Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this pilot study was to examine preliminary feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of a toolkit (Parent And Caregiver Active Participation Toolkit) to increase parent participation in community-based child mental health services.

Method

Study participants included 29 therapists (93% female; mean age 34.1 years; 38% Latino) and 20 parent/child dyads (children 80% female with a mean age of 8.6 years; parents 40% Latino) in six diverse community mental health clinics. Therapists were randomly assigned to standard care or the toolkit with standard care. Therapist and parent survey data and observational coding of treatment sessions were utilized.

Results

Mean comparisons and repeated measures analyses were used to test differences between study conditions over four months. Results supported preliminary feasibility and acceptability of the toolkit, with therapists assigned to the toolkit participating in ongoing training, adhering to toolkit use, and perceiving the toolkit as feasible and acceptable within their setting. Results preliminarily demonstrated improvement in therapists’ job attitudes as well as actual use of parent engagement strategies. Results also preliminarily demonstrated increases in parent participation in child therapy sessions, more regular attendance, as well as some indication of support for perceived treatment effectiveness.

Conclusions

Overall, results suggest the feasibility, acceptability, and potential effectiveness of the toolkit to enhance therapist job attitudes, practices that support parent engagement, parent engagement, and consumer perspectives on treatment outcomes and the potential promise of future research in the area of parent participation interventions in child mental health services.

Keywords: parent engagement, parent participation, toolkit, community-based child mental health services

Treatment engagement is critical for effective and efficient child/family mental health (MH) service delivery. Parent or caregiver (hereafter referred to as parent) engagement is of particular importance given parents often serve both as gatekeepers to MH care and the target of intervention themselves, especially in most evidence-based practices (EBPs) for disruptive behavior disorders (Eyberg, Nelson, & Boggs, 2008), the most common disorders in community-based MH services (Garland et al., 2001). While attendance is the most commonly-used indicator of engagement (Becker et al., 2015), parent participation in treatment, including meaningful interactions with the child’s therapist and follow-through with recommendations, is an important element of engagement (Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015). Meta-analyses show improvements in child outcomes when parents are involved in treatment (Dowell & Ogles, 2010).

The Mental Health Services Ecological (MHSE) model (e.g., Rodriguez, Southam-Gerow, O’Connor, & Allin, 2014) is a useful framework for conceptualizing the importance of parent participation engagement (PPE) within community-based services, describing the multiple levels of influence (client/family, therapist, organization, service system) on service delivery and implementation of EBPs. At the client/family level, parents and children report desiring greater parent involvement in services (Baker-Ericzén, Jenkins, & Haine-Schlagel, 2013; Rodriguez et al., 2014). At the therapist level, therapists do not involve parents the majority of the time (Haine-Schlagel, Brookman-Frazee, Fettes, Baker-Ericzén, & Garland, 2012) and rarely assign or review parent-focused homework (Garland et al., 2010). At the organization level, PPE has varied by organization (Haine-Schlagel et al., 2015) and positive staff attitudes and organizational climate have been associated with adult client engagement (e.g., Broome, Flynn, Knight, & Simpson, 2007). At the service system level, policy makers highlight patient-centered care and client engagement as critical components of quality health care (Institute of Medicine, 2015).

Existing interventions to increase PPE in child MH services have typically focused on the therapist or client/family levels. Reviews of therapist-focused engagement interventions demonstrate effectiveness for attendance outcomes, but the literature has not focused on participation outcomes (Becker et al., 2015). A small number of interventions also center on improving parents’ ability to participate (e.g., Olin et al., 2010). However, both intervention types are limited in effectiveness given their focus on only one stakeholder. Models for targeting therapists and parents concurrently are needed to optimally increase PPE in community-based services (Polo, Alegría, & Sirkin, 2012).

Parent And Caregiver Active Participation Toolkit (PACT)

The Parent And Caregiver Active Participation Toolkit (PACT; Haine-Schlagel & Bustos, 2013) was developed to address the need for tools to increase PPE and for strategies that target both therapists and parents (Table 1). PACT includes a set of linked therapist and parent tools to increase PPE in MH services for disruptive behavior problems in children ages 4–13, an age group commonly served in community-based services and for which parent involvement is clinically indicated. For example, PACT incorporates both therapist training on how to increase opportunities for parents to ask questions and supports for parents to ask questions. Community stakeholders provided input on PACT’s development.

Table 1.

Description of Parent And Caregiver Active Participation Toolkit (PACT).

| Tool | Description | Examples of Empirical Basis |

|---|---|---|

| ACEs Training | Training on ten evidence-based engagement strategies for every session to build Alliance, Collaboration, and Empowerment (ACEs): (1) Reflectively listen; (2) Convey parent-therapist partnership; (3) Communicate positive regard; (4) Give suggestions, not directions; (5) Ask for input on intervention strategies; (6) Incorporate input into sessions; (7) Involve parent in session activities; (8) Collaboratively plan homework; (9) Focus on strengths and effort; (10) Jointly identify/problem solve barriers. | -Alegría et al., 2008 -Becker et al., 2015 -McKay et al., 1998 -Olin et al., 2010 |

| DVD | 27-minute video with testimonials from parents and therapists. Includes built-in prompts to complete Workbook Activities (see below). Six chapters: Introduction: What is PACT & How Can it Help?; #1: Why is Participation Important?; #2: You Have Many Strengths as a Parent; #3: How Do You Feel About Participating?; #4: Participation: Speak Up; #5: Participation: Take Action. Parents watch during early sessions (typically 3–4 sessions) in lobby. | -Self-Brown & Whitaker, 2008 |

