Abstract

Statins have become a cornerstone of risk modification for ischaemic heart disease patients. A number of studies have shown that they are effective and safe. However studies have observed an early benefit in terms of a reduction in recurrent infarct and or death after a myocardial infarction, prior to any significant change in lipid profile. Therefore, pleiotropic mechanisms, other than lowering lipid profile alone, must account for this effect. One such proposed pleiotropic mechanism is the ability of statins to augment both number and function of endothelial progenitor cells. The ability to augment repair and maintenance of a functioning endothelium may have profound beneficial effect on vascular repair and potentially a positive impact on clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. The following literature review will discuss issues surrounding endothelial progenitor cell (EPC) identification, role in vascular repair, factors affecting EPC numbers, the role of statins in current medical practice and their effects on EPC number.

Keywords: Statins, Endothelial progenitor cells, Pleiotropic effects, Ischaemic heart disease, Pleiotropic mechanisms

Core tip: Statin therapy is a cornerstone of current management in coronary artery disease. Conventional thinking of stain therapy is for reduction of low-density lipoproteins. However a number of studies have observed an early benefit prior to any significant change in lipid profile. Therefore alternative pleiotropic mechanisms to account for this have been proposed. One such proposed mechanism is the ability of statins to augment both number and function of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs). The following literature review discusses issues surrounding EPC identification, role in vascular repair, the role of statins in current medical practice and their effects on EPCs.

INTRODUCTION

The maintenance of endothelial integrity is essential for the preservation of a healthy vasculature[1]. This integrity results from a balance between on-going endothelial damage and the rate of vascular repair. Disruption of endothelial integrity or impairment of endothelial repair mechanisms is a central step in both the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis[2]. Endothelial repair is dependent on undifferentiated cells migrating to sites of vascular injury[3-5] then differentiating into mature endothelial cells[6-13]. These undifferentiated cells are called endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) have a central role in vascular repair by virtue of their ability to proliferate, migrate to site of vascular injury and then differentiate into mature vascular endothelium[13,14]. EPCs perpetuate this cycle by secreting pro-angiogenic cytokines[15].

Statins form the corner stone of treatment of coronary artery disease. The safety and efficacy of statins in reducing cardiac events by decreasing serum LDL-cholesterol has been well described[16-18]. Recently however studies have shown the early beneficial effect of statins occurs before any significant change in lipid profile. This led to the hypothesis that cardiovascular benefits of statins may occur via alternative mechanisms other than reduction of LDL-cholesterol alone[19,20]. One such proposed mechanism is the ability of statins to augment both number and function of EPCs.

The following literature review discusses issues surrounding EPC identification, role in vascular repair, factors affecting EPC numbers, the role of statins in current medical practice and their effects on EPC number.

RESEARCH AND LITERATURE

We performed a review of various studies within the literature available on endothelial progenitor cell and statins. The authors searched various databases (EMBASE, OVID, PubMed) using the keywords: “Endothelial progenitor cells”, “statin”, “pleiotropic effects”. We studied the various publications that we obtained from the search results. Full text manuscripts were obtained. We only included papers in the English language.

EPCS

Cellular identification and staging of differentiation has been made possible by specific surface receptors called epitopes that allow immunophenotyping. This process allows identification of subset of cellular surface molecule termed cluster of differentiation (CD). Cellular subtypes may be defined by the presence or absence of a particular CD molecule. Therefore “CD” may be “+ “or “-” denoting either presence or absence of a particular CD, and is used to describe stem cells rather than fully differentiated cell types. Certain cell types may have variable CD marker expression during maturation for example, and therefore classed as bright (high), mid (mid) or dim (low) denoting intensity of expression[21,22].

Vascular repair had previously been thought to be due to migration and proliferation of fully differentiated endothelial cells, in a process called angiogenesis[23]. Asahara et al[24] identified putative cells with cell surface marker CD34+, alternately named kinase insert domain receptor (KDR/VEGFR) markers capable of differentiating into endothelial cells both in vitro and in vivo[24-26]. Subsequent studies recognised that in fact undifferentiated cells subsequently termed EPCs migrated to sites of neovascularization and then differentiate into endothelial cells[24,26] in a process called vasculogenesis[27]. EPCs are derived from pluripotential stem cells within the bone marrow. These then evolve into mature endothelial cells[24] accounting for only 0.001%-0.0001% of peripheral blood cells in an unstressed state[28]. Circulating EPCs may be isolated from bone marrow or the circulation as mononuclear cells[24,29,30], expressing a variety of endothelial surface markers[31]. However, there currently remains a lack of consensus on phenotypic and functional definition of endothelial precursor cells[32,33].

EPCs are a diverse group of cells of different lineages that have angiogenic potential, but are not always necessarily able to differentiate into functional endothelial cells as would be suggested from their name[32]. EPCs are derived from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells[6,24,29,31], with the subset of EPCs characterized by co-expression of endothelial marker proteins[6,29,31]. Studies have identified 3 markers associated with early functional EPCs including CD133, CD34, and the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) also known as kinase insert domain receptor (KDR, Flk-1 or CD309)[7,31]. Therefore EPCs express markers of both hematopoietic stem cells (CD34 and CD133) and endothelial cells (CD146, vWF, and VEGFR2)[26,28,29,31,34-37]. The presence of certain cell surface markers are depend on the stage of maturations of the EPC. For example the cell surface marker CD133, a 120-kDa trans-membrane polypeptide, is expressed on bone marrow derived hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in peripheral blood[37]. The expression of CD133 on EPCs declines during maturation within the peripheral circulation. Currently there remains some uncertainty as to when EPCs lose the CD133 surface marker, whether during transmigration from bone marrow to circulation or later whilst in the peripheral blood system[38]. Nevertheless the loss of CD133 represents the transformation into more mature EPCs that are endothelial-like cells[37]. Whereas the expression of CD34 a cell surface marker found on immature pluripotential stem cells[31] that acts as an adhesion molecule, although the precise function remains unclear, gradually increases as the CD133 decreases as the EPC matures[37]. During the course of maturity EPCs begin to have increased expression of other markers specific to endothelial cells such as VEGFR-2, VE-cadherin, and von Willebrand factor (vWF)[37].

The expression of CD34+, CD133+, and/or VEGF2+ has been used as identifying markers of EPCs in a number of studies[28,32,39-41]. Whereas as other studies advocate the use of CD133+ either alone or in combination with CD34+/VEGFR-2+ cells for identification of EPCs[31,42]. In contrast, other studies have suggested that CD133+ are haematopoietic cell lines and have not been identified in and therefore unable to form endothelial phenotypic EPCs[7,40,43]. Ingram et al[28] proposed that CD45- cells incorporated “true” circulating EPCs and verified by other studies[28,39,40,43]. Interestingly, CD34+/VEGFR2+ and diminished (dim) CD45 (CD45dim) cells have been found to have greater correlation with coronary heart disease severity and response to statin therapy[44,45].

In summary, the maturity of the EPC is marked by the gradual loss of CD133, gradual increased expression of CD34+ and the appearance of CD31, VE-cadherin and vWF cell surface markers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Table to show cell markers during development of endothelial progenitor cell

|

Endothelial progenitor cells |

|||

| Bone marrow |

Circulation |

||

| Early EPCs | Mature EPCs | ||

| CD133+ | + | +/- | - |

| CD34+ | + | + | + |

| VEGFR2+ | + | ++ | +++ |

| CD31+ | - | + | + |

| VE-cadherin | - | + | + |

| vWF | - | + | + |

EPC: Endothelial progenitor cell; VEGFR: Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

EPCS AND CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Endothelial integrity is essential for healthy vasculature, and can be thought of as a balance between continued endothelial damage and the capacity to repair by a pool of EPCs[9,46]. It is now generally accepted that cardiovascular risk correlates with EPC numbers. Highlighting the integral relationship between endothelium and atherosclerosis[47-51], disruption of endothelial integrity by endothelial cell injury has been shown to be a stimulus for the development of atherosclerosis[2], but also as a stimulus for augmentation of EPC number and function[9,52,53]. Continued endothelial damage[54] may lead to an eventual reduction of the number of EPCs. Elevated EPC numbers have been shown to be associated with augmented formation of collaterals in coronary artery disease[55] and restoration of endothelial vasodilator function[9]. A reduction in EPC numbers may lead to deficient endothelial repair and progression of atherosclerosis, with further EPC depletion and perpetuation of atherosclerosis[9,56]. However, it is uncertain whether low numbers of circulating EPCs represents enhanced usage by vascular repair processes, or reduced production by bone marrow.

