Abstract

Background

Heavy water (2H2O) labelling of DNA enables the measurement of low-level cell proliferation in vivo, using gas chromatography/pyrolysis isotope ratio mass spectrometry (GC/P/IRMS), but the methodology has been too complex for widespread use. Here, we report a simplified method for measuring proliferation of malignant B cells in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Design and Methods

Patients were labelled with 2H2O for 6 weeks; blood samples were obtained at 0, 3, and 6 weeks during 2H2O labelling and 9, 12, and 16 weeks thereafter. Bone marrow was sampled at week 6. Phlebotomy was performed at multiple, non-research clinical sites. CLL cells were isolated in a central laboratory, using a novel RosetteSep™-based method; DNA labelling was analysed by GC/P/IRMS.

Results

In 26 of 29 patients, CLL cell isolation resulted in ≥ 95% purity for malignant CD5+ B cells; in one patient, malignant cells expressed marginal levels of CD5, and in two others, further sorting of CD5hi malignant cells was required. Cell yields correlated with white blood cell counts and exceeded GC/P/IRMS requirements (≈ 107 cells) > 98% of the time; high-quality DNA labelling data were obtained. RosetteSep isolation achieved adequate CLL cell purity from bone marrow in only 64% of samples, but greatly reduced subsequent sort time for impure samples.

Conclusion

This method enables clinical studies of CLL cell proliferation outside of research settings, using a shorter 2H2O intake protocol, a minimal sampling protocol, and centralised sample processing. The CLL cell isolation protocol may also prove useful in other applications. (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00481858)

Introduction

Abnormalities in cell proliferation and/or death are key components of malignancy. Traditionally, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) was considered a disease resulting from a reduction in the cell death rate with minimal proliferation of the leukemic clone (1). However, using 2H2O labelling as a marker of cell proliferation in vivo (2), it was recently revealed that patients with CLL have, in fact, a previously under-appreciated level of proliferation of malignant cells (3). While further data have suggested that fractional proliferation rates of CLL cells may be less than for normal B-cells (4, 5), significant inter patient variation in proliferation rates exist, and initial data has suggested that the rate of CLL cell proliferation correlates with disease activity (3). Thus, cell proliferation may be a prognostic marker for disease progression.

An obstacle to testing this hypothesis in a larger study and developing this test for widespread use is that the method previously used requires on-site expertise and lengthy 2H2O labelling times, making a large, multi-center trial difficult. In order to obtain sufficient enrichment in CLL cells for GC/MS analysis, it was necessary to have patients ingest 2H2O for 12 weeks or more, and 10 or more blood samples were obtained over a period of 6 months or more (3). In addition, CLL cells were isolated using a multi-step method (Ficoll density gradient isolation from blood taken in the preceding 24 hours, followed by MACS depletion and enrichment), which was performed at the clinical research site.

We have recently shown the feasibility of using isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) to measure very low levels of deuterium incorporation into DNA (6), allowing significantly shorter labelling times. The goal of the present study was to shorten and simplify the 2H2O labelling protocol for measuring CLL cell proliferation using IRMS and to enable its use in clinical settings without immediate access to a research laboratory. To that end, we had the goal of developing a single-step method of CLL cell isolation that would require no expertise at the local site other than phlebotomy, would work on samples up to 48 hours old, and would provide ≥107 CLL cells per 10 ml of blood with a purity of greater than >95%. We also investigated whether the method developed could be applied to yield CLL cells from bone marrow aspirates.

Design and Methods

Clinical study and 2H2O labelling of CLL patients

The study protocol was approved and monitored by the North Shore-Long Island Jewish (NS-LIJ) Health System’s Institutional Review Board. Patients diagnosed with early stage CLL (Rai stages 0–2) (7) were enrolled at LIJ Medical Center and NS University Hospital following informed consent. Patients with prior CLL treatment or those likely to need treatment in the first 16 weeks of the protocol were excluded.

