Abstract

A clinical strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae carried the blaSHV-49 gene, encoding a novel inhibitor-resistant β-lactamase of pI 7.6, derived from SHV-1 by the single substitution M69I. It also harbored a gene differing from blaSHV-11 by four silent mutations and coding for a penicillinase. Both genes were chromosome located and might represent either a species-specific gene or an acquired resistance gene.

Klebsiella pneumoniae is an opportunistic pathogen responsible for a wide range of community- and hospital-acquired infections (21). This species exhibits low-level resistance to amino and carboxy penicillins due to the production of a chromosomally encoded SHV-1-type penicillinase that is inhibited by clavulanic acid. Some isolates have high-level resistance to penicillins and reduced susceptibility to narrow-spectrum cephalosporins caused by plasmid-acquired β-lactamases, generally of the TEM-1, TEM-2, or SHV-1 type (14). Penicillinase overproduction simultaneously increases amoxicillin-clavulanate and cephalothin resistance (19). Since 1982, strains producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases derived from TEM and SHV enzymes have evolved and presented resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins (21). Since 1995, amoxicillin-clavulanate-resistant and cephalothin-susceptible clinical strains of K. pneumoniae expressing inhibitor-resistant TEM (IRT) β-lactamase (TEM-30 or TEM-31) have been reported (3, 11, 16). At present, a single inhibitor-resistant SHV-type β-lactamase, SHV-10, has been described for Escherichia coli (24). We report here SHV-49, the second enzyme of this kind, in a clinical strain of K. pneumoniae.

