Abstract

Objectives

Isolated minor rib fractures (IMRFs) after blunt chest traumas are commonly observed in emergency departments. However, the relationship between IMRFs and subsequent pneumonia remains controversial. This nationwide cohort study investigated the association between IMRFs and the risk of pneumonia in patients with blunt chest traumas.

Design

Nationwide population-based cohort study.

Setting

Patients with IMRFs were identified between 2010 and 2011 from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database.

Participants

Non-traumatic patients were matched through 1:8 propensity-score matching according to age, sex, and comorbidities (namely diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)) with the comparison cohort. We estimated the adjusted HRs (aHRs) by using the Cox proportional hazard model. A total of 709 patients with IMRFs and 5672 non-traumatic patients were included.

Main outcome measure

The primary end point was the occurrence of pneumonia within 30 days.

Results

The incidence of pneumonia following IMRFs was 1.6% (11/709). The aHR for the risk of pneumonia after IMRFs was 8.94 (95% CI=3.79 to 21.09, p<0.001). Furthermore, old age (≥65 years; aHR=5.60, 95% CI 1.97 to 15.89, p<0.001) and COPD (aHR=5.41, 95% CI 1.02 to 3.59, p<0.001) were risk factors for pneumonia following IMRFs. In the IMRF group, presence of single or two isolated rib fractures was associated with an increased risk of pneumonia with aHRs of 3.97 (95% CI 1.09 to 14.44, p<0.001) and 17.13 (95% CI 6.66 to 44.04, p<0.001), respectively.

Conclusions

Although the incidence of pneumonia following IMRFs is low, patients with two isolated rib fractures were particularly susceptible to pneumonia. Physicians should focus on this complication, particularly in elderly patients and those with COPD.

Keywords: Isolated minor rib fractures, blunt chest trauma, pneumonia, nationwide cohort study

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strength of this cohort study was the use of the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2010, which includes the nationwide data of 1 million insureds randomly selected from the 2010 Registry of Beneficiaries. Taiwan's National Health Insurance system, established in 1995, covers the medical expenses of ∼98% of the Taiwanese population, providing accurate data of medical conditions in Taiwan.

We obtained the number of rib fractures experienced by the patients from the data sets; however, information on the type of rib fractures was not obtained. Fractures of the first 3 ribs indicated a high-energy injury that may lead to increased complications.

The National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) does not provide detailed clinical parameters, such as the trauma mechanisms, injury severity score, abbreviated injury scale and laboratory data of the patients. Injury severity was one of the factors contributing to the risk of pneumonia in patients with multiple rib fractures.

Introduction

Pneumonia is an inflammatory process of the alveolar regions of the lung, which typically occurs because of microbial infections.1 2 The incidence of pneumonia ranged from 1.5 to 14 cases per 1000 person-years and was the second major cause of deaths and years of life lost in 2013.3–5 Microorganisms that colonise the oropharynx and nasopharynx, including bacteria, virus, fungi and protozoa, are a common aetiology of pneumonia. Aspiration of the contaminated secretions causing pneumonia is common in trauma populations.6

Chest traumas account for ∼796 000 emergency department (ED) visits annually in the USA.7 In Taiwan, chest traumas caused 18 856 hospitalisations during 2002–2004.8 Rib fractures are common in 7%–40% of all trauma cases, and 10% of the patients with traumatic rib fractures require hospitalisation.9 Furthermore, delayed pneumonia complications were common after multiple rib fractures.10 However, a low risk of delayed pneumonia was reported in patients with minor thoracic injuries.11

Minor thoracic injury, which is defined by the presence of chest abrasion, chest contusion, or single or two isolated minor rib fractures (IMRFs), accounts for up to 42% of ED visits for blunt chest traumas.12 13 Most patients were directly discharged from ED after primary management. However, complications such as delayed pneumothorax, haemothorax, pneumonia and considerable functional limitations have been reported.11 14–16 Among all types of minor thoracic injuries, IMRFs after chest traumas are commonly observed in EDs; however, different ED settings have different disposition practices.17 IMRFs can cause considerable pain, impairing the coughing function and secretion clearance and leading to atelectasis and subsequent pneumonia.18 However, studies exploring the relationship between IMRFs and subsequent pneumonia have been limited to small sample sizes.11 17 19 20 This relationship is clinically relevant because delayed pneumonia after rib fractures has been strongly associated with mortality.21