| Workbook | Information about PACT, participation tips, and four Activities linked to DVD content (e.g., DVD chapter on parent strengths linked to workbook activity parents complete on their strengths) parents complete during early sessions in lobby while viewing DVD and later review with therapist. Activities include: 1) My Point of View, 2) I Have Strengths as a Parent, 3) How Do I Feel About Participating in Therapy?, and 4) Speaking Up With My Child’s Therapist. Parents return Activities to therapist, who utilizes the ACEs to reinforce and expand content. | -Alegría et al., 2008 -McKay et al., 1998 -Nock & Kazdin, 2005 |

| Action Sheet | Worksheet for use in every session (in duplicate form). Helps therapist, parent, and child collectively review planned homework from previous session, session goals/topics, and decisions on future homework. | -Becker et al., 2015 |

| Messages | Brief motivational messages sent to parent between every session via email, voice mail, text, or note per parent’s choice. Four categories: general motivation to participate, attendance, speak up, and take action. | -Murray, Woodruff, Moon, & Finney, 2015 |

| Training Package | 1) Manual with training vignettes and electronic materials, 2) 8-hour in-person workshop with continuing education credits, 3) Eight 1-hour group consultations via live webinar and 1–2 individual phone consultations with performance-based feedback over 4 months, 4) Weekly training tips sent via text or email. | -Nadeem, Gleacher, & Beidas, 2013 |

Current Study

The purpose of the current study is to examine preliminary feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of PACT on therapist and parent/child level outcomes. Hypotheses include: 1) PACT will be feasible and acceptable in community-based settings and therapists will meet PACT implementation benchmarks; 2) PACT therapists will report more positive job attitudes and demonstrate more extensive use of engagement strategies than standard care (SC) therapists; 3) PACT parents will demonstrate increased in-session participation and session attendance; and 4) PACT families will report enhanced symptom and consumer perspective outcomes (Hoagwood et al., 2012).

Method

Participants

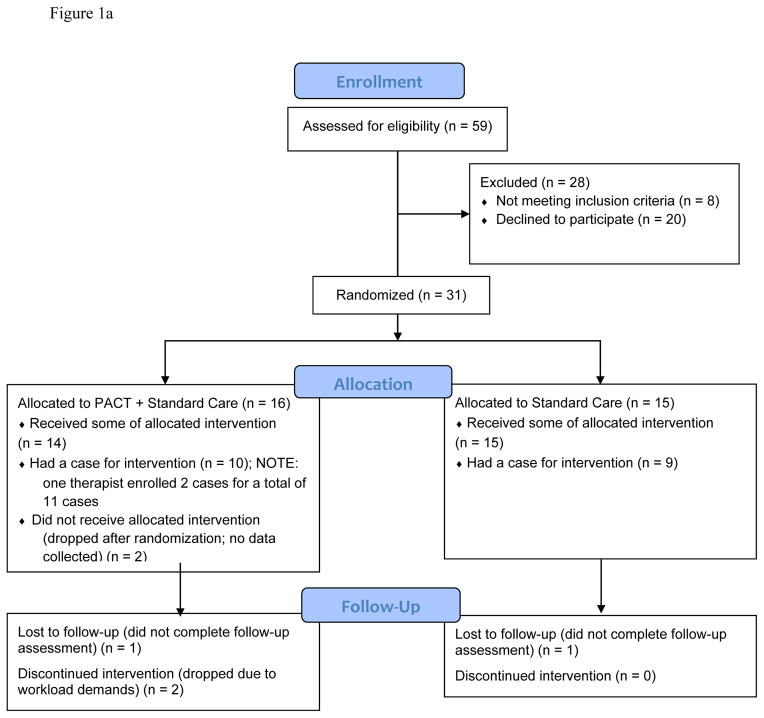

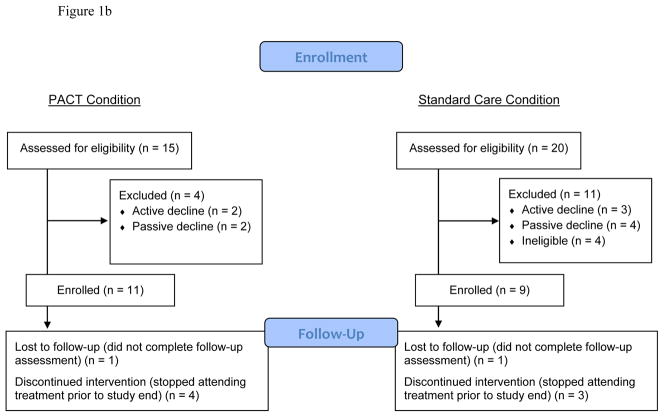

Study participants included 29 therapists and 20 parent/child dyads (Figures 1a/1b) from six community-based MH clinics that serve low-income, urban and rural, racially/ethnically diverse children and their families in a large Southern California metropolitan county. Therapist inclusion criteria were: 1) employed at their agency for at least next five months, 2) provided clinic-based psychotherapy to eligible children and families, and 3) planned to start a new episode of care with an eligible parent-child dyad during recruitment window. Therapists self-identified as 38% Latino and 93% were female with a mean age of 34.1 years (SD = 10.4). A total of 74% had a Master’s degree and 48% were Marriage and Family Therapists. The sample is generally representative of the broader population of community-based therapists nationally in terms of therapist age, gender, and educational level (Glisson et al., 2008).

