Abstract

Access to supermarkets is lacking in many rural areas. Small food stores are often available, but typically lack healthy food items such as fresh produce. We assessed small food store retailer willingness to implement 12 healthy store strategies to increase the availability, display, and promotion of healthy foods and decrease the availability, display, and promotion of tobacco products. Interviews were conducted with 55 small food store retailers in three rural North Carolina counties concurrently with store observations assessing current practices related to the strategies. All stores sold low-calorie beverages, sugar-sweetened beverages, candy and cigarettes. Nearly all sold smokeless tobacco and cigars/cigarillos, and 72% sold e-cigarettes. Fresh fruits were sold at 30.2% of stores; only 9.4% sold fresh vegetables. Retailers reported being most willing to stock skim/low-fat milk, display healthy snacks near the register, and stock whole wheat bread. About 50% were willing to stock at least three fresh fruits and three fresh vegetables, however only 2% of stores currently stocked these foods. Nearly all retailers expressed unwillingness to reduce the availability of tobacco products or marketing. Our results show promise for working with retailers in rural settings to increase healthy food availability in small food stores. However, restrictions on retail tobacco sales and marketing may be more feasible through local tobacco control ordinances, or could be included with healthy foods ordinances that require stores to stock a minimum amount of healthy foods.

Introduction

Obesity rates are higher, and the prevalence of current smoking is greater among adults living in rural compared with urban counties, particularly in the Southern United States (U.S.).1, 2 Limited neighborhood food access and high tobacco retailer density/point-of-sale tobacco marketing have been investigated as underlying factors contributing to disparities in obesity3 and smoking, respectively.4 Residents of rural areas often do not have easy access to large supermarkets5, 6 while convenience stores are more readily available.7 Healthy foods and beverages may not be common in convenience stores,6 while energy dense foods, sugar-sweetened beverages8 and tobacco products9 are typically abundant. Given that rural convenience stores may play an important role in providing staple foods between supermarket trips,10 understanding the determinants of stocking healthier products could help inform programs or interventions designed to increase healthy food access in small food stores.

Small food stores are therefore a promising intervention venue to increase healthy food access in areas underserved by large supermarkets.11 However, most ‘healthy stores’ efforts in the U.S. have been conducted in urban areas12, 13 while fewer have targeted small food stores in rural areas.14, 15 A common theme across small food store research is that owners/managers may not stock healthier foods and beverages because they do not perceive customer demand for healthy food, 16–18 however, studies have found customers would purchase fresh fruits and vegetables at the small food stores if they were available.19

Given that there may be a disconnect between retailer perceptions of customer demand and customer purchasing behavior, understanding retailers’ perspectives on stocking and promoting more healthy products, and fewer unhealthy products, could help inform future interventions and programs. This study fills a gap in the literature by assessing retailers’ willingness to implement strategies to increase the availability and promotion of healthy foods and limit tobacco products and marketing in small food stores in a rural area and comparing that expressed willingness with their current practices.

Methods

Study setting and participant recruitment

We recruited a convenience sample of small food store retailers in Lenoir, Wayne and Wilson Counties in Eastern North Carolina (NC). All three counties are rural, have a lower than state average median household income, greater than 20% of residents living in poverty, and multiple areas within the county designated as food deserts, or low income tracts with low access to large supermarkets.20, 21 We obtained a list of stores and addresses using ReferenceUSA, a commercial database. Stores were eligible if they were a non-chain grocery, convenience store or convenience store with gas station, were independently owned or managed, and had three or fewer primary cash registers.

Five trained research assistants (RAs) received a list of store names and addresses and visited the stores in person to assess store eligibility. After store eligibility was ascertained, the RA attempted to recruit retailers. RAs visited stores primarily during non-peak hours (approximately between 9AM and 6PM) to maximize the chances of retailers being available. If the retailer was unavailable, RAs reattempted stores up to three times and/or returned at times specified by the retailer to complete the screening. Participant eligibility criteria included the owner/manager of a small food store in the study counties who was; 1) in charge of stocking food and tobacco products; 2) able to complete the interview in English; and 3) age 18 or older. Participants received a $25 gift card for their participation. Informed consent was verbally obtained, and the procedures were approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board (IRB Study # 14-0645).

