Abstract

Objective

To understand how prepared UK medical graduates are for practice and the effectiveness of workplace transition interventions.

Design

A rapid review of the literature (registration #CRD42013005305).

Data sources

Nine major databases (and key websites) were searched in two timeframes (July–September 2013; updated May–June 2014): CINAHL, Embase, Educational Resources Information Centre, Health Management Information Consortium, MEDLINE, MEDLINE in Process, PsycINFO, Scopus and Web of Knowledge.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

Primary research or studies reporting UK medical graduates' preparedness between 2009 and 2014: manuscripts in English; all study types; participants who are final-year medical students, medical graduates, clinical educators, patients or NHS employers and all outcome measures.

Data extraction

At time 1, three researchers screened manuscripts (for duplicates, exclusion/inclusion criteria and quality). Remaining 81 manuscripts were coded. At time 2, one researcher repeated the process for 2013–2014 (adding six manuscripts). Data were analysed using a narrative synthesis and mapped against Tomorrow's Doctors (2009) graduate outcomes.

Results

Most studies comprised junior doctors' self-reports (65/87, 75%), few defined preparedness and a programmatic approach was lacking. Six themes were highlighted: individual skills/knowledge, interactional competence, systemic/technological competence, personal preparedness, demographic factors and transitional interventions. Graduates appear prepared for history taking, physical examinations and some clinical skills, but unprepared for other aspects, including prescribing, clinical reasoning/diagnoses, emergency management, multidisciplinary team-working, handover, error/safety incidents, understanding ethical/legal issues and ward environment familiarity. Shadowing and induction smooth transition into practice, but there is a paucity of evidence around assistantship efficacy.

Conclusions

Educational interventions are needed to address areas of unpreparedness (eg, multidisciplinary team-working, prescribing and clinical reasoning). Future research in areas we are unsure about should adopt a programmatic and rigorous approach, with clear definitions of preparedness, multiple stakeholder perspectives along with multisite and longitudinal research designs to achieve a joined-up, systematic, approach to understanding future educational requirements for junior doctors.

Keywords: BASIC SCIENCES, EDUCATION & TRAINING (see Medical Education & Training), GENERAL MEDICINE (see Internal Medicine), INTENSIVE & CRITICAL CARE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A rigorous review using nine major databases resulting in a comprehensive narrative synthesis of 87 manuscripts.

Our rigorous approach has clearly identified areas where research is lacking and the need for programmatic research in this area.

The broad scope of what comprises preparedness, the lack of definitions in the literature and diversity in study designs and quality led to difficulties in ascertaining firm generalisable conclusions in some areas.

Many studies collected data immediately after graduation and focused purely on preparedness for graduates' first days as a junior doctor.

Although we address this issue in the Discussion section, our review was undertaken in 2014; research and practice in some areas may have moved on.

Introduction

Society and healthcare are changing fast.1 An ageing population means increasingly complex patient comorbidity and chronic healthcare and social needs.2 Medical knowledge and ways of treating disease are also rapidly expanding, and there is an increasing requirement to provide a greater proportion of healthcare provision in the community setting, close to patients.1 3 Healthcare delivery must change to meet the needs of patients now and in the future.1 To keep pace with such challenges, high-quality education and training of healthcare workforce is essential.1 4 Furthermore, as patients' lives are at stake, our healthcare workforce needs to be prepared for practice from the very start of their working lives.5–8 But how prepared are today's medical graduates to practice as doctors?

Over the past decade, there has been a steep rise in the number of research papers published on the subject of medical graduates' preparedness for practice for certain clinical domains (eg, safe prescribing).9–13 Given this increase of literature, and that most educators lack the time to find and critically evaluate original articles, review papers play a vital role in our understanding and evidence-based decision-making in medical education. Reviews identify, evaluate and syntheses research findings, making available evidence highly accessible to those who require it.

A systematic review of research examining medical graduates' preparedness for practice was published in 2014.14 Problems identified in the review include graduates' prescribing skills and practical procedures along with their personal issues such as high levels of neuroticism and low levels of confidence impacting negatively on preparedness.14 Poor supervisory interactions were identified as having a negative effect on preparedness with early clinical experience and shadowing opportunities appearing to have a positive impact.14 More recently, Ferguson et al15 reported their systematic review of the literature relating to the educational provision for medical students' preparedness specifically for ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgery in the UK. They found that medical students' training in ENT was extremely short (around 8 days, with some receiving no training at all) and lacked educational value, and final-year medical students and clinicians lacked confidence in their own ability to assess and manage ENT patients.15

However, despite these reviews, evidence of UK graduates' preparedness for practice is still lacking, mainly due to limitations within current studies. For example, Cameron et al14 identified only nine research papers (from 218 potentially relevant articles) published over the past 10 years that examined preparedness to practice across the undergraduate to junior doctor transition. Examining their accompanying online supplementary documents further, it appears that the search strategy was rather narrow: only two databases (MEDLINE and Scopus) were searched using minimal items (only eight terms comprising teaching, education, medical education, medical undergraduate students, medical teaching, transition, clinical clerkship and patient safety). Furthermore, 192 papers were excluded based only on their title with the exclusion criteria used in this process being unclear. This is problematic as not only does the process lack transparency but also it is often difficult to know about the contents of a manuscript based on title alone. The study by Ferguson et al, while being more rigorous and transparent, is limited in scope, focusing on a very small area of preparedness (ENT surgery). What is needed therefore is a study that critically examines the literature around medical graduates' preparedness for practice that has greater transparency and scope than previous studies.

Our research aims to address this gap in the literature by synthesising studies published between 2009 and 2014 that seek to evaluate the success of undergraduate medical education in preparing the next generation of doctors. Given the large amount of literature published since Tomorrow's Doctors 2009,16 the start date of 2009 was selected. Furthermore, within this time frame, notable changes have occurred, partly in response to Tomorrow's Doctors 2009, including the introduction of new curricula and transition interventions such as assistantships (where students are integrated within a clinical team and undertake specified duties under supervision), shadowing (where students observe their specific first job prior to taking it on) and induction.17 Synthesis of this literature is important in order to identify good practice in education and training, identify areas of practice requiring improvement and to set the agenda for future research priorities.

Aim and research questions

The aim of this review is to understand how prepared UK medical graduates are for practice and to inform policy.18 Our specific research questions (RQs) are:

RQ1: How prepared are UK medical graduates for practice?

RQ2: How effective are transitional interventions addressing the final-year medical undergraduates' move into the workplace as a junior doctor?

Method

A rapid review (RR) was conducted using streamlined systematic review methods and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines,19 and registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42013005305).20 As the name implies, an RR is designed to answer a question swiftly and thus addresses urgent demands for synthesised evidence.21 RRs use the rigour of a systematic review, but do so in a shorter time frame. To undertake a high-quality review within these deadlines, RRs are clearly focused.21

Procedure

The time frame for this review comprised an initial 3-month period for the main review (July–August 2013) and a subsequent 6-week period for the update review 10 months later (April–May 2014). The inclusion/exclusion criteria used for the RR were: (1) manuscripts published from 2009 to 2013 (initial review) and 2013 to 2014 (follow-up review); (2) manuscripts published in English; (3) all types of research studies; (4) participant groups: final-year medical students, medical graduates, clinical educators, patients, NHS employers and (5) all outcome measures.

In July 2013, three researchers (LJG, EP and ZJ) searched the following databases: CINAHL, Embase, Educational Resources Information Centre (ERIC), Health Management Information Consortium—Grey literature (HMC), MEDLINE, MEDLINE in Process, PsycINFO, Scopus and Web of Knowledge (WOK). A comprehensive search strategy was developed in Ovid MEDLINE using a combination of medical subject headings and free text terms. The MEDLINE search strategy was modified according to the indexing systems of the other databases.

