Summary

Antioxidant properties of ethanol extract of Silybum marianum (milk thistle) seeds was investigated. We have also investigated the protein damage activated by oxidative Fenton reaction and its prevention by Silybum marianum seed extract. Antioxidant potential of Silybum marianum seed ethanol extract was measured using different in vitro methods, such as lipid peroxidation, 1,1–diphenyl–2–picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and ferric reducing power assays. The extract significantly decreased DNA damage caused by hydroxyl radicals. Protein damage induced by hydroxyl radicals was also efficiently inhibited, which was confirmed by the presence of protein damage markers, such as protein carbonyl formation and by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE). The present study shows that milk thistle seeds have good DPPH free radical scavenging activity and can prevent lipid peroxidation. Therefore, Silybum marianum can be used as potentially rich source of antioxidants and food preservatives. The results suggest that the seeds may have potential beneficial health effects providing opportunities to develop value-added products.

Key words: Silybum marianum (milk thistle) seeds, antioxidant activity, radical scavenging activity, oxidative DNA damage, protein oxidation, lipid peroxidation, carbonyl formation, SDS–PAGE

Introduction

Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. (Asteraceae), also known as milk thistle, is an important herbal medicine. It is grown primarily for the extraction of its active component (silymarin) from edible seeds, which has been used to treat liver disorders. The liver-protecting ability of silymarin is due to the antioxidant and free radical scavenging properties. Silybum marianum seeds contain more than seven flavonolignans. Many studies have reported the biological evaluation of silymarin, such as in cancer chemoprevention and hepatoprotection (1, 2). Silymarin has the ability to scavenge free radicals, it has been found to increase the production of glutathione in hepatocytes and the activity of superoxide dismutase in erythrocytes (3). In one animal study it has been shown to increase intracellular glutathione level by as much as 50% (3).

Flavonolignans showed radical scavenging properties and protective effects against the damage of lipid membranes (4) and low-density lipoproteins (5). The antioxidant effect is due to the modulation of pathways such as cell growth, apoptosis and differentiation (6).

Reactive oxygen species (superoxide radical, hydroxyl radical (˙OH) and lipid peroxide (LOO˙) radicals) may cause many diseases such as cancer and Alzheimer’s (7). They are generated in human body as a by-product of the normal biochemical reactions and increased exposure to the environmental stress (8). Oxidation of fatty acids in the cell membranes can disrupt their fluidity and permeability and damage macromolecules, such as DNA, RNA, protein and other cellular components (9). Silymarin supports the normal fluidity of cell membrane by interacting with its components (10).

Many publications show the inhibitory effects of plant extracts or their components against protein oxidation and DNA damage caused by reactive oxygen species (11–13). To our knowledge, this is the first study that has investigated the inhibition ability of DNA damage, protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation by ethanol extract of S. marianum seeds in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Seed sample

Cultivated Silybum marianum seeds were harvested in the autumn of 2012 from the field of the Department of Field Crops, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Dicle, Diyarbakır, Turkey. The extract was prepared from dried S. marianum seeds, which were ground into fine powder using blender (model 7011S; Waring, Atlanta, GA, USA).

Chemicals

The 1,1–diphenyl–2–picryl–hydrazyl (DPPH), 3–(2–pyridyl)–5,6–bis(4–phenyl–sulfonic acid)–1,2,4–triazine (Ferrozine), butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA), trichloroacetic acid (TCA), acetone, agarose, Bromophenol Blue, sodium chloride, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), glacial acetic acid, Coomassie Brillant Blue R–250 and Trizma® base were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich GmbH (Steinheim, Germany). Potassium acetate and butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Ethidium bromide was obtained from Amresco LLC (Solon, OH, USA).

Extraction procedure

Silybum marianum seeds were ground into fine powder with blender to a diameter of 0.4 mm (14). Silymarin was extracted in a two–step process in which powdered seeds were first defatted. In order to defat the seeds, about 10 g of finely powdered samples were weighed and extracted with petroleum ether (370 mL) for 4 h and then with ethanol (350 mL) for 8 h in a Soxhlet apparatus (Sigma-Aldrich). Ethanol solution was evaporated at a temperature not exceeding 40 °C and ethanol extract of seeds (1.08 g) was obtained as soft yellow powder.

Determination of total phenolic content

The phenolic content of milk thistle seed extract was measured with the Folin-Ciocalteau method (15). A mass concentration of 0.5 mg/mL of stock solution of the extract was prepared in ethanol. Then, 40 µL of the sample and the control were diluted with 1160 µL of water and 200 µL of 2 M Folin-Ciocalteu agent. The absorbance was determined at λ=765 nm. A standard gallic acid solution (50–400 µg/mL) was used to construct the calibration curve. The phenolic content was expressed in µg of gallic acid equivalents (GAE). The equation below was used to calculate the concentration of phenolic compounds:

Determination of total flavonoid content

The flavonoid content was determined by the previously described method (16). The stock solution of 0.5 mg/mL of milk thistle seeds was prepared in ethanol. In 10–mL test tube, 1 mL of extract, 0.1 mL of 10% Al(NO3)3, 0.1 mL of 1 M CH3COOK and 3.8 mL of methanol were mixed. The reaction mixture was incubated at 25 oC for 40 min. The absorbance was measured at λ=415 nm. The standard curve for total flavonoids was made using quercetin standard solution (1–25 µg/mL). The equation below was used to measure the concentration of flavonoid compounds expressed as quercetin equivalents (QE):

DPPH radical scavenging activity assay

The 1,1–diphenyl–2–picryl–hydrazil (DPPH) radical scavenging activity of S. marianum seeds was studied using previously reported procedure (17). A volume of 3 mL of S. marianum seed ethanol extract solutions of different concentrations (5, 10, 25, 50, 100 and 150 µg/mL) was mixed with 1 mL of 0.1 mM DPPH. The mixture was kept at room temperature for 30 min. Then the absorbance was measured at λ=517 nm with a Cary 100 Bio UV/Vis spectrophotometer (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). The following equation was used to measure the radical scavenging activity:

Scavenging effect=

Reducing power assay

The reducing power of the S. marianum seeds was evaluated using the procedure described previously (18), with some modifications. Butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) and butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) were used as positive controls. In a test tube, 1 mL of sample (5–150 µg/mL), 2.5 mL of 0.2 M phosphate buffer (PBS; pH=6.6) and 2.5 mL of 1% K3Fe(CN)6 solution were mixed.

After 20 min of incubation at 50 oC, 2.5 mL of 10% trichloroacetic acid were added to each mixture, and then centrifuged at 1500×g for 10 min. A supernatant volume of 2.5 mL was taken and mixed with 2.5 mL of deionized water containing 0.5 mL of 0.1% iron(III) chloride. After 10 min of incubation at room temperature the absorbance A was measured at λ=700 nm.

Lipid peroxidation assay

Rat liver homogenate preparation

The rat liver homogenate (10% by mass per volume) was prepared according to a previously reported method (19). For this study, albino Wistar rats (mass of (150±25) g) were used. Permission was obtained from Dicle University Ethical Committee (IAEC; Diyarbakır, Turkey). The animals were housed in polypropylene cages at controlled temperature ((22±3) oC). Standard formula and water were given to the animals ad libitum. The liver was removed and perfused with 120 mM potassium chloride and 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH=7.4. The ratio of liver mass per volume of solution was 1:10. In order to obtain the pellet, the samples were centrifugated at 700×g at 4 °C.

Thiobarbituric acid assay

The previously described thiobarbituric acid (TBA) assay was used to measure lipid peroxidation (20). Supernatant (100 µL) was mixed with ethanol extract (200 µL) of S. marianum seeds (5–250 µg/mL). To the reaction mixture, 100 µL of 10 mM iron(III) chloride and 100 µL of 0.1 mM ascorbic acid were added and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Supernatant absorbance was measured at λ=532 nm. The following equation was used to calculate the percentage of lipid peroxidation inhibition:

DNA damage protection capacity

DNA protection capacity of milk thistle seed extract against oxidation was determined according to Kızıl (21) using plasmid DNA. The band intensity for the forms I and II of plasmid DNA was quantified using Quantity One v. 4.5.2 software (Bio–Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Genejet miniprep kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc, Waltham, MA, USA) was employed for the isolation of plasmid DNA. The following equation was used to calculate the inhibition of the DNA cleavage:

where Sm+a is the percentage of the remaining supercoiled DNA after treatment with a mix consisting of buffer, DNA, H2O2 and UV, and the agent (Silybum marianum extract), Sc is the percentage of the remaining supercoiled DNA in the control (untreated plasmid), and Sm is the percentage of the remaining supercoiled DNA with the mix, but without the agent.

Protein damage protection

Inhibition of protein carbonyl formation

The effect of milk thistle seed extract on protein oxidation was determined using a modified method of Wang et al. (22). Bovine serum albumin (BSA; 4 mg/mL) was treated with iron(III) chloride (50 µM), hydrogen peroxide (1 mM) and ascorbic acid (100 µM) in potassium phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH=7.4) in the presence of seed extract (10–1000 µg/mL) at 37 °C for 30 min and then the absorbance was measured at λ=370 nm. The inhibition of protein carbonyl formation was calculated as follows (21):

SDS–PAGE analysis

The inhibitory effect of the ethanol extract of S. marianum seeds on protein damage was also determined by SDS–PAGE (12). The gel was run at a maximum voltage in running buffer containing 25 mM Tris, pH=8.3, 190 mM glycine and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS). The current of 25 mA was used per gel. Coomassie Brillant Blue R–250 (0.15%) was used for staining of the gel, which was scanned with Gel Doc XR System (Bio–Rad).

Statistical analysis

In order to determine the differences between the groups, one–way ANOVA was used. Results are presented as the mean value±standard deviation of three replicates.

