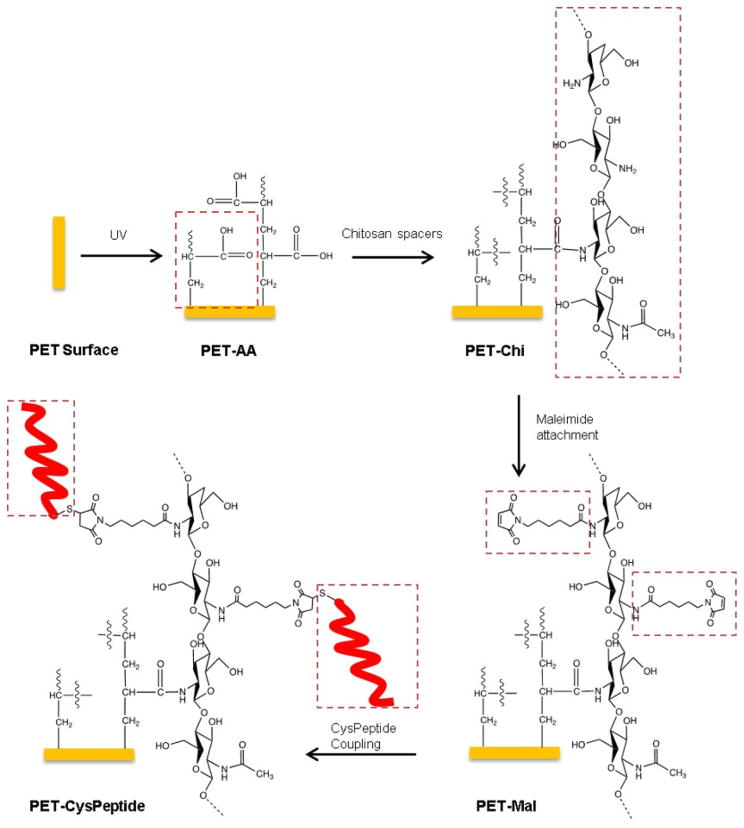

2.13. Site specific immobilization of CysTetraF2W-RR on the polymer surface

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) surfaces were purchased from Goodfellow Corporation (PA USA). The flat surfaces were cleaned twice with ethanol and dried prior to use for any chemical reaction. Surfaces were cut into 1.0 × 1.0 cm rectangular pieces and irradiated with UV (Dymax Light Curing Systems, CT, USA) at 400 W power. The sample was placed at a constant distance of 10 cm from the UV source while immersed in a solution containing 10% aqueous acrylic acid (monomer), 0.5 mM NaIO4 and benzyl alcohol (0.5% v/V). UV initiated radical formation and self-polymerization of acrylic acid (AA) were carried out under this condition for 30 min to allow for AA-brush formation. The AA-brush functionalized PET (PET-AA) surfaces were cleaned to remove unbound monomers by washing thoroughly in water for 24 h at 70°C with constant stirring. Following this, the carboxyl group on the brush was activated with 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) (0.1% w/V) for 3 h at 4°C [25]. The surfaces were then washed with a copious amount of distilled water and allowed to react with chitosan (0.5 wt% of 85% deacetylated form dissolved in 0.1 M acetic acid). Chitosan reacted with the activated carboxyl group via amine forming an amide bond. The product (PET-Chi) contained multiple free amine groups that were allowed to react with an aqueous solution of 6-maleimidohexanoic acid (2 mg/mL) in the presence of EDC (0.1% w/V) for 5 h at room temperature to produce surfaces with an exposed maleimide group (PET-Mal). Finally, an orientation specific covalent coupling of the CysTetraF2W-RR (1 mg/mL) peptide with the PET-Mal surface was accomplished in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.0 for 18 h at room temperature with stirring at 60 rpm. Unbound peptides were removed by thorough rinsing with deionized water.

2.14. Biophysical characterization of the peptide-coated surface

The peptide-functionalized PET surfaces were dried before characterization by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS).

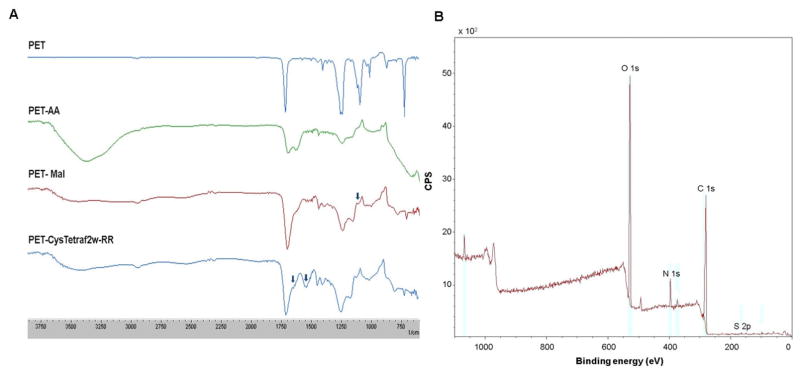

2.14.1. FT-IR spectroscopy

FT-IR spectroscopy was used to monitor the successful proceedings of the immobilization of CysTetraF2W-RR onto the PET surface. The presence of signature bands in the IR spectrum confirmed the preceding reactions. The spectrum was recorded from 600 to 4000 cm−1 by performing 20 scans on an IR Prestige-21 instrument (Shimadzu) using a Happ-Genzel apodization function.

2.14.2. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)

Samples were analyzed using a Surface Science Instrument SSX-100 with an operating pressure at ~2×10−9 Torr. Monochromatic Al K-alpha X rays (1486.6 eV) were used with a beam diameter of 1 mm. Photoelectrons were collected at a 55 degree emission angle. A hemispherical analyzer determined electron kinetic energy, using a pass energy of 150 V for wide/survey scans, and 50 V for high resolution scans. A flood gun was used for charge neutralization of non-conductive samples. Elements were identified from the survey spectra. High resolution spectra of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen and sulfur were recorded individually for elemental ratio comparison.

2.15. Measurement of the surface CysTetraF2W-RR concentration using sulfosuccinimidyl-4-o-(4,4-dimethoxytrityl) butyrate (Sulfo-SDTB)

The surface concentration of the covalently attached CysTetraF2W-RR was determined using a simple spectrophotometric assay. This method uses the high extinction coefficient of a complex ion formed by the reaction of the surface amino groups and Sulfo-SDTB [26]. In short, 1 mL of Sulfo-SDTB (3.0 mg/mL) solution was prepared in DMF and then made up to 50.0 mL with a 50 mM sodium bicarbonate solution (pH 8.5). 1.0 mL of this solution was added to the peptide coated PET samples and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The samples were then washed twice with 5.0 mL of distilled water to remove any unreacted reactant, and immersed in 2.0 mL of perchloric acid for another 30 min. Absorbance of the solution was measured at 498 nm to detect the DMTr cation. The number of amine groups on the surface of each sample was quantified using the Beer–Lambert law with an extinction coefficient of 70 000 M−1 cm−1 and finally the amount of immobilized CysTETRAF2W-RR was calculated by calibration with the predicted number of amines present in the peptide.

