Abstract

A number of transcription factors that increase the catalytic rate of mRNA synthesis by RNA polymerase II (Pol II) have been purified from higher eukaryotes. Among these are the ELL family, DSIF, and the heterotrimeric elongin complex. Elongin A, the largest subunit of the elongin complex, is the transcriptionally active subunit, while the smaller elongin B and C subunits appear to act as regulatory subunits. While much is known about the in vitro properties of elongin A and other members of this class of elongation factors, the physiological role(s) of these proteins remain largely unclear. To elucidate in vivo functions of elongin A, we have characterized its Drosophila homologue (dEloA). dEloA associates with transcriptionally active puff sites within Drosophila polytene chromosomes and exhibits many of the expected biochemical and cytological properties consistent with a Pol II-associated elongation factor. RNA interference-mediated depletion of dEloA demonstrated that elongin A is an essential factor that is required for proper metamorphosis. Consistent with this observation, dEloA expression peaks during the larval stages of development, suggesting that this factor may be important for proper regulation of developmental events during these stages. The discovery of the role of elongin A in an in vivo model system defines the novel contribution played by RNA polymerase II elongation machinery in regulation of gene expression that is required for proper development.

The mechanism of eukaryotic mRNA synthesis is complex. During its trek down DNA templates, RNA polymerase II (Pol II) encounters many obstacles. To overcome these obstacles, Pol II requires a variety of proteins known as transcription elongation factors. Biochemically distinct from the basal transcription machinery, these proteins have the ability to increase the kinetic rate of mRNA chain elongation by the multiprotein Pol II complex (24, 28-32, 34, 35, 38). One class of elongation factors, which functions by increasing the overall Km and/or the Vmax of elongating polymerase by decreasing the duration and/or frequency of transient pausing as Pol II progresses along DNA templates, includes the ELL family (ELL, ELL2, ELL3, and dELL) and the elongin proteins (2-4, 14, 25, 36, 37, 44).

Elongin was originally purified from rat liver nuclear extracts based on its ability to increase the catalytic rate of transcription by Pol II in an in vitro assay (4). Elongin is a heterotrimeric protein complex comprised of a ∼110-kDa subunit (elongin A), an ∼18-kDa subunit (elongin B), and a ∼15-kDa subunit (elongin C) (2, 4, 12, 13). Elongin A is the transcriptionally active component of this complex, since addition of this protein alone to in vitro transcription assays is capable of stimulating elongation activity. The B and C subunits of the complex function as positive regulators and are unable to stimulate elongation in the absence of the A subunit (1, 4). To date, four elongin A family members have been identified, including a single elongin A homologue in Caenorhabditis elegans and the closely related elongins A2 and A3 in mammals (3, 4, 44). Each of these is able to interact with the elongin BC complex via a small sequence motif known as the BC box. Interestingly, the A2 and A3 homologues share the highest level of sequence homology, and structure-function analyses of fusion proteins containing elongin A3 and elongin A have revealed that the C-terminal domain of elongin A confers dependence on the BC complex for maximal transcription activity (44).

The conserved BC box motif is not exclusive to elongin A family members. This motif is also found in a large number of BC box proteins that are linked through elongins B and C to a protein module composed of a cullin family protein (Cul2 or Cul5) and the ring finger protein, Rbx1, to form elongin BC-based ubiquitin ligase complexes (13, 18, 19). Among the BC box proteins is the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein, which functions as the substrate recognition subunit of an E3 ligase that targets the α subunits of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors (1, 5, 7, 17, 20, 27).

In an effort to gain insight into the functional role(s) of elongin A in vivo, we have identified and characterized the unique Drosophila homologue of the elongin A family (dElongin A or dEloA). Appropriately, dEloA exhibits several in vitro and in vivo properties expected of a Pol II elongation factor. It is able to enhance Pol II elongation in an in vitro transcription assay, and it interacts with phosphorylated Pol II in Drosophila extracts. Further, dEloA colocalizes with Pol II at sites of active transcription on polytene chromosomes. These data support the hypothesis that elongin A is a Pol II elongation factor in vivo.

Developmental expression analysis reveals that dEloA mRNA has a broad pattern of expression, with its peak around early larval stage and continuing during early pupation. The protein levels for dEloA appear to also peak during the larval stages of development, indicating an important role for dEloA during the larval stage and early pupation. Interestingly, animals expressing reduced levels of dEloA due to RNA interference (RNAi) knockdown are unable to make the transition from the larval stages to adulthood and die as pupae, suggesting that dEloA is an essential factor that is required for proper metamorphosis. Our studies demonstrate the following: (i) an in vivo role for elongin A during transcriptional elongation; (ii) that not all elongation factors are created equal, i.e., they are not redundant, and each may have tissue/gene-specific roles during development; (iii) that the elongation factor elongin A is found on transcriptionally active developmental puff sites; and (iv) that elongin A is required for coordinated regulation of gene expression and development. The discovery of the role of elongin A as an RNA polymerase II elongation factor in vivo extends the important contribution played by Pol II elongation machinery in regulation of gene expression that is required for proper development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

The published mammalian elongin A sequence was used to query the National Center for Biotechnology Information database to identify the dEloA homologue (accession number NM_170061, CG6755). Oligonucleotides were designed to PCR amplify the open reading frame from a Drosophila cDNA library. This cDNA was then ligated to the XhoI-EcoRI fragment of the recombinant expression vector, pRSETa (Invitrogen), in frame with an N-terminal His6 and Xpress epitope tag.

For the purpose of performing RNA interference in vivo, a 593-bp fragment of dEloA (bp 400 to 993) was amplified by PCR from the pRSETa-dEloA construct using a 5′ primer containing a nested BglII restriction site and a 3′ primer containing a nested EcoRI restriction site. This product was then ligated to the BglII-EcoRI fragment of pSym-pUASTW (15), which was subsequently used for P-element-mediated transformation in Drosophila embryos.

To generate radiolabeled RNA from the dEloA cDNA for the developmental Northern analysis of dEloA expression, the SalI-EcoRI fragment was excised from the pRSETa construct, containing the 3′ 930 bp of the dEloA cDNA sequence, with an EcoRI-restricted end at its 3′ end and a SalI end at its 5′ end. This fragment was then ligated to the SalI-EcoRI fragment of pGEM-3 (Promega), where it was placed under a T7 promoter at its 3′ end. This was then used to transcribe antisense RNA in the reaction described below.

Northern blot analysis.

