Abstract

Mycobacteria contain an outer membrane of unusually low permeability which contributes to their intrinsic resistance to many agents. It is assumed that small and hydrophilic antibiotics cross the outer membrane via porins, whereas hydrophobic antibiotics may diffuse through the membrane directly. A mutant of Mycobacterium smegmatis lacking the major porin MspA was used to examine the role of the porin pathway in antibiotic sensitivity. Deletion of the mspA gene caused high-level resistance of M. smegmatis to 256 μg of ampicillin/ml by increasing the MIC 16-fold. The permeation of cephaloridine in the mspA mutant was reduced ninefold, and the resistance increased eightfold. This established a clear relationship between the activity and the outer membrane permeation of cephaloridine. Surprisingly, the MICs of the large and/or hydrophobic antibiotics vancomycin, erythromycin, and rifampin for the mspA mutant were increased 2- to 10-fold. This is in contrast to those for Escherichia coli, whose sensitivity to these agents was not affected by deletion of porin genes. Uptake of the very hydrophobic steroid chenodeoxycholate by the mspA mutant was retarded threefold, which supports the hypothesis that loss of MspA indirectly reduces the permeability by the lipid pathway. The multidrug resistance of the mspA mutant highlights the prominent role of outer membrane permeability for the sensitivity of M. smegmatis to antibiotics. An understanding of the pathways across the outer membrane is essential to the successful design of chemotherapeutic agents with activities against mycobacteria.

The prevalence and spread of antibiotic resistance are increasingly serious problems that hamper the effective treatment of infectious diseases (26). The search for new antibiotics is mainly based on novel bacterial targets and high-throughput screening assays (10). However, many lead compounds discovered in vitro may fail because they do not reach their targets at sufficiently high concentrations in vivo (7). This is true in particular for gram-negative bacteria, which, in contrast to gram-positive bacteria, are protected from the toxic actions of certain antibiotics, dyes, and detergents and host defense factors such as lysozyme by an additional outer membrane (OM) (49). The OM can be crossed by at least two general pathways: the hydrophobic (or lipid) pathway, which is characterized by the nature and the interactions of the membrane lipids, and the hydrophilic (or porin) pathway, whose properties are determined by water-filled channel proteins, the porins, which span the OM of gram-negative bacteria (49). It has been shown by the pioneering work of Nikaido and collaborators (21, 46) that Escherichia coli and Salmonella porins play a major role in the transport of β-lactam antibiotics. Subsequent studies showed that porin-deficient mutants of gram-negative bacteria were also more resistant to quinolones, tetracyclines, chloramphenicol, nalidixic acid, and trimethoprim (6, 15, 25, 52). These data suggest that porins are involved in the transport of these antibiotics, but the levels of resistance were rather low, as reflected by the 1.5- to 4-fold increased MICs for the porin mutants. However, combination of low-level OM permeability with drug efflux produces high-level resistance in gram-negative bacteria (44, 45) and is a powerful mechanism leading to multidrug resistance (51).

The permeability of the cell envelope of mycobacteria is several orders of magnitude lower than that of the cell envelope of gram-negative bacteria, which is believed to be the major reason for the intrinsic resistance of mycobacteria to most antibiotics and chemotherapeutic agents (31). This is likely due to an unique arrangement of the longest fatty acids known to date in nature, the mycolic acids, which can consist of up to 90 carbon atoms and which are covalently bound to a single polymeric head group, the arabinogalactan (4). Porins in the mycobacterial OM mediate the diffusion of hydrophilic solutes, although the efficiency of this pathway is 100- to 1,000-fold lower than that in E. coli (32). The porin MspA was identified in CHCl3-methanol and in detergent extracts of Mycobacterium smegmatis (24, 41). Expression of the mspA gene encoding the mature MspA protein in E. coli yielded a folded but inactive 20-kDa monomer (23) and an oligomer with an apparent molecular mass of 100 kDa, which formed channels similar to those of the native protein (41). The genome of M. smegmatis encodes three additional very similar porins, designated MspB, MspC, and MspD, that differ from MspA only at 2, 4, and 18 positions of the mature protein, respectively (61). Detergent extracts of a ΔmspA M. smegmatis mutant exhibited significantly lower channel activities in lipid bilayer experiments and contained fewer porins than extracts of wild-type M. smegmatis. The lower porin content reduced the cell wall permeability of the ΔmspA mutant for cephaloridine and glucose nine- and fourfold, respectively. However, the growth rate was not significantly altered upon deletion of the mspA gene (61). These results show that MspA is the main general diffusion pathway for hydrophilic molecules across the OM of M. smegmatis and is only partially replaced by fewer porins in the cell wall of the ΔmspA mutant. Other fast-growing mycobacteria, such as M. chelonae and M. phlei, appear to encode porins similar to MspA (41, 54), but no sequence homologs were identified in slowly growing mycobacteria, such as M. tuberculosis, or in any other organism outside the genus Mycobacterium (40). Determinants of the low efficiency of the porin pathway in M. smegmatis are the 45-fold lower number of pores and the 2.5-fold longer pore channels compared to the numbers and the sizes of the pores in E. coli (12). Similar causes for low permeability are likely to exist for all mycobacteria (40). However, the relative importance of the porin pathway and the lipid pathway across the OM of mycobacteria is unknown for any antibiotic, although the synergistic effects of cell wall-damaging agents such as ethambutol with many other drugs have been known for a long time (22, 67).

