Abstract

Objectives

As of 1 November 2015, the Saudi Ministry of Health had reported 1273 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS); among these cases, which included 9 outbreaks at several hospitals, 717 (56%) patients recovered, 14 (1%) remain hospitalised and 543 (43%) died. This study aimed to determine the epidemiological, demographic and clinical characteristics that distinguished cases of MERS contracted during outbreaks from those contracted sporadically (ie, non-outbreak) between 2012 and 2015 in Saudi Arabia.

Design

Data from the Saudi Ministry of Health of confirmed outbreak and non-outbreak cases of MERS coronavirus (CoV) infections from September 2012 through October 2015 were abstracted and analysed. Univariate and descriptive statistical analyses were conducted, and the time between disease onset and confirmation, onset and notification and onset and death were examined.

Results

A total of 1250 patients (aged 0–109 years; mean, 50.825 years) were reported infected with MERS-CoV. Approximately two-thirds of all MERS cases were diagnosed in men for outbreak and non-outbreak cases. Healthcare workers comprised 22% of all MERS cases for outbreak and non-outbreak cases. Nosocomial infections comprised one-third of all Saudi MERS cases; however, nosocomial infections occurred more frequently in outbreak than non-outbreak cases (p<0.001). Patients contracting MERS during an outbreak were significantly more likely to die of MERS (p<0.001).

Conclusions

To date, nosocomial infections have fuelled MERS outbreaks. Given that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a worldwide religious travel destination, localised outbreaks may have massive global implications and effective outbreak preventive measures are needed.

Keywords: INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Confirmed outbreak and non-outbreak cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus infections in Saudi Arabia from September 2012 through October 2015 reported to the Saudi Ministry of Health (MOH) were abstracted and analysed.

This is the first report to retrieve the epidemiological, demographic and clinical characteristics of MERS data from this database and analyse these data using univariate and descriptive statistical analyses.

However, major leadership changes in the Saudi MOH during the study period led to alterations in the data collection forms as well as the surveillance system.

These alterations caused some inconsistencies in the data acquired from the Saudi MOH database that may limit the interpretation of the study results.

Introduction

Following the isolation of a previously unknown coronavirus (CoV) from the sputum of a man aged 60 years in 2012,1 1618 laboratory-confirmed cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) have been reported throughout 26 countries, with 579 cases resulting in death.2 The vast majority of these 26 countries reported MERS cases after experiencing an exportation event from the Arabian Peninsula.3 4 Most cases to date have occurred in Saudi Arabia, followed by South Korea, which experienced an outbreak of MERS after the return of an infected businessman who had been travelling in Middle East.5

The exact zoonotic source of MERS-CoV and its mode of transmission in humans remain unclear. Although related sequences have been detected in several bat species,6 MERS-CoV has not been isolated from bats. However, MERS-CoV has been isolated from dromedary camels. A high rate of seropositivity has been confirmed in the camels of Arabian Peninsula, with no evidence of MERS-CoV infection detected in cows, goats or sheep.7–10 One study isolated the full MERS-CoV genome sequences from a dromedary camel and from a patient who died of laboratory-confirmed MERS-CoV infection after close contact with camels; the two isolates were identical. According to serological data, MERS-CoV had been circulating in the camel—but not in the patient—before human infection occurred, suggesting that MERS-CoV had been transmitted to the patient via the infected camel.11

Whether MERS-CoV is new to camel or human populations or whether it has been present but undetected for years remains unknown. Nonetheless, MERS-CoV was initially regarded primarily as a zoonotic pathogen, with only limited documentation of person-to-person transmission. However, MERS outbreaks of varying proportions have since occurred across Saudi Arabia; additionally, apparent cases of sustained secondary transmission have occurred in family clusters12 13 and healthcare facilities.14 15

Much remains unknown about MERS, including the risk factors associated with MERS-CoV transmissions in outbreak and non-outbreak settings. Here, we aimed to increase our understanding of the spread and mode of transmission of MERS-CoV by comparing the epidemiological, demographic and clinical characteristics of outbreak and non-outbreak MERS-CoV infections from September 2012 to October 2015 as reported to the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Health (MOH).