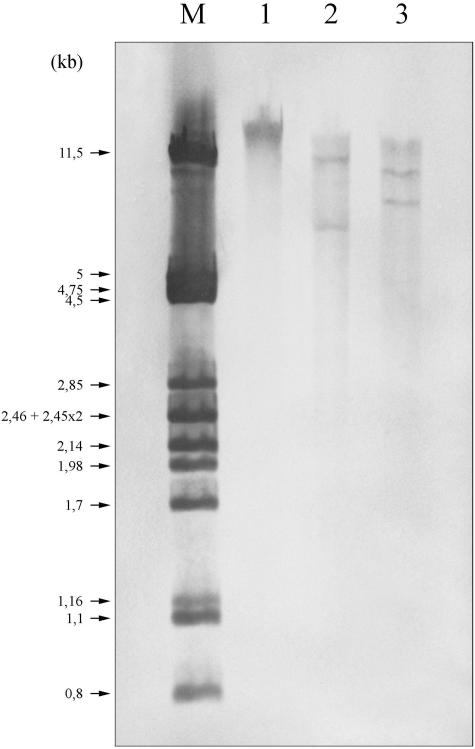

K. pneumoniae Kp238 was isolated from the wound sample of a gastrostomy catheter of a 68-year-old man hospitalized in 1997 in an intensive care unit at the Pellegrin hospital in Bordeaux (France). Two months previously he had received, for a febrile episode of unknown origin, amoxicillin-clavulanate at 6 g/day intravenously for 10 days, then orally at 3 g/day for 1 month, and finally orally at 1.5 g/day for 10 extra days. By the disk diffusion method, Kp238 presented an IRT phenotype and was also resistant to tetracycline, sulfonamides, and chloramphenicol. MICs determined by an agar dilution method in Mueller-Hinton (MH) medium (http://www.sfm.asso.fr) confirmed that it was highly resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin, ticarcillin, and piperacillin (MICs from 512 to >4,096 μg/ml) and was susceptible to cephalothin (MIC of 8 μg/ml); MICs of penicillins were only slightly reduced after addition of β-lactamase inhibitors, even with the piperacillin-tazobactam combination (Table 1). Isoelectric focusing analysis of a crude β-lactamase extract from Kp238, performed as described previously (17) on a pH 3.5 to 10 ampholin polyacrylamide gel and revealed by the iodine procedure in gel by using benzylpenicillin (75 μg/ml) as substrate, showed a single band cofocusing with an SHV-1 β-lactamase of pI 7.6. PCR amplification under standard conditions (26), using total DNA of Kp238 extracted as previously reported (9) and primers specific for bla genes that are potentially resistant to inhibitors (blaTEM, blaOXA-1, blaOXA-2, blaOXA-10, blaOXA-18, and blaPSE-1), gave negative results. Transfer by conjugation of β-lactam or other resistance markers to a nalidixic acid-resistant E. coli K-12 strain by using a filter mating technique failed to yield transconjugants. Plasmid DNA analysis of K. pneumoniae Kp238 by the alkaline-lysis method (4) did not evidence any plasmid, and transformation by electroporation of putative plasmid DNA extract into E. coli TOP10 or DH5α remained unsuccessful. Whole-cell DNA of Kp238 was then restricted by either EcoRI or HindIII and was ligated into the EcoRI or HindIII site of the pBK-CMV cloning vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). The E. coli TOP10(pE1) strain, selected on MH agar plates containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and kanamycin (50 μg/ml), was obtained with the EcoRI-digested DNA and carried the recombinant plasmid pE1. The E. coli TOP10(pH2) strain, selected on the same MH agar plates supplemented additionally with clavulanic acid (4 μg/ml), was obtained with HindIII-digested DNA and harbored the recombinant plasmid pH2. Recombinant plasmids pE1 and pH2 contained inserts of ca. 7.1 and 10.5 kb, respectively. E. coli TOP10(pE1) exhibited a penicillinase phenotype (amino and carboxy penicillin resistance partially or totally restored by the addition of β-lactamase inhibitors), whereas E. coli TOP10(pH2) displayed the same IRT phenotype as Kp238 (Table 1). Both clones elaborated a β-lactamase of pI 7.6 and gave PCR products by using blaSHV-specific primers (9). Southern blot followed by DNA-DNA hybridization using Kp238 DNA, a blaSHV-specific probe, and the digoxigenin DNA labeling and detection kit (Roche Applied Science, Meylan, France) indicated the presence of only two blaSHV genes (digested DNA) (Fig. 1, lanes 2 and 3) and argued for their chromosomal location (unrestricted DNA) (Fig. 1, lane 1). The blaSHV genes were sequenced on both strands by using laboratory-designed primers, the DYEnamic ET dye terminator kit (Amersham), and automatic sequencer ABI 310 (PE Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France).

TABLE 1.

MICs of β-lactams for the clinical isolate Kp238 and E. coli TOP10 with and without pE1 and pH2 recombinant plasmids

| Strain (recombinant plasmid) | β-Lactamase | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP | SAM | AMX | AMC | TIC | TIM | PIP | TZP | IMP | CEF | CTX | FEP | ||

| K. pneumoniae Kp238 | SHV-11 + SHV-49 | 4,096 | 4,096 | >4,096 | 4,096 | 2,048 | 512 | 512 | 512 | ≤0.1 | 8 | ≤0.1 | ≤0.1 |

| E. coli TOP10(pE1) | SHV-11 | 2,048 | 256 | 4,096 | 8 | 1,024 | 16 | 128 | 8 | ≤0.1 | 8 | ≤0.1 | ≤0.1 |

| E. coli TOP10(pH2) | SHV-49 | >4,096 | >4,096 | >4,096 | >4,096 | >2,048 | 1,024 | 2,048 | 1,024 | ≤0.1 | 8 | ≤0.1 | ≤0.1 |

| E. coli TOP10 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | ≤0.1 | 8 | ≤0.1 | ≤0.1 | |

AMP, ampicillin; SAM; ampicillin plus sulbactam (8 μg/ml); AMX, amoxicillin; AMC, amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid (2 μg/ml); TIC, ticarcillin; TIM, ticarcillin plus clavulanic acid (2 μg/ml); PIP, piperacillin; TZP, piperacillin plus tazobactam (4 μg/ml); IPM, imipenem; CEF, cephalothin; CTX, cefotaxime; FEP, cefepime.

FIG. 1.

Southern blot and hybridization with a blaSHV specific probe. Lane M, size marker consisting of the λ phage DNA restricted by PstI; lane 1, unrestricted DNA of Kp238; lane 2, Kp238 DNA digested by EcoRI; lane 3, Kp238 DNA digested by HindIII.

