Abstract

The MICs of GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin for 164 macrolide-susceptible and 161 macrolide-resistant pneumococci were low. The MICs of GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin for macrolide-resistant strains were similar, irrespective of the resistance genotypes of the strains. Clindamycin was active against all macrolide-resistant strains except those with erm(B) and one strain with a 23S rRNA mutation. GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin at two times their MICs were bactericidal after 24 h for 7 to 8 of 12 strains. Serial passages of 12 strains in the presence of sub-MICs yielded 54 mutants, 29 of which had changes in the L4 or L22 protein or the 23S rRNA sequence. Among the macrolide-susceptible strains, resistant mutants developed most rapidly after passage in the presence of clindamycin, GW 773546, erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin and slowest after passage in the presence of GW 708408 and telithromycin. Selection of strains for which MICs were ≥0.5 μg/ml from susceptible parents occurred only with erythromycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin, and clindamycin; 36 resistant clones from susceptible parent strains had changes in the sequences of the L4 or L22 protein or 23S rRNA. No mef(E) strains yielded resistant clones after passage in the presence of erythromycin and azithromycin. Selection with GW 773546, GW 708408, telithromycin, and clindamycin in two mef(E) strains did not raise the erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin MICs more than twofold. There were no change in the ribosomal protein (L4 or L22) or 23S rRNA sequences for 15 of 18 mutants selected for macrolide resistance; 3 mutants had changes in the L22-protein sequence. GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin selected clones for which MICs were 0.03 to >2.0 μg/ml. Single-step studies showed mutation frequencies <5.0 × 10−10 to 3.5 × 10−7 for GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin for macrolide-susceptible strains and 1.1 × 10−7 to >4.3 × 10−3 for resistant strains. The postantibiotic effects of GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin were 2.4 to 9.8 h.

The incidence of pneumococci resistant to penicillin G and other β-lactam and non-β-lactam compounds is increasing at an alarming rate worldwide, including the United States (8, 10, 11, 18). Penicillin and macrolide resistance rates of at least 50% have been observed in many countries; and the major foci of resistance at present include Spain, France, Central and Eastern Europe, and Asia (1, 12, 13, 16, 22, 30).

A recent survey in the United States has shown an increase in the rates of resistance to penicillin, from <5% before 1989 (when penicillin MICs were ≥2.0 μg/ml for <0.02% of isolates) to 6.6% in 1991-1992 (when penicillin MICs were ≥2.0 μg/ml for 1.3% of isolates) (4). In another, more recent survey testing strains isolated in 1997 (13), 50.4% of 1,476 clinically significant pneumococcal isolates were not susceptible to penicillin. Of all strains tested, approximately 33% were macrolide resistant, with the highest rate of macrolide resistance seen in penicillin-resistant strains for which penicillin MICs were ≥2.0 μg/ml. Jacobs and coworkers (14) have also described the worldwide prevalence of pneumococci isolated during 1998 and 2000 for which MICs were ≥2.0 μg/ml to be 18.2%, with an overall macrolide resistance rate of 24.6%. It is also important that the rates of isolation of penicillin-intermediate and -resistant pneumococci from the middle ear fluids from patients with refractory otitis media are higher (approximately 30%) than their rates of isolation from other isolation sites (2). The problem of drug-resistant pneumococci is compounded by the ability of resistant clones to spread from country to country and continent to continent (19, 20).

Pneumococci which are resistant to erythromycin show cross-resistance to macrolides (13, 14, 17, 29). Telithromycin, the first clinically available ketolide, is more potent against macrolide-resistant pneumococci, with the MICs of telithromycin being significantly lower than those of erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin (9, 32). Telithromycin MICs are similar irrespective of the macrolide resistance mechanism for pneumococci (15, 27).

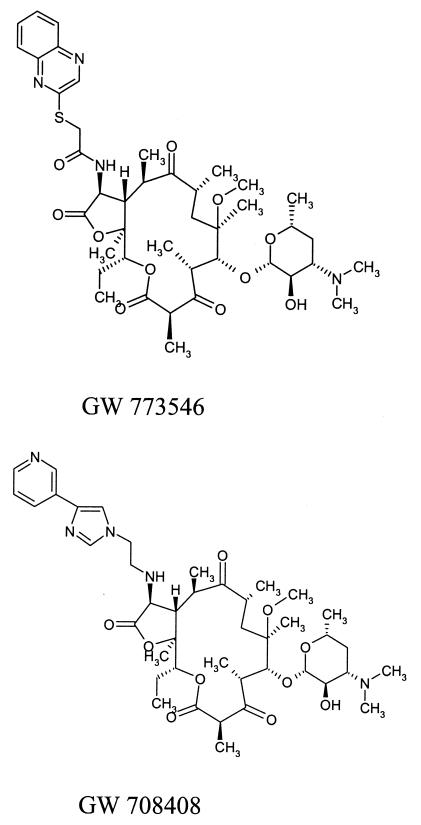

GW 773546 and GW 708408 are two new 14-membered macrolides from the clarithromycin scaffold (Fig. 1). The purpose of this study was to compare the antipneumococcal activities of these two novel macrolides, GW 773546 and GW 708408 (GlaxoSmithKline Laboratories, Collegeville, Pa., in collaboration with PLIVA Research Laboratories, Zagreb, Croatia), with those of erythromycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin, clindamycin, and telithromycin by (i) determining by the agar dilution method the MICs for 325 strains with different susceptibilities to penicillin G and macrolides including macrolide-resistant strains with defined resistance phenotypes; (ii) broth macrodilution and time-kill studies of all drugs mentioned above with 12 selected pneumococcal strains; (iii) multistep and single-step studies to test the capabilities of all compounds to select for resistant mutants of 12 Streptococcus pneumoniae strains; and (iv) postantibiotic effect (PAE) studies with all compounds and 12 strains.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of two novel macrolides, GW 773546 and GW 708408.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

Recently isolated pneumococci, comprising 121 penicillin-susceptible isolates (MICs ≤ 0.06 μg/ml), 99 penicillin-intermediate isolates (MICs = 0.125 to 1.0 μg/ml), and 105 penicillin-resistant isolates (MICs = 2.0 to 16.0 μg/ml) (24), were tested by the agar dilution method. Of these, 164 isolates were erythromycin susceptible (MICs ≤ 0.25 μg/ml) and 161 were erythromycin resistant (MICs ≥ 0.5 μg/ml) (24). Of the 161 resistant isolates, 79 isolates had erm(B), 57 isolates possessed mef(E), 2 isolates contained erm(A), and 1 isolate had both erm(B) and mef(E); 19 strains were characterized by alterations in the sequence of the L4 protein, and 3 isolates had mutations in the 23S rRNA sequence. Twelve strains were tested by time-kill studies: 3 were erythromycin susceptible, 3 contained erm(B), 3 had mef(E), 2 had an alteration in the L4 protein, and 1 had a mutation in 23S rRNA. Six erythromycin-susceptible isolates (MICs ≤ 0.06 μg/ml), three isolates with erm(B) and three isolates with mef(E), were examined by single-step and multistep selection analyses and PAE studies.

Antimicrobials and MIC testing.

GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin powders for susceptibility testing were obtained from GlaxoSmithKline Laboratories, Collegeville, Pa. Other antimicrobials were obtained from their respective manufacturers. The agar dilution method was performed with Mueller-Hinton agar (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) supplemented with 5% sheep blood (26, 27). Standard quality control strains, including S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 (24), were included in each run of the agar dilution method. For all 325 strains, inocula of 104 CFU/spot were used, as described previously (6, 25, 27). The MICs for the 12 strains tested by the time-kill method were detected by inspection of broth macrodilutions (6, 25).