Materials and methods

Demographic and clinical data were obtained through the use of standardised contact tracing forms populated by the public health database maintained by the MOH Command & Control Center (CCC). According to the CCC, a confirmed MERS-CoV case is defined as a suspected case with laboratory confirmation of MERS-CoV infection. A suspected case of MERS-CoV in adults (>14 years) is defined as follows: (1) acute respiratory illness with clinical or radiological evidence of pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome; (2) a hospitalised patient with healthcare-associated pneumonia based on clinical and radiological evidence; (3) upper or lower respiratory tract illness within 2 weeks of exposure to a confirmed or probable case of MERS-CoV infection; or (4) unexplained acute febrile illness (≥38°C) presenting with body aches, headache, diarrhoea or nausea/vomiting, with or without respiratory symptoms, and with leucopoenia.

Data and statistical analyses

All data collected were stored and analysed using SAS (V.9.4) software. Univariate and descriptive statistics were conducted to estimate proportions. Associations between age and two variables (gender and death) were assessed using a χ2 test. χ2 analysis using Yates' correction was performed on the data set to compare case characteristics among outbreak and non-outbreak cases. Distributions of time between onset and confirmation, onset and notification and onset and death (among patients that died) were also determined for outbreak and non-outbreak cases. All reported p values are two-tailed and were considered to be statistically significant at p<0.05.

Results

Distribution of confirmed MERS-CoV cases over time in Saudi Arabia

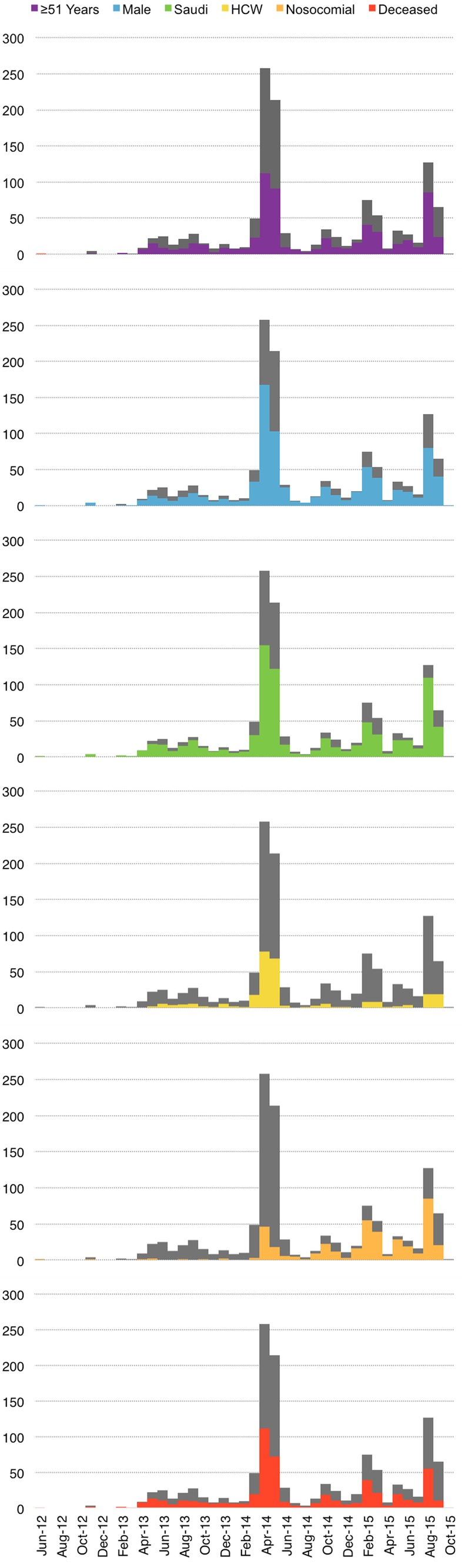

The prevalence of MERS-CoV was highest in the Riyadh region with 46.91% of the total reported cases, followed by the Jeddah (21%), AlAhsa (5.69%), AlMadinah Almonowarah (4.81%), Eastern (4.73%), AlTaif (4.33%) and Makkah (3.29%) regions. The remaining regions comprised 9.14% of the total reported cases (figure 1). More than 31% of all confirmed cases of MERS-CoV in Saudi Arabia were reported in April and May 2014. The highest number of outbreaks was reported to have occurred in April and May 2014, the second highest in September 2015 and the third highest in February and March 2015.

Figure 1.