Five micrograms of total RNA isolated from Drosophila melanogaster at each of the 10 developmental stages (gift of Dale Dorsett) was denatured in morpholinepropanesulfonic acid-formaldehyde-formamide solution and separated by electrophoresis on a 1% formaldehyde gel at low voltage. Resolved RNAs were transferred to a Biotrans membrane (ICN) and cross-linked to the membrane by UV irradiation. The membrane was incubated in hybridization solution (50% formamide, 10% PEG 8000, 3.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 150 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 250 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2× Denhardt's) for at least 1 h at 65°C before the addition of radiolabeled probe. The antisense RNA probe was prepared by using the pGEM vector containing dEloA cDNA under the control of the T7 promoter at the 3′ end. Antisense RNA transcription was performed using T7 RNA polymerase (Promega) under the following reaction conditions: 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 10 mM NaCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM spermidine, 0.05% Tween 20, 0.5 mM (each) ATP, GTP, and UTP, 0.5 μCi of [32P]CTP (ICN), 0.1 U of RNasin (Promega), and 2 μg of template DNA. Reactions were carried out at 37°C for 60 min and then treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega) for 15 min to remove plasmid template. Antisense RNA was then purified using the RNeasy RNA purification kit (QIAGEN), added to the hybridization mixture, and incubated overnight at 65°C. The blot was then washed successively in buffers containing decreasing concentrations of SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and SDS until background radiation levels reached a minimum. Transcripts were visualized by autoradiography. To visualize the loading control, pGEM containing Drosophila rp49 cDNA (a gift of Dale Dorsett) under T7 was used to generate the antisense RNA radiolabeled probe.

Expression and purification of recombinant dEloA.

dEloA in pRSETa was used to transform BL21(DE3)/pLysE Escherichia coli. Positive transformants were selected by double selection with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml) and were then used to produce overnight cultures in liquid broth containing each antibiotic. Cultures were diluted 1:50, allowed to grow to an optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.4, and then induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (Roche) at 0.5 to 1 mM concentrations for ∼4 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and lysed by repeated freeze-thaw cycles in 1× phosphate-buffered saline. Inclusion bodies were separated from soluble proteins by ultracentrifugation and then homogenized in buffer A (6 M guanidine-HCl, 40 mM Tris) to solubilize the recombinant protein. Homogenates were then ultracentrifuged again to separate soluble protein from cell debris. His-tagged recombinant protein was purified by using Probond nickel-chelating resin (Invitrogen). Briefly, proteins were bound to resin in buffer A. Resin-protein conjugates were washed with buffer B (buffer A plus 40 mM imidazole) three times to remove nonspecifically bound contaminants. Protein was eluted from resin with buffer C (buffer A plus 300 mM imidazole) and vortexing. This was followed by centrifugation to separate the resin from the supernatant containing the eluted protein. Load, flow-through, wash, and bound fractions were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-Express and anti-His6 antibodies (Invitrogen) to examine the efficiency of purification. Using this same strategy, ∼5 mg of recombinant protein was expressed and purified (the purity and identity of the expressed dEloA were determined by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight [MALDI-TOF] mass spectroscopy analysis) for the purpose of raising polyclonal antisera. Protein samples were sent to Research Genetics (Invitrogen, Huntsville, Ala.) for antibody production. For use in the in vitro transcription assay, purified recombinant dEloA was renatured by dialysis in buffer containing 250 mM KCl.

In vitro transcription elongation assay.

Vector containing an adenovirus major late promoter was cut with EcoRI and NdeI. The linear fragment was purified by gel electrophoresis and used in in vitro transcription assays. Preinitiation complexes were assembled at the adenovirus major late promoter with recombinant TBP, TFIIB, TFIIE, TFIIF, and purified rat TFIIH and RNA polymerase II as described previously (37). Transcription was initiated by the addition of 50 μM ATP, 50 μM GTP, 2 μM UTP, 10 μCi of [α-32P]CTP (ICN) (specific activity, 3,000 Ci/mmol) and 7 mM MgCl2. After 10 min at 28°C, 100 μM nonradioactive CTP was added to the reaction mixture, and short transcripts were chased in the presence or absence of purified and renatured recombinant dEloA for the times indicated. Transcripts were analyzed by electrophoresis through a 6% acrylamide-7 M urea-0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA gel and developed using a Molecular Dynamics (Sunnyvale, Calif.) PhosphorImager. Mock-purified and renatured protein was used in the absence of dEloA as a control for the experiment.

Immunofluorescence staining.

Salivary glands were dissected in gland buffer (8), fixed for 30 s in 2% formaldehyde in gland buffer, then in 45% acetic acid, 12% formaldehyde for 3 min, before storage in 67% glycerol-33% phosphate-buffered saline at −20°C. For optimal staining, dEloA polyclonal antibody (dilution, 1:300) was incubated with polytene chromosomes overnight at 4°C. Pol II antibodies (H5 and H14; Covance) were used at a 1:1,000 dilution and with overnight incubation. Appropriate secondary antibodies (Jackson Laboratory) were used at 1:1,000 dilution. Fluorescence detection was carried out with epifluorescence, using an Olympus BX60 fluorescence microscope with an NB barrier filter for fluorescein and Cy2 detection and a WG barrier filter for rhodamine and Cy3. Images were recorded with a SPOT charge-coupled device camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Inc.) using PAX-it imaging software (Midwest Information Systems, Inc.).

Coimmunoprecipitation of phospho-Pol II with dEloA.

Wild-type (OregonR) Drosophila third-instar larvae were homogenized in ice-cold NUN buffer (1 M urea, 300 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES [pH 7.9]) (23). Extract was cleared by centrifugation and halved and incubated with dEloA antibody or preimmune serum at 4°C overnight with gentle agitation. Extract-antibody mixtures were then incubated with protein A Sepharose 4B fast flow resin, preincubated in NUN buffer plus 0.1% bovine serum albumin (pentax fraction V) and 0.1% NP-40 for 3 h at 4°C with gentle agitation. Resin-protein conjugates were washed three to four times with NUN buffer plus bovine serum albumin and NP-40, and bound proteins were released by boiling the resin in Laemmli buffer. Load, flow-through, wash, and bound fractions from each sample set (dEloA polyclonal or preimmune serum) were analyzed by Western blotting for the presence of Ser5-phospho-Pol II using H14 monoclonal antibody (Covance). Protein was visualized using the Western Lightning ECL kit (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences).

