Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The objective of the study is to evaluate low-dose aspirin (LDA) for pre-eclampsia prevention in twin gestations with elevated maternal serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).

STUDY DESIGN

Secondary analysis of the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units High-Risk Aspirin trial for pre-eclampsia prevention. A threshold hCG level for predicting pre-eclampsia was identified in placebo-randomized patients. Pre-eclampsia incidence and time of onset were compared between treatment groups, overall and by hCG threshold category.

RESULTS

Pre-eclampsia incidence was lower with LDA than with placebo (6% vs 16%, OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.82). An hCG threshold of 29.96 IU ml−1 best predicted pre-eclampsia. In patients with hCG <29.96 IU ml −1, the differences in pre-eclampsia incidence or time of onset were not significant. In patients with hCG >29.96 IU ml −1, LDA was associated with lower pre-eclampsia incidence than placebo (6% vs 23%, OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.79) and delayed onset.

CONCLUSION

Twin gestations with elevated hCG levels may benefit from LDA for pre-eclampsia prevention.

INTRODUCTION

Pre-eclampsia and its associated morbidity and mortality remain major public health concerns worldwide.1,2 While large meta-analyses and systematic reviews have consistently shown low-dose aspirin (LDA) to be effective in reducing the incidence of pre-eclampsia,3–7 the benefits are generally modest and ideal candidates to receive LDA are not well-defined. The latter limitation results from many ‘high-risk’ studies using heterogeneous inclusion criteria, which hampers translation into clinical practice. In the United States, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that LDA use be limited to women with a history of either recurrent pre-eclampsia or severe disease requiring delivery prior to 34 weeks.8 Such restricted indications will likely result in minimal effects on the overall adverse health consequences of pre-eclampsia. Other public health publications recommend LDA prophylaxis for all women with twin gestations.5,9 Accordingly, clarification of LDA’s benefits in women with twin gestations is needed.

In our recent study,10 elevated levels of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) were shown to be strongly associated with the development of pre-eclampsia in women with multiple gestations. This finding has been seen before in several studies showing the association of increased hCG with pre-eclampsia and other adverse perinatal outcomes.11–15 Here we investigate the ability of LDA to reduce the incidence of pre-eclampsia in women with twin gestations and an elevated hCG.

METHODS

This study is a secondary analysis of the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network High Risk Aspirin (HRA) double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial of LDA to prevent pre-eclampsia in women at increased risk.16 In the HRA trial, women were enrolled between 12 and 26 weeks gestational age with at least one risk factor for pre-eclampsia (multiple gestation, chronic hypertension, insulin-dependent diabetes or pre-eclampsia in a prior pregnancy) at 13 centers from 1991 to 1995. Randomization to LDA or placebo occurred shortly after enrollment. Full details of patient inclusion, diagnostic and clinical criteria for the high-risk patient groups, the diagnosis of pre-eclampsia and randomization have been previously published.16 Of note, women with multiple gestations were not eligible for the HRA trial if they also had diagnoses of diabetes mellitus, chronic hypertension or proteinuria.16 After the HRA trial began enrolling, an ancillary study was started with collection of maternal blood samples at some sites to create a repository for future studies. A panel of serum biomarkers associated with pre-eclampsia, selected by the original study investigators, were collected shortly after enrollment in a subset of patients using methods that have been previously published.17–19 The institutional review boards at each of the sites approved the original MFMU study, and the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board considered this secondary analysis to be non-human subjects research given the complete de-identification of the data and therefore exempt.

For the current study, women were excluded if serum hCG levels were not available, if the multiple gestations were greater than twins or if the primary outcome of pre-eclampsia was missing. To confirm the success of randomization within this subgroup for our analysis, the demographics of the aspirin- and placebo-randomized women were summarized using frequency and percent for categorical variables, and mean with standard error (s.e.) for continuous variables. Skewed measures were analyzed on the log scale and reported as geometric mean and 95% confidence interval (g95% CI). Differences in the aspirin- and placebo-randomized groups among our cohort of women were tested for statistical significance with χ2 for categorical measures or two-sample t-test for continuous measures without assumption of equal variance. The demographics of our cohort were also compared with all of the women with multiple gestations in the original MFMU HRA trial cohort who were excluded from our analyses using the same statistical methods to ensure that there was not a selection bias introduced by the availability of hCG levels in only a subset of the women.