2.16. Antibacterial assays of the peptide-coated PET surface

Antibacterial activity of the PET-CysTetraF2W-RR samples was tested according to the previously published ISO 22196 protocol with minor modifications [27, 28]. In brief, the exponential phase S. aureus USA300 bacteria were adjusted to 105 CFU/mL in fresh TSB media. 20 μL of the cell suspension was added on the top of each PET surface placed in a well of a 24-well culture plate. Further, the plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 h, followed by addition of 280 μL of fresh TSB media. The media was mixed well to ensure all the adhered live cells to come off the surface and enter the media. 50 μL of the solution was then spread on the LB agar plates for CFU determination after 18 h incubation. The PET surfaces that went through the series of reactions without peptide coupling were used as a negative control.

2.17. Propidium iodide (PI) based membrane permeation assay of the CysTetraF2W-RR coated PET surface S. aureus

USA300 was inoculated and incubated overnight in the TSB medium. Next morning, they were regrown in fresh TSB to attain the mid-exponential phase. A bacterial count of 1× 108 CFU/mL was prepared in the same media. 200 μL of this culture was incubated with the PET surface with and without the peptide in a 24-well culture plate at 37°C, 150 rpm for 1 h. For detection of bacterial permeability, a 250 μM propidium iodide (PI) solution was also added prior to incubation. Surface coated PETs without peptide were considered as a negative control. Simultaneous determination of the bacterial growth by optical density (OD600) and PI fluorescence (excitation and emission wavelengths at 584 nm and 620 nm) caused by intercalation of the dye into the DNA of dead cells were monitored using FLUOstar Omega (BMG LABTECH Inc, NC, USA). Data were processed with the MARS software provided by the manufacturer.

2.18. Cellular cytotoxicity assessment for PET-CysTetraF2W-RR

HeLa CCL-2 cells from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) were maintained in DMEM high glucose media with 4 mM L-glutamine (NyClone) and 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin (pen/strep; p/s) (Life Technologies), and 10% (v/v) inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, NyClone), DMEM with 10% FBS, p/s. Cells were grown in 5% CO2 at 37°C and were detached from culturing dish at 100% confluency using 0.025% trypsin-EDTA (NyClone) treatment, seeded (18,000 cells/well) in 24-well plates (Corning Life Science) and grown overnight in 200 μL DMEM media until 70% confluency. Then the old media were replaced with 500 μL of fresh DMEM media and continued to cultivate for 1 h with the surfaces with or without peptides (1.0 × 1.0 cm). 200 μL of the liquid content of each well was taken out and mixed with 20 μL of MTS. The plate was further incubated for another 2 h at 37°C. To quantify the cytotoxicity, 100 μL of the solution was placed in a 96-well plate and the absorbance was measured on a ChroMate reader (Awareness Technology) at 492 nm. For comparison, we used the same amounts of soluble peptides and treated them in the same way as described above. Water and 0.2% SDS were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

2.19. Inhibition of biofilm formation by the peptide-coated surfaces

The inhibition of the biofilm formation by the PET-CysTetraF2W-RR surface was quantified using XTT assays. Briefly, S. aureus USA300 was adjusted to 105 CFU/mL. 1 mL of the culture was added to the wells of a 24-well culture plate containing surfaces that were uncoated, coated with and without the CysTetraF2W-RR peptide. The plates were then incubated at 37°C for 24 h to allow bacterial biofilm formation. Subsequently, media were removed and surfaces were washed three times with fresh autoclaved saline to remove any unattached cells. Fresh media containing 10% XTT solution with 1% PMS (N-Methylphenazonium methyl sulfate) were further incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Plates were read at 450 nm for calorimetric estimation of the biofilm masses. Plots were made for various coated surfaces relative to uncoated PET surfaces, which were assumed to have reached 100% biofilm formation.

2.20. Statistical analysis

For determining the minimal inhibitory concentrations, the experiments were conducted at least two times on different days and in duplicates wells. However, the average values were reported. For the rest of the experiments including biofilm inhibition assays, results were statistically analyzed based on paired student t-test with a two tailed distribution with a significance level of p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Design and antimicrobial activity of free peptides

Peptide design

Our design started from temporin-SHf, which is shortest in the helical family in the APD database [8]. This amphibian peptide is rich in phenylalanines (50%) with a partial helical structure bound to micelles [15]. Temporin-SHf is moderately active against E. coli ATCC 25922 and ML-35p strains (MIC 25–30 μM), but not E. coli ATCC 35218 (MIC >200 μM). It is also potent in killing Gram-positive B. megaterium (MIC 3 μM), although less effective against S. aureus ATCC 25923 (MIC 12.5 μM) [15]. In agreement with these data, we found a moderate activity for temporin-SHf against MRSA USA300 (MIC 25 μM). Temporin-SHf appeared to possess a minimal antimicrobial sequence since it lost its activity against a panel of bacteria when a phenylalanine residue was truncated from the N-terminus. To enhance peptide activity against MRSA, we converted this Phe-rich peptide into a Trp-rich sequence, leading to a novel peptide TetraF2W (Table 1). Our change was made based on the observation that tryptophans prefer the membrane interface [16–18, 29, 30]. Anti-MRSA assays revealed an MIC of 3.1–6.2 μM, which is 4–8 folds more potent than temporin-SHf (Table 2). TetraF2W was also bactericidal to B. subtilis, but showed no activity against E. coli and S. epidermidis at 50–100 μM.

Table 1.

Amino acid sequence and properties of the designed Trp-rich peptides1

| Peptide | Sequence | tRP (Min) | Purity (%) | M.Wt. | Net Charge | Pho% | Boman index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temporin-SHf | FFFLSRIF | 14.267 | 97.41 | 1076.3 | +2 | 75 | −0.42 |

| TetraF2W | WWWLSRIW | 14.539 | 98.33 | 1232.5 | +2 | 75 | −0.10 |

| TetraF2W-KR | WWWLKRIW | 13.657 | 95.62 | 1273.5 | +3 | 75 | 0.16 |

| TetraF2W-RK | WWWLRKIW | 13.682 | 96.56 | 1273.5 | +3 | 75 | 0.16 |

| TetraF2W-KK | WWWLKKIW | 13.586 | 96.03 | 1245.5 | +3 | 75 | −1.00 |

| TetraF2W-RR | WWWLRRIW | 13.821 | 96.88 | 1301.6 | +3 | 75 | 1.33 |

| TetraF2W-RK-d | wwwlrkiw | NE | 97.92 | 1273.5 | +3 | 75 | 0.16 |

Peptide purity and retention time (tRP) were measured on HPLC. Molecular weight (M.Wt.), net charge, hydrophobic ratio (pho%), and Boman index of each peptide were calculated using the Antimicrobial Peptide Database prediction interface (http://aps.unmc.edu/AP/prediction/prediction_main.php) [8]. NE, not evaluated.