Of the 108 stores visited, 91 stores were located and screened for eligibility. Of these, 18 were excluded because they had more than three registers, and one retailer was ineligible due to language. This left 72 eligible retailers; 17 declined participation and 55 completed interviews (76% response rate). Eligible participants were asked to conduct the interview in a quiet part of the store. The data collection instrument included a retailer questionnaire and a store observation form. Store observations were conducted after the interview and were successfully completed in all but one of the 55 stores (one store missing because of RA safety concerns). RAs used iPads© with 3G internet access to record responses to the questionnaire and complete store observation forms via the online survey interface Qualtrics. If internet access was unavailable, RAs used a paper version of the survey instrument and later entered survey responses online. Data collection took place in July 2014.

Measures

Retailer and Organizational Characteristics

Retailer age, gender, and education level were measured. All stores were independently managed and small in size, therefore store type was further defined by the presence of a gas station. Retailers also reported whether the store accepted WIC and SNAP benefits.

Retailer willingness to implement a healthy store strategy

“Willingness” was assessed for seven healthy food strategies and four strategies related to tobacco products. The strategies were chosen based on previous interventions and programs that work with retailers to increase the availability of healthier foods and beverages in small food stores. The healthy food strategies were: 1) Stock at least 3 choices of fresh fruits and 3 choices of fresh vegetables, 2) Stock prepared fresh fruits or vegetables, like pre-cut apple slices or carrot sticks, 3) Stock any frozen fruits or vegetables, 4) Stock skim, 1% or 2% milk, 5) Stock whole wheat bread, like Nature’s Promise 100% Wheat Bread, 6) Display healthy snacks such as fruit at or next to the checkout counter, 7) Move soda, chips or candy displays away from the register. The tobacco product strategies were: 1) Remove ads/signs for tobacco products outside the store, 2) Remove ads/signs for tobacco products inside the store, 3) Move tobacco product displays away from the register, 4) Not sell any type of tobacco product.

Willingness was assessed under the following situation:

“There are local programs in our state that help small stores like yours become a “healthy store” that sells healthier foods. Stores receive advice on how to sell healthier foods, and some help with marketing and community outreach, and in return, the store owner agrees to make some changes. If you were to receive some assistance through a program like this, tell me how willing you would be to make the following changes. If you already do these things, tell me how willing you are to keep on doing them.”

Willingness to implement each strategy was measured on a 5 point scale from not at all willing to very willing.

Store observation

The store observation assessed the stocking, promotion and display of healthy foods and beverages and tobacco products and was used to assess current practices as they relate to the healthy store strategies proposed. Healthy foods/beverages included fresh (whole and pre-cut) and frozen fruits and vegetables, whole wheat bread, low-calorie beverages (bottled water, diet soda), and low-fat/fat free milk. Tobacco products included cigarettes, cigars/cigarillos, smokeless tobacco and e-cigarettes. For a descriptive comparison, we also examined the presence of less healthy food/beverage products: candy, white bread, sugar-sweetened beverages (e.g. soda, sweetened juices and teas), and whole milk. Data collectors observed both the store exterior and interior. For each food/beverage, the interior observation examined product availability (adapted from the NEMS-S instrument22), product placement (i.e. displayed on aisle endcaps, near a primary checkout register), the presence of price promotions (e.g. buy one get one free), and ads. If an ad contained both a healthy and unhealthy product (e.g. soda and diet soda), it was counted once in each category. For each tobacco product, the interior observation examined product availability, product placement (i.e. displayed near a primary checkout register), the presence of price promotions, and ads. The exterior observation examined the presence of price promotions and ads on the building exterior and property for both food/beverages and tobacco products.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated using Stata 12 to summarize retailer and organizational characteristics, results of the store observation, and retailer willingness to implement healthy store strategies.

Results

Retailer and organizational characteristics

Most retailers were male and over half completed some college or more (Table 1). Stores were either convenience with gas stations (63.6%) or convenience/small grocery stores (34.5%). About half of stores accepted SNAP benefits and 7.3% accepted WIC. All stores sold low-calorie beverages, sugar-sweetened beverages, candy and cigarettes. The vast majority sold smokeless tobacco and cigars/cigarillos, while 72.2% sold e-cigarettes. Fresh fruits were sold at 30.2% of stores, but only 9.4% sold fresh vegetables. Only 27.8% sold whole wheat bread and 42.6% sold skim or low-fat milk. In contrast, most stores sold white bread (83.3%) and whole milk (81.5%).

