Abstract

Several lines of evidence suggest that kinetochores are organizing centers for the spindle checkpoint response and the synthesis of a “wait anaphase” signal in cases of incomplete or improper kinetochore-microtubule attachment. Here we characterize Schizosaccharomyces pombe Bub3p and study the recruitment of spindle checkpoint components to kinetochores. We demonstrate by chromatin immunoprecipitation that they all interact with the central domain of centromeres, consistent with their role in monitoring kinetochore-microtubule interactions. Bub1p and Bub3p are dependent upon one another, but independent of the Mad proteins, for their kinetochore localization. We demonstrate a clear role for the highly conserved N-terminal domain of Bub1p in the robust targeting of Bub1p, Bub3p, and Mad3p to kinetochores and show that this is crucial for an efficient checkpoint response. Surprisingly, neither this domain nor kinetochore localization is required for other functions of Bub1p in chromosome segregation.

Transit round the cell cycle is regulated by several checkpoint controls (21). These act as surveillance systems that detect any defect or incompletion in a particular process, such as DNA replication or spindle assembly, and act to delay cell cycle progression until the defects are corrected. The spindle checkpoint monitors kinetochore-microtubule attachment and the tension produced on sister kinetochores when they are attached to opposite spindle poles (37, 53), and it inhibits anaphase onset until all sisters have achieved stable bio-orientation (see references 12 and 44 for recent reviews). The first spindle checkpoint proteins were identified through genetic screens for the mad and bub mutants in budding yeast (27, 36). Later, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mps1 kinase was shown to have spindle checkpoint function, in addition to its role in spindle pole duplication (67). These checkpoint proteins are conserved from yeast to human (41), as is their target, Cdc20 (Slp1 in fission yeast) (28, 34). Cdc20 is a cofactor for the anaphase-promoting complex cyclosome (48), which is a mitotic E3 ubiquitin ligase that polyubiquinates the key regulators of the metaphase-to-anaphase transition, securin (Pds1/Cut2 in yeast) and cyclin B (Clb2/Cdc13). Certain checkpoint proteins (Mad2, Mad3/BubR1, and Bub3) have been found to complex directly with Cdc20 and thereby inhibit it (14, 19, 28, 34, 42, 57, 59). Structural studies are starting to shed light on the precise molecular mechanism of checkpoint protein inhibition of Cdc20 (38, 56), but how and where such anaphase inhibitors are formed remain unclear (16, 57).

Classic cell biological experiments have argued that the kinetochore is the source of the “wait anaphase signal” (53), and many studies have revealed that mutation or depletion of specific kinetochore proteins can inhibit the spindle checkpoint response (17, 31, 39, 40, 68). However, it has not been proven that kinetochore targeting of checkpoint components is crucial for a mitotic arrest, and it has even been argued that checkpoint signaling can continue in the absence of functional kinetochores (15, 51). Vertebrate studies have shown that all of the Mad and Bub proteins are recruited to kinetochores in mitosis, and fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments have demonstrated that the interaction of checkpoint proteins with kinetochores is extremely dynamic, with Mad2p having a half-life of around 20 s on kinetochores (25). Thus, these proteins undergo a constant cycle of targeting to and removal from kinetochores during mitosis.

Functional studies of checkpoint proteins can be complicated by the fact that they can have additional mitotic roles. In budding yeast the Bub3 and Bub1 proteins have additional chromosome segregation functions, as deletion of these genes leads to significantly higher rates of chromosome loss than deletion of the MAD genes (66). The nature of these additional Bub1/Bub3 functions is unclear, and it is not known if they are evolutionarily conserved, although vertebrate Bub1 RNA interference studies have recently led to the proposal that Bub1 plays a role in chromosome congression (32).

In this work we used Schizosaccharomyces pombe as a model system for the spindle checkpoint. This enabled us to do simple yet powerful genetic experiments in an organism with very good cytology. The fission yeast centromeres are an excellent model of those of higher eukaryotes, as their kinetochores bind multiple microtubules (13), are flanked by large regions of repetitive heterochromatin, and have epigenetic characteristics (for reviews, see references 33 and 49). Fission yeast Mad1 (29), Mad2 (23, 34), Mad3 (42), Bub1 (6), and Mph1 (22) have all been identified and shown to have conserved their checkpoint function. Bub1p has important roles in normal, unperturbed mitoses, as bub1 mutants have significant rates of chromosome loss and lagging chromosomes and fail to maintain the diploid state (6). Bub1p also has crucial meiotic functions (7) and is a Cdc2 substrate (64, 69).

Here we report our identification of the fission yeast Bub3 protein and study its genetic and biochemical interactions with the other checkpoint proteins. We demonstrate that all of the Mad proteins, Bub1p, and Bub3p associate with fission yeast kinetochores and, by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), that they all interact with the central domain of centromeres. We carried out a thorough study of the dependencies that the checkpoint proteins have upon one another for their kinetochore recruitment. The Bub1 and Bub3 proteins were found to be interdependent for localization, and we show that an N-terminal region of Bub1 is required for the enrichment of Bub1p, Bub3p, and Mad3p on kinetochores during a checkpoint arrest. However, careful examination of the bub1Δ28-160 and bub3 mutants suggests that Bub1p has additional chromosome segregation functions that are not Bub3 dependent. This bub1 mutant is the first clear separation-of-function allele for a spindle checkpoint protein. It demonstrates that while enrichment of the checkpoint proteins at kinetochores is crucial for a spindle checkpoint arrest, it is not required for other chromosome segregation functions of the Bub1 kinase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and yeast strains.

All strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Media, transformations, and genetic techniques were essentially as described elsewhere (43). YE6S refers to yeast extract medium supplemented with Leu, Ura, Ade, His, Lys, and Arg (2). Benomyl (30-mg/ml stock in dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) was added to boiling YES medium and thiabendazole (10-mg/ml stock in DMSO) was added to a final concentration of 15 μg/ml to minimal medium, while 25 to 75 μg of carbendazim (CBZ; Aldrich; 5-mg/ml stock in DMSO) was used in liquid cultures. Hydroxyurea (HU; 12 mM) was used to synchronize cultures in S phase.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Yeast strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| KP277 | h− ura4-D18 leu1-32 his3-D arg3-D4 | |

| KP106 | h− bub3Δ::ura4+ leu1-32 ade6 ura4-D18 | |

| AE247 | h− mad1Δ::ura4+ leu1 | T. Matsumoto |

| DM075 | h− mad2Δ::ura4+ | T. Matsumoto |

| DM001 | h− mad3Δ::ura4+ | |

| KP175 | h− mph1Δ::ura4+ | S. Sazer |

| KP101 | h+ bub3-Myc::G418 ura4-D18 leul-32 | |

| KP200 | h− bub3-Myc::G418 bub1 HA mad3-GFP::his3+ nda3KM311 | |

| KP258 | h+ bub3-GFP::his3+ ura4-D18 leu1-32 | |

| KP333 | h− bub3-GFP::his3+ bub1Δ::ura4+ | |

| KP330 | h− bub3-GFP::his3+ mad1Δ::ura4+ | |

| KP331 | h− bub3-GFP::his3+ mad2Δ::ura4+ | |

| KP332 | h− bub3-GFP::his3+ mad3Δ::ura4+ | |

| KP334 | h− bub3-GFP::his3+ mph1Δ::ura4+ | |

| KP187 | h+ mad1-GFP::his3+ | |

| KP182 | h− mad1-GFP::his3+ bub1Δ::ura4+ | |

| KP184 | h− mad1-GFP::his3+ bub3Δ::ura4+ | |

| KP180 | h− mad1-GFP::his3+ mad2Δ::ura4+ | |

| KP181 | h− mad1-GFP::his3+ mad3Δ::ura4+ | |

| KP186 | h− mad1-GFP::his3+ mph1Δ::ura4+ | |

| KP252 | h+ mad2-GFP::his3+ | |

| DM059 | h+ mad3-GFP::his3+ | |

| KP156 | h− mad1-GFP::his3+ nda3 | |

| RV001 | h− mad2-GFP::his3+ nda3 | |

| DM076 | h− mad3-GFP::his3+ nda3 | |

| RV002 | h− bub3-GFP::his3+ nda3 | |

| KP379 | h− Ch16 (bub1Δ::ura4) | |

| KP380 | h− mad3Δ::ura4 Ch16 (bub1Δ::ura4) | |

| KP378 | h− bub3Δ::ura4 Ch16 (bub1Δ::ura4) | |

| KP349 | h+lys1 ura4 leu1 ade6-M210 cen2D107(::Kan-ura4-lacO) his7::lacI-GFP | Y. Hiraoka |

| KP383 | h−bub3Δ::ura4 cen2D107(::Kan-ura4-lacO) his7::lacI-GFP | |

| KP384 | h−mad3Δ::ura4 cen2D107(::Kan-ura4-lacO) his7::lacI-GFP | |

| KP382 | h−Mad3-GFP::his3+Cdc11-CFP::G418 | |

| KP381 | h−Bub3-GFP::his3+Cdc11-CFP::G418 | |

| JPJ1660 | h+bub1-K762M | |

| JPJ1821 | h+bub1 Δ28-160 | |

| 1297 | h−ade6-210 his1-102 leu1-32 ura4-DS/E | R. Allshire |

| 4536 | h+sim4-193 TM1::arg3 TM3::ade6 otr2::ura4 his3tel1L ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4D18 arg3-D4 his3-D1 | R. Allshire |

| 2221 | h−TM1(NcoI)::arg3 ade6-210 arg3-D4 his3-D1 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | R. Allshire |

| yVV23 | h+bub1-GFP::his3+his3−arg− | |

| yVV29 | h+ bub1-GFP::his3+ mph1Δ::ura4+ | |

| yVV30 | h−bub1-GFP::his3+bub3Δ::ura4+ | |

| yVV34 | h− bub1-GFP::his3+ mad1Δ::ura4+ | |

| yVV35 | h− bub1-GFP::his3+ mad3Δ::ura4+ | |

| yVV39 | h−bub1-GFP::his3+mad2Δ::ura4+ | |

| yVV40 | h− bub1-K762M bub3-Myc::G418 | |

| yVV41 | h− bub1-GFP::his3+ bub3-Myc::G418 | |

| yVV192 | h− bub1Δ::ura4+ his3− arg3− | |

| yVV194 | h− mad2Δ::ura4+ his3− arg3− | |

| yVV195 | h− mph1Δ::ura4+ his3− arg3− | |

| yVV228 | h− bub1Δ::ura4+ TM1(NcoI)::arg3 | |

| yVV229 | h− mad2Δ::ura4+ TM1(NcoI)::arg3 | |

| yVV230 | h− mph1Δ::ura4+ TM1(NcoI)::arg3 | |

| yVV241 | h− bub1Δ28-160 bub3-Myc::G418 | |

| yVV273 | h− bub1-K762M bub3Δ::ura4+ | |

| yVV276 | h− bub1-Δ28-160-GFP::his3+ arg3− | |

| yVV283 | h− bub1-Δ28-160 mad3-GFP::his3+ bub3-Myc::G418 | |

| yVV206 | h− cdc25 Bub1-GFP::his3+ cut12-CFP::G418 | |

| yVV383 | h− cdc25 Bub1Δ28-160-GFP::his3+ cut12-CFP::G418 | |

| yVV400 | h− bub1Δ::ura4 cen2D107(::Kan-ura4-lacO) his7::lac1-GFP | |

| yVV398 | h− bub1-K762M cen2D107(::Kan-ura4-lacO) his7::lac1-GFP | |

| yVV401 | h−bub1Δ28-160::ura4 cen2D107(::Kan-ura4-lacO) his7::lac1-GFP |

Rate-of-death assays, lagging chromosome analyses, and Ch16 minichromosome loss assays were performed as previously described (6). Missegregation of cen2-GFP (35, 70) was assayed in binucleate cells in log-phase cycling cultures, either in live cells or after brief methanol fixation.

pMad2/pMph1 arrests.