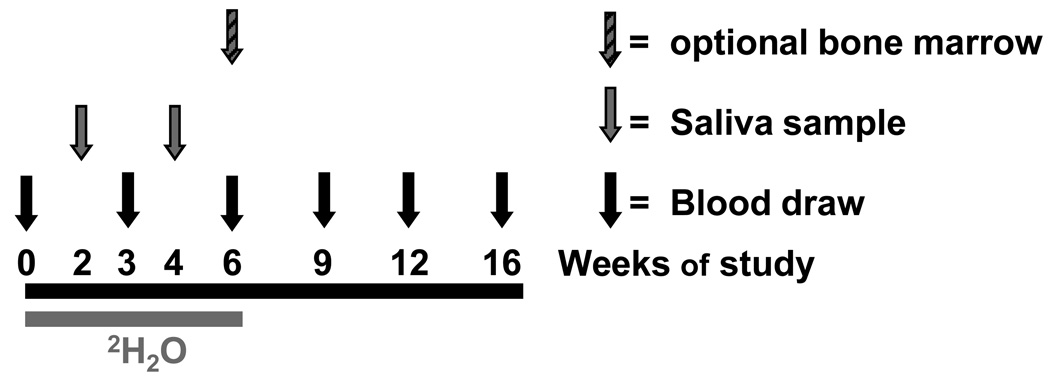

Following enrolment and a baseline blood draw, patients were given 50 ml of 2H2O (70% enriched, Spectra Gases Inc., Branchburg NJ) three times a day for 5 days (loading-bolus period), followed by 60 ml daily thereafter (maintenance), for a total of six weeks of labeling (Fig. 1) with a goal plateau body water enrichment of 1–1.5%. Saliva samples, used to determine body water enrichment and ensure compliance with 2H2O administration, were obtained by the patients at home with a Salivette kit (Sarstedt, Newton, NC) at weeks 2 and 4. Saliva samples were shipped to KineMed, Inc., at room temperature.

Figure 1. Heavy water study protocol.

Patients receive 2H2O orally for six weeks, with blood and saliva collected as indicated for determination of body water enrichment. CLL cells were purified from blood samples, and 2H enrichment in DNA was determined. An optional bone marrow biopsy was obtained at week 6.

At weeks 0, 3, 6, 9, 12 and 16, (see Fig. 1), 20 ml blood samples were obtained in desiccated heparin. Blood was collected either at NS-LIJ or at the patient’s local laboratory. Samples were shipped at room temperature by overnight courier to KineMed, Inc., for cell and serum isolation. An additional 10 ml of blood was processed at a local clinical laboratory for complete blood count (CBC), differential analysis, and absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) determination. An optional bone marrow aspirate was obtained at the 6-week time point and shipped at room temperature to KineMed, Inc.

Cell isolation

CLL cells were isolated from whole blood and bone marrow using the RosetteSep™ B-Cell isolation cocktail (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver Canada) per the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 10 ml whole blood was incubated with 500 µl B-cell enrichment cocktail for 20 min at room temperature. This cocktail comprises bispecific antibody constructs that cross-link unwanted cell lineages to erythrocytes, allowing their removal by density gradient centrifugation. The enrichment mixture was diluted with 1 volume of 2% fetal bovine serum (v/v; FBS) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and overlaid onto 15 ml DML solution (Stem Cell). Following centrifugation at 1200 × g for 20 minutes, the B cell-enriched gradient interface was removed and washed with 10 ml 2% FBS in PBS. Cell viability and numbers were determined by Trypan Blue exclusion. If purity (determined as below) was < 95%, stained cells were fixed with 10% buffered formalin solution and separated within 48 hours on a Beckman-Coulter Epics Elite cell sorter. Nucleated cells were gated, and CD19+/CD5+ cells were collected at a flow rate setting of ≤ 50, at ≤ 5000 cells per second. Sorted populations were reanalysed to ensure > 95% purity, and aliquots frozen as described below.

Determination of CLL cell purity

Cells (2 × 105 per sample) were stained with anti-CD19-FITC (Clone HIB19, eBiosciences) and anti-CD5-PE (Cat # 340697, Becton Dickinson) monoclonal antibodies, or with appropriate isotype controls, by incubation on ice for 15 min. Cells were washed twice with 2 ml 2% FBS-PBS and resuspended in 500 µl PBS containing 1 µl propidium iodide (1 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 µl DRAQ5 (5 mM; BioStatus Limited, Leicestershire, UK) to label cellular DNA. Cell surface marker expression, viability (propidium iodide exclusion), and DNA content were analyzed by flow cytometry using a Beckman-Coulter Epics XL Analyzer. CD5 and CD19 expression were quantified after gating on nucleated (DRAQ5+) cells regardless of viability. If >95% of nucleated cells were CD19+CD5+, purity was deemed sufficient for subsequent DNA enrichment analysis (8). Cell samples were split into aliquots (1–2 × 107 cells per microfuge tube) and pellets were stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Measurement of 2H incorporation into purine dR of DNA

For analysis of DNA enrichment by GC/P/IRMS, cell pellets were processed using the method of Voogt et al. (6) with modifications. Briefly, protein digestion was done with 50 µl of 20 mg/ml Proteinase K (Qiagen, Valencia CA) for 24–72 hours at 55 °C. The incubation time required for clarification was dependent on the cell counts: samples containing ≥ 2 × 107 cells typically required at least 48 hours. After proteinase K inactivation, digests were transferred to 5 kDa MWCO cellulose membrane filters (Sigma-Aldrich, cat# M0286) and columns were spun for 30–90 min at 5000 × g, trapping the DNA on the filter. A minority of samples that did not clarify during the protein digestion required longer spin times due to partial clogging of the spin filters. DNA hydrolysis, derivatization and GC/P/IRMS was as described previously (6). Samples were analyzed on a Finnegan MAT-253 IRMS instrument (ThermoFisher, Bremen, Germany) fitted with a DB-5ms column (Agilent, Santa Clara CA). Samples were injected in duplicate, and both cis and trans isomers of the deoxyribose (dR) derivative were assessed for enrichment and compared with enriched dR standards ranging from natural abundance to 3000 delta.

