Abstract

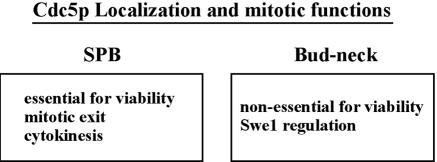

Budding yeast polo kinase Cdc5p localizes to the spindle pole body (SPB) and to the bud-neck and plays multiple roles during M-phase progression. To dissect localization-specific mitotic functions of Cdc5p, we tethered a localization-defective N-terminal kinase domain of Cdc5p (Cdc5pΔC) to the SPB or to the bud-neck with components specifically localizing to one of these sites and characterized these mutants in a cdc5Δ background. Characterization of a viable, SPB-localizing, CDC5ΔC-CNM67 mutant revealed that it is defective in timely degradation of Swe1p, a negative regulator of Cdc28p. Loss of BFA1, a negative regulator of mitotic exit, rescued the lethality of a neck-localizing CDC5ΔC-CDC12 or CDC5ΔC-CDC3 mutant but yielded severe defects in cytokinesis. These data suggest that the SPB-associated Cdc5p activity is critical for both mitotic exit and cytokinesis, whereas the bud neck-localized Cdc5p is required for proper Swe1p regulation. Interestingly, a cdc5Δ bfa1Δ swe1Δ triple mutant is viable but grows slowly, whereas cdc5Δ cells bearing both CDC5ΔC-CNM67 and CDC5ΔC-CDC12 grow well with only a mild cell cycle delay. Thus, SPB- and the bud-neck-localized Cdc5p control most of the critical Cdc5p functions and downregulation of Bfa1p and Swe1p at the respective locations are two critical factors that require Cdc5p.

The polo-like protein kinases (Plks) are a conserved subfamily of serine/threonine protein kinases that play pivotal roles in regulating various cellular and biochemical events at multiple stages of M phase. Members of the polo subfamily have been isolated from species as divergent as budding yeast and mammals. Plks are characterized by the presence of a distinct region of homology in the C-terminal noncatalytic domain, termed the polo-box. Studies with the budding yeast polo kinase Cdc5p have shown that the polo-box domain is critical for the localization of Cdc5p to the spindle pole body (SPB) and the daughter side of the bud-neck (48). In addition, the polo-box domain of mammalian polo-like kinase Plk1 was shown to be sufficient for the localization of this enzyme to the centrosomes, kinetochores, and midbody in cultured mammalian cells (20, 43). These data indicate that the role of the polo-box domain is conserved in targeting the catalytic activity of the polo kinases to specific subcellular locations.

In budding yeast, a disturbance in actin polarization or a defect in septin assembly delays G2/M transition by stabilizing Swe1p, a protein kinase which inhibits Cdc28p (Cdk1 of budding yeast) by phosphorylating a conserved tyrosine at position 19 (9). This delay results in a filamentous phenotype due to the inability of buds to switch from polarized to isotropic growth (6, 13, 25). It has been shown that both Hsl1p, a kinase closely related to Nim1p in other eukaryotic organisms, and its adaptor Hsl7p are required for the bud-neck localization and degradation of Swe1p (30, 46). Interestingly, overexpression of either wild-type or kinase-inactive CDC5 suppresses the growth defect associated with overexpression of SWE1 (7). In addition, the cdc5-3 hsl1Δ double mutant also showed a synthetic bud elongation and growth defect at a semipermissive temperature that was abolished by the introduction of swe1Δ (36). These data suggest that Cdc5p contributes to the Swe1p regulatory pathway and functions at a point upstream of Swe1p. Consistent with these observations, Cdc5p was shown to interact with Swe1p in a yeast two-hybrid assay (7, 31) and was shown to directly phosphorylate and negatively regulate Swe1p (40).

Prior to the onset of anaphase, polo kinases (both Plk1 and Cdc5) have been shown to phosphorylate cohesins to promote sister chromatid separation in both budding yeast and vertebrates (3, 12, 22, 50). Later in M phase in budding yeast, Cdc5p plays a critical role in activating the mitotic exit network (MEN), a pathway that leads to the inactivation of Cdc28p/Clb2p and the onset of cytokinesis. It has been shown that Cdc5p functions upstream of Tem1 by phosphorylating and negatively regulating Bfa1p (16, 19), which forms a two-component GTPase-activating protein with Bub2p to negatively regulate Tem1 (15). Similar to the Cdc5p localization, Tem1p, Bfa1p, and Bub2p have all been shown to localize to the SPB (37), suggesting the importance of the SPB in regulating mitotic exit. In addition, polo kinases appear to play important roles in regulating cytokinesis in diverse eukaryotic organisms (5, 34, 36, 49, 52), although the molecular mechanisms as to how they contribute to this event has not yet been elucidated.

