Abstract

Introduction

Recognising a tumour predisposition syndrome (TPS) in patients with childhood cancer is of significant clinical relevance, as it affects treatment, prognosis and facilitates genetic counselling. Previous studies revealed that only half of the known TPSs are recognised during standard paediatric cancer care. In current medical practice it is impossible to refer every patient with childhood cancer to a clinical geneticist, due to limited capacity for routine genetic consultation. Therefore, we have developed a screening instrument to identify patients with childhood cancer with a high probability of having a TPS. The aim of this study is to validate the clinical screening instrument for TPS in patients with childhood cancer.

Methods and analysis

This study is a prospective nationwide cohort study including all newly diagnosed patients with childhood cancer in the Netherlands. The screening instrument consists of a checklist, two- and three-dimensional photographic series of the patient. 2 independent clinical geneticists will assess the content of the screening instrument. If a TPS is suspected based on the instrument data and thus further evaluation is indicated, the patient will be invited for full genetic consultation. A negative control group consists of 20% of the patients in whom a TPS is not suspected based on the instrument; they will be randomly invited for full genetic consultation. Primary outcome measurement will be sensitivity of the instrument.

Ethics and dissemination

The Medical Ethical Committee of the Academic Medical Centre stated that the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act does not apply to this study and that official approval of this study by the Committee was not required. The results will be offered for publication in peer-reviewed journals and presented at International Conferences on Oncology and Clinical Genetics. The clinical data gathered in this study will be available for all participating centres.

Trial registration number

NTR5605.

Keywords: 3D photography, Screening Instrument, Morphology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Nationwide study.

Systematically gathering of clinical and phenotypic information and DNA samples of patients with childhood cancer.

Focus on validation of the screening instrument in Dutch medical practice only, feasibility of the screening instrument in other (non-Western World) countries remains unstudied.

No molecular genetic studies were performed, only gathering of samples for molecular studies.

Introduction

It is of significant clinical relevance to recognise a tumour predisposition syndrome (TPS). It may lead to (1) recognition of other signs and symptoms unrelated to cancer, (2) affect treatment, (3) allow suitable cancer surveillance strategies, (4) offer insights into the prognosis of the child, and (5) can facilitate adequate genetic counselling of the child and its family members. Two large cohort studies reported that 7.2–8.5 per cent of patients who develop cancer as a child, have a TPS.1 2 Research in the Netherlands in a large series of children with cancer showed that half of the TPSs were not recognised by the physicians involved in the daily care of the child with cancer.1

It has been proposed that all children with cancer should be examined by a physician familiar with dysmorphology and cancer predisposition, preferably by a clinical geneticist.3 4 However, referring all patients with childhood cancer for genetic evaluation is impossible in current clinical practice due to limited capacity and can be of low priority in acutely ill patients.

We propose to implement an easy-to-use screening instrument that can be used in all patients with childhood cancer to facilitate detection of patients at risk for having a TPS. Using the instrument, the clinical geneticist can remotely review the patient for suspicion for a TPS and thus determine the need for referral for a full clinical genetic evaluation. The screening instrument should guarantee that the presence of a TPS is adequately evaluated in each child with cancer. Such a screening instrument should be easy to execute by a research nurse, genetic counsellor or treating physician. The screening instrument should be based on the morphological abnormalities (manifestations) of known TPSs, as these manifestations have been shown to indicate cancer susceptibility.1 3 5 Part of the manifestations of TPSs will be visible on two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) photographs. This will support remote evaluation of detailed morphological characteristics of the patient by a clinical geneticist, and enable discussion with colleagues if desired. However, not all manifestations will be visible in these photographs. Therefore, we have recently identified the most important and sensitive manifestations of known TPSs that are not detectable on such photographs. This list of 47 specific manifestations was composed following a two-round Delphi process with eight international content-specific experts.6 Subsequently, we have developed the screening instrument, consisting of the 2D and 3D photographic series complemented by a childhood cancer syndrome checklist (CCSC, see online supplementary appendix 1) listing the selected manifestations not visible on this set of photographs completed with patient characteristics and family history.