Measurement of body 2H2O enrichment

From each blood draw, a 500 µl aliquot of whole blood was centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min in a microfuge tube. Salivette tubes were centrifuged for 5min at 1,000 × g. The resulting sera and saliva were used for determination of 2H2O enrichment by cycloidal mass spectrometry (Monitor Instruments, Cheswick PA) as previously described (9).

Calculations

Body 2H2O enrichments

Body 2H2O enrichments were calculated by comparison to a gravimetrically prepared standard curve. Average body water enrichment during the labelling period, representing the precursor enrichment (p), was estimated from data obtained for saliva samples at weeks 2 and 4 and from plasma at weeks 3 and 6.

2H Enrichments in DNA – Calculation of APE and f

In order to calculate the percentage of new CLL cells (f) from GC/P/IRMS data, atom percent excess (APE) was first calculated from measured 2H-1H : 1H-1H abundance ratios in the GC peaks corresponding to the dR derivative (6). The maximal or asymptotic amount of 2H incorporation (APE*) for fully turned-over (100% new) DNA was calculated as:

where p is the precursor enrichment (as above) and the numerical conversion ratio corresponds to the number of hydrogen atoms in dR accessible to 2H2O labelling, divided by the number of hydrogen atoms in the derivative. Fractional DNA synthesis (f) was then calculated using the ratio of the measured APE to the APE*.

Results

Twenty-nine early-stage, therapy naive CLL patients were enrolled (n = 20 men, n = 9 women; mean age 56.5 ± 7.6 y, range 41.3–76.7 y; n = 13 at stage 0, n = 11 at stage 1, n = 5 at stage 2; mean time from diagnosis 2.8 ± 3.0 y, range 0.1–10.2 y). WBC counts ranged from 3.5 – 325.3 × 103/ µl.

B-CLL cell isolation – purity from blood

Blood samples were shipped to the KineMed central processing site by overnight courier. A total of 172 blood samples were available for analysis. During sample processing, 3 of the available samples were made unusable due to processing errors, leaving a total of 169 blood samples available for this analysis.