To examine the role of porins in the antibiotic sensitivity of M. smegmatis, we determined the MICs of many antibiotics for an M. smegmatis mspA mutant. Furthermore, we did transport experiments using radiolabeled compounds to confirm that reduced sensitivity correlated with slower uptake. This study demonstrates for the first time the importance of porins for the sensitivity of M. smegmatis to both hydrophilic and hydrophobic antibiotics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals, bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

Chemicals were purchased from Merck, Roth, or Sigma at the highest purity available. [14C]chenodeoxycholate was obtained from NEN Life Science Products, and [14C]isoniazid was obtained from Hartmann Analytic. M. smegmatis SMR5 is a derivative of M. smegmatis mc2155 and is streptomycin resistant due to a mutation in ribosomal protein S12 (55). The construction of ΔmspA mutant M. smegmatis MN01 was described previously (61). All mycobacterial strains were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 liquid medium (Difco) supplemented with 0.2% glycerol and 0.05% Tween 80 or on Middlebrook 7H10 plates (Difco) containing 0.2% glycerol at 37°C.

Drug sensitivity by agar dilution.

The MICs for M. smegmatis SMR5 and M. smegmatis MN01 were determined in triplicate by serial dilutions in 7H10 agar. Each strain was first grown in a 4-ml culture for 2 days at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6 to 0.8. The cultures were diluted with 7H9 liquid medium to yield approximately 5,000 CFU per ml. Approximately 500 CFU was streaked on plates containing the appropriate antibiotic concentrations. As a reference, 500 CFU was also streaked on plates without antibiotic. The number of surviving cells was normalized to the number of cells counted on plates without antibiotic for each strain and was expressed as the relative CFU (percent CFU). For all drugs tested, the concentration that resulted in the complete inhibition of bacterial growth after 3 days of incubation at 37°C was determined as the MIC of the drug.

Transport experiments.

Transport experiments were carried out as described previously (61). To reduce aggregation and clumping of the cells, M. smegmatis SMR5 and MN01 were each first grown in 4-ml cultures for 2 days at 37°C and then filtered through a 5-μm-pore-size filter (Sartorius). The filtrates were grown for 2 days at 37°C and then used to inoculate 100-ml cultures, which were grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (1,250 × g at 4°C for 10 min), washed once in 2 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (pH 6.5)-0.05 mM MgCl2, and resuspended in the same buffer. The 14C-labeled compounds and their nonlabeled analogs were mixed and added to the cell suspensions to obtain final concentrations of 5 and 20 μM. The mixtures were incubated at 37°C, and 1-ml samples were removed at the indicated times. The cells were filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter (Sartorius), washed with 0.1 M LiCl, and counted in a liquid scintillation counter. The mean dry weight of the cells in these samples was 1.4 ± 0.4 mg. The uptake rate was expressed as nanomoles per milligram of cells.

Analysis of cell wall lipids of M. smegmatis.

M. smegmatis mc2155 and its isogenic porin-deficient mutant strain, MN01, were grown as surface pellicles on Sauton's medium for 6 days at 37°C. The strains were maintained by selection with streptomycin, which was added to a final concentration of 20 μg/ml. Lipids were isolated and characterized as described previously (13). Wet cells were first extracted with chloroform-methanol (1:2; vol/vol), then five times with chloroform-methanol (1:1; vol/vol), and finally, once with chloroform-methanol (2:1; vol/vol). These extracts were pooled, dried under vacuum, and partitioned between water and chloroform (1:1; vol/vol). The organic phase was extensively washed with distilled water, evaporated to dryness to yield the crude lipid extract, and weighed. Cell-bound fatty acids (mycolates) were obtained by saponification of delipidated cells with 5% KOH in methanol-benzene (8:2; vol/vol) for 16 h at 80°C. After acidification with sulfuric acid, fatty acids were extracted with diethyl ether and extensively washed with water. The washed lipid extract was dissolved in chloroform and analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on silica gel plates (thickness, 0.25 mm; Macheray-Nagel) precoated with Durasil 25. Lipid spots were resolved by TLC run in the following solvent mixtures: petroleum ether-diethyl ether (9:1; vol/vol) for analysis of triacyl glycerols (TAGs), chloroform-methanol (9:1; vol/vol) for analysis of glycopeptidolipids (GPLs) and trehalose dimycolates (TDMs), and chloroform-methanol-water (60:30:8; vol/vol) for analysis of trehalose monomycolates (TMMs) and phospholipids. Sugar-containing compounds (GPLs, TDMs, TMMs and phosphatidylinositol mannosides) were visualized by spraying the plates with 0.2% anthrone in concentrated sulfuric acid, followed by heating at 110°C. The Dittmer-Lester reagent (9) was used to detect phosphorus-containing substances. The ninhydrin reagent was used to reveal the presence of free amino groups. A spray with 10% molybdophosphoric acid in ethanol solution, followed by heating at 110°C, was used to detect all of the lipids spots, including TAGs.

RESULTS

The mspA mutant of M. smegmatis is more resistant to most β-lactam antibiotics.