Germ line transformation and fly culture.

yw67C23 embryos were injected with the pSympUASTW-dEloA 400-993 construct, together with the helper plasmid pvhsΔ2-3 “Turbo” (33) (kindly provided by Dale Dorsett, St. Louis University School of Medicine) essentially as described previously (40). G0 survivors were crossed to yw67C23 flies, and F1 adults were screened for the presence of w+. At least three independent transgenic lines were used for crosses with Gal4 lines (yw; daughterless Gal4 yw; actin5C Gal4/CyO y+) to activate RNAi.

RESULTS

Identification of a unique elongin A homologue in Drosophila.

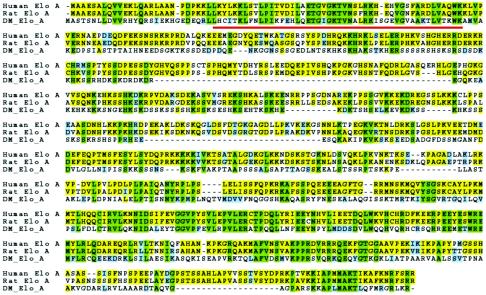

Using the National Center for Biotechnology Information database, we identified the full-length dEloA cDNA based on its primary sequence homology with mammalian elongin A. Although there are three elongin A family members in mammalian cells, there is only one elongin A-like protein in Drosophila. While dEloA is smaller than its mammalian homologues, extensive sequence conservation is found throughout the length of these proteins, with the most highly conserved regions falling within the C-terminal domain required for stimulation of elongation by mammalian elongin A (3) and within the SII (TFIIS)-like N terminus (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Identification of an elongin A homologue in Drosophila. Protein sequence alignment of human, rat, and Drosophila elongin A is shown. Residues identical in all three species are highlighted in green; residues identical in human and rat are highlighted in yellow; residues that are conserved but not identical are highlighted in blue. Drosophila elongin A and mammalian elongin A share 27% identity and 41% similarity. Human and rat elongin A share 82% identity. The red line indicates the SII homology region.

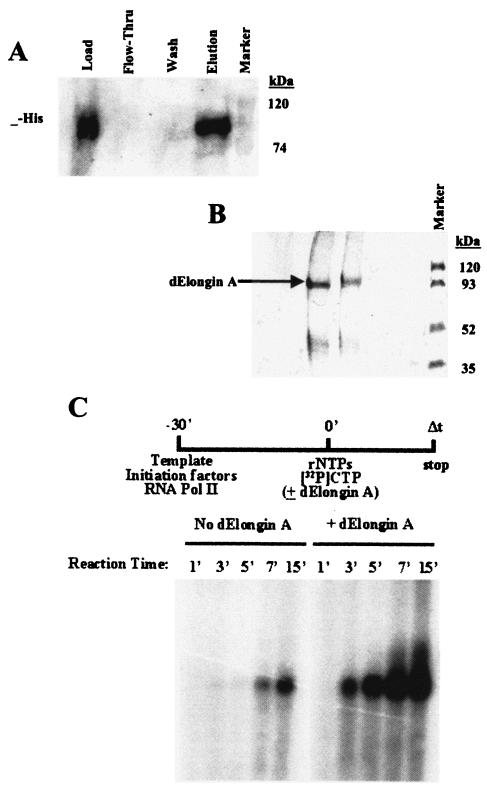

dEloA stimulates the rate of transcript elongation by Pol II in vitro.

To confirm that we had identified an elongin A homologue, we tested the activity of this protein in an in vitro transcription elongation assay. dEloA with an N-terminal six-histidine tag was expressed in E. coli and purified by nickel chromatography. Western analysis (Fig. 2A) and Coomassie staining (Fig. 2B) revealed a single polypeptide of ∼110 kDa, the size expected of full-length dEloA. Identity of the Coomassie-stained band was confirmed by tryptic digestion followed by MALDI-TOF analysis (data not shown). We then tested the ability of recombinant dEloA to stimulate Pol II elongation in an in vitro transcription assay. Promoter-specific transcription reactions were assembled with or without dEloA as described previously (14), and the accumulation of runoff transcripts after specific time points was examined by acrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. Figure 2C shows the dramatic stimulatory effect of dEloA on Pol II elongation. As with its mammalian counterparts, dEloA is capable of functionally interacting with Pol II in vitro, since it dramatically stimulates the rate of transcript accumulation in these reactions.

FIG. 2.

dEloA stimulates the catalytic rate of transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II in vitro. (A) Western blot analysis of purified recombinant dEloA. Recombinant dEloA was expressed in BL21(DE3)/pLysE E. coli and purified by nickel-chelating chromatography. Load, flow-through, wash, and elution fractions from the chelating column were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-His antibody (Invitrogen). (B) Silver-stained gel with fractions used in panel A. Recombinant dEloA was purified by nickel chromatography, and the identity of this purified protein was determined by MALDI-TOF analysis (data not shown). (C) Elongation activity of recombinant dEloA in vitro. Preinitiation complexes were formed at the adenovirus major late promoter in the presence of initiation factors (TBP, TFIIB, TFIIF, TFIIE, and TFIIH) and RNA Pol II. Transcription reactions were initiated by the addition of rNTPs in the presence or absence of recombinant dEloA as described in Materials and Methods. Reactions were stopped at the times indicated, and runoff transcripts were purified, sized by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and visualized by PhosphorImager analysis.

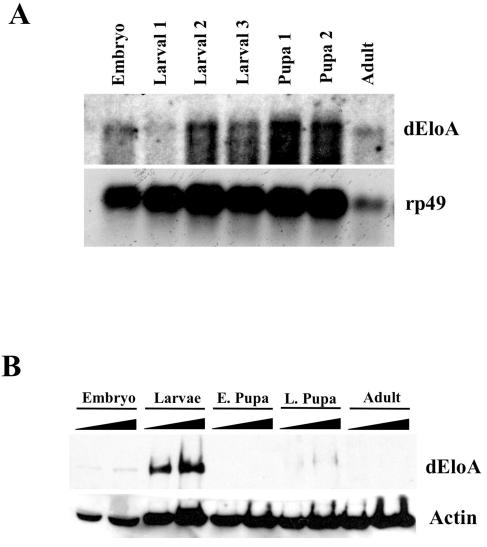

Developmental expression analysis of dEloA.