Cells were grown to log phase in minimal medium lacking leucine and containing thiamine (5 μM). Cells were washed three times and resuspended in medium lacking thiamine to induce expression from the nmt promoter. Cells were then typically grown for 16 h before harvesting and analysis of mitotic arrest (22, 23).

Identification and disruption of the Bub3 ORF.

The putative bub3+ open reading frame (ORF) was identified by BLAST searching the S. pombe genome project data set with the S. cerevisiae BUB3 DNA sequence. A ura4+-marked bub3 deletion strain (KP104) was constructed using sequence information of the 5′ and 3′ flanks of the putative bub3+ ORF and the PCR-based gene targeting method described elsewhere (5). After sporulation, correctly targeted gene disruptions were identified by PCR amplification over both the 5′ and 3′ junctions.

DNA manipulations.

Sequencing was carried out with an Applied Biosystems BigDye sequencing kit. To tag Bub3 with green fluorescent protein (GFP), bub3+ was PCR amplified and cloned into the KpnI/SalI sites of plasmid pDM084 (42). Homologous recombination was confirmed by PCR amplification over the junctions, followed by immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibodies (Molecular Probes). The C-terminal 13× Myc tag (KP101) was introduced by PCR (5), and G418-resistant strains were screened by Western blotting and PCR. These strains are not benomyl sensitive (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material), indicating that these Bub3p constructs are fully functional. Mad1-GFP, Mad2-GFP, and Bub1-GFP were also generated using pDM084-derived constructs.

Construction of bub1 mutants (K762 M and Δ28-160).

A 3′ fragment of BUB1 was PCR amplified with primers MD FW (CCGGTACCCCGACGCTAATAAATCCCCTAG) and MD RV (CTCTTCAGAAACGTGCAATGTG) and cloned into the pGEMT-Easy vector (Promega), resulting in plasmid pVV2. The resultant constructs were sequenced and shown to be void of mutations. pVV2 was further mutagenized using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with the primers K762 M FW (CTAAGCTTTTTGCTTTAATGATTGAGACACCACCTTCG) and K762 M RV (CGAAGGTGGTGTCTCAATCATTAAAGCAAAAAGCTTAG) to give the plasmid pVV2.1, where codon 762 of bub1 is mutagenized to ATG, as verified by sequencing. The mutation was then transferred to pUR19bub1+ (6) to give pUR19bub1-K762 M. To generate bub1Δ28-160, the 3,769-bp BamHI/SphI bub1+ fragment was cloned into pUC18. The resulting plasmid, pUC18bub1+, was digested with XhoI and religated after Klenow treatment to give pUC18bub1Δ28-160. Constructs were checked by sequencing the regions of interest.

bub1 strain construction.

The BamH1-Sph1 fragment from either pSKbub1K762 M or pSKbub1Δ28-160 was cotransformed with an episomal LEU2 plasmid into a bub1Δ::ura4+ strain (JPJ393 [6]). Leu+ fluoroorotic acid-resistant clones were selected and analyzed for correct integration by PCR and Western blotting. The LEU2 episomal plasmid was then lost from the cells.

Coimmunoprecipitations.

Coimmunoprecipitations were carried out as previously described (42). Bub3-Myc was immunoprecipitated with 9E10-coupled agarose (Santa Cruz), and Bub1-HA was immunoprecipitated with 3F10-coupled agarose (Roche).

Polyclonal anti-Bub1 antibodies were generated in both rabbits and sheep using the first 190 residues of Bub1p fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST) as antigen (pKHPB16P). These sera were affinity purified as described previously (20) using Bub1-GST coupled to Affigel 10 (Bio-Rad).

Imaging.

Live-cell imaging was typically performed in minimal media, often with the addition of 0.5% low-melting-point agarose. Cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) and green fluorescent protein (GFP) imaging were also performed after brief methanol fixation (30 to 60 s). For immunofluorescence, cells were fixed for 2 to 20 min by the addition of freshly prepared paraformaldehyde solution (3.7%) and processed as described previously (6). Primary antibodies used were sheep anti-Cnp1 (used at 1/1,000; kindly provided by Barbara Mellone and Robin Allshire), mouse anti-TAT1 (used at 1/50; a gift from Keith Gull), and rabbit anti-GFP (used at 1/1,000; Molecular Probes). All secondary antibodies were Alexa coupled and used at 1/2,000 (Molecular Probes). Imaging was performed using an Intelligent Imaging Innovations (3i) Marianas system. This system employs a Zeiss Axioplan fluorescence microscope, a CoolSNAP HQ charge-coupled device camera (Photometrics), and Slidebook software (3i).

Chromatin immunoprecipitations were carried out as described elsewhere (50), incorporating the following modifications. nda3 strain cells were arrested at 18°C for 8 h and then fixed with paraformaldehyde at 18°C for 30 min. Cells were spheroplasted at 108 cells/ml in PEMS [100 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (pH 7), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.2 M sorbitol] plus 0.4 mg of Zymolyase 100T/ml for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were then washed twice in PEMS, and pellets were frozen at −20°C. Protein A or protein G Dynabeads (Dynal) were coated with 0.25 mg of anti-GFP antibody (Molecular Probes), or anti-Cnp1 antibody, by incubating in phosphate-buffered saline-0.1% Triton X-100 for 1 h at 4°C and then washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline-0.1% Triton X-100 and once with lysis buffer before being used to immunoprecipitate the protein from the crude lysate without preclearing. Quantitation was performed as described elsewhere (50).

Silencing assays, for both the central core and outer repeat regions, were carried out as previously described (50).

RESULTS

S. pombe Bub3p is a spindle checkpoint component.

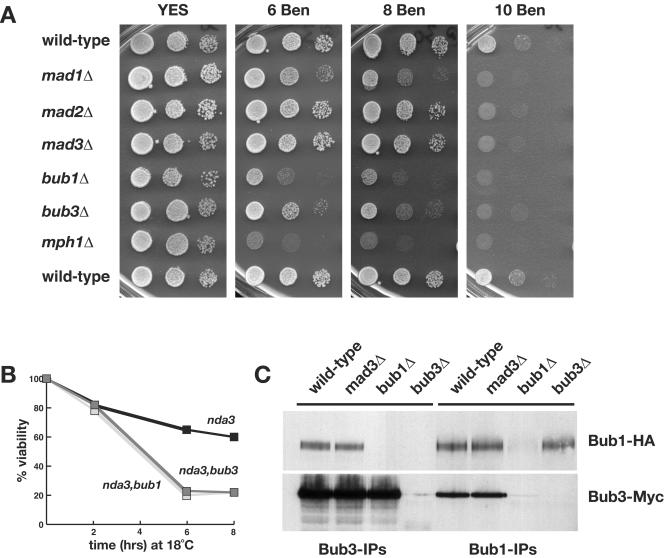

Bub3 has been argued to be an important player in the recruitment of checkpoint proteins to kinetochores (18, 60). We identified the Bub3 homologue in the fission yeast genome sequencing project. Fission yeast bub3+ (SPAC23H3.08c) is predicted to encode a 36-kDa protein that is 24% identical (plus 35% similar) to budding yeast Bub3p and 35% identical (plus 34% similar) to its human homologue. To confirm that fission yeast Bub3p has conserved its spindle checkpoint function, we constructed a gene knockout in which the bub3+ ORF was replaced with the ura4+ selectable marker. Figure 1A shows that this haploid strain was sensitive to the microtubule-depolymerizing drug benomyl. It was more sensitive to benomyl than either mad2 or mad3 mutants, had a similar sensitivity to that of mad1, but was less sensitive than either bub1 or mph1 checkpoint mutants.

FIG. 1.

Fission yeast Bub3p is a spindle checkpoint component that interacts with both Bub1p and Mad3p. (A) The indicated strains were tested for benomyl sensitivity. bub3Δ cells were more sensitive to antimicrotubule drugs (benomyl) than mad2 or mad3 mutants, but not as sensitive as bub1 or mph1 mutants. (B) nda3, nda3 bub1, and nda3 bub3 strains were grown to log phase at 30°C and then shifted to 18°C. At the indicated time points, samples were taken, diluted in water, and plated on YES plates. After 3 days of growth at 30°C, the number of colonies growing were counted. (C) Bub proteins were immunoprecipitated from yeast extracts, immunoblotted, and detected using antihemagglutinin (anti-HA; for Bub1) and anti-Myc (for Bub3) antibodies. Bub1p and Bub3p were clearly coimmunoprecipitated from wild-type and mad3Δ extracts.

