Abstract

The use of acellular dermal matrices (ADM) for dural repair is very scantily described in the literature. We report two cases of dural repair using porcine ADM and a literature review. ADM and especially StratticeTM pliable may be a useful alternative to other dural substitutes. Further evaluation would be favorable.

Keywords: Acellular dermal matrix, porcine acellular dermal matrix, strattice, dural repair, dural substitute

Introduction

The dura mater is the outermost layer of the meningeal tissue. Defects often arise from trauma or surgical procedures. The commonly accepted approach is surgical repair of the dural defect to restore tissue homeostasis and barrier functions [1]. The repair must be fluid-tight to prevent, among others, postoperative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) fistula, infections, and pseudomeningocele [2].

Since the 1890s, several materials have been used as dural grafts. At this point, the most commonly used substitutes are autologous grafts, e.g. fascia lata and galea-pericranium, or synthetic meshes [3,4]. The synthetic meshes can be either absorbable or non-absorbable.

Acellular dermal matrices (ADM) have been used in soft tissue reconstructions since 1995, initially applied for treatment of burns [5]. The ADM acts as a scaffold for cellular infiltration. In time, it will incorporate into the surrounding tissue [6]. In 1999, Chaplin and colleagues presented an experimental study evaluating the use of a porcine ADM (XenoDermTM; Acelity, San Antonio, TX) in a porcine model [7]. In 2000, Warren and colleagues were the first to report their experiences on human ADM (AlloDerm®; Acelity, San Antonio, TX) as a dural substitute in humans [8]. Their experiences were promising and in accordance with a minor long-term study published later the same year [9].

We present two cases of dural defect repair using StratticeTM pliable (Acelity, San Antonio, TX), a porcine ADM. To our knowledge, this has not previously been reported from other institutions [10].

The product is purchased from Acelity. The company have no influence on the outcome of this paper.

Case Report(s)

Case 1

A 60-year-old man with the Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome, and a history of five solid tumors, developed a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in the sacral area. It was initially treated with excision and radiotherapy (66 Gy in 33 fractions). However, two years later, the malignant tumor recurred. The tumor was, again, treated with excision. Surgery resulted in a small lesion in dura. The lesion was primarily repaired by tegmentatio and sealed with TisseelTM (Baxter Int. Inc., DeerField, IL). Transposition of adjacent muscles ensured soft tissue coverage. Eighteen days postoperatively, magnetic resonance images (MRI) revealed a CSF accumulation superficial to the dura. A second repair with a fascia lata autograft and a synthetic mesh was done. A few days after the second surgery, a new CSF accumulation formed. With assistance from the Department of plastic surgery, a dural repair using StratticeTM pliable was made.

Surgical technique

Primarily, the synthetic mesh and necrotic tissue were excised. A suitable piece of StratticeTM pliable was placed over the defect and with single-sutures, through drill holes, fixed to the sacral bone and by running sutures to the adjacent muscles. The suture line was covered with TachoSil® (Baxter Int. Inc., DeerField, IL). After undermining the muscles superficial to the fascia, the soft tissue was closed layer by layer. A subfascial drain was inserted and removed after seven days. Furthermore a vacuum system was placed on the skin covering the wound. This was removed after five days.

Three months later, a Computed Tomography of Thorax, Abdomen, and Pelvis (CT-TAP) revealed new entrant bone and lung metastasis, and the patient was offered palliative radiotherapy. The patient did not experience further CSF-leakage and did unfortunately died two months later.

Case 2

A 29-year-old woman diagnosed with Arnold Chiari malformations had an occipitocervical decompression surgery, due to progressive headache, in 2013. Two years later, a second decompression surgery was done due to progressive ataxia and paraesthesia in her right arm. During the surgery, a titanium plate was attached to the remains of C1, and a synthetic dural substitute was inserted. Postoperatively two MRI scans within a month revealed accumulation of CSF superficial to the dural repair site. A dural repair with a synthetic mesh was repeated twice. When the patient for the third time leaked CSF from the wound, the leakage was sealed with porcine ADM (StratticeTM pliable).