Table 1.

Retailer and store characteristics, Eastern North Carolina, 2014; n=55 retailers; n=54 store observations

| n (%) or median (range)

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Retailer characteristics | ||

| Male | 40 | 72.7% |

| Age, years | 38.5 | 19 –77 |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 25 | 46.3% |

| Some college | 10 | 18.5% |

| College graduate | 19 | 35.2% |

| Organizational characteristics | ||

| Convenience with gas station | 35 | 63.6% |

| Convenience/small grocery | 19 | 34.5% |

| SNAP authorized | 29 | 52.7% |

| WIC authorized | 4 | 7.3% |

| Food/beverages sold | ||

| Sugar-sweetened beverages (e.g., cola, fruit drinks, sweetened tea) | 54 | 100.0% |

| Low-calorie beverages (water, diet soft drinks) | 54 | 100.0% |

| Candy | 54 | 100.0% |

| White bread | 45 | 83.3% |

| Whole wheat bread | 15 | 27.8% |

| Whole milk | 44 | 81.5% |

| Skim milk or low fat milk (1% or 2 %) | 23 | 42.6% |

| Fresh fruits | 16 | 30.2% |

| Fresh vegetables | 5 | 9.4% |

| Tobacco products sold | ||

| Cigarettes | 54 | 100.0% |

| Smokeless tobacco | 52 | 96.3% |

| Cigars or cigarillos | 51 | 94.4% |

| E-cigarettes | 39 | 72.2% |

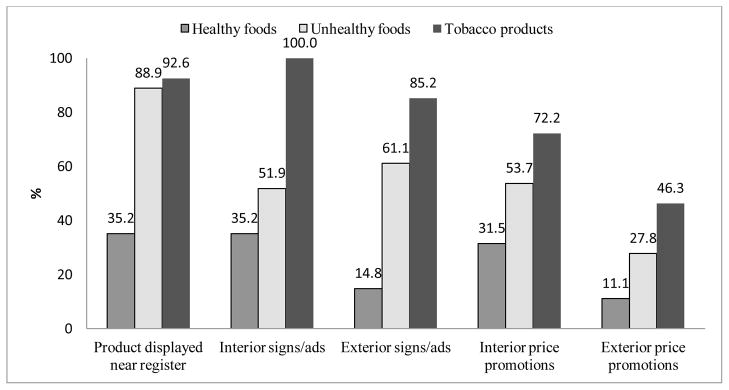

Food and tobacco marketing, display and promotions

Figure 1 shows differences in displays, ads, and promotions for healthy foods, unhealthy foods and tobacco products. A higher percentage of stores had displays near the register, signs/ads, and promotions for unhealthy foods and tobacco products compared with healthy foods. At least one unhealthy food or beverage and tobacco product was displayed near the register in almost all stores (92.6%, 88.9%, respectively), while healthy foods were displayed near the register in only a little more than a third of stores. Signs/ads for tobacco products were present inside all stores, and on the exterior of 85.2% of stores. Signs/ads for unhealthy foods were displayed inside about half of stores (53.7%) and outside 61.1% of stores, while signs/ads for healthy foods were displayed inside 35.2% of stores and outside only 14.8% of stores. Similarly, only 31.5% of stores had interior price promotions for healthy foods while 53.7% had promotions for unhealthy foods and 72.2% had interior promotions for tobacco products.

Figure 1.