CD34+ VEGFR2+ EPCs cells have been shown to be reduced in patients with atherosclerotic coronary and peripheral disease[57]. Vasa et al[56] found not only reduced numbers, but also impaired function of EPCs in patients with coronary artery disease. Elevated numbers of EPC have been associated with freedom from myocardial infarction, hospitalization, revascularization and cardiovascular death in patients with coronary artery disease[56,58]. Furthermore the predictive value of EPC count has been shown to be independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors[9,46,59]. In fact, the extent of the reduction in EPC numbers has been associated not only with coronary artery disease burden[60], but also the presence of symptoms[61,62].

Finally, elevated numbers of circulating CD34+/CD133+/VEGFR2 EPCs have been observed after an acute myocardial infarction[42,63]. This may be regarded as a consequence of cardiac ischaemia together with raised inflammatory and haematopoietic cytokines stimulating EPC mobilisation from the bone marrow[64-66]. A similar response is seen following coronary angioplasty[67], and interestingly, the combination of an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) treated by angioplasty provoked an enhanced EPC response[68]. Therefore, EPC may have a central role not only in repairing coronary vessels after plaque rupture, but also after any coronary intervention.

STATIN THERAPY

Statins act by competitively inhibiting 3 hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl Coenzyme A (HMG CoA) reductase, the rate limiting step in the mevalonate pathway producing isoprenoids including cholesterol. The competitive inhibition of HMG CoA reductase induces the expression of LDL receptors within the liver, thereby increasing the catabolism of plasma LDL, with a consequent decrease in LDL-cholesterol levels[69].

The safety and efficacy of statins in reducing cardiac events by decreasing serum LDL-cholesterol has been well described[16-18]. Statin therapy has been shown to reduce death and cardiovascular events in primary prevention of atherosclerosis[70], stable coronary artery disease[16,71-73], ACS[74,75] and secondary prevention[72]. Statins also appear to reduce development of atherosclerotic lesions[76,77] and decrease plaque burden[13,78].

The beneficial effect of intensive statin therapy was studied in a prospective meta-analysis of 90056 patients from 14 randomised trials and found greater cholesterol reduction was associated with better patient outcomes[19]. The study found that the 5-year incidence of major adverse cardiac events, coronary revascularization and stroke was reduced by one fifth for every millimoles per liter reduction in LDL cholesterol, which was irrespective of the initial lipid profile[19].

Another meta-analysis found aggressive statin therapy was associated with reduced peri-procedural myocardial infarction and a 44% risk reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events at 30-d irrespective of clinical presentation[79]. Moreover, the ARMYDA-RECAPTURE study[80] found reloading of the high dose statin, atorvastatin 80 mg in 383 NSTEMI and stable angina patients on chronic therapy prior to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) had a 50% reduction in 30-d major adverse cardiac events in both group with a greater reduction in NSTEMI group[80].

These studies led to the universal adoption of statin therapy in patients with coronary artery disease irrespective of presentation from stable angina to ACSs[81,82].

THE EFFECT OF STATIN THERAPY ON EPCS

Several studies have shown the early beneficial effect of statins occurs before any significant change in lipid profile. This led to the hypothesis that cardiovascular benefits of statins may occur via alternative mechanisms other than reduction of LDL-cholesterol alone[19,20]. These potential beneficial effect(s) may represent a potential therapeutic target for ischemic heart disease patients, and therefore is of great interest. There have been a number of mechanisms proposed to account for pleiotropic effects of statin therapy. These include reduction in vascular inflammation[83], reduction of platelet aggregability and thrombus deposition[77,84-86], enhancement of fibrinolysis[87] and increased endothelium derived NO production[88-90]. However the mechanism that has evoked the most interest is the impact of statins on EPCs[70].

Statin therapy has been associated with greater numbers of circulating EPCs by enhancing mobilization, differentiation, increasing longevity, enhance homing to sites of vascular injury with augmentation of re-endothelisation by enhancing expression of adhesion molecules on EPC cell surface membrane[3,70,91-94].

However, the duration of the effect on EPC number by statin therapy continues to remain contentious.

In one study, atorvastatin therapy was shown to significantly increase circulating EPC as soon as 1 wk with plateauing after 3-4 wk with a 3-fold increase of EPCs from baseline in a stable angina population was also observed[70]. Whereas Deschaseaux et al[95] investigated whether EPCs could be firstly detected and secondly characterized in patients receiving long-term statin therapy defined as 4 wk. The group found a significantly greater number of CD34+, CD34+/CD144+ circulating EPC in patients receiving statin therapy compared to statin naïve patients. Interestingly two types of EPCs were detected, early and late EPCs. The early EPCs were found to form elongated cells whereas the late EPC population gave rise to cobblestone-like colonies with strong proliferation capacities seen in-vitro cell culture. The numbers of early EPCs were significantly higher in patients not receiving statin therapy whereas late EPCs were significantly higher in patients receiving statin therapy. The study also observed that long term statin therapy specifically maintained late EPCs in circulation with a CD34+/CD144+ phenotype. Rodent studies have found rosuvastatin resulted in a greater than 3 fold increase in EPC numbers when compared with placebo as long as 10 wk after myocardial infarction[56]. Long-term atorvastatin 10 mg for 12 mo markedly increased EPC number with an associated decrease in oxidative DNA damage[35]. However to the contrary, Hristov et al[96] found reduced numbers of circulating EPCs in CHD patients on long-term statin treatment.

Statins appear to have a dose dependant effect on EPC count. A double blinded randomised pilot study found greater number of circulating CD34+ VEGFR-2+ EPCs after 12 wk of therapy with pravastatin 20 mg when compared to atorvastatin 10 mg[97]. Similarly, in ACS patients’ intensive statin therapy with atorvastatin 80 mg after primary or rescue PCI was associated with greater EPC count at 4-mo follow up as compared to 20 mg atorvastatin. The authors found no beneficial effect in an improvement of LV function[98]. Furthermore statin reloading in patients on moderate statin therapy undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention has been shown to increase EPC count[99,100] this correlates with the beneficial effect of statin reloading of high dose statin in patients on chronic therapy[80] mentioned above.

PLEIOTROPIC EFFECTS OF STATIN THERAPY

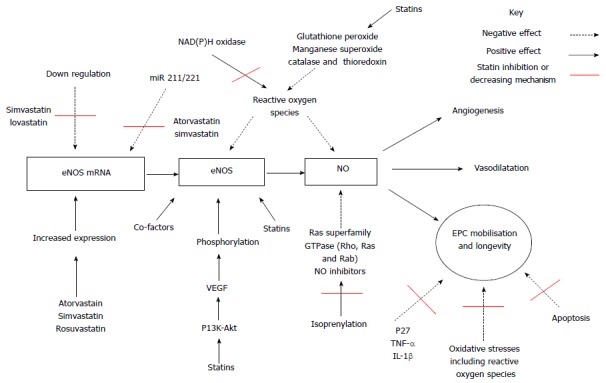

Several proposed intracellular signaling mechanisms accounting for the pleiotropic effect of statin therapy have been put forward. Figure 1 below summarizes the positive and negative effects on EPC proliferation, mobilisation and longevity but also the effect of statin therapy.