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. CONSORT Flow Diagram for Therapist Participants.

Figure 1b. CONSORT Flow Diagram for Parent Participants.

Parent/child inclusion criteria included: 1) parent was legal guardian, 2) parent was English-speaking, 3) parent was at least 18 years old, 4) child was between ages 4–13, 5) parent identified disruptive behavior problems (e.g., aggression, noncompliance, delinquency) as a presenting problem for child’s treatment, and 6) parent and child attended four or fewer sessions with a participating therapist. Parents self-identified as 40% Latino; 85% were biological mothers with a mean age of 35.0 (SD = 10.7) ; 50% had a high school education or less. Their participating children were 80% male, mean age 8.7 years (SD = 2.2), with 50% having a primary clinician-assigned diagnosis of ADHD, 15% with anxiety, 10% with disruptive behavior, and 25% with mood or other. The sample is generally representative of publicly funded clients served in this region in terms of gender, ethnicity, and diagnosis (Zima et al., 2005).

Procedures

This study was conducted August 2013 through August 2014. Therapists were recruited via staff meetings, consented, and randomized to either PACT with SC (PACT) or SC using a matched coin flip by researchers. Participating therapists approached parents early in the treatment episode for permission to be contacted by the research team. Parent consent was obtained prior to any data collection and child assent was obtained for children 7 years or older.

Data analyzed in the current study include baseline surveys, therapist-reported monthly surveys, video-recordings of therapy sessions, and four-month follow-up surveys (therapist data collected electronically; parent data collected in-person or by phone). PACT and SC therapists received $45 and $30, respectively; PACT and SC parents received up to $50 and $35, respectively; therapists and parents were entered into monthly drawings each worth $10. Study procedures were approved by two Institutional Review Boards.

As a randomization check, differences on therapist demographics by study condition were examined and revealed a significant association between therapist-reported ethnicity and study condition, with more Latino/Hispanic therapists in PACT than SC. In addition, parent and child demographics were compared and analyses revealed significantly more younger children enrolled in PACT than SC.

PACT condition

PACT is designed for use within standard care and targets therapists and parents simultaneously (Table 1). A 4-month window was selected for PACT delivery given the median length of EBPs for disruptive behaviors and of community-based care (Garland et al., 2010; Garland, Hawley, Brookman-Frazee, & Hurlburt, 2008).

SC condition

SC therapists agreed to use their regular treatment procedures. While no data were collected regarding the content of care provided (e.g., strategies implemented, use of EBPs), previous research in these settings (Garland et al., 2010) and anecdotal impressions from research staff indicate highly eclectic care with a combination of child and parent-focused strategies. Several strategies were employed to minimize contamination risk among therapists across study conditions within agencies; no instances of contamination were identified.

Measures

Sociodemographics

At baseline, therapists reported on sociodemographics including gender, age, race, ethnicity, education level, background, and training. Parents reported on sociodemographics about themselves and their participating child.

Feasibility/Acceptability

Therapist attendance at the initial training and individual and group consultations was tracked. Therapists completed a 35-item Likert scale measure developed for this study to assess perceptions of PACT (1-Strongly Disagree to 5-Strongly Agree; higher scores indicating more positive perceptions). The three subscales used here include toolkit satisfaction (11 items; α = .92), training satisfaction (11 items; α = .88), and future use plans (3 items; α = .70).

Adherence

See Table 2 for a list of therapist adherence measures.

Table 2.

Therapist adherence measures.

| Adherence Measure |

|---|

| -Number of parent engagement strategies (ACEs) used per individual consultation feedback form (possible range: 0–9) -Therapists’ report of ACEs strategies used across the past month rated on a Likert scale from 1–5 (up to three months of data were collected and scores were averaged by therapist) -Observed extensiveness of use of ACEs strategies (scale from 0–6) -Whether the therapist met toolkit implementation benchmarks (submitted all four completed Activities, submitted at least three completed Action Sheets, ordered at least three Messages; see Table 1) |

Note: ACEs=Therapist Alliance, Collaboration, and Empowerment Strategies Observational Coding System; implementation benchmarks were decided based on the approximate number of sessions needed to complete the DVD and Workbook, when the most intensive dose of PACT is being delivered.

Intervention effects: Therapist attitudes and practices

Two measures were utilized.

Texas Christian University Survey of Organizational Functioning (TCU-SOF; (Lehman, Greener, & Simpson, 2002)

Four subscales of the TCU-SOF provider-report measure were adapted and administered to therapists at baseline and follow-up to assess job attitudes: Efficacy, Influence, Adaptability, Satisfaction. The original measure has strong psychometric properties (Lehman et al., 2002) and subscales were selected based on relevance and associations with adult engagement (Broome et al., 2007). Each Likert scale item is rated 1-Disagree Strongly to 5-Agree Strongly. Subscales demonstrated adequate to good internal consistency at baseline (M of α’s = .73; range = .61–.82). For two subscales (Efficacy and Adaptability) below the conventional .70 cutoff, item-to-total correlations were examined (Clark & Watson, 2003). All correlations were all moderate to large, (M of r’s = .67, range = 57–.74 and M of r’s = .68, range = .57–.75, respectively).