Percentage of stores (n=54) with displays, ads and price promotions for healthy foods, less healthy foods and tobacco products. Healthy foods: low calorie beverages, whole wheat bread, low fat milk, fruits, vegetables; unhealthy foods: sugar sweetened beverages, candy, whole milk, white bread; tobacco products: cigarettes, smokeless, cigars/cigarillos, e-cigarettes

Retailer willingness to implement and current practice related to healthy store strategies

Among the healthy food strategies assessed, retailers were most willing to stock skim/low-fat milk, display healthy snacks near the register, and stock whole wheat bread (Table 2). However, current practice showed that only 27.8% stocked whole wheat bread, 35.2% had healthy snacks near register and 42.6% stocked low fat milk. About half of retailers were willing to stock at least three fresh fruits and three fresh vegetables, however only 2% of stores currently stocked this amount of produce. About a third was willing to stock pre-cut or frozen fruits and vegetables, and move unhealthy food and beverage displays away from the register but fewer than 10% of the stores were currently doing so. In contrast, nearly all retailers were unwilling to reduce the availability of tobacco products or marketing. About 15% were willing to remove tobacco ads/signs outside the store, consistent with our observation of a similar percentage of stores displaying no exterior tobacco advertising. Even fewer retailers were willing to move tobacco products away from the register (5.8%) or stop selling tobacco products altogether (1.9%, or 1 out of 52 retailers). Their current practices regarding point of sale tobacco products were consistent with this unwillingness to adopt healthy store strategies regarding tobacco.

Table 2.

Retailer willingness to implementa and current practice of healthy store strategies, Eastern North Carolina, U.S., 2014

| Healthy Store Strategy | N | Willing to implement (%) | Current practice (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stock skim, 1% or 2% milk. | 53 | 73.6 | 42.6 |

| Display healthy snacks such as fruit at or next to the checkout counter | 53 | 69.8 | 35.2 |

| Stock whole wheat bread, like Nature’s Promise 100% Wheat Bread | 53 | 66.0 | 27.8 |

| Stock at least 3 choices of fresh fruits and 3 choices of fresh vegetablesc | 53 | 50.9 | 2.0 |

| Stock prepared fresh fruits or vegetables, like pre-cut apple slices or carrot sticks. | 53 | 39.6 | 8.2 |

| Stock any frozen fruits or vegetables. | 53 | 35.9 | 8.2 |

| Move soda, chips or candy displays away from the register | 53 | 34.0 | 11.1 |

| Remove ads/signs for tobacco products outside the store | 51 | 15.7 | 14.8 |

| Remove ads/signs for tobacco products inside the store. | 52 | 15.4 | 0.0 |

| Move tobacco product displays away from the register. | 52 | 5.8 | 7.4 |

| Not sell any type of tobacco product | 52 | 1.9 | 0.0 |

Percentage of retailers answering willing or very willing.

Based on store observation.

Not including potatoes, onions, lemons, or limes.

Discussion

We assessed willingness and current practices of healthy store strategies among retailers of small food stores in rural North Carolina. Our results show promise for working with retailers in rural settings to increase healthy food availability in small food stores. Although we found relatively low availability of healthy foods based on our store observations, retailers reported that they were willing to implement strategies to increase healthy food availability and promotion. We found that at least 50% of retailers reported that they were willing to stock and display lower fat milk options, display healthy snacks at the counter and to stock whole, fresh produce. Still, store observations showed that less than one-third were currently doing so. There was less interest in stocking prepared produce items and frozen fruits and vegetables. Providing retailer training and equipment to store fresh, pre-cut or frozen produce could facilitate implementing strategies, and have been offered in previous intervention studies with some success.11, 23

In contrast with healthy food strategies, we found low levels of retailer willingness to reduce dependence on tobacco products. While some supermarkets and pharmacies have stopped selling tobacco products citing ethics and benefits to customer health,24–26 voluntarily reducing dependence on tobacco products in small food stores is likely to be heavily influenced by economic factors. An average convenience store generates about $300,000 in revenue annually from tobacco products,27 and the tobacco industry uses contracts to incentivize the sale and promotion of tobacco products.29, 30 Smaller stores may rely on industry incentives to generate greater profit margins on tobacco products, and retailers have reported that they need the contracts and related incentive programs to keep prices competitive with neighboring stores.28 Because of the clout that the tobacco companies exert over retailers29 and the revenue derived from tobacco products, policies that restrict tobacco product sales and marketing at the point-of-sale may be more effective than voluntary approaches.30 In fact, tobacco retail licensing ordinances are the inspiration behind healthy food licensing ordinances.31 Implementing tobacco retailer licensing systems not only allows officials to monitor compliance with state and local laws, but also allows localities to implement further restrictions, including restricting the sale of flavored tobacco products or banning tobacco retailers within 1,000 feet of schools.32