Surgical technique

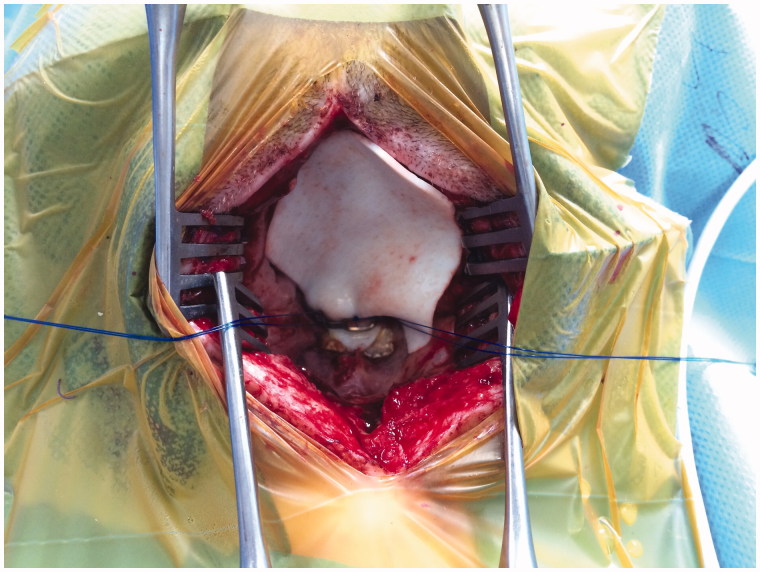

A suitable piece of StratticeTM pliable was placed over the leak site and sutured, see Figure 1. Before closing, the ADM was covered with TachoSil® and TissellTM. After insertion, no CSF leakage was observed. However, the inserted ADM pulsated. The soft tissue was closed in layers. No drains were inserted.

Figure 1.

Clinical photo.

Eight months postoperatively, the patient had not experienced further setbacks. The healing process is ongoing.

Discussion

Despite more than a century of investigation and experimentation, research for the ideal substitute for dural repair continues. In spite of promising results using AlloDerm® as a dural substitute, experiments with other ADM products have, to our knowledge, not been reported.

At our institution, we have great experience with porcine ADM StratticeTM for a wide range of reconstructive procedures, i.e. breast reconstructions, thoracic wall and abdominal wall reconstructions. In addition, the ADM has also been used for static reconstructions after facial nerve paralysis. Moreover, the porcine ADM (StratticeTM) was chosen as the other available bovine ADM (Surgimend® PRS; TEI Biosciences Inc., Boston, MA) is fenestrated whereas StratticeTM is not.

StratticeTM pliable is the porcine counterpart to AlloDerm® and widely used in breast reconstructions. Here, StratticeTM pliable is at least equal to AlloDerm® regarding to outcome [11]. Hence, an obvious choice to use.

The ideal dura substitute must fulfill several requirements. It must be strong, be flexible, maintain structural integrity after suturing, be fluid-tight, be fully incorporative, not induce host response, not form adhesion to the underlying tissue, and act as a barrier to acute and chronic infections [3,4].

ADM is derived from mammalian dermis and further processed in different ways. After processing, the matrix contains only collagen fibers, elastin, hyaluronic acid, fibronectin, proteoglycans, and releasable growth factors. All cellular components are removed in the process [12]. Among others, the properties of the ADM depend on the origin [13]. StratticeTM pliable is flexible but has been shown to be both stronger and stiffer compared to AlloDerm® [6,14]. When suturing StratticeTM pliable, deformity may hardly be considerable [6]. Hence, a repair using StratticeTM pliable will most likely be fluid-tight, if placed correctly. Previously it has been questioned whether incorporation of non-human grafts into the human body would induce a stronger immunologic/inflammatory response compared to allografts [8]. This seems not to be the case [11]. In breast reconstructions, StratticeTM pliable seems fully incorporated within six months. Only during the first two weeks, moderate to significant inflammatory response consistent to normal wound healing is observed [3]. Hence, only the first two weeks seems critical in regard to undesirable adhesion to the underlying tissue. Whether this also applies in dural repairs must rely on further evaluations. However, Warren and colleagues did not experience any cases of adhesion formation or rejection using AlloDerm® [8]. Due to great similarity between AlleDerm® and StratticeTM, it suggests that there might be accordance between theory and practice.