Previously, we characterized another Pol II elongation factor, Drosophila ELL (dELL). dELL is expressed at a high level in Drosophila embryos, and the transcript and protein are detectable throughout development. Interestingly, dELL is required for embryonic development, since dELL mutants die late in embryogenesis. Given this striking correlation, we examined the relative levels of expression of dEloA during the course of Drosophila development in order to try to gain insights into its physiological function(s). Northern blot analysis of total RNA isolated from wild-type organisms at each of the different developmental stages revealed that dEloA has a broad pattern of expression, with its peak around late larval stage to early pupation (Fig. 3A). Consistent with these data, dEloA protein levels also peak during the mid to late larval stages of development (Fig. 3B). Low levels of dEloA protein are detectable in embryos as well, and this is consistent with the observation that low levels of dEloA transcript are present during embryogenesis.

FIG. 3.

Developmental expression analysis of dEloA. (A) Northern blot analysis of total Drosophila RNA preparations at multiple stages of fly development. Developmental stages assayed include early embryo, first-, second-, and third-instar larval, pupal stages, and adult. With use of an antisense radiolabeled riboprobe against dEloA, dEloA mRNA expression was observed. Northern analysis of ribosomal protein 49 (rp49) indicates loading. (B) Developmental expression of the dEloA protein. Whole animal extracts were prepared from organisms at various developmental stages, and these extracts were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting using polyclonal antisera against dEloA (top panel) and antiactin as the protein loading control (bottom panel).

dEloA interacts with transcriptionally active RNA polymerase II in vivo.

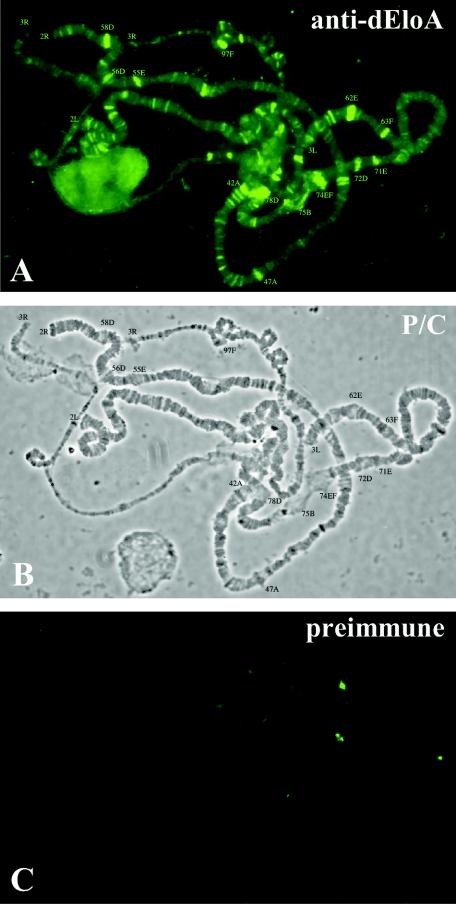

To determine whether dEloA is associated with elongating polymerase in the presence of chromatin components in vivo, we examined the distribution of dEloA on polytene chromosomes from the salivary glands of Drosophila third-instar larvae. dEloA is widely distributed throughout polytene chromosomes (Fig. 4A). Phase-contrast images of immunostained chromosomes were used to map the loci where dEloA protein is concentrated (Fig. 4B), and we observed relatively high dEloA levels at loci whose transcriptional activation is induced by the molting hormone ecdysone (e.g., 74EF and 75B) (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

dEloA localizes to a number of transcriptionally active loci on polytene chromosomes. (A) Immunofluorescence localization of dEloA on polytene chromosomes. Oregon R polytene chromosomes were prepared from salivary glands of third-instar larvae and probed with polyclonal antibodies raised against dEloA. Areas of strong dEloA immunolocalization were mapped as indicated. (B) Phase-contrast (P/C) image of immunostained chromosome. Mapped assignments of string dEloA binding sites are indicated. (C) Oregon R polytene chromosomes stained with preimmune antisera. Only background staining is visible when preimmune serum is used for immunostaining.