Table 2.

Antibacterial activities of new Trp-rich peptides designed based on a natural template

| Peptide | MIC (μM) | MBC (μM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli K12 | S. epidermidis 1457 | B. subtilis 168 | S. aureus USA300 | S. aureus USA300 | |

| Temporin-SHf | >100 | >100 | >100 | 25 | NE1 |

| TetraF2W | >100 | >50 | 6.2 | 3.1–6.2 | 6.2 |

| TetraF2W-KR | 12.5–25 | 12.5 | 6.2 | 3.1 | 12.5 |

| TetraF2W-RK | 25 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 3.1 | 12.5 |

| TetraF2W-KK | 12.5–25 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 3.1–6.2 | >25 |

| TetraF2W-RR | 25 | 6.2–12.5 | 3.1–6.2 | 1.6–3.1 | 3.1 |

| TetraF2W-RK-d | 6.2 | 6.2 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 12.5 |

NE, not evaluated.

Next, we changed the polar S5 amino acid to basic K5 to increase peptide solubility in water. Interestingly, the new peptide TetraF2W-KR (Table 1) gained activity against both E. coli K12 and S. epidermidis, indicating the importance of the basic lysine in inhibiting these two bacteria strains. To find the best basic pair, we also made other peptides by replacing the RK pair with RK, KK, or RR (Table 1). These four peptides containing varying basic pairs showed similar antibacterial activity against E. coli, S. epidermidis, B. subtilis, and S. aureus USA300 in terms of MIC (Table 2). Importantly, these peptides were able to inhibit clinical strains of S. aureus (Mu50, Newman, and UAMS-1) at 3–6 μM (Table S1). Although the four dibasic TetraF2W peptides had similar MIC values against bacteria, they showed different minimal bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) against S. aureus USA300 (Table 2). While TetraF2W-RR was most potent (MBC 3.1 μM), TetraF2W-KK was weakest (MBC > 25 μM).

Effects of serum, salts, and pH on antibacterial activity

Since serum, salts, and pH can influence peptide activity, we also tested the effects of these factors on peptide activity against S. aureus USA300 [20]. The results are given in Table 3. Compared to the MIC values obtained in normal TSB (pH 7.4), the peptide activity was reduced by 4–8 folds in the presence of 5% human serum, probably due to association with serum proteins. However, these peptides were able to tolerate a change in pH. A drop of pH from 8 to 6.8 only caused a two-fold change in MIC for the three arginine-containing peptides (TetraF2W-RR, TetraF2W-RK and TetraF2W-KR). TetraF2W-KK, however, appeared to be more susceptible as its MIC reduced from 3.1 to 12.5 μM. This fact sheds light on the preferred Arg-Trp combinations in known Trp-rich peptides [29]. In addition, all TetraF2W peptides remained active (3.1–6.2 μM) even after the addition of 150 mM NaCl. Thus, these TetraF2W peptides, especially the RR variant, are resistant to salts and pH under the testing conditions.

Table 3.

Serum, salt, and pH on antimicrobial activities (in μM) of TetraF2W dibasic variants against S. aureus USA300

| Peptide | pH 8 | Normal medium (pH 7.4) | pH 6.8 | 150 mM NaCl | 5% Serum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TetraF2W-KK | 3.1 | 3.1–6.2 | 12.5 | 3.1–6.2 | 12.5 |

| TetraF2W-KR | 3.1 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 3.1 | 25 |

| TetraF2W-RK | 3.1 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 3.1 | 12.5 |

| TetraF2W-RR | 3.1 | 1.56–3.1 | 6.2 | 3.1 | 25 |

Antifungal activity of the peptides

We also compared the candidacidal ability of the four peptides (Table 4). In contrast to the bacterial cases, TetraF2W-RR was poorest against C. albicans, C. glabrata and C. tropicalis and TetraF2W-KK was most active. The RK and KR pair showed identical antifungal activities in all the cases.

Table 4.

Antifungal activities of Trp-rich TetraF2W peptides (MIC in μM)

| Peptide | Candida albicans | Candida glabrata | Candida tropicalis |

|---|---|---|---|

| TetraF2W-KK | 6.2 | 6.2–12.5 | 1.6 |

| TetraF2W-KR | 12.5 | 12.5 | 3.1–6.2 |

| TetraF2W-RK | 12.5 | 12.5 | 3.1–6.2 |

| TetraF2W-RR | 25 | >25 | 3.1 |

3.2. Mechanism of action of the short Trp-rich peptides

Killing kinetics

To further compare the potency of the new Trp-rich peptides, we conducted the traditional killing experiments based on colony counting. The order of S. aureus USA300 killing rate is TetraF2W-RR > TetraF2W-RK > TetraF2W-KR > TetraF2W-KK (Fig. 1A). Thus, TetraF2W-RR showed the fastest killing and all the bacteria (105 CFU) were killed in 90 min. The rapid killing implies that the peptide targeted bacterial membranes [31].

Fig. 1.

Staphylococcus aureus USA300 killing kinetics of the TetraF2W peptides based on (A) colony counting and (B) propidium iodide cell entrance assay. Untreated bacteria were used as a positive control (normal growth), while TSB media served as a negative control (no growth).

Real time fluorescence based kinetics of TetraF2W peptides

To confirm membrane targeting, we also followed the fluorescence change after peptide treatment of S. aureus USA300 in the presence of propidium iodide, which does not fluoresce until bacterial membranes are compromised. We have validated this approach by using a set of antibiotics with known mechanisms of action. While there is no increase in fluorescence when treated with vancomycin (cell wall targeting), a rapid increase in fluorescence occurs when treated with membrane-active daptomycin (not shown). The intensity of fluorescence was in the order of TetraF2W-RR > TetraF2W-KR ~ TetraF2W-RK > TetraF2W-KK (Fig. 1B). Thus, the peptide with the RR basic pair was most effective in damaging the membranes of S. aureus, whereas the peptide with the KK pair was least potent. The RK and KR peptides were found to have more or less similar potency in membrane permeation. Therefore, the results obtained here based on fluorescence spectroscopy are consistent with killing kinetics from colony counting obtained above, verifying that TetraF2W-RR is the most active peptide.