Time-kill testing.

For the time-kill studies, glass tubes containing 5 ml of cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (BBL Microbiology Systems) and 5% lysed horse blood with doubling antibiotic concentrations were inoculated with 5 × 105 to 5 × 106 CFU/ml and incubated at 35°C in a shaking water bath. Antibiotic concentrations were chosen to comprise 3 doubling dilutions above and 2 dilutions below the agar dilution MIC. Growth controls with inoculum but no antibiotic were included in each experiment (6, 25).

Lysed horse blood was prepared as described previously (6, 25). The bacterial inoculum was prepared by suspending growth from an overnight blood agar plate in Mueller-Hinton broth until the turbidity matched that of a no. 1 McFarland standard. Dilutions required to obtain the correct inoculum (5 × 105 to 5 × 106 CFU/ml) were determined by prior viability studies with each strain (6, 25).

To inoculate each tube with a serial dilution of antibiotic, 50 μl of diluted inoculum was delivered beneath the surface of the broth with a pipette. The tubes were then vortexed and plated for viability counts within 10 min (approximately 0.2 h). The original inoculum was determined by using the untreated growth control. Only tubes containing an initial inoculum within the range of 5 × 105 to 5 × 106 CFU/ml were acceptable (6, 25).

Viability counts for the antibiotic-containing suspensions were performed by plating 10-fold dilutions of 0.1-ml aliquots from each tube in sterile Mueller-Hinton broth onto Trypticase soy agar-5% sheep blood agar plates (BBL Microbiology Systems). The recovery plates were incubated for up to 72 h. Colony counts were performed for plates that yielded from 30 to 300 colonies. The lower limit of sensitivity of the colony counting method was 300 CFU/ml (25). Drug carryover was minimized by dilution, as described previously (25).

Time-kill assays were analyzed by determining the number of strains which yielded changes in the log10 number of CFU per milliliter of −1, −2, and −3 at 3, 6, 12, and 24 h compared to the counts at time zero. The lowest concentration of the antimicrobials that reduced the original inoculum by ≥3 log10 CFU/ml (99.9%) at each of the time periods was considered bactericidal, and the lowest concentration that reduced the original inoculum by 0 to <3 log10 CFU/ml was considered bacteriostatic. With the sensitivity threshold and inocula used in these studies, no problems were encountered in delineating 99.9% killing, when it was present. The problem of drug carryover was addressed by dilution, as described previously (6, 23). For time-kill testing of the macrolides, only strains for which macrolide MICs were ≤8.0 μg/ml were tested because of problems with solubilization at high concentrations and a lack of clinical significance. Thus, only the ketolides and the two new macrolides were tested against erm(B) strains; and only GW 773546, GW 708408, telithromycin, and clindamycin were tested against mef(E) strains and strains with mutations in the L4-protein and 23S rRNA sequences.

Mechanism of macrolide resistance.

All macrolide-resistant clinical strains and selected resistant clones (see below) were tested for the presence of the erm(B), erm(A), and mef(E) genes by PCR amplification (31). The presence of mutations in the L4 and L22 proteins and 23S rRNA were examined by using the primers and conditions described previously (22). After PCR amplification, the products were purified with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). The nucleotide sequences were obtained by direct sequencing with a CEQ8000 genetic analysis system (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, Calif.).

Multistep mutation analysis.

Six susceptible strains (see strains 1 to 6 in Table 4) and six macrolide-resistant strains (strains 7 to 9 [erm(B)-positive strains] and strains 10 to 12 [mef(E)-positive strains]; see Table 4) were selected for the multistep selection study. Glass tubes containing 1 ml of cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (BBL Microbiology Systems) supplemented with 5% lysed horse blood with doubling antibiotic dilutions were inoculated with approximately 5 × 105 CFU/ml. The antibiotic concentrations ranged from 4 doubling dilutions above to 3 doubling dilutions below the MIC of each agent for each strain. The initial inoculum was prepared by suspending the growth from an overnight Trypticase soy blood agar plate (BBL Microbiology Systems) in Mueller-Hinton broth. The tubes were incubated at 35°C for 24 h. Daily passages were then performed for a maximum of 50 days by taking a 10-μl inoculum from the tube with the concentration nearest the MIC (usually 1 to 2 dilutions below) which had the same turbidity as that of the antibiotic-free control tubes. When an MIC for a strain increased more than fourfold, passaging was stopped and the strains were subcultured in antibiotic-free medium for 10 serial passages. A minimum of 14 passages were made prior to termination (23, 26). The identities of all resistant strains and parent isolates were tested by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) before and after resistance selection. PFGE of SmaI-digested DNA was performed with a CHEF DR III apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) with the following run parameters: a switch time of 5 to 20 s and a run time of 16 h (22). All resistant clones selected were examined for changes in their mechanisms of resistance, as described above.

TABLE 4.

Results of multistep resistance selection by erythromycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin, telithromycin, clindamycin, GW 708408, and GW 773546a

| Straina | Selecting agent | Initial MIC (μg/ml) | Selected resistance

|

MIC (μg/ml) after 10 antibiotic-free subcultures

|

Change in sequence

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of passages | MIC (μg/ml) | ERY | AZI | CLARI | TELI | CLINDA | GW 708 | GW 773 | L4 protein | L22 protein | 23S rRNA | |||

| 1 | ERY | 0.06 | 38 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.008 | 0.03 | 0.004 | 0.004 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg |

| AZI | 0.06 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.008 | 0.06 | 0.008 | 0.004 | K68R, A73T | n. chg | n. chg | |

| TELI | 0.004 | 20 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | n. chg | ins 80SEAFAN | n. chg | |

| CLINDA | 0.016 | 18 | 0.25 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 0.016 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.016 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| GW 708 | 0.004 | 30 | 0.06 | 2.0 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | n. chg | R92H, G95D | n. chg | |

| GW 773 | 0.004 | 26 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | n. chg | G95D | n. chg | |

| 2 | ERY | 0.06 | 24 | 64.0 | 64.0 | 64.0 | 32.0 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.03 | E13K | n. chg | A2059C |

| AZI | 0.125 | 42 | 1.0 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.016 | 0.06 | 0.008 | 0.008 | G71C | n. chg | n. chg | |

| CLARI | 0.016 | 32 | 0.125 | 1.0 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| CLINDA | 0.03 | 18 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2.0 | 0.06 | 0.008 | 0.5 | 0.016 | 0.008 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| GW 708 | 0.008 | 50 | 0.06 | 2.0 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.016 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| GW 773 | 0.004 | 40 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.016 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| 3 | ERY | 0.06 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.016 | 0.03 | 0.016 | 0.008 | Q67K, G69E | n. chg | n. chg |

| AZI | 0.125 | 22 | 1.0 | 0.25 | 1.0 | 0.06 | 0.016 | 1.0 | 0.016 | 0.008 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| CLARI | 0.016 | 14 | 32.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 32.0 | 0.25 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.25 | n. chg | n. chg | A2058T | |

| TELI | 0.008 | 20 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.016 | 0.125 | 0.06 | n. chg | A93T | n. chg | |

| CLINDA | 0.03 | 18 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 1.0 | 0.06 | 0.008 | 0.5 | 0.016 | 0.004 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| GW 708 | 0.008 | 26 | 0.125 | 2.0 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.016 | 0.125 | 0.125 | n. chg | A93E | n. chg | |