Therapist Alliance, Collaboration, and Empowerment Strategies (ACEs) Observational Coding System (Haine-Schlagel & Martinez, 2014a)

A 10-item observational coding system was developed to measure therapists’ in-session use of parent engagement strategies (Table 3). The coding system captures extensiveness, reflecting frequency and thoroughness of each strategy’s use. Each code is rated on a 7-point Likert scale (0–6) with higher numbers indicating greater extensiveness; coders were masked to study condition. Therapists submitted recordings for up to four months. A total of 126 recordings were received (PACT = 71, SC = 55) and 93 were selected for coding: 1) first four sessions after parent/child dyad study enrollment, 2) three middle sessions approximately one month apart, and 3) final session collected. Of these, 28 (30.1%) were double-coded for inter-rater reliability using intraclass correlations (ICCs). Two codes were dropped from analyses due to low inter-rater reliability (Empowerment: Addressed barriers to parent participation) or extremely low rate of occurrence (Collaboration: Therapist involved parent in therapeutic activities). ICCs for remaining codes were fair to excellent (Cicchetti, 1994; Table 6). Extensiveness ratings were averaged across sessions for each parent/child dyad. In this study, only the first four coded treatment sessions after study consent were examined, which represents implementation of the most intensive dose of PACT (DVD and Workbook).

Table 3.

Intra-class correlations (ICC’s) for observational codes (ACEs & PPE) in current study.

| Code | ICC |

|---|---|

| ACEs | |

| Alliance | |

| Therapist actively listened to parent’s perspectives | .64 |

| Therapist conveyed parent-therapist partnership in child’s therapy | .75 |

| Therapist communicated positive regard to parent | .51 |

| Collaboration | |

| Therapist offered suggestions about therapeutic tasks | .79 |

| Therapist sought out parent input | .60 |

| Therapist incorporated parent’s input into therapeutic tasks | .52 |

| Therapist attended to parent home actions | .44 |

| Empowerment | |

| Therapist recognized parent strengths and effort to participate in child’s therapy | .66 |

| PPE | |

| Parent shared his/her perspectives in general | .60 |

| Parent shared his/her perspective about home actions | .61 |

| Parent appeared to agree with/be enthusiastic about home actions | .51 |

| Parent asked the therapist questions | .72 |

| Parent demonstrated a commitment to therapy | .69 |

Note: ACEs: Therapist Alliance, Collaboration, and Empowerment Strategies Observational Coding System; PPE: Parent Participation Engagement in Child Psychotherapy Observational Coding System; only codes included in the current study are listed here.

Intervention effects: Parent participation

Three measures were utilized.

Parent Participation Engagement (PPE) in Child Psychotherapy Observational Coding System (Haine-Schlagel & Martinez, 2014b)

A 6-item observational coding system was developed for this study to measure in-session PPE. Each code is rated on a 5-point Likert scale with higher numbers indicating greater participation. ICCs were fair to good (M of ICCs = .63; range = .51–.72; Table 3; Cicchetti, 1994). One code, Participated in therapy activities, was dropped due to low rate of occurrence. In this study, only sessions coded after the fourth session post-study consent were examined, following the most intensive delivery of PACT.

Engagement Measure (Hall, Meaden, Smith, & Jones, 2001)

This 11-item therapist-report measure of parent engagement has strong psychometric properties (Hall et al.) and was completed at follow-up, with higher scores representing greater perceived engagement (α = .96). Each Likert scale item is rated 1-Never to 5-Always. The measure was adapted to apply to parents, and one item was eliminated because it was not applicable to the study’s psychotherapy context.

Parent/child dyad attendance

A therapist-reported ratio was calculated based on the number of in-person sessions attended (on time or late) to the total of number of in-person sessions scheduled (no shows, cancellations, and sessions attended on-time or late) over four months.

Intervention effects: Treatment outcomes

Child symptomatology and perceived treatment effectiveness were assessed.

Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI; Eyberg & Pincus, 1999)

The ECBI, a 36-item parent-reported measure of frequency and intensity of child disruptive behaviors with strong psychometric properties (Eyberg & Pincus), was administered at baseline and follow-up. Internal consistency of the intensity subscale (items rated on a 7-point Likert scale from Never to Always) used in this study was strong (α = .93 at baseline).

Multidimensional Adolescent Satisfaction Scale (MASS; Garland, Saltzman, & Aarons, 2000)

The 4-item perceived treatment effectiveness subscale of the parent-report version has strong psychometric properties (Haine-Schlagel, Fettes, Garcia, Brookman-Frazee, & Garland, 2014) and was administered at follow-up. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale, with higher scores representing greater perceived effectiveness (α = .73 in this sample).

Data Analytic Procedures

All available therapist and parent level data were included unless noted. Feasibility and adherence analyses were conducted using SPSS (v.22). Initially, the associations between therapist ethnicity and therapist-focused outcomes and between child age and parent/child dyad-focused outcomes were examined in SPSS to address these observed group differences. No significant associations were found. To examine differences between study conditions, independent samples t-tests were conducted in SPSS. Study hypotheses involving Group (PACT vs. SC) by Time (baseline to follow-up) effects were conducted in Mplus, using the maximum likelihood with robust standard errors estimation procedure, adjusting for missing data and non-normality of the outcome. No significant associations were found between participant missing data and demographics. Of primary interest were cross-level Group X Time interaction terms representing the intervention effects. For significant Group X Time interactions, within condition changes in scores from baseline to follow-up were evaluated.