Materials and methods

Data sources

A retrospective cohort population-based study was conducted using the registration and claims data sets from 2009 to 2011 obtained from the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2010 (LHID2010), which is a subset of the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) managed by the Taiwan National Health Research Institutes. Taiwan's National Health Insurance (NHI) system, established in 1995, covers the medical expenses of ∼98% of Taiwan's residents (23 million); thus, it is one of the world's largest population-based data sets. The LHID2010 has a longitudinal design, containing all ambulatory and inpatient claims data, including disease diagnosis codes, drug prescriptions, diagnostic examinations and interventions, of 1 million beneficiaries (from 23 million) randomly sampled from the 2010 Registry of Beneficiaries of the NHIRD. In this study, the disease diagnosis codes were derived from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). The disease diagnosis coding is highly reliable because all insurance claims are scrutinised by medical reimbursement specialists and peer reviewers.

Study sample size and settings

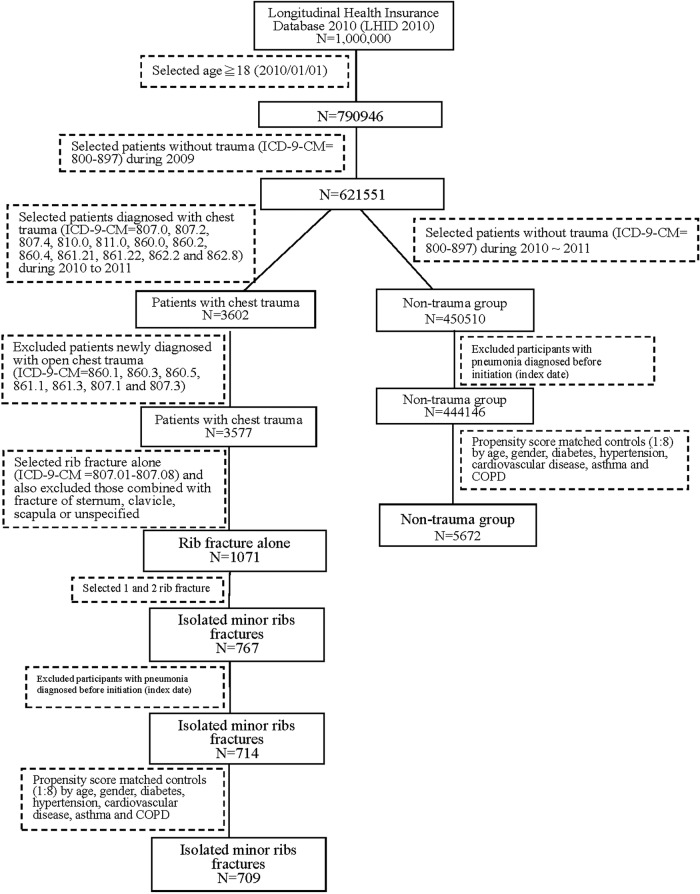

All patients aged ≥18 years with blunt chest traumas between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2011 were identified. Chest trauma was defined according to ICD-9-CM 807.0, 807.2, 807.4, 810.0, 811.0, 860.0, 860.2, 860.4, 861.21, 861.22, 862.2 and 862.8. First, we excluded patients aged <18 years and those with a history of any traumas in the past 1 year (ICD-9-CM 800–897). Subsequently, we excluded patients diagnosed as having open chest trauma, traumatic pneumothorax and haemothorax (ICD-9-CM 860.1, 860.3, 860.5, 861.1, 861.3, 807.1 and 807.3) during the study period because these types of pulmonary injuries can lead to subsequent pneumonia. Furthermore, patients with a history of pneumonia before chest traumas were excluded. IMRFs are defined as single or two rib fractures (ICD-9-CM 807.01 and 807.02) without other associated injuries.11 In addition, data on diagnostic tests, such as chest X-ray (XR; order codes: 32001C, 32002C and 32003C) and CT; order codes: 33066B, 33070B, 33071B, and 33072B), were also obtained. Logistic regression analysis was conducted after propensity score matching for directly calculating the probability values of each pair of cases. The similarities between the probability values of the IMRF and control groups were determined. The optimal ratio from the analysis of variable multiple pairing was 1:8. Therefore, a propensity score matching (1:8) was performed for the control group according to age, sex, diabetes mellitus (ICD-9-CM 250), hypertension (ICD-9-CM 401–405), cardiovascular disease (ICD-9-CM 410–414), asthma (ICD-9-CM 493) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; ICD-9-CM 491, 492, 494 and 496). For determining the occurrence of any type of pneumonia, our study end points were pneumonia diagnosis (ICD-9-CM 481, 482.xx, 483.xx, 485 and 486), withdrawal from the NHI programme or 31 December 2011, whichever occurred first within 30 days of follow-up. Figure 1 illustrates our study framework. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Chung Shan Medical University Hospital (CS2–15061). All personal data in the secondary files were de-identified before analysis; therefore, the review board waived the requirement to obtain written informed consent from the patients.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for selecting patients with isolated minor rib fractures. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages and were compared using the χ2 test where appropriate. Continuous data are presented as the mean±SD and were compared using the independent t test. The Cox proportional hazard model was used for estimating the adjusted HR (aHR) for pneumonia. In addition, we adjusted for the potential confounding factors increasing the risk of pneumonia, namely age, sex, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, asthma and COPD. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS V.18.0 (SPSS , Chicago, Illinois, USA). p<0.05 indicated statistical significance. The occurrence of pneumonia was assessed through Kaplan-Meier analysis, and significance was evaluated on the basis of the log-rank test.

Results

After excluding patients aged <18 years and patients who experienced traumas in the past 1 year, only 3602 patients with chest traumas were included. After matching, a total of 709 patients with IMRFs and 5672 non-traumatic patients were selected for final analysis (figure 1). Furthermore, 207 patients (29.2%) diagnosed as having IMRFs were admitted to hospitals. Table 1 presents the baseline demographics and comorbidities of the IMRF and control groups. After matching, the baseline demographics and comorbidities of the two groups did not vary significantly.

Table 1.

Demographic data of study population

| Unmatched |

Matched |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMRF N=714 |

Non-traumatic patients N=444 146 |

IMRF N=709 |

Non-traumatic patients N=5672 |

|||||||

| n | Per cent | n | Per cent | n | Per cent | p Value | n | Per cent | p Value | |

| Age on index date (years) | <0.001** | 0.258 | ||||||||

| 18–39 | 131 | 18.3 | 209 958 | 47.3 | 131 | 18.5 | 942 | 16.6 | ||

| 40–64 | 377 | 52.8 | 186 801 | 42.1 | 377 | 53.2 | 2977 | 52.5 | ||

| ≧65 | 206 | 28.9 | 47 387 | 10.7 | 201 | 28.3 | 1753 | 30.9 | ||

| Mean±SD | 55.7±16.1 | 43.2±16.0 | <0.001** | 55.4±15.9 | 56.1±15.6 | 0.316 | ||||

| Age on index date (years) | <0.001** | 0.164 | ||||||||

| <65 | 508 | 71.1 | 396 759 | 89.3 | 508 | 71.7 | 3919 | 69.1 | ||

| ≧65 | 206 | 28.9 | 47 387 | 10.7 | 201 | 28.3 | 1753 | 30.9 | ||

| Mean±SD | 55.7±16.1 | 43.2±16.0 | <0.001** | 55.4±15.9 | 56.1±15.6 | 0.316 | ||||