Live cell imaging of peptide treated bacterial cells by confocal microscopy

Since these four TetraF2W peptides (KK, KR, RK, and RR) are quite similar, we hypothesize that they work by a similar mechanism. To validate the membrane targeting of these peptides, we selected a different member TetraF2W-RK in this peptide series and incubated it with live S. aureus USA300 in the presence of a different dye FITC. Again, a time dependent increment of fluorescence was observed by confocal microscopy. FITC entered the cells rapidly and the majority of cells became visible in the window in 30 seconds (Supporting Fig. S1). The image at 115 s looked almost identical to those recorded at 295 s. This experiment also indicates that bacterial membranes were damaged by the peptide, opening the door to FITC [32].

Activity of the D and L forms of TetraF2W-RK

To provide additional insight, we also compared the MIC values of TetraF2W-RK synthesized using either entirely L-amino acids (normal one) or entirely D-amino acids. In the cases of three Gram-positive bacteria such as S. epidermidis, B. subtilis, and S. aureus, the D-form peptide displayed an MIC similar to the L-form (Table 2). Because the L and D-forms are mirror-imaged to each other, this result suggests that a chiral molecule is not involved in the peptide action, further confirming membrane targeting of this peptide against the panel of Gram-positive bacteria [14, 29]. However, we obtained rather different MIC values in the case of Gram-negative E. coli (25 μM for the L-form vs. 6.2 μM for the D form) (Table 2), implying that TetraF2W-RK might have inhibited the growth of E. coli by a different mechanism.

3.3. Anti-biofilm activity of TetraF2W-RR

In many settings, bacteria live together in the form of biofilms, where the community works together in a house covered with polysaccharides, DNA, and/or proteins. Such a community of bacteria poses challenge to medical treatment. Therefore, an anti-biofilm property of the designed peptide is desired. The TetraF2W-RR peptide exhibited excellent anti-biofilm activity against S. aureus USA300 (Fig. 2). TetraF2W-RR could reduce the adherence of the bacterial cells by 83% at 25 μM (Fig. 2A). Surface adherence is regarded as the first step for biofilm formation. Furthermore, it actively inhibited biofilm growth even at 6.25 μM. As shown in Fig. 2B, the peptide completely inhibited the biofilm formation at 25 μM. Finally, TetraF2W-RR disrupted ~77% of the preformed biofilms at 25 μM (Fig. 2C). To visualize the peptide effect on biofilms, confocal laser scanning microscopy was utilized to view the 24 h preformed biofilms after treatment with 25 μM of TetraF2W-RR (Fig. 2D). The cells in the biofilms were stained with a LIVE/DEAD Kit. In Fig. 2D, live cells stained with the SYTO9 dye became green (panel a), while the dead cells, after staining with a DNA-binding dye propidium iodide, turned red (panel b). Hence, TetraF2W-RR is capable of killing S. aureus USA300 in 24 h biofilms preformed on the 96-well tissue culture treated sterile polystyrene plate.

Fig. 2.

Anti-biofilm activity of TetraF2W-RR at 25 μM against S. aureus USA300. (A) Ability of the peptide to inhibit the attachment of the bacterial cells to the solid surfaces, (B) inhibition of biofilm formation, and (C) disruption of preformed biofilms quantified by XTT. Significant values are marked with a * with a P value of < 0.04 calculated based on paired student t-test with a two tailed distribution. (D) Confocal laser scanning microscopic images of S. aureus biofilms after LIVE/DEAD staining without (a) and with (b) peptide treatment. Provided are overlaid images of both the green and red channels.

3.4. Cytotoxicity of free peptides

To develop peptide therapeutics, cytotoxicity to mammalian cells must be minimized. To better evaluate the cytotoxicity of these peptides, we utilized a variety of eukaryotic cells. As shown in Table 5, TetraF2W peptides gave similar 50% lytic concentrations (LC50) [20]. We also compared the susceptibility of different types of animal blood cells to these new Trp-rich peptides and the LC50 values are also given in Table 5. Overall, we saw similar 50% hemolytic concentrations (HL50), although TetraF2W-RR appeared to be slightly more toxic than TetraF2W-KK in the cases of human and porcine blood cells. To further compare the results for the three animal blood cells, we also plotted cell lysis at 50 μM (Supporting Fig. S2). It seems that the porcine blood cells were most susceptible with 50–80% lysis. The chicken blood cells were slightly less lysed with 40–60% lysis, while the bovine blood cells were least lysed (10–20%). Thus, blood cells have different susceptibility to these peptides with porcine results more similar to humans.

Table 5.

Hemolytic abilities (LC50 μM) of new Trp-rich peptides TetraF2W using different animal blood cells and human cells

| Peptide | TetraF2W-KK | TetraF2W-KR | TetraF2W-RK | TetraF2W-RR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human RBCs | 40 | 30 | 30 | 20 |

| Porcine RBCs | 55 | 50 | 40 | 40 |

| Chicken RBCs | 50 | 35 | 35 | 55 |

| Human HEK293 | 50 | 55 | 60 | 70 |

| Human HaCaT | 50 | 60 | 60 | 70 |

| Human HeLa | 70 | 100 | >100 | 60 |

To better measure peptide cytotoxicity, we also utilized additional human cell lines: HeLa, HaCaT and HEK293. While HeLa cells are cancer cells, HaCaT and HEK293 are normal human skin and kidney cells, respectively. In the case of HeLa cells, we found a lytic order TetraF2W-RR ~ TetraF2W-KK > TetraF2W-KR ~ TetraF2W-RK (Fig. 3A). A different cytotoxicity order was observed for human HaCaT (Fig. 3B) and HEK293 (Table 5) cells: TetraF2W-KK > TetraF2W-RK ~ TetraF2W-KR > TetraF2W-RR. These results revealed small differences in peptide cytotoxicity depending on cell types. Note that the less toxic effects of the arginine variant on both HaCaT and HEK293 cells would make the TetraF2W-RR peptide more selective than the lysine analog.

Fig. 3.

Toxic effects of the TetraF2W peptides on HeLa CCL-2 (panels A, B, C and D) and HaCaT cells (panels E, F, G, and H). Significant values are marked with a * with a P value < 0.05 calculated based on paired student t-test with a two tailed distribution.

3.5. Stability of free peptides to select host and pathogen proteases

Because the L and D forms of peptides are known to have different stability to proteases [14, 33, 34], we also followed the digestion of TetraF2W-RK by a set of important proteases from both host and pathogens. This includes mammalian chymotrypsin, trypsin, S. aureus V8 protease, and fungal proteinase K. Interestingly, the L-form of TetraF2W-RK was not cut by trypsin and the S. aureus V8 protease at a peptide:protease molar ratio of 40:1, although it was completely degraded by chymotrypsin and fungal proteinase K in 24 h. In the case of the D-form, TetraF2W-RK remained stable to all the proteases tested here (Fig. 4). Thus, TetraF2W-RK has inherent stability to trypsin and the S. aureus V8 protease, and became even more stable when made in D-amino acids.