Results

Given the pilot nature of this work and small sample size, for the intervention effects, significant results (p < .05), marginal trends (p < .10), and nonsignificant effects with moderate to large effect sizes (Cohen’s d > .50; Cohen, 1988) are noted.

Feasibility/Acceptability

All 14 PACT therapists (100%) attended the introductory workshop. Average group consultation attendance was 6.07 (SD = 2.84; possible range 0–8), and 100% of therapists who enrolled a parent/child dyad attended the individual consultation. Average therapist ratings on feasibility and acceptability (possible range 1–5) were 4.17 (SD = .60) for toolkit satisfaction, 4.05 (SD = .60) for training satisfaction, and 4.06 (SD = .59) for future use plans.

Adherence

Trainer-rated ACEs strategy use across the 10 PACT therapists with recordings averaged 7.40 (SD = 1.17).1 Therapist-rated intensity of ACEs strategy use averaged 4.21 (SD = .39). Average observer-rated extensiveness of ACEs strategies delivery ranged up to 2.5. Therapists met PACT implementation benchmarks for 72.7% of cases (n = 8 out of 11). Nonadherent cases (n = 3) were due to the family dropping out of care.

Intervention Effects: Therapist Attitudes and Practices

Therapist job attitudes

Analyses revealed a statistically significant Group X Time interaction for Adaptability and a marginally significant Group X Time interaction for Influence (Table 4a). Follow-up analyses found a trend for an increase in Adaptability for PACT (t = 1.81, p = .07; medium effect), but a nonsignificant decrease in SC (t = −1.17, p = .24; small effect). Follow-up analyses for Influence found a statistically significant increase for PACT (t = 5.18, p < .001; small effect), but a nonsignificant difference in SC (t = −.13, p = .90; zero effect). Although not significant and neither within-group effect size was notable, a medium effect was observed between PACT and SC for Satisfaction. No Group X Time interaction was detected for Efficacy.

Table 4a.

Intervention effects on therapist job attitudes (PACT vs. SC).

| Measure/Subscale | PACT (n=14)a | SC (n=15)a | B | p | 95% CI of B Estimate | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL M (SD) | FU M (SD) | BL M (SD) | FU M (SD) | |||||

| TCU | ||||||||

| Efficacy | 39.86 (4.54) | 41.46 (4.20) | 40.0 (4.72) | 40.29 (3.58) | −1.10 | .45 | −3.94–1.74 | TK=.37 SC=.07 |

| Influence | 35.71 (5.26) | 37.27 (2.50) | 38.67 (6.24) | 38.69 (6.80) | −2.27 | .05 | −4.57–0.04 | TK=.38 SC=.00 |

| Adaptability | 37.32 (4.75) | 39.55 (4.72) | 39.50 (6.21) | 37.86 (6.03) | −3.99 | .04 | −7.86–−0.12 |

TK=.47 SC=−.27 |

| Satisfaction | 41.79 (5.75) | 44.39 (4.73) | 44.44 (4.16) | 44.17 (3.68) | −1.27 | .11 | −2.81–0.28 | TK=.49 SC=−.07 |

Note: Effects significant at p<.05 are bolded. PACT=toolkit condition; SC= toolkit + standard care condition (coded as PACT=0; SC=1); BL=Baseline; FU=Follow-Up; TCU=Texas Christian University Survey of Organizational Functioning.

These analyses reflect an intent-to-treat model whereby all cases with baseline data were included (see Figure 1a/1b).

Therapist observed engagement strategies.2

PACT therapists received significantly higher extensiveness ratings than SC therapists for Collaboration-attend to parent home actions and Empowerment-recognize parent strengths and effort across the first four sessions (Table 4b). Results also found a medium effect size for Collaboration-seek input.

Table 4b.

Intervention effects on therapist practices (PACT vs. SC).

| Measure/Subscale | PACT (n=11)a | SC (n=7)a | t(16) | p | 95% CI of Mean Diff | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |||||

| ACEs Coding System | ||||||

| A - Active Listening | 2.54 (0.99) | 2.64 (1.65) | −0.17 | .87 | −1.41–1.20 | −0.08 |

| A - Partnership Language | 2.30 (1.34) | 1.79 (1.33) | 0.80 | .44 | −0.85–1.89 | 0.38 |

| A - Positive Regard | 1.33 (0.64) | 1.50 (0.99) | −0.46 | .66 | −0.99–0.64 | −0.20 |

| C - Make Suggestions | 2.21 0(.70) | 2.36 (1.27) | −0.33 | .75 | −1.13–0.83 | −0.16 |

| C - Seek Input | 2.30 (1.09) | 1.68 (0.73) | 1.33 | .20 | −0.37–1.62 | 0.67 |

| C - Incorporate Input | 0.54 (0.52) | 0.54 (0.60) | 0.01 | .99 | −0.56–0.57 | 0.00 |

| C - Home Actions | 1.80 (1.03) | 0.64 (0.38) | 3.40 | .00 | 0.43–1.90 | 1.49 |

| E - Strengths and Effort | 2.52 (0.96) | 1.25 (0.69) | 3.03 | .01 | 0.38–2.17 | 1.52 |

Note: Effects significant at p<.05 are bolded. PACT=toolkit condition; SC= toolkit + standard care condition; ACEs=Therapist Alliance, Collaboration, and Empowerment Strategies Observational Coding System; A=Alliance strategies; C=Collaboration strategies; E=Empowerment strategy.

