Abstract

Several proteins are found misfolded and aggregated in sporadic and genetic forms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). These include superoxide dismutase (SOD1), transactive response DNA-binding protein (TDP-43), fused in sarcoma/translocated in liposarcoma protein (FUS/TLS), p62, vasolin-containing protein (VCP), Ubiquilin-2 and dipeptide repeats produced by unconventional RAN-translation of the GGGGCC expansion in C9ORF72. Up to date, functional studies have not yet revealed a common mechanism for the formation of such diverse protein inclusions. Consolidated studies have demonstrated a fundamental role of cysteine residues in the aggregation process of SOD1 and TDP43, but disturbance of protein thiols homeostatic factors such as protein disulfide isomerases (PDI), glutathione, cysteine oxidation or palmitoylation might contribute to a general aberration of cysteine residues proteostasis in ALS. In this article we review the evidence that cysteine modifications may have a central role in many, if not all, forms of this disease.

Keywords: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, cysteine, neurodegeneration, protein aggregation, superoxide dismutase 1, TDP43

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is an adult-onset fatal neurodegenerative disease characterized by fast progressing degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons of the motor cortex, brainstem and spinal cord. Motor neuron degeneration is associated with muscle weakness and atrophy followed by paralysis until death by respiratory failure (Robberecht and Philips, 2013). Although ALS is sporadic in the majority of cases (sporadic ALS, sALS), this disease is inherited genetically in a significant part of patients (familial ALS, fALS). ALS-associated genes code for proteins involved in diverse cellular processes, and diverse mechanisms have been proposed as major contributors to neurodegeneration in fALS and sALS (Renton et al., 2014). These include defective RNA metabolism, glutamate excitotoxicity, disruption of membrane trafficking, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and protein misfolding and aggregation (Peters et al., 2015). The variety of these factors makes the etiology of the disease extremely complex, a fact that is reflected in the current unavailability of effective therapy.

A common feature observed in patients, regardless their classification as sporadic or familial, is the presence of motor neuronal inclusions, formed by misfolded aggregated proteins, which are associated with synaptic loss and neuronal death (Sasaki and Maruyama, 1994; Robberecht and Philips, 2013). In particular, patients carrying mutations in the genes coding for the antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), for the RNA-binding proteins transactive response DNA-binding protein (TDP43) and fused in sarcoma/translocated in liposarcoma protein (FUS/TLS) or an expanded hexanucleotide GGGGCC in the C9orf72 gene have proteinaceous inclusions made of, respectively, SOD1, TDP43, FUS and dipeptide repeats originating from RAN translation of the exanucleotide. Interestingly, TDP43 is found aggregated also in sALS and in non-TDP43 fALS patients, with the exception of those with SOD1 mutations (Lee et al., 2011).

In this article we review current evidence supporting the idea that ALS can be seen as a cysteninopathia following an incorrect redox state of cysteine residues.

Cysteines in Oxidative Folding and in Cellular Redox Balance

Protein cysteine residues contain a thiol group that can form covalent disulfide bridges during the process of oxidative folding and thus are critical for correct protein structure, function and stability (Feige and Hendershot, 2011). In eukaryotic cells, stable intra-molecular or inter-molecular disulfide bridges are often formed in exported proteins in the oxidizing environment of the ER lumen (Walter and Ron, 2011; Oka and Bulleid, 2013) through reactions catalyzed by the family of protein disulfide isomerases (PDI; see below) or in the mitochondrial intermembrane space (IMS) for those proteins imported in this organelle through the MIA pathway (Mordas and Tokatlidis, 2015; Chatzi et al., 2016). Disulfide bridges exist also in cytosolic proteins, and chaperones such as the heat shock proteins Hps70 and Hps90 seem to be able to catalyze the formation of disulfide bonds and possess foldase activity in the more reducing cytosolic environment as well (Chambers and Marciniak, 2014).

Besides their role in disulfide bridging, cysteine residues also play a main role in maintaining a correct cellular redox balance. First, the cysteine residue of the tripeptide glutathione (GSH, γ-L-Glutamyl-L-cysteinylglycine) participates in a complex network of enzyme-catalized reactions (Meister, 1988). Glutathione is the major thiol antioxidant in mammalian cells and reduces disulfide bonds formed within cytoplasmic proteins by serving as an electron donor. In the process, glutathione is converted to its oxidized form, glutathione disulfide (GSSG), which can be reduced back by glutathione reductase, using NADPH as an electron donor. GSH serves as a cofactor for a number of antioxidant enzymes (such as glutathione reductases, glutathione peroxidases, glutathione S-transferases) that collectively collaborate to maintain a correct intracellular redox state and thus the ratio of reduced glutathione to GSSG within cells is often used as a measure of cellular oxidative stress (Meister, 1988).

Second, it is well known that redox-sensitive cysteine thiols are critical for signal transduction, transcription factor binding to DNA (e.g., Nrf-2, NF-κB), receptors activation and other processes (Jones, 2008). A clear overlap exists between signal transduction and redox biology, since the activity of enzymes in different pathways and transcription factors that work as redox sensors is based on disulfide bond formation, a mechanism that is often used to trigger and to maintain redox homeostasis (Forman, 2016).