Figure 1.

Simplified diagram illustrating the positive and negative effects on endothelial progenitor cell proliferation, mobilisation and longevity together with proposed mechanisms of action of statin therapy. EPC: Endothelial progenitor cell; NO: Nitric oxide; eNOS: Endothelial nitric oxide synthase; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor; mRNA: Messenger ribonucleic acid; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL-1: Interleukin 1; P13k-AKT: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase - protein kinase B pathway; NAD(P)H oxidase: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-oxidase; miR : Micro non-coding ribonucleic acid.

Nitric oxide pathway

The first proposed intracellular signaling mechanisms involves nitric oxide pathway. The endothelium releases nitric oxide (NO), a primary mediator of smooth muscle tone that causes vasodilatation through the activity of endothelial-type nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)[101-104]. NO has an central role in vascular homeostasis with its bioavailability dependent on expression of endothelial eNOS[105], presence of eNOS substrate and or co-factors[106], phosphorylation of eNOS[107,108] or due to excessive depletion of NO such as seen with presence of excessive reactive oxygen species[109]. However the main functions of NO is as a cellular signaling molecule[101], an angiogenic factor involved in stimulation, promotion, and stabilization of new blood vessels together with VEGFs, FGFs, Angiopoietins, PDGF, MCP-1, TGF, various integrins, VE-cadherin[110-113]. Statin therapy has been proposed to both enhance expression and activity of eNOS[114] a prerequisite stage for statin-mediated EPC mobilisation[115]. Statins are known to augment eNOS activity[116-118], increase eNOS expression and restoration of endothelial function[104,119-121]. Statins have also been associated with increased EPC longevity via several pathways including inhibition of p27[122], down regulating TNF-α or IL-1β expression[123] and prolonging eNOS expression[122] and finally by increasing eNOS mRNA half-life[124,125]. Kosmidou et al[126] found simvastatin and rosuvastatin prolonged expression by increasing 3’ polyadenylation of eNOS mRNA. Laufs et al[88,124] firstly noted simvastatin and lovastatin reversed the down-regulation of eNOS expression caused by hypoxia and secondly simvastatin reversed down regulation of eNOS expression induced by oxidized LDL[88,124] a recognised cause of atherosclerosis.

miR 221 and miR 222 levels

A second observed pleotropic mechanism of statin therapy has been a decreased level of micro non-coding RNAs called miR 221 and miR 222. These negatively regulate protein expression at post-transcriptional stage[127]. This down regulating effect occurs by targeting 3’ untranslated regions resulting in either degradation of target mRNA or impairing translation[128]. Furthermore miR-221 and miR-222 have been observed to regulate proliferation and differentiation of CD34-positive haematopoietic progenitor cells by reducing expression of c-kit receptor factor impairs haematopoietic progenitor cell proliferation[129]. Increased miR-221 and or miR-221 expression in EPC down regulates EPC differentiation and mobilisation via c-kit and or eNOS pathways in coronary artery disease patients[127]. Atorvastatin has been shown firstly to decrease miR 221 and miR 222, and secondly increase EPC numbers[127]. Cerda et al[130] found both atorvastatin and simvastatin increased NO levels and NOS3 mRNA expression, whereas ezetimibe did not. Atorvastatin, simvastatin and ezetimibe have all been shown to down-regulate the expression of miR-221, whereas miR-222 was reduced only after atorvastatin treatment. The magnitude of the reduction of miR-221 and miR-222 after treatment with statins correlated with an increment in NOS3 mRNA levels[130]. The eNOS and miR221/222 are thought likely to be components of the same pathway[131].

The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway

The third proposed pleiotrophic mechanism involves the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway plays. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway plays a central role in multiple cellular processes, including cell proliferation, angiogenesis, metabolism, differentiation and longevity[132,133]. PI3K generates phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) an important lipid secondary messenger which in turn plays a central role in several signal transduction pathways[134,135] including activation of the serine/threonine kinases PDKl and Akt. Akt controls protein synthesis and cell growth via the phosphorylation of mTOR[136]. The PI3K/Akt pathway has been associated with angiogenesis through the regulation of the NO signaling pathway[137]. The PI3K pathway releases a group of angiogenic factors including VEGF. VEGFR2 has a central role in VEGF-induced angiogenesis[138]. VEGF is required for the migration of endothelial cells and via PI3K-Akt dependent manner allows formation of capillary like structures[139]. Studies have shown that NO production may be induced by VEGF and appears to be attenuated by the inhibition of PI3K[140]. This is thought to occur via phosphorylation of eNOS at the serine 1177 residue by Akt[107,141], required for the VEGF induced endothelial cell migration[142]. Factors that stimulate the PI3K/Akt protein kinase pathway, including statins, have been shown also to activate eNOS[87,141,143]. In turn, the expression of eNOS appears to be fundamental for mobilization of EPC and any impairment in PI3K/Akt/eNOS/NO signaling pathway may result in decreased EPC number[91,92].

The PI3K/Akt/mTOR intracellular pathway via inhibition of the Rho kinase has also been shown to preserves mitochondrial permeability transition pore preventing mitochondrial apoptosis, and therefore death, while conserving cardiomyocyte function[144,145].

These proposed mechanisms may account for difference in the effect of statin therapy in acute or chronic therapy. Statins given during acute ischaemic stress have been shown to firstly potentiate adenosine receptors[146,147] eventually leading to downstream regulation of eNOS and therefore increases NO production. Secondly statins augment activation of the reperfusion injury salvage kinase (RISK) pathway[148]. This results in enhanced activity of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR intracellular signal pathways[149], leading to preservation of mitochondrial function and cardio-protection. Short-term high dose statin therapy have shown an increase in both EPC mobilisation from bone marrow and augmented function[92,150-154].

Whereas chronic statin therapy has been linked to a phenomenon termed pre-ischaemic conditioning, protecting the myocardium against ischaemia[155]. This is believed to be secondary to statin induced NO availability by up regulation of eNOS and stabilisation of eNOS mRNA. Secondly, by increased production of NO and superoxide radicals improves vascular function and reducing vascular inflammation respectively[88,156]. Statins also inhibit isoprenylation of a number of Ras superfamily GTPase including Rho, Ras and Rab[157] NO inhibitors resulting in increased NO bioavailability. Thirdly, by preventing mitochondrial apoptosis and preservation of cardiomyocyte function via the up-regulation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR intracellular signalling pathway by inhibition of Rho kinase[144,145]. However, the RISK pathway has been shown the down regulated with chronic statin therapy[158] and has been shown to become reactivated by statin re-loading[159]. The latter may account for the increase in EPC count in patients on chronic statin therapy reloaded with statin therapy[80,99,100].

Oxidative stresses

Finally, EPC mobilisation and or function may also be affected by oxidative stress[153,160]. Oxidative stresses occur secondary to generation of oxygen free radicals or reactive oxygen species (ROS). Oxidative stress has a central role in cardiovascular disease, and a pivotal role in atherosclerosis[161]. Cellular oxidative stress seen with oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) has a central role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. LDL is oxidised by reactive oxygen species from both circulating cells and cells on vascular walls[162,163]. In essence, LDL oxidation is a result of a chain reaction of free radicals converting polyunsaturated fatty acids into lipid peroxides and as a consequence, formation of active aldehydes[164]. The biochemical reaction forming ox-LDL have been found to cause senescence of EPCs[165]. Whereas high density lipoprotein is regarded as atheroprotective due to some part of its antioxidant properties also has a positive effect on EPC number and function[166]. There are a number of endogenous antioxidants exerting protective effects by scavenging ROS. An indirect way ROS effects EPCs includes ROS reacting with NO forming a potent oxidant[167] with a consequent decrease in NO. Decrease in NO either by excessive oxidation or impaired production reduces EPC mobilisation and/or function[161,168]. Secondly, direct exposure to oxidative stresses or in disease conditions with high oxidative stress, for example diabetes, is associated with induced EPC apoptosis with significant reduction in EPC numbers[168,169], mobilisation, function[170] and reduced ability to migrate and or integrate into vasculature[161,171].