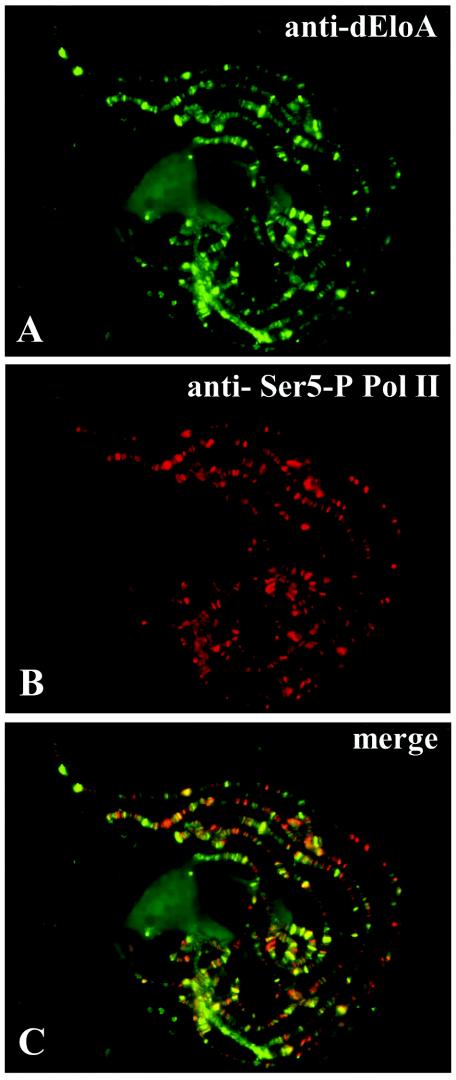

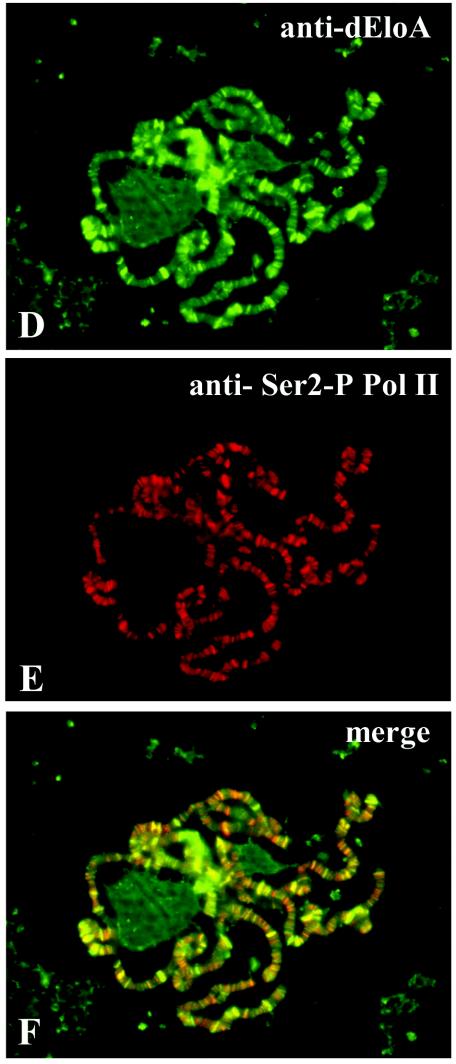

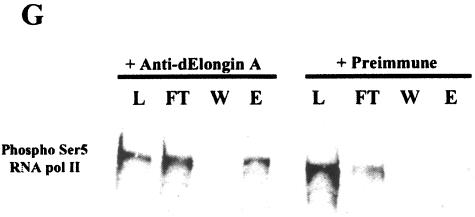

Pol II is phosphorylated on the conserved C-terminal domain (CTD) of the large subunit Rpb1 (6, 9, 22, 26, 41, 42). In vivo cross-linking studies with yeast have demonstrated that phosphorylation of serine 5 of the Pol II CTD is localized to promoter and promoter-distal regions of genes and is therefore a marker for early elongation complexes (22). However, phosphorylation of serine 2 of the CTD exhibits a nearly complementary pattern of localization and is found throughout the coding regions and nearer the 3′-end genes, suggesting that serine 2 phosphorylation is a mark for RNA polymerase engaged in the processive phases of transcription elongation. To determine whether dEloA colocalizes with elongating Pol II, chromosomes were stained simultaneously with dEloA polyclonal antisera and either monoclonal antibody against phospho-Ser5 Pol II or antibody against Phospho-Ser2 (Fig. 5). Merging these images, as shown in Fig. 5C and F, reveals that dEloA colocalizes extensively with Ser-2- and Ser5-modified Pol II, consistent with the model that dEloA interacts with transcribing Pol II on the DNA template in vivo. It is noteworthy, however, that the overlap between dEloA and phospho-Pol II is not seen at all transcriptionally active loci. This observation suggests that dEloA may have a more specific role in the regulation of a subset of active genes, as opposed to a general role in transcription.

FIG.5.

dEloA interacts with phosphorylated forms of RNA polymerase II in vivo. (A) Immunofluorescence detection of dEloA on Oregon R chromosomes. (B) Immunolocalization of Ser5-phospho-Pol II. (C) Overlay of panels A and B. Colocalization of green and red signals appears yellow. (D) Immunolocalization of dEloA on Oregon R chromosomes. (E) Chromosome in panel D was dual stained with antibody against Ser2-phospho-Pol II. (F) Overlay of panels D and E. Colocalization of signals appears yellow. (G) Whole-animal extracts were prepared from Oregon R third-instar larvae and subjected to immunoprecipitation with polyclonal antisera against dEloA or preimmune serum. Fractions from the procedure (L, load; FT, flow through; W, wash; E, elution) were then examined by Western blotting with antibodies against Ser5-phospho-Pol II. Pol II is enriched in the elution fraction when antibodies against dEloA are used in the immunoprecipitation.

While dEloA and phospho-Pol II exhibit a significant degree of colocalization on polytene chromosomes, these assays do not provide evidence of biochemical association between these proteins. To test whether dEloA is associated with Pol II in vivo, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments with whole-animal extracts from Drosophila third-instar larvae and examined the bound fractions for the presence of phospho-Pol II. As shown in Fig. 5G, phosphorylated Pol II is coimmunoprecipitated with dEloA, providing biochemical evidence that elongin A is associated with Pol II.

dEloA is required for metamorphosis.