To define ‘elevated hCG’ for the purposes of this analysis, we estimated the probability of pre-eclampsia in a logistic regression model among placebo-randomized patients. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve methods were used to determine a potential hCG threshold (balancing sensitivity and specificity) for the development of pre-eclampsia. Area under the curve from the ROC and sensitivity and specificity of the threshold with 95% CI are reported.

The rate of pre-eclampsia was then compared between women who randomized to LDA and those randomized to placebo overall in our full cohort, and separately among the two mutually exclusive groups of women with an hCG below the ROC-derived threshold and women with an hCG above the ROC-derived threshold. Logistic regression modeling was used to determine if LDA was associated with a lower odds of developing pre-eclampsia in women with twins and elevated hCG (above the ROC-established threshold). A sensitivity analysis was also performed with body mass index (BMI) as a covariate in the logistic model, given the potential effect of BMI on serum hCG levels. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% CI are reported. Kaplan–Meier estimates of time to onset of pre-eclampsia were compared between groups using a log-rank test. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

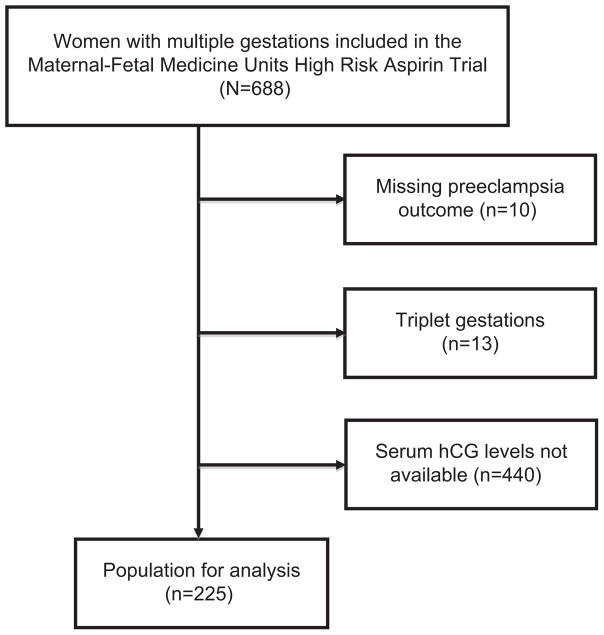

The HRA trial included 688 women with multiple gestations of which 248 had hCG levels available. After other exclusion criteria were applied, complete data were available for 225 women (Figure 1). Among these 225 women, 47% (n = 106) were randomized to LDA and 53% (n = 119) to placebo at a mean gestational age of 21.7 weeks gestation (Table 1). Full participant demographics are displayed in Table 1. There were no clinically or statistically significant differences between treatment groups in maternal age, race or parity. Additionally, there were no significant demographic differences between our secondary analysis study population and the women excluded from our analysis but investigated in the HRA trial16 (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study subjects.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic characteristics by the treatment group

| Characteristics | Overall

|

Treatment group

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 225 | LDA (N = 106) | Placebo (N = 119) | P-valuea | |

| Maternal ageb (years) | 25.1 (0.39) | 25.0 (0.52) | 25.2 (0.57) | 0.840 |

| Predominant race,c n (%) | 0.647 | |||

| African American | 109 (48) | 53 (50) | 56 (47) | |

| White | 79 (35) | 37 (35) | 42 (35) | |

| Hispanic | 36 (16) | 15 (14) | 21 (18) | |

| Other | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Parity,c,d n (%) | 0.214 | |||

| 0 | 88 (39) | 46 (43) | 42 (35) | |

| 1 or more | 137 (61) | 60 (57) | 77 (65) | |

| BMI (kg m−2)e | 25.7 (24.9, 26.5) | 25.3 (24.2, 26.5) | 26.1 (25.0, 27.2) | 0.379 |

