Abstract

Objectives

Acute respiratory infections and fever among children are highly prevalent in primary care. It is challenging to distinguish between viral and bacterial infections. Norway has a relatively low prescription rate of antibiotics, but it is still regarded as too high as the antimicrobial resistance is increasing. The aim of the study was to identify predictors for prescribing antibiotics or referral to hospital among children.

Design

Secondary analysis of a randomised controlled study.

Setting

4 out-of-hours services and 1 paediatric emergency clinic in Norwegian primary care.

Participants

401 children aged 0–6 years with respiratory symptoms and/or fever visiting the out-of-hours services.

Outcomes

2 main outcome variables were registered: antibiotic prescription and referral to hospital.

Results

The total prescription rate of antibiotics was 23%, phenoxymethylpenicillin was used in 67% of the cases. Findings on ear examination (OR 4.62; 95% CI 2.35 to 9.10), parents' assessment that the child has a bacterial infection (OR 2.45; 95% CI 1.17 to 5.13) and a C reactive protein (CRP) value >20 mg/L (OR 3.57; 95% CI 1.43 to 8.83) were significantly associated with prescription of antibiotics. Vomiting in the past 24 hours was negatively associated with prescription (OR 0.26; 95% CI 0.13 to 0.53). The main predictors significantly associated with referral to hospital were respiratory rate (OR 1.07; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.12), oxygen saturation <95% (OR 3.39; 95% CI 1.02 to 11.23), signs on auscultation (OR 5.57; 95% CI 1.96 to 15.84) and the parents' assessment before the consultation that the child needs hospitalisation (OR 414; 95% CI 26 to 6624).

Conclusions

CRP values >20 mg/L, findings on ear examination, use of paracetamol and no vomiting in the past 24 hours were significantly associated with antibiotic prescription. Affected respiration was a predictor for referral to hospital. The parents' assessment was also significantly associated with the outcomes.

Trial registration number

NCT02496559; Results.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Nearly complete data since we used dedicated nurses to collect clinical symptoms and findings on all children.

Multiple explanatory variables collected on nearly all children.

Wide inclusion criteria showing the variety of diagnoses and conditions treated at OOH services.

Validity of diagnoses is weak in primary care and often not possible to verify.

This study is based on a randomised study where every third child got a C reactive protein (CRP) test. This may have resulted in more elevated CRP values than would otherwise have been found.

Introduction

Acute childhood infections are highly prevalent in primary care. Most infections are self-limiting and the prevalence of serious bacterial infections is decreasing,1 but still challenging to distinguish from self-limiting illness. One important reason for the decline in serious infections in Norway is vaccines. Haemophilus influenza type B (HIB) was the most frequent cause of meningitis, epiglottitis and other invasive infections in young children in Norway before the vaccine was introduced in the childhood immunisation schedule in 1992. After the vaccine was introduced, these infections practically disappeared. The annual incidence of invasive pneumococcal infections fell from 75 to around 10 cases per 100 000 after the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in 2006.2

There exists no decision score system for children for use in primary care. Pediatric Early Warning Score has been evaluated in hospitals, and this tool has been found valuable in quantifying patient status, early recognition of clinical deterioration and promoting communication.3 It has not been investigated for use in primary care where the prevalence of serious infections is lower. Other studies have shown the utility of a scoring system to stratify children with acute infections, but still there is a need of validation for use in primary care.4–6

Near patient testing in primary care has expanded in Norway as in other Scandinavian countries.7 The most used test is C reactive protein (CRP), an inflammation marker reflecting the severity of inflammation and tissue injury and used by many as a tool to differentiate between bacterial and viral infections. It has been popular in Norwegian primary care as a point-of-care test, used in more than 50% of all consultations with children with respiratory symptoms and infections.8 To order the test seems more like a routine than a supplement to history taking and clinical examination. It is possible that the test is used to assure parents that there is no serious bacterial infection. It is also possible that the widespread use may have economic reasons.9 The test result is difficult to interpret, especially for low values between 20 and 50 mg/L.10 11 Urine dipstick, haemoglobin and Strep A test are also available at most services. Strep-A test is recommended for differentiation between bacterial and viral throat infections.12 Measurement of oxygen saturation with pulse oximeters has been more available for children in emergency departments. Earlier studies have seen a connection with increased use and increased hospitalisation.13 How it affects the referral rate from primary care is not known.