We were surprised at this difference in benomyl sensitivity between the bub1Δ and bub3Δ strains, because in budding yeast bub1 and bub3 mutants have very similar phenotypes and are thought to function together in all of their checkpoint and chromosome segregation roles (27, 66). To compare the fission yeast bub mutants more carefully, we measured their chromosome loss rates in quantitative assays that determined the efficiency of overall mitotic function. bub1Δ mutants have relatively high rates of chromosome loss in mitosis: using a 530-kb linear marker chromosome, Ch16, bub1Δ strains display 3.5% chromosome loss per division (a 70-fold increase over the wild-type loss rate) (6). Consistent with their lower sensitivity to benomyl, we found that bub3Δ mutants displayed only 0.2% Ch16 loss per division, while mad3Δ mutants had <0.1% Ch16 loss per division (Table 2). We also monitored the segregation of GFP-marked chromosome 2. Imaging of binucleate cells confirmed that bub1Δ strains had far higher rates of chromosome missegregation than either bub3Δ or mad3Δ strains. In 5.3% of binucleate bub1Δ cells, both copies of chromosome 2 were observed in the same daughter nucleus (2.0, rather than 1.1 segregation), whereas this was observed in <0.2% of bub3Δ or mad3Δ binucleate cells (Table 2). Thus, in three independent assays, fission yeast bub3Δ mutants displayed a phenotype that was significantly weaker than that of bub1Δ cells.

TABLE 2.

Chromosome missegregation assay results

| Strain | % (no. tested)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| cen2-GFPa | Ch16 lossb | Lagging chromosomesc | |

| Wild type | 0 (510) | 0 (2,100) | 0.3 (350) |

| mad3Δ | 0 (521) | <0.1 (3,340) | 0 (300) |

| bub3Δ | <0.2 (1,362) | 0.2 (9,750) | 2.4 (505) |

| bub1Δ | 5.3 (1,002) | 3.5 | 17.5 (588) |

| bub1Δ28-160 | 0.8 (1,062) | ND | 0.5 (304) |

| bub1 (kinase dead) | 2.6 (900) | ND | 10.1 (365) |

Missegregation of GFP-marked chromosome 2 (2.0 rather than 1.1) was scored as the percentage of binucleate cells in log-phase cultures.

Ch16 loss was scored as the percentage of half-sectored (red/white) colonies in the colony sectoring assay. Value for bub1Δ Ch16 loss is from reference 7. ND, not determined.

Lagging chromosomes were scored in log-phase cultures as the percentage of anaphase cells displaying lagging chromosomes (as described in reference 7).

bub3Δ strains displayed no abnormalities in spindle or general microtubule structure (data not shown). To test whether the benomyl sensitivity of bub3Δ was due to a defective spindle checkpoint, we constructed a double mutant with the cold-sensitive tubulin mutant (bub3Δ nda3-KM311). At 18°C the nda3 single mutant arrests in mitosis with hypercondensed chromosomes (24). In this mutant, there is a complete lack of kinetochore-microtubule attachment, due to the absence of spindle microtubules, and the spindle checkpoint is activated. The bub3Δ nda3 double mutant was defective in this checkpoint arrest: viability was lost rapidly at 18°C (Fig. 1B), and cytological analysis revealed the classic Cut (cells untimely torn) phenotype as cells underwent septation without prior nuclear division (data not shown). We conclude that while fission yeast Bub3p is not essential for growth or structural spindle or microtubule functions, it is an important component of the spindle checkpoint.

Budding yeast and vertebrate Bub3p have been shown to bind to Bub1p and to the related proteins Mad3p and BubR1 (9, 19, 60). Our labs has previously reported that Bub3p interacts with fission yeast Mad3p (42), and here we show that Bub3p also coimmunoprecipitates with Bub1p (Fig. 1C). The Bub1p-Bub3p complex was unaffected by the absence of Mad3p in cells, and we found no clear evidence of posttranslational modification of Bub3p, nor of regulation of the abundance of Bub3p-Bub1p complexes through the cell cycle (data not shown).

S. pombe Rae1p does not have a spindle checkpoint function.

In budding yeast, bub1Δ and bub3Δ strains have very similar phenotypes (66). Why is this not the case in fission yeast? One possibility is that fission yeast Bub3p is not required for all Bub1p functions. Recent mouse studies have argued that a subset of Bub3 spindle checkpoint functions can be performed by the related Rae1 protein (4). In particular, Rae1 was shown to interact with Bub1 but not with BubR1 (65). Fission yeast Rae1p is essential for growth and has been shown to have key roles in nuclear import and export (71). We tested whether the temperature-sensitive rae1-167 mutant also had phenotypes suggestive of spindle checkpoint defects. The rae1 mutant was not benomyl sensitive (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material); indeed, it appeared to be somewhat resistant to benomyl at its semipermissive temperature of 32°C. We have been unable to find any evidence of complexes formed between Rae1p and spindle checkpoint proteins. Even when epitope-tagged Rae1p was overexpressed in a bub3Δ strain, to avoid any competition with endogenous Bub3p, we were unable to coimmunoprecipitate it with either Bub1p or Mad3p (data not shown). Finally, attempts to suppress the bub3Δ strain by the overexpression of Rae1p were unsuccessful (see Fig. S1C in the supplemental material). We conclude that Rae1p does not have a spindle checkpoint role in fission yeast. Indeed, we believe that the bub3Δ strain has most likely lost all spindle checkpoint function and that Bub1p has additional, noncheckpoint functions that are Bub3 independent (see below).

Bub3p is recruited to kinetochores in a normal mitosis.

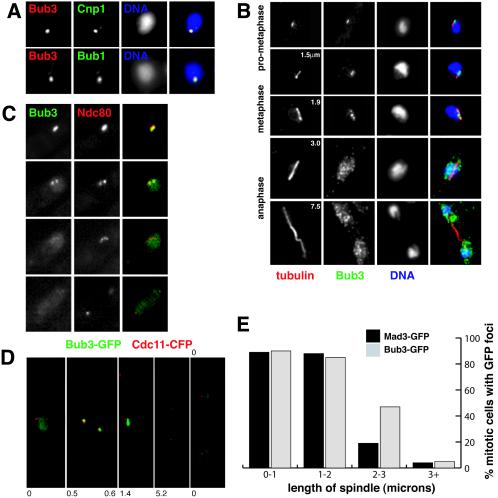

Figure 2 describes our fixed and live-cell analyses of the localization of fission yeast Bub3p. Cnp1 is the fission yeast homologue of CENP-A (58), and Bub3p's checkpoint partner Bub1p has been previously shown to localize to kinetochores during mitosis (6). In fixed, early mitotic cells bright Bub3-GFP foci clearly colocalized with both of these kinetochore markers (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Bub3p localizes to kinetochores during mitosis. (A) Bub3-GFP colocalizes with kinetochore markers Cnp1 and Bub1 in fixed early mitotic cells. (B) Log-phase cells expressing Bub3-GFP were fixed and labeled with anti-GFP antibodies and TAT1 (antitubulin) antibodies, and the DNA was stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole. The numbers in the left panels indicate the lengths of the microtubule spindles (in micrometers). Bub3-GFP was detected as punctate foci associated with short spindles in cells early in mitosis, but it was diffuse in anaphase cells. The GFP speckles observed in anaphase cells are thought to be fixation artifacts (see text). (C) In living cells, the colocalization of bright Bub3-GFP foci and Ndc80-CFP is apparent early in mitosis. As cells reach metaphase and then enter anaphase, the Bub3 signal becomes much fainter. (D) Cells containing Bub3-GFP and the spindle pole marker Cdc11-CFP were preincubated with HU to synchronize them in S phase, and then they were washed and released into fresh medium. These images were taken from cells after brief methanol fixation. The number indicates the length of the spindle, as defined by the distance between two Cdc11 foci (0 indicates an interphase cell). (E) Quantitation of the fraction of the mitotic cells, with specific spindle lengths, that displayed clear Bub3/Mad3-GFP foci in the experiments shown in panel D. Almost all early mitotic cells displayed clear checkpoint foci.

Is Bub3p at kinetochores throughout mitosis? In fixed mitotic cells with short pro-metaphase/metaphase spindles (<3 μm long [45]), we observed bright foci of Bub3-GFP closely associated with the microtubules (Fig. 2B). Two or three spots were typically seen, which were associated with DNA and tended to be near the center of the spindle. In anaphase cells (spindle >3 μm long), bright Bub3-GFP foci could no longer be seen and the protein appeared to be located throughout the nucleoplasm in speckles (see below). Live-cell imaging showed that the Ndc80-CFP kinetochore marker and Bub3-GFP colocalized early in mitosis (Fig. 2C), and bright Bub3-GFP foci were usually observed in cells with two closely spaced Cdc11-CFP-labeled spindle poles but not in cells with spindles >3 μm long (Fig. 2D and E). This confirmed that Bub3-GFP is recruited to kinetochores early in mitosis and that it can only rarely be detected there after anaphase onset. Note that paraformaldehyde fixation of Bub3-GFP followed by anti-GFP immunofluorescence (as in Fig. 2B) led to a punctate nuclear fluorescence in anaphase cells, but these speckles did not specifically associate with kinetochores or microtubules. We believe these speckles to be fixation artifacts, because in live-cell imaging (Fig. 2C) or in GFP-CFP imaging after brief methanol fixation (Fig. 2D) anaphase and interphase cells displayed a more uniform nucleoplasmic staining for Bub3-GFP.

Are fission yeast checkpoint proteins recruited to kinetochores every mitosis, or only in the subset of mitotic cells in which microtubule-kinetochore interactions are perturbed? We imaged cells containing Cdc11-CFP-marked spindle poles and either Bub3-GFP or Mad3-GFP. To enrich for mitotic cells, log-phase cultures were first incubated in HU for 4 h, washed, and then released into rich medium. Most cells entered mitosis 2 to 3 h after release from HU. Random fields of cells were analyzed and mitotic cells, containing two Cdc11-CFP foci, were scored for spindle length and the presence of Bub/Mad-GFP foci (Fig. 2E). A total of 90% of cells with short metaphase spindles (<3 μm in length) contained clear Bub3/Mad3-GFP foci, indicating that both checkpoint proteins are recruited to fission yeast kinetochores early in a normal mitosis. Approximately 10% of cells with short spindles appeared to lack clear Bub3/Mad3-GFP foci. We suggest that these cells had already formed stable kinetochore-microtubule attachments, or they could be cells in which GFP foci were out of focus. In support of this, we always detected Bub3/Mad3-GFP foci in early mitosis during live-cell imaging (data not shown). Fission yeast Bub1p is also recruited to kinetochores every cell cycle (see Fig. 8A, below) (61, 62). Only a few cells containing anaphase spindles (>3 μm in length) had Bub3 or Mad3-GFP foci, and these were typically rather faint and appeared to be associated with spindle poles (data not shown). Thus, Bub3p behaves in a very similar manner to that described for Mad3p (42): it is recruited to and enriched on kinetochores early each mitosis, and the bulk of it dissociates prior to anaphase. Figure 2E shows that Mad3-GFP signals were lost before Bub3-GFP (and Bub1-GFP [see Fig. 8A]). This could reflect the temporal order of loss of different checkpoint proteins from kinetochores during mitosis, but as Mad3-GFP signals are the faintest they may simply be the first to fall below our detection limit.