| GA, randomizationb (w) | 21.7 (0.23) | 22.1 (0.31) | 21.5 (0.33) | 0.211 |

| GA, deliveryb (w) | 34.6 (0.23) | 34.6 (0.32) | 34.6 (0.31) | 0.983 |

| Birth weightb (g) | 2179 (41.5) | 2154 (60.0) | 2202 (57.6) | 0.563 |

| SGA,c,f n (%) | 17 (8) | 11 (10) | 6 (5) | 0.131 |

| Pre-eclampsia,c n (%) | 25 (11) | 6 (6) | 19 (16) | 0.014 |

| GA, onset of pre-eclampsiab,g (w) | 34.5 (0.4) | 33.8 (0.8) | 34.7 (0.5) | 0.392 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; GA, gestational age; LDA, low-dose aspirin; SGA, small for GA; w, weeks.

P-values are from χ2 for categorical measures or two-sample t-test for continuous measures.

Mean (s.e.).

n (%) of respective column N.

Parity is defined as the number of deliveries past 20 weeks gestational age.

Geometric mean (95% CI).

SGA is defined as birth weight below the 10th percentile of normative birth weight for twins.

GA for onset of pre-eclampsia only applies to women diagnosed with pre-eclampsia, the N in the line directly above.

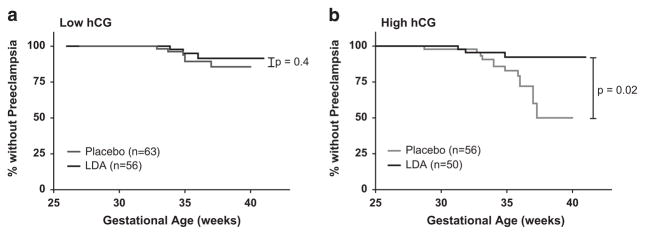

Among placebo-randomized women, ROC methodology was used to determine an hCG threshold for predicting the development of pre-eclampsia (Figure 2). The estimated ROC curve had an area under the curve of 0.61 (95% CI 0.479 to 0.743). An hCG threshold of 29.96 IU ml −1 was identified to balance both sensitivity and specificity. The sensitivity was 0.68 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.87) and specificity was 0.55 (95% CI 0.45 to 0.65) for predicting the development of pre-eclampsia. Of 225 women, 106 (47%) had an hCG above this threshold. For reference, an hCG level of 29.96 IU ml −1 corresponds to ~ 1.86 multiples of the median at 19.6 weeks, the mean gestational age for serum drawn as part of the original study.10,17–19

Figure 2.

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis for the development of pre-eclampsia among placebo-randomized women with twin gestations in relation to human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) biomarker levels.

Women determined to have a ‘high hCG’ had a lower body mass index (BMI, 24.4 vs 27.0 kg m −2, P<0.001), a lower GA at randomization (20.7 vs 22.7 weeks, P<0.001), a lower GA at delivery (33.9 vs 35.2 weeks, P = 0.003) and a lower combined birth weight (2030 vs 2312 g, P<0.001) when compared with women determined to have a ‘low hCG’ (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of demographic characteristics by hCG level

| Characteristics | Overall

|

hCG level

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 225 | Higha (N = 106) | Lowa (N = 119) | P-valueb | |

| Maternal agec (years) | 25.1 (0.39) | 25.3 (0.62) | 25.1 (0.48) | 0.711 |

| Predominant race,d n (%) | 0.687 | |||

| African American | 109 (48) | 49 (46) | 60 (50) | |

| White | 79 (35) | 38 (36) | 41 (34) | |

| Hispanic | 36 (16) | 18 (15) | 18 (15) | |

| Other | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Parity,d,e n (%) | 0.487 | |||

| 0 | 88 (39) | 44 (42) | 44 (37) | |

| 1 or more | 137 (61) | 62 (58) | 75 (63) | |

| BMI (kg m−2)f | 25.7 (24.9, 26.5) | 24.4 (23.5, 25.3) | 27.0 (25.8, 28.3) | <0.001 |

| GA, randomizationc (w) | 21.7 (0.23) | 20.7 (0.36) | 22.7 (0.26) | <0.001 |

| GA, deliveryc (w) | 34.6 (0.23) | 33.9 (0.36) | 35.2 (0.27) | 0.003 |

| Birth weightc (g) | 2179 (41.5) | 2030 (60.5) | 2312 (54.5) | <0.001 |

| SGA,d,g n (%) | 17 (8) | 10 (9) | 7 (6) | 0.314 |

| Pre-eclampsia,d n (%) | 25 (11) | 16 (15) | 9 (8) | 0.073 |

| GA, onset of pre-eclampsiac,h (w) | 34.5 (0.4) | 34.2 (0.6) | 34.8 (0.4) | 0.429 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; GA, gestational age; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; SGA, small for GA; w, weeks.

Low or high human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) designations are in respect to the determined threshold of 29.96 IU ml−1.

P-values from χ2 for categorical measures or two-sample t-test for continuous measures.

Mean (s.e.).

n (%) of respective column N.

Parity is defined as the number of deliveries past 20 weeks gestational age.

Geometric mean (95% CI).

SGA is defined as birth weight below the 10th percentile of normative birth weight for twins.

GA for onset of pre-eclampsia only applies to women diagnosed with pre-eclampsia, the N in the line directly above.

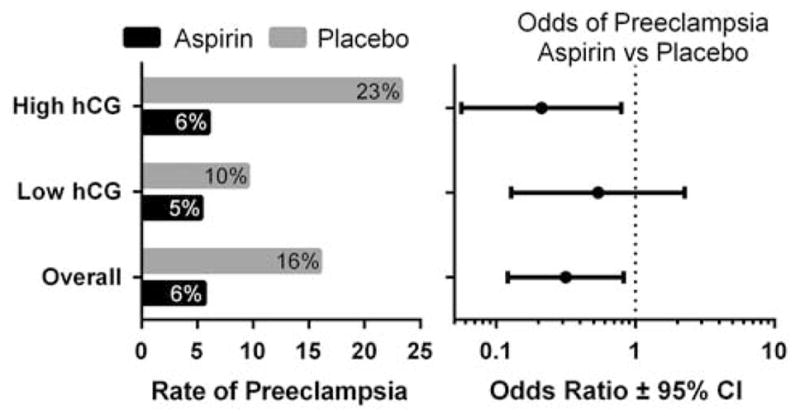

The overall incidence of pre-eclampsia in women with twin gestations was 11% (25 of 225); 6% (6 of 106) in the LDA treatment group and 16% (19 of 119) in women receiving placebo (OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.82) (Table 1 and Figure 3). There were no clinically or statistically significant differences in patient demographics between the women excluded from the original study cohort (n = 453) and the 225 women included in this analysis, including gestational age at randomization (21.4 (s.e.: 0.17), 21.7 (0.23), P = 0.27; other comparisons for maternal age, race, parity, BMI, GA at delivery and pre-eclampsia not shown).

Figure 3.

Low-dose aspirin (LDA) treatment was associated with a decreased rate of pre-eclampsia among women with twin gestations (left panel). Odds ratios (OR) for pre-eclampsia with LDA vs placebo treatment are shown with 95% confidence intervals (CI, right panel). Low or high human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) designations are in respect to the determined threshold of 29.96 IU ml−1.

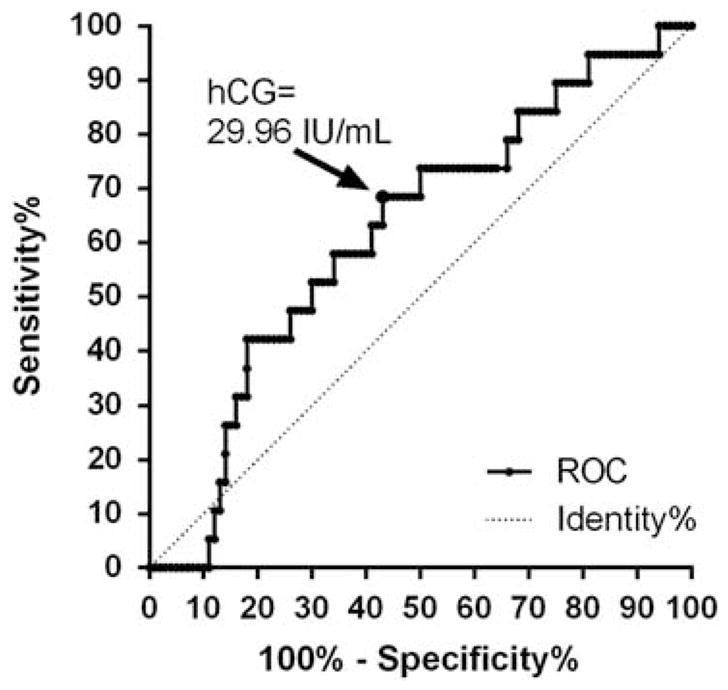

In the 119 women (53%) with serum hCG levels below the threshold of 29.96 IU ml−1, the overall incidence of pre-eclampsia was 8% (9 of 119). In these women with low hCG, 56 received LDA treatment and 63 received placebo. The difference in pre-eclampsia incidence between treatment groups when the hCG was below this delineated threshold was not statistically significant (5% in the LDA group vs 10% in the placebo group (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.13 to 2.26) (Figure 3)). There was no significant difference in the time to onset of pre-eclampsia between treatment groups in women with low hCG (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier plots of time to pre-eclampsia onset by human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) status and treatment group. Low-dose aspirin (LDA) treatment did not influence time to pre-eclampsia onset in women with low hCG (a, P = 0.4). However in women with high hCG, there was a significant difference in time to pre-eclampsia onset with LDA treatment (b, P =0.02). Curves were censored at birth if pre-eclampsia did not occur. Low or high hCG designations are in respect to the previously determined threshold of 29.96 IU ml −1.

In the 106 women (47%) with serum hCG levels above the threshold, 50 received LDA treatment and 56 received placebo. The overall incidence of pre-eclampsia in the high hCG group was 15% (16 of 106). Treatment with LDA in this group was associated with a significantly lower incidence of pre-eclampsia: 6% (3 of 50) in women receiving LDA vs 23% (13 of 56) in those receiving placebo (OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.79) (Figure 2). There was a significant increase in the time to onset of pre-eclampsia in women treated with LDA vs placebo (Figure 4, P = 0.02).

When adjusted for BMI, results for low and high hCG groups remained similar in magnitude and significance (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We show in a secondary analysis of data from a randomized-controlled trial that LDA reduced the incidence of pre-eclampsia in women with twin gestations, and this result was most striking in women with elevated hCG levels. Importantly, in the elevated hCG group, the onset of pre-eclampsia was also delayed. These results may help identify a specific group of women that can benefit from LDA for pre-eclampsia prevention.

For over 30 years, LDA has been studied intensively as a strategy to prevent pre-eclampsia. Multiple studies, summarized in meta-analyses and systematic reviews,3–7 have shown significant reductions in pre-eclampsia incidence especially in women at high risk. However, difficulties in defining clear indications for LDA have limited widespread integration into clinical practice.16,20 In fact, the recommendations of multiple professional organizations vary regarding the use of LDA to prevent pre-eclampsia. A twin pregnancy without other risk factors meets criteria for initiation of LDA prophylaxis per the United States Preventative Services Task Force5 and World Health Organization9 criteria but not by ACOG guidelines that are based on prior pregnancy outcomes.8

In a previous analysis, we demonstrated differences in early pregnancy biomarkers in women with diverse pre-eclampsia risk factors. Several groups including ours have suggested that pre-eclampsia may be a final common syndrome with heterogeneous pathophysiologic etiologies that are dependent on specific risk factors.10,21 Accordingly, LDA might be effective pre-eclampsia prophylaxis in some high-risk groups and not in others.

Here, we chose to study the effect of LDA in women with a twin gestation and elevated hCG. Elevated hCG at the time of second trimester maternal serum screening in singletons has been reported by numerous authors to be associated with the later development of pre-eclampsia.11–15 This finding has also been shown in the first trimester.22 Our previous report extended this association to twin pregnancies as well.10 Moreover, work by Wenstrom et al.23 suggests that pregnancies with elevated mid-trimester levels of hCG might benefit from LDA. In that study, use of LDA was associated with an increase in birth weight and a nonsignificant trend for a reduction in pre-eclampsia. Together, these observations suggest twins with elevated hCG as a natural population in which to investigate the possible benefits of LDA.

The incidence of pre-eclampsia with LDA treatment in this study is notably different from that reported for multiple gestations in the original MFMU HRA trial.16 Our cohort had a 6% rate of pre-eclampsia in the LDA group and 16% in the placebo group (P = 0.018) vs a nonsignificant difference of 12 and 16%, respectively, in the original study.16 We investigated possible explanations for this discrepancy. There were no significant demographic differences between our study population and the women who were excluded from our analysis but included in the original paper of Caritis et al. (data not shown). As such, it is not clear why LDA treatment had a more substantial effect in women who had serum hCG levels drawn in the original trial and available for analysis, but this difference cannot be explained by demographics or age at randomization.

It is important to note that nearly half of the twin gestations studied (47%) had an ‘elevated’ level of hCG as determined by ROC analysis, and therefore might benefit from LDA. Furthermore, hCG is a widely available test that could be easily incorporated into further pre-eclampsia prevention strategies. It is not clear from these data however if the hCG threshold should be set at an absolute or a gestational-age specific cutoff.

Some groups suggest that earlier initiation of LDA treatment (<16 weeks gestation) may have greater benefits.6 In the current study, the average gestational age at randomization was 21.7 weeks with initiation of LDA or placebo shortly thereafter. As seen in Table 2, the high hCG group did have a lower gestational age at randomization (mean 20.7, s.e. 0.36). It is not clear if this group had higher hCG levels due to the earlier gestational age at randomization and serum sampling or the individual characteristics of the pregnancies. However, in data not shown, a downward trend of hCG with increasing gestational age that leveled off near 18 weeks gestation was observed, prior to the mean age of sampling in all groups. Here we show a positive effect of LDA treatment despite initiation of treatment greater than 20 weeks gestation, consistent with other reviews that did not find a differential effect with treatment if started after 16 weeks gestation.3,7 However, it is possible that if serum hCG data were available for additional women, a differential treatment effect based on the timing of LDA treatment initiation may have become apparent.

The strengths of this study are the prospective data collection that occurred at the time of the original trial by trained research nurses. The cohort is large and diverse, and pre-eclampsia was the primary outcome of the original trial. A limitation of the current study is that certain data were not available for consideration, such as chorionicity of the twin pregnancies included (a variable not recorded in the original data set) and the number of multifetal pregnancies without serum hCG levels available for analysis. It is less likely that these excluded cases introduce a significant bias as there were no significant demographic differences between the women with and without serum hCG data available, though this possibility cannot be fully excluded.

A further limitation of our study is that the ROC curve for hCG as a predictor of pre-eclampsia demonstrated only modest predictive capability with an area under the curve of 0.61. However, we are not proposing this threshold as a screening test to predict pre-eclampsia per se, but rather to identify a subset of women that might benefit from LDA, and in this regard it is successful in this cohort. As the use of LDA for pre-eclampsia prevention has not been associated with significant adverse events,5,16 wide use of this treatment may be possible even in the setting of a modest predictive association.

While we detected a difference in the incidence of pre-eclampsia in our high hCG group and not our low hCG group, there is a possibility that we simply had an inadequate sample size to detect a difference in the incidence of pre-eclampsia in the group of women with a low hCG level. We performed a post hoc sample size calculation and determined that in order to detect a significant difference (α: 0.05; β: 0.80) in the incidence of pre-eclampsia between groups of 4% as was observed in this low hCG group, we would need to randomize 1542 women to either LDA or placebo.

The use of elevated second trimester serum hCG in twin pregnancies represents an appealing approach for pre-eclampsia prevention based on the easy availability of hCG levels and the high percentage of women with elevated levels that could benefit from treatment. However, as a secondary analysis, these data should be used to motivate clinical trials, not change current clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the assistance of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network in making the database from the MFMU High-Risk Aspirin trial available for secondary analysis. The contents of this report represent the views of the authors and do not represent the views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

These findings of this study were presented at the 62nd Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society for Reproductive Investigation, 25 to 28 March 2015, in San Francisco, CA.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. [accessed 5 October 2015];The World Health Report 2005: Make Every Mother and Child Count. 2005 Available at http://www.who.int/whr/2005/whr2005_en.pdf.