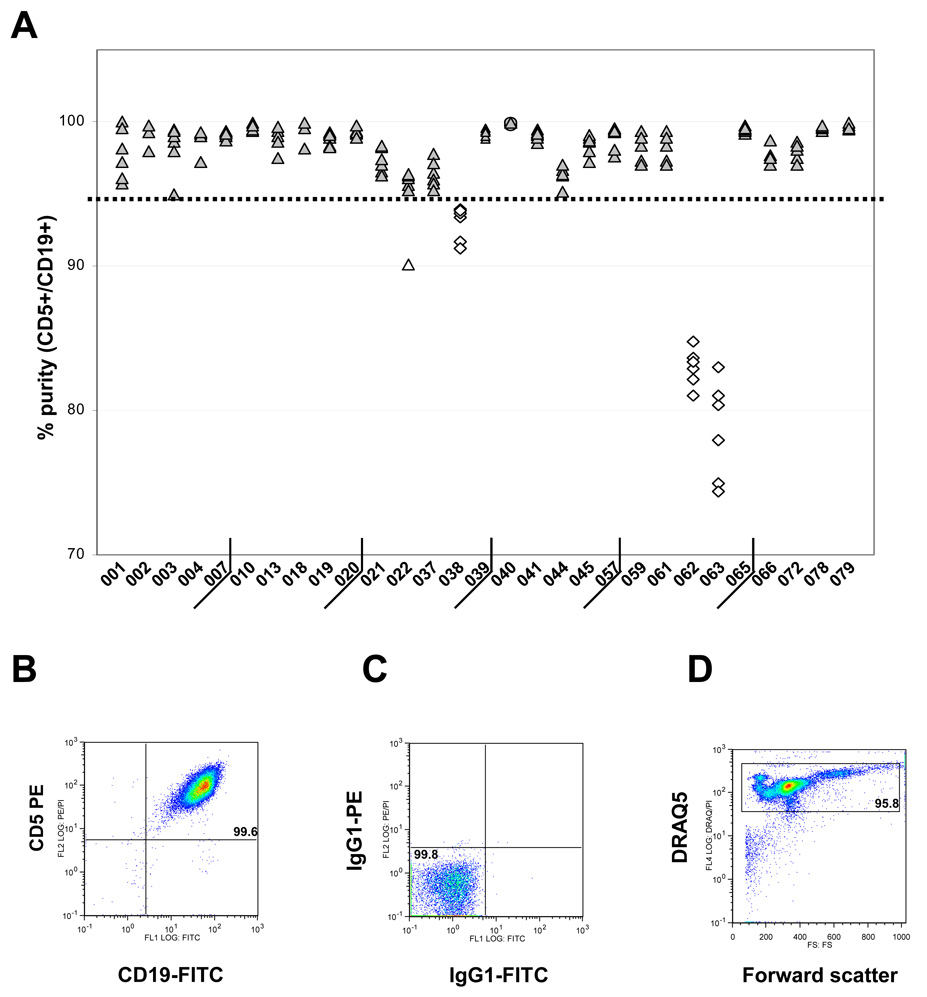

A single RosetteSep isolation step was sufficient to achieve ≥ 95% purity in 88% of samples (149 of 169, Fig. 2A). Purity was defined as the percentage of CD5+CD19+ cells; a representative flow cytometric analysis is shown in Fig. 2B, with cut-offs for positive staining set using isotype controls (Fig. 2C). No lymphocyte scatter gate was employed, to minimise the risk of overestimating purity due to scatter-based exclusion of nonviable cells and/or myeloid cells. Instead, nucleated cells were gated as DRAQ5+ events with a low forward scatter threshold (Fig. 2D), assuring that all sources of contamination would be detectable. Viability after RosetteSep isolation was excellent (average 95.6 ± 4.2%).

Figure 2. Purity of CLL cells isolated by the single-step RosetteSep method.

(A) Purity was determined as the percentage of CD5+CD19+ cells and plotted for repeated samples obtained from each patient. The bold dotted line indicates the 95% cutoff for sufficient purity. (B) Representative flow cytometry dot plot, showing a > 99% pure population of RosetteSep-isolated CD5+CD19+ B cells isolated at week 0 from patient CLL065. (C) Isotype control used to set cutoffs for positive staining. (D) Plot of forward scatter vs. DRAQ5 staining, showing gating of nucleated cells.

All but three samples were received and processed within 48 hours after phlebotomy. The other three samples were processed at 93, 96, and 169 hours following blood draw, due to delays in shipment. This did not impact the purity of isolated CLL cells (98%, 97%, and 99%, respectively), but did result in below average viability (91%, 88%, and 91%, respectively).

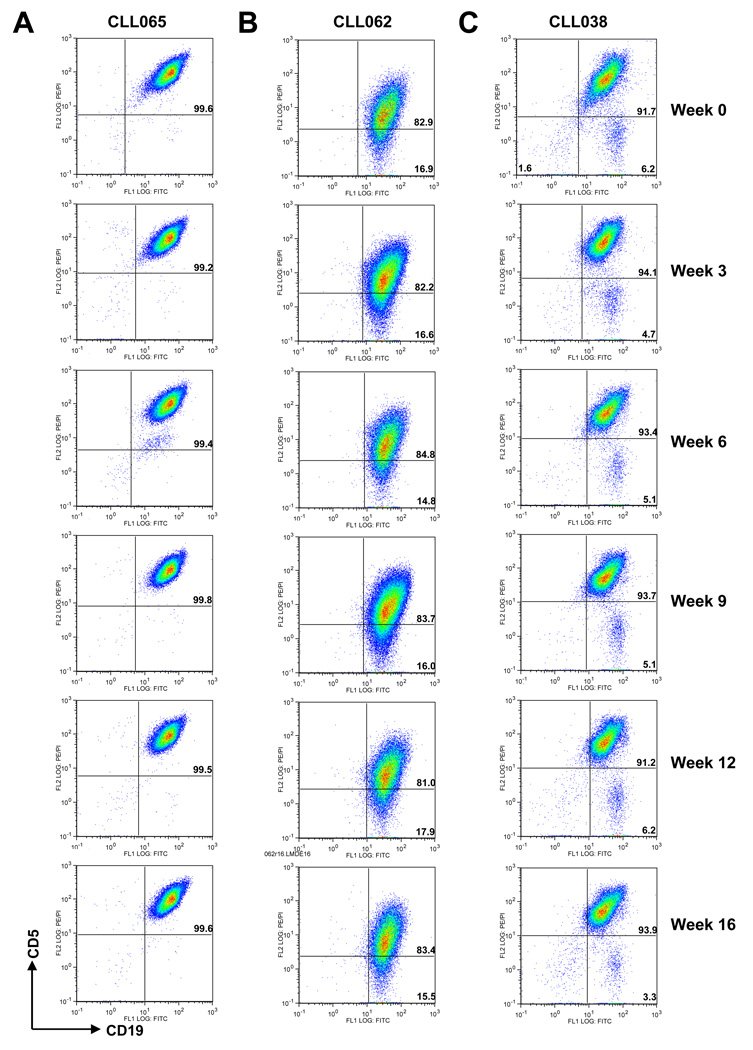

Fig. 2A shows that the majority of failures (18 of 19) were patient specific, as all samples from 3 of 29 patients (CLL038, CLL062, and CLL063) failed to reach the purity threshold of 95%. Fig. 3 compares CD5/CD19 expression for repeated RosetteSep isolates from two of these patients and one with good purity. Staining patterns obtained from successful serial isolations from the same patient were consistent throughout the 16-week study period (Fig. 3A, patient CLL065). Staining patterns for failed isolations were also consistent for a given patient (Fig. 3B, 3C, patients CLL062 and CLL038).