Restrictions on tobacco products and marketing have been implemented in some U.S. cities33,34 and the city of Minneapolis has implemented a healthy foods ordinance.11 There is also movement at the federal level towards requiring SNAP authorized stores to increase their offerings of healthy food choices,35 a policy change that would increase access to healthy foods for low-income Americans. An ideal policy strategy may be to incorporate additional tobacco product restrictions into future programs or ordinances to increase healthy food availability. Stores receiving incentives or technical assistance to improve healthy food availability must also abide by restrictions on the sale, promotion and display of tobacco products and marketing at the point-of-sale.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to examine retailer willingness to implement healthy store strategies related to the sale and promotion of both healthy foods and tobacco products and to directly compare it with current practices. Our sample size did not provide enough power for us to conduct statistical analysis beyond descriptive statistics; however we obtained a similar number of participants compared with previous retailer studies.18, 36 Small food store retailers are extremely busy and difficult to recruit for on-site interviews; therefore, we tried to maximize recruitment by visiting stores up to three times and at times specified by the retailer. Due to the cross-sectional nature of our study, we are unable to assess whether retailer willingness temporally precedes the actual stocking and promotion of healthy foods within stores. It may be that stocking and promoting healthy foods leads retailers to be more willing to sell and promote healthier foods, perhaps because they sell well in their stores. Finally, our study area included three rural Counties in one state, and may not be generalizable to all rural areas.

Conclusion

Small, rural food store retailers expressed a willingness to increase the availability, and to promote and display healthy foods and beverages; but, they were not willing to voluntarily reduce the availability, promotion and display of tobacco products and marketing. Healthy foods ordinances and proposed national regulations for SNAP-authorized retailers35 that require stores to stock a minimum amount of healthy foods could be combined with restrictions on tobacco sales and marketing, given that it may be difficult to influence retailers to voluntarily reduce dependence on tobacco products and marketing. Incorporating a restriction on tobacco marketing into a federal nutrition program could have an impact at the population level on both access to healthy foods and exposure to tobacco products and marketing at the point-of-sale.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by grant number U01 CA154281 from the National Cancer Institute’s State and Community Tobacco Control Initiative. The funders had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis, writing, or interpretation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. D’Angelo serves as an expert consultant in litigation against cigarette manufacturers. Dr. Ribisl has consulted for the Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products and is a member of the Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee— the views expressed in this paper are his and not those of the FDA. Dr. Ribisl serves as an expert consultant in litigation against cigarette manufacturers. Dr. Ribisl receives royalties from a store audit and mapping system owned by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill but the tools and audit mapping system were not used in this study.