In an attempt to counteract the effects of oxidative stress EPCs produce superoxide dismutase[172]. Interestingly, cardiovascular risk factors have been found to alter and or reduce the EPC antioxidant ability. Healthy volunteers have found to express higher levels of antioxidative enzyme catalases including glutathione peroxidase and manganese superoxide dismutase when comparing patients with cardiovascular disease[173,174]. The underlying pathophysiological mechanism currently remains undetermined. The antioxidant pleiotropic effect of statins may include indirect mechanism increasing NO bioavailability accounting for antioxidant properties contributing to an increase in EPC mobilisation and or function[114,175]. Secondly statin therapy has also been shown to inhibit activation of NAD(P)H oxidase and ROS release[176] but also activate catalase and thioredoxin ROS scavenging mechanisms[176,177]. Finally, statins appear to have a direct effect by significantly reducing peroxide induced apoptosis of EPCs[169] and decreasing the oxidative damage to DNA in EPCs[178].

G proteins and G protein-coupled receptors

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) are comprised of seven trans-membrane domain proteins and are a super family consisting of a large and diverse number of proteins encoded by approximately 5% of human genes[179]. There have been a number of classification systems proposed the most recent “GRAFS” (Glutamate, Rhodopsin, Adhesion, Frizzled/Taste2 and Secretin)[180]. In mammals there are five main families[181]. GPCRs have an integral role in transfer of extracellular stimuli to within the cell by conformational changes in transmembrane domain structure[182-185]. They regulate physiological responses to a myriad of endogenous ligands including amines, glycoproteins, peptides and lipids. Therefore, not surprisingly that GPCRs have been implicated in regulation of cellular maintenance, differentiation, proliferation and migration of various stem cells[186-189].

GPCRs modulate activity of intracellular signaling via G proteins. There are currently four known G protein subfamilies each able to potentiate a number of drown stream effectors triggering a number of signaling pathways[182]. These include activation of Rho associated kinases[190,191], activation or inhibition of cyclic AMP production[192] and PI3Ks and therefore modulate the PI3K/Akt pathway[193,194]. The aforementioned have been implicated in EPC proliferation and function as described above. GPCRs have evoked great interest as a possible target for novel drug therapy[195] as an estimated 50% of all currently prescribed drugs target only a small proportion of GPCRs[196]. They are also becoming increasingly recognised as having a major role in stem cell signaling[197]. The role of GPCR in regulation and function of EPCs and the effect of statin therapy remains yet to be elucidated however current evidence suggests that they may have a pivotal role.

CONCLUSION

EPCs have a pivotal role in the maintenance of vascular integrity. However, factors that influence EPC number, migration and function are now becoming recognised and have potentially a significant role in management of ischaemic heart disease patients. Statins once thought to modify cardiovascular risk only by lowering LDL-cholesterol are now being acknowledged as having alternative mechanisms that appear to have beneficial pleiotropic effects. One such mechanism may be mediated by EPCs. A number of studies have shown positive pleiotropic effect of statins on EPCs, both function and number. There appears to be a complex interaction between statins and EPC that is only now becoming recognised. Despite great progress since Asahara’s pioneering work, there remain gaps within our knowledge regarding the pleiotropic effect(s) of statins on EPCs. Further studies are required to elucidate and fully understand any pleiotropic effect and this may guide future beneficial therapeutic interventions.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: Authors declare no conflict of interests for this article.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: June 24, 2016