Figure 3. Flow cytometry profiles of isolated CLL cells over 16 weeks of study.

RosetteSep™ purified B cells of three representative CLL patients over 16 weeks of study were stained with CD19-FITC and CD5-PE antibodies and analysed by flow cytometry; per cent purity (% double-positive cells) is shown in the upper right quadrant of each plot. (A) CLL065 blood samples consistently provided > 95% pure CLL cells. (B) CLL062 RosetteSep™ purified cells exhibited low CD5 expression, while (C) CLL038 cells consistently presented with an admixture of CD5− (likely polyclonal) B cells.

There appeared to be two reasons for failing to meet the purity criterion. The malignant clone from patient CLL062 (Fig. 3B) expressed low levels of CD5, which accounted for the failure to meet the formal purity criterion using CD5 expression. However, actual B-cell purity after RosetteSep isolation was excellent (> 95% B cells, Fig 3B), and no evidence for heterogeneity was seen, although a minor admixture of non-clonal B cells was impossible to exclude by this experiment. Samples from this patient were not purified further. RosetteSep-isolated cells from patient CLL038 (Fig. 3C) were also >95% pure B cells, but there was heterogeneous expression of CD5. The CD5− population in this patient may represent polyclonal non-malignant B cells, accounting for > 5% of the cells. Removal of these cells was accomplished by sorting; the final purity of CD5+CD19+ cells was >98%. In the third patient, CLL063, WBC counts were very low, ranging from 3.5–5.7 × 103/ µl during the study. Presumably due to the smaller number of CLL cells present, > 5% non-B cells were consistently found in the RosetteSep fraction, and all samples from this patient required sorting.

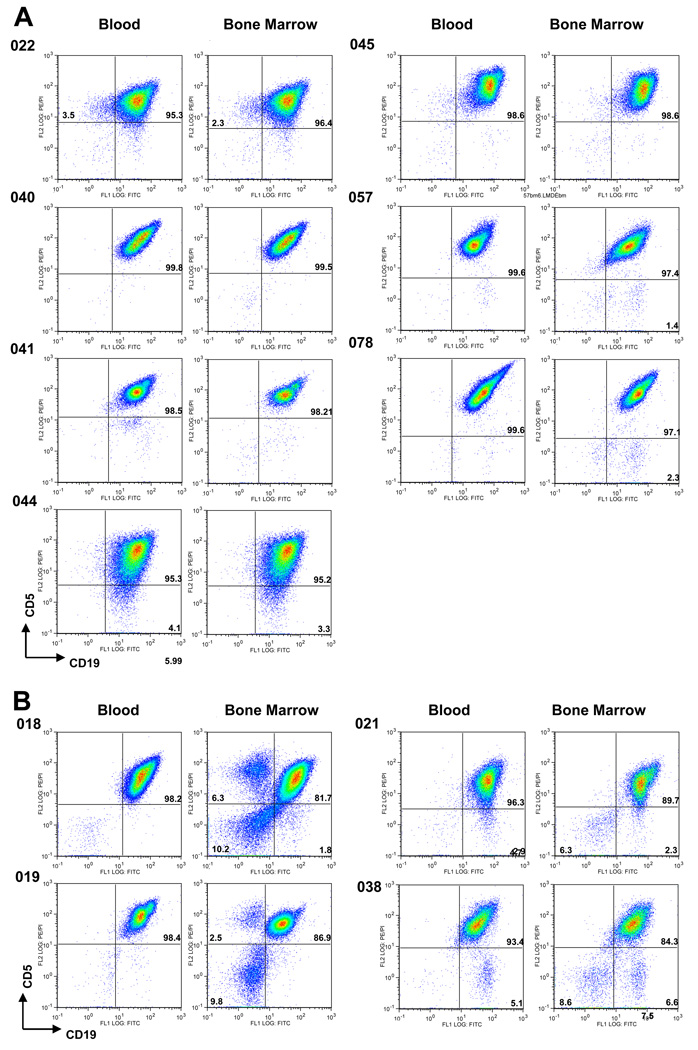

B-CLL cell isolation – purity from bone marrow

We also examined whether the RosetteSep method could be used to isolate CLL cells from BM aspirates. Purity ranged from 84.3% to 99.5%, and the 95% purity cutoff was met or exceeded after RosetteSep isolation from seven of the 11 BM biopsies (64%) (Fig. 4A). For the other four bone marrow preparations (Fig 4 B), flow sorting was used to achieve > 98% purity. There was excellent concordance of CD5/CD19 profiles between blood and bone marrow by FACS analysis regardless of % CD5+/CD19+ purities obtained for these samples (Fig. 4). One of the failed bone marrow samples was from subject CLL 038, in whom > 95% purity was also unobtainable in the blood due to the presence of a presumed non-clonal B cell contaminant (see above). This same contaminant was seen in BM (Fig. 4B). For all failed bone marrow samples, FACS analyses showed non-B cell contamination, which was not typically seen in blood (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Cytometic plots of CLL cells purified from peripheral blood and bone marrow via RosetteSep™ method.