In 2016, Jongmans et al7 developed a selection tool based on the literature and expert opinion/empirical data, designed to support paediatric oncologists in their choice to refer a patient for clinical consultation or not. Since the concept and methodology of the selection tool described by Jongmans et al and our screening instrument differ markedly, parallel validation is not possible as it would interfere with the current study methodology.

Study aim

The primary aim of the Validation of a clinical screening instrument for tumour predisposition syndromes in patients with childhood cancer (TuPS) study is to assess the clinical validity of the screening instrument in identifying patients with childhood cancer at risk for a TPS from a non-selected prospective cohort of patients with childhood cancer. We hypothesise that the screening instrument will be equivalent to or better than the current practice in recognising patients with a TPS and we assume high sensitivity (94%), and therefore being generally accepted as clinically relevant.

The secondary aim of the TuPS study is to identify (patterns of) morphological abnormalities in a patient with childhood cancer with predictive value by using 3D facial analysis to improve the screening instrument. Improvement of diagnostic value due to implementation of specific morphological abnormalities will be expressed in terms of effect on sensitivity of the screening instrument. We hypothesise that we will find significant differences in facial phenotypes unrelated to therapy between patients with childhood cancer and their healthy peers.

Methods and analysis

Study design

TuPS is a prospective, observational, nationwide, multicentre patient cohort study. Eligible consecutive patients with childhood cancer will be included after informed consent has been obtained from their parents (and themselves if 12 years or older), according to the current Dutch ethical regulations.

Study flow

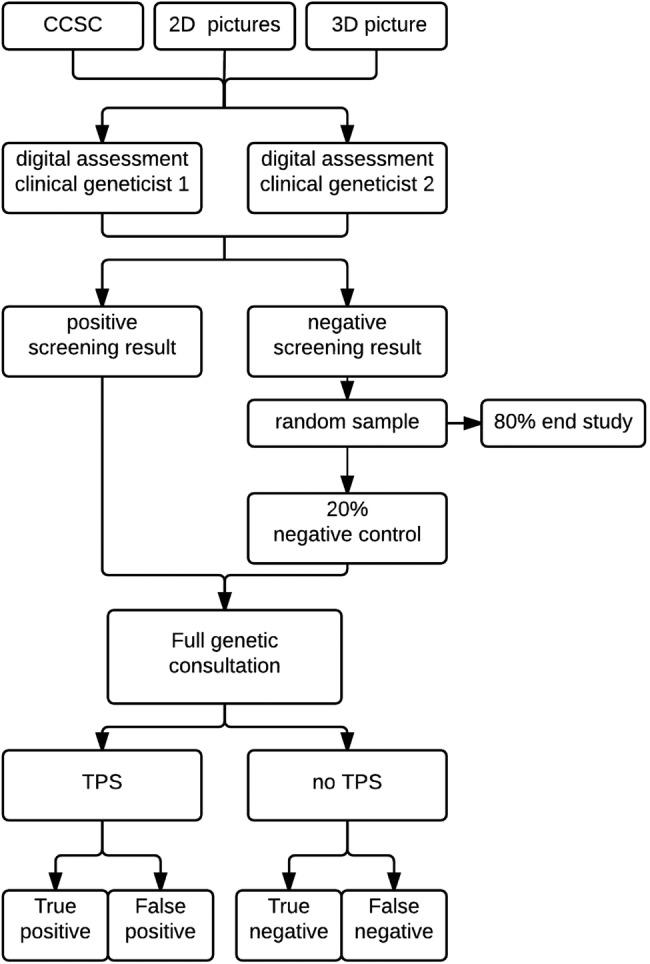

The study flow is depicted in figure 1. After written consent, the patient will be seen by the local genetic counsellor or research nurse who will give the patient a coded study number. The study numbers are centrally supplied by the study coordinator. The genetic counsellor/research nurse will complete the CCSC. In addition, 2D and 3D digital photographs will be taken by the local medical photographer. The data gathered (CCSC and photographic series) will be uploaded in a central database and presented electronically to two independent clinical geneticists from centres different from the patient’s centre. The two clinical geneticists will assess the content of the screening instrument, by answering a short questionnaire (table 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow. 2D, two-dimensional; 3D, three-dimensional; CCSC, childhood cancer syndrome checklist; TPS, tumour predisposition syndrome.