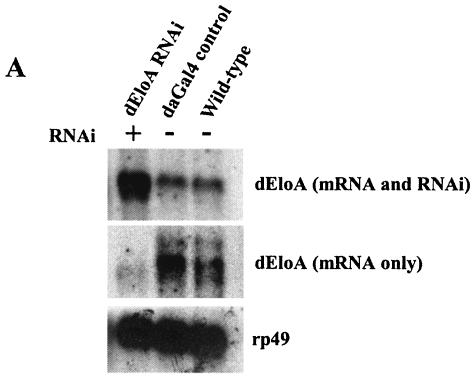

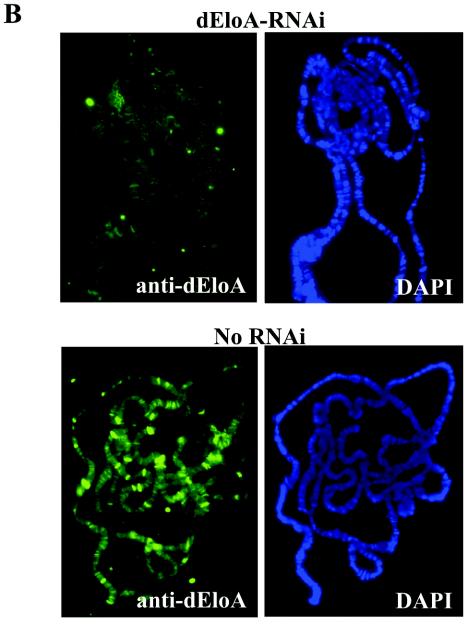

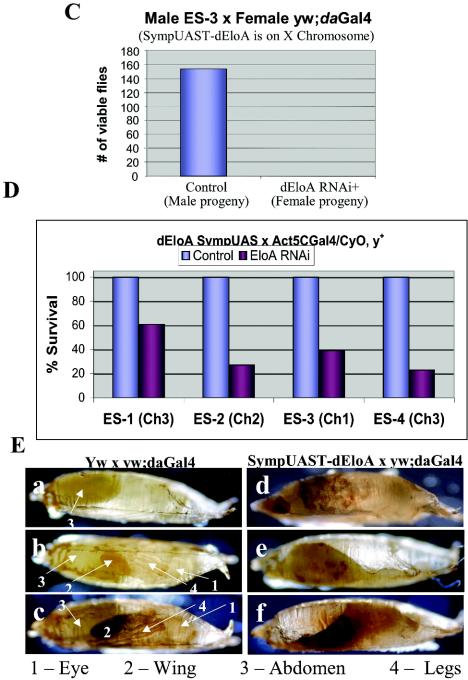

While much has been learned about the functions of elongation factors in the regulation of transcribing Pol II in vitro, the in vivo roles of many of these factors remain unresolved. While it appears that some elongation factors have redundant functions, it is clear that some of these factors are essential. To determine whether dEloA is required for normal development in Drosophila, we used an RNAi-based strategy to deplete dEloA mRNA and protein levels in developing flies. We cloned an internal portion of the dEloA cDNA (approximately 600 bp) into pSym-pUASTW, placing it between two convergent Gal4 upstream activation sequence promoters (15). Transgenic flies bearing this construct were then crossed to flies carrying transgenes expressing yeast Gal4 under control of either an actin5C or a daughterless promoter. The effects of RNAi targeted against dEloA are shown in Fig. 6. Northern blot analysis of total and poly(A)+ RNA from control and dEloA-RNAi third-instar larvae revealed that dEloA mRNA levels are dramatically reduced when RNAi is activated (Fig. 6A). To confirm that dEloA protein levels were also reduced in these animals, we compared the levels of dEloA on polytene chromosomes under normal and RNAi-activated conditions. dEloA is virtually undetectable on the chromosomes when RNAi is activated, while control chromosomes exhibit normal levels and distribution of the dEloA protein (Fig. 6B). Our Western analysis studies also demonstrated that the dEloA level is decreased upon activation of RNAi (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

dEloA is required for metamorphosis. (A) RNAi reduces dEloA mRNA in vivo. Total RNA was prepared from control and dEloA RNAi third-instar larvae, and dEloA mRNA or the dEloA RNAi levels were analyzed by Northern blotting. As shown, dEloA mRNA is dramatically reduced under conditions where RNAi is activated. (B) RNAi against dEloA dramatically reduces the levels of dEloA protein on polytene chromosomes. Shown are immunofluorescent images of dEloA (green) on polytene chromosomes obtained from dEloA-RNAi (RNAi is activated against dEloA) and control third-instar-larval salivary glands. Note that exposure times were the same for both images. 4′,6′-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining (blue) is used to visualize the chromosomes in these preparations. (C to E) Genetic data from dEloA RNAi crosses. (C) Reduction of dEloA results in lethality. Adult males carrying an X-linked SympUAST-dEloA transgene were crossed to virgin adult yw; daughterless Gal4 females (yw:daGal4). Male and female progeny were scored. Organisms in which RNAi is activated against dEloA (female progeny) did not survive. (D) actin 5C-Gal4/CyO y+ flies were crossed to adult virgin females for each of the three different pSym-pUASTW-dEloA transgenic flies. The number of CyO, y+ progeny was normalized to 100%, and the percentage of actin 5C-Gal4/SymUAST EloA flies was computed as percentage of expected. (E) Genetic data was generated similarly to that for (D), except that yw; actin5C Gal4 males were used in place of yw; daughterless Gal4. (E) Control pupae and pupae with RNAi against dEloA were photographed to demonstrate the differences in the formation of adult structures during the course of pupal development. (a to c) Early, middle, and late pupal stages of development in control pupae. (d to f) EloA RNAi pupae at identical stages. Selected structures are labeled.

We noticed that when we activated RNAi against dEloA, these organisms exhibited reduced viability compared to control animals. Using several different transgenic pSym-pUASTW-dEloA lines, we performed genetic analysis to determine whether dEloA is required for proper development. Genetic data from these experiments are summarized in Fig. 6C to E. For Fig. 6C, adult males carrying an X-linked SympUAST-dEloA transgene were crossed to virgin females carrying the Gal4 driver under control of the daughterless promoter. When RNAi is activated against dEloA (female progeny only), the majority of organisms are unable to survive to adulthood. To verify that this effect was not merely due to the insertion site of the SympUAST-dEloA transgene, we repeated the analysis using transgenic animals representing at least three independent transgene insertion sites. Crosses between virgin females carrying the pSym-pUASTW-dEloA transgene and males carrying the actin5C Gal4 driver yielded similar results (Fig. 6D). These data strongly suggest that dEloA is required for proper development in Drosophila.

Interestingly, we noticed that in all crosses, using four different pSym-pUASTW-dEloA transgene insertions, organisms in which dEloA levels were reduced by RNAi died invariantly during pupariation, with no observable effect on viability at other stages of development. The imaginal disks from dEloA-RNAi third-instar larvae exhibited normal size and morphology, indicating no general adverse effect on cell cycle progression in these tissues (data not shown). Close examination of the pupae generated in crosses where dEloA RNAi is activated revealed that these animals are unable to complete metamorphosis. There is no observable difference between the very early white prepupae (wpp) in dEloA RNAi and wild-type flies, but during the course of metamorphosis, significant defects in the dEloA-deficient pupae are evident. By the later stages of pupal development, control flies develop adult structures that are clearly visible through the pupal case (Fig. 6E, panels a to c), while the dEloA-deficient pupae lack any adult structures and have a shriveled appearance (panels d to f). We conclude that dEloA is an essential elongation factor that is required for development in Drosophila and may play a specific role in the developmental program regulating metamorphosis.

DISCUSSION

Biochemical data suggest that the elongin family of transcription factors can regulate transcription elongation by Pol II (2-4, 44). Here, we provide the first evidence that an elongin A family protein associates with hyperphosphorylated Pol II on chromosomes in vivo. These data strongly support a role for the elongin A proteins as Pol II elongation factors in vivo.

Functional redundancy of elongation factors has been suggested by the fact that several fall within the same biochemical class as elongin A (i.e., factors that increase the overall Km for nucleotides and/or Vmax of Pol II during transcription in vitro). Previously, we demonstrated that one of the proteins in this class, dELL, is essential in Drosophila and is not functionally redundant with other members (10). A recent report by Yamazaki et al. indicates that mammalian elongin A is not essential for viability of mouse ES cells but is important for proper cell cycle progression and expression of a specific subset of genes (43). Whether elongin A is required for normal mouse development is not known. However, there are three known elongin A homologues in mammalian cells, while only a single elongin A homologue exists in Drosophila. Thus, there may be functional redundancy among the mammalian elongin A homologues in vivo, although it has been shown that elongin A and elongin A3 do not have complementary properties in vitro (44). Another possibility is that multiple homologues in mammalian systems have tissue-specific expression and/or functions, some of which may be nonessential. A number of elongation factors appear to have evolved specialized functions in metazoans and are limiting for the expression of specific genes, with mutations that result in very specific phenotypes (10, 16, 21). Consistent with these observations, Northern blots for elongin A, elongin A2, and elongin A3 reveal differential expression at the tissue level (3, 44).