Results and Discussion

Phenolic and flavonoid content of S. marianum seed extract

Total phenolic content (expressed as GAE) of ethanol extract of milk thistle seeds was determined to be (620.0±4.93) µg/g. In addition to this, the flavonoid content (expressed as QE) was found to be (39.32±0.11) µg/g. These values show that the ethanol extract of milk thistle seed has good antioxidant activity. Besides that, hydroxyl groups present in the compounds isolated from the milk thistle extract have good radical scavenging activity. Pereira et al. (23) described the content of phenolics and flavonoids in milk thistle. In their study, milk thistle plant was used as dry material for infusion and pill preparation. The phenolic and flavonoid contents (expressed as GAE and catechin equivalent, respectively) were found to be (23.26±0.22) mg/g and (6.95±0.23) mg/g in infusions, and (20.92±0.45) and (3.88±0.13) mg/g in dietary supplements, respectively (23). On the other hand, Tupe et al. (24) reported phenolic content (as GAE) of methanolic plant extract of milk thistle of (18.33±0.16) mg/g. The high contents of phenolics and flavonoids obtained in infusions, dietary supplements and methanolic milk thistle plant extract may depend on the part of the plant used. Phenolics and flavonoids are very important plant components due to their radical scavenging properties (25, 26). It is well known that flavonoids have anticarcinogenic activity, antiallergenic, antiviral, antiageing and anti-inflammatory properties.

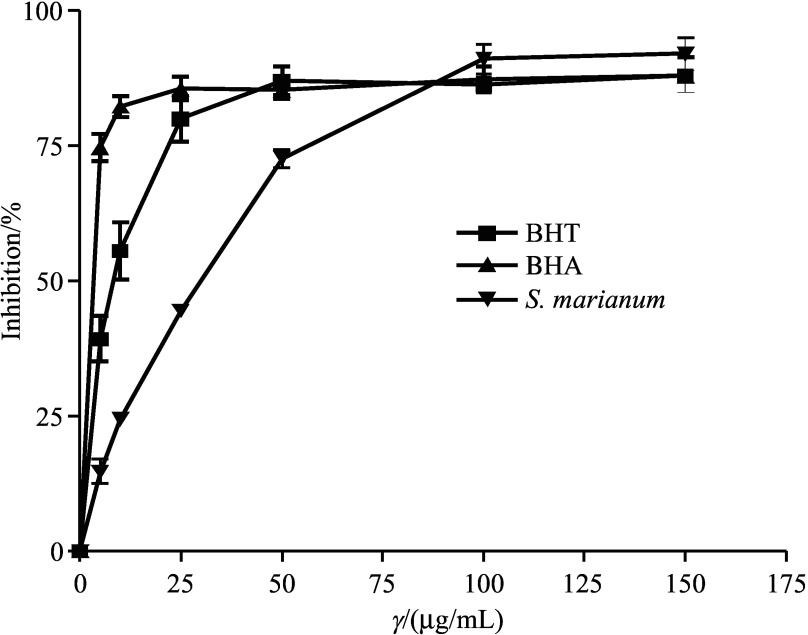

DPPH radical scavenging activity

The S. marianum extract showed a strong DPPH radical scavenging ability in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1). The order of radical scavenging activities was found to be as follows: S. marianum>BHT>BHA and was 92.0±5.2, 88.0±5.7 and 87.8±2.1 at 150 µg/mL. The antioxidant (DPPH scavenging) activity of S. marianum essential components and different tissues was also reported by Hadaruga and Hadaruga (27). There was no significant difference between the DPPH radical scavenging activity of S. marianum seed extract and both standards.

Fig. 1.

Scavenging effect of ethanol extract of Silybum marianum seeds on 1,1–diphenyl–2–picrylhydrazyl radicals. Each value is expressed as mean value±standard deviation (S.D.) (N=3). BHT= butylated hydroxytoluene, BHA=butylated hydroxyanisole