Across three stages, the strategy combined: Boolean operators, adjacency operators, wildcard symbols, truncation and subject headings and free text search terms. First, terms representing the population were combined using ‘OR’. Second, 54 searches representing variables of preparedness (developed from Tomorrow's Doctors outcomes) were combined using the ‘OR’ Boolean command. Finally, the geographic inclusion areas for the research were added and combined. These three combined ‘OR’ searches were selected and submitted with the ‘AND’ function, and the data were limited by timeframe. To identify research reported in the grey literature, a range of relevant websites were searched. In addition, to identify published resources that have not yet been catalogued in the electronic databases, recent editions of key journals were searched (strategies for each database and websites along with exact numbers of identified manuscripts for each combination are available in online supplement A).

bmjopen-2016-013656suppA.pdf (312.4KB, pdf)

Study selection, quality assessment and data extraction

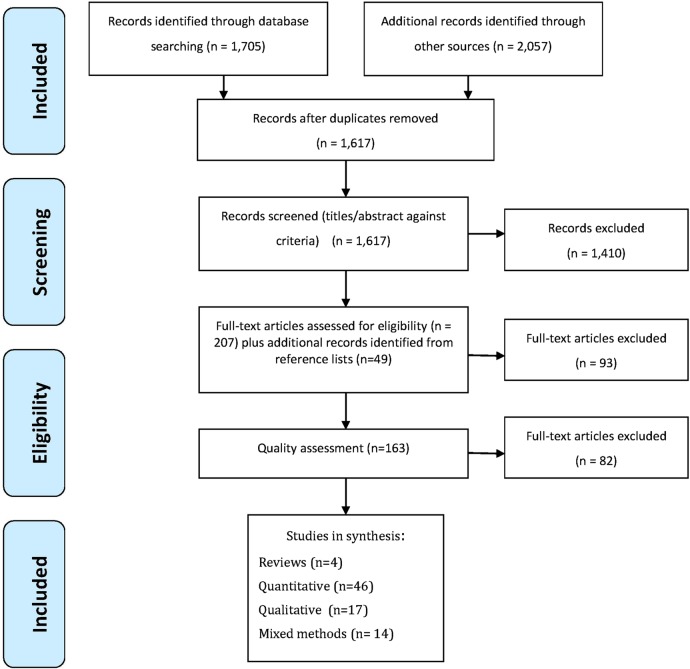

The initial search yielded 3762 results. Figure 1 shows the flow of studies through the review following the PRISMA guidelines.19

Figure 1.

Study selection process 2009–2013.

After screening manuscripts for duplicates and removing manuscripts that did not meet our exclusion and inclusion criteria (box 1), we quality assessed 163 manuscripts using standards specific to their methodology: for quantitative manuscripts, we adapted criteria from the Medical Education Research Study Quality Inventory22 and for qualitative designs, we followed Mays and Pope23 guidance. Both indices were used for mixed methodology studies (see online supplement B for full criteria used). To ensure a cohesive assessment, a second researcher crosschecked 30% of the manuscripts. Following quality assessment, the remaining 81 manuscripts were managed using Atlas.ti software (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH [program], Version 7). These were coded using a framework developed by the researchers (855 codes), and data were extracted for synthesis (see online supplement C).

Box 1. Inclusion criteria.

Participants/population

Types of participants include all graduates from UK Medical Schools.

Intervention(s) and exposure(s)

Interventions relating to undergraduate education in the UK.

Comparator(s)/control

No comparator group.

Context

Medical graduates working as Foundation 1 or 2 trainees in the UK.

Outcome(s)

Primary outcomes: The effectiveness of formal Y5 to F1 transition interventions.

bmjopen-2016-013656suppB.pdf (60.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013656suppC.pdf (87.4KB, pdf)

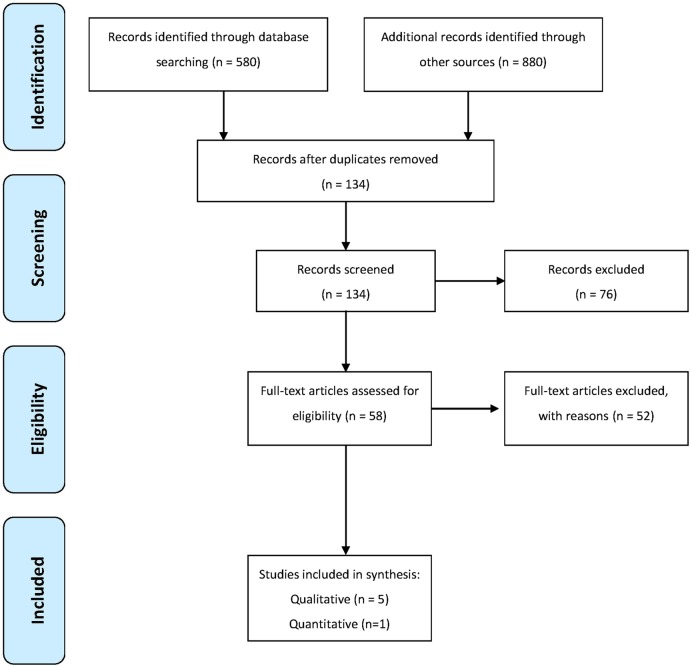

Using exactly the same methodology and process, in May 2014, one of the researchers (LJG) updated the review to include manuscripts published between April 2013 and May 2014 (figure 2). After quality assessment, six manuscripts were added to the original Atlas.ti database resulting in 87 manuscripts being included in this RR overall: n=4 reviews, n=47 quantitative studies, n=22 qualitative studies and n=14 mixed methods studies. As the review comprises a secondary analysis of published data, no ethical approval was needed.

Figure 2.

Study selection process 2013–2014.

Analysis

Synthesis of literature on this topic was challenging since it is diverse (different methodologies used, different contexts studied and different cohorts of graduates), sometimes of low quality and often contradictory. Ideally, study quality influences how much weighting it should be given in drawing conclusions.24 Owing to the variability in study design across the manuscripts, we were unable to use meta-analysis to depict trends in the literature. Instead, we report our narrative synthesis by theme and then map findings from the various studies against the outcomes outlined in the General Medical Council (GMC) outcomes for graduates, grouping them according to whether their data indicate preparedness or not.16 This mapping provides a useful rubric for those involved in curriculum development, offering an at-a-glance understanding of the literature to date for each outcome. Our narrative synthesis presents a second way of thinking about graduates' preparedness by theming the data in terms of the different aspects involved in preparedness for practice. In doing so, we have needed to judge whether data indicate ‘preparedness’, and we have performed that as follows:

Quantitative studies: When Likert scale data are reported as categorical data, at least 20% of the respondents had to indicate preparedness at the highest level in order for us to conclude that this demonstrated ‘preparedness’. This rubric was chosen to avoid an assumption of preparedness in situations where respondents clustered around a midpoint—‘neither prepared nor unprepared’—category. When Likert data were treated as parametric data, the mean level of preparedness is above the midpoint (or equivalent, as some researchers employed a four-point scale).

Qualitative studies: A theme (or subtheme) in which participants verbally reported a high level of preparedness had to be reported for us to conclude that this demonstrated ‘preparedness’.

Mixed methodology studies: The process for quantitative and qualitative studies was amalgamated. There were no studies where different data types were contradicted.

Results

Overview of included studies

A programmatic approach to studying preparedness was lacking: studies varied greatly in terms of design and measures used to determine preparedness. The majority of the studies (66/87, 76%) comprised junior doctors' self-reports of preparedness via questionnaires or interviews that may not reflect actual preparedness. Eighteen of these (18/66, 27%) also collected data from trainers and/or used more than one data-collection method. Trainer reports were in 21/87 (24%) of the studies, via questionnaires (15/21, 71%) or qualitative interviews (6/21, 29%). Of these, only 3 (14%) did not also contain self-report data. Other groups, such as NHS employees or policymakers, were involved in 5/87 (6%) studies, and only 1/87 (1%) involved patients as participants. The number of participants within the studies varied greatly, even within the same methodology. For example, qualitative research studies comprised as few as seven or eight participants from a single location,25 26 to 152 participants across three different locations.27 Questionnaire studies comprised as few as 89 participants from a single location,28 to thousands of participants across multiple locations.29–35

Conceptualising and measuring prearedness for practice differed greatly. Even studies with similar methods of data collection varied substantially. For example, some asked a simple broad question such as “how well did your undergraduate course prepare you for examining patients”36 and provided five categories from ‘unprepared’ to ‘extremely well prepared’. Others provided a general statement such as “my experience at [medical school] prepared me well for the jobs I have undertaken so far”34 37 using five categories from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’ or a scaled response from ‘generally not at all’ to ‘generally very well prepared’. Another approach required junior doctors to rate their preparedness for practice at the point of graduation (a more specific question) against curricula outcomes with a four-point scale from ‘poor’ to ‘very good’.38 One used a five-point scale (‘not at all prepared’ to ‘fully prepared’) for 53 of the outcomes.39 However, that particular study failed to specify all points on their scale, meaning the reader was unable to pinpoint the exact place that ‘unpreparedness’ begins. Not all studies measured confidence or competence. Some tested knowledge (eg, a short test using ‘essential’ and ‘useful’ scenarios) based on topics considered as important for medial graduates.40

Narrative synthesis

To address RQ1, we synthesise the studies identified, discussing our findings in order according to the following themes: medical graduates' preparedness for specific tasks, skills and knowledge; interactional and interpersonal aspects of their preparedness; preparedness for systemic and technological aspects of practice; personal preparedness for practice; and the contribution of personal and situational demographic factors to preparedness variation. We then address RQ2, in the final section: the effectiveness of transitional interventions for final-year medical undergraduates' move to become junior doctors.