- 2.Duley L. The global impact of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Semin Perinatol. 2009;33:130–137. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Askie L, Duley L, Henderson-Smart D, Stewart L Paris Collaborative Group. Anti-platelet agents for prevention of pre-eclampsia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. 2005;369:1791–1798. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60712-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coomarasamy A, Honest H, Papaioannou S, Gee H, Khan K. Aspirin for prevention of preeclampsia in women with historical risk factors: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:1319–1332. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lefevre M U.S. Preventative Services Task Force. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:819–826. doi: 10.7326/M14-1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bujold E, Roberge S, Lacasse Y, Bureau M, Audibert F, Marcoux S, et al. Prevention of preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction with aspirin started in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:402–414. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e9322a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henderson J, Whitlock E, O’Connor E, Senger C, Thompson J, Rowland M. Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:695–703. doi: 10.7326/M13-2844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1122–1131. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000437382.03963.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. [accessed 5 October 2015];WHO Recommendations for Prevention and Treatment of Pre-eclampsia and Eclampsia. 2011 Available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241548335_eng.pdf. [PubMed]

- 10.Metz T, Allshouse A, Euser A, Heyborne K. Preeclampsia in high risk women is characterized by risk group-specific abnormalities in serum biomarkers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:512, e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsen R, Woelkers D, Dunsmoor-Su R, LaCoursiere Y. Abnormal second-trimester serum analytes are more predictive of preterm preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:228, e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dugoff L, Hobbins JC, Malone FD, Vidaver J, Sullivan L, Canick JA, et al. Quad screen as a predictor of adverse pregnancy outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:260–267. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000172419.37410.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandra S, Scott H, Dodds L, Watts C, Blight C, Van den Hof M. Unexplained elevated maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein and/or human chorionic gonadotropin and the risk of adverse outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:775–781. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00769-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benn PA, Horne D, Briganti S, Rodis JF, Clive JM. Elevated second-trimester maternal serum hCG alone or in combination with elevated alpha-fetoprotein. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:217–222. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorenson TK, Williams MA, Zingheim RW, Clement SJ, Hickok DE. Elevated second-trimester human chorionic gonadotropin and subsequent pregnancy-induced hypertension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:834–838. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caritis S, Sibai B, Hauth J, Lindheimer MD, Klebanoff M, Thom E, et al. Low-dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia in women at high risk. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:701–705. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803123381101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powers RW, Jeyabalan A, Clifton RG, Van Dorsten P, Hauth JC, Klebanoff MA, et al. Soluble fms-Like Tyrosine Kinase 1 (sFlt1), Endoglin and Placental Growth Factor (PlGF) in preeclampsia among high risk pregnancies. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sibai B, Romero R, Klebanoff M, Rice MM, Caritis S, Lindheimer MD, et al. Maternal plasma concentrations of the soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 are increased prior to the diagnosis of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:e1–630. e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hauth J, Sibai B, Caritis S, Vandorsten P, Klebanoff M, Macpherson C, et al. Maternal serum thromboxane B2 concentrations do not predict improved outcomes in high-risk pregnancies in a low-dose aspirin trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1193–1199. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sibai BM. Prevention of preeclampsia: a big disappointment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1275–1278. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maynard S, Crawford S, Bathgate S, Yan J, Robidoux L, Moore M, et al. Gestational angiogenic biomarker patterns in high risk preeclampsia groups. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:53, e1–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Lorenzo G, Ceccarello M, Cecotti V, Ronfani L, Monasta L, Vecchi Brumatti L, et al. First trimester maternal serum PlGF, free beta-hCG, PAPP-A, PP-13, uterine artery Doppler and maternal history for the prediction of preeclampsia. Placenta. 2012;33:495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wenstrom KD, Hauth JC, Goldenberg RL, Dubard MB, Lea C. The effect of low-dose aspirin on pregnancies complicated by elevated human chorionic gonadotropin levels. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1292–1296. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)91373-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]