| GW 773 | 0.004 | 16 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | n. chg | A93E | n. chg | |

| 4 | ERY | 0.06 | 24 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.008 | 0.125 | 0.008 | 0.004 | A10T | n. chg | G2057A |

| AZI | 0.125 | 26 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 0.125 | 8.0 | 0.25 | 0.125 | E13K | n. chg | A2058G | |

| TELI | 0.008 | 40 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | A10T | A93T | n. chg | |

| CLINDA | 0.03 | 22 | 16.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 0.125 | 16.0 | 0.25 | 0.125 | A10T | n. chg | A2058G | |

| GW 708 | 0.008 | 34 | 0.06 | >64.0 | 8.0 | 64.0 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.06 | A10T | n. chg | n. chg | |

| GW 773 | 0.004 | 26 | >0.06 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 0.125 | 8.0 | 0.25 | 0.125 | A10T | n. chg | A2058G | |

| 5 | ERY | 0.06 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.008 | 0.25 | 0.004 | 0.004 | n. chg | n. chg | G2057T |

| AZI | 0.125 | 42 | >64.0 | 8.0 | >64.0 | 4.0 | 0.016 | 1.0 | 0.016 | 0.008 | n. chg | n. chg | A2058G | |

| CLARI | 0.016 | 22 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 0.125 | 4.0 | 0.25 | 0.125 | n. chg | n. chg | A2058G | |

| TELI | 0.008 | 32 | 0.06 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.125 | n. chg | A93E | n. chg | |

| CLINDA | 0.03 | 18 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.03 | 0.004 | 0.25 | 0.004 | 0.002 | E13K | n. chg | n. chg | |

| GW 773 | 0.004 | 16 | 0.06 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.125 | 0.06 | n. chg | A93E | n. chg | |

| 6 | ERY | 0.06 | 26 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.125 | 0.016 | 0.06 | 0.016 | 0.008 | ins 66QS | n. chg | n. chg |

| AZI | 0.125 | 14 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.125 | 0.016 | 0.06 | 0.016 | 0.008 | ins 66QS | n. chg | n. chg | |

| CLARI | 0.016 | 14 | 64.0 | >64.0 | 8.0 | 64.0 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.125 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| CLINDA | 0.03 | 26 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.03 | 0.008 | 0.25 | 0.008 | 0.004 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| GW 773 | 0.004 | 40 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | n. chg | G95D | n. chg | |

| 7 | TELI | 0.03 | 14 | >2.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 0.06 | >64.0 | 0.06 | 0.06 | n. chg | S96P | n. chg |

| GW 708 | 0.03 | 14 | >2.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 16.0 | >64.0 | 64.0 | 16.0 | n. chg | R31K | n. chg | |

| GW 773 | 0.016 | 14 | >1.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 0.5 | >64.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| 8 | TELI | 0.125 | 14 | >2.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 1.0 | >64.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg |

| GW 708 | 0.03 | 14 | >2.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 16.0 | >64.0 | 64.0 | 16.0 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| GW 773 | 0.06 | 14 | >1.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 8.0 | >64.0 | 32.0 | 8.0 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| 9 | TELI | 0.06 | 14 | >2.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 0.25 | >64.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg |

| GW 708 | 0.016 | 14 | >2.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 1.0 | >64.0 | 2.0 | 0.5 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| GW 773 | 0.016 | 14 | >1.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 0.5 | >64.0 | 0.25 | 0.5 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| 11 | CLARI | 4.0 | 28 | 32.0 | 32.0 | 32.0 | 16.0 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.125 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg |

| TELI | 0.125 | 14 | 2.0 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 8.0 | 2.0 | 0.03 | 2.0 | 0.5 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| CLINDA | 0.016 | 18 | 0.25 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 2.0 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.06 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| GW 708 | 0.125 | 14 | 2.0 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 8.0 | 2.0 | 0.03 | 2.0 | 0.5 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| GW 773 | 0.03 | 14 | 0.5 | 8.0 | 16.0 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 0.03 | 2.0 | 0.25 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| 12 | TELI | 0.125 | 14 | 1.0 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 0.06 | 1.0 | 0.25 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg |

| CLINDA | 0.03 | 37 | 0.25 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 4.0 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.03 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| GW 708 | 0.25 | 14 | 2.0 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 0.06 | 2.0 | 0.25 | n. chg | n. chg | n. chg | |

| GW 773 | 0.03 | 14 | 0.25 | 8.0 | 16.0 | 8.0 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 1.0 | 0.125 | n. chg | S96P, E113K | n. chg | |

Strains 1 to 6 are susceptible, strains 7 to 12 are macrolide resistant, 7 to 9 are erm(B) positive, and strains 10 to 12 are mef(E) positive. Strain 10 did not yielded any mutants, so data for this strain are not presented here. Abbreviations: ERY, erythromycin; AZI, azithromycin; CLARI, clarithromycin; TELI, telithromycin; CLINDA, clindamycin; GW 708, GW 708408; GW 773, GW 773546; n. chg, no change in the sequence detected; ins, insertion.

Single-step mutation analysis.

The frequency of spontaneous single-step mutations was determined by spreading suspensions (approximately 1010 CFU/ml) on brain heart infusion agar (BBL Microbiology Systems) with 5% sheep blood at the MIC and at two, four, and eight times the MIC, as described previously (23). After incubation at 35°C in 5% CO2 for 48 to 72 h, the frequency of resistance was calculated as the number of resistant colonies per inoculum. Identity between resistant clones and parents was done by PFGE, as described above. The mechanisms of resistance of eight selected macrolide-resistant clones were determined as described previously (22, 31). Single-step studies were not performed with erythromycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin, and clindamycin for the three strains with erm(B).

PAEs.

The PAEs were determined by the viable plate count method (7) with Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with 5% lysed horse blood for the testing of the pneumococci. The PAE was induced by exposure to 10 times the MIC of each compound for 1 h. For PAE testing, tubes containing 5 ml of broth with antibiotic were inoculated with approximately 5 × 106 CFU/ml. Inocula were prepared by suspending the growth from an overnight blood agar plate in broth. Growth controls with inoculum but no antibiotic were included in each experiment. The inoculated test tubes were placed in a shaking water bath at 35°C for an exposure period of 1 h. At the end of the exposure period, cultures were diluted 1:1,000 in prewarmed broth to remove the antibiotic by dilution. Antibiotic removal was confirmed by comparing the growth curve of a control culture containing no antibiotic to the growth curve of another culture containing the antibiotic at 0.01 the exposure concentration. Viability counts were determined before exposure and immediately after dilution (0 h) and then every 2 h until the turbidity of the tube reached that of a no. 1 McFarland standard. The PAE was defined as T − C, where T is the time required for the viability counts of an antibiotic-exposed culture to increase 1 log10 above the counts immediately after dilution and C is the corresponding time for the growth control (7).

RESULTS

The MICs for the strains classified by their erythromycin susceptibilities as well as by their erythromycin resistance mechanisms are presented in Table 1. The MICs of GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin were similarly low for both macrolide-susceptible pneumococci (MICs ≤ 0.004 to 0.03 μg/ml) and macrolide-resistant pneumococci (MICs ≤ 0.004 to 2.0 μg/ml). The GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin MICs for macrolide-resistant strains were similar irrespective of the macrolide resistance mechanisms of the strains. Clindamycin was active against strains with mef(E) and erm(A), all strains with mutations in the sequence of the L4 protein, and all but one of the strains with mutations in the 23S rRNA sequence. Uniform cross-resistance between erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin was seen.