Preparedness for specific tasks, skills and knowledge

The area of medical graduates' preparedness for tasks, skills and knowledge received a great deal of research attention between 2009 and 2014: 34/87 (39%) of the studies identified provided information on this aspect. Our synthesis suggests that graduates are reasonably well prepared for history-taking27 36–39 41–43 and performing full physical examinations.36–39 42 However, they are generally unprepared for prescribing safely and legally9–11 13 14 27 35–37 39 41 44–53 clinical reasoning and making diagnoses38–43 54 55 and the early management of patients with emergency conditions.27 28 36 38 39 46 50 51 56 57

The GMC graduate outcomes list 32 specific practical procedures that graduates should be prepared to perform.39 To date, there has been no study (or set of studies) that has examined all 32. Only 14 studies identified graduates' preparedness when mapped across these (table 1). When we consider table 1, this mapping suggests that graduates are prepared for around one-third of the 32 procedures (11/32, 34%). For example, we found unanimous evidence that graduates were prepared for venepuncture;27 39 42 yet for other skills, such as wound suturing36 42 and central venous line insertion,35 58 all the available evidence unanimously suggested that they were unprepared. Table 1 also identifies 11 practical procedures that are absent in the GMC outcomes, yet data suggest that graduates have a level of preparedness for them (eg, central venous line and chest drain insertions).35 58 59

Table 1.

Medical graduates' preparedness for practical procedures

| Practical procedure | Prepared: number and reference(s) |

Unprepared: number and reference(s) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venepuncture* | 4 | Bleakley and Brennan36† Matheson and Matheson42 Illing et al28 Morrow et al40 |

0 | |

| Urinary catheterisation* | 3 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Brown et al42 Matheson and Matheson42 |

3 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Morrow et al40 Illing et al28 |

| Wound suturing* | 0 | 3 | Matheson and Matheson42 Bleakley and Brennan35† Naghavi and Sanati59 |

|

| Administering intramuscular and subcutaneous injections* | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | 3 | Bleakley and Brennan35 † Brown et al42 Matheson and Matheson42 |

| Carry out basic respiratory function tests* | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | 4 | Matheson and Matheson42 Brown et al42 Bleakley and Brennan35† Morrow et al40‡ |

| Blood cultures from peripheral and central sites* | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | 0 | |

| Use of local anaesthetics* | 1 | Brown et al42§ | 2 | Brown et al42§ Bleakley and Brennan35† |

| Making up drugs for parenteral administration* | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | 4 | Brown et al42 Bleakley and Brennan35† Naghavi and Sanati59 Morrow et al40 |

| Perform and interpret ECG* | 2 | Brown et al42§ Bleakley and Brennan35† |

1 | Brown et al42§ |

| Administer oxygen therapy* | 2 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Brown et al42§ |

2 | Brown et al42§ Matheson and Matheson42 |

| Establishing peripheral intravenous access and setting up an infusion* | 3 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Brown et al42§ Matheson and Matheson42 |

2 | Brown et al42§ Bleakley and Brennan35† |

| Nasogastric tube insertion | 2 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Brown et al42§ |

4 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Brown et al42§ Matheson and Matheson42 Morrow et al40 |

| Establish intravenous access for patient with broken veins | 1 | Wijnen-Meijer et al52§ | 1 | Wijnen-Meijer et al52§ |

| Arterial blood sampling | 3 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Brown et al42 Matheson and Matheson42 |

2 | Morrow et al40 Naghavi and Sanati59 |

| Inserting a central venous line | 0 | 2 | Goldacre et al35‡ Naghavi and Sanati59 |

|

| Inserting a chest drain | 0 | 2 | Goldacre et al35 Elsayed et al60 |

|

| Correct use of a nebuliser | 2 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Morrow et al40‡ |

3 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Matheson and Matheson42 Morrow et al40‡ |

| Basic Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) (TD09 16e) | 2 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Matheson and Matheson42 |

1 | Morrow et al40‡ |

| Control of haemorrhage | 0 | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | |

| Total number of different studies | 5 | 9 | ||

*Skills specifically identified in TD09 Appendix A.16

†Different cohorts, newer evidencing greater preparedness.

‡Partial evidence.

§Self-report measures differ from supervisor report.

Blue text, self-report only; Red text, mixed participants/methods; Green text, observational data; Black text, trainer report only.

Data are sometimes inconclusive in terms of preparedness with similar numbers of studies supporting on each side (table 1). These disparities, to an extent, are due to different participant groups reporting different preparedness levels (eg, educational supervisors' reports are generally lower than trainees' self-reports)36 42 or to studies evaluating different curricula.36 Most of the data suggesting preparedness came from a limited study range using self-reports, whereas the reports of unpreparedness originate from a wider range of studies/methodologies.

Preparedness for interactional and interpersonal aspects of practice

A small proportion of studies (12/87, 14%) researched preparedness at an interactional and interpersonal level, and the results were mixed. For almost all of the interactional and interpersonal aspects of practice domains identified by the GMC outcomes, there are contradictory results. Where there are data, by purely adding up the number of studies we might think that graduates are prepared for communication with colleagues and patients.27 36 37 39 41 42 Although there are few studies of preparedness for multidisciplinary team-working, the evidence is relatively robust and indicates unpreparedness of graduates: thus, two of the three manuscripts suggesting problems in this area had multidisciplinary team-working as the sole focus of their work.60 61 Both concluded that medical graduates have preparedness problems. This contrasts with scant data suggesting trainees' preparedness based on simple questions in two large-scale studies focusing on the wider issue of preparedness.42 51

For breaking bad news, equal number of studies provide evidence for preparedness36 42 51 and unpreparedness.27 51 62 In terms of preparedness, the evidence comprises three questionnaire studies containing a single self-report. However, of these, one also found supervisor reports differed considerably,51 suggesting serious concerns. Furthermore, two other studies highlighted the breaking of bad news as complex and considered by trainees to be more distressing than other upsetting duties, giving potential for them getting quickly out of their depth.27 62 Finally, only three papers reported on handover preparedness for trainees,63–65 all suggesting trainees' unpreparedness.

Preparedness for systemic and technological aspects of practice

Preparedness for systemic and technological aspects of practice is generally an under researched area (13/87, 15%), again providing very mixed results. For example, the same studies found evidence that graduates have knowledge of, and are able to use, audit to improve patient care, but they also lack such knowledge.36 37 41 This contradiction can be understood in terms of there being different cohorts under study (eg, self-reports from the ‘old’ curriculum suggesting unprepared and the ‘new’ suggesting prepared)36 and self-report/other-report differences (suggesting prepared and unprepared, respectively).37 41

Other aspects within this theme suggest a clearer picture. For example, three studies provided self-reported and patient-reported data suggesting medical graduates' unpreparedness for reporting and dealing with error and safety incidents.36 52 66 Studies also strongly suggest that graduates are ill prepared for understanding how the clinical environment works:13 27 38 47 67 junior doctors and their educational supervisors thought that familiarity with the ward environment was an important missing component of transition, with feelings of preparedness being contingent on understanding ward culture and practices.

Personal preparedness for practice

Personal preparedness refers to individual aspects of preparedness. Only 11/87 (13%) of the manuscripts reported data regarding trainees' personal preparedness for practice. As with earlier sections, the evidence is complex. Medical graduates often have problems with time management,27 36 37 60 68 but seem to understand their own limitations36 37 41 42 with inconclusive data on graduates' abilities to identify and organise their learning needs and reflective practice.37 41 42 For this latter aspect, perhaps graduates from older curricula are less well prepared than those learning in a more contemporary way.37 Finally, there is reasonably strong evidence (multicentre studies and knowledge measures) that graduates have problems of preparedness around ethical and legal issues,39 including for complex ethical situations (eg, caring for dying patients)62 and understanding mental health law.69

The impact of personal and situational demographic factors on preparedness variation

This issue of whether personal or situational demographic factors affected preparedness for practice was not included in many of the manuscripts identified in this review. In terms of personal demographics, only ethnicity, gender and personality ‘traits’ are addressed in the studies found. In terms of ethnicity, an extremely large cohort study (with 11 610 trainees 1-year postgraduation and 8427 3-years postgraduation) found ethnicity to be a statistically significant predictor of general feelings of preparedness in both cohorts, but gender only at the 3-year postgraduate time: white doctors reporting higher levels than non-white doctors and men higher than women.35 Furthermore, another study using the same measurement also found no significant effect of gender on graduation.70 From this we might conclude that any effect of gender in self-reported preparedness might well be due to an interaction between gender and the workplace environment. One further personal factor that has been demonstrated to have an effect on levels of preparedness is personality ‘traits’: with positive correlations between ‘agreeableness’ and ‘conscientiousness’ and preparedness, and a negative correlation between ‘neuroticism’ and preparedness.70 However, although statistically significant, effect sizes are very low (all well below r=0.20), suggesting these findings might have limited practical use.

In terms of situational factors, this was generally researched using self-reported data. Evidence suggests that the following factors influence higher self-ratings of preparedness: medical school,14 34–36 39 67 graduates from more recent cohorts,27 34 35 37 graduate-entry students,35 70 shadowing and other attachments,70 problem-based learning courses,27 70 UK-trained versus non-UK-trained graduates working in the UK,32 60 graduates with an intercalated degree35 and experience since starting work.70 Furthermore, there is some evidence that suggests that school is not a factor.14 27 Looking at the studies further we can see that medical school does not appear to make a big difference for self-reported preparedness when the broad question “Experience at medical school prepared me well for the jobs I have undertaken so far” is asked. However, when the more nuanced question of ‘preparedness for what?’ is asked, differences between schools for certain domains of activities are revealed.36 39 As such, research examining the detail tends to provide more practical data for us to develop future curricula.

Effectiveness of final-year undergraduate to junior doctor transition interventions

Few of the papers (15/87; 17%) in this review contributed to our understandings of the efficacy of assistantships, induction and shadowing.

Assistantships

Assistantships have been defined as a period of hands-on learning enabling medical students to become fully integrated in a clinical team to practise their clinical skills and to take on some responsibilities under supervision.17 Only one paper reported data on assistantships,44 which considered them beneficial in relieving anxieties and providing invaluable opportunities for incorporating students into multidisciplinary teams. Although not the focus of their research, authors of other papers appeared hopeful that assistantships could help with many preparedness problems.10 14 35 39 46 71

Shadowing

Since early 2012, shadowing has comprised a compulsory 4-day paid period immediately prior to becoming a junior doctor in which they are able to become familiar with future working environments and expectations. It should provide protected time for graduates to develop relationships with their clinical and educational supervisors alongside their future colleagues.17 Prior to this time, shadowing was variable. A total of 11/87 (13%) of manuscripts in this review reported relevant data on shadowing:8 10 12 13 27 30 42 46 64 70–72 of which, 8/11 (73%) were dated prior to the compulsory change in 20128 10 30 42 63 70–75 and 9/11 (82%) presented self-reported data (all except27 46). For the pre-2012 studies, what was meant by the term ‘shadowing’ was not defined. Furthermore, not all participants in the studies experienced shadowing: in one study, it comprised a compulsory component to the course being studied;46 in others, there were reports of ‘some’ shadowing, a lack of shadowing opportunities10 30 70 71 and shadowing of variable durations: 2 days,64 1–2 weeks8 and 4+ weeks.8

Generally, these data suggest that shadowing is considered an efficacious method for developing graduates' preparedness. However, while some shadowing is considered better than none,44 70 it should be reflective of the new post,42 and reinforced with related teaching.70 Finally, a prolonged shadowing period can be ineffectual due to repetitive tasks undertaken with little opportunity for new learning.10

Induction

Induction is a mandatory process whereby a medical graduate is introduced to the junior doctors' work environment and employment policies by the human resources team.17 Despite a clear definition, researchers and participants sometimes confused shadowing with induction.8 67 Moreover, induction varies: it can comprise face-to-face meetings, information packs and online courses.8 12 67 The majority of studies in this section comprised self-report data (only one exception),64 often being large-scale, across multiple sites and suggesting a high level of efficacy for the process.10 12 29 30 33 34 64 67 However, despite this, the inconsistent nature of induction across trusts or wards is problematic.8 12 30 34 This includes problems of insufficient induction stemming from timetable difficulties and staff shortages, with researchers suggesting a possible correlation between feeling unprepared and inadequate (or no) induction breeding errors alongside feelings of unpreparedness, disorganisation, frustration and anxiety.8 12 34

Mapping preparedness to graduate outcomes

We now present our findings by mapping the included papers to the graduate outcomes as represented in the GMC outcomes for graduates document (table 2).16 This comprises three main subheadings for outcomes: doctor as scientist and scholar, as practitioner and as professional. Given that we have already discussed specific preparedness issues by topic, we now highlight the amount of evidence present for each of these aspects of practice. As we can see from table 2, only five studies presented data relating to the doctor as scientist and scholar outcomes,36–38 42 73 and the vast majority of studies considered the doctor as practitioner and professional outcomes. Data mainly suggest that graduates are prepared for the scientist and scholar aspect.37

Table 2.

Manuscripts suggesting preparedness versus unpreparedness of medical graduates from 2009 to 2014 mapped against the outcomes for graduates

| Specific outcome | Prepared: number and reference(s) |

Unprepared: number and reference(s) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor as scientist and scholar (8–12) | ||||

| Knowledge of anatomy (TD09 8*) | 0 | 1 | Dickson et al73 | |

| Understanding disease processes (TD09 8e*) | 2 | Matheson and Matheson42 Watmough et al38† |

1 | Watmough et al37† |

| Apply scientific principles, method and knowledge to medical practice and research (TD09 9*) | 1 | Tallentire et al39 | 0 | |

| Knowledge of clinical, behavioural and social sciences for medicine (TD09 9* and 10*) | 2 | Matheson and Matheson42 Tallentire et al39 |

0 | |

| Basic nutritional care/knowledge (TD09 11h) | 2 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Matheson and Matheson42 |

0 | |

| Total number of different studies | 4 | 2 | ||

| Doctor as practitioner (13–19) | ||||

| Taking a history (TD09 13a) | 8 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Brown et al42 Estcourt et al43 Illing et al28 Matheson and Matheson42 Morrow et al40 Tallentire et al39 Watmough et al37 |

0 | |

| Communicate sensitively, clearly and effectively with patients and relatives (TD09 13b*) | 2 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Matheson and Matheson42 |

0 | |

| Performing a full physical examination (TD09 13c) | 5 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Matheson and Matheson42 Morrow et al40 Tallentire et al39 Watmough et al37 |

0 | |

| Perform a mental-state examination (TD09 13d) | 2 | Matheson and Matheson42 Watmough et al37 |

1 | Gordon56 |

| Hold conversation with patient and family to explain a mistake (TD09 13g*) | 1 | Wijnen-Meijer et al52‡ | 1 | Wijnen-Meijer et al52‡ |

| Using evidence and guidelines for patient care (including developing critical thinking) (TD09 14a*) | 1 | Watmough et al37† | 4 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Matheson and Matheson42 Tallentire et al39 Watmough et al37† |

| Recognising the social and emotional factors in illness and treatment (TD09 14a*) | 3 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Matheson and Matheson42 Watmough et al37† |

1 | Watmough et al37† |

| Clinical reasoning and making a diagnosis (TD09 14b,f*) | 3 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Laws et al76 Watmough et al37 |

8 | Atrey et al40 Brown et al42 Davis and MacLullich54 Estcourt et al43 George et al55 Matheson and Matheson42 Morrow et al40 Tallentire et al39 |

| To draw up an examination plan for a new patient at the outpatient department (TD09 14c*) | 1 | Wijnen-Meijer et al52‡ | 1 | Wijnen-Meijer et al52‡ |

| Selecting appropriate investigations and interpreting the results (TD09 14d*) | 2 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Watmough et al37 |

1 | Matheson and Matheson42 |

| Protecting patients' rights (TD09 14g*) | 1 | Matheson and Matheson42 | 0 | |

| Planning discharge for patients (TD09 14g*) | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | 0 | |

| Identifying signs of abuse (TD09 14i) | 0 | 1 | Estcourt et al43 | |

| End of life care (TD09 14j) | 0 | 2 | Gibbins et al75 Linklater62 Bowden et al74 |

|

| Writing out part A of a cremation form (TD09 14j*) | 0 | 1 | Morrow et al40 | |

| Communicate effectively in multidisciplinary/interdisciplinary team (TD09 15*) | 2 | Matheson and Matheson42 Wijnen-Meijer et al52‡ |

3 | Lewis and Tully61 McGettigan et al60 Wijnen-Meijer et al52‡ |

| Communicate effectively in a medical context (TD09 15*) | 1 | Tallentire et al39 | 0 | |

| Communicating effectively with colleagues (TD09 15a*) | 4 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Illing et al28 Matheson and Matheson42 Wijnen-Meijer et al52 |

1 | Watmough et al37 |

| Breaking bad news to patients and relatives (TD09 15d) | 3 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Matheson and Matheson42 Wijnen-Meijer et al52‡ |

4 | Linklater et al62 Illing et al28 Wijnen-Meijer et al52‡ Bowden et al74 |

| Dealing with difficult or violent patients (TD09 15e) | 0 | 2 | Matheson and Matheson42 Morrow et al40 |

|

| Treating acutely ill patients (TD09 item 16) | 3 | Carling et al26 Burns65 Tallentire et al77 |

2 | Illing et al28 Watmough et al37 |

| Diagnose and manage acute medical emergencies (TD09 16b) | 3 | Carling et al26 Hobson28† Tallentire et al39†‡ |

9 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Gordon56 Hobson28 † Illing et al28 Kavanagh et al47 Mastoridis et al57 Morrow et al40 Tallentire et al39 51 77†‡ Wijnen-Meijer et al52 |

| Explain drug prescription choice to a pharmacist (TD09 17b) | 1 | Wijnen-Meijer et al52‡ | 1 | Wijnen-Meijer et al52‡ |

| Prescribing safely (TD09 17c) | 5 | Dornan et al10§ Matheson and Matheson42 Morrow et al40 Tallentire et al39‡ Watmough et al37† |

23 | Ahmed et al52 Brown et al42 Bertels et al9 Bleakley and Brennan35† Brennan et al44 Dornan et al10§ Franklin et al46 Goldacre et al35 Harding et al11 Illing et al27 Kavanagh et al47 Kilminster et al48 Lewis and Tully61 Mattick et al13 Morrow et al40 Ross et al78 Ross et al49 Rothwell et al14 Ryan et al50 Seden et al54 Tallentire et al51 Watmough et al37† Wijnen-Meijer et al52 |

| Calculate drug dosage and record outcome (TD09 17d) | 0 | 5 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Dornan et al10 Matheson and Matheson42 Mattick et al13 Morrow et al40 |

|

| Apply knowledge of alternative and complementary therapies and how these may affect other treatments (TD09 17h) | 0 | 1 | Morrow et al40 | |

| Keeping an accurate and relevant medical record (TD09 19a) | 2 | Brown et al42 Matheson and Matheson42 |

1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† |

| Maintaining confidentiality (TD2009 19c*) | 1 | Matheson and Matheson42 | 0 | |

| Using informatics as a tool in medical practice (TD09 19e) | 2 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Watmough et al37† |

2 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Watmough et al37† |

| Total number of different studies | 15 | 37 | ||

| Doctor as professional (20–23) | ||||

| Overall patient-centred practice and humane care/recognises all aspects of care (TD09 20b*) | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | 1 | McGettigan et al60 |

| Acting in a professional manner (with honesty and probity) (TD09 20c*) | 2 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Matheson and Matheson42 |

0 | |

| Providing appropriate care for people of different cultures (TD09 20d*) | 2 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Matheson and Matheson42 |

1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† |

| Knowledge of key mental health legislation (TD09 20f*) | 1 | Wadoo et al69 | 0 | |

| Understanding ethical and legal issues (such as confidentiality and consent) (TD09 20f*) | 6 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Brown et al42 Matheson and Matheson42 Preston-Shoot and McKimm78 Tallentire et al39 Watmough et al37† |

4 | Linklater et al61 Morrow et al40 Wadoo et al68 Watmough et al37† |

| Sickness certification (TD09 20g*) | 0 | 1 | Walters et al79 | |

| Identifying and organising own learning needs, reflective practice (TD09 21b*) | 3 | Brown et al42 Matheson and Matheson42 Watmough et al37† |

3 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Tallentire et al39 Watmough et al37† |

| Time management (TD09 21d*) | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | 4 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Illing et al28 McGettigan et al60 Watmough et al37 |

| Asking for help (TD09 21e*) | 2 | Brown et al42 Matheson and Matheson42 |

0 | |

| Being aware of their limitations (TD09 21e*) | 4 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Brown et al42 Matheson and Matheson42 Watmough et al37 |

1 | †Watmough et al37 |

| Undertaking a teaching role (TD09 21f*) | 2 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Wijnen-Meijer et al52‡ |

2 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Wijnen-Meijer et al52‡ |

| Working effectively in a team (TD09 22*) | 6 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Brown et al42 Illing et al28 Matheson and Matheson42 Morrow et al40 Watmough et al37† |

1 | Watmough et al37† |

| Understanding roles of other healthcare professionals (TD09 22a*) | 1 | Watmough et al37† | 1 | Watmough et al37† |

| Ensuring and promoting patient safety (TD09 23a*, d*) | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | 1 | McGettigan et al60 |

| Coping with uncertainty (TD09 23b) | 0 | 2 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Watmough et al37 |

|

| Using knowledge of the structures and functions of the NHS in practice (TD09 23c*) | 0 | 1 | Morrow et al40 | |

| Reporting and dealing with error and safety incidents (TD09 23d*) | 0 | 3 | Ahmed et al53 Bleakley and Brennan35† Cresswell et al67 |

|

| Clinical governance (TD09 23d*) | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† |

| Knowledge/using audit to improve patient care (TD09 23e*) | 3 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Brown et al42‡ Watmough et al37† |

3 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Brown et al42 ‡ Watmough et al37† |

| Dealing appropriately, effectively, and in patients' interests with problems in the performance, conduct or health of colleagues (TD09 23d*, i*) | 0 | 1 | Matheson and Matheson42 | |

| Reducing the risk of cross-infection (TD09 23h) | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | 0 | |

| Managing their health, including stress (TD09 23i*) | 0 | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | |

| Total number of different studies | 10 | 14 | ||

| Items not directly mapped to outcomes for graduates | ||||

| To give a presentation at the clinical team meeting after a night shift | 1 | Wijnen-Meijer et al52 | ||

| Write letter of referral to colleague | 1 | Wijnen-Meijer et al52‡ | 1 | Wijnen-Meijer et al52‡ |

| Able to participate in effective handover | 0 | 3 | Burns65 Cleland et al63 Raduma-Tomàs et al66 |

|

| Understanding how the clinical environment works (not an outcome for graduates but appears in TD09 106, p. 54) | 1 | Matheson and Matheson42 | 5 | Illing et al28 Kilminster et al48 Mattick et al13 Tallentire et al39 Van Hamel and Jenner67 |

| Understanding the relationship between primary/social care and hospital care | 0 | 2 | Bleakley and Brennan35† Watmough et al37 |

|

| Knowledge and understanding of rehabilitation and care within institutions and the community | 1 | Matheson and Matheson42‡ | 1 | Matheson and Matheson42‡ |

| Understanding the purpose and practice of appraisal | 0 | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | |

| Use information and technology effectively in medical context | 1 | Tallentire et al39 | ||

| Organisational decision-making | 0 | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | |

| Applying clinical pharmacology and therapeutics to prescribing | 0 | 2 | Harding et al11 Mattick et al13 |

|

| To ask a representative critical questions about the pharmaceutical product | 0 | 1 | Wijnen-Meijer et al52 | |

| Preoperative assessment of patients | 0 | 1 | Morrow et al40 | |

| Taking part in advanced life support | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† |

| Functioning safely in an acute ‘take’ team | 0 | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | |

| Educating patients (health and public health) promotion | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | 0 | |

| Maintaining good quality care | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | 0 | |

| Carrying out a literature search | 1 | Watmough et al37† | 1 | Watmough et al37† |

| Skills of close observation | 0 | 1 | Bleakley and Brennan35† | |

| Total number of different studies | 5 | 14 | ||

*Partially relevant to the specified outcome.

†Different cohorts, newer evidencing greater preparedness.

‡Trainees suggest preparedness where supervisors do not.

§Self-reports suggest prepared and observational data suggest unprepared.

Blue text, self-report only; Red text, mixed participants/methods; Black text, trainer report only.

Within the doctor as practitioner outcomes, some aspects (eg, drugs and prescribing) receive more attention than others (eg, keeping accurate medical records). Furthermore, many more studies suggest that graduates are unprepared9–11 13 14 27 28 35–57 60–62 74–76 80 than those suggesting they are prepared.10 25 27 28 36–39 41–43 50 51 64 81 Most studies providing evidence of graduates' preparedness also provide evidence of graduates' unpreparedness (only four do not); such studies include different cohorts of graduates (eg, new vs old curricula) or differing perspectives (eg, trainee vs trainer).25 41 64 81 Similarly, the studies mapping to the doctor as professional show more contributing evidence to suggest graduates unprepared27 36–39 41 42 51 52 60 62 66 69 79 than prepared,27 36–39 41 42 51 69 78 with only one study contributing data purely suggesting graduates are prepared.78

Finally, in the last section of table 2, we set out where studies in our review provide data on graduates' relative preparedness for aspects of their work that do not feature in the outcomes for graduates. For example, understanding how the clinical environment works and clinical handover (sometimes called handoff) do not appear in the outcomes. Once again the pattern of preparedness shows far more studies, providing evidence that graduates are unprepared11 13 27 36–39 42 47 51 63–65 67 than those providing evidence they are prepared,36–38 42 51 with no studies purely contributing to the latter.

Discussion

Through our RR, we have assimilated the literature published after the introduction of the Tomorrow's Doctors 2009 outcomes to investigate questions around UK graduates' preparedness to practise as junior doctors. The majority of studies comprised self-reports, although over one quarter also included other-reports (eg, trainers and policymakers). The concept of preparedness was variously defined and measured making quantitative synthesis problematic. We therefore presented a qualitative synthesis of the studies. Many studies provided evidence of preparedness and unpreparedness of graduates, although overall, a greater number of studies in our review provided data to suggest that graduates are more unprepared for practice than they are prepared.

Studies in our review suggested that junior doctors appear well prepared for history taking, physical examinations, venepuncture, audit and understanding their own limitations. Studies were inconclusive regarding levels of preparedness for communication with colleagues and patients: problem areas seem to include multidisciplinary team-working, handovers, breaking bad news to patients, learning needs and reflective practice. There is also much evidence to suggest that graduates are underprepared for safe and legal prescribing, and some evidence for clinical reasoning and diagnoses, early management of emergency patients, wound suturing, central venous line and chest drain insertion, dealing with safety and error reporting, ethical and legal issues and understanding how the clinical environment works. However, it must be noted that some of these aspects do not fall within the GMC outcomes for graduates (eg, central venous line and chest drain insertion), and this must be taken into account when assessing overall preparedness.

Clearly, the issue of preparedness is not clear-cut. One reason for this is that we identified clear contradictions in the literature regarding the level of self-reported preparedness compared with expert assessment of their skills whereby graduates rate themselves as more prepared than their seniors rate them.36 38 41 51 For example, this discrepancy was identified in assessing communication skills: while graduates rated themselves as prepared for breaking bad news and communicating with a multidisciplinary team, their experienced senior colleagues reported that this was not the case.51 Such an overestimation of preparedness could be an example of illusory superiority.82 This increased perception could be a protective mechanism, whereby graduates do not want to acknowledge that they are less than well prepared as a way of maintaining positivity.83 84 Alternatively, this could be due to a discrepancy in experience: seniors viewing everyone below their own level as being less competent; therefore, graduates are deemed unprepared for the reality of everyday work as known by their seniors. As graduates can only assess their preparedness against their own experiences, they are therefore unlikely to be aware of the nuances of preparedness that only comes with experience: the so-called unknown unknowns.85 Taken together, these two perceptions of what comprises preparedness can explain the apparent contradictions found in the literature.

In addition to differing perspectives on levels of preparedness, we identified numerous studies reporting differences in preparedness due to personal or situational demographics that also contribute to the lack of clarity around graduates' preparedness for specific factors (ie, why some studies suggest that graduates are prepared and unprepared). Regarding personal factors, we found weak evidence to suggest that ethnicity, gender and personality ‘traits’ impact on self-reported levels of preparedness.35 70 The evidence regarding the impact of situational factors, however, is stronger. Following the extensive transformation of medical education curricula in the UK since the 1990s, numerous studies are beginning to shed light onto how changes might affect levels of preparedness: higher levels have been recorded for graduates of ‘new’ (vs ‘traditional’) curricula, graduate-entry students, graduates of problem-based learning courses and those who have intercalated.14 27 32 34 35 37 60 70 However, this issue of curricula brings forth a concern around the issue of publication bias—since researchers might be loathe to publish null or even negative results on this issue; particularly, if they have been through a great deal of organisational strife to achieve changes in their curricula.86 The evidence is mixed, however, in terms of whether different medical schools in the UK graduate more prepared students, generalised self-reports of preparedness by school are consistent over time and some schools fare better than others across different activity domains.36 39

Our findings around preparedness are often contradictory. However, we found areas of preparedness where the evidence was strong and we now consider those areas where conclusions can be drawn with some confidence. For example, we have strong evidence to suggest that graduates are unprepared in their understanding of the issues around prescribing and emergency care (including their clinical reasoning skills).9–11 13 14 27 36–38 39 41 44–53 77 Not only have there been numerous studies in these areas, all pointing to similar issues, but also studies have utilised more robust methodologies, including having multiple sources of data across more than one location.10 12 14 38 42 49 51 From studies such as these, researchers have been able to unpick the various individual and contextual factors related to the issue of unpreparedness: for example, in terms of prescribing, preparedness is no longer considered as an individual ‘skill’ in isolation, but rather has been re-framed to include the consideration of a wider range of interpersonal, cultural and environmental aspects that impact on medical graduates' abilities to prescribe safely.14

Our second RQ focused on the different types of transitional interventions that might affect graduates' preparedness, namely assistantships, shadowing and induction. We found very little evidence with which to draw any firm conclusions around the efficacy of assistantships due to the paucity of data, although some evidence suggests that they might alleviate anxieties and provide opportunities for team-working.44 More recent research (outside the scope of this RR) focusing on student assistantships suggests how they might facilitate transitions into practice (practically and psychologically).87–91 Additionally, assistantships in placements aligned and misaligned with their future junior doctor post sheds further light on these findings, suggesting that alignment with students' first post can enhance confidence, team belonging and workplace acclimatisation.6 Thus, aligning final student placements with their first post as a junior doctor is effectively providing them with an extended shadowing period. This latter finding therefore builds on the evidence in our review around the efficacious effect of the trainee shadowing their first post so long as appropriate teaching is in place.69 Finally, studies examining the induction period provide further evidence of the importance of the organisational factors involved in graduates' preparedness: when induction is insufficient (either inadequate or absent), graduates can feel unprepared, disorganised, frustrated and anxious.8 12 34 Taken together, this suggests that carefully designed and implemented transitional interventions, on the undergraduate and postgraduate sides, are an essential component to junior doctors' well-being and patient safety. Indeed, preliminary data from two studies (n=12 and n=33) around the benefits and challenges of students' proactive participation in prescribing in the workplace through the novel intervention of pre-prescribing—in which students make prescribing judgements under supervision—suggest a potential way forward for this specific aspect of preparedness.92 93

Study limitations and strengths

This study has a number of limitations. Although our methodology has enabled us to quickly assimilate the literature to provide an overview of the current climate of graduates' preparedness, the broad scope of preparedness, wide variability in conceptualising preparedness for practice, diverse study designs and quality led to difficulties in ascertaining firm conclusions as to whether or not graduates are generally prepared for practice. This is not a black and white issue: for example, while the list of procedures was current when the study was planned, there are some procedures that junior doctors are no longer expected to undertake and the context of healthcare (eg, team structure and digital systems) is changing fast, so preparedness for practice will be an ever-changing construct.

Additionally, many studies collected data immediately after graduation, so focused purely on short-term aspects of preparedness: preparedness for graduates' first days as a junior doctor. Many papers failed to state when the data were collected, for example, how far into practice, as those first few weeks are a steep learning curve and data might change substantially 1 week in, to 1 month in, to 1 year in. In contrast, Goldacre et al35 undertook the largest scale longitudinal study in the UK to date (examining graduate cohorts from 1999, 2000, 2002 and 2005), with some being followed 1 or 3 years post qualification.35 Many participants in the earlier cohorts were asked the simple broad-brush question “Experience at medical school prepared me well for the jobs I have undertaken so far” requiring a 1–5 Likert scale response. Additional items in latter years only included questions on clinical knowledge, procedures, administrative tasks, interpersonal skills and physical, emotional and/or mental demands; again requiring simple Likert scale responses. However, not only are the data reported in this study now over 10 years, it measured very few aspects of preparedness highlighted in our review. Owing to the paucity of longitudinal studies, there are currently no data following graduates throughout their career and measuring aspects of their preparedness for lifelong learning and adaptation to their roles as doctors.

The majority of manuscripts did not define the concept of preparedness, but tended to focus on knowledge and skills required immediately on graduation rather than researching longer term preparedness for becoming a doctor, or behaviours and patient outcomes. The effect of this is to downplay the important remit of medical schools in preparing graduates for lifelong learning and development. There are also important issues to consider with regards all published literature, such as the influence of publication bias.

Another limitation to our study is that this review was undertaken in 2014; it is therefore likely that research and practice in some areas may have moved on. For example, recent research around the newly developed assistantship programme that was somewhat lacking pre-2014 has begun to unpack issues to do with how they might facilitate transitions into practice (practically and psychologically) and the relative efficacy of different assistantship models (eg, benefits and challenges in when aligning/misaligning assistantship experiences with subsequent junior doctor posts).6 88–92 Such recent intervention strategies are not well served in our review. Although this review might benefit from being updated, we are of the opinion that a full systematic review update will not necessarily generate a great deal of additional papers: the last update we did (taking 3 weeks) looking at a 2-year period and reported fully here, only led to six additional papers being found. As such, we do not believe that another update so soon will greatly alter the validity of the findings reported here.

Finally, we recognise that this RR is limited by stringent time constraints. However, due to the concentrated effort of the research team, we were able to undertake the same rigorous steps as other systematic reviews. We therefore believe that our findings are credible. Indeed, research comparing RR and systematic review methodologies suggests that, despite the differences between them, their essential conclusions do not differ extensively.94 As such, we believe that our research has a number of strengths, including the robustness of our search strategy and methodological rigour. This has enabled us to identify a greater range of relevant manuscripts than previous studies examining the issue of UK graduates' preparedness,14 leading to a synthesis of the current literature on medical graduates' preparedness to practise in the UK that we hope provides policymakers and educational developers with a strong overview of the current climate of preparedness.

Recommendations for future practice and research

Based on our analysis of the studies undertaken so far, we make methodological and topic-focused recommendations. In terms of topic-focused recommendations, the data are clear that graduates are unprepared in certain areas, for example, prescribing. For these areas, we need educational interventions in order to address them and then further research. For example, the prescribing safety assessment (PSA) was piloted in the UK in 2013, and by 2014, most medical students graduating in the UK sat it for the first time. We would therefore expect to see research arising from the PSA implementation in the near future given that success in the PSA is becoming a requirement for completion of the Foundation 1 year.

It is also easy to see from our review where further research is needed (eg, where data are unclear). For the latter, future research should adopt a more programmatic and rigorous approach to understanding the issues at hand and clear definitions of preparedness. Self-report data alone are insufficient and multiple stakeholder perspectives are recommended. Furthermore, we suggest that future research employs multisite and longitudinal research designs using a range of research methods (eg, observational, questionnaire and action research) to understand the concept and process of preparedness alongside the variety of individual, cultural and organisational issues that might impact on this. In short, a more joined-up, systematic, approach to understanding the educational requirements for junior doctors, and how to achieve this, is required.

Conclusion

Graduates appear to be well prepared for some of the basic clinical procedures (eg, venepuncture) and other aspects of clinical practice (eg, history taking) that will be required of them as new graduates. Through this research we have identified some areas in which graduates are clearly underprepared and where educational and support interventions will be required, either during medical school and/or in the clinical environment in which the junior doctor will work. Some interventions have already been introduced to address these areas (eg, the PSA for fifth-year medical students), and future research should explore the impact they have made. Through this research, we have also identified other areas in which the degree of preparedness of graduates is unclear and these require further research. We have also identified ways in which the quality of research in this area can be improved and so we believe that researchers interested in exploring this important topic should be very well positioned to make a significant research contribution.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Charlotte Rees, Dr Gerry Gormley, Dr Judith Cole, Dr Kathrin Kaufhold, Dr Narcie Kelly, Dr Grit Scheffler, Mr Christopher Jefferies and Ms Camille Kostov for their work on the wider study and comments on the original report to the funders.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Lynn V Monrouxe @LynnMonrouxe and Mala Mann at @SysReviews

Contributors: LVM, MM, AB and KM conceived the idea and designed the study. LG, EP and ZJ developed the search strategy for the study and undertook the search and screening process at Time 1 under the supervision of MM, LVM and AB. LG undertook the search and screening process at Time 2 under the supervision of LVM. All authors developed the thematic coding and subsequent data analysis. LVM, LG and KM undertook the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript and all authors approved the final version.

Funding: This research was commissioned and funded by the General Medical Council who gave feedback on clarity and approved the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The raw data for this research comprise data available to others through peer-reviewed journals, some of which is copyright, we therefore are not at liberty to share.

References

- 1.Royal College of General Practitioners. The 2022 GP: a vision for general practice in the future NHS. London: Royal College of General Practitioners, 2013. http://wwwrcgporguk/campaign-home/~/media/files/policy/a-z-policy/the-2022-gp-a-vision-for-general-practice-in-the-future-nhsashx. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd CM, Fortin M. Future of multimorbidity research: how should understanding of multimorbidity inform health system design? Public Health Rev 2010;33:451–74. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q 2005;83:457–502. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grosios K, Gahan PB, Burbidge J. Overview of healthcare in the UK. EPMA J 2010;1:529–34. 10.1007/s13167-010-0050-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jen MH, Bottle A, Majeed A et al. Early in-hospital mortality following trainee doctors’ first day at work. PLoS ONE 2009;4:e7103 10.1371/journal.pone.0007103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones OM, Okeke C, Bullock A et al. ‘He's going to be a doctor in August’: a narrative interview study of medical students’ and their educators’ experiences of aligned and misaligned assistantships. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011817 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma V, Proctor I, Winstanley A. Mortality in a teaching hospital during junior doctor changeover: a regional and national comparison. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2013;74:167–9. 10.12968/hmed.2013.74.3.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaughan L, McAlister G, Bell D. ‘August is always a nightmare’: results of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh and Society of Acute Medicine August transition survey. Clin Med 2011;11:322–6. 10.7861/clinmedicine.11-4-322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertels J, Almoudaris AM, Cortoos PJ et al. Feedback on prescribing errors to junior doctors: exploring views, problems and preferred methods. Int J Clin Pharm 2013;35:332–8. 10.1007/s11096-013-9759-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dornan T, Ashcroft D, Heathfield H et al. An in-depth investigation into causes of prescribing errors by foundation trainees in relation to their medical education. QUIP study. General Medical Council, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harding S, Britten N, Bristow D. The performance of junior doctors in applying clinical pharmacology knowledge and prescribing skills to standardized clinical cases. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2010;69:598–606. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03645.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mattick K, Kelly N, Rees C. A window into the lives of junior doctors: narrative interviews exploring antimicrobial prescribing experiences. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014;69:2274–83. 10.1093/jac/dku093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothwell C, Burford B, Morrison J et al. Junior doctors prescribing: enhancing their learning in practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012;73:194–202. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04061.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cameron A, Millar J, Szmidt N et al. Can new doctors be prepared for practice? A review. Clin Teach 2014;11:188–92. 10.1111/tct.12127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferguson GR, Bacila IA, Swamy M. Does current provision of undergraduate education prepare UK medical students in ENT? A systematic literature review. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010054 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.General Medical Council. Tomorrow's Doctors: outcomes and standards for undergraduate medical education. General Medical Council, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.General Medical Council. Clinical placements for medical students: advice supplementary to Tomorrow's Doctors (2009). London: General Medical Council, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.General Medical Council. The state of medical education and practice in the UK report: 2014. General Medical Council; 2014. http://www.gmc-uk.org/SOMEP_2014_FINAL.pdf_58751753.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liberati A, Altman D, Tetzlaff J et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:W65–94. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monrouxe LV, Grundy L, Panagoulas E et al. How prepared are UK medical graduates for practice? 2013. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42013005305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R et al. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev 2012;1:10 10.1186/2046-4053-1-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reed DA, Beckman TJ, Wright SM et al. Predictive validity evidence for medical education research study quality instrument scores: quality of submissions to JGIM's Medical Education Special Issue. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:903–7. 10.1007/s11606-008-0664-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care: assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 2000;320:50–2. 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic reviews: CRDs guidance for undertaking reviews in healthcare. University of York, 2009. https://www.york.ac.uk/crd/SysRev/!SSL!/WebHelp/SysRev3.htm 1_3_UNDERTAKING_THE_REVIEW.htm [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carling J. Are graduate doctors adequately prepared to manage acutely unwell patients? Clin Teach 2010;7:102–5. 10.1111/j.1743-498X.2010.00341.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fox FE, Doran NJ, Rodham KJ et al. Junior doctors’ experiences of personal illness: a qualitative study. Med Educ 2011;45:1251–61. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04083.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Illing JC, Morrow GM, Rothwell nee Kergon CR et al. Perceptions of UK medical graduates’ preparedness for practice: a multi-centre qualitative study reflecting the importance of learning on the job. BMC Med Educ 2013;13:34 10.1186/1472-6920-13-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hobson J. Will our junior doctors be ready for the next major incident? A questionnaire audit on major accident awareness across three NHS Trusts in Wales. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000061. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.General Medical Council. A National training survey 2012: key findings 2012. http://www.gmc-uk.org/National_training_survey_2012_key_findings_report.pdf_49280407.pdf

- 30.General Medical Council. National training survey 2011. http://www.gmc-uk.org/NTS_trainee_survey_2011.pdf_45270429.pdf

- 31.General Medical Council. National Training Survey 2010. http://www.gmc-uk.org/static/documents/content/Training_survey-FINAL2010.pdf

- 32.General Medical Council. National Training Survey 2008–2009. GMC, 2009. http://www.gmc-uk.org/National_Training_Surveys_2008_09_20090929.pdf_30512348.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.General Medical Council. National Training Survey—Key findings 2013. http://www.gmc-uk.org/National_training_survey_2013_key_findings_report_1013.pdf_56436856.pdf

- 34.Goldacre MJ, Lambert TW, Svirko E. Foundation doctors’ views on whether their medical school prepared them well for work: UK graduates of 2008 and 2009. Postgrad Med J 2014;90:63–8. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldacre MJ, Taylor K, Lambert TW. Views of junior doctors about whether their medical school prepared them well for work: questionnaire surveys. BMC Med Educ 2010;10:78 10.1186/1472-6920-10-78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bleakley A, Brennan N. Does undergraduate curriculum design make a difference to readiness to practice as a junior doctor? Med Teach 2011;33:459–67. 10.3109/0142159X.2010.540267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watmough S, Cherry MG, O'Sullivan H. A comparison of self-perceived competencies of traditional and reformed curriculum graduates 6 years after graduation. Med Teach 2012;34:562–8. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.675457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tallentire VR, Smith SE, Wylde K et al. Are medical graduates ready to face the challenges of Foundation training? Postgrad Med J 2011;87:590–5. 10.1136/pgmj.2010.115659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morrow G, Johnson N, Burford B et al. Preparedness for practice: the perceptions of medical graduates and clinical teams. Med Teach 2012;34:123–35. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.643260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atrey A, Hunter J, Gibb PA et al. Assessing and improving the knowledge of orthopaedic foundation-year doctors. Clin Teach 2010;7:41–6. 10.1111/j.1743-498X.2009.00334.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown JM, Watmough S, Cherry MG et al. How well are graduates prepared for practice when measured against the latest GMC recommendations? Br J Hosp Med 2010;71:159–63. 10.12968/hmed.2010.71.3.46981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matheson C, Matheson D. How well prepared are medical students for their first year as doctors? The views of consultants and specialist registrars in two teaching hospitals. Postgrad Med J 2009;85:582–9. 10.1136/pgmj.2008.071639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Estcourt C, Theobald N, Evans D et al. How do UK medical graduates rate their knowledge and skills in sexual health and HIV medicine? A national survey. Int J STD AIDS 2009;20:324–9. 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brennan N, Corrigan O, Allard J et al. The transition from medical student to junior doctor: today's experiences of Tomorrow's Doctors. Med Educ 2010;44:449–58. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03604.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Franklin BD, Reynolds M, Shebl NA et al. Prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a three-centre study of their prevalence, types and causes. Postgrad Med J 2011;87:739–45. 10.1136/pgmj.2011.117879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kavanagh P, Boohan M, Savage M et al. Evaluation of a final year work-shadowing attachment. Ulster Med J 2012;81:83–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kilminster S, Zukas M, Quinton N et al. Preparedness is not enough: understanding transitions as critically intensive learning periods. Med Educ 2011;45:1006–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04048.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ross S, Ryan C, Duncan EM et al. Perceived causes of prescribing errors by junior doctors in hospital inpatients: a study from the PROTECT programme. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:97–102. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ryan C, Ross S, Davey P et al. Junior doctors’ perceptions of their self-efficacy in prescribing, their prescribing errors and the possible causes of errors. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013;76:980–7. 10.1111/bcp.12154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tallentire VR, Smith SE, Skinner J et al. The preparedness of UK graduates in acute care: a systematic literature review. Postgrad Med J 2012;88:365–71. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2011-130232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wijnen-Meijer M, Kilminster S, Van Der Schaaf M et al. The impact of various transitions in the medical education continuum on perceived readiness of trainees to be entrusted with professional tasks. Med Teach 2012;34:929–35. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.714875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ahmed M, Arora S, Carley S et al. Junior doctors’ reflections on patient safety. Postgrad Med J 2012;88:125–9. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2011-130301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seden K, Kirkham JJ, Kennedy T et al. Cross-sectional study of prescribing errors in patients admitted to nine hospitals across North West England. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002036 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davis D, MacLullich A. Understanding barriers to delirium care: a multicentre survey of knowledge and attitudes amongst UK junior doctors. Age Ageing 2009;38:559–63. 10.1093/ageing/afp099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.George JT, Warriner D, McGrane DJ et al. Lack of confidence among trainee doctors in the management of diabetes: the Trainees Own Perception of Delivery of Care (TOPDOC) Diabetes Study. QJM 2011;104:761–6. 10.1093/qjmed/hcr046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gordon JT. Emergency department junior medical staff's knowledge, skills and confidence with psychiatric patients: a survey. Psychiatrist 2012;36:186–8. 10.1192/pb.bp.111.035188 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mastoridis S, Shanmugarajah K, Kneebone R. Undergraduate education in trauma medicine: the students’ verdict on current teaching. Med Teach 2011;33:585–7. 10.3109/0142159X.2011.576716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Naghavi SHR, Sanati KA. Accidental blood and body fluid exposure among doctors. Occup Med 2009;59:101–6. 10.1093/occmed/kqn167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elsayed H, Roberts R, Emadi M et al. Chest drain insertion is not a harmless procedure—are we doing it safely? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2010;11:745–8. 10.1510/icvts.2010.243196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McGettigan P, McKendree J, Reed N et al. Identifying attributes required by Foundation Year 1 doctors in multidisciplinary teams: a tool for performance evaluation. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:225–32. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]