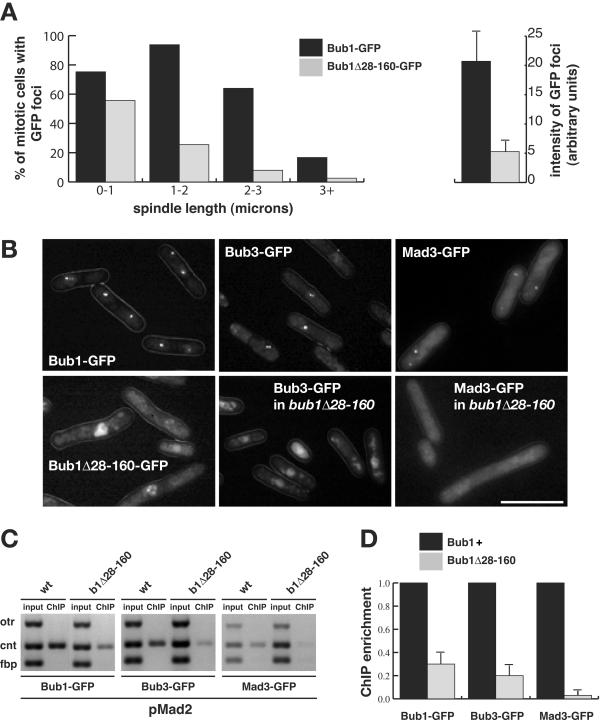

FIG. 8.

Bub1Δ28-160p fails to be efficiently enriched on central core chromatin and fails to recruit Bub3p and Mad3p to kinetochores. (A) Bub1p is recruited to kinetochores every cell cycle. bub1-GFP cdc25 cells were presynchronized in G2 at 36°C and then released at room temperature. Images of mitotic cells were captured after brief methanol fixation, and their spindle length was measured as the distance between two Cut12-CFP foci. Quantitation is displayed as the percentage of mitotic cells, with the defined spindle lengths, that displayed clear Bub1-GFP or Bub1Δ28-160-GFP foci. (B) Imaging of Bub1-GFP, Bub3-GFP, and Mad3-GFP in the indicated strains after their arrest in mitosis by Mad2p overexpression. While Bub1, Bub3, and Mad3 foci were readily detectable in the wild-type cells (70 to 80%) (upper panels), only faint Bub1Δ28-160-GFP foci could be imaged in living cells (∼20%) and Bub3-GFP and Mad3-GFP foci were undetectable in bub1Δ28-160 cells (lower panels). Bar, 10 μm. (C) ChIP demonstrated that there was reduced enrichment of central core DNA with Bub1Δ28-160-GFP and with Bub3-GFP, and almost no enrichment of Mad3-GFP, in bub1Δ28-160 strains that had been arrested by Mad2p overexpression. (D) ChIP quantitation. The DNA gels were scanned, and the enrichment of the ChIP signals, relative to the input, was calculated (50). We then set the enrichment for each protein in wild-type cells to a value of 100%. The reduced enrichment observed for each of the three proteins in the bub1Δ28-160 mutant was plotted as the percentage of this. This experiment was repeated four times, and the error bars show the maximum deviations from the plotted means.

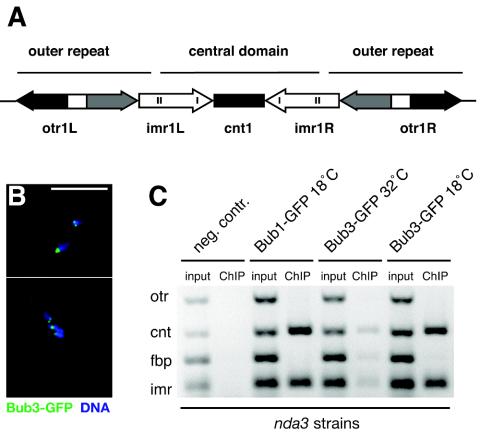

Mad and Bub proteins associate with the central core of centromeres.

The fission yeast centromere is thought to be an excellent model for that of vertebrates and has been subdivided into distinct protein interaction domains, the central domain (central core [cnt] plus innermost repeats [imr]) and the outer repeats (otr) (Fig. 3A) (47, 49). For a detailed analysis of the centromere association of the Mad and Bub proteins, we carried out ChIP from nda3-arrested cells. Figure 3B shows clear foci of Bub3-GFP associated with the hypercondensed chromatin observed in this checkpoint-dependent arrest. Both Bub3-GFP and Bub1-GFP were cross-linked to the central domain of centromere 1 in arrested cells, but we found no enrichment of Bub1-GFP or Bub3-GFP with the otr of centromere 1 (Fig. 3C). We were unable to detect a clear ChIP signal for Bub3-GFP with centromeres in a cycling population of cells. Presumably, this reflected the fact that Bub3p only interacts briefly with kinetochores in an unperturbed mitosis and that metaphase cells are a small percentage of the cycling population (∼3%).

FIG. 3.

Bub3p interacts with the central core chromatin of fission yeast cen1. (A) Diagrammatic representation of fission yeast cen1. The central domain includes the cnt and imr and is flanked by heterochromatic otr. (B) Arrested nda3 Bub3-GFP cells were fixed and labeled with anti-GFP antibodies and with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining of the condensed DNA. Bar, 10 μm. (C) Bub1/3-GFP ChIPs from nda3 cells that had been incubated at 18°C to induce a checkpoint-dependent mitotic arrest. The cnt and imr of cen1 were enriched in the anti-GFP (Bub3 and Bub1) immunoprecipitations from mitotically arrested cells but were barely detectable in cycling cells (32°C). fbp is a noncentromeric, euchromatic negative control.

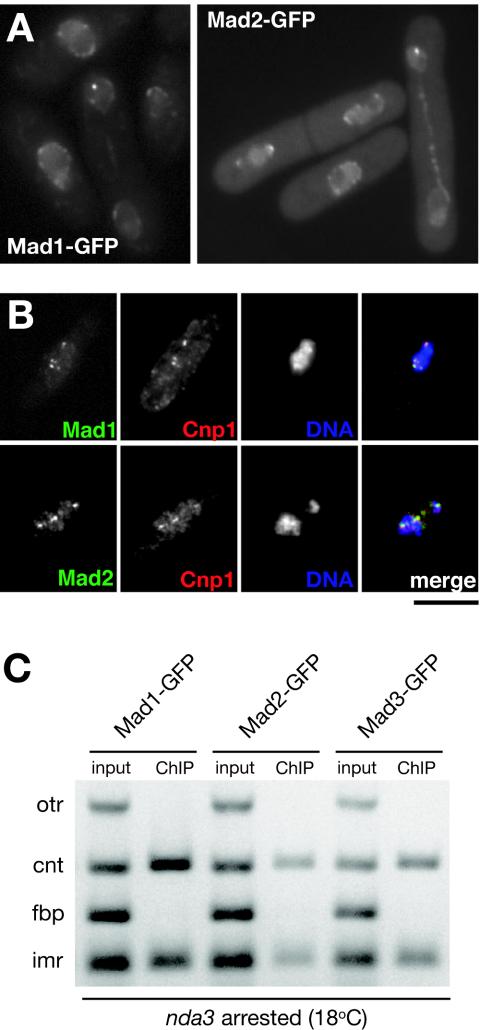

Where are the other fission yeast checkpoint components? It has been reported that Mad1 and Mad2 proteins are at the nuclear periphery, in both budding yeast and vertebrates (10, 30). In agreement with a recent report (29), we found that fission yeast Mad1 and Mad2 localized to the nuclear periphery for most of the cell cycle (Fig. 4A) and, in addition, we found that they were recruited to kinetochores in checkpoint-arrested nda3 cells (Fig. 4B). ChIP experiments revealed that all three Mad proteins associated with the central domain of the centromere and not to the outer heterochromatic repeats (Fig. 4C). Thus, the Mad proteins, Bub1p, and Bub3p all specifically associate with the same region of centromeres upon checkpoint arrest and interact with the central domain upon which the kinetochore is built (49).

FIG. 4.

Mad1/2 proteins localize to kinetochores in checkpoint-arrested cells and interact with the central core of centromeres in mitosis. (A) Images of cycling cells showing that Mad1-GFP and Mad2-GFP localize to the nuclear periphery. (B) nda3-arrested cells containing Mad1-GFP or Mad2-GFP show that these proteins are recruited to kinetochores, where they colocalize with Cnp1. Bar, 4 μm. (C) ChIP from nda3-arrested cells reveals that central domain DNA is enriched in anti-GFP immunoprecipitations for all three Mad proteins.

Bub3p and Bub1p are interdependent for their kinetochore localization.

Two experiments were carried out to test whether other checkpoint proteins are required for Bub3-GFP recruitment to S. pombe kinetochores. In one experiment mutants were synchronized and then imaged as they went through mitosis under conditions that activate the spindle checkpoint. In the second experiment, mad2+ overexpression was used to induce a stable metaphase arrest (23).

Experiment 1.

In experiment 1, wild-type and mutant cells were presynchronized early in S phase with HU and then released into medium containing the microtubule-depolymerizing drug CBZ. This drug activates the spindle checkpoint upon entry into mitosis. Bub3-GFP foci were readily detected in wild-type cells and in mitotic mad1, mad2, and mad3 mutants, leading us to conclude that Bub3p recruitment is independent of the Mad proteins (data not shown). However, Bub3-GFP foci were not detectable in the bub1 and mph1 mutants, suggesting that Bub1p and Mph1p are required for efficient targeting of Bub3p to kinetochores.

Experiment 2.