| Gender | <0.001** | 0.711 | ||||||||

| Female | 279 | 39.1 | 230 131 | 51.8 | 277 | 39.1 | 2257 | 39.8 | ||

| Male | 435 | 60.9 | 214 015 | 48.2 | 432 | 60.9 | 3415 | 60.2 | ||

| Diabetes | 105 | 14.7 | 26 566 | 6.0 | <0.001** | 104 | 14.7 | 822 | 14.5 | 0.900 |

| Hypertension | 198 | 27.7 | 57 382 | 12.9 | <0.001** | 194 | 27.4 | 1590 | 28.0 | 0.708 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 62 | 8.7 | 15 161 | 3.4 | <0.001** | 58 | 8.2 | 462 | 8.1 | 0.974 |

| Asthma | 31 | 4.3 | 632 | 0.1 | <0.001** | 30 | 4.2 | 240 | 4.2 | 1 |

| COPD | 45 | 6.3 | 9125 | 2.1 | <0.001** | 43 | 6.1 | 322 | 5.7 | 0.675 |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IMRF, isolated minor ribs fractures.

The incidence of pneumonia after IMRFs was 1.6% (11/709). More than 99% and 9% of the patients underwent only chest XR examination and both chest XR and CT examinations, respectively. The patients with IMRFs were at an increased risk of subsequent pneumonia within 30 days. The aHR for pneumonia was 8.94 (95% CI 3.79 to 21.09, p<0.001) after adjustment for age, sex and comorbidities. Moreover, old age (≥65 years; aHR=5.60, 95% CI 1.97 to 15.89, p<0.001) and COPD (aHR=5.41, 95% CI 1.02 to 3.59, p<0.001) were risk factors for pneumonia (table 2). Table 3 demonstrates the risk stratification of pneumonia in the IMRF group; 476 and 233 patients had single and two isolated rib fractures, respectively. The aHRs of pneumonia in isolated single or two rib fractures were 3.97 (95% CI 1.09 to 14.44, p<0.001) and 17.13 (95% CI 6.66 to 44.04, p<0.001), respectively.

Table 2.

Cox proportional HR of pneumonia between patients with IMRF (N=709) and non-traumatic patients (N=5672)

| 95% CI |

95% CI |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | Number of pneumonia event | Crude HR |

Lower | Upper | Adjusted HR | Lower | Upper | |

| Group | ||||||||

| Non-traumatic patients | 5672 | 10 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| IMRF | 709 | 11 | 8.86** | 3.76 | 20.86 | 8.94** | 3.79 | 21.09 |

| Age on index date (years) | ||||||||

| <65 | 4427 | 6 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≧65 | 1954 | 15 | 5.68** | 2.20 | 14.64 | 5.60** | 1.97 | 15.89 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 2534 | 5 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Male | 3847 | 16 | 2.11 | 0.77 | 5.76 | 2.35 | 0.85 | 6.55 |

| Diabetes | 926 | 3 | 0.98 | 0.29 | 3.33 | 0.57 | 0.16 | 2.04 |

| Hypertension | 1784 | 8 | 1.59 | 0.66 | 3.83 | 0.87 | 0.32 | 2.37 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 520 | 2 | 1.19 | 0.28 | 5.09 | 0.94 | 0.20 | 4.31 |

| Asthma | 270 | 1 | 1.13 | 0.15 | 8.45 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 2.59 |

| COPD | 365 | 7 | 8.29** | 3.35 | 20.54 | 5.41** | 2.01 | 14.55 |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IMRF, isolated minor ribs fractures.

Table 3.

Cox proportional HR of pneumonia in IMRF subgroups

| 95% CI |

95% CI |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | Number of pneumonia event | Crude HR | Lower | Upper | Adjusted HR† | Lower | Upper | |

| Group | ||||||||

| Non-traumatic patients | 5672 | 10 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Number of IMRF=1 | 476 | 3 | 3.58 | 0.99 | 13.02 | 3.97* | 1.09 | 14.44 |

| Number of IMRF=2 | 233 | 8 | 19.75** | 7.80 | 50.05 | 17.13** | 6.66 | 44.04 |

| IMRF (N=709) | ||||||||

| 1 | 476 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2 | 233 | 8 | 5.51* | 1.46 | 20.76 | 4.76* | 1.24 | 18.23 |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01.