Budding yeast polo kinase Cdc5p localizes to the SPB and bud-neck and plays multiple roles during M-phase progression. At present, there are no localization-specific alleles available that would allow one to address the localization-dependent mitotic functions of Cdc5p. In the present study, we generated localization-specific CDC5ΔC-fused chimera mutants and determined the role of Cdc5p at the SPB and the bud-neck. Analyses of these mutants led to the unexpected findings that the SPB-localized Cdc5p activity regulates both mitotic exit and cytokinesis, whereas the bud-neck-localized Cdc5p activity is important for proper Swe1p degradation. This protein-tethering approach may serve as a new method that can be applied to other proteins to determine the localization-specific functions at multiple subcellular localizations.

(This study was carried out by J.-E. Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Ph.D. degree from the Department of Biology, Dong-A University, Busan, South Korea.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain and plasmid construction.

Yeast strains and plasmids used in the present study are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. All deletion and epitope-tagged strains constructed in the present study were confirmed by PCR. Complete deletion of CDC5 (cdc5Δ::KanMX6 and cdc5Δ::HphMX4) ORF was generated by the one-step gene disruption method (28). Strain KLY3721 (cdc5Δ::KanMX6 + GAL1-EGFP-PLK1) was generated by deleting the CDC5 locus in the presence of PLK1 expression. To generate strains expressing a CDC5-GFP fusion under endogenous CDC5 promoter control (strains KLY4430, KLY4512, KLY4514, KLY4945, KLY4477, KLY4479, and KLY4511), a GFP::KanMX6 fragment obtained by PCR with pFA6a-GFP(S65T)-KanMX6 (28) as a template was integrated into the CDC5 locus. Strains KLY5208, KLY5209, and KLY5246 were generated similarly as described above by using pFA6a-3HA-KanMX6 (28) as a PCR template. To generate cnm67Δ strains expressing URA3::SPC42-GFP, NUD1-GFP::KanMX6, or SPC72-GFP::KanMX6 under their respective endogenous promoter control (strains KLY4953, KLY4917, and KLY4918, respectively), pKL2279 (SPC42-GFP) digested with XcmI or GFP::KanMX6 fragments obtained by PCR with pFA6a-KanMX6 (28) as a template were integrated into strain KLY4476 (IAY447 ade2−::ADE2) at the corresponding loci. Strains expressing Nud1p-HA3 (strain KLY4493), nud1-44p-HA3 (strain KLY5091), nud1-52p-HA3 (strain KLY5093), Spc72p-HA3 (strain KLY4495), and spc72-2p-HA3 (strain KLY5065) were generated by integrating HA3::HphMX4 fragments obtained by PCR with pSK2033 as a template into the respective loci. pSK2033 was generated by inserting a BglII-SacI fragment of HphMX4 obtained from pAG32 (a gift of Craig B. Bennett, NIEHS, Research Triangle Park, N.C.) into pFA6a-3HA-KanMX6 (28) digested with the corresponding enzymes. Strains expressing Spc98p-HA3 (strain KLY4661) and spc98-2p-HA3 (strain KLY5008) were obtained by integrating the C-terminal SPC98ΔN-5xGly-HA3 plasmid (pKL2645) after XbaI digestion. To generate swe1Δ::LEU2, a 3.5-kb BamHI-HindIII fragment obtained from pSWE1-10g (9) was directly transformed into the respective strains. To construct strains KLY4793 and KLY4795, pRS304-SWE1 partially digested with XbaI or pRS304 digested with BsgI, respectively, was integrated into strain KLY4753 (cdc5Δ swe1Δ + pCDC5ΔC-CNM67) at the TRP1 locus. Strain KLY4641 (cdc5Δ::HphMX4 bfa1Δ::his5+ + pGAL1-EGFP-PLK1) was generated by crossing strain KLY2491 (MATα bfa1Δ::his5+) with strain KLY4439 (MATa cdc5Δ::HphMX4 + pGAL1-EGFP-PLK1). Strains KLY4787, KLY4798, KLY4789, KLY5012, and KLY5129 possess an integrated copy of LEU2: YFP-CDC10 (pSK1060) to visualize the septin ring structures. Strain KLY5419 was generated by culturing strain KLY4798 on a 5-fluoroorotic acid (8)-containing plate to select against the presence of pSK1362 (URA3:GAL1-EGFP-PLK1). Strains KLY5423 and KLY5372 were generated by integrating a control URA3-containing vector pRS306 digested with NcoI. Strains KLY5424 and KLY5373 were created by integrating RDB608 (a gift from Raymond J. Deshaies, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, Calif.) digested with EcoRV, whereas strains KLY5425 and KLY5374 were constructed by integrating RDB609 (a gift from Raymond J. Deshaies) digested with the same restriction enzyme.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| KLY1546 | MATahis3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 | Lab stocka |