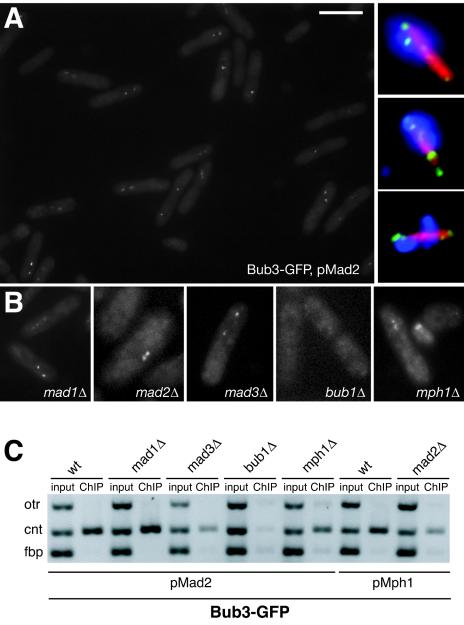

To confirm these results, mad2+ overexpression was used to induce a stable mitotic arrest (apart from the mad2Δ mutant, in which mph1+ was overexpressed [22]). Figure 5A and B show that mad2+ overexpression in wild-type cells resulted in a very good mitotic arrest, with ∼80% of cells having bright Bub3-GFP foci, and that the mad1, mad2, and mad3 mutations did not prevent Bub3-GFP recruitment. As in the first experiment, Bub3-GFP foci were never detected in bub1Δ cells. However, we did detect Bub3-GFP spots when mad2+ was overexpressed in mph1Δ cells, although these were often faint. The Bub3-GFP foci colocalized with Cnp1 (data not shown), confirming that they were at kinetochores. ChIP experiments clearly demonstrated that Bub3-GFP was enriched on central core chromatin in all mutants apart from the bub1Δ strain (Fig. 5C). The very faint PCR products observed for otr and cnt in the bub1Δ ChIP were not above background levels, and the intensity of cnt was never more than that of the euchromatic negative control (fbp). This demonstrated that there is no enrichment of Bub3-GFP at centromeres in the absence of Bub1p.

FIG. 5.

The recruitment of Bub3p to kinetochores is dependent on Bub1p. (A) Live-cell imaging of a field of wild-type Bub3-GFP cells that had been arrested in mitosis by overexpression of Mad2p. Around 80% of cells displayed bright Bub3-GFP foci. (Inset) Images of fixed cells labeled with anti-GFP (green) or antitubulin (red) antibodies and 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). (B) Examples of live-cell images from mutants containing Bub3-GFP and arrested where possible with pREP3X-mad2. pREP41X-mph1 was used to activate the checkpoint in mad2 mutants. The only strain clearly lacking Bub3-GFP foci was bub1Δ, although they were often reduced in intensity in the mph1Δ strain. Bar, 10 μm. (C) ChIPs from these strains clearly demonstrated that central core DNA is enriched in anti-GFP (Bub3) immunoprecipitates in all mutants except bub1Δ.

Note that rather than Mad2p and Mad3p having a direct role to play in Bub3p recruitment, the weaker Bub3 ChIP signal in the mad2 and mad3 mutants is most likely due to the fact that they do not arrest efficiently and have a low mitotic index when mph1+ and mad2+ are overexpressed (22, 42). Indeed, in these strains we observed only ∼25% of cells with bright Bub3-GFP foci.

We conclude that Bub3p recruitment to fission yeast kinetochores is dependent on Bub1p and that it is independent of the three Mad proteins. While there was little evidence of Bub3p recruitment in CBZ-treated mph1Δ cells (data not shown), it was clear that Mph1p is not absolutely required for Bub3p recruitment, as Bub3-GFP foci and good ChIP signals were obtained from the Mad2p-arrested mph1Δ cells.

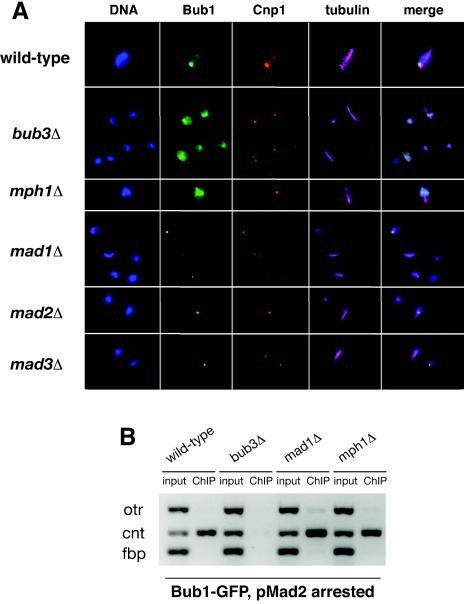

In vertebrates and budding yeast, Bub3 is required for Bub1 recruitment. To investigate this in fission yeast, we analyzed Bub1-GFP in the checkpoint mutants. Figure 6A shows images from cycling cultures. Bub1-GFP was found in the nuclei of all of the checkpoint mutants, but no kinetochore enrichment was observed in mitotic bub3Δ or mph1Δ cells. The same two experiments were then carried out, as described above, to analyze Bub3-GFP targeting in checkpoint mutants. When cells were presynchronized in S phase and released into mitosis, kinetochore signals were observed for Bub1-GFP in the mad mutants but not in bub3Δ or mph1Δ cells (data not shown). Thus, Bub1p recruitment to kinetochores is independent of the three Mad proteins. When mad2+ was overexpressed to induce a mitotic arrest, ChIP experiments did not detect centromere association of Bub1p in bub3Δ cells, but there was clear centromere association of Bub1p in mad1Δ and mph1Δ strains (Fig. 6B). Supporting fluorescent images are shown in Fig. S2 of the supplemental material.

FIG. 6.

Recruitment of Bub1p to kinetochores is dependent on Bub3p. (A) The strains indicated were grown to log phase, fixed, and then analyzed by triple-label immunofluorescence using antitubulin, anti-Cnp1, and anti-GFP (Bub1) antibodies. The mitotic wild-type, mad1Δ, mad2Δ, and mad3Δ cells contain short spindles and Bub1-GFP foci, but the bub3Δ cells and mph1Δ cells have no detectable foci. (B) ChIPs of Bub1-GFP clearly showed that Bub1p was enriched on central core chromatin in wild-type, mad1Δ, and mph1Δ strains, but not in bub3Δ cells overexpressing Mad2p.

To summarize, using four distinct approaches (fixed mitotic cells, CBZ-treated cells, Mad2p-arrested cells, and ChIP), we have found that there is clear interdependence for Bub1p and Bub3p recruitment to the central core of fission yeast centromeres. There is also some dependence on Mph1 kinase function, but this is not absolute, as kinetochore recruitment of both Bub proteins was observed in the mph1Δ strain upon Mad2 overexpression. The Mad proteins are not required for the recruitment of Bub1p and Bub3p to fission yeast kinetochores.

The conserved N-terminal domain of Bub1p is required for its enrichment on kinetochores, for Bub3p and Mad3p targeting, and for spindle checkpoint function.

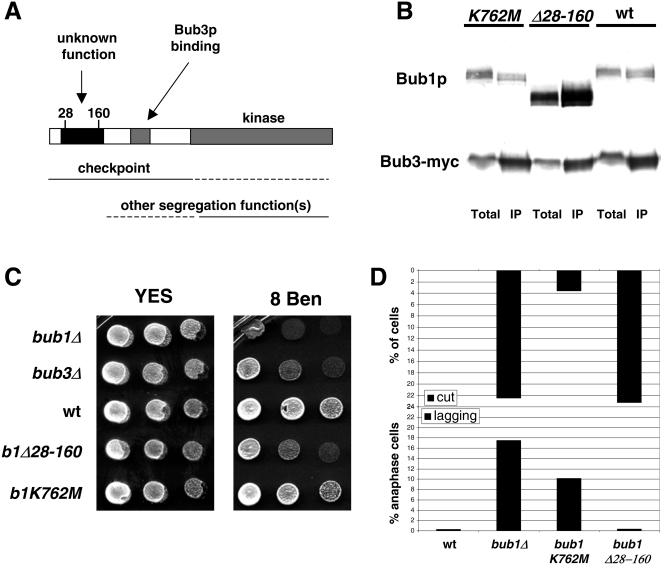

Sequence analysis of Bub1p revealed three conserved domains: a C-terminal kinase domain, the GLEBS domain that is required for Bub3p binding (65), and a domain near the N terminus that has no known function (Fig. 7A). The latter is well conserved and shows striking homology with Mad3p (42). To determine the function of this domain, amino acids 28 to 160 of the Bub1 protein were deleted, producing bub1Δ28-160. This left the GLEBS domain (residues 264 to 289) intact and, as demonstrated by coimmunoprecipitation, Bub3p binding was not affected (Fig. 7B). Figure 7C shows that the bub1Δ28-160 strain was benomyl sensitive, but not as sensitive as the bub1Δ strain. This could suggest that Bub1Δ28-160p has lost a subset of Bub1 functions or that all of its functions are partially defective.

FIG. 7.

The conserved N-terminal domain of Bub1p plays a kinetochore targeting role that is crucial for spindle checkpoint function, but not for Bub3p binding or the prevention of lagging chromosomes. (A) Schematic model of the conserved domains of Bub1p and their likely functions, indicating the position of the deleted region in the N-terminal domain. (B) Bub3-Myc immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted and shown to contain both wild type and mutant Bub1Δ28-160p. No clear effect on this Bub protein interaction was detected. Note that in this anti-Bub1 immunoblot it appears that the Bub1Δ28-160 protein is more abundant than wild-type Bub1p, both in the crude extract (Total) and the anti-Bub3 immunoprecipitate (IP). While this was reproducible, we do not believe it to be the case. In fact, our Bub1 antibody recognized the mutant protein better than wild-type Bub1p (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material). (C) The indicated strains were tested for benomyl sensitivity. Images were taken after growth at 30°C for 4 days. (D) Quantitation of checkpoint and chromosome segregation defects in different bub1 alleles. Quantitation of the Cut phenotype observed in different bub1 nda3 strains after 6 h at 18°C was plotted as a percentage of the total population (see Fig. S2C in the supplemental material for supporting images). Lagging chromosomes were quantitated after fixing cells and staining them with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole and antitubulin antibodies, and results are plotted as the percentage of anaphase cells displaying them (7).

To further characterize the checkpoint role of the N terminus of Bub1p, we crossed bub1Δ28-160 with nda3. nda3 bub1Δ28-160 cells died rapidly at their restrictive temperature with the Cut phenotype, demonstrating that residues 28 to 160 are required to maintain a spindle checkpoint arrest (Fig. 7D; see also Fig. S2B of the supplemental material). Checkpoint defects were quantitated in different bub1 alleles through their production of the Cut phenotype when kinetochore attachment was challenged by the nda3 tubulin mutant. This analysis showed that the bub1Δ28-160 mutant behaved like the null mutant, whereas the kinase-dead allele (K762 M) was far better able to arrest and was less benomyl sensitive (Fig. 7C and D). We conclude that, unlike a kinase-dead bub1 allele, bub1Δ28-160 is completely checkpoint defective.