Since 2010, the prescription rate of antibiotics has been relatively stable in Norway but decreased slightly in 2013–2014.14 In Scandinavia, Sweden has a lower prescription rate (13.0 DDD per 1000 inhabitants per day), while Denmark has the same rate as Norway (15.9 DDD per 1000 inhabitants per day).15 Still, the prescription rate is regarded as too high and it is a national strategy to try to reduce it by 20–30%.16 National guidelines for the use of antibiotics in primary care have been published from the Norwegian Directorate of Health.17 The guidelines are well known among primary care physicians, but it is not known to what extent they are followed.

Before admission to hospital in Norway, a patient must be evaluated by a general practitioner (GP) or at an out-of-hours service. In total 80% of all antibiotics are prescribed in primary care. To reduce the prescription rate and to properly select children in need of treatment at hospitals, we need to know more about what is predicting the two actions.

The aim of the present study was therefore to identify predictors for antibiotic prescription and referral to hospital in a primary care setting.

Method

We included children aged 0–6 years with fever and/or respiratory symptoms. The data consist of (1) clinical symptoms and signs collected by a nurse at the OOH services before the doctor's consultation, (2) the medical record and (3) a questionnaire filled in by the parents before the consultation. Every third child was randomised to a CRP test before the consultation. The remaining 2/3 received usual care, allowing the doctor to order a CRP test on individual indication. The results of the randomised trial have been reported elsewhere.18

Inclusion and procedures

The inclusion of participants took place during the winter seasons from January 2013 until May 2015 at four different OOH services near Bergen and at one paediatric emergency clinic at Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen. This emergency clinic is a walk-in, open-access facility, and is located at a hospital and staffed by paediatricians.

The nurses at the OOH services were informed about the study inclusion criteria and examination procedures. At the paediatric emergency clinic, two trained nurses were engaged especially for the project. The parents were approached by the nurse and invited to participate in the study and fill out a questionnaire prior to the consultation. The nurse did a clinical examination on all children and a CRP test on every third child. The CRP result followed the patient to the consultation. The diagnosis and treatment were recorded from the medical record after the consultation.

Variables

The two main outcome variables were antibiotic prescription and referral to hospital. Recorded variables from the medical history were age, gender, previous chronic disease, duration of present illness, fever in the past 24 hours, variation in fever, vomiting, earache, coughing, dyspnoea, throat symptoms, diarrhoea, reduced diuresis, cervical rigidity, skin rash, and use of paracetamol or ibuprofen in the past 24 hours. The parents' assessment of the illness and its seriousness was also recorded. Variables from the nurse's examination were temperature, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, the degree of hydration, capillary refill time and general condition on a three-point scale (normal, ill and severely ill). From the medical record, we noted signs on auscultation and at ear examination, if not mentioned in the record, it was coded as missing. Finally, we recorded whether the doctor was a paediatrician or working at the OOH services.

Statistical analysis

Means were analysed with Student's t-tests and proportions with χ2 tests. Logistic regression analyses were performed to analyse predictors for the two main outcomes: prescription of antibiotics and referral to hospital. Explanatory variables significant (p<0.05) in bivariate analyses were included in the final regression model. All variables with missing values were imputed in the final model. Multiple imputations with a fully conditional specification method producing five imputed data sets were performed and the results pooled. Hosmer-Lemeshow tests were used to test the goodness-of-fit. Significance level was set at 5% (p<0.05). Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.23.

Results

A total of 401 children were recruited for the study, but 4 left the clinic before the doctor's consultation, leaving 397 for inclusion in our analyses. The mean age was 2.3 years (median 1.6), and 55.6% were boys.