These analyses include only those cases where the therapist had a case for intervention (see Figure 1a) and recordings of any of the first four therapy sessions after study consent were submitted (no cases are missing for PACT therapists and two cases are missing for SC therapists); one PACT therapist had two cases and the results (not presented here) were not different when the second case was excluded.

Intervention Effects: Parent Participation

Observed parent participation engagement

PACT parents received significantly higher ratings than SC parents for Share perspective about home actions (Table 5). Although not statistically significant, trends were observed for Ask therapist questions and Agreement with/enthusiasm for home actions, with PACT parents’ extensiveness ratings somewhat higher than SC parents.3

Table 5.

Intervention Effects on Parent Participation (PACT vs. SC).

| Measure/Subscale | PACT | SC | t | p | 95% CI of Mean Diff | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |||||

| PPE Coding System | n=6a | n=6a | ||||

| Share perspective general | 3.60 (.94) | 3.42 (.49) | t(10)=0.42 | .69 | −0.79–1.15 | .24 |

| Share perspective home actions | 3.49 (.67) | 2.50 (.50) | t(9)=2.71 | .02 | 0.16–1.81 | 1.67 |

| Enthusiasm home actions | 2.76 (.65) | 2.00 (.71) | t(9)=1.87 | .09 | −0.16–1.69 | 1.12 |

| Ask questions | 2.25 (.42) | 1.83 (.26) | t(10)=2.08 | .07 | −0.03–0.86 | 1.20 |

| Commitment to therapy | 3.25 (.47) | 2.93 (1.09) | t(10)=0.66 | .53 | −0.76–1.40 | .38 |

| Overall Engagement-Therapist | n=8 | n=8 | ||||

| Engagement Measure | 42.78 (3.88) | 37.56 (12.64) | t(14)=1.12 | .28 | −4.81–15.25 | .56 |

| Attendance | n=11 | n=8 | ||||

| Ratio—Attended:Scheduled | .91 (.10) | .81 (.12) | t(17)=1.93 | .07 | −0.01–.21 | .91 |

Note: Effects significant at p<.05 are bolded. PACT=toolkit condition; SC= toolkit + standard care condition; PPE = Parent Participation Engagement (PPE) in Child Psychotherapy Observational Coding System.

These analyses include only those cases where recordings of therapy sessions were submitted (total eligible cases are 11 for PACT and 7 for SC) after the fourth session post-study enrollment (five PACT cases and one SC case are missing data due to dropping from treatment prior to this time frame); no significant differences on participant demographics between those parent/child dyads that dropped from treatment compared with those that remained were detected, either overall or within condition; one PACT therapist had two cases and the results (not presented here) were not different when the second case was excluded.

Therapist-reported parent engagement

Although not statistically significant, a medium effect was found with PACT parents reporting somewhat higher total scores than SC parents (Table 5).

Attendance

Although not statistically significant, a trend was found as PACT parent/child dyads attended somewhat more scheduled sessions compared with SC parents/children (Table 5).

Intervention Effects on Treatment Outcomes3

Child symptomatology

Analyses revealed no effect for the Group X Time interaction (B = 6.13; p = .60; PACT d = .24; SC d = .23).

Perceived effectiveness

Although not statistically significant, analyses revealed a medium effect in which PACT parents reported somewhat higher total scores compared with SC parents (t = 1.32; p = .205; d = .62).

Discussion

Overall, results from this randomized pilot study provide preliminary support for the feasibility and potential effectiveness of PACT when utilized in community-based MH clinics. As hypothesized, findings provide some evidence that PACT therapists participated in ongoing training, utilized PACT as intended, and perceived PACT as feasible and acceptable to utilize. Also, as hypothesized, results demonstrate some preliminary evidence of improvements in PACT therapists’ job attitudes and utilization of parent engagement strategies compared to SC therapists. PACT families, as hypothesized, demonstrated some increased parent participation behaviors following the most intensive dose of PACT, tended to attend more sessions, and to a degree perceived treatment as more effective than SC families.

Results provide preliminary support for the feasibility and acceptability of PACT implementation in community-based settings, which is consistent with mixed methods results from multiple stakeholders (parents, therapists, and program managers; Haine-Schlagel, Mechammil, & Brookman-Frazee, under review). Results also suggest therapists generally adhered to utilizing engagement strategies and delivered the full toolkit with families remaining in their care. These pilot study results provide some early indication that PACT may be a useful intervention to optimize the MHSE model of service delivery and EBP implementation (Rodriguez et al., 2014). For example, preliminary evidence of improved job attitudes in PACT therapists may indicate that PACT can predispose community-based therapists to be more receptive to innovations such as EBPs.

Although path analyses could not be conducted due to limited sample size, preliminary results suggest a temporal synergy between changes in therapist practices and parent participation in sessions, consistent with documented links and increases in participation over time (Bamburger, Coatsworth, Fosco, & Ram, 2014; Jungbluth & Shirk, 2013). The results preliminarily indicate that an early, brief, intensive dose of attention to PPE may set a positive course for participation over time. In addition, treatment outcome results, while minimal, suggest that an intervention designed to increase parent participation may perhaps enhance parents’ perceptions of treatment effectiveness.