Does the bub1Δ28-160 mutation have a significant effect on Bub1p targeting to kinetochores? To test this, similar analyses were carried out as above for Bub1-GFP in checkpoint mutants: in the first experiment mitotic cells were enriched by synchronization, and in the second a stable mitotic arrest was induced by Mad2p overexpression. cdc25 cells containing Bub1-GFP (or Bub1Δ28-160-GFP) and Cut12-CFP-labeled spindle poles were arrested in G2 at 36°C and then released into mitosis. Spindle length (the distance between the two Cut12 foci) and the presence of Bub1-GFP foci were scored, as was the fluorescence intensity of the Bub1 foci. In bub1Δ28-160 cells there was a clear reduction in the fraction of mitotic cells containing detectable GFP foci, and these foci were all significantly fainter (Fig. 8A). When Mad2p was overexpressed, to induce a mitotic arrest, Bub1Δ28-160p was found at kinetochores at significantly reduced levels, compared to wild-type Bub1-GFP (Fig. 8B). In most cells diffuse nuclear staining was apparent, and in only ∼20% were faint GFP foci detectable (compared to ∼70% of cells that contained bright foci for the wild-type Bub1-GFP control). In addition, a 70% reduction in the association of Bub1Δ28-160p with centromeric DNA was observed with ChIP, compared to the levels of wild-type Bub1p association (Fig. 8C and D). We had great difficulty in detecting Bub3-GFP at kinetochores in bub1Δ28-160 strains (Fig. 8B), and ∼80% reduction was found in the levels of Bub3p associated with central core chromatin (Fig. 8C and D). An even more pronounced effect was found for Mad3p targeting in bub1Δ28-160 strains: we were completely unable to detect Mad3-GFP foci by microscopy (0% of bub1Δ28-160 cells had Mad3 foci, compared to up to 68% of cells in the wild-type control), and the levels of Mad3p associated with central core chromatin were reduced by over 95% in our ChIP assays.

We conclude that the highly conserved N-terminal domain of Bub1p is required for the efficient targeting of Bub1, Bub3, and Mad3 proteins to fission yeast kinetochores. This is the first clear function for this domain of Bub1p and highlights the importance of efficient kinetochore targeting for Bub1 checkpoint function.

Do fission yeast Bub proteins have other chromosome segregation functions?

Fission yeast bub1Δ mutants have an elevated rate of chromosome loss and a high incidence of lagging chromosomes (6). Analysis of segregation of the Ch16 minichromosome and of GFP-labeled chromosome 2 revealed that bub3Δ and mad3Δ strains had much lower rates of chromosome loss (Table 2). In addition, Table 2 and Fig. 7D show that bub1Δ28-160, bub3Δ, and mad3Δ strains all displayed few, if any, lagging chromosomes. In those mutants, lagging chromosomes were only found in 0 to 3% of anaphase cells, compared to >15% for the bub1Δ strain. Our interpretation of these results is that a checkpoint defect does not lead to the production of lagging chromosomes and that these are observed in bub1Δ due to the lack of another Bub1p function(s). Interestingly, the “kinase-dead” bub1K762 M mutant, which has a robust checkpoint response, does display significantly increased levels of lagging chromosomes (∼10%). We conclude that some of these other Bub1p functions are kinase dependent. Other assays confirmed this: while bub1K762 M did have significant rates of missegregation of chromosome 2, bub1Δ28-160 did not (Table 2).

In summary, we have shown that two bub mutants, one lacking Bub1p, Bub3p, and Mad3p at kinetochores (bub3Δ) and the other with greatly reduced levels of these proteins at kinetochores (bub1Δ28-160), display almost no lagging chromosomes or chromosome loss. We conclude that the other chromosome segregation functions of Bub1p do not require its N-terminal domain, or its enrichment at kinetochores, and that they are Bub3p and Mad3p independent. Finally, we conclude that bub1Δ28-160 acts as a separation-of-function allele: while it lacks checkpoint function, it is still competent for other Bub1p chromosome segregation functions.

DISCUSSION

All spindle checkpoint proteins associate with the central domain of centromeres.

In this fission yeast study, we performed detailed molecular genetic and cytological analyses of the interdependencies of the Mad and Bub spindle checkpoint proteins for their recruitment to kinetochores. We have shown that Bub3p, Mad3p, and Bub1p get recruited to kinetochores early in mitosis in each cell cycle. Fission yeast Bub1 had been shown to interact weakly with centromeric DNA in a prolonged nda3 arrest, by using ChIP (62). Here we demonstrate that Mad1p, Mad2p, Mad3p, Bub1p, and Bub3p all associate with the central domain of centromere 1. This location within the centromere is consistent with their proposed roles in monitoring kinetochore-microtubule interactions, as the central domain is the site of kinetochore assembly. In addition, it puts them all in the same place upon checkpoint activation, which is consistent with models in which the kinetochore acts as a scaffold for the formation of complexes, such as the MCC (Cdc20/Mad2/Mad3/Bub3) anaphase inhibitor (12, 44).

It is noteworthy that the checkpoint proteins do not associate with the heterochromatic outer repeat regions of the centromeres, which recruit a high density of cohesin (8) and are required for full centromere activity. Their failure to interact with outer repeat DNA, and also the lack of an effect of checkpoint mutations in silencing assays (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), shows that the Mad/Bub/Mph1 proteins are unlikely to have a direct role in heterochromatic centromere structure.

We found that all of the Mad and Bub proteins are recruited to kinetochores when Mad2p is overexpressed, even though kinetochores are likely to be attached to spindle microtubules in these cells. This is perhaps surprising, and we cannot rule out the possibility that Mad2p overexpression leads to subtle kinetochore or spindle defects that activate the spindle checkpoint. However, we favor the idea that Mad2p overexpression is simply “trapping” fission yeast cells at a point in the cell cycle at which their kinetochores are competent for Mad/Bub protein recruitment. Work is ongoing to analyze the precise nature of the metaphase arrest in these cells.

Bub3p as a targeting factor?

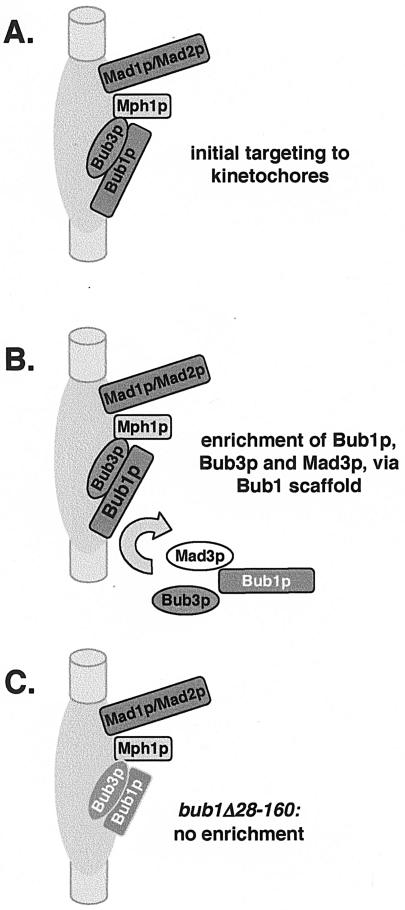

Unlike its mouse homologue, we found that fission yeast Rae1 protein does not play any role in the spindle checkpoint. While the reason for this is unclear, it makes studies of Bub1p/Bub3p targeting simpler to interpret. Bub3p is required for Mad3p recruitment to fission yeast kinetochores (42), and here we demonstrated that it is also required for Bub1p recruitment. These results are consistent with the proposed role of vertebrate Bub3p as a targeting factor for Bub1 and BubR1 (60). However, we also found that Bub3p recruitment was dependent on Bub1p, which argues that Bub3p is not simply a targeting factor, as it itself is dependent on Bub1p. It seems most likely that it is the Bub1p-Bub3p complex that is initially targeted to kinetochores. Once established there, Bub1/3p could then act as a scaffold for the recruitment of additional Bub1p, Bub3p, and Mad3p (Fig. 9), making them readily detectable by microscopy and ChIP techniques.

FIG. 9.

Speculative scaffold model for Bub1p. (A) The Bub1p-Bub3p complex is targeted to kinetochores. Proximity between proteins was used here to reflect dependencies for recruitment. For example, Mad2p requires Mad1p, and Bub3p and Bub1p are interdependent. (B) In wild-type cells, the N terminus of Bub1p then acts as a scaffold for the recruitment of further molecules of Bub3p, Mad3p, and Bub1p. Such a scaffolding role is supported by FRAP studies in vertebrates (26, 54), which have shown that Bub1p is a relatively stable component of outer kinetochores. (C) The Bub1Δ28-160 protein is unable to carry out this scaffolding role, and there is no further enrichment of Bub1p, Bub3p, or Mad3p at kinetochores in this mutant.

Previous work in Xenopus laevis extracts has argued that the Mps1 protein kinase is required for kinetochore targeting of CENP-E, Mad1, and Mad2 (1). We found that Mph1p is not an absolute requirement for Mad or Bub protein recruitment in fission yeast, but we did confirm the importance of this protein kinase for efficient kinetochore targeting of all the checkpoint proteins tested.

Kinetochore targeting and checkpoint signaling.

Our results highlight the importance of the highly conserved residues (28 to 160) at the N terminus of Bub1p for kinetochore targeting of Bub1p, Bub3p, and Mad3p. We have demonstrated that efficient targeting of checkpoint proteins to kinetochores is crucial for spindle checkpoint signaling but that it is not required for all chromosome segregation functions of Bub1p. A requirement for kinetochore targeting of Mad/Bub proteins for checkpoint signaling has been inferred in many other studies, but in those experiments the kinetochore itself was also perturbed, either through laser ablation or kinetochore protein depletion. We believe our work to be the most direct demonstration that kinetochore targeting of spindle checkpoint components is required for a checkpoint arrest.

Vertebrate experiments have argued that the GLEBS domain of Bub1 is sufficient for kinetochore targeting (65), which would be inconsistent with our fission yeast results. However, those vertebrate studies were carried out in cells expressing full-length endogenous Bub1, Bub3, and Rae1 proteins. We suggest that while GLEBS is sufficient for Bub3/Rae1 binding, this complex may still be dependent on the endogenous Bub1 protein (and its N-terminal domain) for efficient kinetochore enrichment.