(A) Plots of samples that contained > 95% pure CD5+/CD19 CLL cells in bone marrow. (B) Plots of samples that required further sorting of bone marrow cells due to the presence on non-B cells or non-clonal B cells, or both. FACS analysis shows similar CD5/CD19 profiles for CLL cells purified from either the bone marrow or peripheral blood.

CLL cell isolation - yield

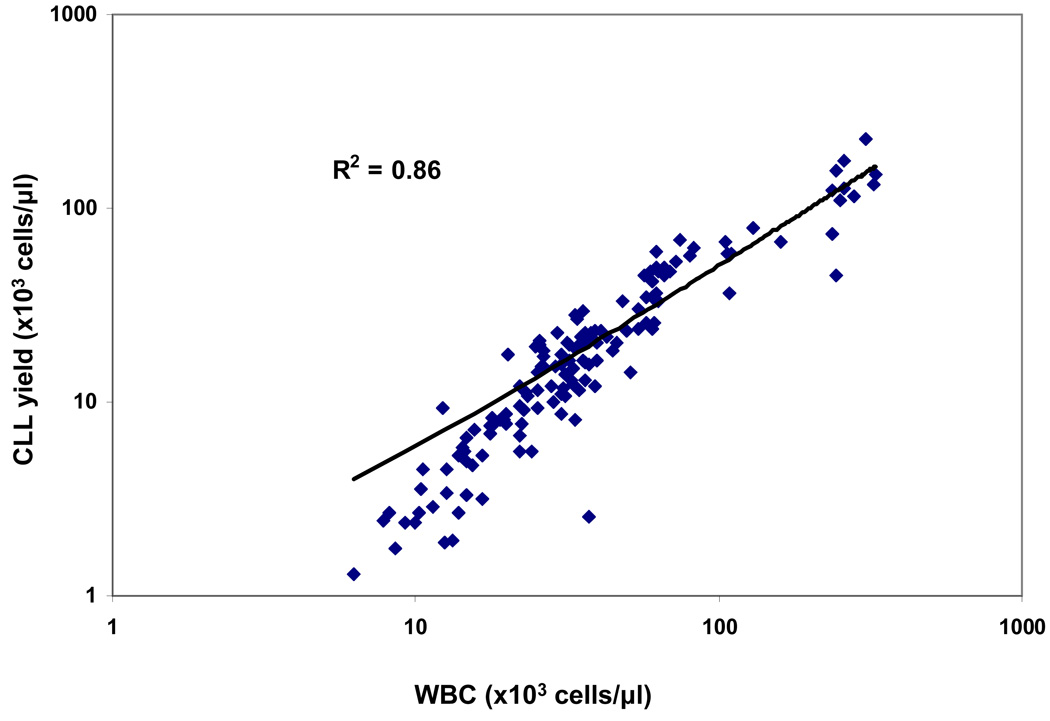

IRMS analysis requires a minimum of 107 cells. Therefore, for a 10 ml sample, yields must be ≥ 1 × 103 cells/ µl of blood. As seen in Fig. 5, cell yields after RosetteSep isolation correlated well with WBC counts (Pearson R = 0.93 for log-transformed data, p < 0.001) and were generally consistent for serial samples obtained from the same patient. Using a mixed effects regression model, the slope of the trend line was 1.23 (CI 1.14–1.31) and thus was significantly steeper than the unity line with slope of 1.00 (P < 0.05). For samples in which sufficient purity was obtained with RosetteSep isolation, cell yields were sufficient to meet IRMS sample requirements with 10 ml sample of blood. This was true even for WBC counts as low as 7.8 × 103 cells/ µl.

Figure 5. Yield of RosetteSep™ versus WBC counts.

The number of CLL cells isolated per ml of blood via RosetteSep™ procedure is plotted against WBC count for each patient visit. The straight line represents a unit slope, corresponding to 100% recovery of all WBC in the RosetteSep isolate; actual yields are systematically lower, particularly in patients with low WBC counts. R = Pearson correlation coefficient, p < 0.001.