Fig. 4.

Peptide stability comparison of the L- and D-forms of TetraF2W-RK after 24 h incubation with chymotrypsin, trypsin, Staphylococcus aureus V8 protease, or proteinase K, which are represented with C, T, V8, and K in the figure, respectively.

3.6. Covalent immobilization of CysTetraF2W-RR on the PET surface

Fig. 5 depicts a schematic diagram for the immobilization of CysTetraF2W-RR onto the PET surface. A cysteine residue was appended at the N-terminus of the peptide (i.e., CysTetraF2W-RR) to allow for coupling to the surface via the maleimide-cysteine reaction. To increase peptide coating density, “brushes” were generated on the PET surface through irradiation with high energy UV. The transfer of UV-generated radicals led to the formation of acrylic acid polymers (brushes) with protruding carboxyl groups, which were further activated by EDC. These activated carboxylic functional groups were then coupled to amine groups of chitosan via forming an amide bond. Since chitosan is a long chain polymer, we used it as a spacer to increase the chance for the coupled peptide to remain antimicrobial. Next, 6-maleimidohexanoic acid was coupled with an amide group of chitosan. This coupling generated free maleimide groups on the surface for site-directed peptide coupling via the sulfhydryl group of the N-terminal cysteine of TetraF2W-RR at pH 7. In the following, we provide physical, chemical, and biological evidence for the success coating of the peptide.

Fig. 5.

Schematic diagram that depicts the reaction for covalent immobilization of CysTetraF2W-RR onto the PET surface. Newly appended groups in each step are boxed in dotted red lines. See the text for further details.

3.7. Characterization of the PET-CysTetraF2W-RR surface

FT-IR and XPS analysis of the immobilized CysTetraF2W-RR

Each chemical reaction toward peptide coupling was monitored by FT-IR based signature peaks generated (Fig. 6A). The grafting of acrylic acid brush lead to a broad band at 1718 cm−1 characteristic of stretching absorption band of the carbonyl group C=O, and weak vibration bands at 1456 cm−1 corresponding to the -CH2- group. The coupling between the in-plane OH bending and C-O stretching vibration of neighboring carboxyl group generated the bands at 1248 cm−1 and 1174 cm−1, respectively [35]. The chitosan and maleimide coupling to the surface generated the 1080 cm−1 band typical for glucopyranose form chitosan [36] and the increment of the 1718 cm−1 band for additional C=O groups from the acetylated chitosan and maleimide units. Subsequent peptide immobilization led to the increment of the amide I stretching band at 1650 cm−1 which was hidden in the shoulder of 1718 cm−1 and is now more prominent. Further, the band at 1560 cm−1 corresponds to the amide II from the immobilized CysTetraF2W-RR. These spectral signatures convey a strong evidence for the successful proceedings of the reactions to the final product.

Fig. 6.

Biophysical characterization of the peptide-coated PET surface. (A) FT-IR spectra for the products at major reaction steps during the TetraF2W immobilization to the PET surface. The arrow (black) represent the characteristic peaks of glucopyranose at 1080 cm−1, the amide I and amide II at 1650 and 1560 cm−1 respectively. (B) Wide spectrum XPS spectra of the final product showing typical spectra of N 1s and S 2p. Elemental composition is provided in the Supporting Table S2.

An elemental composition analysis of the reaction product by XPS revealed wide range spectra for the N 1s, C 1s, O 1s and S 2p electrons. Since sulfur is only present in the peptide, the S 2p peak appearing around 164 eV (Fig. 6B) would support a successful grafting of the CysTetraF2W-RR peptide onto the PET surface. Note that the peak intensity for sulfur is low (supporting Fig. S3A), it is not conclusive (cf. supporting Fig. S3 B and C). The atomic content of each element is given in the supporting Table S2. However, the success of peptide coupling to the PET surface is also supported by other experiments below.

Chemical quantification of the immobilized CysTetraF2W-RR

The immobilized peptide was quantified by using a simple calorimetric method that estimates the amount of free amino group on the surface. The Sulfo-SDTB reacts specifically with the free surface amino group and produces a complex, which on further acid treatments breaks to form a 4,4′-dimethoxytrityl cation (DMTr ion). This ion has a strong absorbance at 498 nm with a high extinction coefficient of 70,000 M−1cm−1 [26]. Based on the amounts of free amine present in the peptide, the amount of peptide tethered was back calculated. Since chitosan also have free amino groups, its contribution (6.92 ± 1.10 × 10−10 mol cm−2) had to be deducted from the total amount of amino groups. The coating density of CysTetraF2W-RR was found to be 2.81 ± 0.68 × 10−10 mol cm−2.

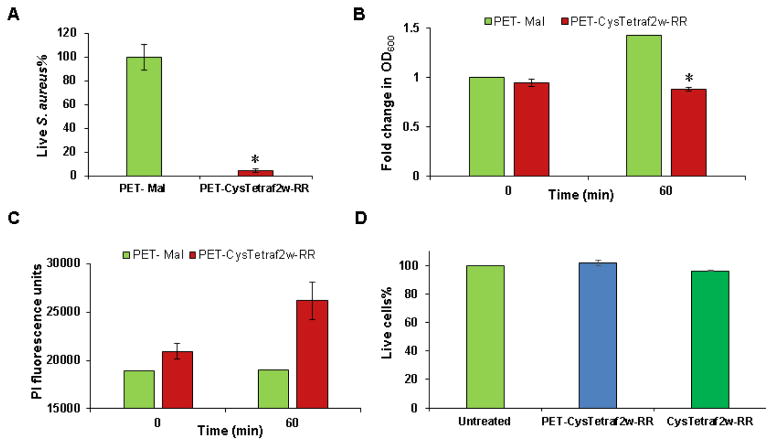

Antimicrobial and cytotoxicity activity of the CysTetraF2W-RR coated PET surface

To demonstrate surface activity, we conducted both traditional killing experiments based on a modified ISO 22196 protocol and fluorescence-based monitoring of dead bacteria. The PET-CysTetraF2W-RR surface was found to have excellent biocidal properties against S. aureus USA300. In the traditional colony counting assay, it eradicated about 95% of live bacteria compared to the control surface without peptide immobilization (Fig. 7A). In another assay where the surface was incubated with more bacteria, they did not allow any further growth and reduced the overall bacterial burden, too. While the bacterial growth (OD600) showed a 1.5-fold increment for the surface devoid of peptide, the CysTetraF2W-RR coated PET surface decreased the growth by 40% (Fig. 7B). This observation was also validated by an increase in the PI fluorescence (Fig. 7C), which corresponds to a drop in OD600 measured in the same experiment. The increase in the PI fluorescence here is reminiscent of our previous observation with the same peptide in the free form (Fig. 1B, red curve). We conclude that the immobilized peptide also killed S. aureus via membrane permeation.

