Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the efficacy and safety of CS1002, an over-the-counter cough treatment containing diphenhydramine, ammonium chloride and levomenthol in a cocoa-based demulcent.

Design

A multicentre, randomised, parallel group, controlled, single-blinded study in participants with acute upper respiratory tract infection-associated cough.

Setting

4 general practitioner (GP) surgeries and 14 pharmacies in the UK.

Participants

Participants aged ≥18 years who self-referred to a GP or pharmacist with acute cough of <7 days' duration. Participant inclusion criterion was cough severity ≥60 mm on a 0–100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS). Exclusion criteria included current smokers or history of smoking within the past 12 months (including e-cigarettes). 163 participants were randomised to the study (mean participant age 38 years, 57% females).

Interventions

Participants were randomised to CS1002 (Unicough) or simple linctus (SL), a widely used cough treatment, and treatment duration was 7 days or until resolution of cough.

Main outcome measures

The primary analysis was intention-to-treat (157 participants) and comprised cough severity assessed using a VAS after 3 days' treatment (prespecified primary end point at day 4). Cough frequency, sleep disruption, health status (Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ-acute)) and cough resolution were also assessed.

Results

At day 4 (primary end point), the adjusted mean difference (95% CI) in cough severity VAS between CS1002 and SL was −5.9 mm (−14.4 to 2.7), p=0.18. At the end of the study (day 7) the mean difference in cough severity VAS was −4.2 mm (−12.2 to 3.9), p=0.31. CS1002 was associated with a greater reduction in cough sleep disruption (mean difference −11.6 mm (−20.6 to 2.7), p=0.01) and cough frequency (mean difference −8.1 mm (−16.2 to 0.1), p=0.05) compared with SL. There was greater improvement in LCQ-acute quality of life scores with CS1002 compared with SL: mean difference (95% CI) 1.2 (0.05 to 2.36), p=0.04 after 5 days' treatment. More participants prematurely stopped treatment due to cough improvement in the CS1002 group (24.4%) compared with SL (10.7%; p=0.02). Adverse events (AEs) were comparable between CS1002 (20.5%) and SL (27.6%) and largely related to the study indication. 6 participants (7%) in the CS1002 group reduced the dose of medication due to drowsiness/tiredness, which subsequently resolved. These events were not reported by participants as AEs.

Conclusions

Although the primary end point was not achieved, CS1002 was associated with greater reductions in cough frequency, sleep disruption and improved health status compared with SL.

Trial registration number

EudraCT number 2014-004255-31.

Keywords: Controlled clinical trial, Cough, Demulcent, Diphenhydramine, Simple Linctus

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A recent Cochrane systematic review of cough medicines found no good evidence for or against the effectiveness of over-the-counter medications in acute cough.

This is one of the largest multiple dosing, multicentre, randomised, controlled trials in participants with cough to date, and the first to recruit participants seeking cough medicines at pharmacies and is therefore more likely to represent the broader population with acute cough due to upper respiratory tract infection.

Participants were unselected for the category of cough, and included a broad range of participants with self-reported dry, chesty and tickly cough.

The study was single-blinded because an active control, simple linctus, was used as the comparator but it is possible that there may have been greater differences in efficacy outcome measures if an inactive placebo had been used.

Our findings highlight the challenges of evaluating cough medicines in a rapidly improving condition and will facilitate the design of future studies of acute cough.

Introduction

Approximately one in five people in the UK suffer an acute cough over the winter1 and it is one of the most common reasons for consulting a general practitioner (GP), at a cost to the National Health Service (NHS) of ∼£2 billion per year.2–4 Although most acute coughs improve spontaneously, many patients use over-the-counter (OTC) medicines. In 2014, £98.7 million was spent in the UK on OTC cough treatments.5 OTC cough medicines include antitussives, expectorants, mucolytics, antihistamines, decongestants and numerous drug combinations.6 There is a lack of data supporting the efficacy of OTC medicines in the treatment of acute cough associated with upper respiratory tract infection (URTI). In 2012, a Cochrane systematic review concluded there was no strong evidence for or against their effectiveness.6 Methodological flaws in clinical trial design, paucity of placebo-controlled trials, use of unvalidated outcome measures and inefficacy of medicines were some of the reasons for the poor evidence base.