TABLE 1.

Agar dilution MICs for 325 strains classified by susceptibility to erythromycin

| Antibiotic and strain | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | |

| Penicillin | |||

| Erythromycin susceptible (164)b | ≤0.008-4.0 | 0.125 | 2.0 |

| Erythromycin resistant (161) | 0.016->8.0 | 0.5 | 8.0 |

| erm(B) (79) | 0.016->8.0 | 1.0 | 8.0 |

| erm(A) (2) | 0.03 | ||

| mef(E) (57) | 0.016-8.0 | 0.06 | 4.0 |

| erm(B) + mef(E) (1) | 0.016 | ||

| Mutations in L4 protein (19) | 2.0->8.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 |

| Mutation in 23S rRNA (3) | 0.03-0.5 | ||

| GW 773546 | |||

| Erythromycin susceptible | ≤0.004-0.016 | 0.008 | 0.016 |

| Erythromycin resistant | ≤0.004-2.0 | 0.03 | 0.25 |

| erm(B) | ≤0.004-1.0 | 0.03 | 0.5 |

| erm(A) | 0.016 | ||

| mef(E) | ≤0.004-0.25 | 0.06 | 0.125 |

| erm(B) + mef(E) | 2.0 | ||

| Mutations in L4 protein | 0.03-0.25 | 0.06 | 0.125 |

| Mutation in 23S rRNA | 0.016-0.03 | ||

| GW 708408 | |||

| Erythromycin susceptible | ≤0.004-0.016 | 0.008 | 0.016 |

| Erythromycin resistant | ≤0.004-2.0 | 0.125 | 0.5 |

| erm(B) | ≤0.004-2.0 | 0.03 | 1.0 |

| erm(A) | 0.016 | ||

| mef(E) | 0.03-1.0 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| erm(B) + mef(E) | 2.0 | ||

| Mutations in L4 protein | 0.125-0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Mutation in 23S rRNA | ≤0.004-0.06 | ||

| Telithromycin | |||

| Erythromycin susceptible | ≤0.004-0.03 | 0.016 | 0.016 |

| Erythromycin resistant | ≤0.004-1.0 | 0.06 | 0.5 |

| erm(B) | ≤0.004-1.0 | 0.03 | 0.5 |

| erm(A) | 0.016 | ||

| mef(E) | 0.03-0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| erm(B) + mef(E) | 1.0 | ||

| Mutations in L4 protein | 0.03-0.25 | 0.06 | 0.125 |

| Mutation in 23S rRNA | 0.008-0.03 | ||

| Erythromycin | |||

| Erythromycin susceptible | ≤0.016-0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Erythromycin resistant | 1.0->64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 |

| erm(B) | 1.0->64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 |

| erm(A) | 1.0-2.0 | ||

| mef(E) | 1.0-64.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 |

| erm(B) + mef(E) | >64.0 | ||

| Mutations in L4 protein | 64.0->64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 |

| Mutation in 23S rRNA | 16.0-32.0 | ||

| Azithromycin | |||

| Erythromycin susceptible | ≤0.016-0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| Erythromycin resistant | 1.0->64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 |

| erm(B) | 4.0->64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 |

| erm(A) | 2.0-4.0 | ||

| mef(E) | 1.0->64.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 |

| erm(B) + mef(E) | >64.0 | ||

| Mutations in L4 protein | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 |

| Mutation in 23S rRNA | >64.0 | ||

| Clarithromycin | |||

| Erythromycin susceptible | ≤0.016-0.125 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Erythromycin resistant | 0.5->64.0 | 16.0 | >64.0 |

| erm(B) | 1.0->64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 |

| erm(A) | 0.5 | ||

| mef(E) | 0.5-16.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 |

| erm(B) + mef(E) | >64.0 | ||

| Mutations in L4 protein | 16.0-64.0 | 16.0 | 32.0 |

| Mutation in 23S rRNA | 4.0-16.0 | ||

| Clindamycin | |||

| Erythromycin susceptible | ≤0.016-0.125 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Erythromycin resistant | ≤0.016->64.0 | 0.25 | >64.0 |

| erm(B) | 0.06->64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 |

| erm(A) | 0.125 | ||

| mef(E) | ≤0.016-0.125 | 0.06 | 0.125 |

| erm(B) + mef(E) | >64.0 | ||

| Mutations in L4 protein | 0.06-0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| Mutation in 23S rRNA | 0.25-1.0 | ||

50% and 90%, MICs at which 50 and 90% of isolates, respectively, are inhibited. Values in parentheses are numbers of isolates.

The MICs for the 12 strains tested by the time-kill method are listed in Table 2, and the results of the time-kill studies are presented in Table 3. GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin were bactericidal for seven to eight strains at two times the MIC after 24 h. GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin were observed to have bacteriostatic activities against the three strains with the erm(B) gene. The killing kinetics of GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin were consistent with their MICs, which were very similar. Clindamycin, erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin at two times their MICs were bactericidal against four to seven strains tested after 24 h.

TABLE 2.

MICs for pneumococcal strains tested by time-kill experiments

| Drug | MIC (μg/ml)

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 2b | 3b | 4c | 5c | 6c | 7d | 8d | 9d | 10e | 11e | 12e | |

| Penicillin G | 0.5 | 8.0 | 4.0 | 0.03 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 0.03 | 0.016 | 0.5 | 0.016 |

| GW 773546 | 0.03 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 0.016 | 0.03 | 0.016 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| GW 708408 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.016 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.008 |

| Telithromycin | 0.03 | 0.125 | 0.03 | 0.016 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.008 |

| Erythromycin | 32.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.06 |

| Azithromycin | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 0.016 | 0.06 | 0.125 |

| Clarithromycin | 16.0 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 32.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.03 |

| Clindamycin | 1.0 | 0.06 | 0.06 | >64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 0.03 | 0.016 | 0.03 | 0.016 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

23S rRNA protein mutation.

L4 protein mutation.

erm(B).

mef(E).

Erythromycin susceptible.

TABLE 3.

Time-kill study resultsa

| Drug and MIC | No. of strains for which the levels of killingb were as indicated at the following times:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 h

|

6 h

|

12 h

|

24 h

|

|||||||||

| −1 | −2 | −3 | −1 | −2 | −3 | −1 | −2 | −3 | −1 | −2 | −3 | |

| GW 773546 | ||||||||||||

| 4× MIC | 10 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 6 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 6 | 11 | 11 | 8 |

| 2× MIC | 6 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 11 | 8 | 5 | 11 | 11 | 8 |

| MIC | 5 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 11 | 9 | 5 |

| GW 708408 | ||||||||||||

| 4× MIC | 10 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 5 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 5 | 11 | 11 | 9 |

| 2× MIC | 7 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 11 | 9 | 5 | 11 | 11 | 7 |

| MIC | 5 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 4 |

| Telithromycin | ||||||||||||

| 4× MIC | 9 | 4 | 1 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 12 | 11 | 7 | 12 | 12 | 10 |

| 2× MIC | 8 | 4 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 12 | 11 | 7 | 12 | 12 | 8 |

| MIC | 6 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 12 | 8 | 3 | 11 | 8 | 4 |

| Erythromycin | ||||||||||||

| 4× MIC | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 4 |

| 2× MIC | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 4 |

| MIC | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| Azithromycin | ||||||||||||

| 4× MIC | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| 2× MIC | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| MIC | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| Clarithromycin | ||||||||||||

| 4× MIC | 3 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 2× MIC | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| MIC | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 3 |

| Clindamycin | ||||||||||||

| 4× MIC | 7 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 8 |

| 2× MIC | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 7 |

| MIC | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 6 | 2 |

Only GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin were tested with the three strains with erm(B).