Fig. 7.

Antimicrobial and cell cytotoxicity of the PET surface coated with CysTetraF2W-RR. (A) S. aureus USA300 killing efficacy of the peptide-coated surfaces as determined by the standard colony counting method. (B) Kinetic killing of S. aureus USA300 as a function of optical density with respect to time. (C) Time-dependent increase in the number of dead cells based on the propidium iodide fluorescence. (D) Cytotoxicity of PET-CysTetraF2W-RR to Hela CCL-2 cell lines (blue). An equal amount of soluble peptide was used for comparison (dark green). Dead cells are represented by red bars. Significant values are marked with a * with a P value < 0.05 calculated based on paired student t-test with a two tailed distribution.

We also compared the cytotoxicity of the peptide immobilized surface. When 1 cm2 of the TetraF2W-RR peptide coated surface was incubated with HeLa CCL-2 cells for an hour, we did not observe any change in the percentage of live cells (Fig. 7D blue), confirming that the surface was not toxic to these cells. Under the same conditions, an equivalent amount of free peptide CysTetraF2W-RR was also nontoxic (Fig. 7D dark green).

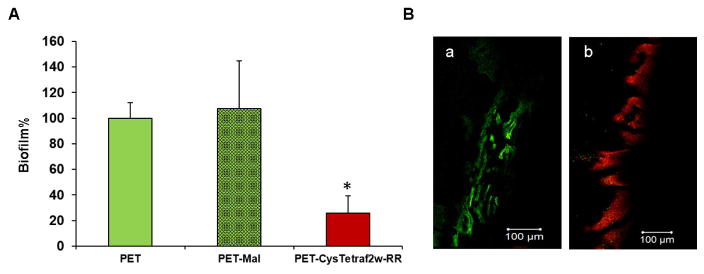

Anti-biofilm activity of the CysTetraF2W-RR coated PET surface

Fig. 8 shows the outcome of anti-biofilm assays using the peptide coated surface. The PET-CysTetraF2W-RR surface reduced the formation of biofilm of S. aureus USA300 by 70% after 24 h incubation. On contrary, there was no significant change in the biofilm mass formed on the uncoated PET surface, or the surface that went through the same chemistry without the last step of peptide coupling. Hence, the reduction in biofilms could be attributed to the effect of the covalently attached peptide, rather than other chemicals, including chitosan, that facilitate the coupling of the peptide to the PET surface.

Fig. 8.

Anti-biofilm activity of the CysTetraF2W-RR coated PET surface. (A) Biofilm formation was allowed for 24 h followed by quantitative estimation using the XTT assay. The PET surfaces without coating were regarded as 100% biofilm growth whereas coated surfaces without the last step of peptide coupling were compared with the CysTetraF2W-RR coated PET surface to see the distinct effects of peptide immobilization. Significant values are marked with a * with a P value < 0.01 calculated based on paired student t-test with a two tailed distribution. (B) Confocal laser scanning microscopic images of 24 h S. aureus biofilms after LIVE/DEAD staining on (a) PET-Mal control and (b) PET-CysTetraF2W-RR coated surface. The images are the overlaid ones of both the green and red channels. The presence of a large number of dead cells due to propidium iodide red staining on the peptide immobilized surface provides clear evidence for its antibiofilm nature.

4. Discussion

There is a great interest in developing AMPs into therapeutic molecules [37, 38]. Short peptides occupy an important niche because they may be made cost effectively [39, 40]. The construction of the APD database facilitates peptide discovery [8, 41]. With the aid of the database, we succeeded in generating a family of short Trp-rich peptides based on a Phe-rich temporin-SHf template [15]. The TetraF2W peptides contain only eight residues with 50% Trp, higher than those in known Trp-rich peptides [8, 29]. In particular, the anti-Staphylococcal activity of the double arginine variant TetraF2W-RR increased by 8 fold, emerging as the most potent peptide for killing MRSA (MBC 3.1 μM in Table 2). To elucidate the molecular basis for this, we found that the MBCs of the four TetraF2W variants corresponded exactly to their HPLC retention times (Supporting Fig. S4A). It suggests that the double RR variant is slightly more hydrophobic than the lysine-containing peptides (Table 1), explaining its more efficient MRSA-killing ability (Table 2). Likewise, the Boman index also correlates with MBC of these peptides (Supporting Fig. S4B). Because Boman index was derived from the partition coefficient of the peptide between water and cyclohexane [37, 42], it is related to peptide hydrophobicity as well. Interestingly, in a combined classification of 20 amino acids based on 144 hydrophobic scales, arginine appears in the hydrophobic amino acid group, whereas lysine is located in the hydrophilic group [43]. The more efficient killing of the arginine variant is also attributed to the bifurcated hydrogen bonding ability of arginines [44–46]. It is also likely that the cation of the arginine side chain interacts with the π electron of aromatic amino acids [29]. Such unique properties may explain why arginines are preferred in short Trp-rich peptides obtained from combinatorial libraries [30]. Of particular interest is our finding that the arginine variant tends to be more potent against bacteria, but less cytotoxic to select human cells than the lysine-containing analogs. Such a Trp-Arg combination would lead to a more selective defense molecule, revealing a fundamental design principle for Trp-rich AMPs.

The growth of biofilms on medical devices constitutes a difficult-to-treat problem in hospitals, especially when different microbes are involved. To prevent biofilm formation, we also succeeded in coating the most potent peptide TetraF2W-RR to the PET surface, which is widely used in medical devices. A surface with anti-biofilm ability may get rid of the need to replace infected medical implants. We used chitosan as a linker here, which was insufficient by itself to exert the anti-biofilm property demonstrated in Fig. 8. We also utilized the brush-based chemistry, which is advantageous because it can increase coating density of anti-biofilm peptides [47]. Godoy-Gallardo et al. [48] found that coating more the hLf1-11 peptide to titanium via surface-initiated atom transfer radial polymerization better reduced bacterial attachment than the silanization method. Coating of a 13mer GL13K peptide also made the titanium surface antibiofilm [49]. Likewise, immobilization of a 15mer lasioglossin LL-III to silicone catheters conferred antibiofilm ability to the device [50]. Recently, Xavier et al. showed that synthetic lactams could also inhibit the growth of Streptococcus mutans on titanium [51]. Our design of shorter AMPs (8mers) for coating has a practical consequence because such peptides can be made more cost effectively than long peptides. It is also advantageous that the designed peptide disrupted S. aureus USA300 membranes both in the free and immobilized forms. Such a mechanism of action renders it difficult for this superbug to develop resistance to the newly designed compound [31, 38, 52]. Surface immobilization of antimicrobial peptides offers other advantages such as decrease in potential cytotoxicity and increase in lifetime of the peptide [48, 49]. Significantly, such coated surfaces have the potential to relief the pain and cost of patients and the burden of doctors in replacing infected medical devices.