Table 1.

Questionnaire for decision of clinical geneticist using screening instrument

| 1. | Is there for this patient any reason for referral to a clinical geneticist for further examination into the suspicion of the presence of a TPS? |

| If no: end questionnaire | |

| 2. | Based on what is your decision made? (Multiple answers possible) □ The type of malignancy □ Medical history of the patient □ Family history □ Morphological abnormality as depicted on the childhood cancer checklist □ Morphology 2D pictures □ Morphology 3D picture |

| 3. | Would you refer the patient if you did not have the access to the 2D and 3D pictures? |

|

If no: ○ My referral was mainly based on the 2D pictures ○ My referral was mainly based on the 3D picture ○ My referral was mainly based on both the 2D and 3D pictures |

2D, two-dimensional; 3D, three-dimensional; TPS, tumour predisposition syndrome.

Patients in whom a TPS is suspected by one or both clinical geneticists (ie, a positive screening result) will be referred for full genetic consultation in the patient's own treatment centre (‘gold standard’). Note that the local clinical geneticist who will perform the full genetic consultation will be different from the independent clinical geneticists performing the digital assessment of the same patient using the screening instrument. Patients in whom a TPS is not suspected by both clinical geneticists (ie, a negative screening result) will randomly be invited to follow full genetic consultation as well. This randomisation will be carried out by the study coordinator in 1:5 ratio, using the online randomisation database ALEA (ALEA software, TenALEA consortium, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The evaluation of any child with cancer is part of standard patient care, and the referral of these children is therefore also part of normal care and costs are covered by the health insurances. The local clinical geneticist, referred patients and their parents are blinded to the result of the digital assessment of the screening instrument.

Molecular confirmation of suggested clinical diagnoses is not part of the study design. Study participants in whom a clinical diagnosis is suspected will be referred for routine patient care studies to the clinical geneticist. In the Netherlands a clinical diagnosis is invariably confirmed by molecular testing if this is available for the entity involved.

The results of the full genetic consultation will be allocated to one of three categories: confirmed TPS; no TPS; and a private syndrome, defined as strong suspicion of a TPS based on medical history, physical signs and symptoms but not fitting a recognisable pattern of a known TPS. We will classify a confirmed TPS on clinical grounds, which should be confirmed by an appropriate metabolic, cytogenetic, or molecular test whenever possible. The trial will be reported according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines as far as applicable.

Study setting

The study is to be carried out in all six paediatric oncology centres and their allied clinical genetic departments, in the Netherlands: Emma Children's Hospital/Academic Medical Centre Amsterdam, VU University Medical Centre Amsterdam, Sophia Children's Hospital/Erasmus Medical Centre Rotterdam, Princess Máxima Centre for Paediatric Oncology/University Medical Centre Utrecht, Beatrix Children's Hospital/University Medical Centre Groningen, Radboud University Medical Centre Nijmegen. The recruitment period will be 2 years, starting from January 2016.

Screening instrument

Childhood cancer syndrome checklist

The CCSC consists of patient characteristics (history, tumour type and development), family history and 47 selected specific physical manifestations which may not be detectable on 2D and 3D photographs (see online supplementary appendix 1).6

bmjopen-2016-013237supp_appendix1.pdf (166.4KB, pdf)

Generally, the CCSC will be completed by a genetic counsellor or a research nurse. If this is not possible, any person with sufficient medical background, but without explicit knowledge on TPSs, may do so. The genetic counsellor/research nurse will receive a booklet that has been developed specifically for this study, showing definitions for the 47 specific manifestations (not visible on photographs, selected using Delphi as described in the Introduction section) to be aware of during physical examination.