Cysteine-Dependent Aggregation and Mislocalization of ALS Proteins

Oxidative stress, that has been widely described in tissues obtained from ALS patients and transgenic mouse models (Cozzolino et al., 2008; Barber and Shaw, 2010), arises in conditions of unbalanced increase of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), which in turn may change the conformation of proteins and lead to the formation of aggregates and protein inclusions (Li et al., 2013). In the last 10 years, oxidation dependent, cysteine-mediated protein aggregation has been extensively demonstrated for mutant and wild-type SOD1 and TDP43.

Human homodimeric wild type SOD1 has four cysteine residues; two of them (Cys57 and Cys146) form an intra-monomer disulfide bridge, while Cys6 and Cys111 are un-bridged, with Cys111 relatively exposed on the protein surface near the dimer interface. The mechanism of mutant SOD1 aggregation involves oligomerization that may be the consequence of covalent disulfide cross-linking mediated mainly by Cys111 (Cozzolino et al., 2008). The Cys6 residue, which is packed tightly within the interior of the β-barrel, may play a role as well (Niwa et al., 2007), although all four Cys residues are mutated, and thus not present, in some patients1, which would argue against a direct role of Cys-mediated aggregation in the pathogenesis of ALS. On this line, data obtained in models in vitro and in vivo indicate that soluble forms of mutant SOD1 initiate disease and larger aggregates are implicated only in rapidly progressing events in the final stages of disease, and thus it has been argued that disulfide bond formation is a secondary effect and not primarily causative for aggregate formation in ALS (Karch et al., 2009). However, that article did not consider that uncontrolled accumulation of (aggregated) mutant SOD1 inside the mitochondria of cells may be directly responsible for mitochondrial impairment observed in ALS models and patients (Wiedemann et al., 2002; Ferri et al., 2006). Interestingly, cysteine residues are also involved in SOD1 localization in the IMS (Cozzolino et al., 2009; Kawamata and Manfredi, 2010). SOD1 import in IMS also involves its copper chaperone that acts in a redox-dependent manner, promoting SOD1 maturation through formation of disulfide bridges and its retention in this cellular compartment (Banci et al., 2008; Kawamata and Manfredi, 2010). Thus control of the redox state of cysteine residues and SOD1 aggregation in association with mitochondria may play a relevant role in the pathology of the ALS.

In line with this, alteration of the GSH/GSSG ratio may be a crucial trigger of the aggregation of mutant SOD1 and oxidized wild-type SOD1 (Ferri et al., 2006). In the light of the proposed toxicity of SOD1 oligomers and aggregates in ALS, possible strategies to counteract aggregation such as the modulation of the GSH/GSSG ratio (Ferri et al., 2006), the overexpression of cytosolic glutaredoxin 1 (Cozzolino et al., 2008) or mitochondrial glutaredoxin 2 (Ferri et al., 2010) and treatment with cisplatin (Banci et al., 2012), that binds Cys111, i.e. the crucial residue in SOD1 aggregation, have been tested. Although to different extent, all of these treatments were able to prevent or revert SOD1 aggregation in neuronal cells, ameliorating mutant G93A-SOD1 protein solubility, preserving mitochondrial function and preventing apoptosis, thus suggesting that modulation of the redox state of cysteine residues in specific compartments could be a significant therapeutic strategy for ALS. Interestingly, that glutathione deficiency leads to mitochondrial damage in the brain had been already reported in a seminal article by Alton Meister more than 25 years ago (Mårtensson et al., 1990) and it is known that GSH decreases with age (Ferguson and Bridge, 2016).

Recent experimental evidence highlighted similarities between the mechanisms of aggregation of SOD1 and TDP43. TDP43 has six cysteine residues, four of which (Cys173, Cys175, Cys198 and Cys244) are located in the two RNA recognition motifs (RRM1 and RRM2), while two others (Cys39 and Cys50) are in the N-terminal domain. No mutations in these residues have been reported so far2. Upon oxidative challenge, full length TDP43 (independently from the presence of ALS-linked mutations) is delocalized from the nucleus to the cytosol and forms both oligomers and large aggregates (Cohen et al., 2012; Bozzo et al., 2016). Studies on the aggregation process have shown that oxidation of cysteines located in the two RRMs decreases protein solubility, leading to the formation of intra and inter-molecular disulfide linkage (Cohen et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2013) and that cysteine residues in RRM1 direct the conformation of TDP43 (Shodai et al., 2013).

Formation of large aggregates is driven by oxidative stress and by partial unfolding of the hydrophobic core of the protein, whereas formation of oligomers depends on oxidative stress and clearly relies on accessible cysteine residues (Cohen et al., 2012; Shodai et al., 2013; Bozzo et al., 2016). The role of disulfide bridging as a main determinant of oligomers formation is further supported by the fact that oligomers are readily dissolved by reducing agents and by increasing available GSH (Bozzo et al., 2016), while depletion of the GSH pool induces insolubilization and fragmentation of wild type TDP43 in a motor neuron cell model (Iguchi et al., 2012).