†Adjusted for age, gender, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, asthma and COPD.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IMRF, isolated minor rib fractures.

Table 4 presents the characteristics of patients with IMRFs who were and were not hospitalised. Patients hospitalised for IMRFs had significant underlying comorbidities, such as hypertension (p=0.022) and cardiovascular disease (p=0.015). However, the risk of delayed pneumonia did not significantly differ in patients admitted or not admitted to hospitals (p=0.313).

Table 4.

Analysis of patients with IMRF with and without hospitalisation

| IMRF with hospitalisation N=207 |

IMRF without hospitalisation N=502 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Per cent | n | Per cent | p Value | |

| Age on index date | |||||

| Mean±SD | 56.7±16.2 | 54.9±15.7 | 0.176 | ||

| Gender | 0.012* | ||||

| Female | 66 | 31.9 | 211 | 42.0 | |

| Male | 141 | 68.1 | 291 | 58.0 | |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Diabetes | 38 | 18.4 | 66 | 13.1 | 0.075 |

| Hypertension | 69 | 33.3 | 125 | 24.9 | 0.022* |

| Cardiovascular disease | 25 | 12.1 | 33 | 6.6 | 0.015* |

| Asthma | 12 | 5.8 | 18 | 3.6 | 0.184 |

| COPD | 17 | 8.2 | 26 | 5.2 | 0.124 |

| Pneumonia | 5 | 2.4 | 6 | 1.2 | 0.313 |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IMRF, isolated minor rib fractures.

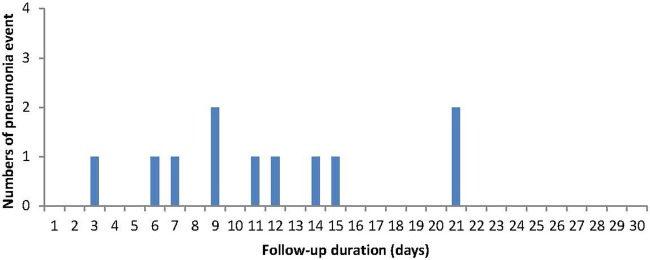

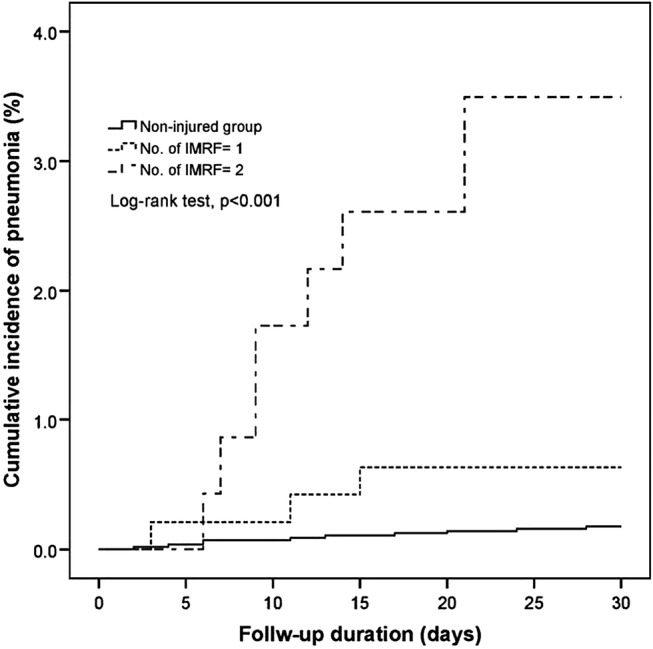

Figure 2 illustrates the time elapsed from IMRFs to subsequent pneumonia. More than 72.7% (8/11) of the patients developed pneumonia within 2 weeks after IMRFs. Figure 3 depicts the Kaplan-Meier curves for the occurrence of pneumonia in the non-traumatic patients and patients with IMRFs. The cumulative incidence of pneumonia was higher in patients with IMRFs than in non-traumatic patients throughout the 30-day follow-up period. The log-rank test findings revealed significant differences (p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Time elapsed between rib fractures and development of pneumonia. IMRF, isolated minor rib fractures.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves of the cumulative incidence of pneumonia in patients with isolated rib fractures and non-traumatic patients.