Understanding the role(s) of the different elongation factors with respect to specific gene expression and the regulation of developmental processes is of major interest. While the widespread distribution of dEloA on polytene chromosomes is consistent with a general role for this factor in transcription, our data also support a more specific role for dEloA in Drosophila development. As with dELL, dEloA is required for viability, although it is important to note that dELL is maternally loaded and that dELL-null flies die during late embryogenesis (10, 14). Animals lacking wild-type levels of dEloA die during the pupal stages of development, at or shortly after the stage in which dEloA mRNA and protein expression levels peak. Thus, dEloA may play an important role in metamorphosis, and a reduction in dEloA levels at the larval stage of development could affect the levels and/or timing of gene expression, resulting in failure to complete this process. It is important to recognize, however, that RNAi does not result in complete elimination of the dEloA protein. While levels of the protein are dramatically reduced, it is therefore possible that sufficient dEloA remains to permit viability during larval stages, whereas a true knockout may result in earlier death.

We have identified the first targets of elongin A regulation during animal development. We have shown that a loss of dEloA correlates with reduced steady-state levels of larval cuticle proteins (data not shown). The genes encoding these proteins are found within a coordinately regulated gene cluster that is activated specifically during late larval development (11, 39). Further, these genes are downstream targets of the hormone ecdysone. We have observed localization of dEloA to ecdysone-induced puff sites, also suggesting a role for dEloA in expression of ecdysone-induced genes. The shriveled appearance of pupae lacking wild-type levels of dEloA is interesting, given that the role of the larval cuticle proteins is to establish a barrier to prevent desiccation of the developing pupae. Future experiments should identify additional targets of dEloA in the Drosophila developmental program.