| KLY3721 | MATacdc5Δ::KanMX6 + YCplac33-GAL1-EGFP-PLK1 | This studyb |

| JB811 | MATaprb1 pep4-3 trp1 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 | D. Kellogg |

| #822 | MATahis3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3 SPC42:spc42-10i | J. Kilmartin |

| KLY4430 | #822 ade2:ADE2 CDC5-GFP::kanMX6 | This study |

| KLY2346 | MATanud1Δ::his5+TRP1:nud1-44 | This studyc |

| KLY4512 | KLY2346 CDC5-GFP::KanMX6 | This study |

| KLY2349 | MATanud1Δ::his5+TRP1:nud1-52 | This studyc |

| KLY4514 | KLY2349 CDC5-GFP::KanMX6 | This study |

| KLY2355 | MATaspc72-2::HIS3 | This studyc |

| KLY4945 | KLY2355 CDC5-GFP::KanMX6 | This study |

| TNY64-5C | MATα ade2-loc ade3Δ can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 lys2Δ::HIS3 trp1-1 spc97-114 + pHS26 (2μ ADE3, LYS2, SPC110) | T. Davis |

| KLY4477 | TNY64-5C CDC5-GFP::KanMX6 | This study |

| KLY4440 | MATaade2-101 och his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 lys2-801am trp1Δ63 ura3-52 spc98-2 | M. Winey |

| KLY4479 | KLY4440 CDC5-GFP::KanMX6 | This study |

| IAY447 | cnm67Δ::his5+ | J. Kilmartin |

| KLY4511 | IAY447 ade2::ADE2 CDC5-GFP::KanMX6 | This study |

| KLY4953 | IAY447 ade2::ADE2 SPC42-GFP::URA3 | This study |

| KLY4917 | IAY447 ade2::ADE2 NUD1-GFP::KanMX6 | This study |

| KLY4918 | IAY447 ade2::ADE2 SPC72-GFP::KanMX6 | This study |

| KLY4101 | CDC5-Myc13::KanMX6 | This study |

| KLY4493 | KLY4101 NUD1-HA3::HphMX4 | This study |

| KLY5091 | KLY2346 nud1-44-HA3::HphMX4 | This study |

| KLY5093 | KLY2349 nud1-52-HA3::HphMX4 | This study |

| KLY4495 | KLY4101 SPC72-HA3::HphMX4 | This study |

| KLY5065 | KLY2355 spc72-2-HA3::HphMX4 | This study |

| KLY4661 | KLY4101 SPC98-(Gly)3-HA3::HphMX4 | This study |

| KLY5008 | KLY4440 spc98-2-(Gly)3-HA3::HphMX4 | This study |

| KLY4645 | KLY1546 cnm67Δ::his5+ | This study |

| KLY4429 | KLY1546 + YCplac33-GAL1-EGFP-PLK1 | This study |

| KLY4439 | KLY4429 cdc5Δ::HphMX4 | This study |

| KLY4522 | KLY4439 swe1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| KLY4753 | KLY4522 + pRS313-YFP-CDC5ΔC-CNM67 | This study |

| KLY4793 | KLY4753 TRP1:pRS304-SWI1 | This study |

| KLY4795 | KLY4753 TRP1:pRS304 | This study |

| KLY4641 | MATacdc5Δ::HphMX4 bfa1Δ::his5+ + YCplac33-GAL1-EGFP-HA-PLK1 | This study |