2D and 3D photographic series

In this study, only the patient will be photographed. The photographic series consists of 2D photograph of the face (front portrait and profile), hands, feet and skin and one 3D photograph of the face. The photographs allow for repeated measurements, close inspection with minimal intrusion and without requiring prolonged cooperation of the patient. Using 3D models, the average shape of a collection of faces can be computed, quantitative shape comparisons of face surfaces can be performed and face shape of a patient can be normalised with respect to ethnicity, age and sex matched mean.8 The photographs will be taken by the local (trained) medical photographer, using their own 2D camera and a centrally provided 3D camera: the VECTRA M3 Imaging System, manufactured by Canfield Scientific (http://www.canfieldsci.com).

Decision support scheme

Two independent clinical geneticists will be invited to assess the content of the screening instrument (CCSC and photographic series) electronically, by means of the decision support scheme. The decision support scheme is a preassembled document, approved by all participating clinical geneticists of the six centres (see online supplementary appendix 2). It states when a patient should be referred to a clinical geneticist for complete genetic consultation. It consists of four parts; questions on malignancy, medical history, family history and morphological examination. The clinical geneticists are blinded to each other's assessment.

bmjopen-2016-013237supp_appendix2.pdf (143.4KB, pdf)

Malignancy: A comprehensive search in PubMed was carried out. The purpose of this search was to provide an overview of the literature on the likelihood of the presence of a TPS per type of malignancy in children. Subsequently, the results for malignancy-driven referral for genetic evaluation for TPSs in childhood cancer have been discussed during a Dutch nationwide meeting until consensus was reached. These results will be offered for publication (Postema et al, in preparation).

Medical history: Various aspects of the medical history of the patient can lead to referral to a clinical geneticist. According to expert opinion and the consensus meeting these aspects include: previous primary cancers, learning and developmental problems, growth problems or specific other medical problems in the context of a TPS, such as immunodeficiency or organ malformations/dysfunction.

Family history: According to expert opinion and the consensus meeting, referral to a clinical geneticist should be considered when cancer occurs in family members up to the third degree.

Morphological examination: Morphological abnormalities may be noticed using the CCSC as described above, or on the 2D and 3D photographic series.

Patients

Criteria

All patients with childhood cancer in the Netherlands seen by a paediatric oncologist during the study period will be screened for eligibility. The inclusion criteria for enrolment of patients are: (1) age 0–18 years; and (2) a newly diagnosed malignancy. Patients are excluded if they have already been diagnosed with a syndrome known to be associated with the current observed malignancy.

Sample size

This study is the first to assess the clinical value of a newly developed screening instrument in a national childhood cancer population that includes all types of malignancies. Therefore, the sample size calculation is based on 7.2% as the minimal prevalence of a TPS in patients with childhood cancer, based on the results of the study of Merks et al.1 This might be an underestimate because the majority of patients included in this published study were survivors; the incidence of TPSs in survivors might be low due to the negative influence of some TPSs on survival.1 Next to that, TPSs without malformations, such as the Li-Fraumeni syndrome have not been identified in this clinical morphological examination study.

The incidence of childhood cancer, based on historical annual reports of the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group (DCOG) was estimated as 550 newly diagnosed patients per year.