The nucleotide sequence of the IRT β-lactamase-encoding gene identified the novel β-lactamase SHV-49. The blaSHV-49 gene differed from blaSHV-1 (7) by the mutation G→A at position 195, leading to the amino acid substitution Met69→Ile (Table 2). Similar changes in TEM variants (TEM-32, TEM-37, TEM-40, and TEM-83) have been shown to confer an IRT phenotype (5, 13, 15, 27). Site-directed mutagenesis experiments have demonstrated that this change in the SHV-1 sequence or in the homologous OHIO enzyme conveys an inhibitor resistance due to a greatly increased hydrophobicity, altering the oxyanion hole and affecting catalysis (6, 12). The first inhibitor-resistant SHV enzyme, SHV-10, derived from the extended-spectrum β-lactamase SHV-5 by a mutation in another critical site, Ser130→Gly (24). The catalytic properties of SHV-49 were investigated after β-lactamase extraction and purification onto two successive Q-Sepharose columns with 20 mM diethanolamine (pH 9.2) and 20 mM Bis-Tris (pH 7) buffers, respectively (23). SHV-49 showed a reduced affinity for amoxicillin and ticarcillin, whereas no hydrolysis was detected against extended-spectrum cephalosporins (Table 3). The 50% inhibitory concentrations of clavulanic acid, tazobactam, and sulbactam, determined by the rate of benzylpenicillin (100 μM) hydrolysis after 3 min of preincubation, were considerably higher for SHV-49 (1.5, 2.5, and 15 μM, respectively) than those for SHV-1 (163 nM, 150 nM, and 5 μM, respectively) (23).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of nucleotide sequences of several SHV genes

| SHV variant | Promoter, −10 region | nucleotidea (amino acidb) at position

|

Reference or source | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 92 (35) | 195 (69) | 324 (112) | 402 (138) | 516 (176) | 705 (240) | 786 (268) | |||

| SHV-1 | NDd | T (Leu) | G (Met) | C (His) | A (Leu) | C (Asp) | G (Glu) | C (Thr) | 7 |

| SHV-11 | ND | A (Glnc) | T | G | G | 18 | |||

| SHV-11 | ACAAAT | A (Gln) | G | T | A | This study | |||

| SHV-49 | AAAAAT | A (Ile) | This study | ||||||

TABLE 3.

Kinetic parameters of purified β-lactamase SHV-49a

| Substrate | SHV-49

|

SHV-1

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (mM−1 · s−1) | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (mM−1 · s−1) | |

| Benzylpenicillin | 120 | 18 | 6,700 | 455 | 20 | 23,000 |

| Amoxicillin | 250 | 470 | 530 | 900 | 90 | 10,000 |

| Ticarcillin | 1,200 | 230 | 5,200 | 60 | 22 | 2,700 |

| Piperacillin | 23 | 7 | 3,300 | 570 | 60 | 10,000 |

| Cephaloridine | 6 | 270 | 22 | 170 | 110 | 1,500 |

| Cefotaxime | <0.01 | ND | ND | NH | ND | ND |

| Ceftazidime | <0.01 | ND | ND | NH | ND | ND |

| Cefepime | <0.01 | ND | ND | >100 | >3,000 | >35 |

| Imipenem | <0.01 | ND | ND | NH | ND | ND |

NH, not hydrolyzed; ND, not determinable due to a too low initial rate of hydrolysis. The specific activity, measured with 100 μM benzylpenicillin as substrate, was 200 U per mg of proteins, with a 200-fold purification factor (22). Its purity was estimated to be >95% by SDS-PAGE analysis. The kinetic measurements of the purified SHV-49 were carried out at 30°C in 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) as previously described (23). Km and kcat values were determined by analyzing the β-lactam hydrolysis under initial rate conditions using the Eadie-Hoffstee linearization of the Michaelis-Menten equation.