Conclusions

In summary, this study documents a group of new Trp-rich antibacterial peptides designed based on the shortest helix template in the antimicrobial peptide database [8]. Compared to the temporin-SHf template, the designer peptide gains 8-fold potency against MRSA USA300. The potency of the double arginine peptide TetraF2W-RR is attributed to its increased hydrophobicity than other dibasic analogs containing KK, KR, or RK pairs. Importantly, at the Staphylococcal killing concentration (3 μM), none of these short peptides would be toxic to the host. In addition, these short Trp-rich peptides also possess inherent stability to select proteases and are easy to synthesize chemically, making them attractive templates for developing new antimicrobials to combat MRSA. Through this study, we also elucidate an important design principle of Trp-rich AMPs that a combination of Trp and Arg appears to generate a needed advantage: potency against invading microbes, but low cytotoxicity to the host.

As an alternative strategy, we demonstrate that covalent immobilization of TetraF2W-RR onto the polymer surface prevents bacterial biofilm formation. Importantly, we show that the peptide after immobilization kills S. aureus USA300 in the same mechanism as the free TetraF2W-RR by disrupting bacterial membranes. Taken together, our study lays a foundation for the two potential applications of these short peptides: (1) antimicrobials to treat patients and (2) biofilm-resistant agents coated on the surfaces of implanted medical devices.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

It is stunning that the total deaths due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection are comparable to AIDS/HIV-1, making it urgent to explore new possibilities. This study deals with this problem by two strategies. First, we have designed a family of novel antimicrobial peptides with merely eight amino acids, making it cost effective for chemical synthesis. These peptides are potent against MRSA USA300. Our study uncovers that the high potency of the tryptophan-rich short peptide is coupled with arginines, whereas these Trp- and Arg-rich peptides are less toxic to select human cells than the lysine-containing analogs. Such a combination generates a more selective peptide. As a second strategy, we also demonstrate successful covalent immobilization of this short peptide to the polyethylene terephthalate (PET) surface by first using the chitosan linker, which is easy to obtain. Because biofilms on medical devices are difficult to remove by traditional antibiotics, we also show that the peptide coated surface can prevent biofilm formation. Although rarely demonstrated, we provide evidence that both the free and immobilized peptides target bacterial membranes, rendering it difficult for bacteria to develop resistance. Collectively, the significance of our study is the design of novel antimicrobial peptides provides a useful template for developing novel antimicrobials against MRSA. In addition, orientation- specific immobilization of the same short peptide can prevent biofilm formation on the PET surface, which is widely used in making prosthetic heart valves cuffs and other bio devices.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by the grants from the State of Nebraska (Nebraska Research Initiative) and NIAID/NIH (R01AI105147 and R03 AI128230) to GW. These funding agencies are not involved in the experimental design, conduction, data interpretation, or manuscript preparation for publication. We thank Dr. Alekha K. Dash and his colleagues at Creighton University for assistance with the FT-IR measurements, Janice Taylor and James R. Talaska for confocal microscopy (UNMC), and the Cornell Center for Materials Research Shared Facilities at Cornell University (supported by the NSF MRSEC program DMR-1120296) for XPS analysis.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Except for a patent application that covers the novel peptides reported here, there is nothing to declare regarding conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.http://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/flemingpenicillin.html