First decision: August 11, 2016

Article in press: November 2, 2016

P- Reviewer: Das UN, Jiang B, Lymperopoulos A S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Dong C, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ. Endothelial progenitor cells: a promising therapeutic alternative for cardiovascular disease. J Interv Cardiol. 2007;20:93–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2007.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross R. Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walter DH, Rittig K, Bahlmann FH, Kirchmair R, Silver M, Murayama T, Nishimura H, Losordo DW, Asahara T, Isner JM. Statin therapy accelerates reendothelialization: a novel effect involving mobilization and incorporation of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells. Circulation. 2002;105:3017–3024. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000018166.84319.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griese DP, Ehsan A, Melo LG, Kong D, Zhang L, Mann MJ, Pratt RE, Mulligan RC, Dzau VJ. Isolation and transplantation of autologous circulating endothelial cells into denuded vessels and prosthetic grafts: implications for cell-based vascular therapy. Circulation. 2003;108:2710–2715. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000096490.16596.A6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujiyama S, Amano K, Uehira K, Yoshida M, Nishiwaki Y, Nozawa Y, Jin D, Takai S, Miyazaki M, Egashira K, et al. Bone marrow monocyte lineage cells adhere on injured endothelium in a monocyte chemoattractant protein-1-dependent manner and accelerate reendothelialization as endothelial progenitor cells. Circ Res. 2003;93:980–989. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000099245.08637.CE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhattacharya V, McSweeney PA, Shi Q, Bruno B, Ishida A, Nash R, Storb RF, Sauvage LR, Hammond WP, Wu MH. Enhanced endothelialization and microvessel formation in polyester grafts seeded with CD34(+) bone marrow cells. Blood. 2000;95:581–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gehling UM, Ergün S, Schumacher U, Wagener C, Pantel K, Otte M, Schuch G, Schafhausen P, Mende T, Kilic N, et al. In vitro differentiation of endothelial cells from AC133-positive progenitor cells. Blood. 2000;95:3106–3112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu Y, Davison F, Zhang Z, Xu Q. Endothelial replacement and angiogenesis in arteriosclerotic lesions of allografts are contributed by circulating progenitor cells. Circulation. 2003;108:3122–3127. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105722.96112.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill JM, Zalos G, Halcox JP, Schenke WH, Waclawiw MA, Quyyumi AA, Finkel T. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells, vascular function, and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:593–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi T, Kalka C, Masuda H, Chen D, Silver M, Kearney M, Magner M, Isner JM, Asahara T. Ischemia- and cytokine-induced mobilization of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells for neovascularization. Nat Med. 1999;5:434–438. doi: 10.1038/7434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in health and disease. Nat Med. 2003;9:653–660. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urbich C, Heeschen C, Aicher A, Dernbach E, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Relevance of monocytic features for neovascularization capacity of circulating endothelial progenitor cells. Circulation. 2003;108:2511–2516. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000096483.29777.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Sipahi I, Libby P, Raichlen JS, Ballantyne CM, Davignon J, Erbel R, Fruchart JC, Tardif JC, et al. Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: the ASTEROID trial. JAMA. 2006;295:1556–1565. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.jpc60002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rafii S, Lyden D. Therapeutic stem and progenitor cell transplantation for organ vascularization and regeneration. Nat Med. 2003;9:702–712. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mukai N, Akahori T, Komaki M, Li Q, Kanayasu-Toyoda T, Ishii-Watabe A, Kobayashi A, Yamaguchi T, Abe M, Amagasa T, et al. A comparison of the tube forming potentials of early and late endothelial progenitor cells. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:430–440. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) Lancet. 1994;344:1383–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I, Isles CG, Lorimer AR, MacFarlane PW, McKillop JH, Packard CJ. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1301–1307. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511163332001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedersen TR, Berg K, Cook TJ, Faergeman O, Haghfelt T, Kjekshus J, Miettinen T, Musliner TA, Olsson AG, Pyörälä K, et al. Safety and tolerability of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin during 5 years in the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2085–2092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C, Kirby A, Sourjina T, Peto R, Collins R, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Influence of pravastatin and plasma lipids on clinical events in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study (WOSCOPS) Circulation. 1998;97:1440–1445. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.15.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan JK, Ng CS, Hui PK. A simple guide to the terminology and application of leucocyte monoclonal antibodies. Histopathology. 1988;12:461–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1988.tb01967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho IC, Tai TS, Pai SY. GATA3 and the T-cell lineage: essential functions before and after T-helper-2-cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:125–135. doi: 10.1038/nri2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folkman J. Angiogenesis in cancer, vascular, rheumatoid and other disease. Nat Med. 1995;1:27–31. doi: 10.1038/nm0195-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, Silver M, van der Zee R, Li T, Witzenbichler B, Schatteman G, Isner JM. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science. 1997;275:964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stump MM, Jordan GL, Debakey ME, Halpert B. Endothelium grown from circulating blood on isolated intravascular dacron hub. Am J Pathol. 1963;43:361–367. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asahara T, Masuda H, Takahashi T, Kalka C, Pastore C, Silver M, Kearne M, Magner M, Isner JM. Bone marrow origin of endothelial progenitor cells responsible for postnatal vasculogenesis in physiological and pathological neovascularization. Circ Res. 1999;85:221–228. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Risau W. Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Nature. 1997;386:671–674. doi: 10.1038/386671a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ingram DA, Caplice NM, Yoder MC. Unresolved questions, changing definitions, and novel paradigms for defining endothelial progenitor cells. Blood. 2005;106:1525–1531. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi Q, Rafii S, Wu MH, Wijelath ES, Yu C, Ishida A, Fujita Y, Kothari S, Mohle R, Sauvage LR, et al. Evidence for circulating bone marrow-derived endothelial cells. Blood. 1998;92:362–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin Y, Weisdorf DJ, Solovey A, Hebbel RP. Origins of circulating endothelial cells and endothelial outgrowth from blood. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:71–77. doi: 10.1172/JCI8071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peichev M, Naiyer AJ, Pereira D, Zhu Z, Lane WJ, Williams M, Oz MC, Hicklin DJ, Witte L, Moore MA, et al. Expression of VEGFR-2 and AC133 by circulating human CD34(+) cells identifies a population of functional endothelial precursors. Blood. 2000;95:952–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirschi KK, Ingram DA, Yoder MC. Assessing identity, phenotype, and fate of endothelial progenitor cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1584–1595. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.155960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fadini GP, Losordo D, Dimmeler S. Critical reevaluation of endothelial progenitor cell phenotypes for therapeutic and diagnostic use. Circ Res. 2012;110:624–637. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fadini GP, Baesso I, Albiero M, Sartore S, Agostini C, Avogaro A. Technical notes on endothelial progenitor cells: ways to escape from the knowledge plateau. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hristov M, Erl W, Weber PC. Endothelial progenitor cells: mobilization, differentiation, and homing. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1185–1189. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000073832.49290.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urbich C, Dimmeler S. Endothelial progenitor cells: characterization and role in vascular biology. Circ Res. 2004;95:343–353. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000137877.89448.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yin AH, Miraglia S, Zanjani ED, Almeida-Porada G, Ogawa M, Leary AG, Olweus J, Kearney J, Buck DW. AC133, a novel marker for human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 1997;90:5002–5012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quirici N, Soligo D, Caneva L, Servida F, Bossolasco P, Deliliers GL. Differentiation and expansion of endothelial cells from human bone marrow CD133(+) cells. Br J Haematol. 2001;115:186–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bertolini F, Shaked Y, Mancuso P, Kerbel RS. The multifaceted circulating endothelial cell in cancer: towards marker and target identification. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:835–845. doi: 10.1038/nrc1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Timmermans F, Van Hauwermeiren F, De Smedt M, Raedt R, Plasschaert F, De Buyzere ML, Gillebert TC, Plum J, Vandekerckhove B. Endothelial outgrowth cells are not derived from CD133+ cells or CD45+ hematopoietic precursors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1572–1579. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.144972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Friedrich EB, Walenta K, Scharlau J, Nickenig G, Werner N. CD34-/CD133+/VEGFR-2+ endothelial progenitor cell subpopulation with potent vasoregenerative capacities. Circ Res. 2006;98:e20–e25. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000205765.28940.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gill M, Dias S, Hattori K, Rivera ML, Hicklin D, Witte L, Girardi L, Yurt R, Himel H, Rafii S. Vascular trauma induces rapid but transient mobilization of VEGFR2(+)AC133(+) endothelial precursor cells. Circ Res. 2001;88:167–174. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Case J, Mead LE, Bessler WK, Prater D, White HA, Saadatzadeh MR, Bhavsar JR, Yoder MC, Haneline LS, Ingram DA. Human CD34+AC133+VEGFR-2+ cells are not endothelial progenitor cells but distinct, primitive hematopoietic progenitors. Exp Hematol. 2007;35:1109–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmidt-Lucke C, Fichtlscherer S, Aicher A, Tschöpe C, Schultheiss HP, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Quantification of circulating endothelial progenitor cells using the modified ISHAGE protocol. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farace F, Gross-Goupil M, Tournay E, Taylor M, Vimond N, Jacques N, Billiot F, Mauguen A, Hill C, Escudier B. Levels of circulating CD45(dim)CD34(+)VEGFR2(+) progenitor cells correlate with outcome in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:1144–1150. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmidt-Lucke C, Rössig L, Fichtlscherer S, Vasa M, Britten M, Kämper U, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Reduced number of circulating endothelial progenitor cells predicts future cardiovascular events: proof of concept for the clinical importance of endogenous vascular repair. Circulation. 2005;111:2981–2987. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.504340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Padfield GJ, Newby DE, Mills NL. Understanding the role of endothelial progenitor cells in percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1553–1565. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schächinger V, Britten MB, Zeiher AM. Prognostic impact of coronary vasodilator dysfunction on adverse long-term outcome of coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2000;101:1899–1906. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.16.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suwaidi JA, Hamasaki S, Higano ST, Nishimura RA, Holmes DR, Lerman A. Long-term follow-up of patients with mild coronary artery disease and endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2000;101:948–954. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.9.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Halcox JP, Schenke WH, Zalos G, Mincemoyer R, Prasad A, Waclawiw MA, Nour KR, Quyyumi AA. Prognostic value of coronary vascular endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2002;106:653–658. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000025404.78001.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gokce N, Keaney JF, Hunter LM, Watkins MT, Menzoian JO, Vita JA. Risk stratification for postoperative cardiovascular events via noninvasive assessment of endothelial function: a prospective study. Circulation. 2002;105:1567–1572. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012543.55874.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rouhl RP, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Damoiseaux J, Tervaert JW, Lodder J. Endothelial progenitor cell research in stroke: a potential shift in pathophysiological and therapeutical concepts. Stroke. 2008;39:2158–2165. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.507251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sen S, McDonald SP, Coates PT, Bonder CS. Endothelial progenitor cells: novel biomarker and promising cell therapy for cardiovascular disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2011;120:263–283. doi: 10.1042/CS20100429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dimmeler S, Vasa-Nicotera M. Aging of progenitor cells: limitation for regenerative capacity? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:2081–2082. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lambiase PD, Edwards RJ, Anthopoulos P, Rahman S, Meng YG, Bucknall CA, Redwood SR, Pearson JD, Marber MS. Circulating humoral factors and endothelial progenitor cells in patients with differing coronary collateral support. Circulation. 2004;109:2986–2992. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130639.97284.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vasa M, Fichtlscherer S, Aicher A, Adler K, Urbich C, Martin H, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Number and migratory activity of circulating endothelial progenitor cells inversely correlate with risk factors for coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2001;89:E1–E7. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.093953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chironi G, Walch L, Pernollet MG, Gariepy J, Levenson J, Rendu F, Simon A. Decreased number of circulating CD34+KDR+ cells in asymptomatic subjects with preclinical atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2007;191:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Werner N, Wassmann S, Ahlers P, Schiegl T, Kosiol S, Link A, Walenta K, Nickenig G. Endothelial progenitor cells correlate with endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease. Basic Res Cardiol. 2007;102:565–571. doi: 10.1007/s00395-007-0680-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Werner N, Kosiol S, Schiegl T, Ahlers P, Walenta K, Link A, Böhm M, Nickenig G. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells and cardiovascular outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:999–1007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kunz GA, Liang G, Cuculi F, Gregg D, Vata KC, Shaw LK, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Dong C, Taylor DA, Peterson ED. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells predict coronary artery disease severity. Am Heart J. 2006;152:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gaspardone A, Menghini F, Mazzuca V, Skossyreva O, Barbato G, de Fabritiis P. Progenitor cell mobilisation in patients with acute and chronic coronary artery disease. Heart. 2006;92:253–254. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.058636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Güven H, Shepherd RM, Bach RG, Capoccia BJ, Link DC. The number of endothelial progenitor cell colonies in the blood is increased in patients with angiographically significant coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1579–1587. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shintani S, Murohara T, Ikeda H, Ueno T, Honma T, Katoh A, Sasaki K, Shimada T, Oike Y, Imaizumi T. Mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;103:2776–2779. doi: 10.1161/hc2301.092122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wojakowski W, Tendera M, Michałowska A, Majka M, Kucia M, Maślankiewicz K, Wyderka R, Ochała A, Ratajczak MZ. Mobilization of CD34/CXCR4+, CD34/CD117+, c-met+ stem cells, and mononuclear cells expressing early cardiac, muscle, and endothelial markers into peripheral blood in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;110:3213–3220. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147609.39780.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Massa M, Rosti V, Ferrario M, Campanelli R, Ramajoli I, Rosso R, De Ferrari GM, Ferlini M, Goffredo L, Bertoletti A, et al. Increased circulating hematopoietic and endothelial progenitor cells in the early phase of acute myocardial infarction. Blood. 2005;105:199–206. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leone AM, Rutella S, Bonanno G, Abbate A, Rebuzzi AG, Giovannini S, Lombardi M, Galiuto L, Liuzzo G, Andreotti F, et al. Mobilization of bone marrow-derived stem cells after myocardial infarction and left ventricular function. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1196–1204. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Banerjee S, Brilakis E, Zhang S, Roesle M, Lindsey J, Philips B, Blewett CG, Terada LS. Endothelial progenitor cell mobilization after percutaneous coronary intervention. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Laufs U, Liao JK. Targeting Rho in cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2000;87:526–528. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.7.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Istvan ES. Structural mechanism for statin inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase. Am Heart J. 2002;144:S27–S32. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.130300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vasa M, Fichtlscherer S, Adler K, Aicher A, Martin H, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Increase in circulating endothelial progenitor cells by statin therapy in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2001;103:2885–2890. doi: 10.1161/hc2401.092816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1349–1357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811053391902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, Rouleau JL, Rutherford JD, Cole TG, Brown L, Warnica JW, Arnold JM, Wun CC, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. Cholesterol and Recurrent Events Trial investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1001–1009. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610033351401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.LaRosa JC, Grundy SM, Waters DD, Shear C, Barter P, Fruchart JC, Gotto AM, Greten H, Kastelein JJ, Shepherd J, et al. Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1425–1435. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ridker PM, Morrow DA, Rose LM, Rifai N, Cannon CP, Braunwald E. Relative efficacy of atorvastatin 80 mg and pravastatin 40 mg in achieving the dual goals of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol & lt; 70 mg/dl and C-reactive protein & lt; 2 mg/l: an analysis of the PROVE-IT TIMI-22 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1644–1648. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, Ganz P, Oliver MF, Waters D, Zeiher A, Chaitman BR, Leslie S, Stern T. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes: the MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1711–1718. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.13.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maron DJ, Fazio S, Linton MF. Current perspectives on statins. Circulation. 2000;101:207–213. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lacoste L, Lam JY, Hung J, Letchacovski G, Solymoss CB, Waters D. Hyperlipidemia and coronary disease. Correction of the increased thrombogenic potential with cholesterol reduction. Circulation. 1995;92:3172–3177. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.11.3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Schoenhagen P, Brown BG, Ganz P, Vogel RA, Crowe T, Howard G, Cooper CJ, Brodie B, et al. Effect of intensive compared with moderate lipid-lowering therapy on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1071–1080. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Patti G, Cannon CP, Murphy SA, Mega S, Pasceri V, Briguori C, Colombo A, Yun KH, Jeong MH, Kim JS, et al. Clinical benefit of statin pretreatment in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a collaborative patient-level meta-analysis of 13 randomized studies. Circulation. 2011;123:1622–1632. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.002451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Di Sciascio G, Patti G, Pasceri V, Gaspardone A, Colonna G, Montinaro A. Efficacy of atorvastatin reload in patients on chronic statin therapy undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the ARMYDA-RECAPTURE (Atorvastatin for Reduction of Myocardial Damage During Angioplasty) Randomized Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:558–565. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, Casey DE, Ganiats TG, Holmes DR, Jaffe AS, Jneid H, Kelly RF, Kontos MC, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients with Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:e139–e228. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127:e362–e425. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bustos C, Hernández-Presa MA, Ortego M, Tuñón J, Ortega L, Pérez F, Díaz C, Hernández G, Egido J. HMG-CoA reductase inhibition by atorvastatin reduces neointimal inflammation in a rabbit model of atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:2057–2064. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00487-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Laufs U, Gertz K, Huang P, Nickenig G, Böhm M, Dirnagl U, Endres M. Atorvastatin upregulates type III nitric oxide synthase in thrombocytes, decreases platelet activation, and protects from cerebral ischemia in normocholesterolemic mice. Stroke. 2000;31:2442–2449. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dogra GK, Watts GF, Chan DC, Stanton K. Statin therapy improves brachial artery vasodilator function in patients with Type 1 diabetes and microalbuminuria. Diabet Med. 2005;22:239–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dangas G, Smith DA, Unger AH, Shao JH, Meraj P, Fier C, Cohen AM, Fallon JT, Badimon JJ, Ambrose JA. Pravastatin: an antithrombotic effect independent of the cholesterol-lowering effect. Thromb Haemost. 