| KLY4787 | KLY4439 LEU2:YFP-CDC10 + YCplac22-CDC5 | This study |

| KLY4798 | KLY4641 LEU2:YFP-CDC10 + pRS314-CDCΔC-CDC12 | This study |

| KLY4789 | KLY4439 LEU2:YFP-CDC10 + pRS314-CDC5ΔC-CNM67 | This study |

| KLY5012 | KLY4439 + pRS315-CDC5ΔC-CNM67 + pRS314-CDC5ΔC-CDC12 | This study |

| KLY5129 | KLY4641 + pRS315-CDC5ΔC-CNM67 + pRS314-CDC5ΔC-CDC12 | This study |

| KLY5419 | MATacdc5Δ::HphMX4 bfa1Δ::his5+LEU2:YFP-CDC10 + pRS314-CDC5ΔC-CDC12 | This study |

| KLY5423 | KLY5419 URA3:pRS306 | This study |

| KLY5424 | KLY5419 URA3:pRS306-GAL1-SIC1 | This study |

| KLY5425 | KLY5419 URA3:pRS306-GAL1-SIC1-4A | This study |

| KLY5366 | KLY4439 LEU2:MYO1-GFP + pRS314-CDC5 | This study |

| KLY5370 | KLY4641 LEU2:MYO1-GFP + pRS314-CDC5ΔC-CDC12 | This study |

| KLY1083 | MATaURA3:EGFP-CDC5ΔN | 49d |

| KLY4816 | MATacdc5Δ::HphMX4 bfa1Δ::his5+ pRS314-BFA1 + YCplac111-CDC5-GFP | This study |

| KLY5372 | KLY4816 URA3:pRS306 | This study |

| KLY5373 | KLY4816 URA3:pRS306-GAL1-SIC1 | This study |

| KLY5374 | KLY4816 URA3:pRS306-GAL1-SIC1-4A | This study |

| KLY5709 | MATacdc5Δ::HphMX4 swe1Δ::LEU2 + YCplac33-GAL1-EGFP-PLK1 | This study |

| KLY5713 | MATacdc5Δ::HphMX4 bfa1Δ::his5+swe1Δ::LEU2 + YCplac33-GAL1-EGFP-PLK1 | This study |

| KLY5208 | MATacdc5Δ::HphMX4 SCC1-HA3::KanMX6 + YCplac111-EGFP-CDC5 | This study |

| KLY5209 | MATacdc5Δ::HphMX4 SCC1-HA3::KanMX6 + YCplac33-GAL1-EGFP-PLK1 + pRS314-CDC5ΔC-CNM67 | This study |

| KLY5246 | MATacdc5Δ::HphMX4 bfa1Δ::his5+SCC1-HA3::KanMX6 + YCplac33-GAL1-EGFP-PLK1 + pRS315-CDC5ΔC-CDC12 | This study |

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Name | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pSK754 | YCplac111, EGFP-CDC5 | See text |

| pCJ232 | YCplac111, EGFP-CDC5ΔC | 35 |

| pKL2420 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-BBP1 | See text |

| pKL2422 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-MPS2 | See text |

| pKL2419 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-CDC31 | See text |

| pKL2418 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-KAR1 | See text |

| pKL2425 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-SPC29 | See text |

| pKL2426 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-SPC42 | See text |

| pKL2430 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-CNM67 | See text |

| pKL2428 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-NUD1 | See text |

| pKL2423 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-SPC72 | See text |

| pKL2432 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-SPC97 | See text |

| pKL2429 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-SPC98 | See text |

| pKL2520 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-SPC110 | See text |

| pKL2434 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-BN15 | See text |

| pKL2435 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-CDC3 | See text |

| pKL2436 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-CDC10 | See text |

| pKL2437 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-CDC11 | See text |

| pKL2438 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-CDC12 | See text |