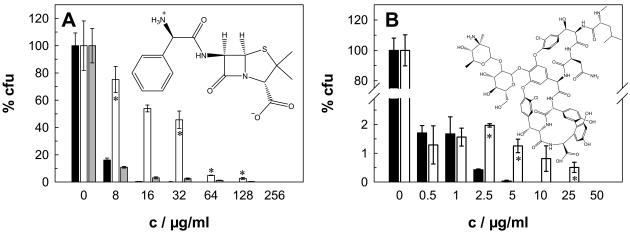

It has been well established that β-lactam antibiotics cross the OM of gram-negative bacteria by diffusing through porin channels (29, 48, 56). Therefore, we first examined whether deletion of the major porin MspA of M. smegmatis has any influence on the resistance of mycobacteria to β-lactam antibiotics. MICs were determined by agar dilution with Middlebrook 7H10 plates. Figure 1A shows that wild-type strain M. smegmatis SMR5 is drastically more susceptible to the zwitterionic agent ampicillin than the isogenic mspA mutant strain, M. smegmatis MN01. Thus, deletion of mspA increased the ampicillin MIC for M. smegmatis by 16-fold, to 256 μg/ml (Table 1). Expression of the mspA gene on a plasmid (pMN014) in M. smegmatis MN01 established again the sensitivity of the wild type, demonstrating that the loss of mspA caused the resistance phenotype. M. smegmatis was also more sensitive to the zwitterionic agent cephaloridine than to ampicillin. Deletion of the mspA gene increased the cephaloridine MIC fourfold (Table 1). No significant difference in the susceptibilities of the two strains to the anionic agent cephalothin was observed (Table 1). It should be noted that the growth rates of both strains are similar in standard 7H9 and minimal liquid media (61) and on 7H10 agar plates.

FIG. 1.

MspA-dependent sensitivity of M. smegmatis to hydrophilic antibiotics. The sensitivities of wild-type M. smegmatis (black bars), the ΔmspA mutant (white bars), and the ΔmspA mutant transformed with the mspA expression vector pMN014 (gray bars) to ampicillin (A) and vancomycin (B) were determined by serial dilution in Middlebrook 7H10 agar. The number of surviving cells was normalized to the number cells counted on plates without antibiotic for each strain, and the results are expressed as relative CFU (percent CFU). The sensitivity experiments were done in triplicate, and the concentrations (c) are shown with their standard deviations. The structures of the antibiotics are shown in the corresponding graphs. The asterisks denote the datum points that differed significantly (P < 0.05) between the wild-type strain and the mspA mutant strain by the paired Student t test.

TABLE 1.

Physicochemical properties of antibiotics and the efficiencies of their activities against M. smegmatisa

| Antibiotic | Molecular mass (g/mol) | Partition coefficient (Pow) | MIC (μg/ml) for M. smegmatis

|

R factor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | ΔmspA | ||||

| Ampicillin | 349 | 0.002-0.2 (pH 7.2)b,<0.01 (pH 7.0)c | 16 | 256 | 16 |

| Cephaloridine | 416 | 0.02-0.03 (pH 7.4)b | 16 | 128 | 8 |

| Cephalothin | 395 | 0.006-3.6 (pH 7.4)b,<0.01 (pH 7.0)c | 250 | 500 | 2 |

| Kanamycin A | 488 | NFd | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Vancomycin | 1486 | <0.01 (pH 7.0)c | 5 | 50 | 10 |

| d-Cycloserine | 102 | <0.01 (pH 7.0)c | 125 | 150 | 1.2 |

| Ethambutol | 204 | NF | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Isoniazid | 137 | 0.07 (pH 7.4)b | >40 | >40 | 1 |

| Tetracyclin | 444 | 0.04-0.07 (pH 7.0)b,c | 0.2 | 0.25 | 1.25 |

| Chloramphenicol | 323 | 12.3-12.4 (pH 7.0)b,c | 16 | 32 | 2 |

| Erythromycin A | 734 | 4.6-18.2 (pH 7.4)b | 128 | >256 | 2 |

| Novobiocin | 613 | 5.2-38.0 (pH 7.4)b, >20 (pH 7.0)c | 25 | 25 | 1 |

| Rifampin | 821 | 20.9 (pH 7.5)b | 25 | 75 | 3 |

The molecular masses of the antibiotics, their hydrophobicities as apparent n-octanol-water partition coefficients (Pow), and their MICs for M. smegmatis SMR5 (wild type) and mutant strain MN01 (ΔmspA) are listed. Apparent n-octanol-water partition coefficients were determined in triplicate and are shown with their standard deviations. The resistance (R) factor for M. smegmatis is given by the ratio of the MIC for ΔmspA mutant/MIC for the wild type.

Data are from reference 20.

Data are from reference 42.

NF, not found.

The susceptibility of M. smegmatis to vancomycin but not to aminoglycosides is affected by deletion of the mspA gene.

Hydrophilic solutes up to an exclusion limit of approximately 600 to 700 Da are thought to prefer the porin pathway across the OM of gram-negative bacteria (43). Since the exclusion limit of mycobacterial porins for hydrophilic solutes is unknown, we examined whether the susceptibility of M. smegmatis to hydrophilic antibiotics larger than β-lactam antibiotics was also affected by deletion of the mspA gene. The susceptibility of M. smegmatis to kanamycin was high, and that of the mspA mutant was increased only slightly (data not shown). This result is similar to that obtained for porin mutants of E. coli, which did not show altered susceptibilities to aminoglycoside antibiotics (16, 18). Surprisingly, the mspA mutant was clearly more resistant to the much larger hydrophilic peptide antibiotic vancomycin (Fig. 1B). This result was also reflected by a 10-fold increased MIC (Table 1). It should be noted that only a small population of vancomycin-resistant cells caused the increased MIC for the mspA mutant (Fig. 1B) and that M. smegmatis was 50-fold more sensitive to vancomycin than E. coli (64).

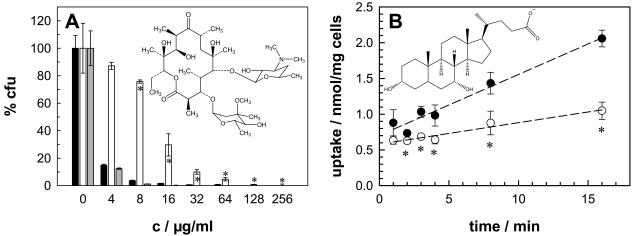

The mspA mutant of M. smegmatis is more resistant to hydrophobic antibiotics.