−1, 90% killing; −2, 99% killing; −3, 99.9% killing.

Multistep resistance selection analysis.

The initial MICs for the parent strains and resistant mutants resulting from serial daily subculture in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of antimicrobials are summarized in Table 4. Fifty-four mutants were detected, and 29 had changes in the L4 or L22 ribosomal protein sequence or in the 23S RNA sequence (Table 4). Serial broth passages in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of each drug for macrolide-susceptible strains showed that the development of resistant mutants (a more than fourfold increase in the original MIC) occurred the most rapidly for clindamycin, GW 773546, erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin and occurred the most slowly for GW 708408 and telithromycin. GW 708408, telithromycin, and clarithromycin did not select for mutants of susceptible parent strains 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 (strains 2 and 6 with telithromycin, strains 5 and 6 with GW 708408, and strains 1 and 4 with clarithromycin). Selection of strains for which MICs were ≥0.5 μg/ml from parents which were originally macrolide susceptible occurred only with erythromycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin, and clindamycin. We observed 36 mutants among these strains; 10 of these had no alterations in the L4 or L22 protein or in 23S rRNA. The remaining 26 macrolide-resistant mutants had changes in the L4 protein (7 isolates), 23S rRNA (4 isolates), L4 protein and 23S rRNA (5 isolates), L4 and L22 proteins (1 isolate), and L22 protein (9 isolates) (Table 4). Selection of the strains with GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin caused maximal MICs of 0.125 μg/ml. All three parent strains with erm(B) gave rise to clones for which GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin MICs were increased after 14 days subculture (Table 4). Strains with mef(E) did not yield resistant clones with erythromycin and azithromycin after 50 subcultures; the erythromycin and azithromycin MICs for these strains two- to fourfold higher than those for their parents. Selection with GW 773546, GW 708408, telithromycin, and clindamycin in two strains with mef(E) did not raise the erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin MICs by more than twofold (Table 4). There were no changes in the sequences of ribosomal proteins (the L4 and L22 proteins) or 23S rRNA for 15 of the 18 mutants selected. Three mutants had changes in the L22-protein sequence: R31K, S96P, and E113K. Overall, GW 773546, GW 708408, telithromycin, and clindamycin selected clones for which MICs were between 0.03 and >2.0 μg/ml.

Single-step resistance selection studies.

Among the macrolide-susceptible strains, the frequencies of appearance of spontaneous resistant mutants at the MICs were 2.5 × 10−9 to 3.5 × 10−7 for GW 773546, <5.0 × 10−10 to 1.0 × 10−7 for GW 708408, and 1.5 × 10−8 to 2.0 × 10−7 for telithromycin, whereas they were < 2.5 × 10−10 to 2.0 × 10−8 for clindamycin and 4.4 × 10−9 to 1.2 × 10−3 for erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin. By contrast, for strains with mef(E), the frequencies of appearance of spontaneous resistant mutants at the MICs rose to 1.2 × 10−4 to >4.3 × 10−3 for GW 773546, 3.0 × 10−5 to 2.1 × 10−3 for GW 708408, and 2.5 × 10−6 to 1.8 × 10−4 for telithromycin, whereas they were 1.5 × 10−4 to 3.0 × 10−3 for clindamycin and 5.0 × 10−6 to 2.0 × 10−2 for erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin. For strains with erm(B), the frequencies of appearance of spontaneous resistant mutants at the MIC rose to >1.5 × 10−3 to >1.9 × 10−3 for GW 773546, 2.0 × 10−6 to >1.9 × 10−3 for GW 708408, and 1.1 × 10−7 to >1.0 × 10−3 for telithromycin (Table 5). Among the clones selected by the single-step method (Table 5), eight mutants were chosen for determination of their resistance mechanisms. Only three mutants selected for by exposure to telithromycin and GW 773546 had an alteration in the L22 protein sequence (A97D). The other five clones had no detectable changes in the sequence of the L4 or L22 protein or 23S rRNA.

TABLE 5.

Frequencies of mutations in 12 strains by single-step selection

| Straina | Selecting drugb | Frequency of mutation at:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC | 2× MIC | 4× MIC | 8× MIC | ||

| 1 | ERY | 1.1 × 10−4 | 4.0 × 10−8 | <1.0 × 10−9 | <1.0 × 10−9 |

| AZI | 3.3 × 10−4 | <1.7 × 10−10 | <1.7 × 10−10 | <1.7 × 10−10 | |

| CLARI | 2.5 × 10−7 | 5.0 × 10−8 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| TELI | 2.5 × 10−8 | 5.0 × 10−10 | 5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| CLINDAb | 2.0 × 10−8 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| GW 708 | 1.3 × 10−8 | <1.3 × 10−9 | <1.3 × 10−9 | <1.3 × 10−9 | |

| GW 773 | 1.0 × 10−7 | 6.7 × 10−10 | <3.3 × 10−10 | <3.3 × 10−10 | |

| 2 | ERY | 1.2 × 10−3 | <2.0 × 10−8 | <2.0 × 10−8 | <2.0 × 10−8 |

| AZI | 6.7 × 10−9 | <1.1 × 10−9 | <1.1 × 10−9 | <1.1 × 10−9 | |

| CLARI | 2.5 × 10−4 | 1.5 × 10−9 | 1.5 × 10−9 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| TELI | 2.0 × 10−7 | 4.0 × 10−9 | <1.0 × 10−9 | <1.0 × 10−9 | |

| CLINDA | <7.1 × 10−10 | <7.1 × 10−10 | <7.1 × 10−10 | <7.1 × 10−10 | |

| GW 708 | 1.0 × 10−7 | <2.0 × 10−9 | <2.0 × 10−9 | <2.0 × 10−9 | |

| GW 773 | 1.5 × 10−7 | <2.5 × 10−9 | <2.5 × 10−9 | <2.5 × 10−9 | |

| 3 | ERY | 9.2 × 10−6 | 5.7 × 10−9 | 1.4 × 10−9 | <1.4 × 10−9 |

| AZI | 2.0 × 10−8 | <1.0 × 10−9 | <1.0 × 10−9 | <1.0 × 10−9 | |

| CLARI | 1.5 × 10−6 | 2.5 × 10−8 | 1.0 × 10−9 | 1.5 × 10−9 | |

| TELI | 1.7 × 10−8 | 3.3 × 10−9 | 1.3 × 10−9 | <6.7 × 10−10 | |

| CLINDA | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| GW 708 | 5.0 × 10−9 | <1.0 × 10−9 | <1.0 × 10−9 | <1.0 × 10−9 | |

| GW 773 | 7.5 × 10−8 | 7.5 × 10−9 | <2.5 × 10−10 | <2.5 × 10−10 | |

| 4 | ERY | 2.5 × 10−7 | <5.0 × 10−9 | <5.0 × 10−9 | <5.0 × 10−9 |

| AZI | 2.3 × 10−6 | <3.3 × 10−9 | <3.3 × 10−9 | <3.3 × 10−9 | |

| CLARI | 3.3 × 10−6 | 2.5 × 10−9 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| TELI | 5.0 × 10−8 | 5.0 × 10−9 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| CLINDA | 1.7 × 10−9 | <3.3 × 10−10 | <3.3 × 10−10 | <3.3 × 10−10 | |

| GW 708 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| GW 773 | 2.5 × 10−9 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| 5 | ERYc | 6.5 × 10−8 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 |

| AZI | 5.0 × 10−8 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| CLARIc | 3.0 × 10−4 | 5.0 × 10−9 | <5.0 × 10−9 | <5.0 × 10−9 | |

| TELIc | 1.0 × 10−7 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| CLINDA | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| GW 708c | 2.5 × 10−9 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| GW 773c | 3.5 × 10−7 | 3.5 × 10−8 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| 6 | ERY | 2.0 × 10−6 | <1.0 × 10−9 | <1.0 × 10−9 | <1.0 × 10−9 |

| AZI | 4.4 × 10−9 | <1.1 × 10−9 | <1.1 × 10−9 | <1.1 × 10−9 | |

| CLARI | 7.5 × 10−5 | 5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| TELI | 1.5 × 10−8 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| CLINDA | <2.5 × 10−10 | <2.5 × 10−10 | <2.5 × 10−10 | <2.5 × 10−10 | |

| GW 708 | 3.8 × 10−8 | <1.2 × 10−9 | <1.2 × 10−9 | <1.2 × 10−9 | |

| GW 773 | 1.0 × 10−7 | <3.3 × 10−10 | <3.3 × 10−10 | <3.3 × 10−10 | |

| 7 | ERY | 8.0 × 10−4 | 4.0 × 10−5 | 3.0 × 10−6 | 2.0 × 10−6 |

| AZI | 5.0 × 10−6 | 5.0 × 10−7 | 8.3 × 10−9 | <1.7 × 10−9 | |

| CLARI | 5.0 × 10−5 | 1.8 × 10−7 | 1.3 × 10−8 | 1.7 × 10−10 | |

| TELI | 2.5 × 10−6 | 3.8 × 10−9 | <2.5 × 10−10 | <2.5 × 10−10 | |

| CLINDA | 2.0 × 10−4 | 1.4 × 10−8 | <2.0 × 10−10 | <2.0 × 10−10 | |

| GW 708 | 3.0 × 10−5 | 2.0 × 10−7 | 2.0 × 10−8 | <1.0 × 10−9 | |

| GW 773 | 1.2 × 10−4 | 1.2 × 10−7 | 2.0 × 10−9 | <2.0 × 10−10 | |

| 8 | ERY | 1.0 × 10−3 | 1.4 × 10−5 | 2.0 × 10−7 | 2.0 × 10−8 |

| AZI | 2.0 × 10−4 | 1.0 × 10−6 | 1.0 × 10−7 | <5.0 × 10−9 | |

| CLARI | 2.7 × 10−4 | 5.4 × 10−7 | <9.1 × 10−10 | <9.1 × 10−10 | |

| TELI | 1.8 × 10−4 | 4.5 × 10−8 | <9.1 × 10−10 | <9.1 × 10−10 | |

| CLINDA | 1.5 × 10−4 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| GW 708 | 1.0 × 10−3 | 1.5 × 10−6 | 1.0 × 10−8 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| GW 773 | >1.0 × 10−3 | 2.0 × 10−5 | 6.7 × 10−9 | 6.7 × 10−10 | |

| 9 | ERY | 2.0 × 10−2 | 4.0 × 10−3 | 2.0 × 10−4 | 2.0 × 10−5 |

| AZI | 1.2 × 10−3 | 2.0 × 10−5 | <1.0 × 10−8 | <1.0 × 10−8 | |

| CLARI | 2.0 × 10−3 | 6.0 × 10−4 | <1.0 × 10−9 | <1.0 × 10−9 | |

| TELI | 1.0 × 10−5 | 3.5 × 10−9 | <5.0 × 10−10 | <5.0 × 10−10 | |

| CLINDA | 3.0 × 10−3 | 1.5 × 10−3 | 1.0 × 10−7 | <1.0 × 10−9 | |

| GW 708 | 2.1 × 10−3 | 8.6 × 10−7 | 2.1 × 10−8 | <1.4 × 10−9 | |

| GW 773 | >4.3 × 10−3 | 4.3 × 10−6 | 5.7 × 10−9 | <1.4 × 10−9 | |

| 10 | ERY | NTd | NT | NT | NT |

| AZI | NT | NT | NT | NT | |

| CLARI | NT | NT | NT | NT | |

| TELI | >1.0 × 10−3 | >1.0 × 10−3 | >1.0 × 10−3 | >1.0 × 10−3 | |

| CLINDA | NT | NT | NT | NT | |

| GW 708 | >1.9 × 10−3 | >1.9 × 10−3 | >1.9 × 10−3 | >1.9 × 10−3 | |

| GW 773 | >1.9 × 10−3 | >1.9 × 10−3 | >1.9 × 10−3 | >1.9 × 10−3 | |

| 11 | ERY | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| AZI | NT | NT | NT | NT | |

| CLARI | NT | NT | NT | NT | |

| TELI | >4.3 × 10−4 | >4.3 × 10−4 | 4.3 × 10−8 | 5.7 × 10−9 | |

| CLINDA | NT | NT | NT | NT | |

| GW 708 | 4.0 × 10−5 | 1.0 × 10−6 | 1.0 × 10−6 | 2.5 × 10−7 | |

| GW 773 | >1.5 × 10−3 | >1.5 × 10−3 | >1.5 × 10−3 | >1.5 × 10−7 | |

| 12 | ERY | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| AZI | NT | NT | NT | NT | |

| CLARI | NT | NT | NT | NT | |

| TELI | 1.1 × 10−7 | 8.0 × 10−8 | <6.7 × 10−10 | <6.7 × 10−10 | |

| CLINDA | NT | NT | NT | NT | |

| GW 708 | 2.0 × 10−6 | 1.0 × 10−6 | 1.0 × 10−6 | 8.0 × 10−7 | |

| GW 773 | >1.5 × 10−3 | 7.5 × 10−4 | 3.0 × 10−4 | 1.0 × 10−4 | |

Strains 7 to 9 are mef(E) positive, and strains 10 to 12 are erm(B) positive.

See footnote a of Table 4 for the definition of the drug abbreviations.

Mutants selected from strains 5 and 1 in single steps were analyzed for alterations in the sequences of 23S rRNA and the L4 and L22 proteins.

NT, not tested.

PAE studies.

The results of the PAE studies for GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin with nine strains are presented in Table 6. GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin produced PAEs between 2.4 and 9.8 h. The PAEs for erythromycin-resistant strains with erm(B) were lower than those for the erythromycin-sensitive and resistant strains with mef(E). The mean clindamycin PAEs for three erythromycin-sensitive and three erythromycin-resistant mef(E) strains were 3.1 h (range, 2.9 to 3.4 h) and 3.1 h (range, 2.0 to 4.3 h), respectively. The PAEs of erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin for three erythromycin-sensitive strains were 2.7 h (range, 2.4 to 3.2 h), 2.3 h (range, 1.6 to 3.2 h), and 3.4 h (range, 3.1 to 3.8 h), respectively.

TABLE 6.

PAEs of GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin against nine S. pneumoniae strains

| Drug | Erythromycin-sensitive strainsa

|

Erythromycin-resistant strains [erm(B)]a

|

Erythromycin-resistant strains [mef(E)]a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC range (μg/ml) | PAEb | MIC range (μg/ml) | PAE | MIC range (μg/ml) | PAE | |

| GW 773546 | 0.0005-0.004 | 6.4 (4.0-8.6) | 0.004-0.06 | 4.5 (3.6-5.8) | 0.016-0.06 | 6.1 (4.8-7.0) |

| GW 708408 | 0.001-0.008 | 5.6 (3.1-7.3) | 0.008-0.12 | 3.5 (2.8-4.2) | 0.06-0.12 | 5.8 (5.3-6.2) |

| Telithromycin | 0.004-0.016 | 6.5 (3.6-9.2) | 0.03-0.06 | 4.1 (2.4-5.9) | 0.06-0.12 | 8.4 (6.4-9.8) |

Three strains were analyzed.