CS1002 is an OTC cough medicine that contains three active ingredients: diphenhydramine, levomenthol and ammonium chloride in a cocoa-based demulcent preparation. Diphenhydramine is an antihistamine that has been reported to reduce the heightened cough reflex sensitivity in participants with cough associated with an URTI.7 Menthol and eucalyptus have been used for many centuries for treating coughs and colds.8 Menthol is obtained from mint oils, mainly peppermint, or made synthetically from coal tar. It has a pungent odour that provides a cooling and soothing effect in the mouth and throat and is often used to relieve congestion.8 Menthol has also been reported to inhibit cough reflex sensitivity compared with placebo.9 Ammonium chloride is an acid-forming salt that is thought to exert an expectorant effect by loosening sputum.10 The effectiveness and mode of action of ammonium chloride remains controversial.10 The cocoa-based demulcent preparation used in CS1002 is more viscous than most available OTC cough medicines. Demulcents are thought to reduce cough and cold symptoms because of a soothing effect on the mucus membrane.11 The aim of this study was to investigate the efficacy of CS1002, an OTC cough medicine for cough associated with URTI, in a randomised controlled trial.

Methods

Study design

This multicentre, randomised, parallel group, controlled, single-blinded study was conducted in 4 GP surgeries and 14 pharmacies in the UK between 30 December 2014 and 9 May 2015. The control was a widely used simple linctus (SL) medicine available for acute cough in the UK. The investigators were blinded to the nature of the investigational product by using identical sealed packaging for both medicines. Participants self-administered their assigned medication outside the pharmacy or GP surgery.

Participants

Participants aged ≥18 years who self-referred themselves to a GP or pharmacist with an acute cough of <7 days' duration were recruited. Participant inclusion criterion was a severity of at least 60 mm on a 0–100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS). Participant exclusion criteria were (1) participants with a chronic cough, (2) current or history of smoking within the past 12 months (including e-cigarettes), (3) participants with any relevant hospital stay of >2 days within a 6-month period, (4) use of any cough or cold treatment for the current cough episode, including antibiotics, (5) productive cough with excessive secretion, (6) use of ACE inhibitors medication.

Participant involvement

Participants were not involved in the design or conduct of this study.

Ethics and trial registration

The trial protocol was registered prior to starting the study in the publically available EudraCT database (reference: 2014-004255-31) and no protocol amendments were made subsequently. All participants provided written informed consent.

Randomisation

All participants considered eligible for study participation and who signed a consent form were given a unique randomisation number based on a predefined computer-generated randomisation scheme corresponding to a sealed medication pack that contained either CS1002 (2×150 mL) or SL (2×150 mL). Participants were allocated treatment using a block randomisation with a block size of 4.

Study medication

Participants were randomised to one of the following treatments:

CS1002 (Unicough): diphenhydramine 14 mg/5 mL, levomenthol 1.1 mg/5 mL and ammonium chloride 135 mg/5 mL in a cocoa-based demulcent preparation.

SL: citric acid monohydrate 125 mg/5 mL in a syrup base.

Interventions

The participants were approached, screened, consented and randomised during their initial consultation with their GP or the pharmacist. Participants took their study medication orally four times daily (5 mL in the morning, 5 mL at lunchtime, 10 mL at teatime and 10 mL at bedtime) for up to 7 days. Participants were instructed to take the medication regularly until the cough resolved.

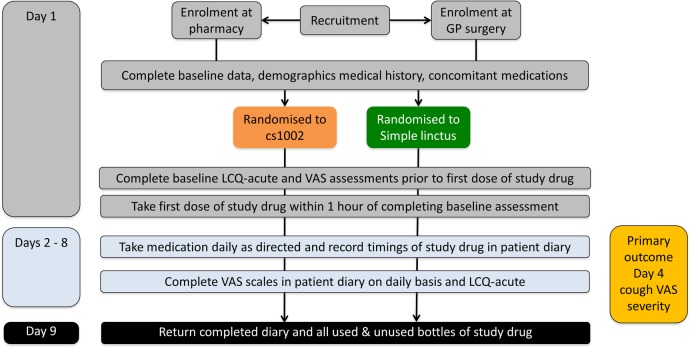

Methods of evaluation

Participants completed their assessments and compliance with medication in a daily diary. Each participant received a tamper-evident unidentifiable patient pack which was only opened on leaving the site. On completion, the pack was returned in a resealed and unidentifiable state. An independent data management organisation was used for data entry and to manage adverse event (AE) reporting. The investigators were blinded to the assignment of treatment and to the outcome assessments. The schedule of study visits is presented in figure 1. The participants were asked to complete assessments at baseline (day 1) and then at the same time of day from day 2–8. The study evaluated the efficacy of the study medications by assessing various aspects of acute cough.12 Cough severity, frequency and impact on sleep disruption in the previous 24 hours were assessed using a VAS. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed using the Leicester Cough Questionnaire for acute cough (LCQ-acute).3 13 The LCQ is a valid and reliable health status measure of acute cough in adults and is responsive to change. It comprises 19 items divided into three domains (physical, psychological and social) and uses a seven-point Likert response scale. A higher score indicates a better health status. The LCQ is designed for self-administration and takes <5 min to complete.3 14

Figure 1.