Limitations and Strengths

These pilot study results may be interpreted as an indication of the potential promise of this area of research and a call for additional attention to developing and implementing strategies to encourage PPE in complex community-based contexts. However, several study limitations suggest caution in interpreting results. Due to the pilot nature of this work, the small sample size makes it difficult to detect significant effects and to generalize findings. Although several large effect sizes were detected, the nonsignificance of many analyses and fairly large number of tests run indicates the possibility that results may be due to chance or overly influenced by outliers. Also, to maximize power, all available data were included, requiring analyses to utilize different subsamples, which may make the interpretation of findings challenging. Further, the small sample size precluded controlling for covariates (i.e., child, parent, therapist level variables) that may be associated with the outcomes of interest (Stadnick, Haine-Schlagel, & Martinez, under review) and examining clinic-level differences that may be important given observed program-level variability in PPE (Haine-Schlagel et al., 2015).

A second limitation is the greater attrition from treatment in the PACT condition, which may represent less engaged parents in the PACT condition stopping treatment earlier. However, post-hoc analyses comparing PACT parents who remained in treatment versus those who ended treatment by the fourth session on other participation indicators did not find differences between subgroups. Further, reasons for dropping treatment do not indicate a lack of engagement, with PACT parents reporting the following: insurance changed, child shifting to school-based services, and therapist on leave; the one SC parent reported the therapist leaving the clinic as the reason. A third limitation is the inability of two participating PACT therapists to recruit a family into the study despite reported enthusiasm for the study and participation in group consultations. These therapists may have differed in some unmeasured way regarding attitudes and/or ability that could impact generalizability of the results. Fourth, participating therapists may be subject to selection effects that may limit generalizability; this study did not collect data on therapists who declined to participate. Fifth, while the ICC’s for the observational codes are acceptable, caution should be applied when interpreting those results.

Despite these limitations, several study strengths should also be noted. First, PACT is the first engagement intervention focusing on both the client/family and therapist levels of the MHSE model simultaneously and providing tools for use in ongoing care. Second, participants were highly diverse and the care provided was highly eclectic, supporting potential generalizability of findings to diverse populations of therapists, families, and clinic-based services. Third, the development of reliable observational coding systems of in-session therapist practices and parent participation is a notable strength, as are the multiple indicators of parent engagement. Fourth, randomization to study condition eliminated selection bias and maximized interpreting the preliminary findings as causally related.

Future Directions

The next step is to conduct a well-powered effectiveness trial of PACT in community-based settings. In addition, research is needed to identify whether/how PACT can be appropriate for other settings (e.g., schools, homes). Future large-scale studies can also assess for whom PACT worked best. Anecdotally, PACT therapists perceived the toolkit as most useful for families with engagement challenges. Given a link between higher motivation at baseline and higher participation in sessions across conditions (Stadnick et al., in press), examining moderators of PACT effectiveness may allow for a profile of those families most in need of participation interventions.

This randomized pilot study of PACT within standard community-based care for diverse families provides preliminary support for its feasibility, acceptability, and potential effectiveness. Results support the need for a large randomized controlled trial to further evaluate implementation and effectiveness outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23MH080149 (PI: Haine-Schlagel). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to acknowledge Ann Garland, Ph.D., Mary McKay, Ph.D., Lauren Brookman-Frazee, Ph.D., and Amy Drahota, Ph.D. for their contributions to the project as well as the participating clinics, therapists, and families. The authors also are grateful to Nicole Stadnick, Ph.D., MPH and Natalia Walsh, M.S. for reviewing an earlier version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

For the therapist who enrolled two cases (Figure 1a), only ratings for the first case are included here.

Analyses across all sessions revealed an identical pattern of findings to those presented here.

Analyses across all sessions revealed an identical pattern to those presented here, with the exception that the effect on Agreement with/enthusiasm for home actions was no longer marginally significant but the large effect size remained.