Given our observations of the pattern of expression and requirement of dEloA, it is an attractive possibility that dEloA is required for the proper regulation of specific genes involved in metamorphosis. Our evidence is consistent with the presumption that elongin A is an elongation factor in vivo, although the relationship between elongation activity and viability remains unclear. Overall, our study presented here demonstrates the following: (i) that elongin A associates with the elongating form of RNA polymerase II during transcriptional elongation; (ii) that not all elongation factors are created equal, i.e., they are not redundant, and each may have a tissue/gene-specific role during development; (iii) the elongation factor elongin A associates with the transcriptionally active developmental puff sites; and (iv) elongin A is required for coordinated regulation of gene expression and development. These novel in vivo studies on the role of elongin A as an RNA polymerase II elongation factor extend the important contribution played by Pol II elongation machinery in regulation of gene expression that is required for proper development.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dale Dorsett for intellectually stimulating conversations and the sharing of reagents and methods.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Science Foundation, MCB 0131414 (to J.C.E.), the American Cancer Society (RP69921801), and the National Institutes of Health (1R01CA089455) and a Mallinckrodt Foundation Award to A.S. A.S. is a scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aso, T., D. Haque, R. J. Barstead, R. C. Conaway, and J. W. Conaway. 1996. The inducible elongin A elongation activation domain: structure, function and interaction with the elongin BC complex. EMBO J. 15:5557-5566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aso, T., W. S. Lane, J. W. Conaway, and R. C. Conaway. 1995. Elongin (SIII): a multisubunit regulator of elongation by RNA polymerase II. Science 269:1439-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aso, T., K. Yamazaki, K. Amimoto, A. Kuroiwa, H. Higashi, Y. Matsuda, S. Kitajima, and M. Hatakeyama. 2000. Identification and characterization of elongin A2, a new member of the elongin family of transcription elongation factors, specifically expressed in the testis. J. Biol Chem. 275:6546-6552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradsher, J. N., K. W. Jackson, R. C. Conaway, and J. W. Conaway. 1993. RNA polymerase II transcription factor SIII. I. Identification, purification, and properties. J. Biol. Chem. 268:25587-25593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brower, C. S., S. Sato, C. Tomomori-Sato, T. Kamura, A. Pause, R. Stearman, R. D. Klausner, S. Malik, W. S. Lane, I. Sorokina, R. G. Roeder, J. W. Conaway, and R. C. Conaway. 2002. Mammalian mediator subunit mMED8 is an Elongin BC-interacting protein that can assemble with Cul2 and Rbx1 to reconstitute a ubiquitin ligase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:10353-10358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho, E. J., M. S. Kobor, M. Kim, J. Greenblatt, and S. Buratowski. 2001. Opposing effects of Ctk1 kinase and Fcp1 phosphatase at Ser 2 of the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain. Genes Dev. 15:3319-3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cockman, M. E., N. Masson, D. R. Mole, P. Jaakkola, G.-W. Chang, S. C. Clifford, E. R. Maher, C. W. Pugh, P. J. Ratcliffe, and P. H. Maxwell. 2000. Hypoxia inducible factor-alpha binding and ubiquitylation by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 275:25733-25741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen, L. H., and B. V. Gotchel. 1971. Histones of polytene and nonpolytene nuclei of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biol. Chem. 246:1841-1848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahmus, M. E. 1996. Reversible phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 271:19009-19012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eissenberg, J. C., J. Ma, M. A. Gerber, A. Christensen, J. A. Kennison, and A. Shilatifard. 2002. dELL is an essential RNA polymerase II elongation factor with a general role in development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:9894-9899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fristrom, J. W., R. J. Hill, and F. Watt. 1978. The procuticle of Drosophila: heterogeneity of urea-soluble proteins. Biochemistry 17:3917-3930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrett, K., T. Aso, J. Bradsher, S. Foundling, W. Lane, R. Conaway, and J. Conaway. 1995. Positive regulation of general transcription factor SIII by a tailed ubiquitin homolog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:7172-7176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrett, K., S. Tan, J. Bradsher, W. Lane, J. Conaway, and R. Conaway. 1994. Molecular cloning of an essential subunit of RNA polymerase II elongation factor SIII. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:5237-5241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerber, M., J. Ma, K. Dean, J. C. Eissenberg, and A. Shilatifard. 2001. Drosophila ELL is associated with actively elongating RNA polymerase II on transcriptionally active sites in vivo. EMBO J. 20:6104-6114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giordano, E., R. Rendina, I. Peluso, and M. Furia. 2002. RNAi triggered by symmetrically transcribed transgenes in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 160:637-648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo, S., Y. Yamaguchi, S. Schilbach, T. Wada, J. Lee, A. Goddard, D. French, H. Handa, and A. Rosenthal. 2000. A regulator of transcriptional elongation controls vertebrate neuronal development. Nature 408:366-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamura, T., D. Burian, Q. Yan, S. L. Schmidt, W. S. Lane, E. Querido, P. E. Branton, A. Shilatifard, R. C. Conaway, and J. W. Conaway. 2001. MUF1, a novel Elongin BC-Interacting leucine-rich repeat protein that can assemble with Cul5 and Rbx1 to reconstitute a ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:29748-29753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamura, T., D. M. Koepp, M. N. Conrad, D. Skowyra, R. J. Moreland, O. Iliopoulos, W. S. Lane, W. G. Kaelin, Jr., S. J. Elledge, R. C. Conaway, J. W. Harper, and J. W. Conaway. 1999. Rbx1, a component of the VHL tumor suppressor complex and SCF ubiquitin ligase. Science 284:657-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamura, T., S. Sato, D. Haque, L. Liu, W. G. J. Kaelin, R. C. Conaway, and J. W. Conaway. 1998. The Elongin BC complex interacts with the conserved SOCS-box motif present in members of the SOCS, ras, WD-40 repeat, and ankyrin repeat families. Genes Dev. 12:3872-3881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamura, T., S. Sato, K. Iwai, M. Czyzyk-Krzeska, R. C. Conaway, and J. W. Conaway. 2000. Activation of HIF1α ubiquitination by a reconstituted von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:10430-10435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keegan, B. R., J. L. Feldman, D. H. Lee, D. S. Koos, R. K. Ho, D. Y. R. Stainier, and D. Yelon. 2002. The elongation factors Pandora/Spt6 and Foggy/Spt5 promote transcription in the zebrafish embryo. Development 129:1623-1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komarnitsky, P., E. J. Cho, and S. Buratowski. 2000. Different phosphorylated forms of RNA polymerase II and associated mRNA processing factors during transcription. Genes Dev. 14:2452-2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavery, D., and U. Schibler. 1993. Circadian transcription of the cholesterol 7 alpha hydroxylase gene may involve the liver-enriched bZIP protein DBP. Genes Dev. 7:1871-1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall, N., and D. Price. 1992. Control of formation of two distinct classes of RNA polymerase II elongation complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:2078-2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller, T., K. Williams, R. W. Johnstone, and A. Shilatifard. 2000. Identification, cloning, expression, and biochemical characterization of the testis-specific RNA polymerase II elongation factor ELL3. J. Biol. Chem. 275:32052-32056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myers, L. C., C. M. Gustafsson, D. A. Bushnell, M. Lui, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, and R. D. Kornberg. 1998. The Med proteins of yeast and their function through the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain. Genes Dev. 12:45-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohh, M., C. W. Park, M. Ivan, M. A. Hoffman, T. Y. Kim, L. E. Huang, N. Pavletich, V. Chau, and W. G. Kaelin. 2000. Ubiquitination of hypoxia-inducible factor requires direct binding to the beta-domain of the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:423-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Price, D. H. 2000. P-TEFb, a cyclin-dependent kinase controlling elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:2629-2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Price, D. H., A. E. Sluder, and A. L. Greenleaf. 1989. Dynamic interaction between a Drosophila transcription factor and RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9:1465-1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reines, D., M. J. Chamberlin, and C. M. Kane. 1989. Transcription elongation factor SII (TFIIS) enables RNA polymerase II to elongate through a block to transcription in a human gene in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 264:10799-10809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reines, D., P. Ghanouni, W. Gu, J. Mote, Jr., and W. Powell. 1993. Transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II: mechanism of SII activation. Cell. Mol. Biol. Res. 39:331-338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reines, D., and J. Mote, Jr. 1993. Elongation factor SII-dependent transcription by RNA polymerase II through a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:1917-1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rio, D. C., F. A. Laski, and G. M. Rubin. 1986. Identification and immunochemical analysis of biologically active Drosophila P element transposase. Cell 44:21-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serizawa, H., R. C. Conaway, and J. W. Conaway. 1992. A carboxyl-terminal-domain kinase associated with RNA polymerase II transcription factor delta from rat liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:7476-7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shilatifard, A., R. C. Conaway, and J. W. Conaway. 2003. The RNA polymerase II elongation complex. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72:693-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shilatifard, A., D. R. Duan, D. Haque, C. Florence, W. H. Schubach, J. W. Conaway, and R. C. Conaway. 1997. ELL2, a new member of an ELL family of RNA polymerase II elongation factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:3639-3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shilatifard, A., W. S. Lane, K. W. Jackson, R. C. Conaway, and J. W. Conaway. 1996. An RNA polymerase II elongation factor encoded by the human ELL gene. Science 271:1873-1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sluder, A. E., A. L. Greenleaf, and D. H. Price. 1989. Properties of a Drosophila RNA polymerase II elongation factor. J. Biol. Chem. 264:8963-8969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snyder, M., J. Hirsh, and N. Davidson. 1981. The cuticle genes of drosophila: a developmentally regulated gene cluster. Cell 25:165-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spradling, A. C. 1986. P element mediated transformation, p. 175-197. In D. B. Roberts (ed.), Drosophila, a practical approach. IRL Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 41.Wada, T., T. Takagi, Y. Yamaguchi, D. Watanabe, and H. Handa. 1998. Evidence that P-TEFb alleviates the negative effect of DSIF on RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription in vitro. EMBO J. 17:7395-7403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamaguchi, Y., T. Wada, D. Watanabe, T. Takagi, J. Hasegawa, and H. Handa. 1999. Structure and function of the human transcription elongation factor DSIF. J. Biol. Chem. 274:8085-8092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamazaki, K., T. Aso, Y. Ohnishi, M. Ohno, K. Tamura, T. Shuin, S. Kitajima, and Y. Nakabeppu. 2003. Mammalian elongin A is not essential for cell viability but required for proper cell-cycle progression with limited alteration of gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 278:13585-13589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamazaki, K., L. Guo, K. Sugahara, C. Zhang, H. Enzan, Y. Nakabeppu, S. Kitajima, and T. Aso. 2002. Identification and biochemical characterization of a novel transcription elongation factor, Elongin A3. J. Biol. Chem. 277:26444-26451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]