2000;83:688–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dimmeler S, Aicher A, Vasa M, Mildner-Rihm C, Adler K, Tiemann M, Rütten H, Fichtlscherer S, Martin H, Zeiher AM. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) increase endothelial progenitor cells via the PI 3-kinase/Akt pathway. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:391–397. doi: 10.1172/JCI13152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Laufs U, La Fata V, Plutzky J, Liao JK. Upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by HMG CoA reductase inhibitors. Circulation. 1998;97:1129–1135. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.12.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kureishi Y, Luo Z, Shiojima I, Bialik A, Fulton D, Lefer DJ, Sessa WC, Walsh K. The HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor simvastatin activates the protein kinase Akt and promotes angiogenesis in normocholesterolemic animals. Nat Med. 2000;6:1004–1010. doi: 10.1038/79510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Laufs U, Liao JK. Post-transcriptional regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase mRNA stability by Rho GTPase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24266–24271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.24266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Aicher A, Heeschen C, Mildner-Rihm C, Urbich C, Ihling C, Technau-Ihling K, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Essential role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase for mobilization of stem and progenitor cells. Nat Med. 2003;9:1370–1376. doi: 10.1038/nm948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Llevadot J, Murasawa S, Kureishi Y, Uchida S, Masuda H, Kawamoto A, Walsh K, Isner JM, Asahara T. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor mobilizes bone marrow--derived endothelial progenitor cells. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:399–405. doi: 10.1172/JCI13131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bush LR, Shebuski RJ. In vivo models of arterial thrombosis and thrombolysis. FASEB J. 1990;4:3087–3098. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.13.2210155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Urbich C, Dernbach E, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Double-edged role of statins in angiogenesis signaling. Circ Res. 2002;90:737–744. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000014081.30867.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Deschaseaux F, Selmani Z, Falcoz PE, Mersin N, Meneveau N, Penfornis A, Kleinclauss C, Chocron S, Etievent JP, Tiberghien P, et al. Two types of circulating endothelial progenitor cells in patients receiving long term therapy by HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;562:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hristov M, Fach C, Becker C, Heussen N, Liehn EA, Blindt R, Hanrath P, Weber C. Reduced numbers of circulating endothelial progenitor cells in patients with coronary artery disease associated with long-term statin treatment. Atherosclerosis. 2007;192:413–420. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lin LY, Huang CC, Chen JS, Wu TC, Leu HB, Huang PH, Chang TT, Lin SJ, Chen JW. Effects of pitavastatin versus atorvastatin on the peripheral endothelial progenitor cells and vascular endothelial growth factor in high-risk patients: a pilot prospective, double-blind, randomized study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:111. doi: 10.1186/s12933-014-0111-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Leone AM, Rutella S, Giannico MB, Perfetti M, Zaccone V, Brugaletta S, Garramone B, Niccoli G, Porto I, Liuzzo G, et al. Effect of intensive vs standard statin therapy on endothelial progenitor cells and left ventricular function in patients with acute myocardial infarction: Statins for regeneration after acute myocardial infarction and PCI (STRAP) trial. Int J Cardiol. 2008;130:457–462. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ye H, He F, Fei X, Lou Y, Wang S, Yang R, Hu Y, Chen X. High-dose atorvastatin reloading before percutaneous coronary intervention increased circulating endothelial progenitor cells and reduced inflammatory cytokine expression during the perioperative period. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2014;19:290–295. doi: 10.1177/1074248413513500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ricottini EMR, Patti G. Benefit of atorvastatin reload on endothelial progenitor cells in patients on chronic statin treatment undergoing PCI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:10. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Knowles RG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide synthases in mammals. Biochem J. 1994;298(Pt 2):249–258. doi: 10.1042/bj2980249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Moncada S, Higgs A. The L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:2002–2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sessa WC. The nitric oxide synthase family of proteins. J Vasc Res. 1994;31:131–143. doi: 10.1159/000159039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Moncada S, Palmer RM, Higgs EA. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wilcox JN, Subramanian RR, Sundell CL, Tracey WR, Pollock JS, Harrison DG, Marsden PA. Expression of multiple isoforms of nitric oxide synthase in normal and atherosclerotic vessels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:2479–2488. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Stuehr DJ, Griffith OW. Mammalian nitric oxide synthases. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1992;65:287–346. doi: 10.1002/9780470123119.ch8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Hermann C, Busse R, Zeiher AM. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399:601–605. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Dimmeler S, Kemp BE, Busse R. Phosphorylation of Thr(495) regulates Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity. Circ Res. 2001;88:E68–E75. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.092677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rubanyi GM, Vanhoutte PM. Superoxide anions and hyperoxia inactivate endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:H822–H827. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.250.5.H822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Carmeliet P. Mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Nat Med. 2000;6:389–395. doi: 10.1038/74651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407:249–257. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Semenza GL. Vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and arteriogenesis: mechanisms of blood vessel formation and remodeling. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:840–847. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wahlberg E. Angiogenesis and arteriogenesis in limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:198–203. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Landmesser U, Engberding N, Bahlmann FH, Schaefer A, Wiencke A, Heineke A, Spiekermann S, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Templin C, Kotlarz D, et al. Statin-induced improvement of endothelial progenitor cell mobilization, myocardial neovascularization, left ventricular function, and survival after experimental myocardial infarction requires endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2004;110:1933–1939. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143232.67642.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Matsuno H, Takei M, Hayashi H, Nakajima K, Ishisaki A, Kozawa O. Simvastatin enhances the regeneration of endothelial cells via VEGF secretion in injured arteries. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;43:333–340. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200403000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Liao JK, Shin WS, Lee WY, Clark SL. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein decreases the expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:319–324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Liao JK, Clark SL. Regulation of G-protein alpha i2 subunit expression by oxidized low-density lipoprotein. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1457–1463. doi: 10.1172/JCI117816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tamai O, Matsuoka H, Itabe H, Wada Y, Kohno K, Imaizumi T. Single LDL apheresis improves endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in hypercholesterolemic humans. Circulation. 1997;95:76–82. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.López-Farré A, Caramelo C, Esteban A, Alberola ML, Millás I, Montón M, Casado S. Effects of aspirin on platelet-neutrophil interactions. Role of nitric oxide and endothelin-1. Circulation. 1995;91:2080–2088. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.7.2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Latini R, Bianchi M, Correale E, Dinarello CA, Fantuzzi G, Fresco C, Maggioni AP, Mengozzi M, Romano S, Shapiro L. Cytokines in acute myocardial infarction: selective increase in circulating tumor necrosis factor, its soluble receptor, and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1994;23:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ma XL, Weyrich AS, Lefer DJ, Lefer AM. Diminished basal nitric oxide release after myocardial ischemia and reperfusion promotes neutrophil adherence to coronary endothelium. Circ Res. 1993;72:403–412. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.2.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Assmus B, Urbich C, Aicher A, Hofmann WK, Haendeler J, Rössig L, Spyridopoulos I, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors reduce senescence and increase proliferation of endothelial progenitor cells via regulation of cell cycle regulatory genes. Circ Res. 2003;92:1049–1055. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000070067.64040.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kusuyama T, Omura T, Nishiya D, Enomoto S, Matsumoto R, Murata T, Takeuchi K, Yoshikawa J, Yoshiyama M. The effects of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor on vascular progenitor cells. J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;101:344–349. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0060102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Laufs U, Fata VL, Liao JK. Inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl (HMG)-CoA reductase blocks hypoxia-mediated down-regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31725–31729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Davis ME, Cai H, McCann L, Fukai T, Harrison DG. Role of c-Src in regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression during exercise training. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1449–H1453. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00918.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kosmidou I, Moore JP, Weber M, Searles CD. Statin treatment and 3’ polyadenylation of eNOS mRNA. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2642–2649. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.154492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Minami Y, Satoh M, Maesawa C, Takahashi Y, Tabuchi T, Itoh T, Nakamura M. Effect of atorvastatin on microRNA 221 / 222 expression in endothelial progenitor cells obtained from patients with coronary artery disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2009;39:359–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Petersen CP, Bordeleau ME, Pelletier J, Sharp PA. Short RNAs repress translation after initiation in mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 2006;21:533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Felli N, Fontana L, Pelosi E, Botta R, Bonci D, Facchiano F, Liuzzi F, Lulli V, Morsilli O, Santoro S, et al. MicroRNAs 221 and 222 inhibit normal erythropoiesis and erythroleukemic cell growth via kit receptor down-modulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18081–18086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506216102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Cerda A, Fajardo CM, Basso RG, Hirata MH, Hirata RD. Role of microRNAs 221/222 on statin induced nitric oxide release in human endothelial cells. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2015;104:195–201. doi: 10.5935/abc.20140192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kuehbacher A, Urbich C, Dimmeler S. Targeting microRNA expression to regulate angiogenesis. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:12–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Bader AG, Kang S, Zhao L, Vogt PK. Oncogenic PI3K deregulates transcription and translation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:921–929. doi: 10.1038/nrc1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Akt takes center stage in angiogenesis signaling. Circ Res. 2000;86:4–5. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Whitman M, Downes CP, Keeler M, Keller T, Cantley L. Type I phosphatidylinositol kinase makes a novel inositol phospholipid, phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate. Nature. 1988;332:644–646. doi: 10.1038/332644a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Toker A, Cantley LC. Signalling through the lipid products of phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase. Nature. 1997;387:673–676. doi: 10.1038/42648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Karar J, Maity A. PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway in Angiogenesis. Front Mol Neurosci. 2011;4:51. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kawasaki K, Smith RS, Hsieh CM, Sun J, Chao J, Liao JK. Activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase Akt pathway mediates nitric oxide-induced endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5726–5737. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5726-5737.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Ellis LM, Hicklin DJ. VEGF-targeted therapy: mechanisms of anti-tumour activity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrc2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Morales-Ruiz M, Fulton D, Sowa G, Languino LR, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Sessa WC. Vascular endothelial growth factor-stimulated actin reorganization and migration of endothelial cells is regulated via the serine/threonine kinase Akt. Circ Res. 2000;86:892–896. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.8.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Papapetropoulos A, García-Cardeña G, Madri JA, Sessa WC. Nitric oxide production contributes to the angiogenic properties of vascular endothelial growth factor in human endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:3131–3139. doi: 10.1172/JCI119868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Fulton D, Gratton JP, McCabe TJ, Fontana J, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Franke TF, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa WC. Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the protein kinase Akt. Nature. 1999;399:597–601. doi: 10.1038/21218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Dimmeler S, Dernbach E, Zeiher AM. Phosphorylation of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase at ser-1177 is required for VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration. FEBS Lett. 2000;477:258–262. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01657-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Bahlmann FH, De Groot K, Spandau JM, Landry AL, Hertel B, Duckert T, Boehm SM, Menne J, Haller H, Fliser D. Erythropoietin regulates endothelial progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;103:921–926. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Rikitake Y, Liao JK. Rho GTPases, statins, and nitric oxide. Circ Res. 2005;97:1232–1235. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000196564.18314.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Lemoine S, Zhu L, Legallois D, Massetti M, Manrique A, Hanouz JL. Atorvastatin-induced cardioprotection of human myocardium is mediated by the inhibition of mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening via tumor necrosis factor-α and Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription pathway. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:1373–1384. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31828a7039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Sanada S, Asanuma H, Minamino T, Node K, Takashima S, Okuda H, Shinozaki Y, Ogai A, Fujita M, Hirata A, et al. Optimal windows of statin use for immediate infarct limitation: 5’-nucleotidase as another downstream molecule of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Circulation. 2004;110:2143–2149. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143830.59419.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Solenkova NV, Solodushko V, Cohen MV, Downey JM. Endogenous adenosine protects preconditioned heart during early minutes of reperfusion by activating Akt. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H441–H449. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00589.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. New directions for protecting the heart against ischaemia-reperfusion injury: targeting the Reperfusion Injury Salvage Kinase (RISK)-pathway. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:448–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Efthymiou CA, Mocanu MM, Yellon DM. Atorvastatin and myocardial reperfusion injury: new pleiotropic effect implicating multiple prosurvival signaling. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2005;45:247–252. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000154376.82445.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Hibbert B, Ma X, Pourdjabbar A, Simard T, Rayner K, Sun J, Chen YX, Filion L, O’Brien ER. Pre-procedural atorvastatin mobilizes endothelial progenitor cells: clues to the salutary effects of statins on healing of stented human arteries. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Baran Ç, Durdu S, Dalva K, Zaim Ç, Dogan A, Ocakoglu G, Gürman G, Arslan Ö, Akar AR. Effects of preoperative short term use of atorvastatin on endothelial progenitor cells after coronary surgery: a randomized, controlled trial. Stem Cell Rev. 2012;8:963–971. doi: 10.1007/s12015-011-9321-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Schmidt-Lucke C, Fichtlscherer S, Rössig L, Kämper U, Dimmeler S. Improvement of endothelial damage and regeneration indexes in patients with coronary artery disease after 4 weeks of statin therapy. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211:249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Tousoulis D, Andreou I, Tsiatas M, Miliou A, Tentolouris C, Siasos G, Papageorgiou N, Papadimitriou CA, Dimopoulos MA, Stefanadis C. Effects of rosuvastatin and allopurinol on circulating endothelial progenitor cells in patients with congestive heart failure: the impact of inflammatory process and oxidative stress. Atherosclerosis. 2011;214:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Jialal I, Devaraj S, Singh U, Huet BA. Decreased number and impaired functionality of endothelial progenitor cells in subjects with metabolic syndrome: implications for increased cardiovascular risk. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Cohen MV, Yang XM, Downey JM. Nitric oxide is a preconditioning mimetic and cardioprotectant and is the basis of many available infarct-sparing strategies. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Scalia R, Gooszen ME, Jones SP, Hoffmeyer M, Rimmer DM, Trocha SD, Huang PL, Smith MB, Lefer AM, Lefer DJ. Simvastatin exerts both anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective effects in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2001;103:2598–2603. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.21.2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Wassmann S, Laufs U, Müller K, Konkol C, Ahlbory K, Bäumer AT, Linz W, Böhm M, Nickenig G. Cellular antioxidant effects of atorvastatin in vitro and in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:300–305. doi: 10.1161/hq0202.104081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Mensah K, Mocanu MM, Yellon DM. Failure to protect the myocardium against ischemia/reperfusion injury after chronic atorvastatin treatment is recaptured by acute atorvastatin treatment: a potential role for phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1287–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Mihos CG, Pineda AM, Santana O. Cardiovascular effects of statins, beyond lipid-lowering properties. Pharmacol Res. 2014;88:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Tousoulis D, Andreou I, Antoniades C, Tentolouris C, Stefanadis C. Role of inflammation and oxidative stress in endothelial progenitor cell function and mobilization: therapeutic implications for cardiovascular diseases. Atherosclerosis. 2008;201:236–247. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Yao EH, Yu Y, Fukuda N. Oxidative stress on progenitor and stem cells in cardiovascular diseases. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2006;7:101–108. doi: 10.2174/138920106776597685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Morel DW, DiCorleto PE, Chisolm GM. Endothelial and smooth muscle cells alter low density lipoprotein in vitro by free radical oxidation. Arteriosclerosis. 1984;4:357–364. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.4.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Lamb DJ, Wilkins GM, Leake DS. The oxidative modification of low density lipoprotein by human lymphocytes. Atherosclerosis. 1992;92:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(92)90277-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Lim S, Barter P. Antioxidant effects of statins in the management of cardiometabolic disorders. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2014;21:997–1010. doi: 10.5551/jat.24398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Carracedo J, Merino A, Briceño C, Soriano S, Buendía P, Calleros L, Rodriguez M, Martín-Malo A, Aljama P, Ramírez R. Carbamylated low-density lipoprotein induces oxidative stress and accelerated senescence in human endothelial progenitor cells. FASEB J. 2011;25:1314–1322. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-173377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Tso C, Martinic G, Fan WH, Rogers C, Rye KA, Barter PJ. High-density lipoproteins enhance progenitor-mediated endothelium repair in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1144–1149. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000216600.37436.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Griendling KK, FitzGerald GA. Oxidative stress and cardiovascular injury: Part II: animal and human studies. Circulation. 2003;108:2034–2040. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093661.90582.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Thum T, Fraccarollo D, Schultheiss M, Froese S, Galuppo P, Widder JD, Tsikas D, Ertl G, Bauersachs J. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling impairs endothelial progenitor cell mobilization and function in diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:666–674. doi: 10.2337/db06-0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Urbich C, Knau A, Fichtlscherer S, Walter DH, Brühl T, Potente M, Hofmann WK, de Vos S, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. FOXO-dependent expression of the proapoptotic protein Bim: pivotal role for apoptosis signaling in endothelial progenitor cells. FASEB J. 2005;19:974–976. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2727fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]