Prescription of antibiotics

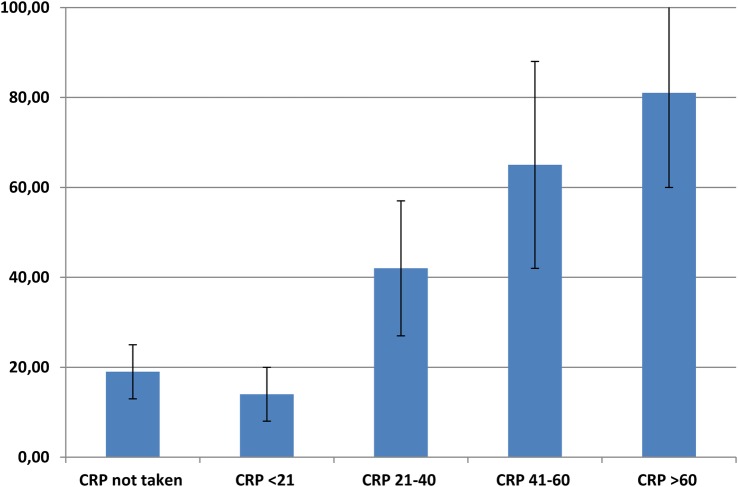

A total of 93 patients (23%) got a prescription of antibiotics. Phenoxymethylpenicillin (PcV) was used most often, and amoxicillin to a lesser extent (table 1). The distribution of diagnoses and prescriptions at different CRP levels is shown in table 2. In the group with CRP 21–40 mg/L, more than 40% got a prescription, compared with nearly all in the group with CRP>80 mg/L (figure 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of different types of antibiotics prescribed

| Antibiotics | Number | Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| Phenoxymethylpenicillin | 62 | 66.7 |

| Amoxicillin | 19 | 20.4 |

| Erythromycin (macrolide) | 8 | 8.6 |

| Clindamycin | 3 | 3.2 |

| Unknown | 1 | 1.1 |

| Total | 93 | 100 |

Table 2.

Distribution of diagnoses and number of AB prescriptions in different CRP value (mg/L) groups (%) (n=397)

| Diagnoses | Referral to hospital | AB | AB when CRP not taken | AB when CRP<21 | AB when CRP 21–40 | AB when CRP 41–60 | AB when CRP>60 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute tonsillitis (47) | 0 | 32 | 11 (69) | 5 (38) | 8 (89) | 3 (75) | 5 (100) |

| Otitis media (54) | 0 | 36 | 14 (58) | 10 (63) | 7 (78) | 3 (100) | 2 (100) |

| Pneumonia (15) | 5 | 10 | 1 (100) | 3 (100) | 1 (100) | 2 (100) | 3 (100) |

| URI (194) | 6 | 10 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (5) | 4 (44) | 3 (60) |

| Fever/cough/other (49) | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | – | 1 (100) | – |

| Asthma/bronchiolitis (31) | 11 | 4 | 2 (15) | 0 | 2 (100) | – | 0 |

| GE/dehydration (5) | 2 | 0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pyelonephritis (2) | 2 | 0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Total number in the group | 31 | 93 | 153 (19) | 132 (14) | 45 (42) | 20 (65) | 16 (81) |

AB, antibiotics; CRP, C reactive protein; GE, gastroenteritis; URI, upper respiratory infections.

Figure 1.

Antibiotic prescription rates (%) with 95% CI at different C reactive protein (CRP) levels (n=366).

For pneumonia, all got antibiotics if not referred to hospital. For the other diagnoses, there was a clear tendency that higher CRP led to a higher prescription rate. There was a discrepancy between earache and findings with otoscopy; 129 had signs of ear infection with otoscopy and 103 had earache, but only 63 had both. In total, 42% of all with signs of infection or earache got a diagnosis of otitis media and an antibiotic prescription.

If the parents thought it was a bacterial infection and that antibiotics were needed 39% got a prescription (table 3).

Table 3.

Parents' assessment and prescription of antibiotics and referral to hospital

| Variable | Prescription of antibiotics, number (%) | Referral to hospital, number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Parents' assessment of sickness | ||

| No opinion, n=177 | 34 (19) | 12 (7) |

| Viral infection, n=101 | 14 (14) | 12 (12) |

| Bacterial infection, n=116 | 45 (39) | 7 (6) |

| Parents' assessment of degree of seriousness | ||

| Think it is not serious but want a check, n=103 | 12 (12) | 3 (3) |

| Not sure, maybe in need of treatment, n=149 | 37 (25) | 15 (10) |

| Think antibiotics are needed, n=134 | 44 (33) | 6 (5) |

| Think the child needs hospitalisation, n=7 | 0 | 6 (86) |

Referrals

A total of 31 patients (8%) were referred to hospital. The most common diagnoses among the referred patients were asthma, bronchiolitis and pneumonia. Two had gastroenteritis and two had pyelonephritis (table 2). If the parents assessed the child to need hospitalisation 86% were referred to hospital (table 3).