CLL Cell Kinetics

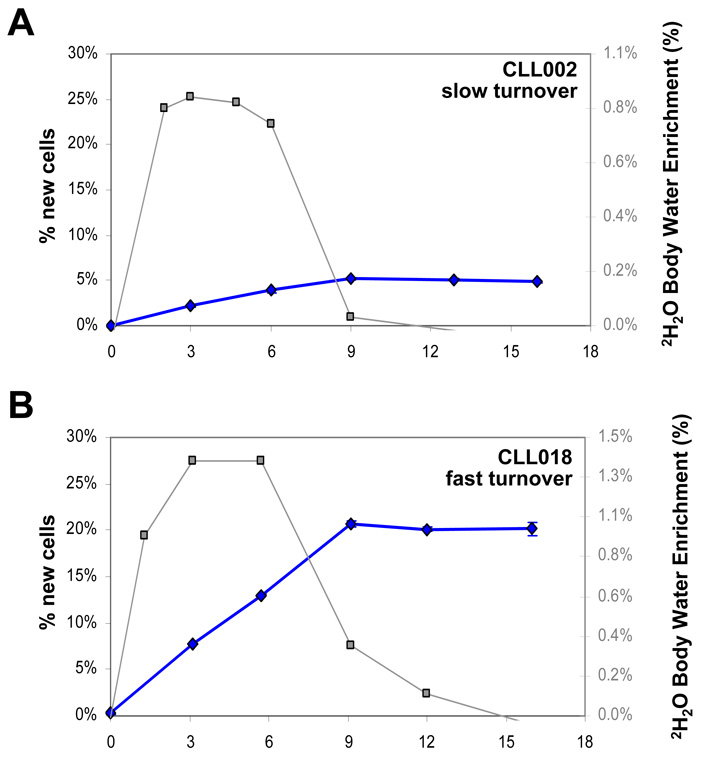

Calculation of the fraction of labeled cells in these experiments requires simultaneous measurement of body water 2H2O enrichment. Average plateau 2H2O body water enrichment was 1.07%, ranging from 0.74% to 1.75%. Enrichments were consistent within a subject, suggesting good compliance with the heavy water ingestion protocol (Fig. 6 and data not shown).

Figure 6. Examples of body water 2H enrichments and CLL cell kinetics in patients.

The time course of total body water 2H enrichment (right axis, squares) and % new cells (left axis, diamonds) is shown for two CLL patients who underwent 2H2O intake and sampling as depicted in Fig. 1. Error bars represent SD of n = 4 replicate analyses. (A) Patient with slow CLL cell birth rate. (B) Patient with fast CLL cell birth rate.

All samples achieving adequate purity by RosetteSep cell isolation were suitable for mass spectrometric analysis of DNA labeling from 2H2O using GC/P/IRMS, with examples from two patients illustrated in Fig. 6. A slow birth rate of CLL cells (0.12% new cells per day, calculated as previously described from peak f (3)) is illustrated in Fig. 6A, while Fig. 6B shows a much more rapid birth rate (0.52% new cells/day). Importantly, using GC/P/IRMS, deuterium enrichment in DNA was observed for all subjects after only 3 weeks of 2H2O exposure, the earliest time point analyzed, despite the significantly decreased heavy water intake and lower body water enrichments, as compared to previous work (3).

Discussion

The ability to measure proliferation in slowly turning over cells in vivo greatly enhances our capacity to understand, determine prognosis, and monitor therapy in indolent malignancies. However, to realize its full potential, this technology must have improved ease of use for patients, providers and researchers alike. We present here a method specifically developed and tested for the determination of CLL cell kinetics. Translation to clinical settings was achieved by processing blood and bone marrow samples at a single site, following overnight shipment from participating clinical centres, using a single-step cell isolation protocol.

Measurement of 2H incorporation into cellular DNA requires isolation of highly purified CLL cells. We had previously shown that a purity of ≥ 95% and rigorous exclusion of contaminating fast-turnover cells, such as monocytes, allowed reliable estimation of 2H2O labelling of DNA in CD4+ T cells (8). Accordingly, our aim was to obtain or exceed this level of purity in CLL samples. The RosetteSep method proved to be highly robust and, when used as a single step, was sufficient for isolation of >95% pure CLL cells from blood approximately 90% of the time. Admixture of non-clonal B cells or non-B cells in approximately 10% of patients may require further separation steps – flow sorting, as in this study, or MACS isolation of CD5+ cells, as used previously (3). Isolation of pure CLL cells from bone marrow with the RosetteSep method resulted in >95% purity in about two thirds of the samples. The lower success rate with BM samples may reflect the lower abundance of erythrocytes or a greater abundance of non-B cells in BM than in blood, resulting in less efficient crosslinking of unwanted cell lineages. Nonetheless, RosetteSep isolation is a useful first purification step for BM aspirates making subsequent purification steps easier and more efficient (e.g. reduced sorter time).