| pSK1362 | YCplac33, GAL1-EGFP-PLK1 | See text |

| pKL2772 | pRS315, YFP-CDC5ΔC-CDC5ΔN | See text |

| pKL2504 | pRS316, SPC42 | See text |

| pKL2640 | pRS315, NUD1 | See text |

| pXC214 | YCp-LEU2, SPC72 | 10 |

| pKL2702 | pRS315, SPC97 | See text |

| pHS89 | pRS316, SPC98 | M. Winey |

| pKL2279 | pRS306, SPC42-GFP | See text |

| pKL2589 | pRS315, CNM67 | See text |

| pKL2590 | pRS316, CNM67 | See text |

| pKL2497 | pGEX-KG, BBP1 | 35 |

| pKL2496 | pGEX-KG, MPS2 | 35 |

| pKL2467 | pGEX-KG, CDC31 | See text |

| pKL2463 | pGEX-KG, SPC42 | See text |

| pKL2471 | pGEX-KG, CNM67 | See text |

| pKL2465 | pGEX-KG, NUD1 | See text |

| pKL2469 | pGEX-KG, SPC72 | See text |

| pKL321 | YCplac22, CDC5 | See text |

| pKL743 | YCplac111, CDC5 | See text |

| pKL1665 | pRS313, CDC5 | See text |

| pKL2690 | pRS316, CDC5 | See text |

| pKL1171 | YEp351, CDC5 | See text |

| pKL2692 | YEp352, CDC5 | See text |

| pKL2519 | pRS314, SWE1 | See text |

| pKL2636 | pRS313, YFP-CDC5ΔC-CNM67 | See text |

| pKL2728 | pRS304, SWE1 | See text |

| pKL2567 | pRS314, BFA1 | See text |

| pSK1060 | pUC19-LEU2, YFP-CDC10 | 49 |

| pKL2453 | pRS315, CDC5ΔC-CNM67 | See text |

| pKL2732 | pRS314, CDC5ΔC-CDC12 | See text |

| pKL2563 | pRS314, CDC5ΔC-CNM67 | See text |

| RDB608 | pRS306, GAL1-SIC1 | 53 |

| RDB609 | pRS306, GAL1-SIC1-4A | 53 |

| pSK1052 | pUC19-LEU2, Myo1-GFP | 49 |

pSK754 was constructed by inserting a EGFP fragment into the PpuMI site in the N-terminal region of CDC5 in YCplac111-CDC5. To generate CDC5ΔC-fused chimera constructs (pKL2420-pKL2438), pKL2772 (pRS315-Flag-YFP-CDC5), which expresses the recombinant protein under endogenous CDC5 promoter control, was first generated. pKL2772 has an insertion of a BssHII site at amino acid 500 in CDC5 open reading frame (ORF) and as a result contains four additional amino acid (SGAR) residues. To construct CDC5ΔC-NUD1 (pKL2428) and CDC5ΔC-SPC72 (pKL2423), a MluI-NheI fragment containing the respective ORF was cloned into pKL2772 digested with the corresponding enzymes. All other chimera constructs were generated by inserting BssHII-NheI fragments containing the respective ORFs into pKL2772 digested with the corresponding enzymes. All of the fusion constructs possess the full-length ORF with the CDC5ΔC in the N-terminal domain. To generate pSK1362, a EcoRI-SphI fragment obtained from pSK1267 (49) was inserted into YCplac33 digested with corresponding enzymes. pKL2504 was generated by inserting a PCR fragment containing full-length SPC42 into pRS316 at the XbaI site. An ApaI-NotI fragment containing full-length NUD1 was inserted into pRS315 at the corresponding sites, creating plasmid pKL2640. pKL2702 was generated by inserting a XhoI-SstI fragment obtained from pTN3 (a gift from T. Davis, University of Washington, Seattle) into pRS315 digested with corresponding enzymes. pKL2279 was constructed by cloning an EcoRI-NotI fragment derived from pIA29 (a gift from J. V. Kilmartin, Medical Research Council, Cambridge, United Kingdom) into pRS306 digested with corresponding enzymes. pKL2589 and pKL2590 were generated by inserting a NotI-XhoI fragment obtained from pRS426-CNM67 (a gift from M. Winey, University of Colorado, Boulder) into pRS315 and pRS316, respectively, at the corresponding sites. Plasmids pKL2467, pKL2471, and pKL2469 were constructed by inserting an BspEI (end filled)-XhoI fragment containing the full-length respective ORFs into pGEX-KG vector digested with XbaI (end filled) and XhoI. To generate pKL2463 and pKL2465, PCR fragments containing the full-length SPC42 and NUD1, respectively, were digested with AvrII and SacI and then cloned into pGEX-KG digested with XbaI and SacI. To construct pKL321, pKL743, pKL1665, pKL2690, pKL1171, and pKL2692, an XbaI fragment containing full-length CDC5 was inserted into the respective vectors at the same site. A BamHI-PstI fragment from pJM1023 (a gift from D. J. Lew, Duke University, Durham, N.C.) was inserted into pRS314 or pRS304 at the corresponding sites, creating pKL2519 or pKL2728, respectively. pKL2636 was generated by inserting a NgoMIV-BamHI fragment containing Flag-YFP-CDC5ΔC-CNM67 into pRS313 at the corresponding site. To construct pKL2567, a PstI-SacI fragment containing full-length BFA1 was inserted into pRS314 at the corresponding enzyme sites. To generate pKL2453, an NsiI-SmaI fragment that contains FLAG-YFP-CDC5 from pKL2430 was replaced with an endogenous CDC5 fragment digested with the corresponding enzymes. To generate pKL2732, a BssHII-NheI fragment containing the ORF of CDC12 was ligated with a pRS314-CDC5ΔC fragment digested with the corresponding enzymes. An NgoMIV-SmaI fragment containing CDC5ΔC-CNM67 was inserted into pRS314 at the corresponding sites, creating plasmid pKL2563. Detailed maps for the constructs described here will be provided upon request.