- 2.Bancroft EA. Antimicrobial resistance: it’s not just for hospitals. JAMA. 2007;298:1803–1804. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy AD, Otto M, Braughton KR, Whitney AR, Chen LL, Mathema B, et al. Epidemic community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: recent clonal expansion and diversification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1327–1332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710217105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishna S, Miller LS. Innate and adaptive immune responses against Staphylococcus aureus skin infections. Semin Immunopathol. 2012;34:261–280. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0292-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, Petit S, Gershman K, Ray S, et al. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:1763–1771. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klimek JJ, Marsik FJ, Bartlett RC, Weir B, Shea P, Quintiliani R. Clinical, epidemiologic and bacteriologic observations of an outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at a large community hospital. Am J Med. 1976;61:340–345. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(76)90370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang G. Database-guided discovery of potent peptides to combat HIV-1 or Superbugs. Pharmaceuticals. 2013;6:728–758. doi: 10.3390/ph6060728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang G, Li X, Wang Z. APD3: the antimicrobial peptide database as a tool for research and education. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D1087–1093. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang G. Human Antimicrobial Peptides and Proteins. Pharmaceuticals. 2014;7:545–594. doi: 10.3390/ph7050545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang G, Li Y, Li X. Correlation of three-dimensional structures with the antibacterial activity of a group of peptides designed based on a nontoxic bacterial membrane anchor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5803–5811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410116200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Li Y, Han H, Miller DW, Wang G. Solution structures of human LL-37 fragments and NMR-based identification of a minimal membrane-targeting antimicrobial and anticancer region. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:5776–5785. doi: 10.1021/ja0584875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang G. Structures of human host defense cathelicidin LL-37 and its smallest antimicrobial peptide KR-12 in lipid micelles. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32637–32643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805533200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menousek J, Mishra B, Hanke ML, Heim CE, Kielian T, Wang G. Database screening and in vivo efficacy of antimicrobial peptides against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;39:402–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mishra B, Wang G. Ab initio design of potent anti-MRSA peptides based on database filtering technology. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:12426–12429. doi: 10.1021/ja305644e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbassi F, Lequin O, Piesse C, Goasdoue N, Foulon T, Nicolas P, et al. Temporin-SHf, a new type of phe-rich and hydrophobic ultrashort antimicrobial peptide. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16880–16892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.097204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yau WM, Wimley WC, Gawrisch K, White SH. The preference of tryptophan for membrane interfaces. Biochemistry. 1998;37:14713–14718. doi: 10.1021/bi980809c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang G, Pierens GK, Treleaven WD, Sparrow JT, Cushley RJ. Conformations of human apolipoprotein E(263–286) and E(267–289) in aqueous solutions of sodium dodecyl sulfate by CD and 1H NMR. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10358–10366. doi: 10.1021/bi960934t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khandelia H, Kaznessis YN. Cation-pi interactions stabilize the structure of the antimicrobial peptide indolicidin near membranes: molecular dynamics simulations. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:242–250. doi: 10.1021/jp064776j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pace CN, Vajdos F, Fee L, Grimsley G, Gray T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2411–2423. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mishra B, Lushnikova T, Wang G. Small lipopeptides possess anti-biofilm capability comparable to daptomycin and vancomycin. RSC Advances. 2015;5:59758–59769. doi: 10.1039/C5RA07896B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang G, Elliott M, Cogen AL, Ezell EL, Gallo RL, Hancock RE. Structure, dynamics, and antimicrobial and immune modulatory activities of human LL-23 and its single-residue variants mutated on the basis of homologous primate cathelicidins. Biochemistry. 2012;51:653–664. doi: 10.1021/bi2016266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang G, Epand RF, Mishra B, Lushnikova T, Thomas VC, Bayles KW, et al. Decoding the functional roles of cationic side chains of the major antimicrobial region of human cathelicidin LL-37. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:845–856. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05637-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dean SN, Bishop BM, van Hoek ML. Natural and synthetic cathelicidin peptides with anti-microbial and anti-biofilm activity against Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang G, Hanke ML, Mishra B, Lushnikova T, Heim CE, Chittezham Thomas V, Bayles KW, Kielian T. Transformation of human cathelicidin LL-37 into selective, stable, and potent antimicrobial compounds. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:1997–2002. doi: 10.1021/cb500475y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huh MW, Kang I, Lee DH, Kim WS, Lee DH, Park LS, Min KE, et al. Surface characterization and antibacterial activity of chitosan-grafted poly(ethylene terephthalate) prepared by plasma glow discharge. J Appl Polym Sci. 2001;81:2769–2778. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaur RK, Gupta KC. A spectrophotometric method for the estimation of amino groups on polymer supports. Anal Biochem. 1989;180:253–258. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90426-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mishra B, Basu A, Saravanan R, Xiang L, Yang LK, Leong SSJ. Lasioglossin-III: Antimicrobial characterization and feasibility study for immobilization applications. RSC Adv. 2013;3:9534–9543. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kowalczuk D, Ginalska G, Golus J. Characterization of the developed antimicrobial urological catheters. Int J Pharm. 2010;402:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan DI, Prenner EJ, Vogel HJ. Tryptophan- and arginine-rich antimicrobial peptides: structures and mechanisms of action. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:1184–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blondelle SE, Takahashi E, Dinh KT, Houghten RA. The antimicrobial activity of hexapeptides derived from synthetic combinatorial libraries. J Appl Bacteriol. 1995;78:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1995.tb01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature. 2002;415:389–395. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oren Z, Shai Y. Mode of action of linear amphipathic alpha-helical antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers. 1998;47:451–463. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1998)47:6<451::AID-BIP4>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bessalle R, Kapitkovsky A, Gorea A, Shalit I, Fridkin M. All-D-magainin: chirality, antimicrobial activity and proteolytic resistance. FEBS Lett. 1990;274:151–155. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81351-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merrifield EL, Mitchell SA, Ubach J, Boman HG, Andreu D, Merrifield RB. D-enantiomers of 15-residue cecropin A-melittin hybrids. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1995;46:214–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1995.tb00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moharram MA, Rabie SM, EL-Gendy HM. Infrared Spectra of -Irradiated Poly(acrylic acid)–Polyacrylamide Complex. J Applied Polymer Sci. 2002;85:1619–1623. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Costa FM, Maia SR, Gomes PA, Martins MC. Dhvar5 antimicrobial peptide (AMP) chemoselective covalent immobilization results on higher antiadherence effect than simple physical adsorption. Biomaterials. 2015;52:531–538. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boman HG. Antibacterial peptides: basic facts and emerging concepts. J Intern Med. 2003;254:197–215. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hancock RE, Sahl HG. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1551–1557. doi: 10.1038/nbt1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mishra B, Srivastava VK, Chaudhry R, Somvanshi RK, Singh AK, Gill K, et al. SD-8, a novel therapeutic agent active against multidrug-resistant Gram positive cocci. Amino Acids. 2010;39:1493–1505. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0618-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mangoni ML, Shai Y. Short native antimicrobial peptides and engineered ultrashort lipopeptides: similarities and differences in cell specificities and modes of action. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:2267–2280. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0718-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang G, Watson KM, Peterkofsky A, Buckheit RW., Jr Identification of novel human immunodeficiency virus type 1-inhibitory peptides based on the antimicrobial peptide database. Antimicrob, Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1343–1346. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01448-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Radzicka A, Wolfenden R. Comparing the polarities of the amino acids: side-chain distribution coefficients between the vapor phase, cyclohexane, 1-octanol, and neutral aqueous solution. Biochemistry. 1998;27:1664–1670. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trinquier G, Sanejouand YH. Which effective property of amino acids is best preserved by the genetic code? Protein Eng. 1998;11:153–169. doi: 10.1093/protein/11.3.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hart KW, Clarke AR, Wigley DB, Chia WN, Barstow DA, Atkinson T, et al. The importance of arginine 171 in substrate binding by Bacillus stearothermophilus lactate dehydrogenase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;146:346–353. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90731-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen LT, de Boer L, Zaat SA, Vogel HJ. Investigating the cationic side chains of the antimicrobial peptide tritrpticin: hydrogen bonding properties govern its membrane-disruptive activities. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808:2297–2303. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmidt NW, Mishra A, Lai GH, Davis M, Sanders LK, Tran D, et al. Criterion for amino acid composition of defensins and antimicrobial peptides based on geometry of membrane destabilization. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:6720–6727. doi: 10.1021/ja200079a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiang H, Xu FJ. Biomolecule-functionalized polymer brushes. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:3394–3426. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35453e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Godoy-Gallardo M, Mas-Moruno C, Yu K, Manero JM, Gil FJ, Kizhakkedathu JN, Rodriguez D. Antibacterial Properties of hLf1–11 Peptide onto Titanium Surfaces: A Comparison Study Between Silanization and Surface Initiated Polymerization. Biomacromolecules. 2015;16:483–496. doi: 10.1021/bm501528x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen X, Hirt H, Gorr SU, Aparicio C. Antimicrobial GL13K peptide coatings killed and ruptured the wall of Streptococcusgordonii a nd prevented formation and growth of biofilms. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mishra B, Basu A, Chua RRY, Saravanan R, Tambyah PA, Ho B, Chang MW, Leong SSJ. Site specific immobilization of a potent antimicrobial peptide onto silicone catheters: evaluation against urinary tract infection pathogens. J Mater Chem B. 2014;2:1706–1716. doi: 10.1039/c3tb21300e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xavier JG, Geremias TC, Montero JF, Vahey BR, Benfatti CA, Souza JC, Magini RS, Pimenta AL. Lactam inhibiting Streptococcus mutans growth on titanium. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2016;68:837–841. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang G, Mishra B, Lau K, Lushnikova T, Golla R, Wang X. Antimicrobial peptides in 2014. Pharmaceuticals. 2015;8:123–150. doi: 10.3390/ph8010123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.