For a screening instrument to be clinically relevant, we assumed a sensitivity of 94% or higher to be acceptable. Since specificity is unknown, we used an assumed specificity of 50% in our power calculations. For power calculations, we followed the methodology described by Jones et al.9

Using these assumptions associated with the study design (prevalence 7.2%, sensitivity 94% and specificity 50%), we expect to find 532 patients with a positive screening result in a theoretical cohort of 1000 evaluable individuals (table 2). We expect to find 468 individuals with a negative screening result. From this group, 20% are evaluated to determine the number of false negatives. Under these conditions, we are allowed to find a maximum of one false-negative individual in the 20% sample. If this holds true we can conclude that 98.9% (CI 94.2 to 99.8) of negatively screened individuals are indeed true negatives. In this scenario, we would need a group of 626 patients (532 patients with a positive screening and 94 patients selected for random sample ie, 20% of 468 patients with a negative screening result) who are seen by a clinical geneticist for a standard genetic consultation. Based on prior experience, we expect a 90% participation rate and an extremely low frequency of drop outs (including study withdrawal). Owing to this expected low frequency of drop outs, these are not included in the calculations.

Table 2.

2×2 Table sample size calculations

| TPS+ | TPS− | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening+ | 68 | 464 | 532 |

| Screening− | 4 | 464 | 468 |

| 72 | 928 | 1000 |

TPS, tumour predisposition syndrome.

Withdrawal of individual patients

Patients can withdraw from the study at any time, without giving reasons. Data and samples already registered can be analysed unless the patient and/or parent(s) decide otherwise.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Objective 1: validation of the screening instrument

The primary outcome measurement for aim 1 (validation of the screening instrument) is sensitivity of the screening instrument. The screening instrument should have a high sensitivity, as we do not want to miss patients with a potential TPS. True-positive patients are defined as patients with a positive screening result and in whom presence of a TPS or the presence of a private syndrome was confirmed in full clinical genetic consultation. False-negative patients are defined as patients with a negative screening result, in whom presence of a TPS or the presence of a private syndrome was confirmed in full clinical genetic consultation.

For the analysis of specificity, positive and negative predictive value, we define false positive patients as patients with positive screening results in whom no TPS could be confirmed in full clinical genetic consultation and true negative cases as patients with a negative screening result, randomised in the 20% control group, in whom no TPS could be confirmed in full clinical genetic consultation.

Interobserver variability will be assessed. Also, individual attribution of the CCSC and (2D and 3D) photographic series to the conclusion of the assessment a clinical geneticist will be a secondary outcome measurement. In addition to that, we will study a subset of patients in a blinded study based on either morphology on the 3D photograph or results of the complete screening instrument (also including 2D photographs and CCSC).

A final secondary outcome measurement is the difference in healthcare-related costs of the diagnostic process using the instrument compared with current standard clinical genetic care. All costs in total, and costs divided according to the various parts of the screening instrument, will be calculated.

Objective 2: identifying morphological abnormalities

Shape-related differences in facial morphology (determined with 3D photograph) between patients with childhood cancer and their healthy peers will be expressed in colour-coded heat maps and signature graphs. Anthropometric distances using landmark calculations will be used to further illustrate observed differences as found in shape analyses.