Intriguingly, the two isoforms 35 kDa and 25 kDa deriving from the proteolytic cleavage of full length TDP43, that are found in the insoluble fraction in patients (Neumann et al., 2006) and may represent the truly toxic TDP43 species in mice (Walker et al., 2015), are totally included in cysteine-dependent oligomers (Bozzo et al., 2016).

Overall, since aggregates formed by SOD1 and TDP43 are basically present in all patients (including sALS), these data confer to a correct redox state of cysteine residues a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of ALS.

Protein Disulfide Isomerases in ALS

PDIs are members of the thioredoxin superfamily and catalyze the formation, breakage and rearrangement of disulfide bridges of proteins via oxidation, reduction and isomerization reactions (Ellgaard and Ruddock, 2005; Rutkevich et al., 2010). While the disulfide interchange enzymatic activity involved in protein folding is their most relevant function in cells (Liu et al., 2005; Parakh and Atkin, 2015), PDIs can also act as molecular chaperones preventing aggregation of proteins whether they contain disulfide bonds or not (Cai et al., 1994) and this is possibly why genes coding for PDIs are among the main targets induced by the Unfolded Protein Response transcriptional program (Matus et al., 2013). A growing body of evidence suggests a role of PDI in the pathogenesis of ALS.

PDIA1 and PDIA3 (also known as ERp57) are up-regulated in spinal cords of SOD1G93A mice, from pre-symptomatic to end stages of disease, and in tissues (spinal cord and peripheral blood mononuclear cells) from sALS patient (Atkin et al., 2006, 2008; Nardo et al., 2011). Moreover, PDIs are recruited to misfolded protein inclusions in sALS patients (Atkin et al., 2008) and interact with TDP43 and FUS inclusions in the tissues of ALS patients (Honjo et al., 2011; Farg et al., 2012). PDIs also co-localize with cytoplasmic aggregates in SOD1G93A mice and in neuronal cells in culture (Atkin et al., 2006) and with mutant vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP)-associated protein (VAP) B (VAPB) in vitro (Tsuda et al., 2008).

That increased expression of PDIs in ALS represents an attempt to protection from toxic aggregates is further suggested by studies in vitro demonstrating that overexpression of PDI reduces mutant SOD1 inclusions, whereas silencing PDI expression increases their number, and that treatment of neuronal cells with (+/−)trans-1,2-bis(mercaptoacetamido)cyclohexane, an agent that mimics PDI activity, reduces mutant SOD1 inclusions in a dose-dependent manner (Walker et al., 2010; Jeon et al., 2014).

PDIs are usually localized in the ER; however, redistribution in vesicles seems to be related to the course of the disease (Walker, 2010). PDIs redistribution is associated with a significantly increased enzymatic activity and a reduction of the inactive S-nitrosylated PDIs form (Bernardoni et al., 2013; see below). Cellular redistribution of PDIs occurs via a process involving reticulons, a family of proteins devoted to the maintenance of the ER curvature. Overexpression of reticulon-1C (Rtn1-C) or reticulon-4A (NogoA) induces a new localization of PDIs in an ALS neuronal cell model and knockdown of NogoA accelerates motor neuron degeneration in SOD1G93A transgenic mice (Yang et al., 2009; Bernardoni et al., 2013). This suggests the importance of a non-ER location of PDIs as a possible protective factor in ALS.

However, PDIs accumulation at the ER-mitochondria junction triggers apoptosis via mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization pore (Hoffstrom et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2015) and detrimental activities of PDIs in this location were identified in rat models of Huntington’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease (Sun et al., 2006; Hoffstrom et al., 2010). Similar observations in ALS models have not yet been reported; however, this aspect of PDIs’ biology would certainly deserve attention since the mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs) seem to be a critical cellular compartment in ALS. In two recent elegant articles, Miller and his group have reported that localization of both TDP43 and FUS in MAMs activates GSK-3β to disrupt the VAPB–PTPIP51 interaction and in turn ER–mitochondria associations (Stoica et al., 2014, 2016).

A further evidence of a crucial role of cysteine metabolism in ALS comes from the recent discovery of PDI mutations in patients. Intronic variants of the gene encoding PDIA1 were reported to be a genetic risk factor for sALS and fALS (Kwok et al., 2013; Yang and Guo, 2016) and nine PDIA1 missense variants and seven PDIA3 missense variants were documented in 16 ALS patients (Gonzalez-Perez et al., 2015). Expression of ALS-linked mutant forms of PDIA1 and PDIA3 in a zebrafish model impairs synaptic proteins expression and determines motor neuron morphology alterations (Gonzalez-Perez et al., 2015). Moreover, in vitro dendritic outgrowth is decreased when ALS-linked PDI mutants are expressed (Gonzalez-Perez et al., 2015). Interestingly, mice knockout for PDIA3 in the nervous system show neuro-muscular junction deficit, impaired motor performance and reduced expression of synaptic vesicle transporter protein (Woehlbier et al., 2016).

Altogether these results strongly suggest that PDIs mutations explicate their pathological effects through a loss of function mechanism, which is consistent with the report of inhibition of PDI enzymatic activity by aberrant S-nitrosylation in patients and murine experimental models (see next paragraph).