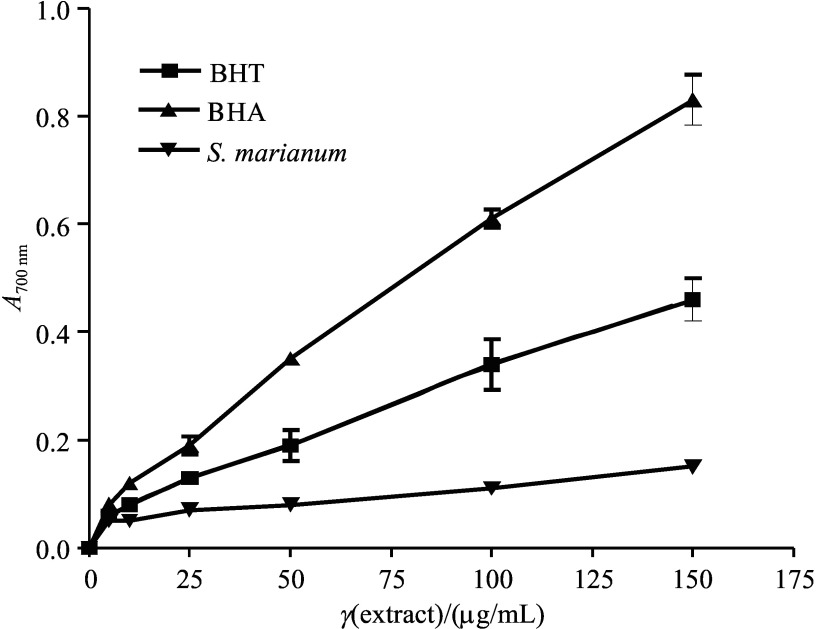

Reducing power assay

It was found that S. marianum has a benefical effect against acute and chronic liver failure. Silibinin, a major active constituent of silymarin, was found to have antitumour properties in hepatocarcinoma cell and animal models (28). The tested samples at the concentrations of 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, and 150 µg/mL exhibited a dose-dependent reducing power activity. Reducing power of 100 µg/mL of milk thistle seed extract measured as A700 nm was determined to be 0.11±0.00. On the other hand, reducing powers of BHA and BHT at 100 µg/mL measured as A700 nm were determined to be 0.61±0.03 and 0.34±0.08, respectively. The reducing power of S. marianum seed ethanol extract is shown in Fig. 2 with BHT and BHA as positive controls.

Fig. 2.

Reducing power of ethanol extract of Silybum marianum seeds, BHT and BHA measured by spectrophotometric detection at 700 nm of Fe3+–Fe2+ transformation. Each value is expressed as mean value±S.D. (N=3). Higher absorbance at 700 nm indicated greater reducing power. BHT=butylated hydroxytoluene, BHA=butylated hydroxyanisole

There are reports on antioxidant activity and reducing power of milk thistle infusions, dietary supplements and syrups (23, 28). Reducing power of infusions, dietary suplements and syrups (measured as A700 nm) was found to be 1.73±0.03, 1.10±0.02, and 0.05±0.0, respectively (23, 28). Tupe et al. (24) have investigated 19 frequently used medicinal plants and concluded that the strongest antioxidant activity was observed in Terminalia chebula since it had high phenolic content, outstanding reducing power and highest radical scavenging activity.