FRAP has demonstrated that all of the vertebrate spindle checkpoint components display a dynamic association with kinetochores and that their behavior is regulated throughout mitosis (25, 26). Their half-life on kinetochores varies from around 3 to 60 s. Interestingly, Bub1 and Mad1 display a significantly more stable association with kinetochores than the other checkpoint components (26, 54), and it has been proposed that these proteins might form a scaffold to which other checkpoint proteins could be recruited and upon which anaphase inhibitors could be assembled (44). We believe that our fission yeast data are consistent with this view. One explanation of the bub1Δ28-160 mutant phenotype is that this mutant protein does not act as a good scaffold on kinetochores, and that is why dramatically reduced levels of Bub3p and Mad3p are recruited (Fig. 9) and checkpoint signaling is disrupted. Our imaging and ChIP experiments showed reduced steady-state levels of the Bub and Mad3 proteins at kinetochores in the bub1Δ28-160 mutant. This could be due to inefficient targeting of these proteins to kinetochores or to a reduction in their residence time (inefficient maintenance) at kinetochores. We are currently unable to distinguish between these explanations and must now analyze the dynamics of wild-type and mutant fission yeast Mad/Bub proteins at kinetochores by using imaging techniques such as FRAP.

Bub1 kinase activity and the checkpoint.

While the N-terminal domain of Bub1p is crucial for its checkpoint function, our analysis suggested that Bub1 kinase activity is less important. This view agrees with budding yeast and Xenopus data (11, 55, 66), and it has recently been reported that fission yeast bub1-K762R, and even a kinase deletion, are partially competent for mitotic checkpoint function (69). We have made similar C-terminal truncations, removing the kinase domain and more of Bub1p, and found that some of these maintained robust spindle checkpoint function (unpublished data). It is clear that kinase activity is not required for the localization of Bub1p to kinetochores (unpublished data and reference 69), nor for its ability to recruit Bub3p and Mad3p (55). However, kinase activity is very important for the meiotic functions of Bub1p (63, 69) and for other, noncheckpoint mitotic functions (see below).

Bub1p, but not Bub3p, has other segregation functions.

Bub1p has been demonstrated to have key roles in fission yeast meiosis, both in ensuring mono-orientation of sister kinetochores in meiosis I and in the protection of Rec8-mediated centromere cohesion (7). It has recently been reported that Sgo1 and Sgo2 localization to kinetochores is Bub1 dependent (35). Sgo1 acts as a protector of Rec8 meiotic cohesin, and Sgo2 is required to ensure mono-orientation of sisters in meiosis I (35, 52). Thus, a major meiotic role of Bub1p could be to localize these proteins.

Are the Sgo proteins important mitotic targets for Bub1 activity? Sgo1 is not expressed in mitosis, and at present the mitotic role(s) of Sgo2 is far from clear, as there is no detectable mitotic cohesion defect in sgo2Δ cells (35). The localization of Sgo2 to kinetochores in mitosis was shown to be Bub1 dependent (35). However, we have been unable to detect any lagging chromosomes in sgo2 cells (data not shown). Thus, an inability to localize Sgo2 in mitosis cannot explain the lagging chromosomes observed in the bub1Δ strain, and other Bub1 targets must exist.

What might these Bub1 segregation functions be? It is thought that lagging chromosomes are due to merotelic attachment, where the kinetochore of a single sister chromatid is attached to microtubules from both spindle poles and it is being pulled in both directions on the anaphase spindle. Mutations affecting the outer repeats or the central core of fission yeast centromeres show a high incidence of lagging chromosomes, and they also alleviate silencing of reporter genes within the heterochromatin (3, 50). However, as we found no detectable alleviation of silencing at either the central core or outer repeat regions of centromeres in bub1, mad2, or mph1 mutants (data not shown; see Fig. S3A in the supplemental material), we don't think that a heterochromatin defect can explain the production of lagging chromosomes in bub1 mutants. Certain kinetochore mutants lead to a reduced association of Cnp1 with the central core of centromeres (50, 58). We carried out ChIP analysis of the levels of Cnp1 associated with cen1 in various checkpoint mutants, including bub1Δ, but observed no clear evidence of reduced levels (see Fig. S3B in the supplemental material). We have not detected clear effects on mitotic cohesion in the bub1Δ strain (unpublished data; P. Bernard, personal communication), although subtle defects remain a possibility. We deduce that lack of Bub1p has no clear structural consequence on chromatin structure at fission yeast centromeres.

Our analysis suggests that while the kinase activity of Bub1p is important for the prevention of lagging chromosomes, its kinetochore enrichment is not, as neither bub1Δ28-160 nor bub3Δ display lagging chromosomes. We cannot rule out that an undetectable level of Bub1p gets to kinetochores in the bub3Δ mutant, but we note that the Caenorhabditis elegans homologue of Bub1p has also been localized to a matrix-like structure in metaphase that does not coalign with spindle microtubules (46). Such a matrix might exist in other organisms, including fission yeast, and this could be where the kinase activity of Bub1p carries out its segregation function(s). Alternatively, soluble nucleoplasmic Bub1 kinase activity could modify and thereby target or regulate proteins with segregation roles. Much remains unclear about the chromosome segregation functions of Bub1p, and the identification of its kinase substrates will be an important step towards understanding these mitotic roles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We particularly thank David Millband for yeast strains and preliminary data and Sheila Kadura and Shelley Sazer for communicating results prior to publication. We are indebted to Robin Allshire and Alison Pidoux for their generous supply of reagents and advice relating to the ChIP protocol and silencing assays. In addition, we thank Shelley Sazer for pREP3X-mad2 and pREP41X-mph1; Ravi Dhar for rae1-167 and Rae1p reagents; Keith Gull, Iain Hagan, and Barbara Mellone for antibodies; Yasushi Hiraoka, Tomohiro Matsumoto, Jonathan Miller, Paul Nurse, and Shelley Sazer for yeast strains; all members of the Hardwick lab for their support and discussions; and Alison Pidoux for critical reading of the manuscript.