The rates of penetration of compounds through water-filled protein channels such as the porins decrease with increasing hydrophobicity (46). This explains why E. coli mutants lacking one or more porins have nearly unaltered sensitivities to hydrophobic antibiotics (49). A similar behavior was expected for porin mutants of M. smegmatis. Surprisingly, deletion of the mspA gene increased the resistance of M. smegmatis to the hydrophobic antibiotic erythromycin, resulting in a more than twofold increased MIC (Fig. 2A; Table 1). The level of resistance mediated by the loss of MspA was even more pronounced than that obtained for the hydrophilic antibiotic cephaloridine, although this is not reflected in the MICs of the two antibiotics (Table 1). The susceptibility of the mutant to erythromycin was restored by expression of the mspA gene (Fig. 2A), demonstrating that deletion of the mspA gene caused this resistance phenotype. The sensitivities of M. smegmatis MN01 to rifampin, novobiocin, and chloramphenicol were determined to examine whether deletion of mspA also affected sensitivities to other hydrophobic compounds or was an erythromycin-specific effect. Rifampin was less effective against M. smegmatis MN01 than against the wild type (Table 1). Similarly, the hydrophobic antibiotics novobiocin and chloramphenicol were less effective against the mspA mutant, although the difference was smaller that that for erythromycin and was detectable at only a few concentrations (data not shown). These results indicate that the reduced porin expression increased the level of resistance of the mspA mutant not only to hydrophilic antibiotics but also to hydrophobic antibiotics.

FIG. 2.

MspA-dependent sensitivities and permeabilities of M. smegmatis to hydrophobic compounds. (A) The sensitivities of wild-type M. smegmatis (black bars), the ΔmspA mutant (white bars), and the ΔmspA mutant transformed with the mspA expression vector pMN014 (gray bars) to erythromycin were determined by serial dilution in Middlebrook 7H10 agar (c, concentration). The number of surviving cells was normalized to the number of cells counted on plates without antibiotic for each strain, and the results are expressed as relative CFU (percent CFU). (B) The accumulation of [14C]chenodeoxycholate by M. smegmatis SMR5 (wild type; closed circles) and M. smegmatis MN01 (ΔmspA; open circles) was measured. Regression analysis yielded uptake rates of 0.09 and 0.03 nmol mg−1 min−1 for 20 μM chenodeoxycholate for the wild-type and mutant strains of M. smegmatis, respectively. The assay was performed at 37°C. The structures of the compounds are shown in the corresponding graphs. The sensitivity and uptake experiments were done in triplicate, and the results are shown with their standard deviations. The asterisks denote the datum points that differed significantly (P < 0.05) between the wild-type strain and the mspA mutant strain by the paired Student t test.

Considering the reduced susceptibility of the M. smegmatis mspA mutant to hydrophobic antibiotics, we suspected that a less efficient permeation of hydrophobic solutes might be responsible for this phenotype. To this end, we measured the rates of uptake of the very hydrophobic steroid chenodeoxycholate, which is considered an indicator of the permeability of the lipid pathway in mycobacteria, by M. smegmatis and the mspA mutant (28, 36). The uptake rate was 0.09 nmol · min−1 · mg−1 for the wild type, but the rate was reduced threefold for the mspA mutant (Fig. 2B). This result indicates that, indeed, a slower rate of transport of hydrophobic compounds across the OM increased the level of resistance of the mspA mutant to hydrophobic antibiotics.

Quantitative analysis of the cell wall lipids of the M. smegmatis wild type and the ΔmspA strain.

Alteration of the lipid composition of the cell wall of M. smegmatis might explain the decreased permeability of the ΔmspA mutant to hydrophobic compounds. To test this possibility, noncovalently bound lipids of the cell wall of the M. smegmatis wild type and the ΔmspA mutant were extracted with organic solvents and analyzed by TLC. The cell-bound fatty acids (mycolates) were obtained by saponification of the delipidated cells and extraction with ether oxide. The following lipids were detected in similar amounts in both strains of M. smegmatis: TAGs, GPLs, TDM, TMM, phosphatidylinositol mannosides 2 and 6, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylglycerol, and phosphatidylethanolamine. These results show that deletion of the porin gene mspA does not significantly alter the lipid composition of the M. smegmatis cell wall.

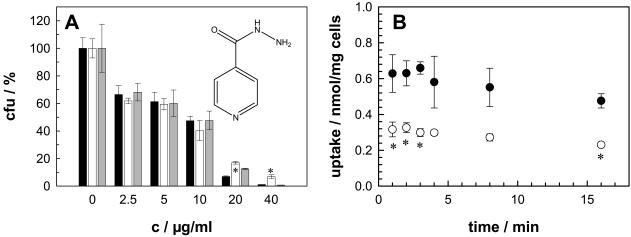

Deletion of the mspA gene does not affect the susceptibility of M. smegmatis to small and hydrophilic chemotherapeutic agents for tuberculosis.