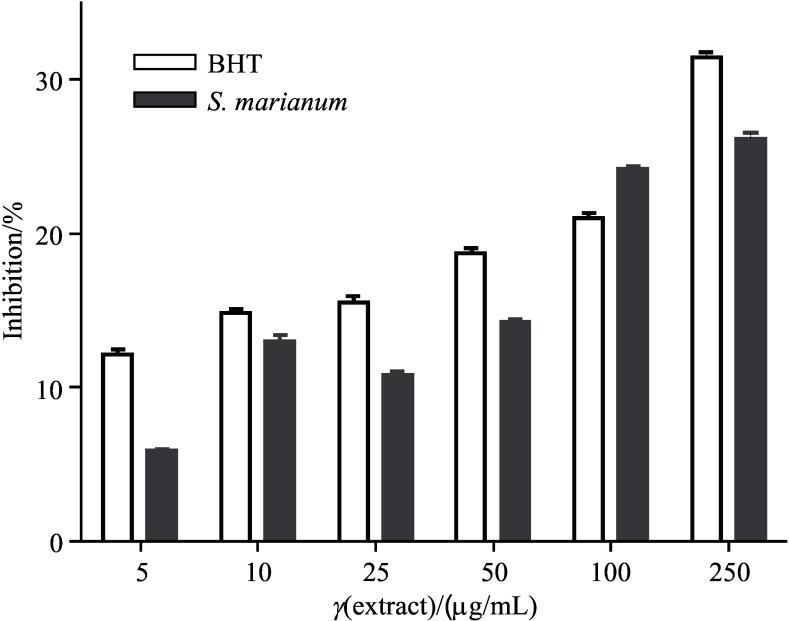

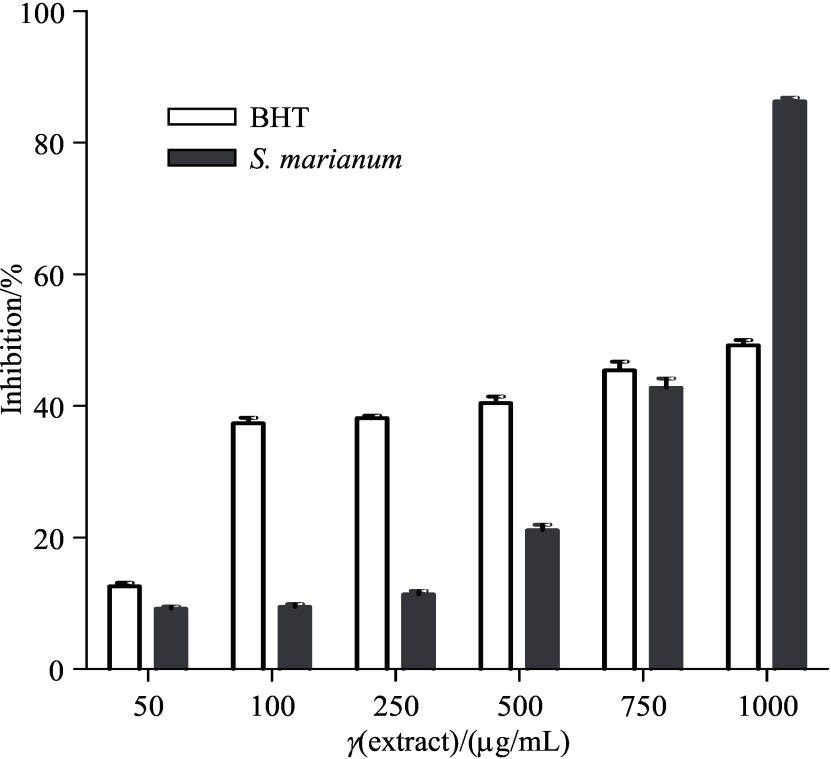

Lipid peroxidation

The compound antioxidant activity depends on their capacity to delay the oxidation by inhibiting reactive oxygen species (29). As shown in Fig. 3, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), which are formed during lipid oxidation, were measured in rat liver homogenate and it was found that the S. marianum extract moderately repressed TBARS formation. At the concentration of 250 µg/mL of S. marianum seed extract, 26.14% of TBARS formation was inhibited. BHT inhibited 31.40% at the same concentration. There were no significant differences between the activity of S. marianum seed extract and BHT. The inhibitory activity of Mangifera indica fractions against lipid peroxidation was studied by Badmus et al. (30), who found that the ethyl acetate fraction had the highest inhibitory activity against lipid peroxidation in brain homogenate (66.3%), followed by methanol (61.6%), chloroform (46.5%) and aqueous (39.5%) fractions. High percentage of lipid peroxidation inhibition of 89.1% was observed in aqueous fraction of liver homogenate, followed by ethyl acetate (71.6%), methanol (59.0%) and chloroform (48.5%) fractions.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of Fe2+-induced lipid peroxidation in rat liver homogenate by ethanol extract of Silybum marianum seeds. Each value is expressed as mean value±S.D. (N=3). BHT=butylated hydroxytoluene

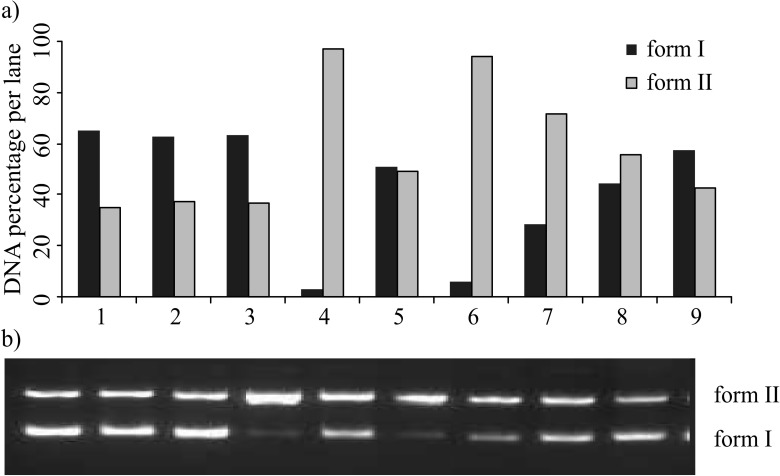

DNA damage protection

The band intensity for the forms I and II of plasmid DNA was quantified (Fig. 4a). Fig. 4b shows plasmid DNA after UV-induced photolysis of H2O2 (2.5 mM) in the presence or absence of the S. marianum etanol extract (in the concentration of 100, 500, 750 or 1000 µg/mL). The supercoiled DNA was converted to form I DNA by UV light (Fig. 4b, lane 4). Formation of form I DNA was suppresed in the presence of the extract (Fig. 4b, lanes 6–9) and the amount of form II of DNA was increased. The inhibitory activity of the ethanol extract of cultivated milk thistle seed against oxidative DNA damage was found to be 4.72, 41.08, 66.95 and 87.80% at 100, 500, 750 and 1000 µg/mL, respectively. DNA