Study design. GP, general practitioner; LCQ-acute, Leicester Cough Questionnaire; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Primary efficacy end point

The primary efficacy end point was change from baseline to day 4 (ie, after 3 complete days of treatment) in cough severity on a 100 mm VAS (ranging from 0=no cough to 100=worst cough ever).

Secondary efficacy end points

The following prespecified end points were evaluated: (1) change from baseline in cough severity VAS at days 6 and 8; (2) change from baseline in cough frequency and cough sleep disruption VAS at days 4, 6 and 8; (3) time to resolution of cough symptoms, defined as the day at which cough severity VAS<17 mm (the threshold considered to be of minimal severity and the minimally important difference (MID) in acute cough);12 (4) change from baseline in LCQ-acute score at days 4, 6 and 8.

Safety monitoring

Participants were advised to reduce the dose of medication if they experienced drowsiness, and to document this in their daily diary. If drowsiness persisted, they were advised to discontinue the medication. Participants were advised to contact their doctor or a 24-hour help line if they felt unwell. Safety was assessed in terms of the frequency and severity of AEs occurring during the study and this was recorded by the investigator.

Statistical analysis and sample size

The sample size calculation was based on a difference in the change in cough severity VAS of 17 mm between participants treated with CS1002 and SL. Evaluation of the VAS in acute cough has suggested that the MID is 17 mm.12 It was estimated that ∼180 participants would be required to achieve a power of 90% to detect a difference between the treatment groups of 17 mm, with an SD of 35 mm.12

The primary analysis was conducted on the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, comprising all randomised participants who were treated with at least one dose of study medication and provided a baseline and at least one on-treatment assessment of cough severity. No imputation was used for missing data (ie, only observed data were used). A mixed model for repeated measures analysis was used to compare the effect of study treatments on cough parameters from baseline. The model included effects for treatment group, day, pooled centre, baseline cough severity, and treatment-by-day and baseline-by-day cough severity interaction terms. Residual plots and a normality test were used to assess normality. The results were also repeated for the per-protocol set (PPS), defined as participants in the ITT population who did not have an important protocol violation. A sensitivity analysis was also conducted to assess the robustness of the primary efficacy results to the method of handling missing data, using a last observation carried forward approach and a baseline observation carried forward approach for participants with no on-treatment data. Parametric data were presented as mean and either SD, SEM or 95% CIs. Statistical significance was defined as p≤0.05. The proportions of participants with cough resolution were compared using a stratified (by centre) Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test. Time-to-event analysis using a Cox proportional hazards model stratified by centre was used to estimate a HR.

Results

Participants

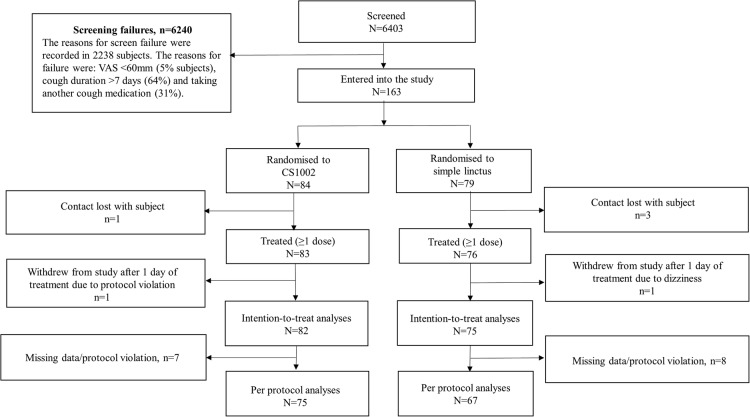

A total of 163 participants were randomised into the study at 4 GP sites and 14 pharmacy sites. The reasons for screening failures are shown in figure 2. The ITT population comprised 157 participants (82 CS1002, 75 SL), and the PPS comprised 142 participants (75 CS1002, 67 SL; figure 2). The baseline characteristics of both treatment groups were well matched (table 1). The mean age of the participants was 38 years, 57% of participants were female and 62% of participants were white (34% Asian and 4% black). The groups were well matched for the proportion of participants describing the characteristics of their cough as dry (CS1002 50%; SL 52%), chesty (CS1002 29%; SL 31%) or tickly (CS1002 21%; SL 17%).

Figure 2.

Trial CONSORT flow diagram. VAS, visual analogue scale.

Table 1.

Participant demographic and baseline characteristics

| CS1002 n (%) N=82 |

Simple linctus n (%) N=75 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Gender (N (%)) | ||

| Male | 34 (42) | 34 (45) |

| Female | 48 (59) | 41 (55) |

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 38.5 (17.3) | 38.2 (16.6) |

| Median (range) | 31.5 (18, 75) | 34.0 (18, 86) |

| Type of referral (N (%)) | ||

| GP | 30 (37) | 27 (36) |

| Pharmacist | 52 (63) | 48 (64) |

| Smoking status (N (%)) | ||

| Never smoked | 64 (78) | 54 (72) |

| Ex-smoker | 18 (22) | 21 (28) |

| Cough characteristics, mean (SD) | ||

| Cough duration (days) | 3.0 (1.5) | 3.1 (1.6) |

| Cough severity VAS (mm) | 80.4 (10.1) | 81.6 (9.9) |

| Cough frequency VAS (mm) | 79.5 (16.1) | 76.7 (15.5) |

| Cough sleep disruption VAS (mm) | 75.5 (23.2) | 64.6 (29.2) |

| LCQ-acute scores, mean (SD) | ||

| Total score | 10.8 (3.5) | 11.4 (3.2) |

| Physical score | 3.7 (1.2) | 4.1 (1.1) |

| Psychological score | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.9 (1.1) |

| Social score | 3.4 (1.4) | 3.5 (1.3) |

Based on ITT population.

GP, general practitioner; ITT, intention-to-treat; LCQ, Leicester Cough Questionnaire; VAS, visual analogue scale (using a scale of 0–100 mm).

Exposure

Participants took CS1002 medication for a mean (SD) of 6.2 (2.1) days and SL medication for 6.6 (1.8) days. The mean number of doses of study medication were 22.2 (8.7) for the CS1002 group and 23.7 (8.3) in the SL group. The maximum number of medication doses possible during the study was 28. The weight of the bottles of treatment returned at the end of study was planned to be used to estimate compliance, excluding doses not taken due to early termination from the study due to recovery. The weight of medicine broadly agreed with self-reported consumption stated by participants receiving CS1002, with a mean (SD) of 94% (17%) vs 94% (18%) for participants receiving SL.

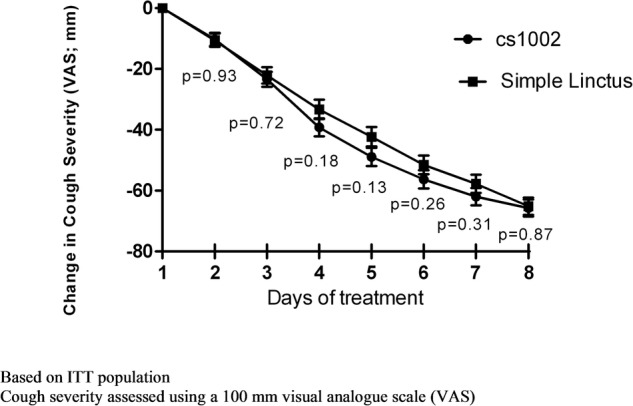

Primary efficacy end point

There was a clinically meaningful improvement in cough severity VAS at day 4 in both groups (table 2 and figure 3). The magnitude of the reduction in cough severity score was greater in the CS1002 group compared with the SL group but was not statistically significant; mean (95% CI) difference of −5.9 mm (−14.4 to 2.7), p=0.18. The PPS and ITT sensitivity analyses with imputations were also consistent with this finding (see online supplementary file).

Table 2.

Analysis of key efficacy parameters at day 4

| Key efficacy assessments | CS1002 | Simple linctus |

|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 82 | 75 |

| Cough severity | ||

| Baseline value (mean±SD) | 80.4 (10.1) | 81.6 (9.9) |

| Change from baseline to day 4: mean ( 95% CI) | −38.9 (−45.2 to −33.2) | −32.8 (−39.6 to −27.0) |

| Adjusted mean difference (95% CI) | −5.9 (−14.4 to 2.7) | |

| p Value (between groups) | p=0.18 | |

| Cough frequency | ||

| Baseline value (mean±SD) | 79.5 (16.1) | 76.7 (15.5) |

| Change from baseline to day 4: mean ( 95% CI) | −40.7 (−46.0 to −34.6) | −32.1 (−38.1 to −26.4) |

| Adjusted mean difference (95% CI) | −8.1 (−16.2 to 0.1) | |

| p Value (between groups) | p=0.05 | |

| Cough resolution | ||

| Day 4 value (n, %) | 24 (29.3%) | 13 (17.3) |

| Difference (%) | 12% | |

| p Value (between groups) | p=0.08 | |

| Sleep disruption | ||

| Baseline value (mean±SD) | 75.5 (23.2) | 64.6 (29.2) |

| Change from baseline to day 4; mean ( 95% CI) | −42.8 (−46.9 to −34.4) | −26.3 (−35.5 to −22.6) |

| Adjusted mean difference (95% CI) | −11.6 (−20.6 to −2.7) | |

| p Value (between groups) | p=0.01 | |

Based on intention-to-treat (ITT) population.

Negative values indicate a reduction in cough symptoms.

Adjusted mean difference, difference in between group differences. Cough severity, frequency and sleep disruption measured on a visual analogue scale (0-100 mm) Bold signifies p values.

Figure 3.

Change in cough severity over time. ITT, intention-to-treat.

bmjopen-2016-014112supp.pdf (177KB, pdf)

Secondary efficacy end points

Cough severity: There was a progressive decrease in cough severity VAS over the study, with the CS1002 group reporting a greater reduction compared with the SL group between days 3 and 7 (figure 3). The between group changes in cough severity VAS did not achieve statistical significance (mean (95% CI) difference of −4.2 mm (−12.2 to 3.9), p=0.31 at day 7; table 2 and figure 3).

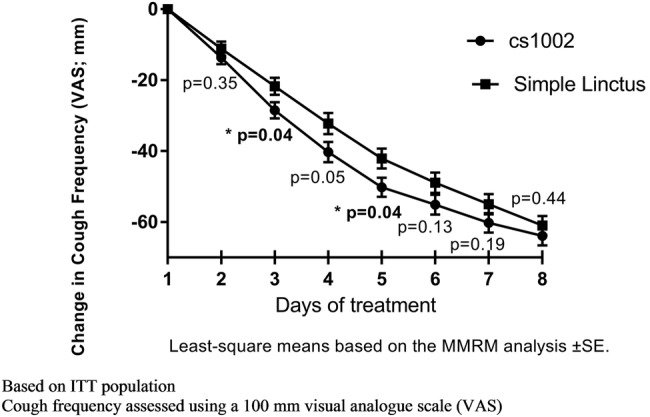

Cough frequency: There was a greater reduction in cough frequency VAS with CS1002 compared with SL at all time points (figure 4). At Day 4, there was an −8.1 mm (95% CI −16.2 to 0.1) greater reduction in cough frequency VAS for CS1002 compared with SL (p=0.05; table 2 and figure 4).

Figure 4.

Change in cough frequency over time. ITT, intention-to-treat; MMRM, mixed model for repeated measures.

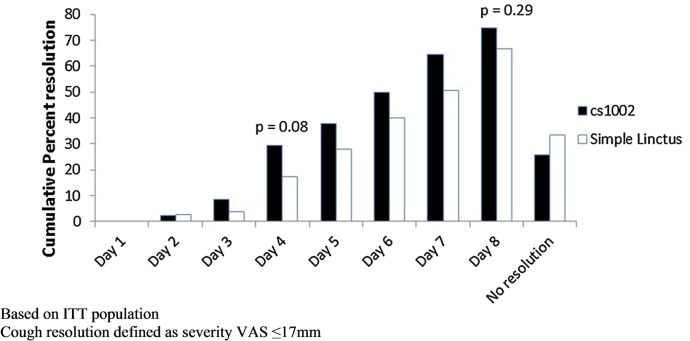

Cough resolution: By day 4, 29.3% of participants in the CS1002 group had achieved cough resolution compared with 17.3% in the SL group (p=0.08; table 2). There was no significant difference between the treatment groups regarding median time taken to achieve cough resolution (CS1002 6.5 days, SL 7.0 days, HR 1.300, p=0.20, figure 5). In a post hoc analysis, 20 participants (24.4%) in the CS1002 group and 10 (10.7%) in SL group stopped treatment by day 4 due to improvement in cough (p=0.02).

Figure 5.

Resolution of cough: cumulative percentage of participants. ITT, intention-to-treat; VAS, visual analogue scale.

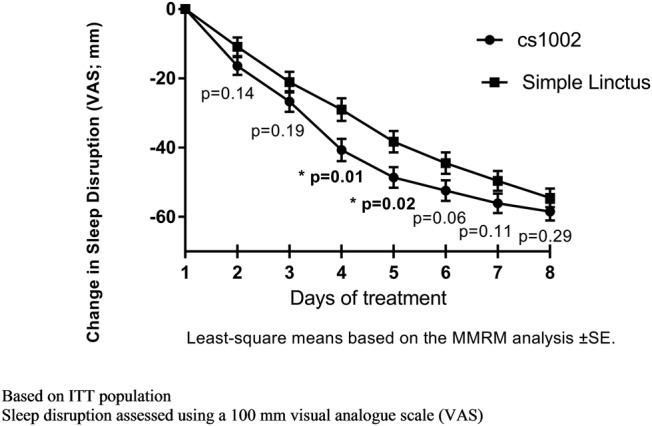

Sleep disruption: There was a greater reduction in sleep disruption with CS1002 compared with SL at all time points (figure 6). At day 4, the magnitude of reduction in cough sleep disruption score was greater for the CS1002 group than for the SL group, mean difference of −11.6 mm (95% CI −20.6 to −2.7), p=0.01 (figure 6 and table 2). A summary of all VAS results is provided in online supplementary figure S1.

Figure 6.

Change in cough sleep disruption over time. ITT, intention-to-treat; MMRM, mixed model for repeated measures.

Health-related quality of life: LCQ-acute total scores increased over time for both treatment groups, indicating an improvement in HRQoL. At day 6, the magnitude of the improvement was significantly greater in the CS1002 group compared with the SL group (mean difference 1.21 (95% CI 0.05 to 2.36), p=0.04; see online supplementary figures S2 and S3).

Adverse events

AEs were reported for 17 participants (20.5%) in the CS1002 group and 21 participants (27.6%) in the SL group during the study (table 3). The AEs were generally indicative of the study indication or likely to be associated with URTI, with the majority being mild or moderate severity. Events classified as severe were only seen in the SL treatment group, and comprised cough, sneezing and joint swelling (all occurring in one participant each). No SAEs or deaths were reported. There were no AEs of drowsiness reported during the study. Six participants (7%) in the CS1002 group and no participants in the SL group reported in their diary that they reduced the dose of medication due to drowsiness/tiredness. These events were not reported by the participants as AE. Following the reduction of the dose of medication, there were no further reports of drowsiness or tiredness.

Table 3.

Adverse events (AEs)

| CS1002 N=83 |

Simple linctus N=79 |

|

|---|---|---|

| AEs, n (%) | Total N (%) | Total N (%) |

| Number of participants with an AE | 17 (20.5) | 21 (27.6) |

| Nervous system disorders | 7 (8.4) | 10 (13.2) |

| Headache | 5 (6.0) | 9 (11.8) |

| Dizziness | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.6) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 8 (9.6) | 9 (11.8) |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 2 (2.4) | 4 (5.3) |

| Cough | 2 (2.4) | 3 (3.9) |

| Productive cough | 3 (3.6) | 1 (1.3) |

| Dyspnoea | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.6) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 5 (6.0) | 2 (2.6) |

| Diarrhoea | 3 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 2 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 0 (0.0) | 5 (6.6) |

| Pain | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.9) |

| Fever | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.6) |

| Infections and infestations | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.6) |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.6) |

Treated set population. AEs reported for >1 participant.

Discussion

This multicentre, randomised study compared the efficacy and safety of two OTC cough mixtures: CS1002 containing diphenhydramine, ammonium chloride and levomenthol in a cocoa-based demulcent preparation versus SL containing citric acid monohydrate. This is one of the largest multiple dosing, randomised controlled trials in participants with URTI-associated cough to date, and the first to recruit participants seeking cough medicines at pharmacies. The study did not achieve a significant reduction in primary end point cough severity after 3 days of treatment, but there were greater reductions in cough frequency and sleep disruption and resolution of cough in participants receiving CS1002 compared with SL.

Our trial represents a significant advance in the study of URTI-associated cough for a number of reasons. A Cochrane systematic review of cough medicines concluded that there was no evidence for or against cough medicines for URTI-associated cough.6 Previous trials of cough medicines have been hampered by the recruitment of small numbers of participants, the recruitment of participants not representative of URTI-associated cough, uncontrolled study design and the use of unvalidated end points. We conducted a randomised clinical trial that included validated cough outcome measures. Our primary outcome measure, the VAS, is widely used in studies of cough.15 We recruited participants with an URTI-associated cough who were otherwise healthy and seeking an antitussive medicine. Our participants were unselected for the category of cough, and included a broad range of participants with self-reported dry, chesty and tickly cough. We conducted a large study, recruiting participants from 18 sites. This is the first study to recruit participants presenting to pharmacies, and therefore the study population is more likely to resemble the broader population seeking cough medicines. There were few participants that dropped out of the trial, and therefore our data completeness was good. The efficacy of the interventions was evaluated with widely used and validated end points of cough severity VAS and LCQ-acute HRQoL questionnaires.15 16 We conducted a controlled trial and the comparator was a widely used OTC treatment. SL, which costs less than many OTC medicines to purchase but like most cough medicines, it lacks a strong evidence base. Its efficacy has not been compared with natural recovery, placebo or to other cough medicines. The rate of reduction of cough severity VAS associated with SL in our study does appear to be greater than that reported for natural recovery.12 The mechanism of action of SL is poorly understood, but is thought to be related to a demulcent effect and the hypersalivation resulting from the sugary taste.11

There was a clinically significant reduction in primary end point cough severity VAS at day 4 in both groups. However, CS1002 did not achieve the primary end point of a greater reduction in cough severity at day 4 compared with SL. There were, however, greater reductions in secondary end points of sleep disruption and cough frequency, and improvements in HRQoL associated with CS1002 compared with SL. There was also a trend favouring greater resolution of cough at day 4 with CS1002 compared with SL, with a near doubling of the proportion of participants whose cough had resolved. This was supported by a post hoc analysis that found a significantly greater number of participants had discontinued their medication due to resolution of cough by day 4 (CS1002, 24.4% vs SL, 10.7%: p=0.02). The MID for cough outcome measures of frequency VAS, sleep disruption VAS and cough resolution have not been reported in URTI-associated cough, and this should be studied in future to facilitate the clinical interpretation of data. CS1002 was well tolerated, and there were few significant AEs, including drowsiness. Drowsiness was managed with dose reduction, and no participants discontinued the medication because of this symptom. Participants were compliant with both medications, and this was verified by counting the doses of medication returned at the end of the study. The mechanism of action of CS1002 is poorly understood. There are a number of possibilities, which include a reduction in cough reflex sensitivity,7 promotion of more restful sleep and a demulcent action. CS1002 contains a cocoa-flavoured demulcent that is more viscous than most available OTC cough medicines, and this may potentially promote palatability.

There are a number of important limitations with our study. We did not use a placebo comparator, and the study was not double-blinded. The limitations of a single-blinded study were reduced by informing the participants that they were going to receive a cough medicine, but not the characteristics of the medicine. The investigators were blinded to the study because both medicines were contained in identical packaging, and participants were instructed to start their medication outside the pharmacy or GP clinic. We used SL as the comparator since this is a widely used cough treatment. It is possible that there may have been greater differences in efficacy outcome measures if we had used an inactive placebo. Another option for comparator that should be considered in future studies is the demulcent used in CS1002. It is likely that there was also significant natural recovery in our study. Our data highlight the difficulty in evaluating cough medicines in a rapidly resolving condition. We do not know whether the cough at study entry was worsening or improving and this could have impacted on our findings. We were short of our recruitment target of 180 participants; we recruited 163 participants. This was due to a delay in the start of the study, and consequently a reduced time window for recruitment during the cough and cold winter season. We think it is unlikely that the slight under-recruitment of participants would have altered our study conclusions. The reasons for screen failures were not recorded for many patients, particularly at busy pharmacy sites. The reasons were, however, recorded for 2238 participants and suggest that a large number of participants approached had duration of cough >7 days. It is possible that the discontinuation of medication could have reflected lack of efficacy as well as recovery. We did not investigate the cause of the acute cough, and future studies should possibly assess viruses, pertussis and bacterial causes. We did not assess cough with objective outcome measures, such as cough frequency monitoring.16 Recently, there have been significant advances in cough monitoring technology, and this should be possible in future studies.17

In conclusion, the OTC cough medicine CS1002 did not achieve a significant reduction in the primary end point cough severity, but it was associated with a greater reduction in cough frequency and sleep disruption, and increased resolution of cough leading to early discontinuation of medication and improved HRQoL compared with comparator SL. Further studies should investigate the impact of natural recovery and placebo on cough outcome measures to facilitate the optimal study protocol in URTI-associated cough.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge all the doctors and pharmacists who recruited participants for this study: Dr Mark Blagden, Ashgate Medical Practice, Chesterfield; Dr Naseem Gill, CH Medical, Oldham; Dr Paula Evans, Acomb Surgery, York; Dr Mark Roman, Woodthorpe Surgery, York; Dr Astrid Henckel, Monkgate Surgery, York; Maimuna Sultana, Peak Pharmacy, Manchester; Amanda Gilchrist, Peak Pharmacy, Cheadle; Deborah Kelly, Tims and Parker, Manchester; Jonathan Hill, Peak Pharmacy, Manchester; Anthony Parker, Tims and Parker, Manchester; Rahbeia Najeeb, Peak Pharmacy, Manchester; Johanne Nesbit, Davey's Pharmacy, Liverpool; Manjeet Patter, Jhoots Pharmacy, Darlaston; Keval Jagatiya, Jhoots Pharmacy, Dudley; Rumeesha Damaree, Jhoots Pharmacy, Rowley Regis; Rashimi Sharma, Jhoots Pharmacy, Wolverhampton; David Meddings, Jhoots Pharmacy, Rowley Regis; David Bott, Jhoots Pharmacy, Cradley Heath; Aasma Ahmed, Jhoots Pharmacy, Birmingham; Fezza Hassan, Jhoots Pharmacy, Birmingham; Kiranjit Sidhu, Jhoots Pharmacy, Birmingham; Indira Panchal, Meiklejohn Pharmacy, Bedford; Mohammed Fahim, Wexham Road Pharmacy, Slough; Zahoor Sharif, Oxford Road Pharmacy, Reading. Medical writing support was provided by Debbie Jordan, with funding provided by Infirst Healthcare. Medical safety monitoring was conducted by Dr Sunita Chauhan, Pharsafer.