The nucleotide sequence of the penicillinase-encoding gene corresponded to that of an SHV-11 variant, characterized by the Leu→Gln substitution at position 35 (1, 18), but differed from that of the blaSHV-11 gene initially described for a K. pneumoniae strain (undetermined genetic location) (18) by four silent mutations: CAC to CAT (His-112), previously reported within a self-transferable plasmid of a Shigella dysenteriae strain (1), GAT to GAC (Asp-176), GAA to GAG (Glu-240), and ACC to ACG (Thr-268) (Table 2). MICs of β-lactams for E. coli TOP10(pE1) indicated that SHV-11 did not confer oxyminocephalosporin resistance, in agreement with the first report (18) but in contrast with the second study (1). Nevertheless, the strength of the promoter markedly influences the resistance level. The −35 TTGATT and −10 ACAAAT regions upstream from blaSHV-11 in plasmid pE1 are expected to promote a lower level of gene transcription than the −35 TTGATT and −10 AAAAAT regions upstream from blaSHV-49 in pH2 (25). This feature probably explains why the penicillin MICs for E. coli TOP10(pE1) were much lower than those for E. coli TOP10(pH2) despite the decreased affinity of SHV-49 for these substrates.

Analysis of the flanking regions (ca. 400 bp) upstream and downstream from the blaSHV genes in plasmids pE1 and pH2 revealed more than 98% identity between them and with the previously sequenced homologous regions of plasmid- or chromosomally located blaSHV genes (10, 20, 25; see also GenBank accession nos. AF096930 and AF550679). The blaSHV-11 and blaSHV-49 sequences in Kp238 differed by as much as five nucleotide changes, strongly suggesting that the latter was not generated by a duplication of the former. Allelic variation in the chromosomal β-lactamase has been documented in K. pneumoniae (8, 25) as in other bacterial species. Thus, in Kp238, blaSHV-11 might be an allelic form of the K. pneumoniae chromosomal penicillinase, whereas blaSHV-49 might result from the chromosomal integration of a plasmid carrying this IRT-encoding gene and the other resistance markers of the strain. Alternatively, blaSHV-49 that exhibits a single mutation compared to the reference sequence (7) might be the species-specific enzyme derivative, while blaSHV-11 might have been provided by plasmid insertion. The origin of the plasmid-mediated SHV enzymes, i.e., the event responsible for the translocation of the species-specific blaSHV gene from the K. pneumoniae chromosome to plasmids, probably involves insertion sequences located distantly from the blaSHV genes, as suggested by unpublished sequence data (GenBank accession no. AF550679).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers. The nucleotide sequences of the blaSHV genes reported in this work are available in the GenBank nucleotide database under the accession numbers AY528717 and AY528718).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Ministère de l'Education Nationale et de la Recherche (EA-525), Université de Bordeaux 2, Bordeaux, France.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahamed, J., and M. Kundu. 1999. Molecular characterization of the SHV-11 β-lactamase of Shigella dysenteriae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2081-2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambler, R. P., A. F. Coulson, J. M. Frere, J. M. Ghuysen, B. Joris, M. Forsman, R. C. Levesque, G. Tiraby, and S. G. Waley. 1991. A standard numbering scheme for the class A β-lactamases. Biochem. J. 276:269-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bermudes, H., F. Jude, C. Arpin, C. Quentin, A. Morand, R. Labia, J. Lemozy, D. Sirot, C. Chanal, C. Huc, H. Dabernat, and J. Sirot. 1997. Characterization of an inhibitor-resistant TEM (IRT) β-lactamase in a novel strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnboim, H. C., and J. Doly. 1979. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 7:1513-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blazquez, J., M.-R. Baquero, R. Canton, I. Alos, and F. Baquero. 1993. Characterization of a new TEM-type β-lactamase resistant to clavulanate, sulbactam, and tazobactam in a clinical isolate of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:2059-2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonomo, R. A., C. G. Dawes, J. R. Knox, and D. M. Shlaes. 1995. Complementary roles of mutations at positions 69 and 242 in a class A β-lactamase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1247:113-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford, P. A. 1999. Automated thermal cycling is superior to traditional methods for nucleotide sequencing of blaSHV genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2960-2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaves, J., M. G. Ladona, C. Segura, A. Coira, R. Reig, and C. Ampurdanes. 2001. SHV-1 β-lactamase is mainly a chromosomally encoded species-specific enzyme in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2856-2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubois, V., L. Poirel, C. Marie, C. Arpin, P. Nordmann, and C. Quentin. 2002. Molecular characterization of a novel class 1 integron containing blaGES-1 and a fused product of aac3-Ib/aac6′-Ib′ gene cassettes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:638-645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fortineau, N., T. Naas, O. Gaillot, and P. Nordmann. 2001. SHV-type extended-spectrum β-lactamase in a Shigella flexneri clinical isolate. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:685-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Girlich, D., A. Karim, L. Poirel, M. H. Cavin, C. Verny, and P. Nordmann. 2000. Molecular epidemiology of an outbreak due to IRT-2 β-lactamase-producing strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae in a geriatric department. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45:467-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helfand, M. S., A. M. Hujer, F. D. Sonnichsen, and R. A. Bonomo. 2002. Unexpected advanced generation cephalosporinase activity of the M69F variant of SHV β-lactamase. J. Biol. Chem. 277:47719-47723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henquell, C., C. Chanal, D. Sirot, R. Labia, and J. Sirot. 1995. Molecular characterization of nine different types of mutants among 107 inhibitor-resistant TEM β-lactamases from clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:427-430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarlier, V., and P. Nordmann. 2000. Sensibilité aux antibiotiques: entérobactéries et β-lactamines, p. 649-665. In J. Freney, F. Renaud, W. Hansen, and C. Bollet (ed.), Précis de bactériologie clinique. ESKA, Paris, France.