damage was suppressed with the increased concentration of the extract. The ethanol extract of milk thistle seeds showed a concentration–dependent free radical scavenging activity (Fig. 4a). The protective effect of the extract against DNA damage may be attributed to the presence of flavonoid and phenolic compounds, such as silymarin and silibinin, which can prevent the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by making complexes with cations such as copper and iron that participate in hydroxyl radical formation (5).

Fig. 4.

The quantified band intensity of the scDNA (form I) and ocDNA (form II) (a), and (b) electrophoretic pattern of pBluescript M13+DNA after UV photolysis of H2O2 in the presence or absence of ethanol extract of Silybum marianum seeds. Reaction vials contained 200 ng of supercoiled DNA (31.53 nM) in distilled water, pH=7

Inhibition of protein carbonyl formation by S. marianum seed extract

The effect of milk thistle seed extract on BSA hydroxyl radical-mediated oxidation is shown in Fig. 5. BHT and S. marianum seed extract at 50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 µg/mL decreased the free radical-induced protein damage caused by protein carbonyl group formation, induced by Fenton reaction system. The inhibitory effect of BHT at 50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 µg/mL was found to be 12.56, 37.33, 38.16, 40.43 and 45.40%, respectively, and of S. marianum seed extract at 50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 µg/mL was found to be 9.16, 9.46, 11.36, 21.10, 42.75 and 86.27%, respectively. The inhibition of protein oxidation by S. marianum seed extract may be due to its high radical scavenging activity. Inhibitory effects of methanolic extract of Feronia limonia pericarp on in vitro protein glycoxidation was studied by Kilari et al. (31). The study demonstrated that F. limonia extract was efficient in preventing oxidative protein damage, including protein carbonyl formation during glycoxidation. They proposed that the antioxidant effect of F. limonia might be due to the presence of volatile flavours and free fatty acids in the pericarp, which are involved in the inhibitory mechanisms of protein carbonyl formation.

Fig. 5.

Inhibitory effect of butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and ethanol extract of Silybum marianum seeds on protein (bovine serum albumin, BSA) oxidation, expressed as protein carbonyl inhibition induced by Fenton reaction system (Fe3+/H2O2/ascorbic acid). Each value is expressed as mean value±S.D. (N=3). All the values were statistically significantly different from the control (p<0.05)

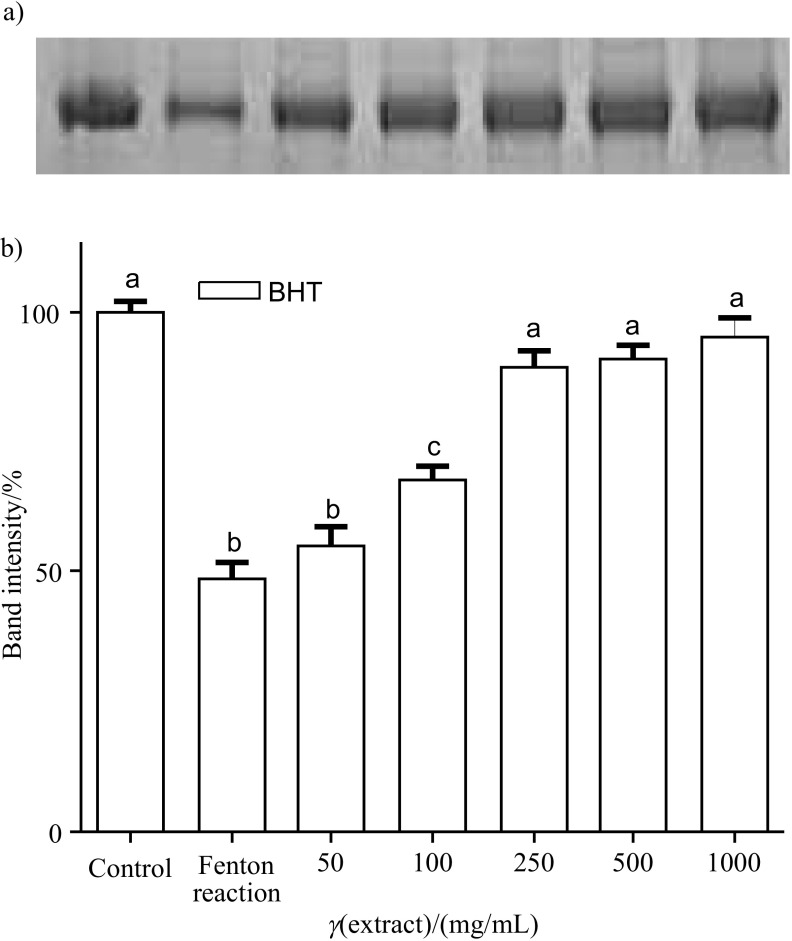

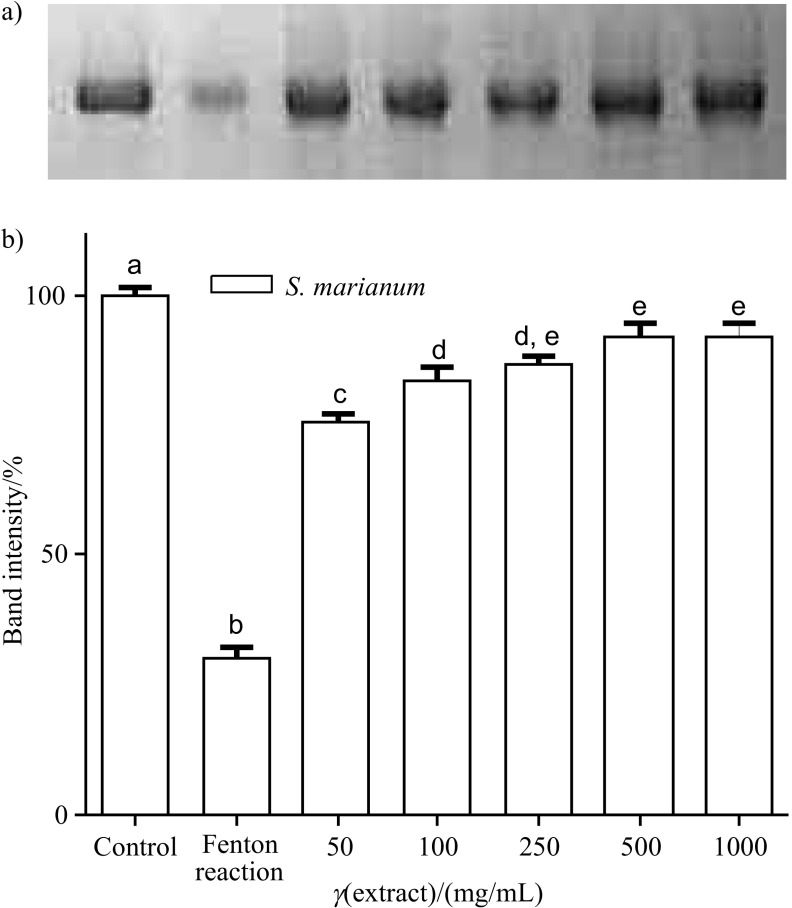

SDS–PAGE

The different concentrations of BHT and S. marianum seed extract showed inhibitory activity on BSA oxidation induced by Fenton reaction system as measured with SDS–PAGE. Figs. 6a and b and Figs. 7a and b show the band pattern of bovine serum albumin and densitometry data of the corresponding bands. Protein damage induced by Fenton reaction system was inhibited with butylated hydroxytoluene (Figs. 6a and b) and milk thistle ethanol extract (Figs. 7a and b) in a concentration between 50 and 1000 µg/mL. The inhibitory activity of BHT on BSA was found to be 24.23, 37.54, 61.45, 68.62 and 74.49%, and of S. marianum seed extract on BSA was found to be 65.70, 77.27, 81.96, 89.29 and 89.99% at the concentrations of 50–1000 µg/mL, respectively.

Fig. 6.

Protection against bovine serum albumin (BSA) oxidative damage by butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT): a) the electrophoretic pattern of BSA, and b) densitometric analysis of the corresponding band intensity. Each bar represents the mean value±S.D. (N=3). Mean values with different letters differ significantly (p<0.05), while those with the same letter are not significantly different (p>0.05)

Fig. 7.

Protection against bovine serum albumin (BSA) oxidative damage by ethanol extract of Silybum marianum seeds: a) the electrophoretic pattern of BSA, and b) densitometric analysis of the corresponding band intensity. BSA was oxidised by Fenton reaction system (Fe3+/H2O2/ascorbic acid). Each bar represents the mean value±S.D. (N=3). Mean values with different letters differ significantly (p<0.05), while those with the same letters are not significantly different at p>0.05 compared with Fenton reaction system

Conclusions

The present work investigated the in vitro antioxidative and oxidative DNA, protein and lipid damage protective effects of milk thistle (Silybum marianum) seed ethanol extract. The extract was found to have protective effect against DNA, protein and lipid oxidation induced by hydroxyl radical. The results obtained in this study show that ethanol extract of seeds can be used as a dietary supplement and it can protect DNA from damage. The inhibitory activity of seed extract against hydroxyl radical-induced DNA, protein and lipid damage may be mainly responsible for the cancer chemoprevention and hepatoprotection effects. The presence of silymarin could account for the increased antioxidant activity and enhanced DNA, protein and lipid damage protection capacity of the extract. Protection against the DNA, protein and lipid oxidation is due to phenolic and flavonoid compounds that scavenge the free radicals. These findings also imply that the presence of antioxidants can decrease the occurrence of degenerative disorders in which free-radical damage may be involed.

Acknowledgements

This research (Project no. 12–FF–20) received financial support from the Dicle University Coordination Committee of Scientific Research Projects (DUBAP), Diyarbakır, Turkey. The authors thank DUBAP for financial support.

Footnotes

Authors state that they have no conflict of interest regarding this submission.

References

- 1.Al–Anati L, Essid E, Reinehr R, Petzinger E. Silibinin protects OTA–mediated TNF–α release from perfused rat livers and isolated rat Kupffer cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2009;53:460–6. 10.1002/mnfr.200800110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jayaraj R, Deb U, Bhaskar ASB, Prasad GBKS, Lakishmana Rao PV. Hepatoprotective efficacy of certain flavonoids against microcystin induced toxicity in mice. Environ Toxicol. 2007;22:472–9. 10.1002/tox.20283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fehér J, Láng I, Deák G, Cornides A, Nékám K, Gergely P. Free radicals in tissue damage in liver diseases and therapeutic approach. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 1986;11:121–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Křen V, Kubisch J, Sedmera P, Halada P, Prikřylova V, Jegorov A, et al. Glycosylation of silybin. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1997;17:2467–74. 10.1039/a703283h [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mira L, Silva M, Manso CF. Scavenging of reactive oxygen species by silibinin dihemisuccinate. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;48:753–9. 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90053-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skottová N, Krečman V, Simánek V. Activities of silymarin and its flavonolignans upon low density lipoprotein oxidability in vitro. Phytother Res. 1999;13:535–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miguez MP, Anundi I, Sainz–Pardo LA, Lindros KO. Hepatoprotective mechanism of silymarin: no evidence for involvement of cytochrome P450 2E1. Chem Biol Interact. 1994;91:51–63. 10.1016/0009-2797(94)90006-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller AL. Antioxidant flavonoids: structure, function and clinical usage. Altern Med Rev. 1996;1:103–11. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiseman H. Dietary influences on membrane function: importance in protection against oxidative damage and disease. J Nutr Biochem. 1996;7:2–15. 10.1016/0955-2863(95)00152-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muriel P, Mourelle M. Prevention by silymarin of membrane alterations in acute CCl4 liver damage. J Appl Toxicol. 1990;10:275–9. 10.1002/jat.2550100408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emen Tanrıkut S, Çeken B, Altaş S, Pirinççioğlu M, Kızıl G, Kızıl M. DNA cleavage protecting activity and in vitro antioxidant potential of aqueous extract from fresh stems of Rheum ribes. Acta Aliment. 2013;42:461–72. 10.1556/AAlim.42.2013.4.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kızıl G, Kızıl M, Çeken B, Yavuz M, Demir H. Protective ability of ethanol extracts of Hypericum scabrum L. and Hypericum retusum Aucher against the protein oxidation and DNA damage. Int J Food Prop. 2011;14:926–40. 10.1080/10942910903491181 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kızıl M, Kızıl G, Yavuz M, Çeken B. Protective activity of ethanol extract of three Achillea species against lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation and DNA damage in vitro. Acta Aliment. 2010;39:450–63. 10.1556/AAlim.39.2010.4.7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace SN, Carrier DJ, Clausen EC. Extraction of nutraceuticals from milk thistle: part II. extraction with organic solvents. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2003;105:891–903. 10.1385/ABAB:108:1-3:891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slinkard K, Singleton VL. Total phenol analysis: automation and comparison with manual methods. Am J Enol Vitic. 1977;28:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhishen J, Mengcheng T, Jianming W. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 1999;64:555–9. 10.1016/S0308-8146(98)00102-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimada K, Fujikava K, Yahara K, Nakamura T. Antioxidative properties of xanthane on the autoxidation of soybean oil in cyclodextrin emulsion. J Agric Food Chem. 1992;40:945–8. 10.1021/jf00018a005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oyaizu M. Studies on products of browning reaction: antioxidative activity of products of browning reaction prepared from glucosamine. Jpn J Nutr. 1986;44:307–15. 10.5264/eiyogakuzashi.44.307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song JH, Simons C, Cao L, Shin SH, Hong M, Chung MI. Rapid uptake of oxidized ascorbate induces loss of cellular glutathione and oxidative stress in liver slices. Exp Mol Med. 2003;35:67–75. 10.1038/emm.2003.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lo KM, Cheung PCK. Antioxidant activity of extracts from the fruiting bodies of Agrocybe aegerita var. alba. Food Chem. 2005;89:533–9. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.03.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kızıl G, Kızıl M, Çeken B. The protective ability of ethanol extracts of Hypericum scabroides Robson & Poulter and Hypericum triquetrifolium Turra against protein oxidation and DNA damage. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2009;18:130–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang BS, Lin SS, Hsiao WC, Fan JJ, Fuh LF, Duh PD. Protective effects of an aqueous extract of Welsh onion green leaves on oxidative damage of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Food Chem. 2006;98:149–57. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.05.057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pereira C, Calhelha RC, Barros L, Queiroz MJRP, Ferreira ICFR. Synergism in antioxidant and anti–hepatocellular carcinoma activities of artichoke, milk thistle and borututu syrups. Ind Crops Prod. 2014;52:709–13. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2013.11.050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tupe RS, Kemse NG, Khaire AA. Evaluation of antioxidant potentials and total phenolic contents of selected Indian herbs powder extracts. Int Food Res J. 2013;20:1053–63. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altaş S, Kızıl G, Kızıl M, Ketani A, Haris PH. Protective effect of Diyarbakır watermelon juice on carbon tetrachloride–induced toxicity in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:2433–8. 10.1016/j.fct.2011.06.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Havsteen B. Flavonoids, a class of natural products of high pharmacological potency. Biochem Pharmacol. 1983;32:1141–8. 10.1016/0006-2952(83)90262-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hadaruga DI, Hadaruga NG. Antioxidant activity of hepatoprotective silymarin and Silybum marianum L. extract. Chem Bull ‘Politehnica’. Univ Timisoara. 2009;54:104–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pereira C, Calhelha RC, Barros L, Ferreira ICFR. Antioxidant properties, anti–hepatocellular carcinoma activity and hepatotoxicity of artichoke, milk thistle and borututu. Ind Crops Prod. 2013;49:61–5. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2013.04.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar A, Chattopadhyay S. DNA damage protecting activity and antioxidant potential of pudina extract. Food Chem. 2007;100:1377–84. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.12.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Badmus JA, Adedosu TO, Fatoki JO, Adegbite VA, Adaramoye OA, Odunola OA. Lipid peroxidation inhibition and antiradical activities of some leaf fractions of Mangifera indica. Acta Pol Pharm. 2011;68:23–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kilari EK, Putta S, Koratana R, Nagireddy NR, Qureshi AA. Inhibitory effects of methanolic pericarp extract of Feronia limonia on in vitro protein glycoxidation. Int J Pharm. 2015;11:35–42. 10.3923/ijp.2015.35.42 [DOI] [Google Scholar]