Mycolic acids and arabinogalactan are essential components of the mycobacterial cell wall. Isoniazid and ethambutol interfere with the synthesis of mycolic acids (65) and with the assembly and synthesis of the arabinogalactan (62), respectively. Both drugs are essential in present tuberculosis chemotherapy regimens (34). Since isoniazid and ethambutol are small and hydrophilic molecules, it was assumed that they use the porin pathway for entry into mycobacteria (35). Similar considerations apply to cycloserine, which inhibits peptidoglycan synthesis and which is used as a second-line drug in tuberculosis chemotherapy. Despite these assumptions, the effect of deletion of the mspA gene on the sensitivity of M. smegmatis to these drugs was negligible. The mspA mutant showed marginally increased levels of resistance to all three drugs only at high concentrations. This is shown for isoniazid in Fig. 3A . Interpretation of the results of drug sensitivity experiments in terms of cell wall permeability is always difficult and might be additionally hampered for isoniazid, because M. smegmatis is naturally about 100-fold more resistant to isoniazid than M. tuberculosis (66). Therefore, we examined the transport of 20 μM [14C]isoniazid directly. The amount of isoniazid associated with wild-type M. smegmatis was significantly higher than that associated with the mspA mutant, but it did not increase between 1 and 15 min for both strains in several independent experiments at 37°C (Fig. 3B), indicating that an equilibrium was already reached in these experiments. To slow the uptake rate, the concentration of isoniazid was reduced to 5 μM and the experiments were performed at 20°C. Again, more isoniazid was associated with wild-type M. smegmatis than with the mspA mutant, but no significant uptake was observed at between 15 and 90 s after addition of isoniazid to the cell suspensions (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

MspA-dependent sensitivity and permeability of M. smegmatis to isoniazid. (A) The sensitivities of wild-type M. smegmatis (black bars), the ΔmspA mutant (white bars), and the ΔmspA mutant transformed with the mspA expression vector pMN014 (gray bars) to isoniazid were determined by serial dilution in Middlebrook 7H10 agar (c, concentration). The number of surviving cells was normalized to the number of cells counted on plates without antibiotic for each strain, and the results are expressed as relative CFU (percent CFU). The structure of isoniazid is shown. (B) The accumulation of 20 μM [14C]isoniazid by M. smegmatis SMR5 (wild type; closed circles) and M. smegmatis MN01 (ΔmspA; open circles) was measured. The assay was performed at 37°C. The sensitivity and uptake experiments were done in triplicate, and the results are shown with their standard deviations. The asterisks denote the datum points that differed significantly (P < 0.05) between the wild-type strain and the mspA mutant strain by the paired Student t test.

DISCUSSION

The intrinsic resistance of mycobacteria to most antibiotics and chemotherapeutic agents is believed to be a result of their impermeable OM in synergy with other resistance mechanisms, such as enzymatic inactivation or active efflux of the drugs (4, 31). The role of the porin pathway across the OM in the sensitivity of M. smegmatis to antibiotics was examined by using a mutant of M. smegmatis lacking the main porin MspA. The MIC of cephaloridine for this mutant increased eightfold, and the OM of the mutant had a ninefold reduced permeability to cephaloridine, while the β-lactamase activity of M. smegmatis was not altered (61). Thus, slower uptake of cephaloridine is directly correlated with increased resistance. These results indicate further that cephaloridine mainly diffuses through the MspA channel across the OM of M. smegmatis. Similar conclusions were drawn for E. coli, in which the outstanding permeation of cephaloridine through the porin OmpF was paralleled by its strong activity (46). However, it should be noted that there are two major differences between M. smegmatis and E. coli. First, M. smegmatis is about eight-fold less sensitive to cephaloridine than E. coli (MIC = 2 μg/ml) (21), consistent with a less permeable OM. Second, deletion of the porin gene mspA clearly increased the level of resistance of M. smegmatis to cephaloridine in contrast to that of E. coli, for which inactivation of the OmpF porin did not detectably alter the cephaloridine MIC (21, 29). The cephaloridine MIC for the mspA mutant was even higher than that for an E. coli mutant lacking both major porins, OmpC and OmpF (29). Deletion of mspA produced high-level resistance of M. smegmatis to ampicillin by increasing the MIC 16-fold (MIC = 256 μg/ml). This is the largest increase in the MIC of an antibiotic ever observed for a single-porin-knockout strain, in which no or only small effects of gene knockouts on drug sensitivity are usually shown (21). Such a high level of resistance to ampicillin was not observed even when the two main porins of E. coli, OmpF and OmpC, were inactivated (29), underlining the importance of MspA for sensitivity to ampicillin. M. smegmatis was resistant to a 15-fold higher concentration of the monoanionic agent cephalothin (Table 1), consistent with the 10-fold lower OM permeability of cephalothin compared to that of the zwitterionic agent cephaloridine (63). The cephalothin MIC for the mspA mutant was increased only slightly, indicating that negative charges severely hamper diffusion through MspA. This is explained by the crystal structure of MspA, which shows two rings, each of which has eight aspartate residues, lining the channel at the constriction zone (14). Thus, penetration of cephalothin through a nonporin pathway may be significant, consistent with observations for other β-lactam antibiotics, which have low rates of diffusion through E. coli porins (47). Taken together, these results indicate that hydrophilic and cationic or zwitterionic β-lactam antibiotics cross the OM of M. smegmatis via the porin pathway, similar to the situation in E. coli, in which most β-lactams were found to diffuse through porins (46, 47).

Isoniazid and ethambutol are small and hydrophilic drugs indispensable in present tuberculosis chemotherapy regimens (34) and are thought to penetrate the mycobacterial cell via porins (35). The same holds true for the second-line antituberculosis drug cycloserine. We observed an increased level of resistance of the mspA mutant to these drugs only at concentrations close to the MIC (Fig. 3A). Since small and hydrophilic molecules diffuse through porins very fast, permeation through the remaining porins of the mspA mutant, MspB, MspC, and MspD, might still be sufficient for these drugs to inactivate their target enzymes at similar rates in both strains. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that MspA does not contribute to the uptake of these drugs. We also could not measure any isoniazid uptake for M. smegmatis between 15 s and 15 min, in contrast to the uptake results in experiments with M. tuberculosis (3). Whether this is due to a faster drug efflux in M. smegmatis or to other mechanisms is not known.