Redox-Dependent Post-Translational Modifications of Cysteines

Cysteine-dependent modifications of proteins are the most abundant post-translational modification taking place in an oxidative and/or nitrosative stress context and are considered an important mechanism of control of signal transduction.

Among these modifications, S-nitrosylation, a covalent addition of a NO group to a cysteine thiol, is generally a reversible modification (Hess et al., 2005) that may become irreversible in pathological conditions such as neurodegeneration (Nakamura et al., 2013). S-nitrosylation of PDIs has been found in several neurodegenerative disorders including ALS (Chen et al., 2013; Nakamura et al., 2013). When PDIs undergo S-nitrosylation in the active site, their enzymatic activity is inhibited and their protective functions are reduced (Benhar et al., 2006). In post-mortem spinal cord from sALS and fALS patients S-nitrosylated PDIs levels are five-fold more abundant compared to healthy controls and similarly high levels are detected in transgenic SOD1G93A mice (Walker et al., 2010). Moreover, S-nitrosylation of PDIs increases insoluble aggregates of mutant G93A-SOD1 in spinal cord of transgenic mice (Chen et al., 2013; Jeon et al., 2014). Decreased S-nitrosylation has been associated to ALS as well. A subset of fALS patients with SOD1 mutations show an increased denitrosylase activity of S-nitrosoglutathione reductase (GSNOR) and this increase has been observed also in neuronal cells expressing the same mutant SOD1 (Schonhoff et al., 2006). Moreover, GSNOR up-regulation confers resistance to NO-releasing drugs in cells expressing mutant G93A-SOD1 (Rizza et al., 2015). Because of the known impact of S-nitrosylation on mitochondrial function (Di Giacomo et al., 2012), we can speculate that modulation of S-nitrosylation and the differential accessibility of cysteines may contribute to ALS pathogenesis.

S-glutathionylation is another reversible post-translational modification induced by ROS/NOS which results in the formation of a disulfide bond between GSH and a cysteine residue of proteins (Xiong et al., 2011). This modification is involved in the regulation, through a redox signal transduction mechanism, of different enzymes implicated in cellular homeostasis e.g., in signaling pathways, antioxidant response, energy metabolism and protein folding (Mieyal et al., 2008; Grek et al., 2013). A detrimental role for S-glutathionylation in ALS has been reported. For instance, S-glutathionylation on Cys111 induces dissociation of wild type- and fALS mutant G93A-SOD1 dimers (Redler et al., 2011), triggering monomer formation and subsequent aggregation (Wilcox et al., 2009; McAlary et al., 2013).

Finally, a growing body of evidence suggests that also cysteine palmitoylation could be implicated in ALS. Palmitoylation is the only lipid modification that can be reversibly regulated; its main role seems to be to constitute rafts that allow the dynamic targeting of specific proteins to membranes (Levental et al., 2010). It was observed that Cys6 can be palmitoylated in wild type SOD1 and that two fALS SOD1 mutants are more exposed to this change in motor neuronal cells and in the spinal cord of SOD1G93A transgenic mice (Antinone et al., 2013). Moreover, palmitoylation takes place mainly on reduced disulfides, suggesting that immature SOD1 is the species primarily subject to this modification, and therefore increased when the cysteine residues are more exposed as observed for several mutant SOD1s (Antinone et al., 2013).

Conclusions

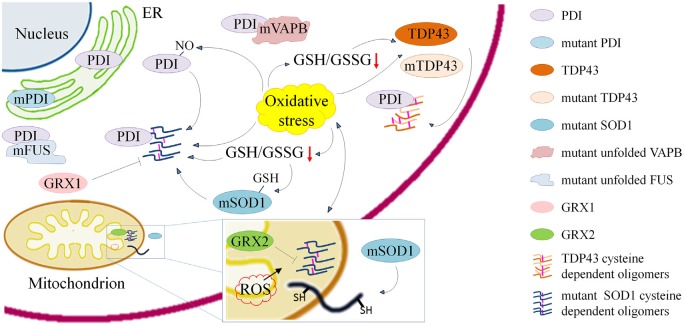

As outlined above, dysregulation of the redox state of cysteines seems to be involved in a number of mechanisms that are important for the maintenance of correct protein folding and activity in ALS (Figure 1 and Table 1). Other aspects of cysteine metabolism may be relevant in the pathogenesis of ALS, such as the direct oxidation of cysteines in proteins that are crucial for motor neuron metabolism and survival. One example is cysteines oxidation in AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) that is known to increase its activity (Zmijewski et al., 2010; Cardaci et al., 2012; Jeon and Hay, 2015). Intriguingly, an increased AMPK activity was reported in motor neuron cells expressing mutant SOD1 or TDP43 (Lim et al., 2012; Perera et al., 2014; Sui et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2015), in embryonic neural stem cells derived from SOD1G93A mice (Perera et al., 2014) and in motor neurons of sALS and fALS patients (Liu et al., 2015). Moreover, pharmacological inhibition of AMPK activity rescued TDP43 mislocalization in neuronal cells and delayed disease progression in TDP43 transgenic mice (Liu et al., 2015) whereas genetic reduction of AMPK ortholog improved locomotor behavior and fecundity of C. elegans expressing G85R-SOD1 or M337V-TDP43 (Lim et al., 2012).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of processes involving cysteine residues and that are relevant in the pathogenesis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) either through the induction of misfolding, aggregation and delocalization of proteins or through their inactivation. Cysteine dependent protein aggregation in ALS is promoted by oxidative stress and reduced γ-L-Glutamyl-L-cysteinylglycine (GSH)/glutathione disulfide (GSSG) ratio. Wild type and mutant transactive response DNA-binding protein (TDP43) form cytoplasmic oligomers based on the accessibility of cysteine residues. Mutant superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) forms cytoplasmic and mitochondrial oligomers that can be reduced by overexpression of anti-oxidant proteins cytosolic Glutaredoxin 1 and mitochondrial Glutaredoxin 2. Cys-glutathionylation of mSOD1 and Cys-nitrosylation of protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) enhance aggregation of mSOD1. ALS associated PDI mutations suggest a crucial role of the cysteine-mediated folding in the disease. PDIs colocalize with mSOD1 and TDP43 oligomers and with mutant fused in sarcoma (FUS) and vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP)-associated protein (VAP) B (VAPB).

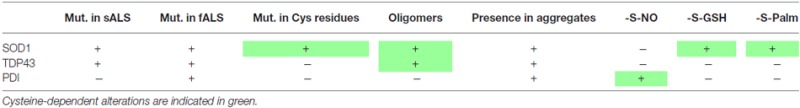

Table 1.

Involvement of cysteine residues in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

|

On the whole, studies exploring the possibility to modulate the redox state of cysteines are warranted with the aim of finding new therapeutic approaches for this disease. While genetic modulation of proteins involved in cysteine homeostasis is still an unfeasible approach in man, pharmacological interventions (e.g., to increase GSH/GSSG ratio or PDI activity) may hold great promise in the treatment of ALS.

Author Contributions

CV and MTC formulated the entire concept of manuscript. CV executed complete drawing of figure. Both authors reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca (MIUR)-PRIN (2015LFPNMN_002 to MTC). We apologize to many authors whose work could not be included due to space limitations.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ALS

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- fALS

familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- FUS/TLS

fused in sarcoma/translocated in liposarcoma protein

- GSH

reduced glutathione

- GSNOR

S-nitrosoglutathione reductase

- GSSG

oxidized glutathione

- IMS

internal mitochondrial space

- MAM

mitochondria-associated ER membranes

- PDI

protein disulfide isomerase

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RRM

RNA recognition motif

- sALS

sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- SOD1

Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase

- TDP43

transactive response DNA-binding protein

- VAPB

vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP)-associated protein (VAP) B.

Footnotes

References

- Antinone S. E., Ghadge G. D., Lam T. T., Wang L., Roos R. P., Green W. N. (2013). Palmitoylation of superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) is increased for familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked SOD1 mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 21606–21617. 10.1074/jbc.M113.487231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin J. D., Farg M. A., Turner B. J., Tomas D., Lysaght J. A., Nunan J., et al. (2006). Induction of the unfolded protein response in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and association of protein-disulfide isomerase with superoxide dismutase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 30152–30165. 10.1074/jbc.M603393200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin J. D., Farg M. A., Walker A. K., McLean C., Tomas D., Horne M. K. (2008). Endoplasmic reticulum stress and induction of the unfolded protein response in human sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol. Dis. 30, 400–407. 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banci L., Bertini I., Blaževitš O., Calderone V., Cantini F., Mao J., et al. (2012). Interaction of cisplatin with human superoxide dismutase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 7009–7014. 10.1021/ja211591n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banci L., Bertini I., Boca M., Girotto S., Martinelli M., Valentine J. S., et al. (2008). SOD1 and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: mutations and oligomerization. PLoS One 3:e1677. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber S. C., Shaw P. J. (2010). Oxidative stress in ALS: key role in motor neuron injury and therapeutic target. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 48, 629–641. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benhar M., Forrester M. T., Stamler J. S. (2006). Nitrosative stress in the ER: a new role for S-nitrosylation in neurodegenerative diseases. ACS Chem. Biol. 1, 355–358. 10.1021/cb600244c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardoni P., Fazi B., Costanzi A., Nardacci R., Montagna C., Filomeni G., et al. (2013). Reticulon1-C modulates protein disulphide isomerase function. Cell Death Dis. 4:e581. 10.1038/cddis.2013.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozzo F., Salvatori I., Iacovelli F., Mirra A., Rossi S., Cozzolino M., et al. (2016). Structural insights into the multi-determinant aggregation of TDP-43 in motor neuron-like cells. Neurobiol. Dis. 94, 63–72. 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H., Wang C. C., Tsou C. L. (1994). Chaperone-like activity of protein disulfide isomerase in the refolding of a protein with no disulfide bonds. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 24550–24552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardaci S., Filomeni G., Ciriolo M. R. (2012). Redox implications of AMPK-mediated signal transduction beyond energetic clues. J. Cell Sci. 125, 2115–2125. 10.1242/jcs.095216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers J. E., Marciniak S. J. (2014). Cellular mechanisms of endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling in health and disease. 2. Protein misfolding and ER stress. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 307, C657–C670. 10.1152/ajpcell.00183.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. K., Chiang M. H., Toh E. K., Chang C. F., Huang T. H. (2013). Molecular mechanism of oxidation-induced TDP-43 RRM1 aggregation and loss of function. FEBS Lett. 587, 575–582. 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.01.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatzi A., Manganas P., Tokatlidis K. (2016). Oxidative folding in the mitochondrial intermembrane space: a regulated process important for cell physiology and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1863, 1298–1306. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Zhang X., Li C., Guan T., Shang H., Cui L., et al. (2013). S-nitrosylated protein disulfide isomerase contributes to mutant SOD1 aggregates in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurochem. 124, 45–58. 10.1111/jnc.12046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen T. J., Hwang A. W., Unger T., Trojanowski J. Q., Lee V. M. (2012). Redox signalling directly regulates TDP-43 via cysteine oxidation and disulphide cross-linking. EMBO J. 31, 1241–1252. 10.1038/emboj.2011.471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzolino M., Ferri A., Carrì M. T. (2008). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: from current developments in the laboratory to clinical implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10, 405–444. 10.1089/ars.2007.1760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzolino M., Pesaresi M. G., Amori I., Crosio C., Ferri A., Nencini M., et al. (2009). Oligomerization of mutant SOD1 in mitochondria of motoneuronal cells drives mitochondrial damage and cell toxicity. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 1547–1558. 10.1089/ARS.2009.2545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellgaard L., Ruddock L. W. (2005). The human protein disulphide isomerase family: substrate interactions and functional properties. EMBO Rep. 6, 28–32. 10.1038/sj.embor.7400311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farg M. A., Soo K. Y., Walker A. K., Pham H., Orian J., Horne M. K., et al. (2012). Mutant FUS induces endoplasmic reticulum stress in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and interacts with protein disulfide-isomerase. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 2855–2868. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feige M. J., Hendershot L. M. (2011). Disulfide bonds in ER protein folding and homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23, 167–175. 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson G., Bridge W. (2016). Glutamate cysteine ligase and the age-related decline in cellular glutathione: the therapeutic potential of γ-glutamylcysteine. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 593, 12–23. 10.1016/j.abb.2016.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri A., Cozzolino M., Crosio C., Nencini M., Casciati A., Gralla E. B., et al. (2006). Familial ALS-superoxide dismutases associate with mitochondria and shift their redox potentials. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 103, 13860–13865. 10.1073/pnas.0605814103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri A., Fiorenzo P., Nencini M., Cozzolino M., Pesaresi M. G., Valle C., et al. (2010). Glutaredoxin 2 prevents aggregation of mutant SOD1 in mitochondria and abolishes its toxicity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 4529–4542. 10.1093/hmg/ddq383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman H. J. (2016). Redox signaling: an evolution from free radicals to aging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 97, 398–407. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giacomo G., Rizza S., Montagna C., Filomeni G. (2012). Established principles and emerging concepts on the interplay between mitochondrial physiology and S-(De)nitrosylation: implications in cancer and neurodegeneration. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2012:361872. 10.1155/2012/361872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Perez P., Woehlbier U., Chian R. J., Sapp P., Rouleau G. A., Leblond C. S., et al. (2015). Identification of rare protein disulfide isomerase gene variants in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Gene 566, 158–165. 10.1016/j.gene.2015.04.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grek C. L., Zhang J., Manevich Y., Townsend D. M., Tew K. D. (2013). Causes and consequences of cysteine S-glutathionylation. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 26497–26504. 10.1074/jbc.r113.461368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess D. T., Matsumoto A., Kim S. O., Marshall H. E., Stamler J. S. (2005). Protein S-nitrosylation: purview and parameters. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 150–166. 10.1038/nrm1569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffstrom B. G., Kaplan A., Letso R., Schmid R. S., Turmel G. J., Lo D. C., et al. (2010). Inhibitors of protein disulfide isomerase suppress apoptosis induced by misfolded proteins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 900–906. 10.1038/nchembio.467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honjo Y., Kaneko S., Ito H., Horibe T., Nagashima M., Nakamura M., et al. (2011). Protein disulfide isomerase-immunopositive inclusions in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 12, 444–450. 10.3109/17482968.2011.594055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi Y., Katsuno M., Takagi S., Ishigaki S., Niwa J., Hasegawa M., et al. (2012). Oxidative stress induced by glutathione depletion reproduces pathological modifications of TDP-43 linked to TDP-43 proteinopathies. Neurobiol. Dis. 45, 862–870. 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon S. M., Hay N. (2015). The double-edged sword of AMPK signaling in cancer and its therapeutic implications. Arch. Pharm. Res. 38, 346–357. 10.1007/s12272-015-0549-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon G. S., Nakamura T., Lee J. S., Choi W. J., Ahn S. W., Lee K. W., et al. (2014). Potential effect of S-nitrosylated protein disulfide isomerase on mutant SOD1 aggregation and neuronal cell death in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol. Neurobiol. 49, 796–807. 10.1007/s12035-013-8562-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. P. (2008). Radical-free biology of oxidative stress. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 295, C849–C868. 10.1152/ajpcell.00283.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch C. M., Prudencio M., Winkler D. D., Hart P. J., Borchelt D. R. (2009). Role of mutant SOD1 disulfide oxidation and aggregation in the pathogenesis of familial ALS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 106, 7774–7779. 10.1073/pnas.0902505106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamata H., Manfredi G. (2010). Import, maturation, and function of SOD1 and its copper chaperone CCS in the mitochondrial intermembrane space. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 13, 1375–1384. 10.1089/ars.2010.3212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok C. T., Morris A. G., Frampton J., Smith B., Shaw C. E., de Belleroche J. (2013). Association studies indicate that protein disulfide isomerase is a risk factor in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 58, 81–86. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E. B., Lee V. M., Trojanowski J. Q. (2011). Gains or losses: molecular mechanisms of TDP43-mediated neurodegeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 38–50. 10.1038/nrn3121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levental I., Lingwood D., Grzybek M., Coskun U., Simons K. (2010). Palmitoylation regulates raft affinity for the majority of integral raft proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 107, 22050–22054. 10.1073/pnas.1016184107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., O W., Li W., Jiang Z. G., Ghanbari H. A. (2013). Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 24438–24475. 10.3390/ijms141224438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim M. A., Selak M. A., Xiang Z., Krainc D., Neve R. L., Kraemer B. C., et al. (2012). Reduced activity of AMP-activated protein kinase protects against genetic models of motor neuron disease. J. Neurosci. 32, 1123–1141. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6554-10.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. J., Ju T. C., Chen H. M., Jang Y. S., Lee L. M., Lai H. L., et al. (2015). Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase α1 mediates mislocalization of TDP-43 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, 787–801. 10.1093/hmg/ddu497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Zhao T. J., Yan Y. B., Zhou H. M. (2005). Increase of soluble expression in Escherichia coli cytoplasm by a protein disulfide isomerase gene fusion system. Protein Expr. Purif. 44, 155–161. 10.1016/j.pep.2005.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mårtensson J., Jain A., Meister A. (1990). Glutathione is required for intestinal function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 87, 1715–1719. 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matus S., Valenzuela V., Medinas D. B., Hetz C. (2013). ER dysfunction and protein folding stress in ALS. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2013:674751. 10.1155/2013/674751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlary L., Yerbury J. J., Aquilina J. A. (2013). Glutathionylation potentiates benign superoxide dismutase 1 variants to the toxic forms associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Sci. Rep. 3:3275. 10.1038/srep03275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister A. (1988). Glutathione metabolism and its selective modification. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 17205–17208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mieyal J. J., Gallogly M. M., Qanungo S., Sabens E. A., Shelton M. D. (2008). Molecular mechanisms and clinical implications of reversible protein S-glutathionylation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10, 1941–1988. 10.1089/ars.2008.2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mordas A., Tokatlidis K. (2015). The MIA pathway: a key regulator of mitochondrial oxidative protein folding and biogenesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 2191–2199. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T., Tu S., Akhtar M. W., Sunico C. R., Okamoto S., Lipton S. A. (2013). Aberrant protein S-nitrosylation in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuron 78, 596–614. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardo G., Pozzi S., Pignataro M., Lauranzano E., Spano G., Garbelli S., et al. (2011). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis multiprotein biomarkers in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. PLoS One 6:e25545. 10.1371/journal.pone.0025545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann M., Sampathu D. M., Kwong L. K., Truax A. C., Micsenyi M. C., Chou T. T., et al. (2006). Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 314, 130–133. 10.1126/science.1134108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa J., Yamada S., Ishigaki S., Sone J., Takahashi M., Katsuno M., et al. (2007). Disulfide bond mediates aggregation, toxicity, and ubiquitylation of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked mutant SOD1. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 28087–28095. 10.1074/jbc.m704465200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka O. B., Bulleid N. J. (2013). Forming disulfides in the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833, 2425–2429. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parakh S., Atkin J. D. (2015). Novel roles for protein disulphide isomerase in disease states: a double edged sword? Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 3:30. 10.3389/fcell.2015.00030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera N. D., Sheean R. K., Scott J. W., Kemp B. E., Horne M. K., Turner B. J. (2014). Mutant TDP-43 deregulates AMPK activation by PP2A in ALS models. PLoS One 9:e95549. 10.1371/journal.pone.0095549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters O. M., Ghasemi M., Brown R. H., Jr. (2015). Emerging mechanisms of molecular pathology in ALS. J. Clin. Invest. 125:2548. 10.1172/JCI82693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redler R. L., Wilcox K. C., Proctor E. A., Fee L., Caplow M., Dokholyan N. V. (2011). Glutathionylation at Cys-111 induces dissociation of wild type and FALS mutant SOD1 dimers. Biochemistry 50, 7057–7066. 10.1021/bi200614y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renton A. E., Chiò A., Traynor B. J. (2014). State of play in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 17–23. 10.1038/nn.3584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizza S., Cirotti C., Montagna C., Cardaci S., Consales C., Cozzolino M., et al. (2015). S-nitrosoglutathione reductase plays opposite roles in SH-SY5Y models of Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2015:536238. 10.1155/2015/536238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robberecht W., Philips T. (2013). The changing scene of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 248–264. 10.1038/nrn3430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkevich L. A., Cohen-Doyle M. F., Brockmeier U., Williams D. B. (2010). Functional relationship between protein disulfide isomerase family members during the oxidative folding of human secretory proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 3093–3105. 10.1091/mbc.E10-04-0356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki S., Maruyama S. (1994). Synapse loss in anterior horn neurons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 88, 222–227. 10.1007/s004010050153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonhoff C. M., Matsuoka M., Tummala H., Johnson M. A., Estevéz A. G., Wu R., et al. (2006). S-nitrosothiol depletion in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 103, 2404–2409. 10.1073/pnas.0507243103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shodai A., Morimura T., Ido A., Uchida T., Ayaki T., Takahashi R., et al. (2013). Aberrant assembly of RNA recognition motif 1 links to pathogenic conversion of TAR DNA-binding protein of 43 kDa (TDP-43). J. Biol. Chem. 288, 14886–14905. 10.1074/jbc.M113.451849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoica R., De Vos K. J., Paillusson S., Mueller S., Sancho R. M., Lau K. F., et al. (2014). ER–mitochondria associations are regulated by the VAPB-PTPIP51 interaction and are disrupted by ALS/FTD-associated TDP-43. Nat. Commun. 5:3996. 10.1038/ncomms4996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoica R., Paillusson S., Gomez-Suaga P., Mitchell J. C., Lau D. H., Gray E. H., et al. (2016). ALS/FTD-associated FUS activates GSK-3β to disrupt the VAPB-PTPIP51 interaction and ER-mitochondria associations. EMBO Rep. 17, 1326–1342. 10.15252/embr.201541726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui Y., Zhao Z., Liu R., Cai B., Fan D. (2014). Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase activation enhances embryonic neural stem cell apoptosis in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neural Regen. Res. 9, 1770–1778. 10.4103/1673-5374.143421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., He G., Qing H., Zhou W., Dobie F., Cai F., et al. (2006). Hypoxia facilitates Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis by up-regulating BACE1 gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 103, 18727–18732. 10.1073/pnas.0606298103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda H., Han S. M., Yang Y., Tong C., Lin Y. Q., Mohan K., et al. (2008). The amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 8 protein VAPB is cleaved, secreted, and acts as a ligand for Eph receptors. Cell 133, 963–977. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker A. K. (2010). Protein disulfide isomerase and the endoplasmic reticulum in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurosci. 30, 3865–3867. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0408-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker A. K., Farg M. A., Bye C. R., McLean C. A., Horne M. K., Atkin J. D. (2010). Protein disulphide isomerase protects against protein aggregation and is S-nitrosylated in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 133, 105–116. 10.1093/brain/awp267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker A. K., Tripathy K., Restrepo C. R., Ge G., Xu Y., Kwong L. K., et al. (2015). An insoluble frontotemporal lobar degeneration-associated TDP-43 C-terminal fragment causes neurodegeneration and hippocampus pathology in transgenic mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, 7241–7254. 10.1093/hmg/ddv424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter P., Ron D. (2011). The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science 334, 1081–1086. 10.1126/science.1209038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann F. R., Manfredi G., Mawrin C., Beal M. F., Schon E. A. (2002). Mitochondrial DNA and respiratory chain function in spinal cords of ALS patients. J. Neurochem. 80, 616–625. 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00731.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox K. C., Zhou L., Jordon J. K., Huang Y., Yu Y., Redler R. L., et al. (2009). Modifications of superoxide dismutase (SOD1) in human erythrocytes: a possible role in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 13940–13947. 10.1074/jbc.M809687200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woehlbier U., Colombo A., Saaranen M. J., Pérez V., Ojeda J., Bustos F. J., et al. (2016). ALS-linked protein disulfide isomerase variants cause motor dysfunction. EMBO J. 35, 845–865. 10.15252/embj.201592224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y., Uys J. D., Tew K. D., Townsend D. M. (2011). S-glutathionylation: from molecular mechanisms to health outcomes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 15, 233–270. 10.1089/ars.2010.3540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Guo Z. B. (2016). Polymorphisms in protein disulfide isomerase are associated with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in the Chinese Han population. Int. J. Neurosci. 126, 607–611. 10.3109/00207454.2015.1050098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. S., Harel N. Y., Strittmatter S. M. (2009). Reticulon-4A (Nogo-A) redistributes protein disulfide isomerase to protect mice from SOD1-dependent amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurosci. 29, 13850–13859. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2312-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G., Lu H., Li C. (2015). Proapoptotic activities of protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) and PDIA3 protein, a role of the Bcl-2 protein Bak. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 8949–8963. 10.1074/jbc.M114.619353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zmijewski J. W., Banerjee S., Bae H., Friggeri A., Lazarowski E. R., Abraham E. (2010). Exposure to hydrogen peroxide induces oxidation and activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 33154–33164. 10.1074/jbc.M110.143685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]