Incidence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections (1250 confirmed cases) across the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Demographic characteristics

During the study period, a total of 1250 patients from 0 to 109 years old were reported as infected with MERS-CoV in Saudi Arabia. MERS-CoV was prevalent among individuals who were 30 years or older; in contrast, individuals who were 26 years or younger exhibited very low incidence. The distribution of age for all reported cases was almost normal, with a mean of 50.825 years and an SD of 19.494 years. MERS-CoV was more prevalent in men (64.77% of total reported cases) than in women. Women had an average age of 48 years (SD, 19 years), with a minimum of zero and maximum of 90 years. Men had an average age of 52 years (SD, 19 years), with a minimum of zero and a maximum of 109 years (table 1). We found a significant association between age and gender (χ2=15.22; p<0.01) and between gender and death for patients diagnosed with MERS-CoV (χ2=12.75; p<0.01).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics in Middle East respiratory syndrome infection cases reported in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia from 2012 to 2015

| Demographic characteristics (n) | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years (1244) | ||

| 0–10 | 41 | 3.30 |

| 11–25 | 63 | 8.36 |

| 26–39 | 292 | 31.83 |

| 40–109 | 848 | 68.17 |

| Gender (1246) | ||

| Female | 439 | 35.23 |

| Male | 807 | 64.77 |

| Occupational status (172) | ||

| Employed | 22 | 12.79 |

| Unemployed | 40 | 23.26 |

| Retired | 31 | 21.51 |

| Private | 37 | 18.02 |

| Other | 42 | 24.42 |

| Main reason for testing (1247) | ||

| Healthcare worker | 249 | 19.97 |

| Household | 138 | 11.07 |

| Suspect | 860 | 68.97 |

| Healthcare worker (1244) | ||

| Yes | 275 | 22.11 |

| No | 969 | 77.89 |

| Does the patient raise camels? (205) | ||

| Yes | 29 | 14.15 |

| No | 176 | 85.85 |

| During the 14 days before the patient became sick, did he/she travel outside or inside Saudi Arabia? (205) | ||

| Yes | 195 | 95.12 |

| No | 10 | 4.88 |

| Was the patient hospitalised when a positive result was obtained? (450) | ||

| Yes | 413 | 91.78 |

| No | 37 | 8.22 |

| Did the patient visit any healthcare facilities during the 14 days before onset of symptoms? (245) | ||

| Yes | 98 | 40 |

| No | 109 | 44.49 |

| Unknown | 38 | 15.51 |

| Does the patient smoke? (205) | ||

| Yes | 36 | 17.56 |

| No | 169 | 82.44 |

| Is the patient diabetic? (278) | ||

| Yes | 220 | 79.14 |

| No | 58 | 20.86 |

| Did the patient die before October 2015? (1250) | ||

| Yes | 535 | 42.80 |

| No | 715 | 57.20 |

Online supplementary table S1 presents the nationalities of patients diagnosed with MERS-CoV in Saudi Arabia. Most patients were Saudi (66%), followed by Filipino (10.99%), Indian (3.99%) and Yemeni (3.69%) nationalities.

bmjopen-2016-011865supp_table.pdf (175.3KB, pdf)

Univariate analysis for outbreak versus non-outbreak cases

Univariate analysis revealed that older individuals—namely, those older than the mean age of 50.825 years—represented a larger than expected proportion of outbreak than of non-outbreak cases (p<0.001; table 2). The prevalence of MERS-CoV infections among men was comparable for outbreak and non-outbreak cases (p=0.239; table 2). Similarly, approximately two-thirds of all Saudi MERS diagnoses occurred among Saudi nationals for outbreak and non-outbreak cases (p=0.558; table 2). Healthcare workers comprised 22% of all confirmed Saudi MERS cases for outbreak and non-outbreak cases (p=0.920; table 2). However, nosocomial infections, which comprised one-third of all confirmed Saudi MERS cases, occurred much more frequently among outbreak cases than among non-outbreak cases (p<0.001). Patients who became infected during outbreaks were more likely to die of MERS than those infected during non-outbreak conditions (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with confirmed Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia from 2012 to 2015 evaluated by outbreak versus non-outbreak conditions

| Outbreak cases |

Non-outbreak cases |

χ² | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=485 |

N=765 |

|||||

| n | Per cent | n | Per cent | |||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| ≥51 | 281 | 58 | 362 | 47 | 12.66 | <0.001 |

| <51 | 204 | 42 | 401 | 52 | ||

| Unknown (UNK) | 0 | 2 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 323 | 67 | 484 | 63 | 1.39 | 0.239 |

| Female | 160 | 33 | 279 | 36 | ||

| UNK | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Nationality | ||||||

| Saudi | 331 | 68 | 509 | 67 | 0.34 | 0.558 |

| Non-Saudi | 153 | 32 | 255 | 33 | ||

| UNK | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Healthcare worker (HCW) | ||||||

| Yes | 108 | 22 | 167 | 22 | 0.01 | 0.920 |

| No | 375 | 77 | 594 | 77 | ||

| UNK | 2 | 4 | ||||

| Patient hospitalised prior to onset of MERS symptoms (nosocomial infection) | ||||||

| Yes | 193 | 40 | 220 | 29 | 15.84 | <0.001 |

| No | 292 | 60 | 545 | 71 | ||

| Reason for testing (mode of transmission) | ||||||

| Suspect | 357 | 74 | 503 | 66 | 22.85 | <0.001 |

| HCW | 99 | 20 | 150 | 20 | ||

| Household | 27 | 6 | 110 | 14 | ||

| UNK | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Reason for testing (symptoms presented) | ||||||

| Group 1 | 107 | 22 | 288 | 28 | 100.84 | <0.001 |

| Group 2 | 96 | 20 | 65 | 8 | ||

| Group 3 | 11 | 2 | 35 | 5 | ||

| Group 4 | 140 | 29 | 288 | 28 | ||

| Group 5 | 128 | 26 | 85 | 11 | ||

| Group 6 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | ||

| UNK | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Outcome | ||||||

| Deceased | 245 | 51 | 290 | 38 | 18.76 | <0.001 |

| Alive | 240 | 49 | 475 | 6% | ||

Yates’ correction was used for all χ2 calculations.

Of the patients reporting data on camel exposure, 17% of the 123 non-outbreak cases and 10% of the 81 outbreak cases indicated that they owned or raised camels; this difference was not statistically significant.

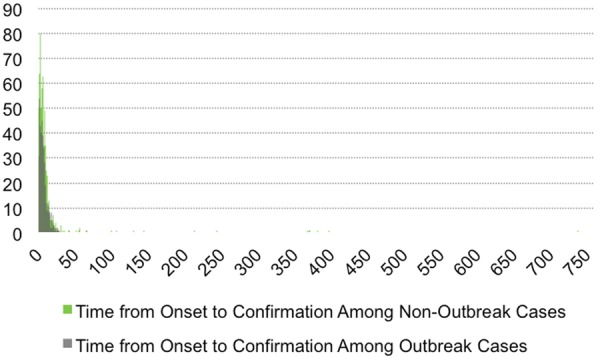

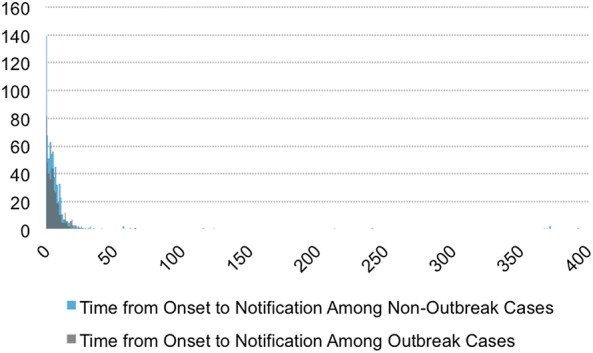

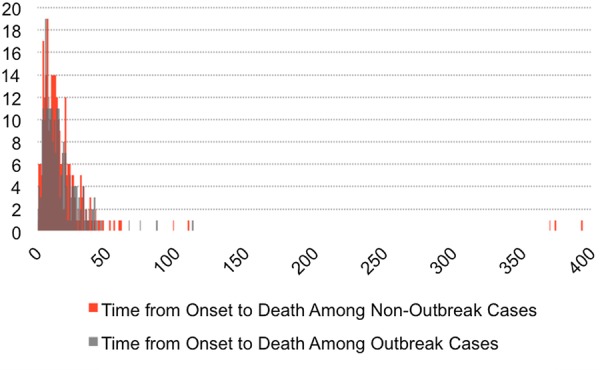

Distributions of time between onset and the confirmation, notification and death

The average time from onset to confirmation was 6.6 days for outbreak cases and 11.9 days for non-outbreak cases. For outbreak cases and non-outbreak cases, the average time from onset to notification was 5.3 and 9.2 days, respectively. Among patients who died, the average time from onset to death was 15.6 days for outbreak cases and 19.5 days for non-outbreak cases. All three distributions were long-tailed, and non-outbreak cases were skewed further right (figures 2–5).

Figure 2.

Epidemiological curve showing the number of cases of MERS-CoV infection and various patient characteristics in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia by month and year of confirmation. HCW, healthcare worker.

Figure 3.

Histogram of the time from disease onset to MERS-CoV confirmation for outbreak and non-outbreak cases. Average time from onset to confirmation was 6.6 days for outbreak cases and 11.9 days for non-outbreak cases.

Figure 4.

Histogram of time from disease onset to notification for outbreak and non-outbreak cases. Average time from onset to notification was 5.3 days for outbreak cases and 9.2 days for non-outbreak cases.

Figure 5.

Histogram of time from onset to death for outbreak and non-outbreak in those cases ending in death. Average time from onset to death among patients who died was 15.6 days for outbreak cases and 19.5 days for non-outbreak cases.

Discussion

Using the Saudi MOH CCC public health data set on MERS cases reported to have occurred from September 2012 to September 2015, we found three factors distinguishing outbreak and non-outbreak cases: (1) patients older than the mean age of 51 years represented a larger than expected fraction of outbreak than of non-outbreak cases, (2) nosocomial infections occurred much more frequently among outbreak cases than among non-outbreak cases and (3) patients infected during outbreaks were more likely to die of MERS-CoV infection than those infected during non-outbreak conditions (table 2).

Given that age was associated with death, it is worth noting that the third factor may be explained in part by the over-representation of older individuals among the outbreak cases. Although age was also associated with gender, we found that the proportion of MERS-CoV infections in men was approximately two-thirds for outbreak and non-outbreak cases (table 2). However, the general over-representation of men is consistent with many previous studies showing predominantly male patients with MERS-CoV.3 16 17

Our results also showed that healthcare workers comprised 22% of all Saudi MERS cases diagnosed up to October 2015 (table 2). This percentage is in agreement with a 2014 WHO report stating that 109 of the 402 (∼25%) reported MERS-CoV infections in the Jeddah (Saudi Arabia) 2014 outbreak occurred in healthcare workers.16 Areas neighbouring Saudi Arabia, including the city of Al-Ain in the United Arab Emirates, also reported MERS-CoV infections in 16 healthcare workers out of 23 total cases.17 Additionally, during the large South Korean outbreak in 2015, 14% of the infected cases were in healthcare workers.5

Another 2014 WHO report stated that most person-to-person MERS-CoV infections likely occurred in healthcare settings.18 We found that nosocomial transmissions comprised one-third of all Saudi MERS-CoV cases reported to date. Importantly, these nosocomial infections occurred more frequently in outbreak cases than in non-outbreak cases, suggesting that nosocomial infections fuelled outbreaks (table 2). The first outbreak in Al-Hasa, Saudi Arabia, (2013) provided valuable information about MERS-CoV transmission in a healthcare setting. The outbreak started in a haemodialysis unit of a private hospital in Al-Hasa, but subsequently spread to three other hospitals. Phylogenetic analysis of the outbreak showed that only eight of the epidemiological transmissions were related, indicating multiple zoonotic introductions of MERS-CoV.18

To date, MERS-CoV has been detected in camels from Saudi Arabia, Oman, Qatar, Jordan and Kenya,7 8 10 19 20 and it has been shown that humans can acquire MERS-CoV directly from dromedary camels.21 Since camel exposure data (ie, whether the patient owned or raised camels) were gathered for only 204 of the 1250 cases in the database used by this study, we did not include this information in table 2. Nonetheless, we found that 17% of the 123 non-outbreak cases and 10% of the 81 outbreak cases reporting data on camel exposure indicated that the patients owned or raised camels. Although this difference was not statistically significant, this result suggested that camel exposure, and thus zoonotic transmission, might be more common among sporadic, non-outbreak cases than among outbreak cases. A full analysis of this relationship will require more vigilant collection of camel exposure data.

This study was limited by the information available in the Saudi MOH CCC public health data set on MERS-CoV infections that were reported to have occurred between September 2012 and October 2015. The surveillance system and data collection forms were inconsistent over the years during which these data were acquired, likely due to major leadership changes in the MOH. The outbreak cases have thus far been confirmed faster than non-outbreak cases, indicating that improved future surveillance may allow for faster identification of sporadic cases (figure 5).

Conclusions

Although it has been 3 years since MERS-CoV was first identified in humans, cases continue to occur in household and healthcare settings, though our results indicated that most person-to-person transmissions involved healthcare-associated infections. Nosocomial outbreaks likely begin when a primary patient seeks care and then escalates due to insufficient implementation of scalable infection control measures. Our results indicate that the best way to control MERS-CoV infections may be to block its spread by practicing rigorous infection control measures in hospitals. Therefore, strengthening of infection control measures in healthcare settings will be critical to the prevention of future outbreaks.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Ministry of Health staff who helped in data collection.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Dalia Obeid @obeiddx92

Contributors: FSA is the study PI and wrote the manuscript. MSM developed the study design and conducted the analyses. JH interpreted the results. JSB reviewed the study design. DAO performed the statistical analyses. HMA-A, AA and ABS acquired patient demographic and clinical data from the Saudi Ministry of Health database. MNA-A participated in interpreting the clinical results and reviewed the manuscript. All authors participated in critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: This study was partially supported by a summer grant from King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (15/3171).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Office of Research Affairs of King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre (KFSH&RC; RAC #2130 033) and the Ministry of Health in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and included a waiver of informed consent. Informed consent was waived because this study involved a retrospective evaluation of publicly available data, the data collection was anonymous and no patient identity was revealed.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM et al. . Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1814–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) 2015. http://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/ (accessed 17 Oct 2015).

- 3.Bermingham A, Chand MA, Brown CS et al. . Severe respiratory illness caused by a novel coronavirus, in a patient transferred to the United Kingdom from the Middle East, September 2012. Euro Surveill 2012;17:20290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breban R, Riou J, Fontanet A. Interhuman transmissibility of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: estimation of pandemic risk. Lancet 2013;382:694–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61492-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majumder MS, Kluberg SA, Mekaru SR et al. . Mortality risk factors for Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak, South Korea, 2015. Emerging Infect Dis 2015;21:2088–90. 10.3201/eid2111.151231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Memish ZA, Mishra N, Olival KJ et al. . Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in bats, Saudi Arabia. Emerging Infect Dis 2013;19:1819–23. 10.3201/eid1911.131172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reusken CB, Haagmans BL, Müller MA et al. . Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus neutralising serum antibodies in dromedary camels: a comparative serological study. Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13:859–66. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70164-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reusken CB, Ababneh M, Raj VS et al. . Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) serology in major livestock species in an affected region in Jordan, June to September 2013. Euro Surveill 2013;18:20662 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2013.18.50.20662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corman VM, Jores J, Meyer B et al. . Antibodies against MERS coronavirus in dromedary camels, Kenya, 1992–2013. Emerging Infect Dis 2014;20:1319–22. 10.3201/eid2008.140596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer B, Müller MA, Corman VM et al. . Antibodies against MERS coronavirus in dromedary camels, United Arab Emirates, 2003 and 2013. Emerging Infect Dis 2014;20:552–9. 10.3201/eid2004.131746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azhar EI, El-Kafrawy SA, Farraj SA et al. . Evidence for camel-to-human transmission of MERS coronavirus. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2499–505. 10.1056/NEJMoa1401505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Memish ZA, Zumla AI, Al-Hakeem RF et al. . Family cluster of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2487–94. 10.1056/NEJMoa1303729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Omrani AS, Matin MA, Haddad Q et al. . A family cluster of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections related to a likely unrecognized asymptomatic or mild case. Int J Infect Dis 2013;17:e668–72. 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsiodras S, Baka A, Mentis A et al. . A case of imported Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection and public health response, Greece, April 2014. Euro Surveill 2014;19:20782 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.16.20782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hijawi B, Abdallat M, Sayaydeh A et al. . Novel coronavirus infections in Jordan, April 2012: epidemiological findings from a retrospective investigation. East Mediterr Health J 2013;19(Suppl 1):S12–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. WHO concludes MERS-CoV mission in Saudi Arabia. Geneva: World Health Organization; http://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/2014 (accessed 20 Oct 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Severe respiratory disease associated with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Assiri A, McGeer A, Perl TM et al. . Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med 2013;369:407–16. 10.1056/NEJMoa1306742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemida MG, Perera RA, Wang P et al. . Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus seroprevalence in domestic livestock in Saudi Arabia, 2010 to 2013. Euro Surveill 2013;18:20659 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2013.18.50.20659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raj VS, Farag EA, Reusken CB et al. . Isolation of MERS coronavirus from a dromedary camel, Qatar, 2014. Emerging Infect Dis 2014;20:1339–42. 10.3201/eid2008.140663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Memish ZA, Cotten M, Meyer B et al. . Human infection with MERS coronavirus after exposure to infected camels, Saudi Arabia, 2013. Emerging Infect Dis 2014;20:1012–15. 10.3201/eid2006.140402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011865supp_table.pdf (175.3KB, pdf)