The kanamycin MIC for the mspA mutant of M. smegmatis was not reduced. This is similar to the findings for E. coli porin mutants (18). These results could be explained by a very efficient diffusion of aminoglycosides through the remaining porins in the mutants, as suggested earlier for E. coli on the basis of liposome swelling experiments (39). An alternative route of cell entry for aminoglycosides was proposed for Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which has an exceptionally low permeability by the porin pathway (17). Aminoglycosides were shown to permeabilize the OM of P. aeruginosa (19) and E. coli (18) and thereby promote their own uptake. Self-promoted uptake may be significant for M. smegmatis when the even lower porin-mediated OM permeability in M. smegmatis compared to that in P. aeruginosa is considered (30) and might explain the unchanged sensitivity of the mspA mutant of M. smegmatis to kanamycin.

Surprisingly, the vancomycin MIC for the mspA mutant was increased 10-fold. It has been shown that OM proteins with large channels, such as TolC, which has a channel diameter of 3.5 nm and which translocates folded polypeptides across the OM of E. coli (33), or the phage export channel protein pIV (38), are needed to promote vancomycin uptake in E. coli. However, the crystal structure of MspA revealed a channel constriction with a diameter of 1 nm (14), which is too small to allow passage of vancomycin, which has molecular dimensions of 2.9 by 2.4 nm (57). Thus, it appears very unlikely that vancomycin can diffuse through the MspA channel. It should be noted that only a few percent of wild-type and mspA mutant cells were resistant to vancomycin at concentrations of 0.5 μg/ml or higher, indicating that the majority of the cells of both strains were killed at concentrations far below the MIC (Fig. 1B). This is reminiscent to the observation of “heteroresistant staphylococci,” in which the majority of a Staphylococcus aureus population is vancomycin susceptible and a minority population is vancomycin resistant (60). Deletion of mspA apparently increased the MIC for the resistant subpopulation of M. smegmatis. A thickened cell wall has been shown to be associated with vancomycin resistance in staphylococci (8). In the genus Enterococcus, resistance to vancomycin relies on the exchange of the terminal dipeptide in pentapeptide cell wall precursors (2). However, the molecular mechanisms of vancomycin resistance in mycobacteria are unknown.

The hyperresistance of the mspA mutant of M. smegmatis to the large hydrophobic antibiotics rifampin and erythromycin was unexpected for two reasons. First, the rates of diffusion of β-lactam antibiotics through the porins of E. coli inversely depend on their hydrophobicities and are correlated with their efficacies (48). This was consistent with the observations that the sensitivities of E. coli and other gram-negative bacteria to hydrophobic antibiotics were not affected by the deletion of porins (49, 56) but were increased by mutation of the lipopolysaccharide or damage to the OM (42, 49). The highly negatively charged constriction site of the MspA channel (14) likely creates shells of strongly bound water molecules which should exclude hydrophobic solutes from passage. A similar mechanism, albeit based on a very different structure, was postulated and confirmed for the porin OmpF of E. coli (27, 58). Second, in addition to being hydrophobic, the large sizes of erythromycin and rifampin make it rather unlikely that these antibiotics diffuse through the MspA pore at a significant rate. An indirect effect of MspA on the OM permeability of M. smegmatis provides an alternative explanation for the increased resistance of the mspA mutant M. smegmatis to hydrophobic antibiotics. Alteration of the permeability of the lipid pathway by deletion of MspA is supported by the finding that the rate of uptake of the very hydrophobic agent chenodeoxycholate by the mspA mutant is reduced threefold compared to that by the wild type. Decreased permeability to chenodeoxycholate was also observed in a mutant of M. tuberculosis lacking oxygenated mycolic acids (11), which shows that the lipid arrangement is important for the permeability of the mycobacterial OM. Heterologous expression of a very small number of MspA porins increased the permeability of M. tuberculosis for the nucleic acid-binding, membrane-permeant stain SYTO 9 by 10-fold, indicating that MspA has a significant influence on OM properties (37). Thus, the lipid arrangement in the mycobacterial OM appears to depend on both the mycolic acid and the protein compositions. Although this model would explain the unexpected cross-resistance of the mspA mutant of M. smegmatis to hydrophobic antibiotics, it is in contrast to observations for Salmonella, in which reduced levels of OM proteins increased the rates of penetration of hydrophobic compounds (1). Experiments probing the fluidity of the OM of porin mutants are needed to solve this apparent contradiction. Taken together, this study highlights the importance of porins for the antibiotic resistance of M. smegmatis. This is of direct medical relevance for the treatment of nosocomial infections caused by the opportunistic pathogens M. chelonae and M. fortuitum, which have Msp-like porins (41), which are prevalent in up to 90% of biofilms (59), and which are associated with wound and catheter infections (5). Since the principal structure of the cell wall appears to be similar for many mycobacteria (50), it is anticipated that porins also play a role in determining the drug sensitivity of M. tuberculosis. However, the majority of clinically relevant multidrug-resistant M. tuberculosis strains arise as a result of the sequential accumulation of resistance mutations in known genes, which either encode the targets or are involved in activation of the individual drugs. Nevertheless, M. tuberculosis strains with unknown resistance mechanisms exist for each of the primary antituberculosis drugs (53), and such strains should be analyzed for mutations involving porin genes and/or drug efflux.

Acknowledgments

We thank Susanne Kubetzko for initial help with sensitivity experiments and Wolfgang Hillen for continuous support.

This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant NI 412) and the European Union (5th Framework Programme, contract QLK2-2000-01761).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ames, G. F., E. N. Spudich, and H. Nikaido. 1974. Protein composition of the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium: effect of lipopolysaccharide mutations. J. Bacteriol. 117:406-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araoz, R., E. Anhalt, L. Rene, M. A. Badet-Denisot, P. Courvalin, and B. Badet. 2000. Mechanism-based inactivation of VanX, a d-alanyl-d-alanine dipeptidase necessary for vancomycin resistance. Biochemistry 39:15971-15979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardou, F., C. Raynaud, C. Ramos, M. A. Laneelle, and G. Laneelle. 1998. Mechanism of isoniazid uptake in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology 144:2539-2544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan, P. J., and H. Nikaido. 1995. The envelope of mycobacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64:29-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown-Elliott, B. A., and R. J. Wallace, Jr. 2002. Clinical and taxonomic status of pathogenic nonpigmented or late-pigmenting rapidly growing mycobacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:716-746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chopra, I., and S. J. Eccles. 1978. Diffusion of tetracycline across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli K-12: involvement of protein Ia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 83:550-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coates, A., Y. Hu, R. Bax, and C. Page. 2002. The future challenges facing the development of new antimicrobial drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 1:895-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui, L., X. Ma, K. Sato, K. Okuma, F. C. Tenover, E. M. Mamizuka, C. G. Gemmell, M. N. Kim, M. C. Ploy, N. El-Solh, V. Ferraz, and K. Hiramatsu. 2003. Cell wall thickening is a common feature of vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dittmer, J. C. F., and R. L. Lester. 1964. A simple specific spray for the detection of phospholipids on thin layer chromatography. J. Lipid Res. 5:126-127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donadio, S., L. Carrano, L. Brandi, S. Serina, A. Soffientini, E. Raimondi, N. Montanini, M. Sosio, and C. O. Gualerzi. 2002. Targets and assays for discovering novel antibacterial agents. J. Biotechnol. 99:175-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubnau, E., J. Chan, C. Raynaud, V. P. Mohan, M. A. Laneelle, K. Yu, A. Quemard, I. Smith, and M. Daffé. 2000. Oxygenated mycolic acids are necessary for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Mol. Microbiol. 36:630-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engelhardt, H., C. Heinz, and M. Niederweis. 2002. A tetrameric porin limits the cell wall permeability of Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Biol. Chem. 277:37567-37572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Etienne, G., C. Villeneuve, H. Billman-Jacobe, C. Astarie-Dequeker, M. A. Dupont, and M. Daffe. 2002. The impact of the absence of glycopeptidolipids on the ultrastructure, cell surface and cell wall properties, and phagocytosis of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microbiology 148:3089-3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faller, M., M. Niederweis, and G. E. Schulz. 2004. The structure of a mycobacterial outer-membrane channel. Science 303:1189-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutmann, L., R. Williamson, N. Moreau, M. D. Kitzis, E. Collatz, J. F. Acar, and F. W. Goldstein. 1985. Cross-resistance to nalidixic acid, trimethoprim, and chloramphenicol associated with alterations in outer membrane proteins of Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Serratia. J. Infect. Dis. 151:501-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hancock, R. E. 1997. The bacterial outer membrane as a drug barrier. Trends Microbiol. 5:37-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hancock, R. E., and F. S. Brinkman. 2002. Functions of Pseudomonas porins in uptake and efflux. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56:17-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hancock, R. E., S. W. Farmer, Z. S. Li, and K. Poole. 1991. Interaction of aminoglycosides with the outer membranes and purified lipopolysaccharide and OmpF porin of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:1309-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hancock, R. E., and P. G. Wong. 1984. Compounds which increase the permeability of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 26:48-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansch, C., A. Leo, and D. H. Hoekman. 1995. Exploring QSAR. II. Hydrophobic, electronic, and steric constants. American Chemical Society, Washington, D.C.

- 21.Harder, K. J., H. Nikaido, and M. Matsuhashi. 1981. Mutants of Escherichia coli that are resistant to certain beta-lactam compounds lack the OmpF porin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 20:549-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heifets, L. B. 1982. Synergistic effect of rifampin, streptomycin, ethionamide, and ethambutol on Mycobacterium intracellulare. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 125:43-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinz, C., S. Karosi, and M. Niederweis. 2003. High level expression of the mycobacterial porin MspA in Escherichia coli and purification of the recombinant protein. J. Chromatogr. B 790:337-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heinz, C., and M. Niederweis. 2000. Selective extraction and purification of a mycobacterial outer membrane protein. Anal. Biochem. 285:113-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirai, K., H. Aoyama, T. Irikura, S. Iyobe, and S. Mitsuhashi. 1986. Differences in susceptibility to quinolones of outer membrane mutants of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 29:535-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes, D. 2003. Exploiting genomics, genetics and chemistry to combat antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4:432-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Im, W., and B. Roux. 2002. Ions and counterions in a biological channel: a molecular dynamics simulation of OmpF porin from Escherichia coli in an explicit membrane with 1 M KCl aqueous salt solution. J. Mol. Biol. 319:1177-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson, M., C. Raynaud, M. A. Laneelle, C. Guilhot, C. Laurent-Winter, D. Ensergueix, B. Gicquel, and M. Daffé. 1999. Inactivation of the antigen 85C gene profoundly affects the mycolate content and alters the permeability of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell envelope. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1573-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaffe, A., Y. A. Chabbert, and O. Semonin. 1982. Role of porin proteins OmpF and OmpC in the permeation of beta-lactams. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22:942-948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jarlier, V., L. Gutmann, and H. Nikaido. 1991. Interplay of cell wall barrier and β-lactamase activity determines high resistance to β-lactam antibiotics in Mycobacterium chelonae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:1937-1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jarlier, V., and H. Nikaido. 1994. Mycobacterial cell wall: structure and role in natural resistance to antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 123:11-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jarlier, V., and H. Nikaido. 1990. Permeability barrier to hydrophilic solutes in Mycobacterium chelonei. J. Bacteriol. 172:1418-1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koronakis, V., A. Sharff, E. Koronakis, B. Luisi, and C. Hughes. 2000. Crystal structure of the bacterial membrane protein TolC central to multidrug efflux and protein export. Nature 405:914-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kremer, L. S., and G. S. Besra. 2002. Current status and future development of antitubercular chemotherapy. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 11:1033-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lambert, P. A. 2002. Cellular impermeability and uptake of biocides and antibiotics in gram-positive bacteria and mycobacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92(Suppl.):46S-54S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu, J., C. E. Barry III, G. S. Besra, and H. Nikaido. 1996. Mycolic acid structure determines the fluidity of the mycobacterial cell wall. J. Biol. Chem. 271:29545-29551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mailaender, C., N. Reiling, H. Engelhardt, S. Bossmann, S. Ehlers, and M. Niederweis. 2004. The MspA porin promotes growth and increases antibiotic susceptibility of both Mycobacterium bovis BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology 150:853-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marciano, D. K., M. Russel, and S. M. Simon. 1999. An aqueous channel for filamentous phage export. Science 284:1516-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakae, R., and T. Nakae. 1982. Diffusion of aminoglycoside antibiotics across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22:554-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niederweis, M. 2003. Mycobacterial porins—new channel proteins in unique outer membranes. Mol. Microbiol. 49:1167-1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niederweis, M., S. Ehrt, C. Heinz, U. Klocker, S. Karosi, K. M. Swiderek, L. W. Riley, and R. Benz. 1999. Cloning of the mspA gene encoding a porin from Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 33:933-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nikaido, H. 1976. Outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium. Transmembrane diffusion of some hydrophobic substances. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 433:118-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nikaido, H. 1994. Porins and specific diffusion channels in bacterial outer membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 269:3905-3908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nikaido, H. 2001. Preventing drug access to targets: cell surface permeability barriers and active efflux in bacteria. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 12:215-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nikaido, H. 1994. Prevention of drug access to bacterial targets: permeability barriers and active efflux. Science 264:382-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nikaido, H. 1985. Role of permeability barriers in resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics. Pharmacol. Ther. 27:197-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nikaido, H., and S. Normark. 1987. Sensitivity of Escherichia coli to various beta-lactams is determined by the interplay of outer membrane permeability and degradation by periplasmic beta-lactamases: a quantitative predictive treatment. Mol. Microbiol. 1:29-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nikaido, H., E. Y. Rosenberg, and J. Foulds. 1983. Porin channels in Escherichia coli: studies with beta-lactams in intact cells. J. Bacteriol. 153:232-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nikaido, H., and M. Vaara. 1985. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiol. Rev. 49:1-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paul, T. R., and T. J. Beveridge. 1992. Reevaluation of envelope profiles and cytoplasmic ultrastructure of mycobacteria processed by conventional embedding and freeze-substitution protocols. J. Bacteriol. 174:6508-6517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poole, K. 2002. Outer membranes and efflux: the path to multidrug resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 3:77-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pugsley, A. P., and C. A. Schnaitman. 1978. Outer membrane proteins of Escherichia coli. VII. Evidence that bacteriophage-directed protein 2 functions as a pore. J. Bacteriol. 133:1181-1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramaswamy, S., and J. M. Musser. 1998. Molecular genetic basis of antimicrobial agent resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: 1998 update. Tuber. Lung Dis. 79:3-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Riess, F. G., U. Dorner, B. Schiffler, and R. Benz. 2001. Study of the properties of a channel-forming protein of the cell wall of the gram-positive bacterium Mycobacterium phlei. J. Membr. Biol. 182:147-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sander, P., A. Meier, and E. C. Böttger. 1995. rpsL+: a dominant selectable marker for gene replacement in mycobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 16:991-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sawai, T., R. Hiruma, N. Kawana, M. Kaneko, F. Taniyasu, and A. Inami. 1982. Outer membrane permeation of beta-lactam antibiotics in Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, and Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22:585-592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schäfer, M., T. R. Schneider, and G. M. Sheldrick. 1996. Crystal structure of vancomycin. Structure 4:1509-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schulz, G. E. 1993. Bacterial porins: structure and function. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 5:701-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schulze-Röbbecke, R., B. Janning, and R. Fischeder. 1992. Occurrence of mycobacteria in biofilm samples. Tuber. Lung Dis. 73:141-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Srinivasan, A., J. D. Dick, and T. M. Perl. 2002. Vancomycin resistance in staphylococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:430-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stahl, C., S. Kubetzko, I. Kaps, S. Seeber, H. Engelhardt, and M. Niederweis. 2001. MspA provides the main hydrophilic pathway through the cell wall of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 40:451-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takayama, K., E. L. Armstrong, K. A. Kunugi, and J. O. Kilburn. 1979. Inhibition by ethambutol of mycolic acid transfer into the cell wall of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 16:240-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Trias, J., and R. Benz. 1994. Permeability of the cell wall of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 14:283-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Horn, K. G., C. A. Gedris, and K. M. Rodney. 1996. Selective isolation of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:924-927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Winder, F. G., and P. B. Collins. 1970. Inhibition by isoniazid of synthesis of mycolic acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 63:41-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang, Y., S. Dhandayuthapani, and V. Deretic. 1996. Molecular basis for the exquisite sensitivity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to isoniazid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:13212-13216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zimmer, B. L., D. R. DeYoung, and G. D. Roberts. 1982. In vitro synergistic activity of ethambutol, isoniazid, kanamycin, rifampin, and streptomycin against Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22:148-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]