Growth conditions, flow cytometry, and zymolyase treatment.

Yeast cell culture and transformations were carried out by standard methods (44). For cell cycle synchronization, MATa cells were arrested with 5 μg of an α mating pheromone (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.)/ml at 23°C for cnm67Δ and at 30°C for CDC5ΔC-CNM67 swe1Δ and then released. To analyze cell cycle progression, flow cytometry analyses were carried out by using the FACScaliber (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.), and the obtained data were analyzed with Flowjo software (Becton Dickinson). Treatment of the connected cells with zymolyase was performed as described previously (27). Connected cells were counted after observing loss of the refractile appearance.

Immunocomplex kinase assays and immunoblotting analyses.

To measure the Flag-YFP-Cdc5p-associated kinase activity, cellular lysates were prepared and spun at 15,000 × g for 10 min, and the resulting supernatants (S15) were subjected to immunocomplex kinase assays with anti-Flag antibody (Sigma) as described previously (23).

To examine the levels of protein expression, total cellular proteins were prepared by vortexing the cell pellets with approximately equal volumes of glass beads and 2× Laemmli sample buffer. Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-10% PAGE) (4) and subjected to immunoblotting analyses with anti-HA.11 (Babco, Richmond, Calif.), anti-Clb2 (a gift from David O. Morgan, University of California-San Francisco), or anti-Cdc28p (a gift from R. Deshaies, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena) antibodies. To determine the amount of anti-Flag immunoprecipitates, subsequent immunoblotting analyses were carried out with anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) antibody (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.). Proteins that interact with antibodies were detected by using an enhanced chemiluminescence Western detection system (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

Preparation of recombinant proteins and in vitro protein-protein interactions.

Recombinant GST-Bbp1p, GST-Mps2p, GST-Cdc31p, GST-Spc42p, GST-Cnm67p, GST-Nud1p, and GST-Spc72p proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) and partially purified by using glutathione-Sepharose beads (Sigma). For in vitro binding studies, S15 cellular lysates obtained from Sf9 cells expressing Cdc5p-Flag were incubated with the purified GST-ligands in TBSN (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 120 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40. 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA) buffer at 4°C for 1 h. The resin was washed with the binding buffer five times, and bound proteins were eluted with SDS-sample buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting analyses with anti-Flag antibody (Sigma).

Fluorescence microscopy and time-lapse imaging.

Localization of GFP- or yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-fused proteins was examined after cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde. To reveal the membrane morphology, cells were stained with DiI (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) as described previously (49). Fluorescent and differential interference contrast images were collected with a Zeiss LSM510 confocal system by using an Axiovert 100M microscope. Time-lapse analyses were carried out essentially as described previously (24).

RESULTS

Generation of localization-specific Cdc5pΔC chimera mutants.

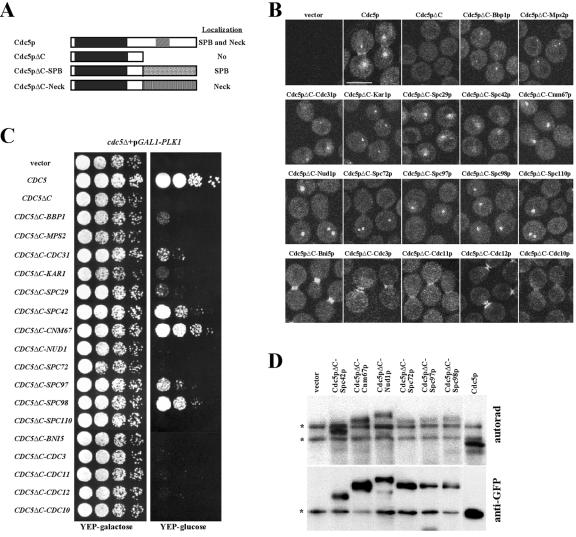

To investigate the localization-specific Cdc5p functions, we generated Cdc5pