Abstract

Objectives

Bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis has been performed without cardiopulmonary bypass for some single-ventricle heart defects. Limited data are available for the outcomes of off-pump bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis in infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. The purpose of this study is to determine the early outcomes for stage II palliation of hypoplastic left heart syndrome without cardiopulmonary bypass.

Methods

This is a retrospective review of infants having surgical palliation of hypoplastic left heart syndrome from April 2003 to March 2010 at a single institution.

Results

Seventy-five infants had a modified Norwood procedure, 65 with a right ventricle–pulmonary artery conduit, 10 with an aortopulmonary shunt, 2 with atrioventricular valve repair, and 3 with extracorporeal life support. Sixty-eight patients had hypoplastic left heart syndrome or one of its variants, and 7 had other single-ventricle lesions. There were 2 stage I deaths. Stage I survival was 97% (95% confidence interval, 88%–99%). Another 5 infants succumbed in the interstage period. Of the 68 stage I and interstage survivors, 61 had bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomoses, 20 without cardiopulmonary bypass. Median age was 6 months (range, 4–13 months), and median weight was 6.1 kg (range, 5.2–9.0 kg). There were no conversions to cardiopulmonary bypass when off-pump bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis was attempted. There were no hospital deaths. Median ventilation duration was 10 hours (range, 6–18 hours), and length of stay was 5 days (range, 4–9 days). Follow-up was available on all infants at a median duration of 17 months (range, 3–43 months), with no unplanned reinterventions.

Conclusions

Bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis without the use of cardiopulmonary bypass can be performed safely and with low mortality for selected infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Midterm to long-term outcomes remain to be determined. (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;141:400–6)

Outcomes for staged palliation of hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) and its variants have improved significantly over the last few decades. The second stage is a critical juncture at which significant benefit is offered. Stage II palliation attenuates pulmonary overcirculation, reduces the risk of sudden cardiac death, and provides a more stable circulation for infants having undergone the Norwood procedure.1–3 A number of surgical approaches and strategies have been developed for second-stage palliation, including the bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis (BCPA) or hemi-Fontan operation. Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) is routinely used with each and can include cardioplegic cardiac arrest, deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, or both.

The off-pump BCPA was first reported by Lamberti and colleagues in 19904 and has been applied to single-ventricle lesions with antegrade pulmonary blood flow through a native or banded main pulmonary artery (PA) or a systemic–PA shunt contralateral to the side of the superior vena cava (SVC).5,6 Data regarding stage II palliation of HLHS without the use of CPB are limited.

Originally described by Norwood and recently popularized by Sano and others, the right ventricle (RV)–PA conduit as a modification of the Norwood procedure has achieved increased use.7–12 The advantages of the conduit include higher diastolic blood pressure, potentially improved coronary perfusion with lower volume loading, and lower myocardial oxygen demand. The number of postoperative interventions required to balance the pulmonary and systemic circulations might also be reduced when compared with the use of a systemic–PA shunt.7 A recent report of more than 500 infants undergoing the Norwood procedure who were randomly assigned to the modified Blalock–Taussig shunt (n = 275) or the RV–PA conduit (n = 274) at 15 North American centers showed that survival 12 months after randomization was higher with the RV–PA conduit than with the modified Blalock–Taussig shunt.13 Another potential advantage of the RV–PA conduit is that it can be used for antegrade blood flow during performance of the off-pump BCPA, thus maintaining adequate oxygenation and gas exchange, whereas the superior cavopulmonary anastomosis is performed with the assistance of a passive venous shunt.

Here we report our experience with BCPA without CPB in selected infants with HLHS who had an RV–PA conduit as a modification of the Norwood procedure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Population

The pediatric cardiac surgery database at the University of California, San Francisco, was queried for all neonates having a modified Norwood procedure for HLHS or one of its variants or other forms of single-ventricle lesions with obstruction to systemic blood flow from April 2003 to march 2010. This patient cohort was then tracked for stage I and interstage survival, progression to stage II palliation, and subsequent survival. Infants palliated with an RV–PA conduit modification of the Norwood procedure were candidates for BCPA without CPB if there was no need for concomitant atrioventricular (AV) valve repair for moderate-to-severe insufficiency or left PA reconstruction for any degree of stenosis.

Perioperative and outcome data were also collected for a control group of patients having BCPA with CPB. Infants who had associated procedures, such as AV valve repair, repair of aortic arch stenosis, repair of RV aneurysm, atrial septectomy, and repair of pulmonary veins, were not included in this selected group.

Echocardiographic Analysis and Cardiac Catheterization

Preoperative echocardiographic analysis was performed in all patients, with particular focus on qualitative assessment of ventricular function; AV valve function; aortic arch, PA, and pulmonary venous anatomy; and interatrial septal patency. Ventricular function was subjectively graded as good, fair, or poor, whereas AV valve regurgitation was graded as none– trace, mild, moderate, or severe. Infants who had moderate or greater AV valve regurgitation or PA stenoses were not candidates for BCPA without CPB.

All infants had preoperative cardiac catheterization to assess candidacy for second-stage palliation, evaluate hemodynamics, and determine any anatomic abnormalities. Data acquisition included PA, atrial, ventricular, and aortic/arch pressures. Systemic, PA, superior caval, left atrial, and pulmonary venous hemoglobin–oxygen saturations were also measured.

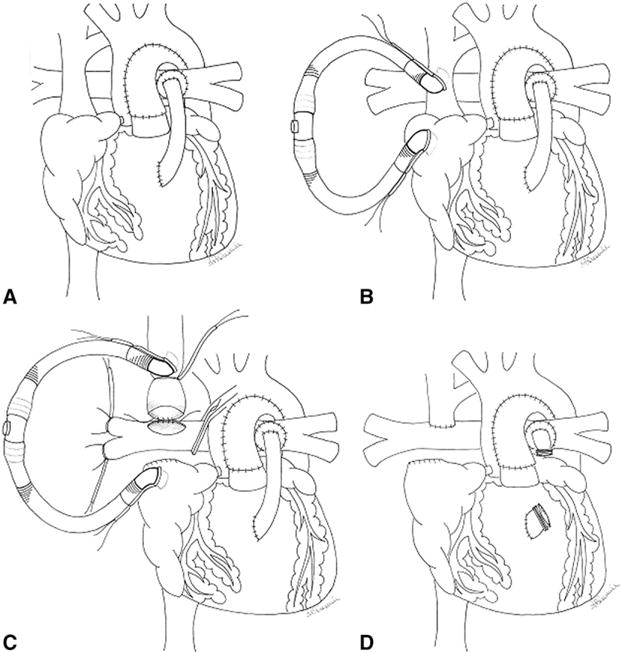

Operative Technique

After repeat sternotomy, dissection, and mobilization of all mediastinal and cardiac structures, a full dose of systemic heparin was given to achieve an activated clotting time of greater than 400 seconds. The right PA was extensively mobilized up to its hilar branches (Figure 1, A). A test occlusion of the right PA was then performed, and if hemoglobin–oxygen saturations remained greater than or equal to 70%, then the off-pump BCPA was performed. The SVC–innominate vein junction and right atrial appendage were cannulated with 12F Pacifico cannulas and were joined with a ¼-inch connector for insertion of a passive venous shunt (Figure 1, B). A snare was tightened above the azygous vein, which was doubly ligated. The SVC–right atrial junction was clamped and divided, and the cardiac end was oversewn with polypropylene sutures. After proximal and distal control of the right PA was achieved, a longitudinal arteriotomy was made. The end of the SVC was sewn to the PA with running fine polypropylene sutures (Figure 1, C). The anastomosis was deaired, the clamps and snares were removed, and the patient was decannulated. The RV–PA conduit was then dissected, mobilized, and quadruply clipped and divided (Figure 1, D). Protamine was administered, hemostasis was ensured, and bilateral pleural and single mediastinal drains were inserted. Chest drains were removed postoperatively when the total volume of drainage was less than 1 mL·kg−1·d−1. Continuous monitoring of arterial blood pressure, pulse oximetry, hemoglobin-oxygen saturation, and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) was performed perioperatively.

FIGURE 1.

Operative technique. See text for details.

Assessment of Outcomes

Outcomes measured included demographic information, morphologic data, intraoperative NIRS data, duration of ventilatory support, intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay, chest tube drainage, hospital length of stay, death, stroke, bleeding, infection, and postoperative hemoglobin– oxygen saturation at various time points (1 hour postoperatively, 6 hours postoperatively, 24 hours postoperatively, and before discharge) were collected.

Cerebral Monitoring and Neurologic Testing

NIRS was performed in all patients by using standard techniques, as previously reported.14,15 The Bayley Scales of Infant Development-II (BSID-II) was performed at 1 year. The mental development index and psychomotor development index scores are reported as means ± standard deviations. Comparisons of outcomes were performed by means of non-parametric testing with the Mann–Whitney test, assuming that normality or equality of variance is not met by either group.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as frequencies, means ± standard deviations or medians with appropriate ranges. Comparative statistical analysis between groups was performed by using t tests, Fisher exact tests, or Mann–Whitney tests, where appropriate. The study was reviewed and approved by the Committee on Human Research of the University of California, San Francisco, and need for patient consent was waived because of its retrospective nature.

RESULTS

Patients’ Characteristics

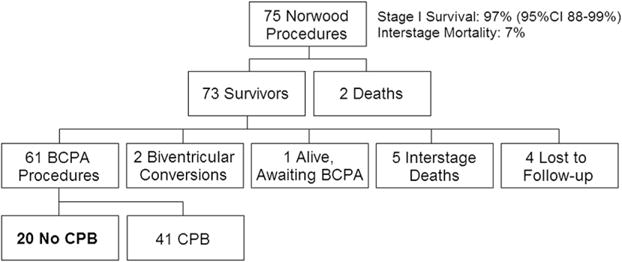

Figure 2 shows a flow diagram of the cohort of patients having undergone a Norwood procedure and the subsequent study population palliated with BCPA without CPB. Seventy-five infants had a modified Norwood procedure, 65 with an RV–PA conduit and 10 with a systemic–PA shunt. Two had associated AV valve repair, and 3 required extracorporeal life support postoperatively for cardiac arrest. Morphologic diagnoses included HLHS or one of its variants in 68 patients, and 7 patients had other single-ventricle lesions with arch/systemic obstruction (AV canal defect, n = 5; double-inlet left ventricle, n = 2). There were 2 stage I deaths, for a survival of 97% (95% confidence interval, 88%–99%). Another 5 infants died in the interstage period, for an interstage mortality of 7%. BCPA was performed in 61 infants, 20 of whom did not have CPB and are the subjects of this study.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram of the cohort of patients having undergone a Norwood procedure and the subsequent study population of patients who were palliated with bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis (BCPA) without cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) from April 2003 to March 2010. CI, Confidence interval.

The median age at second-stage surgical intervention was 6 months (range, 4–13 months), and the median weight was 6.1 kg (range, 5.2–9 kg). All patients had HLHS or one of its variants: aortic atresia and mitral atresia (n = 8), aortic atresia and mitral stenosis (n = 6), or aortic stenosis and mitral stenosis (n = 6).

Preoperative Data

Preoperative echocardiographic and cardiac catheterization data are summarized in Table 1. Qualitatively good RV function was present in 17 patients, and fair RV function was present in 3 patients. AV valve regurgitation was graded as none in 4, trace in 6, and mild in 10 patients. Median preoperative PA pressure was 14 mm Hg (range, 11–20 mm Hg), RV end-diastolic pressure was 8 mm Hg (range, 4–12 mm Hg), the calculated ratio of pulmonary–systemic blood flow was 1.3 (range, 0.7–1.9), calculated pulmonary vascular resistance was 2.3 Wood units (range, 1.1–3.5 Wood units), and median transpulmonary gradient was 5 mm Hg (range, 2–8 mm Hg).

TABLE 1.

Demographic, diagnostic, and preoperative echocardiographic and cardiac catheterization data for patients having bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis with and without cardiopulmonary bypass

| Preoperative data | Off-CPB group (n=20) |

On-CPB group (n=25) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic, median (range) | |||

| Age (mo) | 6 (4–13) | 5 (3–12) | .576 |

| Weight (kg) | 6.1 (5.2–9.0) | 6.2 (4.4–10.0) | .225 |

| Diagnostic, n (%) | |||

| Diagnoses | |||

| Aortic atresia, mitral atresia | 8 (40) | 10 (40) | 1.000 |

| Aortic atresia, mitral stenosis | 6 (30) | 8 (32) | .885 |

| Aortic stenosis, mitral stenosis | 6 (30) | 7 (28) | .883 |

| Echocardiography, n (%) | |||

| RV function | |||

| Good | 17 (85) | 12 (48) | .010 |

| Fair | 3 (15) | 7 (28) | .297 |

| Poor | 0 (0) | 6 (24) | .019 |

| AV valve regurgitation | |||

| None–trace | 10 (50) | 6 (24) | .070 |

| Mild–mild to moderate | 10 (50) | 15 (60) | .502 |

| Moderate–severe | 0 (0) | 4 (16) | .061 |

| Cardiac catheterization, median (range) | |||

| PA pressure (mm Hg) | 14 (11–20) | 15 (10–21) | .455 |

| RV end-diastolic pressure (mm Hg) | 8 (4–12) | 9 (5–14) | .264 |

| SVC saturation (%) | 49 (40–58) | 52 (40–58) | .729 |

| PA saturation (%) | 76 (64–83) | 79 (72–87) | .696 |

| Aortic saturation (%) | 76 (65–92) | 80 (72–84) | .630 |

| Left atrial saturation (%) | 97 (93–100) | 97 (81–99) | .126 |

| Ratio of pulmonary to systemic blood flow | 1.3 (0.7–1.9) | 1.6 (0.5–2.0) | 1.000 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (Wood units) | 2.3 (1.1–3.5) | 2.2 (1.2–2.9) | .925 |

| Transpulmonary gradient (mm Hg) | 5 (2–8) | 6 (3–9) | .740 |

CPB, Cardiopulmonary bypass; RV, right ventricular; AV, atrioventricular; PA, pulmonary artery; SVC, superior vena caval.

Operative Details

There were no intraoperative complications; systemic arterial desaturation of less than 70% or hemodynamic instability was not observed. Twelve (60%) patients required no intraoperative blood products. All patients had venous shunting for a median duration of 11 minutes (range, 8–18 minutes).

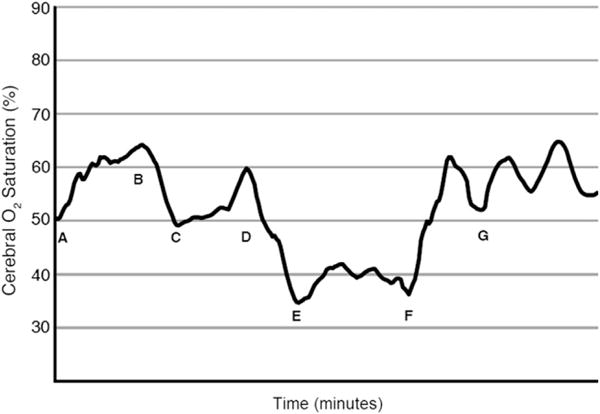

NIRS oximetric data were continuously recorded, and a representative tracing of cerebral oxygenation is shown in Figure 3. After induction of general anesthesia, endotracheal intubation, and ventilation with a fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) of 0.25, baseline NIRS cerebral oxygen saturation is 50%. The corresponding hemoglobin–oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry is 85% to 90%. The FIO2 is increased to 1, and the NIRS cerebral oxygen saturation increases to 65%. The right PA is controlled, the SVC is snared, and the upper body venous blood is returned to the right atrium through a venous shunt. At this point, the NIRS cerebral oxygen saturation decreases to 50% associated with a decrease in pulse oximetric hemoglobin–oxygen saturation to 70% to 75%. On completion of the anastomosis, the right PA clamp and hilar snares are released, and the venous shunt is removed. There is an associated increase in pulmonary blood flow (flow from the RV–PA conduit and BCPA). The systemic arterial oxygen saturation increases to 85%, and the NIRS cerebral oxygen saturation increases to 60%. In the subsequent phase of the operation, the heart is retracted rightward as the RV–PA conduit is being dissected and mobilized. There is an associated decrease in NIRS cerebral oxygen saturation. Once the RV–PA conduit is ligated and divided and cardiac retraction ceases, the NIRS cerebral oxygen saturation increases to greater than 60%.

FIGURE 3.

Intraoperative near-infrared spectroscopy as an indicator of cerebral oxygenation during off-pump bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis. A, Baseline near-infrared spectroscopic oximetry in an infant with hypoplastic left heart syndrome who had a right ventricle–pulmonary artery conduit modification of the Norwood procedure. The procedure was performed after achievement of general anesthesia for stage II palliation. B, The fraction of inspired oxygen is increased to 1, and cerebral oxygen saturation increases from 50% to 65%. C, The right pulmonary artery is controlled, and the superior vena caval–right atrial venous shunt is inserted. The superior vena cava is snared. The cerebral oxygen saturation decreases to 50%. D, The bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis is complete, and the caval snares and right pulmonary artery clamps are released. The cerebral oxygen saturation increases to 60%. E, The single right ventricle is retracted, and the right ventricle–pulmonary artery conduit is dissected, encircled, and ligated and divided. F, The cardiac retraction is terminated. G, The bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis with division of the right ventricle–pulmonary artery conduit is complete.

Postoperative Outcomes for BCPA Without CPB

Operative and hospital survival were both 100%. Median duration of ventilatory support was 10 hours (range, 6–18 hours). Median duration of ICU length of stay was 1 day (range, 1–4 days). Median time to chest tube removal was 4 days (range, 3–6 days). Median hospital length of stay was 5 days (range, 4–9 days). Follow-up was available in all 20 patients for a median duration of 17 months (range, 3–43 months) with no subsequent interventions. There were 2 late deaths, both at 11 months after discharge from stage II palliation. One occurred during urologic surgery and the other after a gastrointestinal surgical procedure. Postoperative outcomes are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Postoperative outcomes for patients having bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis with and without cardiopulmonary bypass

| Postoperative data | Off-CPB group (n=20) |

On-CPB group (n=25) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complication, n (%) | |||

| Bleeding | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Infection | 0 (0) | 2 (7.4) | 0.303 |

| Central Nervous System | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Injury/Stroke | |||

| Death | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Late mortality | 2 (10.0) | 5 (18.5) | .311 |

| Unplanned reinterventions | 0 (0) | 5 (18.5) | .043 |

| Hospitalization, median (range) | |||

| Hemoglobin–oxygen saturation (%) | |||

| 1 h Postoperatively | 88 (68–95) | 83 (67–91) | .041 |

| 6 h Postoperatively | 83 (77–91) | 82 (65–86) | .214 |

| 24 h Postoperatively | 85 (80–92) | 82 (75–84) | .006 |

| Discharge | 84 (74–97) | 80 (70–89) | .143 |

| Ventilation duration (h) | 10 (6–18) | 12 (4–108) | .066 |

| ICU length of stay (d) | 1.7 (1–4) | 5 (2–7) | .082 |

| Chest tube removal (d) | 4 (3–6) | 5 (3–12) | .056 |

| Hospital length of stay (d) | 5 (4–9) | 10 (6–29) | .001 |

CPB, Cardiopulmonary bypass; ICU, intensive care unit.

Comparison of Outcomes

Infants having undergone BCPA without CPB (n = 20) were compared with a select control group having undergone second-stage palliation with CPB (n = 25). Both groups were similar with respect to preoperative demographic and diagnostic data (Table 1). Infants in the on-CPB group were more likely to subjectively have more AV valve insufficiency (P = .061) or worse ventricular function (P = .019). Preoperative catheterization data suggested that both groups had similar hemodynamics, including PA pressures, transpulmonary gradients, and calculated pulmonary vascular resistances. Sixty percent of infants in the on-CPB group had associated pulmonary arterioplasty (Table 3). All infants in the on-CPB group were exposed to blood products at the time of surgical intervention compared with only 40% in the off-CPB group (P < .001, Table 3). Compared with the on-CPB group, infants in the off-CPB group had significantly higher postoperative hemoglobin–oxygen saturations at 1 and 24 hours after surgical intervention, but this difference narrowed at the time of discharge. Furthermore, infants in the off-CPB group had significantly shorter hospital length of stay; there was a trend toward statistical significance in terms of shorter duration of ventilatory support, shorter ICU length of stay, and earlier chest tube removal in the off-pump group. One-year neurologic testing by means of the BSID-II (Table 4) in selected patients in each group showed that the mental development index and psychomotor development index were higher in the off-CPB group. The highest scores were obtained by infants who had off-pump BCPA. The differences in mental development index and psychomotor development index scores, however, were not statistically significant.