Predictor analyses

Explanatory variables significant in bivariate analyses are shown in table 4. Ear examination was missing in 17% of cases, oxygen saturation in 14% of all cases, and the remainder in <10%. Imputed variables were: vomiting, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, findings on auscultation and ear examination, parents' assessment, earache, use of paracetamol and temperature measurement.

Table 4.

Prescription of antibiotics and referral to hospital in different groups (bivariate analyses)

| Prescription of antibiotics |

Referral to hospital |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N | Yes | No | p Value | Yes | No | p Value |

| Means | |||||||

| Age | 397 | 2.61 | 2.25 | 0.098 | 1.69 | 2.39 | 0.040 |

| Temperature measured | 385 | 38.22 | 37.92 | 0.013 | 38.19 | 37.98 | 0.245 |

| Respiratory rate | 365 | 31.11 | 33.08 | 0.246 | 48.28 | 31.30 | <0.001 |

| Proportions | |||||||

| CRP value (mg/L) | 397 | ||||||

| Not taken | 164 | 0.18 | 0.82 | 0.07 | 0.93 | ||

| CRP<21 | 142 | 0.13 | 0.87 | 0.07 | 0.93 | ||

| CRP 21–40 | 48 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.06 | 0.94 | ||

| CRP 41–60 | 22 | 0.59 | 0.41 | 0.09 | 0.91 | ||

| CRP>60 | 21 | 0.62 | 0.38 | <0.001 | 0.24 | 0.76 | 0.089 |

| Oxygen saturation | 340 | ||||||

| >95% | 227 | 0.22 | 0.78 | 0.05 | 0.95 | ||

| 90–95% | 104 | 0.21 | 0.79 | 0.13 | 0.87 | ||

| <90% | 9 | 0.22 | 0.78 | 0.984 | 0.33 | 0.67 | 0.001 |

| Parents’ assessment of seriousness | 393 | ||||||

| Think it is not serious but want a check | 103 | 0.12 | 0.88 | 0.03 | 0.97 | ||

| Not sure, maybe in need of treatment | 149 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.10 | 0.90 | ||

| Think antibiotics are needed | 134 | 0.33 | 0.67 | 0.05 | 0.95 | ||

| Think the child needs hospitalisation | 7 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.86 | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| Parents’ assessment of sickness | 394 | ||||||

| No opinion | 177 | 0.19 | 0.81 | 0.07 | 0.93 | ||

| Viral infection | 101 | 0.14 | 0.86 | 0.12 | 0.88 | ||

| Bacterial infection | 116 | 0.39 | 0.61 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.215 |

| Paediatrician | 167 | 0.18 | 0.82 | 0.09 | 0.91 | ||

| Doctors working at OOH services | 230 | 0.27 | 0.73 | 0.029 | 0.07 | 0.93 | 0.458 |

| Vomiting on last day | 242 | 0.16 | 0.84 | 0.12 | 0.88 | ||

| Not vomiting on last day | 153 | 0.29 | 0.71 | 0.003 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.021 |

| Earache in the past 24 hours | 103 | 0.42 | 0.58 | 0.05 | 0.95 | ||

| No earache in the past 24 hours | 290 | 0.17 | 0.83 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.184 |

| Dyspnoea in the past 24 hours | 225 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.11 | 0.89 | ||

| No dyspnoea in the past 24 hours | 171 | 0.21 | 0.79 | 0.522 | 0.04 | 0.96 | 0.052 |

| Paracetamol in the past 24 hours | 264 | 0.30 | 0.70 | 0.08 | 0.92 | ||

| No use of paracetamol in the past 24 hours | 131 | 0.10 | 0.90 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.92 | 0.775 |

| Findings on ear examination | 129 | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.02 | 0.98 | ||

| No findings on ear examination | 200 | 0.14 | 0.86 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.90 | 0.011 |

| Signs on auscultation | 83 | 0.22 | 0.78 | 0.24 | 0.76 | ||

| No signs on auscultation | 281 | 0.21 | 0.79 | 0.837 | 0.04 | 0.96 | <0.001 |

| Randomised to CRP pretest test | 138 | 0.26 | 0.74 | 0.05 | 0.95 | ||

| Randomised to usual care | 259 | 0.22 | 0.78 | 0.362 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.139 |

CRP, C reactive protein.