With the use of IRMS technology, we were able to shorten the 2H2O labelling protocol from 12 to 6 weeks. In addition, the amount of initial individual 2H2O doses was also reduced, from 90 ml to 50 ml, thereby eliminating transient vertiginous symptoms associated with 2H2O intake that had been occasionally reported in some patients (2, 3, 10). Using this protocol, enrichments sufficient to calculate accurate CLL cell kinetics were achieved. However, one limitation of this technique is the need for relatively large cell samples (on the order of 107 cells or more (6)), whereas GC/MS analysis is easily performed with 104 cells and may be done on as few as 2000 cells (2). CLL cell yield is directly proportional to WBC count and, in samples that were pure by RosetteSep isolation, we were able to reliably obtain 107 cells from 10 ml of blood with a WBC of 7.8 and above. Lower cell counts may be a problem on several fronts. First, with a low WBC count, there are fewer cells at the start. Second, a smaller proportion of cells will be CLL cells. And finally, as with subject CLL063, when WBCs are very low, RosetteSep is unlikely to result in the required purity. An additional purification step will then further reduce the yield. Therefore, reliable measurement of CLL cell kinetics for patients with WBC counts below 5 × 103 cells/ µl may require additional methodological refinements; recently, we have obtained useful GC/P/IRMS data with as few as 5 × 106 cells.

The protocol presented here represents a simplified, integrated protocol with sensitivity, robustness, a reduced duration of label intake and a less frequent sampling schedule than previously used. The method remains experimental, but has proven feasible outside of sophisticated clinical research centers and may be extendable to other indolent malignancies besides CLL. The simplicity, speed and robustness of CLL cell isolation from blood by the RosetteSep technique may be useful in other applications, as well. A prospective trial using this method to assess the potential use of CLL cell kinetics as a prognostic marker in patients with early stage disease is currently under way and will also allow for comparison of CLL kinetics with other prognostic markers including lymphocyte doubling time, ZAP-70 and CD38 expression, and IgVh mutational status.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Coline McConnel for database implementation and the CLL Research Consortium for supported by the National Cancer Institute (5P01CA081534-10/Thomas Kipps).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R43 CA097686-01A2/EJM and R44-CA097686-01A2/EJM, GH).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Gregory M Hayes, Robert Busch, Jason Voogt, Marc K Hellerstein, Nicholas Chiorazzi, and Elizabeth J Murphy have either shares or options in KineMed Inc.

Contributions:

GMH and RB share co-first-authorship of this paper based upon equal efforts and along with EJM performed data analysis and manuscript writing. GMH, RB, EJM, JV, IMS, and TAG generated the scientific data. MKH, NC, and KRR provided scientific leadership and expertise to ensure success of this work in addition to editing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Chiorazzi N. Cell proliferation and death: forgotten features of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2007 Sep;20(3):399–413. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Busch R, Neese RA, Awada M, Hayes GM, Hellerstein MK. Measurement of cell proliferation by heavy water labeling. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(12):3045–3057. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Messmer BT, Messmer D, Allen SL, Kolitz JE, Kudalkar P, Cesar D, Murphy EJ, Koduru P, Ferrarini M, Zupo S, Cutrona G, Damle RN, Wasil T, Rai KR, Hellerstein MK, Chiorazzi N. In vivo measurements document the dynamic cellular kinetics of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. J Clin Invest. 2005 Mar;115(3):755–764. doi: 10.1172/JCI23409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Defoiche J, Debacq C, Asquith B, Zhang Y, Burny A, Bron D, Lagneaux L, Macallan D, Willems Lc. Reduction of B cell turnover in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2008 Oct;143(2):240–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Gent R, Kater AP, Otto SA, Jaspers A, Borghans JA, Vrisekoop N, Ackermans MA, Ruiter AF, Wittebol S, Eldering E, van Oers MH, Tesselaar K, Kersten MJ, Miedema F. In vivo dynamics of stable chronic lymphocytic leukemia inversely correlate with somatic hypermutation levels and suggest no major leukemic turnover in bone marrow. Cancer Res. 2008 Dec 15;68(24):10137–10144. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voogt JN, Awada M, Murphy EJ, Hayes GM, Busch R, Hellerstein MK. Measurement of very low rates of cell proliferation by heavy water labeling of DNA and gas chromatography/pyrolysis/isotope ratio-mass spectrometric analysis. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(12):3058–3062. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Grever M, Kay N, Keating MJ, O'Brien S, Rai KR. National Cancer Institute-sponsored Working Group guidelines for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: revised guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 1996 Jun 15;87(12):4990–4997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busch R, Cesar D, Higuera-Alhino D, Gee T, Hellerstein MK, McCune JM. Isolation of peripheral blood CD4(+) T cells using RosetteSep and MACS for studies of DNA turnover by deuterium labeling. J Immunol Methods. 2004 Mar;286(1–2):97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen JL, Peacock E, Samady W, Turner SM, Neese RA, Hellerstein MK, Murphy EJ. Physiologic and pharmacologic factors influencing glyceroneogenic contribution to triacylglyceride glycerol measured by mass isotopomer distribution analysis. J Biol Chem. 2005 Jul 8;280(27):25396–25402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413948200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neese RA, Misell LM, Turner S, Chu A, Kim J, Cesar D, Hoh R, Antelo F, Strawford A, McCune JM, Christiansen M, Hellerstein MK. Measurement in vivo of proliferation rates of slow turnover cells by 2H2O labeling of the deoxyribose moiety of DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Nov 26;99(24):15345–15350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232551499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]