Clinical data collection

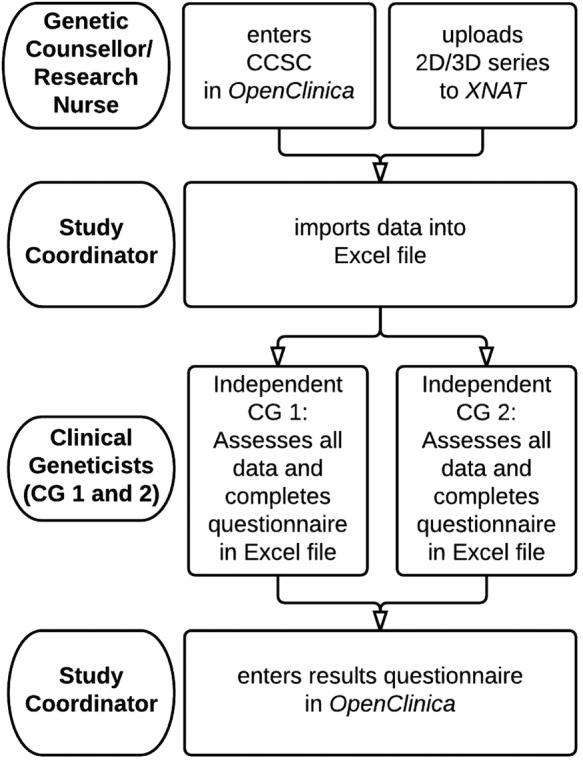

Data on patient characteristics are collected during the first meeting with the genetic counsellor/research nurse, including month and year of birth; sex; ethnic background; oncological diagnosis and treatment. Furthermore, data are collected on the clinical history of the patient, including the pregnancy; development and family history. Finally, data on physical examination are collected, including anthropometric data (see online supplementary appendix 1). For a flow diagram of the clinical data collection see figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of clinical data collection. 2D, two-dimensional; 3D, three-dimensional; CCSC, childhood cancer syndrome checklist.

The genetic counsellor/research nurse will enter the CCSC outcomes to the corresponding electronic case report form (eCRF) in the online database OpenClinica, V.3.6,10 and upload the photographic series to the online database XNAT, V.1.6.4.11 The two clinical geneticists will receive an Excel file, with the imported data from OpenClinica, a protected link to the XNAT website, and a short questionnaire. After the questionnaire is completed, the clinical geneticist will return the Excel file to the study coordinator, who will fill in the corresponding eCRF in OpenClinica. To ensure complete independence between the two clinical geneticists, it is not possible for the clinical geneticists to enter their result directly in OpenClinica, where they would be able to see each other's assessment.

After the full genetic consultation, the result of the consultation will be sent to the study coordinator, who will enter the result in the corresponding eCRF in OpenClinica. The data of the results of the assessment of the two clinical geneticist and the coded results of the routine genetic consultation will be visually checked by a second investigator, in order to ensure data integrity.

Data analysis and general statistic considerations

Clinical study data

Descriptive statistics will be performed (cross-tabulation, frequencies for positive and negative screening results). Continuous normally distributed variables will be expressed by their mean and SD, or if not normally distributed, as medians and their IQRs. Categorical variables will be expressed as counts (n) and percentages (%). From these data, the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value of the screening instrument will be deduced. For the interobserver variability we will use a Fleiss’ κ score. For these calculations, study data will be exported to IBM SPSS Statistics V.22.

3D analyses

To illustrate the differences in facial phenotype of patients with childhood cancer in comparison with healthy controls,12 both shape-related and anthropometric analyses will be performed. To determine any difference of importance in morphology between patients and controls, patient's face shape data will be normalised to sex-matched, age-matched and ethnicity-matched controls, and expressed in colour-coded heat maps visualising regional differences. Positive predictive value of morphological abnormalities will be calculated using univariate analysis. For morphological abnormalities with a high-positive predictive value, effect on the sensitivity of the screening instrument will be modelled using multivariate analysis. The control groups for Caucasian children, matched for sex and age are already available for the 3D analyses. For other ethnic groups, the control groups are at present limited but are rapidly expanding, and likely sufficient numbers will be available at the end of the study period.12

Furthermore, anthropometric distances using landmark calculations will be used to further illustrate observed differences as found in shape analyses, as they are demonstrated to be reliable and reproducible.13 14 Differences in anthropometric distances between patients and controls will be calculated using Student's t-tests, in presence of a normal distribution.

In addition, by comparing original face surfaces to their reflected form, we can study asymmetry and investigate if there is greater facial asymmetry in the patient group compared with controls. In the 3D analyses, we will make use of surface shape differences not detectable by simple linear or angular characteristics as might be used in analyses based on measures captured manually or derived from landmarks annotating 2D photographic images. That way we will use 3D morphometric analysis in this heterogeneous patient group to further delineate face shape differences that are too subtle or geometrically complex to identify or quantify objectively with conventional clinical and anthropometric approaches. The methodology of the 3D analyses is described in detail elsewhere.8