Prescription of antibiotics

Findings on ear examination, use of paracetamol and no vomiting in the past 24 hours all remained significantly associated with prescription of antibiotics in the multiple regression analysis after multiple imputations (table 5). CRP>20 mg/L was significantly associated with prescription. The parents' assessment that their child had a bacterial infection was also associated with increased prescription rate. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test for this analysis showed good fitness of the model with p=0.540 before imputation and p=0.805 after imputation.

Table 5.

OR for prescribing antibiotics by different variables and parents' assessment. Significant results (p<0.05) in bold

| Complete case, n=294 (missing 26%) |

Multiple imputation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Temperature measured* | 1.14 | 0.78 to 1.66 | 1.11 | 0.78 to 1.57 |

| Paediatrician (no=0, yes=1) | 0.73 | 0.33 to 1.61 | 0.83 | 0.43 to 1.62 |

| Vomiting on last day (no=0, yes=1) | 0.26 | 0.11 to 0.60 | 0.26 | 0.13 to 0.53 |

| Earache in the past 24 hours (no=0, yes=1) | 1.41 | 0.66 to 3.03 | 1.71 | 0.89 to 3.28 |

| Findings on ear examination (no=0, yes=1) | 4.22 | 1.98 to 9.00 | 4.62 | 2.35 to 9.10 |

| Signs on auscultation (no=0, yes=1) | 1.62 | 0.64 to 4.10 | 1.57 | 0.68 to 3.63 |

| Paracetamol in the past 24 hours | 2.13 | 0.88 to 5.13 | 2.35 | 1.11 to 4.96 |

| CRP value (mg/L) | ||||

| Not taken (reference) | ||||

| CRP<21 | 0.66 | 0.27 to 1.63 | 0.71 | 0.33 to 1.55 |

| CRP 21–40 | 3.39 | 1.22 to 9.43 | 3.57 | 1.43 to 8.83 |

| CRP 41–60 | 13.32 | 3.39 to 52.37 | 10.11 | 3.07 to 33.34 |

| CRP>60 | 11.33 | 2.84 to 45.12 | 10.19 | 2.84 to 36.49 |

| Parents' assessment of seriousness | ||||

| Think it is not serious but want a check (reference) | ||||

| Not sure, maybe in need of treatment | 1.38 | 0.49 to 3.89 | 1.27 | 0.52 to 3.12 |

| Think antibiotics are needed | 1.63 | 0.56 to 4.75 | 1.41 | 0.55 to 3.62 |

| Think the child needs hospitalisation | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.00 |

| Parents' assessment of sickness | ||||

| No opinion (reference) | ||||

| Viral infection | 0.73 | 0.28 to 1.93 | 0.89 | 0.38 to 2.10 |

| Bacterial infection | 1.78 | 0.79 to 4.01 | 2.45 | 1.17 to 5.13 |

Adjusted logistic regression with and without multiple imputation.

*Continuous variable.

CRP, C reactive protein.

Referrals

The strongest predictor for referral to hospital was affected respiration. No findings on ear examination, a high respiratory rate, obstructive signs on auscultation and reduced oxygen saturation were significantly associated with referral to hospital, as well as the parents' assessment of disease severity (table 6). All remained significant after imputation. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was significant before imputation (p=0.006) but not after (0.105), showing that the model with imputation gave the best fit.

Table 6.

OR for referral to hospital by different variables and parents' assessment. Significant results (p<0.05) in bold

| Complete cases n=245 (missing 38%) |

Multiple imputation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Age* | 1.30 | 0.87 to 1.94 | 1.02 | 0.71 to 1.46 |

| Vomiting (no=0, yes=1) | 0.85 | 0.23 to 3.18 | 1.09 | 0.40 to 2.97 |

| Respiratory rate* | 1.05 | 1.00 to 1.11 | 1.07 | 1.03 to 1.12 |

| Oxygen saturation | ||||

| >95% (reference) | ||||

| 90–95% | 4.28 | 1.05 to 17.43 | 3.39 | 1.02 to 11.23 |

| <90% | 16.03 | 0.96 to 267.81 | 3.19 | 0.32 to 31.94 |

| Signs on auscultation (no=0, yes=1) | 6.92 | 1.73 to 27.64 | 5.57 | 1.96 to 15.84 |

| Findings on ear examination (no=0, yes=1) | 0.19 | 0.04 to 0.98 | 0.22 | 0.05 to 0.87 |

| Parents' assessment of seriousness | ||||

| Think it is not serious but want a check (reference) | ||||

| Not sure, maybe in need of treatment | 14.61 | 1.13 to 188.48 | 6.37 | 1.34 to 30.18 |

| Think antibiotics are needed | 7.08 | 0.52 to 96.80 | 3.80 | 0.73 to 19.84 |

| Think the child needs hospitalisation | 815.72 | 26.58 to 25033.0 | 414.17 | 25.89 to 6624.4 |

Adjusted logistic regression with and without multiple imputation.