References

- Alegría M, Polo A, Gao S, Santana L, Rothstein D, Jiminez A, Normand S. Evaluation of a patient activation and empowerment intervention in mental health care. Medical Care. 2008;46(3):247–256. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318158af52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Ericzén MJ, Jenkins MM, Haine-Schlagel R. Therapist, parent, and youth perspectives of treatment barriers to family-focused community outpatient mental health services. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 2013;22(6):854–868. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9644-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamburger KT, Coatsworth JD, Fosco GM, Ram N. Change in participant engagement during a family-based preventive intervention: Ups and downs with time and tension. Journal of Family Psychology. 2014;28(6):811–820. doi: 10.1037/fam0000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker KD, Lee BR, Daleiden EL, Lindsey M, Brandt NE, Chorpita BF. The common elements of engagement in children’s mental health services: Which elements for which outcomes? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44(1):30–43. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.814543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broome KM, Flynn PM, Knight DK, Simpson DD. Program structure, staff perceptions, and client engagement in treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;33(2):149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(4):284–290. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Dowell KA, Ogles BM. The effects of parent participation on child psychotherapy outcome: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39(2):151–162. doi: 10.1080/15374410903532585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Boggs SR. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):215–237. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Pincus D. Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory and Sutter-Eyberg Student Behavior Inventory - Revised: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Brookman-Frazee L, Hurlburt M, Arnold E, Zoffness R, Haine-Schlagel R, Ganger W. Mental health care for children with disruptive behavior problems: A view inside therapists’ offices. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61(8):788–795. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.8.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Hawley KM, Brookman-Frazee L, Hurlburt MS. Identifying common elements of evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children’s disruptive behavior problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(5):505–514. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816765c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Hough RL, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Wood PA, Aarons GA. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in youths across five sectors of care. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(4):409–418. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Saltzman MD, Aarons GA. Adolescent satisfaction with mental health services: Development of a multidimensional scale. Evaluation & Program Planning. 2000;23(2):165–175. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7189(00)00009-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Landsverk J, Schoenwald S, Kelleher K, Hoagwood KE, Mayberg S … Research Network on Youth Mental Health. Assessing the organizational social context (OSC) of mental health services: Implications for research and practice. Administration & Policy in Mental Health & Mental Health Services Research. 2008;35(1–2):98–113. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haine-Schlagel R, Brookman-Frazee L, Fettes DL, Baker-Ericzén M, Garland AF. Therapist focus on parent involvement in community-based youth psychotherapy. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2012;21(4):646–656. doi: 10.1007/s10826-011-9517-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haine-Schlagel R, Bustos C. Parent And Caregiver Active Participation Toolkit (PACT): Therapist manual. San Diego State University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Haine-Schlagel R, Fettes DL, Garcia AR, Brookman-Frazee L, Garland A. Consistency with evidence-based treatments and perceived effectiveness of children’s community-based care. Community Mental Health Journal. 2014;50(2):158–163. doi: 10.1007/s10597-012-9583-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haine-Schlagel R, Martinez JI. Therapist Alliance, Collaboration, and Empowerment Strategies (ACEs) Observational Coding System. San Diego State University; 2014a. [Google Scholar]

- Haine-Schlagel R, Martinez JI. Parent Participation Engagement (PPE) in Child Psychotherapy Observational Coding System. San Diego State University; 2014b. [Google Scholar]

- Haine-Schlagel R, Mechammil M, Brookman-Frazee L. Stakeholder perspectives on a toolkit to enhance caregiver participation in community-based child mental health services. doi: 10.1037/ser0000095. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haine-Schlagel R, Roesch SC, Trask EV, Fawley-King K, Ganger WC, Aarons GA. The Parent Participation Engagement Measure (PPEM): Reliability and validity in child and adolescent community mental health services. Administration & Policy in Mental Health & Mental Health Services Research. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10488-015-0698-x. Advance publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haine-Schlagel R, Walsh N. Parent participation engagement in youth and family mental health treatment. Clinical Child & Family Psychology Review. 2015;18(1):133–150. doi: 10.1007/s10567-015-0182-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M, Meaden A, Smith J, Jones C. Brief report: The development and psychometric properties of an observer-rated measure of engagement with mental health services. Journal of Mental Health. 2001;10(4):457–465. doi: 10.1080/09638230124439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood KE, Jensen PS, Acri MC, Olin SS, Lewandowski E, Herman RJ. Outcome domains in child mental health research since 1996: Have they changed and why does it matter? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(12):1241–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungbluth NJ, Shirk SR. Promoting homework adherence in cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42(4):545–553. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.743105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman WEK, Greener JM, Simpson DD. Assesing organizational readiness for change. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22(4):197–209. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(02)00233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Stoewe J, McCadam K, Gonzales J. Increasing access to child mental health services for urban children and their caretakers. Health & Social Work. 1998;23(1):9–15. doi: 10.1093/hsw/23.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray K, Woodruff K, Moon C, Finney C. Using text messaging to improve attendance and completion in a parent training program. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 2015;24(10):3107–3116. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0115-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem E, Gleacher A, Beidas R. Consultation as an implementation strategy for evidence-based practices across multiple contexts: Unpacking the black box. Administration & Policy in Mental Health & Mental Health Services Research. 2013;40(6):439–450. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0502-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Kazdin AE. Randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for increasing participation in Parent Management Training. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(5):872–879. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olin S, Hoagwood K, Rodriguez J, Ramos B, Burton G, Penn M, … Jensen PS. The application of behavior change theory to family-based services: Improving parent empowerment in children’s mental health. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 2010;19(4):462–470. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9317-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo AJ, Alegría M, Sirkin JT. Increasing the engagement of Latinos in services through community-derived programs: The Right Question Project-Mental Health. Professional Psychology: Research & Practice. 2012;43(3):208–216. doi: 10.1037/a0027730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A, Southam-Gerow M, O’Connor MK, Allin RB. An analysis of stakeholder views on children’s mental health services. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43(6):862–876. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.873982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self-Brown S, Whitaker DJ. Parent-focused child maltreatment prevention: Improving assessment, intervention, and dissemination with technology. Child Maltreatment. 2008;13:400–416. doi: 10.1177/1077559508320059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadnick N, Haine-Schlagel R, Martinez JI. Identifying factors associated with observational assessment of parent participation in community-based child mental health services. Child & Youth Care Forum. doi: 10.1007/s10566-016-9356-z. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zima BT, Hurlburt MS, Knapp P, Ladd H, Tang L, Duan N, Wells KB. Quality of publicly-funded outpatient specialty mental health care for common childhood psychiatric disorders in California. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(2):130–144. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200502000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]