Footnotes

Contributors: SB, JB, AK, VE, RW and AM were involved in conception and design of work. RW, VE and JB were involved in data analysis. All authors were involved in data interpretation. SB was involved in drafting the manuscript with input from JB, AK, VE, RW and AM. All authors were involved in review and approval of the manuscript.

Funding: The study was funded by Infirst Healthcare and Infirst Healthcare is the manufacturer of CS1002 (Unicough).

Competing interests: SSB has received personal fees from Infirst Healthcare during the conduct of the study for advisory work. AHM has received personal fees from Infirst Healthcare during the conduct of the study for advisory work. JB, VE and TK are employees of Infirst Healthcare. RW is a statistical consultant to Infirst Healthcare.

Ethics approval: North West—Greater Manchester South Research Ethics Committee (Reference: 14/NW/1424).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Proprietary Association of Great Britain (PAGB). Self Care Forum cough fact sheet. http://www.selfcareforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/7-Cough.pdf (accessed Mar 2016).

- 2.Morice AH, McGarvey L, Pavord I, British Thoracic Society Cough Guideline Group . Recommendations for the management of cough in adults. Thorax 2006;61(Suppl 1):i1–24. 10.1136/thx.2006.065144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birring SS, Prudon B, Carr AJ et al. . Development of a symptom specific health status measure for patients with chronic cough: Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ). Thorax 2003;58:339–43. 10.1136/thorax.58.4.339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dicpinigaitis PV, Colice GL, Goolsby MJ et al. . Acute cough: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Cough 2009;5:11 10.1186/1745-9974-5-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sales value of over-the-counter (OTC) cough/cold/sore throat medicines in Great Britain in 2014, by category (in millions GBP). http://www.statista.com/statistics/415982/over-the-counter-sales-for-cough-cold-sore-throat-in-great-britain/ (accessed Mar 2016).

- 6.Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T. Over-the-counter (OTC) medications for acute cough in children and adults in ambulatory settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;8:CD001831 10.1002/14651858.CD001831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dicpinigaitis PV, Dhar S, Johnson A et al. . Inhibition of cough reflex sensitivity by diphenhydramine during acute viral respiratory tract infection. Int J Clin Pharm 2015;37:471–4. 10.1007/s11096-015-0081-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eccles R. Menthol and related cooling compounds. J Pharm Pharmacol 1994;46:618–30. 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1994.tb03871.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morice AH, Marshall AE, Higgins KS et al. . Effect of inhaled menthol on citric acid induced cough in normal subjects. Thorax 1994;49:1024–6. 10.1136/thx.49.10.1024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Behera D. Textbook of pulmonary medicine. 2nd edn Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd, 2010:20. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eccles R. Mechanisms of the placebo effect of sweet cough syrups. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2006;152:340–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KK, Matos S, Evans DH et al. . A longitudinal assessment of acute cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:991–7. 10.1164/rccm.201209-1686OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yousaf N, Lee KK, Jayaraman B et al. . The assessment of quality of life in acute cough with the Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ-acute). Cough 2011;7:4 10.1186/1745-9974-7-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brignall K, Jayaraman B, Birring SS. Quality of life and psychosocial aspects of cough. Lung 2008;186(Suppl 1):S55–58. 10.1007/s00408-007-9034-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boulet LP, Coeytaux RR, McCrory DC et al. . Tools for assessing outcomes in studies of chronic cough: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2015;147:804–14. 10.1378/chest.14-2506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raj AA, Birring SS. Clinical assessment of chronic cough severity. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2007;20:334–7. 10.1016/j.pupt.2006.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birring SS, Fleming T, Matos S et al. . The Leicester Cough Monitor: preliminary validation of an automated cough detection system in chronic cough. Eur Respir J 2008;31:1013–18. 10.1183/09031936.00057407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014112supp.pdf (177KB, pdf)