References

- 1.Patterson PD, Moore CG, Probst JC, et al. Obesity and physical inactivity in rural America. The Journal of Rural Health. 2004;20(2):151–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2004.tb00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doescher MP, Jackson JE, Jerant A, et al. Prevalence and trends in smoking: a national rural study. The Journal of Rural Health. 2006;22(2):112–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lovasi GS, Hutson MA, Guerra M, et al. Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged populations. Epidemiologic reviews. 2009;31:7–20. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp005. Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robertson L, McGee R, Marsh L, et al. A systematic review on the impact of point-of-sale tobacco promotion on smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014:ntu168. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hosler AS. Retail Food Availability, Obesity, and Cigarette Smoking in Rural Communities. The Journal of Rural Health. 2009;25(2):203–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liese AD, Weis KE, Pluto D, et al. Food store types, availability, and cost of foods in a rural environment. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(11):1916–1923. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharkey JR, Horel S, Han D, et al. Association between neighborhood need and spatial access to food stores and fast food restaurants in neighborhoods of colonias. International Journal of Health Geographics. 2009;8(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharkey JR, Dean WR, Nalty C. Convenience stores and the marketing of foods and beverages through product assortment. American journal of preventive medicine. 2012;43(3):S109–S115. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hosler AS, Kammer JR. Point-of-purchase tobacco access and advertisement in food stores. Tob Control. 2012;21(4):451–452. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai D, Wang F. Geographic disparities in accessibility to food stores in southwest Mississippi. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design. 2011;38(4):659–677. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gittelsohn J, Laska MN, Karpyn A, et al. Lessons Learned From Small Store Programs to Increase Healthy Food Access. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38(2):307–315. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.2.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gittelsohn J, Song H, Suratkar S, et al. An urban food store intervention positively affects food-related psychosocial variables and food behaviors. Health Educ Behav. 2010;37(3):390–402. doi: 10.1177/1090198109343886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavanaugh E, Green S, Mallya G, et al. Changes in food and beverage environments after an urban corner store intervention. Prev Med. 2014;65:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gittelsohn J, Rowan M, Gadhoke P. Interventions in small food stores to change the food environment, improve diet, and reduce risk of chronic disease. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2012;9:11_0015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liberato S, Bailie R, Brimblecombe J. Nutrition interventions at point-of-sale to encourage healthier food purchasing: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):919. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bodor JN, Ulmer VM, Dunaway LF, et al. The Rationale behind Small Food Store Interventions in Low-Income Urban Neighborhoods: Insights from New Orleans. Journal of Nutrition. 2010;140(6):1185–1188. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.113266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gittelsohn J, Franceschini MCT, Rasooly IR, et al. Understanding the Food Environment in a Low-Income Urban Setting: Implications for Food Store Interventions. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 2008;2(2):33–50. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andreyeva T, Middleton AE, Long MW, et al. Food retailer practices, attitudes and beliefs about the supply of healthy foods. Public Health Nutrition. 2011;14(06):1024–1031. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011000061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitts SBJ, Bringolf KR, Lloyd CL, et al. Peer Reviewed: Formative Evaluation for a Healthy Corner Store Initiative in Pitt County, North Carolina: Engaging Stakeholders for a Healthy Corner Store Initiative, Part 2. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2013:10. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Economic Research Service (ERS) USDoAU. Food Desert Locator. 2012 Available: http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-desert-locator.aspx.

- 21.U.S. Census Bureau. State and County Quick Facts. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, et al. Nutrition Environment Measures Survey in Stores (NEMS-S):: Development and Evaluation. American journal of preventive medicine. 2007;32(4):282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayala GX, Baquero B, Laraia BA, et al. Efficacy of a store-based environmental change intervention compared with a delayed treatment control condition on store customers’ intake of fruits and vegetables. Public Health Nutrition. 2013;16(11):1953–1960. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013000955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDaniel PA, Malone RE. Why California retailers stop selling tobacco products, and what their customers and employees think about it when they do: case studies. BMC Public Health. 2011:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDaniel PA, Malone RE. “People over Profits”: Retailers Who Voluntarily Ended Tobacco Sales. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85751. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brennan TA, Schroeder SA. Ending Sales of Tobacco Products in Pharmacies. Jama. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D’Angelo H, Rose SW, Ribisl KM. Retail tobacco product sales volume and market share in the United States, 1997 to 2007. Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco; Philadelphia, PA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.John R, Cheney MK, Azad MR. Point-of-sale marketing of tobacco products: taking advantage of the socially disadvantaged? Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2009;20(2):489–506. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.New Product Introduction Through Point-of-Purchase. 2014 Bates: 500164188-500164208 Available: http://tobaccodocuments.org/youth/AmCgRJR19780323.Pr.html.

- 30.Lange T, Hoefges M, Ribisl KM. Regulating tobacco product advertising and promotions in the retail environment: a roadmap for states and localities. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2015;43(4):878–896. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLaughlin I, Kramer K. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2012. Peer Reviewed: Food Retailer Licensing: An Innovative Approach to Increasing Access to Healthful Foods; p. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLaughlin I. Tobacco Control Legal Consortium. License to kill: tobacco retailer licensing as an effective enforcement tool. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spielman F. City snuffs out sales of menthol cigarettes near schools. Chicago Sun-Times; Chicago: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.CounterTobacco. Stores Near Schools. Available: http://countertobacco.org/stores-near-schools.

- 35.Food and Nutrition Service; U.S. Department of Agriculture, editor. Federal Register. 2016. Enhancing Retailer Standards in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) pp. 8015–8021. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ayala GX, Laska MN, Zenk SN, et al. Stocking characteristics and perceived increases in sales among small food store managers/owners associated with the introduction of new food products approved by the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(9):1771–1779. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012001255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]