- 15.Leflon-Guibout, V., V. Speldooren, B. Heym, and M. Nicolas-Chanoine. 2000. Epidemiological survey of amoxicillin-clavulanate resistance and corresponding molecular mechanisms in Escherichia coli isolates in France: new genetic features of blaTEM genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2709-2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemozy, J., D. Sirot, C. Chanal, C. Huc, R. Labia, H. Dabernat, and J. Sirot. 1995. First characterization of inhibitor-resistant TEM (IRT) β-lactamases in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2580-2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthew, M., A. M. Harris, M. J. Marshall, and G. W. Ross. 1975. The use of analytical isoelectric focusing for detection and identification of β-lactamases. J. Gen. Microbiol. 88:169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nüesch-Inderbinen, M. T., F. H. Kayser, and H. Hächler. 1997. Survey and molecular genetics of SHV β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae in Switzerland: two novel enzymes, SHV-11 and SHV-12. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:943-949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petit, A., H. Ben Yaghlane-Bouslama, L. Sofer, and R. Labia. 1992. Does high level production of SHV-type penicillinase confer resistance to ceftazidime in Enterobacteriaceae? FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 71:89-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Podbielski, A., and B. Melzer. 1990. Nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding the SHV-2 β-lactamase (blaSHV-2) of Klebsiella ozaenae. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:4916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Podschun, R., and U. Ullmann. 1998. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:589-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poirel, L., M. Guibert, D. Girlich, T. Naas, and P. Nordmann. 1999. Cloning, sequence analyses, expression, and distribution of ampC-ampR from Morganella morganii clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:769-776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poirel, L., C. Heritier, I. Podglajen, W. Sougakoff, L. Gutmann, and P. Nordmann. 2003. Emergence in Klebsiella pneumoniae of a chromosome-encoded SHV β-lactamase that compromises the efficacy of imipenem. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:755-758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prinarakis, E. E., V. Miriagou, E. Tzelepi, M. Gazouli, and L. S. Tzouvelekis. 1997. Emergence of an inhibitor-resistant β-lactamase (SHV-10) derived from an SHV-5 variant. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:838-840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rice, L. B., L. L. Carias, A. M. Hujer, M. Bonafede, R. Hutton, C. Hoyen, and R. A. Bonomo. 2000. High-level expression of chromosomally encoded SHV-1 β-lactamase and an outer membrane protein change confer resistance to ceftazidime and piperacillin-tazobactam in a clinical isolate of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:362-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 27.Stapleton, P., P. J. Wu, A. King, K. Shannon, G. French, and I. Phillips. 1995. Incidence and mechanisms of resistance to the combination of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2478-2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]