TABLE 3.

Operative data for patients having bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis with and without cardiopulmonary bypass

| Operative data | Off-CPB group (n=20) |

On-CPB group (n=25) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Associated procedure, pulmonary arterioplasty, n (%) | 0 (0) | 15 (60) | .001 |

| Blood transfusion, n (%) | 8 (40) | 25 (100) | .001 |

CPB, Cardiopulmonary bypass.

TABLE 4.

Assessment of neurologic outcomes by Bayley Scales of Infant Development scores at 1 year postoperatively for infants having bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis with and without cardiopulmonary bypass

| Bayley Scales parameter | On-CPB group (n = 4) |

Off-CPB group (n = 3) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental development index (mean ± SD). | 66.5 ± 12.3 | 77.3 ± 8.5 | .15 |

| Psychomotor development index (mean ± SD) | 61.5 ± 9.5 | 74.0 ± 13.2 | .16 |

CPB, Cardiopulmonary bypass; SD, standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

Stage II palliation of HLHS after the modified Norwood procedure has conventionally included the use of CPB, deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, or both to complete a superior cavopulmonary anastomosis or hemi-Fontan operation.1 In the current study we report the completion of the BCPA without the use of CPB after a modified Norwood procedure (Sano modification). The BCPA provides a stable growing source of pulmonary blood flow in infants who have survived the Norwood procedure. Pulmonary overcirculation is eliminated, and the systemic RV is unloaded. This allows for potential improvements in RV geometry, tricuspid valve function, and improved efficiency of oxygenation for a given cardiac output. The approach is feasible, safe, and effective and has not required any conversions to CPB once initiated.

By avoiding CPB, this approach theoretically minimizes the complications associated with bypass. The inflammatory response might be attenuated, as are the effects of CPB on myocardial, renal, and pulmonary function. Furthermore, platelet depletion and dysfunction and activation of the complement and coagulation cascades might be reduced. The need for blood product transfusion and its associated complications can be markedly reduced. In the current series 60% of infants did not receive blood products, potentially reducing lung injury and optimizing BCPA flow dynamics.

The performance of the off-pump BCPA was first reported by Lamberti and colleagues4 and subsequently used by Murthy and associates,6 Luo and coworkers,5 and other groups. In most cases the technique was applied to children greater than 1 year of age and included those with bilateral SVC having bilateral BCPA. There are very few reports on the use of off-pump BCPA in the staged palliation of HLHS. Reinhartz and colleagues10 have referred to completion of the second stage in a recent report on the use of a valved RV–PA homograft conduit as a modification to the Norwood procedure. In that series 64% of BCPA procedures could be performed without CPB. Limited data on outcomes and associated factors were reported for this subgroup of patients. In our experience a smaller percentage of patients with HLHS having stage II palliation had off-pump BCPA after the Norwood procedure (20/61 [33%]). However, in the last 3 years, that percentage has increased to 58%.

Levi and colleagues16 also refer to 8 patients with HLHS in their series who had a Sano modification of the stage I Norwood procedure followed by an off-pump approach to the BCPA. Limited data, however, are provided regarding the specific outcomes and associated factors for this small group of patients.

We have not reported the data comparing the off-CPB group (n = 20) with the entire cohort of on-CPB infants (n = 41). The group comprising all infants having BCPA with CPB clearly had a significantly higher incidence of worse RV function and worse AV valve regurgitation. Furthermore, infants in the on-CPB group were younger and had higher RV end-diastolic pressures. They were more likely to require associated procedures, such as AV valve repair, atrial septectomy, RV outflow tract repair, pulmonary vein repair, or arch intervention. The on-CPB group had longer durations of ventilatory support and longer ICU and hospital lengths of stay. A comparison between this cohort and the off-CPB group would clearly favor the off-CPB group in terms of the condition of the patient and outcomes and challenge the validity of such a comparison. Therefore a selected group of infants undergoing BCPA with CPB (n = 25) were used for the comparison. There was still a trend, however, toward more favorable outcomes in the off-CPB group, including shorter ventilation requirements, shorter ICU length of stay, and earlier chest tube removal. Compared with the off-CPB BCPA group, the selected on-CPB group had a significantly longer hospitalization. Although the validity of such a comparison can still be questioned because of the inherent selection bias, one can conclude that off-pump BCPA might not be worse than the on-pump approach and might have some advantages in terms of resource use.

The use of the RV–PA conduit has gained increasing interest during stage I palliation of HLHS. The recent large, multi-institutional randomized trial comparing the RV–PA conduit with modified Blalock–Taussig shunt showed better transplantation-free survival at 1 year, as well as a lower incidence of serious adverse events during the Norwood hospitalization in the RV–PA group.13 Furthermore, RV size, function, and geometry are better with an RV–PA conduit compared with a Blalock–Taussig shunt within the first year after the Norwood procedure.13 We have found numerous advantages for the RV–PA conduit. First, we believe that it allows for advantageous postoperative hemodynamics, the diastolic blood pressure is relatively higher, and the myocardial oxygen supply/demand ratio is favorable. Fewer interventions to balance the systemic and pulmonary circulations are required in the early postoperative period.7 In our experience the stage I survival of 75 patients undergoing a modified Norwood procedure exceeds 95%. Interstage mortality might be improved.12 Mortality between stage I and stage II was 7% and similar to that reported by others who favor the RV–PA conduit.10 The RV–PA conduit offers another potential advantage in that it facilitates stage II palliation of HLHS without the use of CPB. Other strategies during stage I palliation, such as placement of a systemic–PA shunt on the left or central PA segment, might also allow for performance of the off-pump BCPA.

The use of passive venous shunting during the off-pump BCPA has generally been considered safe. On insertion of a passive venous shunt and SVC occlusion, the NIRS cerebral oxygen saturation decreased from 65% to approximately 50%. The decrease is associated with a decrease in systemic arterial hemoglobin–oxygen saturation as measured on pulse oximetry and is not unexpected because the right PA is occluded. The decrease in pulmonary blood flow might be associated with an increase in systemic output, but both the systemic arterial and cerebral NIRS oxygen saturation still decrease. Another potential reason for the decrease in cerebral oxygenation might be that the SVC pressure increases and causes a decrease in cerebral perfusion pressure, but SVC pressure was not measured. Murthy and associates6 reported an increase in the mean systemic venous pressure to approximately 20 mm Hg but considered this increase safe based on the good neurologic outcomes in their patient study group. NIRS oximetry shows a second decrease in cerebral oxygen saturation during the subsequent phase of the operation after completion of the BCPA, when the heart is being retracted rightward as the RV–PA conduit is being dissected. The manipulation and compression of the RV might cause a decrease in cardiac output, explaining the decrease in cerebral oxygen saturation measured by means of NIRS. Finally, cessation of RV manipulation and retraction and ligation of the RV–PA conduit is associated with an increase in cerebral oxygenation, as measured by means of NIRS, despite a reduction in pulmonary blood flow. This might be due to an increase in systemic output and improved efficiency of oxygenation.

A number of factors and events can influence the neurologic status and outcomes of children undergoing staged palliation of HLHS. These factors include prenatal diagnosis, proximity to a cardiac center, hypoxemic or hypotensive events after birth, intraoperative management during the Norwood procedure, presence of genetic syndromes or chromosomal anomalies, postoperative ICU course, presence and frequency of hypotensive or hypoxemic episodes, duration of circulatory arrest, interstage events, and development of intercurrent illnesses. Therefore a comparison of outcomes based on neurologic testing in infants undergoing BCPA with or without CPB would not necessarily be able to assign differences in neurologic outcome based solely on whether the BCPA was done on or off pump. It would be difficult to interpret the data because we could not necessarily control for the numerous factors that affect neurologic outcome, particularly with a small sample size. Hence comparing the outcomes of BSID-II testing between the on-CPB and off-CPB groups could not assign any differences or lack thereof to whether the second stage was done without CPB. Based on the NIRS and BSID-II data, there is no evidence to suggest, however, that BCPA done without CPB has harmful effects compared with BCPA done with CPB.

The limitations of this report include its retrospective observational nature and relatively small numbers. Although NIRS was used to monitor cerebral oxygenation and did not show any deleterious trends, direct measurements of SVC pressure and estimation of cerebral perfusion pressure were not made. The potential beneficial effects on inflammation and coagulation were not directly measured or examined and might be future areas of interest.