*Continuous variable.

Discussion

Summary

According to Norwegian guidelines, the preferred antibiotic for respiratory tract infections is PcV. This study showed this drug to be used for 2/3 of all children treated with antibiotics. CRP values >20 mg/L, use of paracetamol in the past 24 hours and signs on ear examination were the main predictors of antibiotic prescription. Increased respiratory rate and signs on auscultation were significantly associated with hospital referrals. Parents' assessments of sickness and seriousness were also significantly associated with outcomes. The prescription rate increased already with CRP values >20 mg/L, not according to the national guidelines which recommend clinical observations when CRP values are <50–100 mg/L.

Strengths and limitations

Our data are nearly complete due to the effort of the nurses. Collecting data from the medical record alone would have been simpler and may have increased the number of included children, but would have caused more missing data.

The children who were seen by a paediatrician at the paediatric emergency clinic were unselected and not referred from primary care. At the OOH services, the doctor is a GP, a GP in training or other specialists or locums. We have no detailed information about the experience of these OOH doctors, but know that younger doctors are working more often at OOH-services and make more use of CRP.9 How the experience affects prescription is not known, but in our study we did not find a significant association between being a paediatrician and prescription.

Validity of diagnoses is weak in primary care and often not possible to verify. Many use symptom diagnoses as fever and cough. Most infections in primary care are viral infections and self-limiting infections such as otitis media and acute tonsillitis. The given diagnosis may often just reflect the treatment. If otitis is found in addition to upper respiratory infection, the main diagnosis may be otitis media if antibiotics are prescribed and upper respiratory infection if antibiotics are not prescribed. It is not possible from this material to estimate the prescription rate for acute otitis media or tonsillitis.

This observational study is based on a randomised study where every third child got a CRP test before the consultation. This may have increased the total number of CRP tests, and may have resulted in more elevated CRP than would otherwise have been found. It is possible that this may have affected the prescription rate.

The doctors were informed about the study, a fact which may also have affected the outcomes.

Comparison and implications

We found in our study a total prescription rate of 23%, but a higher prescription of amoxicillin (20%) than expected from guidelines.17 This is probably due to the bad taste of PcV mixtures; many will prefer the amoxicillin variants if they have tried it before.19 A recent Norwegian study found a total prescription rate of 26% and nearly the same amount of amoxicillin (26%).20 We found a higher prescription of PcV (67% compared with 42%) and a lower use of macrolides (9% compared with 30%). This reduction in the use of macrolides has been observed in primary care in Norway in the past decade.15 Hopefully, this trend reflects the efforts to decrease the prescription rates of antibiotics and to avoid broad-spectrum antibiotics.

The diagnoses are not comparable from study to study. We found a high prescription rate for otitis media (67%). However, only 42% of those with signs of otitis media got a prescription of antibiotics. This is the same rate as in the mentioned Norwegian study,20 implying that the diagnoses reflect the treatment given. For the diagnoses usually considered to be of bacterial origin as pneumonia, otitis media and tonsillitis, the prescription rate was high even in the presence of low CRP values, but was increasing with increasing CRP values. For diagnoses of unspecific or typical viral origin, there was no prescription with negative CRP (≤20 mg/L) and rising prescription rate at higher CRP values. These results are comparable to data from a Swedish study from 1999 to 2005, but generally prescription rates were higher in this period.21 A more recent study from the UK also showed the same tendency: a strong association between the diagnoses and prescription rates and weaker association between abnormal examination findings and prescription.22

The strongest predictor for prescription in our study was a CRP value >20 mg/L. A value ≤20 mg/L has been found to be useful as a cut-off value for ruling out serious infections.11 Nevertheless, in our study, 13% of those with a CRP value <20 mg/L got a prescription for antibiotics. This may reflect a general lack of confidence in the CRP test, but it is also possible that the clinical condition of the patients in these cases implied a bacterial aetiology, leading the doctor to judge the test result as false negative. The guidelines recommend expectance when CRP is below 50–100 mg/L at day 2 and later.17 Our study shows that the guidelines are often not followed. There may be a potential for further reducing the prescription rate, by using the recommended CRP limits.