The values are the mean (range) PAE (in hours). The PAE was induced by 1 h of exposure to 10 times the MIC.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that the activities of GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin are similar to those previously described for telithromycin against macrolide-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci (3, 6, 22). The MICs for the macrolide-resistant strains were similar, irrespective of the macrolide resistance mechanism; and the MICs of GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin did not differ significantly. GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin were similarly bactericidal against macrolide-susceptible strains and macrolide-resistant strains with resistance mechanisms caused by presence of the mef(E) gene, alterations in the L4-protein sequence, or mutations in the 23S rRNA sequence. The penicillin G MICs for the clinical strains with mutations in the L4-protein sequence that we have examined thus far were >1.0 μg/ml (3, 22). For the purpose of this study, strains with changes in the L4 protein for which penicillin G MICs were >2.0 μg/ml were selected. However, GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin were bacteriostatic against the three erm(B)-positive strains, even though the MICs for the strains were similar to those for the strains with the mef(E) gene or changes in the L4-protein or 23S rRNA sequence. The bactericidal activity of telithromycin against an erm(B)-positive strain reported previously (27) may represent strain variability. More strains with erm(B) need to be studied before accurate conclusions on this phenomenon may be reached.

In multistep resistance studies, resistance to GW 708408 and telithromycin occurred most slowly. This has previously been shown with telithromycin (6). As described above, macrolide-susceptible parent strains yielded resistant clones with alterations in the sequences of the L4 and L22 proteins and 23S rRNA. All single substitutions and insertions in a conservative amino acid region (amino acid positions 66 to 73) in the L4 protein were detected in mutants exposed to azithromycin and erythromycin. The increase in the MIC for these mutants was eightfold. It is known that changes at amino acid position 93, 94, or 95 in the L4 protein (5, 33) are associated with 8- to 16-fold increases in the erythromycin and telithromycin MICs. Alterations in the L22 protein amino acid sequence have also been reported to be a cause of increased MICs (5, 33). These changes were observed at positions 93, 91, and 83; we observed in this study an alteration in the region between amino acids 80 and 4 which was associated with 7- to 15-fold increases in the MICs of telithromycin, GW 708408, and GW 773546. Macrolide-resistant parents with erm(B) or mef(E) retained these genes, but the MICs for these strains were increased after subculture, mostly without the acquisition of additional ribosomal resistance mechanisms. Only three strains (Table 4, two derivatives of strain 7 and one of strain 12) exposed to telithromycin, GW 708408, and GW 773546 had L22 proteins with mutations at position 96 (Ser replaced by Pro) and position 31 (Arg replaced by Lys) with a concomitant 67-fold increase in the MIC for the strains. A third mutant had a double amino acid change (S96P and E113K), and the MICs for this strain increased eightfold. Mutations in the L4 and L22 proteins and 23S rRNA have recently been described in clinical specimens (5, 16, 22, 28); however, some amino acid alterations in the L4 protein (E13K, insertion 66QS, Q67K, G71C, A73T, K86R, or A10T) or the L22 protein (R31K, insertion 80SEAFAN, R92H, S96P, or E113lK) detected in our study have not yet been shown to occur clinically. Macrolide MICs were high (32 to >64 μg/ml) for resistant mutants with mutations in 23S rRNA (A2058T or A2058G and A2059C). These mutations were observed to be associated with 500 to 4,000 times increases in the erythromycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin, and clindamycin MICs. For two strains a G2057TorA change in the 23S rRNA was associated with an eightfold increase in erythromycin MICs. Mutations in 23S rRNA (G2057T, A2058T or A2058G, and A2059C) have been described, and a correlation between the presence of these mutations and resistance development has been shown (5, 22, 28, 33). Mutation A2058G in 23S rRNA and an additional change in the L4 protein (A10T) were observed in one mutant exposed to GW 773546, but the increase in the MIC was only 15-fold, which is much lower than those described above. It is known that this alteration and an alteration in the L4 protein (S20N) have been associated with macrolide resistance (28).

The incidence of clinically isolated strains with ribosomal protein mutations, such as those that we have described in the present study, is difficult to assess, as probes that can be used to identify these strains have only recently been defined (5, 26). However, clones with mutations in the L4 protein, some of which appear to be clonally related, have been reported from several countries in Central and Eastern Europe (22), and as stated above, clinical strains with mutations in the L22 protein and 23S rRNA have also been described (16, 28). One patient developed a fatal infection caused by a pneumococcus which became resistant due to an L22 mutation while the patient was receiving intravenous azithromycin therapy (21). Similar reports, possibly with different genotypes, may be expected now that the reliable identification of strains with ribosomal protein mutations is possible.

GW 773546, GW 708408, telithromycin, and clindamycin less frequently selected for spontaneous resistance in macro-lide-susceptible strains by single-step selection. In the macro-lide-resistant strains, all compounds tested selected for resistance at similar rates. Resistant clones whose parent strains were susceptible and in which mutations were selected in single steps had no alterations in the L4 protein or 23S rRNA. Three clones selected in single steps with telithromycin and the two new macrolides had an alteration in the L22 protein (A97D). Alterations between amino acids 80 and 97 in the L22 protein were only found by multi- and single-step analyses with GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin (Table 4).

GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin had long PAEs (from 2.4 to 9.8 h). The PAEs of telithromycin and all the other compounds tested in this study are similar to those reported previously (7, 12).

In summary, GW 773546 and GW 708408 were very active, according to their MICs and the results of time-kill studies, against macrolide-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci. Their activities were similar to that of telithromycin; and GW 773546, GW 708408, and telithromycin were bactericidal against all strains tested except those that carried erm(B). GW 708408 and telithromycin selected for resistant strains less frequently than GW 773546, erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin in single-step and multistep selection tests. Resistance among the selected mutants was caused by changes in the sequence of the L4 or L22 ribosomal protein or 23S rRNA. However, some new mutations were found in the L4 and L22 proteins. All compounds tested were found to have long PAEs. Single-step analysis revealed that GW 708408, GW 773546, and telithromycin selected for resistant clones less frequently than the other compounds used in the study. The results of this in vitro study need to be interpreted together with the results of experimental animal and pharmacokinetic and pharmcodynamic studies.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from GlaxoSmithKline Laboratories as part of a joint collaboration with PLIVA Research Laboratories, Zagreb, Croatia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appelbaum, P. C. 1992. Antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae—an overview. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:77-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Block, S., C. J. Harrison, J. A. Hedrick, R. D. Tyler, R. A. Smith, E. Keegan, and S. A. Chartrand. 1995. Penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in acute otitis media: risk factors, susceptibility patterns and antimicrobial management. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 14:751-759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bozdogan, B., P. C. Appelbaum, L. M. Kelly, D. B. Hoellman, A. Tambic-Andrasevic, L. Drukalska, W. Hryniewicz, H. Hupkova, M. R. Jacobs, J. Kolman, M. Konkoly-Thege, J. Miciuleviciene, M. Pana, L. Setchanova, J. Trupl, and P. Urbaskova. 2003. Activity of telithromycin and seven other agents against 1034 pediatric Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates from ten Central and Eastern European centers. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 9:653-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breiman, R. F., J. C. Butler, F. C. Tenover, J. A. Elliott, and R. R. Facklam. 1994. Emergence of drug-resistant pneumococcal infections in the United States. JAMA 271:1831-1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canu, A., B. Malbruny, M. Coquemont, T. A. Davies, P. C. Appelbaum, and R. Leclercq. 2002. Diversity of ribosomal mutations conferring resistance to macrolides, clindamycin, streptogramin, and telithromycin in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:125-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies, T. A., B. E. Dewasse, M. R. Jacobs, and P. C. Appelbaum. 2000. In vitro development of resistance to telithromycin (HMR 3647), four macrolides, clindamycin, and pristinamycin in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:414-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies, T. A., L. M. Ednie, D. B. Hoellman, G. A. Pankuch, M. R. Jacobs, and P. C. Appelbaum. 2000. Antipneumococcal activity of ABT-773 compared to those of 10 other agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1894-1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoban, D., K. Waites, and D. Felmingham. 2003. Antimicrobial susceptibility of community-acquired respiratory tract pathogens in North America in 1999-2000: findings of the PROTEKT surveillance study. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 45:251-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ioannidou, S., P. T. Tassios, L. Zachariadou, Z. Salem, M. Kanelopoulou, S. Kanavaki, G. Chronopoulou, N. Petropoulou, M. Foustoukou, A. Pangalis, E. Trikka-Graphakos, E. Papafraggas, and A. C. Vatopoulos. 2003. In vitro activity of telithromycin (HMR 3647) against Greek Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus pneumoniae clinical isolates with different macrolide susceptibilities. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 9:704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs, M. R. 1992. Treatment and diagnosis of infections caused by drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:119-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobs, M. R., and P. C. Appelbaum. 1999. Streptococcus pneumoniae: activity of newer agents against penicillin-resistant strains. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 1:13-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs, M. R., S. Bajaksouzian, and P. C. Appelbaum. 2003. Telithromycin post-antibiotic and post-antibiotic sub-MIC effects for 10 gram-positive cocci. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:809-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs, M. R., S. Bajaksouzian, A. Zilles, G. Lin, G. A. Pankuch, and P. C. Appelbaum. 1999. Susceptibilities of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae to 10 oral antimicrobial agents based on pharmacodynamic parameters: 1997 U.S. surveillance study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1901-1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs, M. R., D. Felmingham, P. C. Appelbaum, R. N. Grueneberg, and the Alexander Project Group. 2003. The Alexander Project 1998-2000: susceptibility of pathogens isolated from community-acquired respiratory tract infection to commonly used antimicrobial agents. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:229-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohno, S., D. Hoban, and the Protekt Surveillance Study Group. 2003. Comparative in vitro activity of telithromycin and beta-lactam antimicrobials against bacterial pathogens from community-acquired respiratory tract infections: data from the first year of PROTEKT (1999-2000). J. Chemother. 15:335-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozlov, R., T. M. Bogdanovitch, P. C. Appelbaum, L. Ednie, L. S. Stratchounski, M. R. Jacobs, and B. Bozdogan. 2002. Antistreptococcal activity of telithromycin compared with seven other drugs in relation to macrolide resistance mechanisms in Russia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2963-2968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leclercq, R., L. Nantas, C. J. Soussy, and J. Duval. 1992. Activity of RP 59500, a new parenteral semisynthetic streptogramin, against staphylococci with various mechanisms of resistance to macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin antibiotics. J. Antimicrob Chemother. 30(Suppl. A):67-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mason, E. O., Jr., L. B. Lamberth, N. L. Kershaw, B. L. Prosser, A. Zoe, and P. G. Ambrose. 2000. Streptococcus pneumoniae in the USA: in vitro susceptibility and pharmacodynamic analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45:623-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDougal, L. K., R. Facklam, M. Reeves, S. Hunter, J. M. Swenson, B. C. Hill, and F. C. Tenover. 1992. Analysis of multiply antimicrobial-resistant isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae from the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:2176-2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munoz, R., J. M. Musser, M. Crain, D. E. Briles, A. Marton, A. J. Parkinson, U. Sorensen, and A. Tomasz. 1992. Geographic distribution of penicillin-resistant clones of Streptococcus pneumoniae: characterization by penicillin-binding protein profile, surface protein A typing, and multilocus enzyme analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:112-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Musher, D. M., M. E. Dowell, V. D. Shortridge, R. K. Flamm, J. H. Jorgensen, P. L. le Magueres, and K. L. Krause. 2002. Emergence of macrolide resistance during treatment of pneumococcal pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 346:630-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagai, K., P. C. Appelbaum, T. A. Davies, L. M. Kelly, D. B. Hoellman, A. T. Andrasevic, L. Drukalska, W. Hryniewicz, M. R. Jacobs, J. Kolman, J. Miculeviciene, M. Pana, L. Setchanova, M. K. Thege, H. Hupkova, J. Trupl, and P. Urbaskova. 2002. Susceptibilities to telithromycin and six other agents and prevalence of macrolide resistance due to L4 ribosomal protein mutation among 992 pneumococci from 10 Central and Eastern European countries. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:371-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagai, K., T. A. Davies, G. A. Pankuch, B. E. DeWasse, M. R. Jacobs, and P. C. Appelbaum. 2000. In vitro selection of resistance to clinafloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and trovafloxacin in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2740-2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 6th ed.; approved standard. NCCLS publication M7-A6. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 25.Pankuch, G. A., M. R. Jacobs, and P. C. Appelbaum. 1994. Study of comparative antipneumococcal activities of penicillin G, RP 59500, erythromycin, sparfloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and vancomycin by using time-kill methodology. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:2065-2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pankuch, G. A., S. A. Juenemann, T. A. Davies, M. R. Jacobs, and P. C. Appelbaum. 1998. In vitro selection of resistance to four β-lactams and azithromycin in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2914-2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pankuch, G. A., M. A. Visalli, M. R. Jacobs, and P. C. Appelbaum. 1998. Susceptibilities of penicillin- and erythromycin-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci to HMR 3647 (RU 66647), a new ketolide, compared with susceptibilities to 17 other agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:624-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reinert, R. R., A. Wild, P. Appelbaum, R. Lütticken, M. Y. Cil, and A. Al-Lahham. 2003. Ribosomal mutations conferring resistance to macrolides in Streptococcus pneumoniae clinical strains isolated in Germany. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2319-2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez, M. L., K. K. Flint, and R. N. Jones. 1993. Occurrence of macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin resistances among staphylococcal clinical isolates at a university medical center. Is false susceptibility to new macrolides and clindamycin a contemporary clinical and in vitro testing problem? Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 16:205-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schito, A. M., G. C. Schito, E. Debbia, G. Russo, J. Linares, E. Cercenado, and E. J. Bouza. 2003. Antibacterial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae from Italy and Spain: data from the PROTEKT surveillance study, 1999-2000. J. Chemother. 15:226-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sutcliffe, J., T. Grebe, A. Tait-Kamradt, and L. Wondrack. 1996. Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2562-2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ubukata, K., S. Iwata, and K. Sunakawa. 2003. In vitro activities of new ketolide, telithromycin, and eight other macrolide antibiotics against Streptococcus pneumoniae having mefA and ermB genes that mediate macrolide resistance. J. Infect. Chemother. 9:221-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walsh, F., J. Willcock, and S. Amyes. 2003. High-level resistance in laboratory-generated mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:345-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]