Work in the Hordwick lab is supported by the Wellcome Trust, of which K.G.H. is a Senior Research Fellow; J.P.J. is supported by the CNRS, the University of Bordeaux 2, and l’Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrieu, A., L. Magnaghi-Jaulin, J. A. Kahana, M. Peter, A. Castro, S. Vigneron, T. Lorca, D. W. Cleveland, and J. C. Labbe. 2001. Mps1 is a kinetochore-associated kinase essential for the vertebrate mitotic checkpoint. Cell 106:83-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfa, C., P. Fantes, J. Hyams, M. McLeod, and E. Warbrick. 1993. Experiments with fission yeast. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 3.Allshire, R. C., E. R. Nimmo, K. Ekwall, J. P. Javerzat, and G. Cranston. 1995. Mutations derepressing silent centromeric domains in fission yeast disrupt chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 9:218-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babu, J. R., K. B. Jeganathan, D. J. Baker, X. Wu, N. Kang-Decker, and J. M. van Deursen. 2003. Rae1 is an essential mitotic checkpoint regulator that cooperates with Bub3 to prevent chromosome missegregation. J. Cell Biol. 160:341-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahler, J., J. Q. Wu, M. S. Longtime, N. G. Shah, A. McKenzie III, A. B. Steever, A. Wach, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targetting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 14:943-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernard, P., K. Hardwick, and J. P. Javerzat. 1998. Fission yeast bub1 is a mitotic centromere protein essential for the spindle checkpoint and the preservation of correct ploidy through mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 143:1775-1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernard, P., J. F. Maure, and J. P. Javerzat. 2001. Fission yeast Bub1 is essential in setting up the meiotic pattern of chromosome segregation. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:522-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernard, P., J. F. Maure, J. F. Partridge, S. Genier, J. P. Javerzat, and R. C. Allshire. 2001. Requirement of heterochromatin for cohesion at centromeres. Science 294:2539-2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brady, D. M., and K. G. Hardwick. 2000. Complex formation between Mad1p, Bub1p and Bub3p is crucial for spindle checkpoint function. Curr. Biol. 10:675-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell, M. S., G. K. Chan, and T. J. Yen. 2001. Mitotic checkpoint proteins HsMAD1 and HsMAD2 are associated with nuclear pore complexes in interphase. J. Cell Sci. 114:953-963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, R. H. 2004. Phosphorylation and activation of Bub1 on unattached chromosomes facilitate the spindle checkpoint. EMBO J. 23:3113-3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleveland, D. W., Y. Mao, and K. F. Sullivan. 2003. Centromeres and kinetochores. From epigenetics to mitotic checkpoint signaling. Cell 112:407-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding, R., K. L. McDonald, and J. R. McIntosh. 1993. Three-dimensional reconstruction and analysis of mitotic spindles from the yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Cell Biol. 120:141-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang, G., H. Yu, and M. W. Kirschner. 1998. The checkpoint protein MAD2 and the mitotic regulator CDC20 form a ternary complex with the anaphase-promoting complex to control anaphase initiation. Genes Dev. 12:1871-1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraschini, R., A. Beretta, G. Lucchini, and S. Piatti. 2001. Role of the kinetochore protein Ndc10 in mitotic checkpoint activation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266:115-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fraschini, R., A. Beretta, L. Sironi, A. Musacchio, G. Lucchini, and S. Piatti. 2001. Bub3 interaction with Mad2, Mad3 and Cdc20 is mediated by WD40 repeats and does not require intact kinetochores. EMBO J. 20:6648-6659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardner, R. D., A. Poddar, C. Yellman, P. A. Tavormina, M. C. Monteagudo, and D. J. Burke. 2001. The spindle checkpoint of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires kinetochore function and maps to the CBF3 domain. Genetics 157:1493-1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillett, E. S., C. W. Espelin, and P. K. Sorger. 2004. Spindle checkpoint proteins and chromosome-microtubule attachment in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 164:535-546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardwick, K. G., R. J. Johnston, D. Smith, and A. W. M. Murray. 2000. MAD3 encodes a novel component of the spindle checkpoint which interacts with Bub3p, Cdc20p and Mad2p. J. Cell Biol. 148:871-882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardwick, K. G., and A. W. Murray. 1995. Mad1p, a phosphoprotein component of the spindle assembly checkpoint in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 131:709-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartwell, L. H., and T. A. Weinert. 1989. Checkpoints: controls that ensure the order of cell cycle events. Science 246:629-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He, X., M. H. Jones, M. Winey, and S. Sazer. 1998. Mph1, a member of the Mps1-like family of dual specificity protein kinases, is required for the spindle checkpoint in S. pombe. J. Cell Sci. 111:1635-1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He, X. W., T. E. Patterson, and S. Sazer. 1997. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe spindle checkpoint protein mad2p blocks anaphase and genetically interacts with the anaphase-promoting complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:7965-7970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiraoka, Y., T. Toda, and M. Yanagida. 1984. The NDA3 gene of fission yeast encodes beta-tubulin: a cold-sensitive nda3 mutation reversibly blocks spindle formation and chromosome movement in mitosis. Cell 39:349-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howell, B. J., D. B. Hoffman, G. Fang, A. W. Murray, and E. D. Salmon. 2000. Visualization of Mad2 dynamics at kinetochores, along spindle fibers, and at spindle poles in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 150:1233-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howell, B. J., B. Moree, E. M. Farrar, S. Stewart, G. Fang, and E. D. Salmon. 2004. Spindle checkpoint protein dynamics at kinetochores in living cells. Curr. Biol. 14:953-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoyt, M. A., L. Totis, and B. T. Roberts. 1991. S. cerevisiae genes required for cell cycle arrest in response to loss of microtubule function. Cell 66:507-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hwang, L. H., L. F. Lau, D. L. Smith, C. A. Mistrot, K. G. Hardwick, E. S. Hwang, A. Amon, and A. W. Murray. 1998. Budding yeast Cdc20: a target of the spindle checkpoint. Science 279:1041-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ikui, A. E., K. Furuya, M. Yanagida, and T. Matsumoto. 2002. Control of localization of a spindle checkpoint protein, Mad2, in fission yeast. J. Cell Sci. 115:1603-1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iouk, T., O. Kerscher, R. J. Scott, M. A. Basrai, and R. W. Wozniak. 2002. The yeast nuclear pore complex functionally interacts with components of the spindle assembly checkpoint. J. Cell Biol. 159:807-819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janke, C., J. Ortiz, J. Lechner, A. Shevchenko, M. M. Magiera, C. Schramm, and E. Schiebel. 2001. The budding yeast proteins Spc24p and Spc25p interact with Ndc80p and Nuf2p at the kinetochore and are important for kinetochore clustering and checkpoint control. EMBO J. 20:777-791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson, V. L., M. I. F. Scott, S. V. Holt, D. Hussein, and S. S. Taylor. 2004. Bub1 is required for kinetochore localization of BubRI, Cenp-E, Cenp-F and Mad2, and chromosome congression. J. Cell Sci. 117:1577-1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karpen, G. H., and R. C. Allshire. 1997. The case for epigenetic effects on centromere identity and function. Trends Genet. 13:489-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim, S. H., D. P. Lin, S. Matsumoto, A. Kitazono, and T. Matsumoto. 1998. Fission yeast Slp1: an effector of the Mad2-dependent spindle checkpoint. Science 279:1045-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kitajima, T. S., S. A. Kawashima, and Y. Watanabe. 2004. The conserved kinetochore protein shugoshin protects centromeric cohesion during meiosis. Nature 427:510-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li, R., and A. W. Murray. 1991. Feedback control of mitosis in budding yeast. Cell 66:519-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li, X., and R. B. Nicklas. 1995. Mitotic forces control a cell-cycle checkpoint. Nature 373:630-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo, X., Z. Tang, J. Rizo, and H. Yu. 2002. The mad2 spindle checkpoint protein undergoes similar major conformational changes upon binding to either mad1 or cdc20. Mol. Cell 9:59-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin-Lluesma, S., V. M. Stucke, and E. A. Nigg. 2002. Role of Hec1 in spindle checkpoint signaling and kinetochore recruitment of Mad1/Mad2. Science 297:2267-2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCleland, M. L., R. D. Gardner, M. J. Kallio, J. R. Daum, G. J. Gorbsky, D. J. Burke, and P. T. Stukenberg. 2003. The highly conserved Ndc80 complex is required for kinetochore assembly, chromosome congression, and spindle checkpoint activity. Genes Dev. 17:101-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Millband, D. N., L. Campbell, and K. G. Hardwick. 2002. The awesome power of multiple model systems: interpreting the complex nature of spindle checkpoint signalling. Trends Cell Biol. 12:205-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Millband, D. N., and K. G. Hardwick. 2002. Fission yeast Mad3p is required for Mad2p to inhibit the anaphase-promoting complex and localizes to kinetochores in a Bub1p-, Bub3p-, and Mph1p-dependent manner. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:2728-2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moreno, S., A. Klar, and P. Nurse. 1991. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 194:795-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Musacchio, A., and K. G. Hardwick. 2002. The spindle checkpoint: structural insights into dynamic signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3:731-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nabeshima, K., T. Nakagawa, A. F. Straight, A. Murray, Y. Chikashige, Y. M. Yamashita, Y. Hiraoka, and M. Yanagida. 1998. Dynamics of centromeres during metaphase-anaphase transition in fission yeast: Dis1 is implicated in force balance in metaphase bipolar spindle. Mol. Biol. Cell 9:3211-3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oegema, K., A. Desai, S. Rybina, M. Kirkham, and A. A. Hyman. 2001. Functional analysis of kinetochore assembly in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Biol. 153:1209-1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Partridge, J. F., B. Borgstrom, and R. C. Allshire. 2000. Distinct protein interaction domains and protein spreading in a complex centromere. Genes Dev. 14:783-791. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peters, J. M. 2002. The anaphase-promoting complex: proteolysis in mitosis and beyond. Mol. Cell 9:931-943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pidoux, A. L., and R. C. Allshire. 2000. Centromeres: getting a grip of chromosomes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12:308-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pidoux, A. L., W. Richardson, and R. C. Allshire. 2003. Sim4: a novel fission yeast kinetochore protein required for centromeric silencing and chromosome segregation. J. Cell Biol. 161:295-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poddar, A., J. A. Daniel, J. R. Daum, and D. J. Burke. 2004. Differential kinetochore requirements for establishment and maintenance of the spindle checkpoint are dependent on the mechanism of checkpoint activation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Cycle 3:197-204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rabitsch, K. P., J. Gregan, A. Schleiffer, J. P. Javerzat, F. Eisenhaber, and K. Nasmyth. 2004. Two fission yeast homologs of Drosophila Mei-S332 are required for chromosome segregation during meiosis I and II. Curr. Biol. 14:287-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rieder, C. L., R. W. Cole, A. Khodjakov, and G. Sluder. 1995. The checkpoint delaying anaphase in response to chromosome monoorientation is mediated by an inhibitory signal produced by unattached kinetochores. J. Cell Biol. 130:941-948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shah, J. V., E. Botvinick, Z. Bonday, F. Furnari, M. Berns, and D. W. Cleveland. 2004. Dynamics of centromere and kinetochore proteins; implications for checkpoint signaling and silencing. Curr. Biol. 14:942-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharp-Baker, H., and R. H. Chen. 2001. Spindle checkpoint protein Bub1 is required for kinetochore localization of Mad1, Mad2, Bub3, and CENP-E, independently of its kinase activity. J. Cell Biol. 153:1239-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sironi, L., M. Mapelli, S. Knapp, A. De Antoni, K. T. Jeang, and A. Musacchio. 2002. Crystal structure of the tetrameric Mad1-Mad2 core complex: implications of a “safety belt” binding mechanism for the spindle checkpoint. EMBO J. 21:2496-2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sudakin, V., G. K. T. Chan, and T. J. Yen. 2001. Checkpoint inhibition of the APC/C in HeLa cells is mediated by a complex of BubR1, Bub3, Cdc20, Mad2. J. Cell Biol. 154:925-936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takahashi, K., E. S. Chen, and M. Yanagida. 2000. Requirement of Mis6 centromere connector for localizing a CENP-A-like protein in fission yeast. Science 288:2215-2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tang, Z., R. Bharadwaj, B. Li, and H. Yu. 2001. Mad2-independent inhibition of APCCdc20 by the mitotic checkpoint protein BubR1. Dev. Cell 1:227-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taylor, S. S., E. Ha, and F. McKeon. 1998. The human homologue of Bub3 is required for kinetochore localization of Bub1 and a Mad3/Bub1-related protein kinase. J. Cell Biol. 142:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tournier, S., Y. Gachet, V. Buck, J. S. Hyams, and J. B. Millar. 2004. Disruption of astral microtubule contact with the cell cortex activates a Bub1, Bub3, and Mad3-dependent checkpoint in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:3345-3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Toyoda, Y., K. Furuya, G. Goshima, K. Nagao, K. Takahashi, and M. Yanagida. 2002. Requirement of chromatid cohesion proteins Rad21/Scc1 and Mis4/Scc2 for normal spindle-kinetochore interaction in fission yeast. Curr. Biol. 12:347-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tunquist, B. J., M. S. Schwab, L. G. Chen, and J. L. Maller. 2002. The spindle checkpoint kinase bub1 and cyclin e/cdk2 both contribute to the establishment of meiotic metaphase arrest by cytostatic factor. Curr. Biol. 12:1027-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vanoosthuyse, V., and K. G. Hardwick. 2003. The complexity of Bub1 regulation—phosphorylation, phosphorylation, phosphorylation. Cell Cycle 2:118-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang, X., J. R. Babu, J. M. Harden, S. A. Jablonski, M. H. Gazi, W. L. Lingle, P. C. de Groen, T. J. Yen, and J. M. A. van Deursen. 2001. The mitotic checkpoint protein hBUB3 and the mRNA export factor hRAE1 interact with GLEBS-containing proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 276:26559-26567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Warren, C. D., D. M. Brady, R. C. Johnston, J. S. Hanna, K. G. Hardwick, and F. A. Spencer. 2002. Distinct chromosome segregation roles for spindle checkpoint proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:3029-3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weiss, E., and M. Winey. 1996. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae spindle pole body duplication gene MPS1 is part of a mitotic checkpoint. J. Cell Biol. 132:111-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wigge, P. A., and J. V. Kilmartin. 2001. The Ndc80p complex from Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains conserved centromere components and has a function in chromosome segregation. J. Cell Biol. 152:349-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yamaguchi, S., A. Decottignies, and P. Nurse. 2003. Function of Cdc2p-dependent Bub1p phosphorylation and Bub1p kinase activity in the mitotic and meiotic spindle checkpoint. EMBO J. 22:1075-1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yamamoto, A., and Y. Hiraoka. 2003. Monopolar spindle attachment of sister chromatids is ensured by two distinct mechanisms at the first meiotic division in fission yeast. EMBO J. 22:2284-2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yoon, J. H., D. C. Love, A. Guhathakurta, J. A. Hanover, and R. Dhar. 2000. Mex67p of Schizosaccharomyces pombe interacts with Rae1p in mediating mRNA export. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8767-8782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.