Finally, one can demonstrate in so called ‘signature’ graphs the similarity between patients in terms of deviation from the average for specific regions of the face or when appreciating the facial morphology from a specific axis. This way one can use 3D analysis to determine new patterns of morphological abnormalities that cannot be distinguished by the naked eye. These applications of 3D analysis are further illustrated by Hammond and Suttie8 and Hopman et al.15

Biobank

In addition to the validation of the screening instrument, we have created a biobank in cooperation with DCOG. We will ask all recruited patients to provide a blood sample during one of the regular blood tests undertaken for patient care. DNA will be extracted, and stored in a central biobank at DCOG. The DNA is intended for future scientific research into the aetiology of childhood cancer. All data will be coded and stored for 15 years.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics

The Medical Ethical Committee of the Academic Medical Centre (Amsterdam, the Netherlands) stated that the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO) does not apply to the TuPS study and that official approval of this study by the Committee was not required (W14_251 #14.17.0303 10-09-2015). The Biobanking Committee of the Academic Medical Centre approved the biobank procedure described above (2015_133#A2015103 02-11-2015).

Consent

Patients newly diagnosed with a childhood malignancy and their parents will be informed by their paediatric oncologist, who will supply them with written information on all relevant aspects of the TuPS study including separate information on participation in the biobank procedure. When the patient is younger than 12 years, correspondence is directed to the parent(s) or guardian(s). When the patient is between 12 and 18 years, correspondence is directed to both the patients and their parent(s) or guardian(s). Written informed consent will be given by patient and parents when 12 years or older, by parents alone when the patient is younger than 12 years.

The informed consent forms for participation in the TuPS study and the biobanking part are separated.

Privacy

The online databases OpenClinica, XNAT and ALEA are only accessible with assigned log in credentials.

Personal data of participating patients will be strictly separated from the study data. The genetic counsellor/research nurse of each participating site has the encryption key for the coded patient number and has access to the personal data of the enrolled patients in their own centre.

The encryption key is only accessible for the principal investigator and the executive researcher.

Dissemination

After finalisation of the project, all information gathered in this study, with the exception of the photographs, will be stored at DCOG. The 2D and 3D photographic series will be stored at the AMC. The coded data is accessible for all the participating centres. The DCOG research committee complemented by the chair of the DCOG task force on childhood oncogenetics will assess additional requests to use the information gathered by the study.

The encryption key from the six centres will be combined and stored at an independent location, supervised by the principal investigator.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Members of the TuPS study group: Cora M Aalfs (Department of Clinical Genetics, Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), Jakob K Anninga (Department of Paediatric Oncology, Amalia Children's Hospital, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands), Lieke PV Berger (Department of Genetics, University Medical Centre Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands), Fonnet E Bleeker (Department of Clinical Genetics, Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), Eveline SJM de Bont (Department of Paediatric Oncology, Beatrix Children's Hospital/University Medical Centre Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands), Corianne AJM de Borgie (Clinical Research Unit, Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), Charlotte J Dommering (Department of Clinical Genetics, VU University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), Natasha KA van Eijkelenburg (Princess Máxima Centre for paediatric oncology/University Medical Centre Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands), Peter Hammond (Nuffield Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK), Raoul C Hennekam (Department of Paediatrics, Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), Marry M van den Heuvel-Eibrink (Princess Máxima Centre for Paediatric Oncology/University Medical Centre Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands), Saskia MJ Hopman (Department of Paediatric Oncology, Emma Children's Hospital, Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Department of Genetics, University Medical Centre Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands), Marjolijn CJ Jongmans (Department of Genetics, University Medical Centre Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands; Department of Human Genetics, Radboud University Medical Centre Nijmegen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands), Wijnanda A Kors (Department of Paediatric Oncology, VU University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), Tom GW Letteboer (Department of Genetics, University Medical Centre Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands), Jan LCM Loeffen (Department of Paediatric Oncology, Sophia Children's Hospital, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam, The Netherlands), Johannes HM Merks 744: (Department of Paediatric Oncology, Emma Children's Hospital, Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), Maran JW Olderode-Berends (Department of Genetics, University Medical Centre Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands), Floor AM Postema (Department of Paediatric Oncology, Emma Children's Hospital, Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), Anja Wagner (Department of Clinical Genetics, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam, The Netherlands).

Contributors: FAMP contributed to the study concept and design, participation in consensus meeting, design of data collection tools, and drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. SMJH contributed to the study conception and design, participation in consensus meeting, and drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. CAJMdB contributed to the study concept and design, and drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. PH contributed to the study concept and design, and to the critical revision of the manuscript. JHMM contributed to the study concept and design, participation in consensus meeting, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript, and overseeing the total study. RCH contributed to the study concept and design, drafting and critical revision of manuscript, and overseeing the total study.

Funding: This work was supported by the foundation Children Cancer-free (Kinderen Kankervrij (KiKa)) (grant number 143).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Medical Ethical Committee of the Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Merks JH, Caron HN, Hennekam RC. High incidence of malformation syndromes in a series of 1,073 children with cancer. Am J Med Genet A 2005;134A:132–43. 10.1002/ajmg.a.30603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang J, Walsh MF, Wu G et al. . Germline mutations in predisposition genes in pediatric cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2336–46. 10.1056/NEJMoa1508054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Méhes K. Malformations in children with cancer. Am J Med Genet A 2006;140:932 10.1002/ajmg.a.31183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orellana C. Malformation syndromes during cancer in childhood. Lancet Oncol 2005;6:198 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70076-015830446 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merks JH, Ozgen HM, Koster J et al. . Prevalence and patterns of morphological abnormalities in patients with childhood cancer. JAMA 2008;299:61–9. 10.1001/jama.2007.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hopman SM, Merks JH, de Borgie CA et al. . The development of a clinical screening instrument for tumour predisposition syndromes in childhood cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:3247–54. 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jongmans MC, Loeffen JL, Waanders E et al. . Recognition of genetic predisposition in pediatric cancer patients: an easy-to-use selection tool. Eur J Med Genet 2016;59:116–25. 10.1016/j.ejmg.2016.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammond P, Suttie M. Large-scale objective phenotyping of 3D facial morphology. Hum Mutat 2012;33:817–25. 10.1002/humu.22054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones SR, Carley S, Harrison M. An introduction to power and sample size estimation. Emerg Med J 2003;20:453–8. 10.1136/emj.20.5.453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Visser G, Smeets E.2011. OpenClinica's (low cost) eCRF, an investigator-initiated study's showcase. Secondary OpenClinica's (low cost) eCRF, an investigator-initiated study's showcase. http://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/print/211800?page=full.

- 11.Marcus DS, Olsen TR, Ramaratnam M et al. . The Extensible Neuroimaging Archive Toolkit: an informatics platform for managing, exploring, and sharing neuroimaging data. Neuroinformatics 2007;5:11–34. 10.1385/NI:5:1:11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopman SM, Merks JH, Suttie M et al. . Face shape differs in phylogenetically related populations. Eur J Hum Genet 2014;22:1268–71. 10.1038/ejhg.2013.289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aldridge K, Boyadjiev SA, Capone GT et al. . Precision and error of three-dimensional phenotypic measures acquired from 3dMD photogrammetric images. Am J Med Genet A 2005;138A:247–53. 10.1002/ajmg.a.30959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gwilliam JR, Cunningham SJ, Hutton T. Reproducibility of soft tissue landmarks on three-dimensional facial scans. Eur J Orthod 2006;28:408–15. 10.1093/ejo/cjl024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hopman SM, Merks JH, Suttie M et al. . 3D morphometry aids facial analysis of individuals with a childhood cancer. Am J Med Genet A 2016;170:2905–15. 10.1002/ajmg.a.37850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013237supp_appendix1.pdf (166.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013237supp_appendix2.pdf (143.4KB, pdf)