Abstract

Objectives

To summarise the evidence for generic prognostic factors across a range of musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions.

Setting

primary care.

Methods and outcomes

Comprehensive systematic literature review. MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsychINFO and EMBASE were searched for prospective cohort studies, based in primary care (search period—inception to December 2015). Studies were included if they reported on adults consulting with MSK conditions and provided data on associations between baseline characteristics (prognostic factors) and outcome. A prognostic factor was identified as generic when significantly associated with any outcome for 2 or more different MSK conditions. Evidence synthesis focused on consistency of findings and study quality.

Results

14 682 citations were identified and 78 studies were included (involving more than 48 000 participants with 18 different outcome domains). 51 studies were on spinal pain/back pain/low back pain, 12 on neck/shoulder/arm pain, 3 on knee pain, 3 on hip pain and 9 on multisite pain/widespread pain. Total quality scores ranged from 5 to 14 (mean 11) and 65 studies (83%) scored 9 or more. Out of a total of 78 different prognostic factors for which data were provided, the following factors are considered to be generic prognostic factors for MSK conditions: widespread pain, high functional disability, somatisation, high pain intensity and presence of previous pain episodes. In addition, consistent evidence was found for use of pain medications not to be associated with outcome, suggesting that this factor is not a generic prognostic factor for MSK conditions.

Conclusions

This large review provides new evidence for generic prognostic factors for MSK conditions in primary care. Such factors include pain intensity, widespread pain, high functional disability, somatisation and movement restriction. This information can be used to screen and select patients for targeted treatment in clinical research as well as to inform the management of MSK conditions in primary care.

Keywords: Prognosis, Prognostic Factors, PRIMARY CARE, Systematic review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A large comprehensive review—14 682 citations identified, 78 studies included (more than 48 000 participants with 18 different outcome domains).

The first review to summarise evidence for individual generic prognostic factors for musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions.

A focus on primary care—but it is in this setting where MSK conditions are most commonly managed, and it is the primary care clinicians who would benefit most from using the concept of generic prognostic factors in discussing and planning the management with patients.

Inability to perform a meaningful meta-analysis—heterogeneity of outcome measures, with different measuring tools, differing measuring property and different follow-up points.

Introduction

Musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions, such as back pain and knee pain, are common presentations in primary care making up to one-third of all primary care consultations.1 2 They are the leading cause of disability worldwide3 and represent a burden on the individual, healthcare systems and society that is expected to increase in the coming years as people live longer.4 This has led to a growing interest in the prognosis of these conditions, to understand symptom progression and identify distinct patterns of symptom trajectories. In the absence of clear underlying aetiological mechanisms or strong evidence for large treatment effects5 information about the prognosis of MSK conditions becomes even more important in their management.6

Prognostic factors have been defined as characteristics that are associated with clinical outcomes in patients with a given health condition.7 Identifying prognostic factors and developing prognostic models can help predict the individual patient's outcome.8 An example is the presence of multisite MSK pain which has been found to be associated with poor future outcomes of psychological health, functional limitations and work disability.9–11 Prognostic factors that are found to be associated with treatment effect (effect modifiers or moderators) can potentially help predict response to specific treatments, and allow better targeting of treatments to those who are most likely to benefit or experience least harm from it (stratified medicine). For example, prognostic tools can be used to stratify patients with low back pain into ‘risk groups’ for whom particular treatments are shown to be most beneficial.12 13

Although prognostic factors have been described for a wide range of MSK conditions, they have often been studied for individual regional symptoms, such as back, neck or elbow pain.14–16 While there are differences in the presentation and likely underlying pathology, evidence suggests that MSK conditions often share a similar clinical course on average, and similar prognostic factors may predict outcome.17 Furthermore, nearly half of people with MSK conditions report pain in more than one site.11 18 19 For these reasons, it would be particularly useful to look for prognostic factors across a range of MSK conditions, regardless of their anatomical site or assumed pathological origin.20 In 2007, a systematic review21 explored this, and was able to evidence the presence of such ‘generic’ factors across a number of regional MSK conditions identified in individual studies. Since 2007, many more individual studies have been published reporting prognostic factors for various regional MSK conditions. Combining findings from these studies might help strengthen the evidence for generic factors, as identified in the original review, and identify other factors not yet identified.

Our aim was to systematically summarise the evidence from studies that investigated prognostic factors for MSK conditions in primary care, building and expanding on the previous review by Mallen et al.21 The objectives are to extract data on prognostic factors from included studies and synthesise the evidence for generic prognostic factors defined as a factor that was found to be significantly associated with outcome for two or more different regional MSK conditions, regardless of the number of studies in which this was assessed.

Methods

Literature search and study selection

We used the same search strategy as the systematic review of generic prognostic factors for MSK conditions by Mallen et al21 (see online supplementary appendix 1). We searched the computerised bibliographic databases of MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsychINFO and EMBASE for studies published from the end date of the search of the previous review (April 2006)21 to December 2015. The search combined terms for prognostic studies (eg, prognosis, course), MSK conditions (eg, neck, shoulder, hand, back, joint) and primary care (eg, general practice, family physician).

bmjopen-2016-012901supp_appendix1.pdf (204.8KB, pdf)

Eligible studies had to be prospective cohort studies, based in primary care or equivalent (direct access) healthcare settings and included adults consulting with regional MSK pain (joint, site-specific or multiple-site). They had to provide data on a measure of association between baseline characteristics (prognostic factors) and outcome. Excluded were studies among patients with inflammatory pain conditions (eg, gout, polymyalgia rheumatica) and studies only involving the analysis of medical records, and secondary analyses of data from randomised controlled trials. Studies published in English were considered for inclusion. When multiple articles for a single study were identified, information was extracted from all published articles.

Identified citations and abstracts were shared equally (50% each) by two authors (PC and MA) and screened independently for eligibility. Full texts of potentially eligible articles were then retrieved and again shared by the same two authors and reviewed for eligibility independently. The two authors (PC and MA) then retrieved a random selection of 10 articles which they both screened in order to check consistency on inclusion eligibility.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Included articles were shared by two authors (PC and MA) and data extraction and quality assessment conducted independently. Consistency of data extraction and quality assessment was checked on a random sample of 10 papers prior to the main data extraction. The findings reported in this review are from all studies included in the earlier and the current reviews combined.

The following information was extracted from each included article: first author, publication date, setting and country, sample size and participants' age and gender, anatomical pain site, primary outcome measures, and frequency and duration of follow-up. Other information included pain site and potential prognostic factors (participant's demographics and pain characteristics). Details of the association between potential prognostic factors and outcome were also collected, including the strength of association (eg, OR, relative risk (RR), difference in mean outcome scores), significance level and adjustment for covariates.

The same tool for assessing the quality of included studies used in Mallen et al21 was used here. This is a checklist consisting of 15 items that cover aspects related to internal and external validity. Items were scored positive (+) if present and satisfactory, negative (–) if absent or unsatisfactory, and unclear (?) if the article did not contain enough information to make an accurate assessment. The final quality score for individual studies was based on the sum of the positive scores. Although there are arguments against the use of summary quality scores for individual studies,22 we decided, with caution, to use summary scores to facilitate our evidence synthesis, which takes study quality into account when summarising results regarding generic prognostic factors across studies. To estimate the influence of using a predefined cut-point for identifying high-quality studies, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to explore the use of other cut-points (see below).

Evidence synthesis

The review focussed on identifying generic prognostic factors for MSK conditions in primary care. A potentially generic prognostic factor was defined as a factor that was found to be significantly associated with outcome for two or more different regional MSK conditions, for example, hip and shoulder pain, regardless of the number of studies in which this was assessed. Wide heterogeneity of study populations, treatments received and outcome measures precluded meta-analysis, and therefore evidence was synthesised taking into account statistical significance of associations, consistency of results and study quality.

Significant association with outcome was defined as a univariable association, or an association adjusted for confounding or other prognostic variables, with a p value <0.05, or an OR or RR with 95% CIs not including 1. Results were considered to be consistent if ≥75% of the studies reporting on the factor showed the same direction of the association with outcome. For study quality, an a priori decision was made to use a cut-off of more than 9 out of a total of 15 (60%) to define a study as ‘high quality’ versus a score of 9 or less for ‘low quality’.

Four levels of evidence were adapted from Sackett et al23 and Ariens et al24 which take into account consistency of significant results as well as methodological quality (table 1).

Table 1.

Levels of evidence for generic prognostic factors for poor outcome for musculoskeletal pain

| Level of evidence | Definition |

|---|---|

| Strong | Consistent significant findings (≥75%) in studies of high quality, at least 2 studies |

| Moderate | Consistent significant findings (≥75%) in studies of high and low quality with at least one study of high quality in the direction of consistent significant findings |

| Weak | Significant findings of only one study of high quality or consistent significant findings (≥75%) in studies of low quality |

| Inconclusive | Significant findings in less than 3 studies of low quality, or inconsistent significant findings (regardless of quality) |

Only factors assessed at baseline or at initial consultation were considered for analysis. When studies included multiple outcomes or different outcome domains (such as return to work, pain persistence), or different follow-up points (eg, 6 months and 1 year), any statistically significant association with any outcome at any follow-up time was taken as evidence for the factor's potential prognostic value.

With regard to defining MSK pain regions, a pragmatic approach was adopted to group studies according to the pain regions they described, to reduce duplication and to replicate the approach adopted in the review by Mallen et al.21 Studies on neck, shoulder and arm pain were grouped together. Studies on ‘spinal pain’, ‘back pain’ and ‘low back pain’ were grouped together because studies on ‘spinal pain’ and ‘back pain’ often included patients who had lower as well as upper back pain without distinction. Studies that described their patients as having ‘MSK pain’ or ‘joint pain’ without specifying a region were grouped together with studies that explicitly included patients with ‘multisite pain’ or ‘widespread pain’. If a single study included groups of patients each with a different regional pain complaint, potentially generic prognostic factors were identified separately for each of those pain groups if such information was provided separately in the article.

Sensitivity analyses

To assess the robustness of our evidence synthesis, a number of sensitivity analyses were carried out. To examine the influence of using a cut-point for study quality, analysis was carried out on different quality cut-offs: a lower cut-off of 50% (total score of 7.5) and higher cut-off of 75% (total score of 11). Results were also examined regardless of study quality score. To assess whether the synthesised overall evidence was influenced by study sample size, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by repeating the analyses, but excluding studies with small sample size. As there is no consensus on what defines a small observational study, two arbitrary cut-off sample size values of 100 and 200 participants were used for this purpose.

Results

Study selection

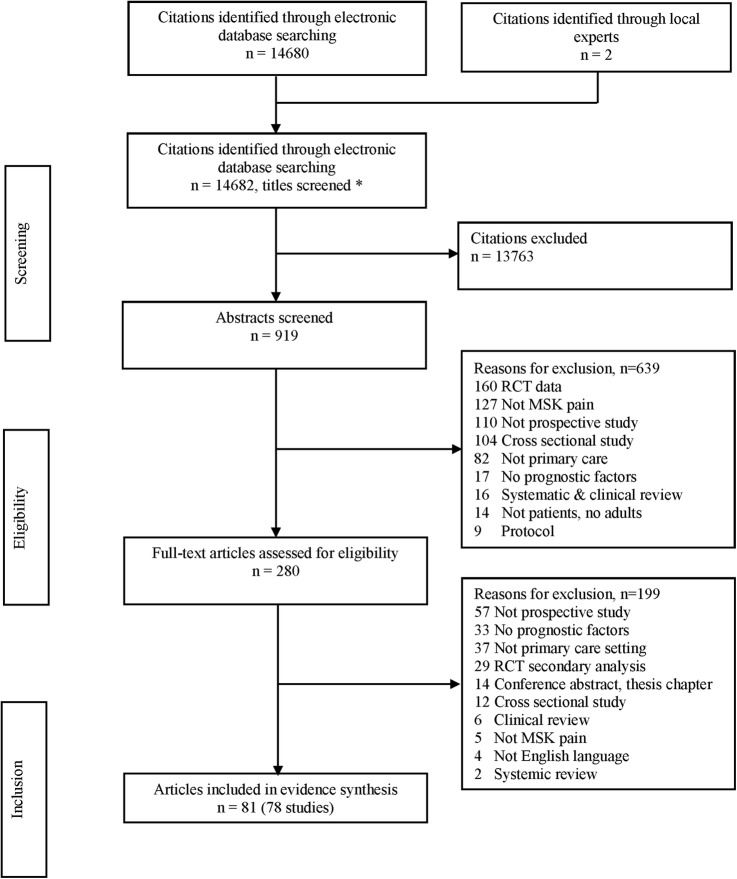

In total, 14 682 independent citations were identified in the systematic electronic search (figure 1). In total, 13 763 were excluded on screening of titles and further 639 on screening abstracts. Eighty-one full articles reporting on 78 studies met all selection criteria and were included in the review. This included the 45 articles included in the earlier review.21

Figure 1.

Results of literature search and study selection. MSK, musculoskeletal; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Study characteristics

The 78 included studies were conducted in Australia, North America and Europe, and investigated prognostic factors for MSK pain among more than 48 000 patients in primary care (individual study size ranging from 44 to 4325 patients). In total, 51 studies were on spinal pain/back pain/low back pain, 12 on neck/shoulder/arm pain, 3 on knee pain, 3 on hip pain and 9 on multisite pain/widespread pain. Characteristics of the included studies are presented in online supplementary appendix 2 and citations in online supplementary appendix 3.

bmjopen-2016-012901supp_appendix2.pdf (268.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012901supp_appendix3.pdf (212.5KB, pdf)

Overall, 18 different outcome domains were used; the most frequently used were physical functioning (in 37 studies) and pain severity (in 23 studies). However, various outcome measures were used within these domains. For physical functioning, measures included the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), the Oswestry Disability Inventory (ODI), and the Medical Outcome Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36). For pain severity, measures included Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), days with pain and 1–7 point ordinal scale. In addition, composite scales were used for pain and physical functioning, such as the Chronic Pain Grade (CPG) questionnaire, the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) and the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI). Outcomes within the domain of return to work were used in 17 studies (return to work in good health, days of sick leave, absence from work, ability to work), patient perceived recovery in 10 (global perceived recovery, global perceived effect), persistence of symptoms in 11 and use of healthcare services and medications in 7 studies. Recurrence of the symptom was used in two studies. Each of the following outcomes were used in one study each: neck pain questionnaire, survival, time to general practitioner visit, presence of knee pain, receiving acupuncture, catastrophising, pain-related fear, recovery expectation, quality of life and hip replacement. Length of follow-up ranged from 2 weeks to 10 years (median 12 months, mean 18 months). Owing to the diversity of outcome measures used in the studies, the tools to measure them, the properties of those tools and the time points they were measured at, it was not possible to conduct separate analyses for associations with specific outcome measures.

Quality of included studies

Information was provided by the included studies to allow for assessment of the majority of quality items (table 2). Items for which there was sufficient information and were considered satisfactory most frequently are ‘standardised collection of data’ and ‘appropriate design for the study question’ (each in 77 studies, 99%). The quality item that was considered unsatisfactory most frequently was ‘sample size calculation’, which was missing or inappropriate in all but one study.25 Information was unclear for some quality items, most frequently baseline participation of more than 70% of study sample (unclear in 28 studies (36%) and representativeness of the study sample (unclear in 12 studies (15%)).

Table 2.

Number of studies in which information on individual methodological quality assessment items was satisfactory, unsatisfactory or unclear

| Quality item | Yes | No | Unclear |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standardised collection of data | 77 | 0 | 1 |

| Appropriate design for study question | 77 | 0 | 1 |

| Clearly defined study objective | 76 | 1 | 1 |

| Appropriate selection of outcome | 75 | 2 | 1 |

| Appropriate analysis of outcomes measured | 73 | 2 | 3 |

| Appropriate measure of outcome | 71 | 4 | 3 |

| Numerical description of important outcomes given | 68 | 9 | 1 |

| Adequate length of follow-up for research question | 67 | 9 | 2 |

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria clear and appropriate | 61 | 12 | 4 |

| Representative sample (and comparison) | 61 | 5 | 12 |

| Losses and drop outs <20% | 49 | 24 | 5 |

| Adjusted and unadjusted calculations provided (with CI if appropriate) | 44 | 31 | 3 |

| Adequate description of losses and drop outs | 42 | 33 | 3 |

| Baseline participation >70% (all groups) | 32 | 18 | 28 |

| Sample size calculation provided | 1 | 77 | 0 |

Total quality scores for individual studies ranged from 5 to 14 (mean 11, median 11). Out of a possible maximum score of 15 (all quality items satisfied), 65 studies (83%) scored more than 9 points and were considered as high-quality studies (see online supplementary appendix 4).

bmjopen-2016-012901supp_appendix4.pdf (232.8KB, pdf)

Prognostic factors

Information on a total of 78 different prognostic factors was provided in at least one of the included studies (table 3).

Table 3.

Prognostic factors that were investigated in the included studies

| 1. Abdominal pain | 40. Leg pain |

| 2. Activity avoidance | 41. Living with a partner |

| 3. Age | 42. Monotonous repetitive work |

| 4. Aggressiveness | 43. Neurological signs |

| 5. Back surgery | 44. Pain better at rest |

| 6. BMI | 45. Pain control |

| 7. Bone density | 46. Pain in thoracic area |

| 8. Bothersomeness | 47. Pain intensity |

| 9. Catastrophising | 48. Pain medication |

| 10. Comorbidity | 49. Pain on examination |

| 11. Compensation | 50. Patient beliefs |

| 12. Consultation for knee pain | 51. Pay scale |

| 13. Coping | 52. Perceived cause as accident or trauma |

| 14. Decision authority | 53. Perceived disability |

| 15. Depression/anxiety | 54. Perceived risk of persistence |

| 16. Disability | 55. Perceived self-efficacy |

| 17. Drinking coffee | 56. Persistence of pain |

| 18. Duration | 57. Previous treatment |

| 19. Education | 58. Quadriceps strength |

| 20. Employment | 59. Recurrence |

| 21. Ethnicity | 60. Resilience |

| 22. Expectation of recovery | 61. Responses of important others |

| 23. Fear avoidance | 62. Satisfaction with management |

| 24. Financial impact of LBP | 63. Self-reported health (poor) |

| 25. Frailty | 64. Sleep quality |

| 26. Gender | 65. Smoking |

| 27. GP advice wait and see | 66. Social support |

| 28. GP advise physical exercise | 67. Socioeconomic status |

| 29. GP estimation of risk | 68. Somatisation |

| 30. GP improve posture advice | 69. Specific diagnosis |

| 31. Hand grip strength | 70. Sport, physical activity |

| 32. Headache | 71. The physician listened carefully |

| 33. Heavy lifting | 72. Physical trauma |

| 34. Hypochondriasis | 73. Waist circumference |

| 35. In unionised job | 74. Weak personal control |

| 36. Job satisfaction | 75. Widespread pain |

| 37. Job seniority | 76. Work ability |

| 38. Kinesiophobia | 77. Work absence |

| 39. Knee pain at follow-up | 78. Work security |

BMI, body mass index; GP, general practitioner; LBP, low back pain.

Sixty-three factors were investigated for only one pain region, and so evidence was not available for these factors to be considered as generic prognostic factors. For the other 15 factors, data were available for their association with outcomes for two or more pain regions, and were therefore considered as potential generic prognostic factors. The number of pain regions in which these 15 factors were studied ranged from 2 (for heavy lifting: back and shoulder) to 9 (for gender), in a number of studies ranging from 1 (for heavy lifting)26 to 45 (for pain duration). Table 4 lists the studies that provided evidence for each of the 15 potentially generic prognostic factors, grouped according to the regional MSK conditions they studied. Only two factors (social support and heavy lifting) were studied with regard to only two MSK conditions. All the remaining potential generic prognostic factors were from studies on four or more MSK pain sites.

Table 4.

Studies that provided evidence significant association between potentially generic prognostic factors and poor outcomes.

| Prognostic factors | Significant association | n | Neck/shoulder/arm (n 11) | Spinal/back (n 41) | Hip (n 3) | Knee (n 3) | General musculoskeletal (n 7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widespread pain, present | Yes | 20 | 14, 35, 36, 44, 48, 50, 69 | 15, 18, 21, 24, 33, 49, 52, 10 | − | 63 | 25, 57, 72, 78 |

| No | 6 | − | 51, 53, 61, 68 | − | 64 | 58 | |

| Disability, high | Yes | 18 | 12, 35, 36 |

2, 3, 9, 13, 15, 20, 24, 31, 33, 39 10, 22 |

28 | 42 | 26 |

| No | 2 | − | 45, 74 | − | − | − | |

| Somatisation, present | Yes | 12 | 35, 44, 48 | 15, 34, 38, 61, 70, 77, 10 | − | 42 | 22 |

| No | 2 | 69 | 67 | − | − | − | |

| Pain intensity, high | Yes | 27 | 14, 35, 36, 44, 48 | 8, 13, 15, 16, 24, 33, 34, 37, 39, 41, 45, 49, 53, 56, 65, 73, 10, 68 | 28 | 42 | 7, 26 |

| No | 12 | 50, 69 | 9, 18, 31, 61, 67, 74, 60 | 64 | 58, 78 | ||

| Pain duration, long | Yes | 31 | 12, 14, 35, 36, 44, 50, 69 | 2, 3, 8, 13, 15, 16, 18, 19, 21, 31, 33, 39, 45, 49, 56, 61, 66, 77, 1, 10, 60 | 28, 40 | 42 | − |

| No | 15 | 47, 48, 71 | 9, 20, 24, 38, 53, 65, 67, 70, 22, 68 | − | 63 | 57 | |

| Depression/anxiety, high | Yes | 17 | − | 6, 13, 15, 19, 34, 38, 49, 56, 73, 74, 10, 32 | − | − | 7, 23, 25, 58, 78 |

| No | 10 | 48 | 24, 60, 65, 66, 67, 70, 77, 68 | − | 64 | − | |

| Previous episodes, present | Yes | 16 | 12, 35, 36, 44, 75 | 3, 9, 19, 21, 34, 41, 49, 53, 61 | − | 42 | 57 |

| No | 11 | 47, 50, 71 | 20, 31, 38, 45, 51, 67, 68 | − | − | 7 | |

| Coping strategies, poor | Yes | 12 | 35, 36, 71 | 15, 49, 52, 53, 10, 32, 43 | − | − | 7, 78 |

| No | 6 | 69 | 61, 77, 60, 68 | − | − | 58 | |

| Movement restriction, present | Yes | 6 | 12 | 21, 29, 70 | 28 | − | 58 |

| No | 4 | − | 9, 20, 60 | − | − | 78 | |

| Level of education, low | Yes | 4 | − | 49, 61 | − | 63 | 57 |

| No | 11 | 69, 71 | 51, 56, 65, 66, 67, 68 | − | 64 | 58, 78 | |

| Use of pain medication | Yes | 2 | 71 | − | − | − | 57 |

| No | 6 | 50 | 51, 56, 66, 67 | 46 | − | − | |

| Age, older | Yes | 16 | 36, 35 | 8, 21, 33, 38, 41, 45, 56, 66, 67 | − | 42, 63 | 25, 58, 78 |

| No | 26 | 44, 48, 69, 71, 62 | 9, 18, 20, 24, 31, 49, 51, 53, 61, 65, 70, 77, 1, 22, 60, 62, 68 | 40, 46 | 64 | 7, 57 | |

| Gender, female | Yes | 5 | 50, 75 | 49, 66, 77 | − | − | − |

| No | 15 | 69, 71 | 51, 53, 61, 65, 67, 70, 68, 60 | 46 | 63, 64 | 57, 58 | |

| Social support, poor | Yes | 2 | 35 | − | − | 42 | − |

| No | 2 | − | 74 | − | − | 78 | |

| Heavy lifting, present | Yes | 1 | 62 | 62 | − | − | − |

| No | 0 | − | − | − | − | − |

*Citations of included studies are presented in online supplementary appendix 3.

Studies grouped according to pain site. High-quality studies are shown in bold.*

The overall level of evidence for each potential generic prognostic factor, taking into account the number of studies and their methodological quality, is presented in table 5.

Table 5.

Level of evidence for significant association of the potentially generic prognostic factors with poor outcomes and mean (range) of total quality scores for high-quality versus low-quality studies

| Association with poor outcome |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant association present |

Significant association absent |

||||||

| Prognostic factors | Quality n Quality score |

Quality n Quality score |

Overall evidence | ||||

| Widespread pain, present | High | 18 | 12 (11–14) | High | 4 | 11.5 (10–13) | Yes, associated, strong |

| Low | 2 | 9 | Low | 2 | 6.5 (5–8) | ||

| Disability, high | High | 16 | 12 (10–14) | High | 2 | 12 | Yes, associated, strong |

| Low | 2 | 9 | Low | 0 | − | ||

| Somatisation, present | High | 10 | 12 (10–14) | High | 2 | 12.5 (11–14) | Yes, associated, strong |

| Low | 2 | 9 | Low | 0 | |||

| Pain intensity, high | High | 25 | 12 (12–14) | High | 10 | 11.5 (10–14) | Yes, associated, moderate |

| Low | 2 | 8.5 (8–9) | Low | 2 | 6.5 (5–8) | ||

| Pain duration, long | High | 27 | 12 (10–14) | High | 12 | 12 (11–14) | Yes, associated, moderate |

| Low | 4 | 8 (8–9) | Low | 3 | 8.5 (8–9) | ||

| Depression/anxiety, high | High | 15 | 13 (10–14) | High | 8 | 12.5 (11–14) | Yes, associated. moderate |

| Low | 2 | 8.5 (8–9) | Low | 2 | 7 (5–8) | ||

| Previous episodes, present | High | 16 | 12 (10–13) | High | 10 | 12 (10–14) | Yes, associated, weak |

| Low | 0 | − | Low | 1 | 8 | ||

| Coping strategy, poor | High | 9 | 12 (10–14) | High | 4 | 11 (10–13) | Yes, associated, weak |

| Low | 3 | 8 (8–9) | Low | 2 | 8 | ||

| Movement restriction, present | High | 6 | 11.5 (10–13) | High | 3 | 11 | Yes, associated, weak |

| Low | 0 | − | Low | 1 | 8 | ||

| Level of education, low | High | 3 | 12 (10–13) | High | 9 | 12.5 (10–13) | Not associated, strong |

| Low | 1 | 9 | Low | 2 | 6.5 (5–8) | ||

| Use of pain medication | High | 2 | 12.5 (12–13) | High | 5 | 12.5 (11–14) | Not associated, moderate |

| Low | 0 | Low | 1 | 9 | |||

| Age, older | High | 15 | 12 (11–14) | High | 18 | 11.5 (10–13) | Not associated, weak |

| Low | 1 | 9 | Low | 8 | 7.5 (5–9) | ||

| Gender, female | High | 5 | 13 | High | 10 | 12 (10–14) | Not associated, weak |

| Low | 0 | − | Low | 5 | 8 (5–9) | ||

| Social support, poor | High | 2 | 13 | High | 2 | 13 | Inconclusive |

| Low | 0 | − | Low | 0 | − | ||

| Heavy lifting, present | High | 0 | − | High | 0 | − | Inconclusive |

| Low | 1 | 5 | Low | 0 | − | ||

Using both the number of studies providing evidence and their methodological quality, segregating studies according to the cut-off for high quality, strong evidence for being a generic prognostic factor indicating a poor prognosis was found for: widespread pain, high functional disability and somatisation. Evidence was moderate for high pain intensity, long pain duration and high depression/anxiety score and weak for history of previous pain episode, poor coping strategy and movement restriction. Strong evidence was also found from multiple high-quality studies for the absence of association between outcome and low level of education. Evidence for lack of association was moderate for use of pain medications and weak for older age and gender and therefore these factors are not generic prognostic factors. Evidence from the available studies was not conclusive for poor social support and heavy lifting.

The number of studies that provided evidence for each of the generic factors varied widely. For the factors for which evidence was conclusive, the number of studies providing the evidence ranged from 10 studies for movement restriction to 46 for pain duration (mean 20 studies, median 18). For the two factors for which evidence was considered inconclusive, four studies provided evidence for poor social support and only one study for heavy lifting.

Sensitivity analyses

Using a lower total study quality score cut-off of 50% (total score of 7.5) and higher cut-off of 75% (total score of 11) did not change the overall evidence for the generic prognostic factors. Moreover not including quality scores in summarising the overall evidence and only relying on the number of studies, in another sensitivity analysis, also did not change the overall evidence for the generic prognostic factors.

Regarding study sample size, using the lower cut-off sample size of 100 participants, only five of the included studies included <100 participants. These five studies, which were all scored as high quality, showed significant associations between outcomes and several prognostic factors (functional disability, pain intensity, pain duration, depression and anxiety, movement restriction, age). Excluding these studies did not influence the weight of evidence for the association between prognostic factors and outcomes.

Using the higher sample size cut-off of 200 participants, 24 studies would be identified as small (<200 participants). In total, 22/24 of these studies were of high quality and contributed evidence for significant association between outcomes and most potential generic prognostic factors. When excluding these 24 small studies from the evidence synthesis, evidence remained strong only for presence of widespread pain, high functional disability and somatisation as generic prognostic factors (see online supplementary appendix 5). In addition, overall evidence became consistent and therefore strong for high pain intensity and previous history of similar episode of pain.

bmjopen-2016-012901supp_appendix5.pdf (94.2KB, pdf)

Discussion

This comprehensive systematic review provides evidence for generic prognostic factors for across a range of MSK conditions in primary care. Based on 78 studies, the majority of which were of high methodological quality, the following factors are considered to be generic prognostic factors for MSK conditions: widespread pain, high functional disability, somatisation, high pain intensity and presence of previous pain episodes. In addition, consistent evidence was found for use of pain medications not to be associated with outcome, suggesting that this factor is not a generic prognostic factor for MSK conditions.

These findings are important. They are the product of a comprehensive search of the literature providing evidence from a large number of high-quality studies since an earlier review was published just under 10 years ago.21 The focus of this review was on primary care as it is in this setting where MSK conditions are most commonly managed, and it is the primary care clinicians who would benefit most from using the concept of generic prognostic factors in discussing and planning the management with patients. The large number of studies in this review, reflecting the growing interest in assessing prognosis of MSK pain, adds clarity and strength to identifying generic prognostic factors for MSK conditions. A recent systematic review limited to patients with subacute non-malignant pain, that also included studies on headache, provided evidence on the presence of generic prognostic factors.27 That review only assessed the association of prognostic factors with functional disability and absence from work. It found that multisite pain, high pain severity, older age, baseline disability and longer pain duration were identified as potential prognostic factors for disability, which has overlaps with the current findings. A cohort study among patients with non-spinal MSK pain20 is one of few studies that used direct ‘comparisons’ between prognostic factors and pain intensity outcome. It found that having had the same symptom in the previous year, a lower level of education, lower scores on the SF-36 vitality subscale, using pain medication at baseline and being bothered by the symptom more often in the past 3 months were associated with poor improvement in pain intensity over time regardless of the location of pain. The difference between these findings and ours might be explained by the fact that prognostic factors in these two studies were investigated only in association with specific outcomes. For the factor of age, we found evidence for association with outcomes in 15 studies, and for no association in 26. It is arguable that the findings related to this factor might be different if specific outcomes were selected, and similarly if different pain sites were selected. Our definition of generic prognostic factors was across all MSK conditions regardless of site or outcome measures.

The potential application and utility of prognostic factors for research and clinical practice is well recognised.7 They could help inform patients, clinicians and researchers about the likely course of the condition, and enable clinicians to identify patients at high or low risk of poor outcome to aid decisions on further investigations or more extensive treatment. Prognostic factors could also be used to enable clinicians to target specific types of treatment to particular patients with a particular prognostic profile. The STarT Back Tool is an example of such a tool that was found to be effective in managing patients with low back pain.13 Identifying subgroups of patients according to their prognostic profile would also enable better understanding and interpretation of response to treatment in clinical trials. Modifiable factors, such as movement restrictions or depression/anxiety, could represent potential targets for treatments investigated in clinical research. Other factors, such as presence of widespread pain or pain duration, could also be used to investigate differential treatment effects in subgroups of participants.

Generic prognostic factors, compared with individual prognostic factors for individual MSK conditions, have additional and arguably superior utility in that they help support a generic approach in research and clinical management. Targeting these factors as potential treatment effect modifiers or moderators is one example of such potential. Clinically, for patients presenting with shoulder, knee or back pain or a combination of these pains, for instance, trying to memorise and explore individual prognostic factors for each of these pain conditions assuming they are different and distinct, will at best be difficult and at worst confusing. Exploring generic factors that apply to any and all MSK conditions, regardless of pain region, helps focus the discussion between the clinician and the patient and the concluding message.

Apart from gender, age, level of education and use of pain medications, the remaining 55 factors that were studied but not considered as generic could not be completely ruled out as potential generic MSK prognostic factors. Evidence was not available to make this judgement, and high-quality studies need to examine their association with outcomes to provide such evidence.

The number of studies that investigated different MSK conditions varied considerably. Back pain was studied in the vast majority of studies, just under 70%, compared with 16% for neck/shoulder/arm pain and only 4% each for knee and hip and 10% on multisite/widespread pain. Although this reflects and represents the prevalence of these presentations in primary care,1 it also indicates a need to assess prognostic factors in these latter conditions to be able to safely conclude whether there are other potentially generic prognostic factors. Our sensitivity analyses showed that evidence for some generic prognostic factors was derived from small cohort studies and therefore less robust (in particular age, depression, coping strategies, movement restriction). Obtaining evidence from further larger, high-quality studies on these factors would also help strengthen the evidence for the generic prognostic factors we identified. Another area to explore in future research is to identify prognostic factors that might be found consistently associated with particular MSK pain condition but not with others. Such factors might be considered as specific for those MSK conditions.

Limitations

Including findings from clinical trials was considered, but as trial participants compared with those of observational studies are often highly selected, have different characteristics with different data collection methods and different types of treatment, often have different expectations regarding treatment, which we know may influence prognosis, and may therefore be more (or less) likely to take part in research. Also, treatment is closely controlled in trials and even usual care arms are not identical to actual care in most cases (they are often best care rather than usual care), and this may make a difference to the prognostic factors identified. Another potential point might be that trials only measure factors relevant to the trial, whereas cohort studies are more likely to explore a wide range of factors relevant to prognosis. So we might get a biased selection of prognostic factors if data were obtained from randomised controlled trials. All these would have potentially influenced our findings regarding prognosis and prognostic factors.

A limitation associated with the use of a list of quality items and total quality score, is the inability to discriminate between studies based on particular individual items, as some quality items would potentially have greater weighting in the assessment of bias. To investigate this potential limitation, a sensitivity analysis was performed using a different total score cut-off, which may have mitigated the issue of impact of individual items, although might not completely resolve it.

One challenge we faced in this review was the inability to perform a meaningful meta-analysis because of the heterogeneity of outcome measures, with different measuring tools, differing measuring property and different follow-up points. This deprived us of the ability to provide a quantitative estimate of the predictive performance of the generic prognostic factors for particular outcomes. It is arguable that some factors are generic for particular outcomes and not others. It would be plausible to expect some factors to be more strongly associated with outcomes than others. Equally, the strength of predictive performance of the factors might depend on the number of pain sites it is associated with. The results of this review help shed important light on a number of generic prognostic factors that need to be further studied in future research. A clearer understanding of the roles of these generic factors is an important next step and could be generated through meta-analysis of individual patient data from studies.

Conclusion

We have identified strong evidence to support the presence of a number of generic prognostic factors that are associated with poor outcomes for MSK conditions, regardless of pain site. Such factors include pain intensity, widespread pain, high functional disability, somatisation and movement restriction. This information can be incorporated into the management of MSK conditions in primary care.

Footnotes

Contributors: MA and PC conducted the systematic literature search, study inclusion, data extraction, study quality assessment and evidence synthesis. MA led writing the article and PC, KMD, CDM and DAWvdW contributed extensively to writing the manuscript.

Funding: Time from MA was supported by his NIHR Clinical Lectureship and an NIHR Research Professorship awarded to Nadine Foster (NIHR-RP-2011–015). CDM is funded by the NIHR Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care West Midlands, the NIHR School for Primary Care Research and an NIHR Research Professorship (NIHR-RP-2014-04-026). DAWvdW is a member of PROGRESS Medical Research Council Prognosis Research Strategy (PROGRESS) Partnership (G0902393/99558).

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Jordan KP, Kadam UT, Hayward R et al. Annual consultation prevalence of regional musculoskeletal problems in primary care: an observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010;11:144 10.1186/1471-2474-11-144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jordan KP, Jöud A, Bergknut C et al. International comparisons of the consultation prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions using population-based healthcare data from England and Sweden. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:212–18. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoy DG, Smith E, Cross M et al. The global burden of musculoskeletal conditions for 2010: an overview of methods. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:982–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks PM. The burden of musculoskeletal disease—a global perspective. Clin Rheumatol 2006;25:778–81. 10.1007/s10067-006-0240-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keller A, Hayden J, Bombardier C et al. Effect sizes of non-surgical treatments of non-specific low-back pain. Eur Spine J 2007;16:1776–88. 10.1007/s00586-007-0379-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croft P, Altman DG, Deeks JJ et al. The science of clinical practice: disease diagnosis or patient prognosis? Evidence about “what is likely to happen” should shape clinical practice. BMC Med 2015;13:20 10.1186/s12916-014-0265-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riley RD, Hayden JA, Steyerberg EW et al. , for the PROGRESS Group. Prognosis Research Strategy (PROGRESS) 2: prognostic factor research. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001380 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steyerberg EW, Moons KGM, van der Windt DA et al. , for the PROGRESS Group. Prognosis Research Strategy (PROGRESS) 3: prognostic model research. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001381 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamaleri Y, Natvig B, Ihlebaek CM et al. NPS is associated with demographic, lifestyle, and health-related factors in the general population. Eur J Pain 2008;12:742–8. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamaleri Y, Natvig B, Ihlebaek CM et al. Localized or widespread musculoskeletal pain: does it matter? Pain 2008;138:41–6. 10.1016/j.pain.2007.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamaleri Y, Natvig B, Ihlebaek CM et al. Does the number of musculoskeletal pain sites predict work disability? A 14-year prospective study. Eur J Pain 2009;13:426–30. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flynn T, Fritz J, Whitman J et al. A clinical prediction rule for classifying patients with low back pain who demonstrate short-term improvement with spinal manipulation. Spine 2002;27:2835–43. 10.1097/01.BRS.0000035681.33747.8D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill JC, Whitehurst DG, Lewis M et al. Comparison of stratified primary care management for low back pain with current best practice (STarTBack): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;378:1560–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60937-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costa L, Maher CG, Hancock MJ et al. The prognosis of acute and persistent low-back pain: a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2012;184:E613–24. 10.1503/cmaj.111271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walton DM, Carroll LJ, Kasch H et al. , ICON. An overview of systematic reviews on prognostic factors in neck pain: results from the International Collaboration on Neck Pain (ICON) Project. Open Orthop J 2013;7:494–505. 10.2174/1874325001307010494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bot SDM, van der Waal JM, Terwee CB et al. Course and prognosis of elbow complaints: a cohort study in general practice. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1331–6. 10.1136/ard.2004.030320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henschke N, Ostello RW, Terwee CB et al. Identifying generic predictors of outcome in patients presenting to primary care with non-spinal musculoskeletal pain. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:1217–24. 10.1002/acr.21665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartvigsen J, Davidsen M, Hestbaek L et al. Patterns of musculoskeletal pain in the population: a latent class analysis using a nationally representative interviewer-based survey of 4817 Danes. Eur J Pain 2013;17:452–60. 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rathleff MS, Roos EM, Olesen JL et al. High prevalence of daily and multi-site pain—a cross-sectional population-based study among 3000 Danish adolescents. BMC Pediatr 2013;13:191 10.1186/1471-2431-13-191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nahit ES, Hunt IM, Lunt M et al. Effects of psychosocial and individual psychological factor on the onset of musculoskeletal pain: common and site-specific effects. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:755–60. 10.1136/ard.62.8.755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mallen CD, Peat G, Thomas E et al. Prognostic factors for musculoskeletal pain in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:655–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL et al. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:280–6. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sackett DL, Straus SE, Richardson WS. Evidence-based medicine. How to practice and teach EMB. Edinburgh, Churchill Livingstone, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ariens GA, van Mechelen W, Bongers PM et al. Physical risk factors for neck pain. Scand J Work Environ Health 2000;26:7–19. 10.5271/sjweh.504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jellema P, van der Horst HE, Vlaeyen JWS et al. Predictors of outcome in patients with (sub) acute low back pain differ across treatment groups. Spine 2006;31:1699–705. 10.1097/01.brs.0000224179.04964.aa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen JC, Haahr JP, Frost P et al. Do work-related factors affect care-seeking in general practice for back pain or upper extremity pain? Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2013;86:799–808. 10.1007/s00420-012-0815-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valentin GH, Pilegaard MS, Vaegter HB et al. Prognostic factors for disability and sick leave in patients with subacute non-malignant pain: a systematic review of cohort studies. BMJ Open 2016;6:e007616 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012901supp_appendix1.pdf (204.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012901supp_appendix2.pdf (268.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012901supp_appendix3.pdf (212.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012901supp_appendix4.pdf (232.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012901supp_appendix5.pdf (94.2KB, pdf)