The parents' assessments were collected by a questionnaire prior to the consultation. They were just given three choices: no opinion, viral infection and bacterial infection, and were also asked if they thought their child was in need of treatment. There was a strong association between the parents' opinion and the given treatment. This may reflect that the parents know and assess their child well. This may be an important explanation, especially for admission to hospital. However, for prescription, this may also reflect earlier studies that clinicians often prescribe because parents want a prescription.23 Earache was also significantly associated with increased prescription rate. A Dutch study from 2012 found that concerned parents, ill appearance, signs of throat infection and earache were significantly associated with prescription of antibiotics.24 They also found that only a small proportion of the prescriptions were explained by signs and symptoms, and that other non-medical-based considerations may have played a role in the decisions.

Outside Europe, in developing countries the situation is very different in terms of the prescribing rate and what is prescribed. Comparison is difficult due to little regulation of prescribing and self-medication, and there are few publications from primary care.25 From China and India, there are published studies showing prescribing rates of 50–74% in rural areas and a high usage of broad-spectrum antibiotics.26–28 A qualitative study found that poor knowledge of village doctors, patients' demands and financial incentives were important factors affecting the prescription.29 The spread of antimicrobial resistance has led to increased mortality and is especially harmful for small children in areas with a lower standard of sanitation and public health, and a higher prevalence of serious infectious diseases.30 Education, better communication between physicians and parents, diagnostic tests and regulation of the prescription are important factors to influence the development in the right direction. Lessons learnt from efforts to reduce prescription in developed countries may also be used for this purpose.

For the second outcome, referral to hospital, the predictors were different. The main reasons for referral were affected respiration, reflecting the diagnoses most often referred: asthma/bronchiolitis and pneumonia. The respiratory rate and oxygen saturation were measured by the nurses and coincided well with the doctors' opinion of how ill the child was, as well as the parents' assessment of the seriousness. The nurses are the first persons meeting the children at the OOH service and it seems that examination of the child's respiration should be prioritised first, especially when the waiting time to see the doctor is long. All nurses and other staff in the reception of the OOH services should be educated in examination of the child's respiration to be better able to prioritise correctly.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the children, parents, OOH services at Sotra, Askøy, Nordhordland, Os and the Pediatric Emergency Clinic at Haukeland University Hospital who participated in the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: IKR, HS, ABM and SH were involved in the development of the protocol and survey questionnaire. IKR and ABM participated in the data collection. IKR did the analyses and wrote the first draft, and all authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, revision of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The study was funded by Uni Research Health, National Centre for Emergency Primary Healthcare and AMFF, The Norwegian Research Fund for General Practice.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Regional committee for medical and health research ethics (2012/1471/REK Vest). Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Magnus MC, Vestrheim DF, Nystad W et al. Decline in early childhood respiratory tract infections in the Norwegian mother and child cohort study after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2012;31:951–5. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31825d2f76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norwegian Institute of Public Health. http://www.fhi.no (accessed 5 Sep 2016).

- 3.Akre M, Finkelstein M, Erickson M et al. Sensitivity of the Pediatric Early Warning Score to identify patient deterioration. Pediatrics 2010;125:e763–9. 10.1542/peds.2009-0338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brent AJ, Lakhanpaul M, Thompson M et al. Risk score to stratify children with suspected serious bacterial infection: observational cohort study. Arch Dis Child 2011;96:361–7. 10.1136/adc.2010.183111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nijman RG, Vergouwe Y, Thompson M et al. Clinical prediction model to aid emergency doctors managing febrile children at risk of serious bacterial infections: diagnostic study. BMJ 2013;346:f1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verbakel JY, Lemiengre MB, De Burghgraeve T et al. Validating a decision tree for serious infection: diagnostic accuracy in acutely ill children in ambulatory care. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008657 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delaney BC, Hyde CJ, McManus RJ et al. Systematic review of near patient test evaluations in primary care. BMJ 1999;319:824–7. 10.1136/bmj.319.7213.824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rebnord IK, Sandvik H, Hunskaar S. Use of laboratory tests in out-of-hours services in Norway. Scand J Prim Health Care 2012;30:76–80. 10.3109/02813432.2012.684208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rebnord IK, Hunskaar S, Gjesdal S et al. Point-of-care testing with CRP in primary care: a registry-based observational study from Norway. BMC Fam Pract 2015;16:170 10.1186/s12875-015-0385-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falk G, Fahey T. C-reactive protein and community-acquired pneumonia in ambulatory care: systematic review of diagnostic accuracy studies. Fam Pract 2009;26:10–21. 10.1093/fampra/cmn095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van den Bruel A, Thompson MJ, Haj-Hassan T et al. Diagnostic value of laboratory tests in identifying serious infections in febrile children: systematic review. BMJ 2011;342:d3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dagnelie CF, van der Graaf Y, De Melker RA. Do patients with sore throat benefit from penicillin? A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial with penicillin V in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 1996;46:589–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mallory MD, Shay DK, Garrett J et al. Bronchiolitis management preferences and the influence of pulse oximetry and respiratory rate on the decision to admit. Pediatrics 2003;111:e45–51. 10.1542/peds.111.1.e45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Antibiotic resistance in Norway. https://www.fhi.no/en/op/public-health-report-2014/health–disease/antibiotic-resistance-in-norway—p/ (accessed 6 Oct 2016).

- 15.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net). http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/activities/surveillance/EARS-Net/Pages/index.aspx (accessed 6 Jun 2016).

- 16.Handlingsplan mot antibiotikaresistens i helsetjenesten. Oslo: Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.http://helsedirektoratet.no/publikasjoner/nasjonale-faglige-retningslinjer-for-antibiotikabruk-i-primerhelsetjenesten/Publikasjoner/IS-2030_nett_low.pdf (accessed 6 Jun 2016).

- 18.Rebnord IK, Sandvik H, Mjelle AB et al. Out-of-hours antibiotic prescription after screening with C reactive protein: a randomised controlled study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011231 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pottegard A, Hallas J. [Children prefer bottled amoxicillin]. Ugeskr Laeg 2010;172:3468–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fossum GH, Lindbæk M, Gjelstad S et al. Are children carrying the burden of broad-spectrum antibiotics in general practice? Prescription pattern for paediatric outpatients with respiratory tract infections in Norway. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002285 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neumark T, Brudin L, Mölstad S. Use of rapid diagnostic tests and choice of antibiotics in respiratory tract infections in primary healthcare—a 6-y follow-up study. Scand J Infect Dis 2010;42:90–6. 10.3109/00365540903352932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Brien K, Bellis TW, Kelson M et al. Clinical predictors of antibiotic prescribing for acutely ill children in primary care: an observational study. Br J Gen Pract 2015;65:e585–92. 10.3399/bjgp15X686497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lucas PJ, Cabral C, Hay AD et al. A systematic review of parent and clinician views and perceptions that influence prescribing decisions in relation to acute childhood infections in primary care. Scand J Prim Health Care 2015;33:11–20. 10.3109/02813432.2015.1008815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elshout G, Kool M, Van der Wouden JC et al. Antibiotic prescription in febrile children: a cohort study during out-of-hours primary care. J Am Board Fam Med 2012;25:810–18. 10.3122/jabfm.2012.06.110310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu M, Zhao G, Stålsby Lundborg C et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of parents in rural China on the use of antibiotics in children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:112 10.1186/1471-2334-14-112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yin X, Song F, Gong Y et al. A systematic review of antibiotic utilization in China. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013;68:2445–52. 10.1093/jac/dkt223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma M, Damlin A, Pathak A et al. Antibiotic prescribing among pediatric inpatients with potential infections in two private sector hospitals in central India. PLoS One 2015;10:e0142317 10.1371/journal.pone.0142317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma M, Damlin AL, Sharma A et al. Antibiotic prescribing in medical intensive care units—a comparison between two private sector hospitals in Central India. Infect Dis (Lond) 2015;47:302–9. 10.3109/00365548.2014.988747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Z, Zhan X, Zhou H et al. Antibiotic prescribing of village doctors for children under 15 years with upper respiratory tract infections in rural China: a qualitative study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3803 10.1097/MD.0000000000003803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laxminarayan R, Duse A, Wattal C et al. Antibiotic resistance-the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13:1057–98. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70318-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]