Second-stage palliation of HLHS without CPB appears to be a safe option. As with the second stage, a small number of patients can have the Fontan procedure without the use of CPB. Thus after the stage I Norwood procedure, it is possible for children with HLHS to have the subsequent 2-staged cavopulmonary connections completed without CPB, cardioplegic cardiac arrest, or deep hypothermic circulatory arrest.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AV

atrioventricular

- BCPA

bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis

- BSID-II

Bayley Scales of Infant Development-II

- CPB

cardiopulmonary bypass

- HLHS

hypoplastic left heart syndrome

- ICU

intensive care unit

- NIRS

near-infrared spectroscopy

- PA

pulmonary artery

- RV

right ventricle

- SVC

superior vena cava

Footnotes

Disclosures: Authors have nothing to disclose with regard to commercial support.

Read at the 36th Annual Meeting of The Western Thoracic Surgical Association, Ojai, Calif, June 23–26, 2010.

References

- 1.Karl TR. The bidirectional cavopulmonary shunt for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2001;4:58–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaquiss RD, Ghanayem NS, Hoffman GM, Fedderly RT, Cava JR, Mussatto KA, et al. Early cavopulmonary anastomosis in very young infants after the Norwood procedure: impact on oxygenation, resource utilization, and mortality. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:982–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheurer MA, Hill EG, Vasuki N, Maurer S, Graham EM, Bandisode V, et al. Survival after bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis: analysis of preoperative risk factors. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134:82–9. e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamberti JJ, Spicer RL, Waldman JD, Grehl TM, Thomson D, George L, et al. The bidirectional cavopulmonary shunt. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1990;100:22–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo XJ, Yan J, Wu QY, Yang KM, Xu JP, Liu YL. Clinical application of bidirectional Glenn shunt with off-pump technique. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2004;12:103–6. doi: 10.1177/021849230401200204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murthy KS, Coelho R, Naik SK, Punnoose A, Thomas W, Cherian KM. Novel techniques of bidirectional Glenn shunt without cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:1771–4. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azakie A, Martinez D, Sapru A, Fineman J, Teitel D, Karl TR. Impact of right ventricle to pulmonary artery conduit on outcome of the modified Norwood procedure. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1727–33. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norwood WI, Lang P, Hansen DD. Physiologic repair of aortic atresia-hypoplastic left heart syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:23–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198301063080106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sano S, Ishino K, Kawada M, Arai S, Kasahara S, Asai T, et al. Right ventricle-pulmonary artery shunt in first-stage palliation of hypoplastic left heart syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:504–10. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(02)73575-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reinhartz O, Reddy VM, Petrossian E, MacDonald M, Lamberti JJ, Roth SJ, et al. Homograft valved right ventricle to pulmonary artery conduit as a modification of the Norwood procedure. Circulation. 2006;114(suppl):I594–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.001438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghanayem NS, Jaquiss RD, Cava JR, Frommelt PC, Mussatto KA, Hoffman GM, et al. Right ventricle-to-pulmonary artery conduit versus Blalock-Taussig shunt: a hemodynamic comparison. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1603–10. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.05.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pizarro C, Mroczek T, Malec E, Norwood WI. Right ventricle to pulmonary artery conduit reduces interim mortality after stage 1 Norwood for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1959–64. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohye RG, Sleeper LA, Mahony L, Newburger JW, Pearson GD, Lu M, et al. Comparison of shunt types in the Norwood procedure for single-ventricle lesions. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1980–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azakie A, Muse J, Gardner M, Skidmore KL, Miller SP, Karl TR, et al. Cerebral oxygen balance is impaired during repair of aortic coarctation in infants and children. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:830–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McQuillen PS, Nishimoto MS, Bottrell CL, Fineman LD, Hamrick SE, Glidden DV, et al. Regional and central venous oxygen saturation monitoring following pediatric cardiac surgery: concordance and association with clinical variables. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8:154–60. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000257101.37171.BE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levi DS, Scott V, Bryan T, Plunkett M. Preferential use of “off pump” Glenn shunts: a single-center experience. Congenit Heart Dis. 2009;4:81–5. [Google Scholar]