Discussion

In this nationwide population-based study, the incidence of pneumonia following IMRFs was 1.6%. Although this low incidence is similar to that reported in Canada (0.6%),11 our study demonstrated a high aHR of 8.94 (95% CI 3.79 to 21.09) for pneumonia in patients with IMRFs. Furthermore, old age (≥65 years; aHR=5.60 (95% CI 1.97 to 15.89)) and COPD (aHR=5.41, 95% CI 1.02 to 3.59) were risk factors for pneumonia after IMRFs.

The possible pathophysiology for developing pneumonia after IMRFs is discussed herein. First, pain caused by IMRFs can impair the coughing function and secretion clearance, which would reduce respiratory effort and lead to atelectasis and subsequent pneumonia. Elderly patients are highly susceptible to IMRFs because of inadequate physiological reserves and poor functional residual capacity.22 Pre-existing comorbidities and low immunity and frailty are the possible contributing factors to infection in the elderly patients. Bulger et al demonstrated that of the 464 patients with rib fractures, pneumonia occurred in 31% and 17% elderly and young patients, respectively. Furthermore, the incidence of pneumonia reached 51% in elderly patients with more than six rib fractures.23 Pre-existing comorbidities, such as congestive heart failure, ischaemic heart disease, COPD, diabetes and cirrhosis have been reported as well-known contributing factors for morbidity in elderly patients.22 24 Therefore, aggressive treatment of pain is crucial for rib fracture management in elderly patients. Adequate analgesia and breathing exercises have reduced the number of ventilator days and pneumonia incidence rates.25–27

Second, rib fractures are typically accompanied by pulmonary contusions after blunt chest traumas.28 29 Furthermore, chest contusion was reported as the most common occult injury during chest traumas.30 However, the incidence of pulmonary contusions, which were verified using CT, in patients with IMRFs was merely 0.6% (4/704) in our study and none of these patients developed delayed pneumonia. The true incidence of pulmonary contusion may be underestimated because only 19.5% of the patients with IMRFs underwent CT examinations. Furthermore, pulmonary contusions were not observed in the 11 patients who developed pneumonia in the IMRF group.

A systematic review and meta-analysis reported that pre-existing comorbidities, particularly cardiopulmonary disease and pneumonia, were risk factors for mortality following blunt chest traumas.31 Our study observed that only patients with pre-existing COPD without asthma or cardiovascular disease were at an increased risk of subsequent pneumonia after IMRFs. Patients with rib fractures having underlying lung diseases, such as COPD or asthma, were more susceptible to lung function impairment.32 Furthermore, patients with rib fractures having a vital capacity of <30% were at an increased risk of pulmonary complications.33 Moreover, lung function impairment can occur because of rib fractures and underlying pulmonary disease. In this study, we demonstrated that only COPD was associated with subsequent pneumonia after IMRFs.

The strength of this cohort study was the use of the nationwide database, LHID2010, including data of 1 million insureds randomly selected from the 2010 Registry of Beneficiaries. Taiwan's NHI system, established in 1995, covers the medical expenses of ∼98% of the Taiwanese population, thus providing accurate data of medical conditions in Taiwan. However, our study had several limitations. First, we could only obtain the number of patients with rib fractures experienced from the data sets and information on the type of rib fractures was not obtained. Fractures of the first 3 ribs indicated a high-energy injury that may lead to increased complications. However, Ziegler et al9 reported that the number of rib fractures and incidence of pulmonary complications, including pneumothorax, haemothorax, lung contusions and pneumonia, were not correlated. Second, the NHIRD does not provide the mechanism of injury or detailed clinical parameters, such as the injury severity score, abbreviated injury scale and laboratory data of the patients. Rib fractures sustained from high-energy traumas have a higher incidence of pulmonary contusions and other pulmonary traumas, which potentially pose a greater risk of pneumonia, than those sustained from low-energy traumas. Moreover, injury severity was reported to be a risk factor for pneumonia in patients with multiple rib fractures.21 Since we selected only patients with isolated single or two rib fractures, the trauma scores were low. Third, only 19% of the patients with IMRFs were diagnosed on the basis of both chest X-ray and CT examinations. Routine chest CT is not necessary in minor chest injury. However, up to 50% of rib fractures may be missed on a standard chest radiograph; therefore, the incidence of pneumonia after IMRFs might be overestimated in our study.22 Fourth, propensity score matching used probability values for pairing the IMRF and control groups. Only the independent variables in pairing between the two groups were considered for reducing the existing differences; however, other independent variables that may affect the final results were not considered. Therefore, the results after pairing may exhibit significant differences between the groups. Moreover, the pairing method is suitable for large sample studies, and small sample studies with inadequate sample sizes may lead to selection bias. Fifth, 29.2% patients were admitted to hospitals after being diagnosed with IMRFs in our study. Different countries and ED settings have different disposition practices; therefore, the present findings should be cautiously interpreted and generalised to other countries. Finally, the shortcomings of the retrospective methodology used in this study should be considered.

Conclusion

The incidence of pneumonia following IMRFs was low. Moreover, patients with two isolated rib fractures were particularly susceptible to pneumonia. Physicians should focus on this complication, particularly in elderly patients and those with COPD. We recommend that patients with single or two rib fractures should receive attentive follow-up care.

Footnotes

Contributors: S-WH and C-BY conceived and designed the experiments. S-FY, Y-HT and Y-HW analysed the data. H-WY and M-CC contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. S-WH and C-BY wrote the paper.

Funding: This study was based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, and managed by the National Health Research Institutes (registered number: NHIRD-102-158). The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of the National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare or National Health Research Institutes. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board of Chung Shan Medical University Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Matsuse H, Yanagihara K, Mukae H et al. . Association of plasma neutrophil elastase levels with other inflammatory mediators and clinical features in adult patients with moderate and severe pneumonia. Respir Med 2007;101:1521–8. 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prina E, Ranzani OT, Torres A. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet 2015;386:1097–108. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60733-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Millett ER, Quint JK, Smeeth L et al. . Incidence of community-acquired lower respiratory tract infections and pneumonia among older adults in the United Kingdom: a population-based study. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e75131 10.1371/journal.pone.0075131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.File TM Jr, Marrie TJ. Burden of community-acquired pneumonia in North American adults. Postgrad Med 2010;122:130–41. 10.3810/pgm.2010.03.2130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;385:117–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benjamin E, Haltmeier T, Chouliaras K et al. . Witnessed aspiration in trauma: frequent occurrence, rare morbidity—a prospective analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015;79:1030–7. 10.1097/TA.0000000000000704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pitts SR, Niska RW, Xu J et al. . National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2006 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Report 2008;7:1–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lien YC, Chen CH, Lin HC. Risk factors for 24-hour mortality after traumatic rib fractures owing to motor vehicle accidents: a nationwide population-based study. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;88:1124–30. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziegler DW, Agarwal NN. The morbidity and mortality of rib fractures. J Trauma 1994;37:975–9. 10.1097/00005373-199412000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byun JH, Kim HY. Factors affecting pneumonia occurring to patients with multiple rib fractures. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;46:130–4. 10.5090/kjtcs.2013.46.2.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chauny JM, Emond M, Plourde M et al. . Patients with rib fractures do not develop delayed pneumonia: a prospective, multicenter cohort study of minor thoracic injury. Ann Emerg Med 2012;60:726–31. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galan G, Penalver JC, Paris F et al. . Blunt chest injuries in 1696 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1992;6:284–7. 10.1016/1010-7940(92)90143-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanidas E, Kafetzakis A, Valassiadou K et al. . Management of simple thoracic injuries at a level I trauma centre: can primary healthcare system take over? Injury 2000;31:669–75. 10.1016/S0020-1383(00)00084-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu MS, Huang YK, Liu YH et al. . Delayed pneumothorax complicating minor rib fracture after chest trauma. Am J Emerg Med 2008;26:551–4. 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plourde M, Emond M, Lavoie A et al. . Cohort study on the prevalence and risk factors for delayed pulmonary complications in adults following minor blunt thoracic trauma. CJEM 2014;16:136–43. 10.2310/8000.2013.131043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emond M, Sirois MJ, Guimont C et al. . Functional impact of a minor thoracic injury: an investigation of age, delayed hemothorax, and rib fracture effects. Ann Surg 2015;262:1115–22. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shields JF, Emond M, Guimont C et al. . Acute minor thoracic injuries: evaluation of practice and follow-up in the emergency department. Can Fam Physician 2010;56:e117–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daoust R, Emond M, Bergeron E et al. . Risk factors of significant pain syndrome 90 days after minor thoracic injury: trajectory analysis. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:1139–45. 10.1111/acem.12248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elmistekawy EM, Hammad AA. Isolated rib fractures in geriatric patients. Ann Thorac Med 2007;2:166–8. 10.4103/1817-1737.36552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnea Y, Kashtan H, Skornick Y et al. . Isolated rib fractures in elderly patients: mortality and morbidity. Can J Surg 2002;45:43–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergeron E, Lavoie A, Clas D et al. . Elderly trauma patients with rib fractures are at greater risk of death and pneumonia. J Trauma 2003;54:478–85. 10.1097/01.TA.0000037095.83469.4C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brasel KJ, Guse CE, Layde P et al. . Rib fractures: relationship with pneumonia and mortality. Crit Care Med 2006;34:1642–6. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000217926.40975.4B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bulger EM, Arneson MA, Mock CN et al. . Rib fractures in the elderly. J Trauma 2000;48:1040–6; discussion 1046–1047 10.1097/00005373-200006000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris JA Jr, MacKenzie EJ, Edelstein SL. The effect of preexisting conditions on mortality in trauma patients. JAMA 1990;263:1942–6. 10.1001/jama.1990.03440140068033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wisner DH. A stepwise logistic regression analysis of factors affecting morbidity and mortality after thoracic trauma: effect of epidural analgesia. J Trauma 1990;30:799–804; discussion 804–795 10.1097/00005373-199007000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carrier FM, Turgeon AF, Nicole PC et al. . Effect of epidural analgesia in patients with traumatic rib fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Anaesth 2009;56:230–42. 10.1007/s12630-009-9052-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Y, Young JB, Schermer CR et al. . Use of ketorolac is associated with decreased pneumonia following rib fractures. Am J Surg 2014;207:566–72. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blasinska-Przerwa K, Pacho R, Bestry I. The application of MDCT in the diagnosis of chest trauma. Pneumonol Alergol Pol 2013;81:518–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kea B, Gamarallage R, Vairamuthu H et al. . What is the clinical significance of chest CT when the chest x-ray result is normal in patients with blunt trauma? Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:1268–73. 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langdorf MI, Medak AJ, Hendey GW et al. . Prevalence and clinical import of thoracic injury identified by chest computed tomography but not chest radiography in blunt trauma: Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Emerg Med 2015;66:589–600. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Battle CE, Hutchings H, Evans PA. Risk factors that predict mortality in patients with blunt chest wall trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury 2012;43:8–17. 10.1016/j.injury.2011.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis KA, Fabian TC, Croce MA et al. . Prostanoids: early mediators in the secondary injury that develops after unilateral pulmonary contusion. J Trauma 1999;46:824–31; discussion 831–822 10.1097/00005373-199905000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Machado-Aranda D, V Suresh M, Yu B et al. . Alveolar macrophage depletion increases the severity of acute inflammation following nonlethal unilateral lung contusion in mice. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014;76:982–90. 10.1097/TA.0000000000000163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]