Another favorable feature of StratticeTM is the supposed protective effect to microbial penetration of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus pyogene, two very common skin bacteria [15]. Therefore, one may think that in case of infection, it does not necessarily lead to removal of the allograft, as it does not seem to get penetrated by bacteria. This could be due to the neoangiogenesis that ensure the presence of immune cells inside the ADM. This is in concordance to the experiences of Warren and colleagues. They observed a few cases of superficial infection, apparently sparing the ADM. They managed to refrain from removing the ADM, treating the infection with antibiotics only. The infections did not require further treatment [8].

In Case 1, vacuum was used to assist the healing. The use of vacuum therapy is shown to significantly increase blood flow and decrease the rate of infection in the treated area [16]. It can be hypothesized that combining vacuum therapy with implantation of an ADM would decrease the incorporative process in a time perspective, due to higher infiltration rate.

Besides cost, and the above-mentioned requirements, the surgeon may consider other aspects concerning choice of graft and technique. Autografts is not always available/obtainable opposite to allografts, and not to mention the absence of donor-site morbidity, e.g. pain, bleeding, and infection.

In our two cases, StratticeTM pliable was introduced after several attempts to repair a dural lesion using more traditional methods. Despite this, StratticeTM pliable instantly created a fluid-tight barrier. Some may consider using ADM as a last option. But introducing ADM at an earlier stage may however lower the total costs, by lowering the number of surgical interventions and days of admission.

Based on the published literature, StratticeTM pliable seems to meet the requirements for an ideal dural substitute. In our experience, StratticeTM pliable may be a feasible alternative to other dural substitutes. Additional investigation is needed to elucidate this further, preferable as randomized clinical trials.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Meng F, Modo M, Badylak SF. Biologic scaffold for CNS repair. Regen Med. 2014;9:367–383. doi: 10.2217/rme.14.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatino G, Pepa Della GM, Bianchi F, et al. Autologous dural substitutes: a prospective study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;116:20–23. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shridharani SM, Tufaro AP. A systematic review of acelluar dermal matrices in head and neck reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:35S–43S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31825eff7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartosz DK, Vasterling MK. Dura mater substitutes in the surgical treatment of meningiomas. J Neurosci Nurs. 1994;26:140–145. doi: 10.1097/01376517-199406000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright DJ. Use of an acellular allograft dermal matrix (AlloDerm) in the management of full-thickness burns. Burns. 1995;21:243–248. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(95)93866-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor J, McQuillan D, Sandor M, et al. Retention of structural and biochemical integrity in a biological mesh supports tissue remodeling in a primate abdominal wall model. Regen Med. 2009;4:185–195. doi: 10.2217/17460751.4.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin JM, Costantino PD, Wolpoe ME, et al. Use of an acellular dermal allograft for dural replacement: an experimental study. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:320–327. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199908000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren WL, Medary MB, Dureza CD, et al. Dural repair using acellular human dermis: experience with 200 cases: technique assessment. Neurosurg. 2000;46:1391–1396. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200006000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantino PD, Wolpoe ME, Govindaraj S, et al. Human dural replacement with acellular dermis: clinical results and a review of the literature. Head Neck. 2000;22:765–771. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200012)22:8<765::aid-hed4>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damsgaard TE, Hammer-Hansen N, Eschen GT, et al. Porcine acellular dermal matrix for reconstruction of the dura in recurrent malignant schwannoma of the scalp. Eur J Plast Surg. 2016;39:61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Glasberg SB, Light D. AlloDerm and Strattice in breast reconstruction: a comparison and techniques for optimizing outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:1223–1233. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31824ec429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocak E, Nagel TW, Hulsen JH, et al. Biologic matrices in oncologic breast reconstruction after mastectomy. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2014;11:65–75. doi: 10.1586/17434440.2014.864087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers CA, Dearth CL, Reing JE, et al. Histologic characterization of acellular dermal matrices in a porcine model of tissue expander breast reconstruction. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;0:1–10. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2014.0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melman L, Jenkins ED, Hamilton NA, et al. Early biocompatibility of crosslinked and non-crosslinked biologic meshes in a porcine model of ventral hernia repair. Hernia. 2011;15:157–164. doi: 10.1007/s10029-010-0770-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenbach EN, Qi C, Ibrahim O, et al. Resistance of acellular dermal matrix materials to microbial penetration. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:571–575. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers AK, Neal MT, Argenta LC, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure for complex cranial wounds involving the loss of dura mater. J Neurosurg. 2013;118:302–308. doi: 10.3171/2012.10.JNS112241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]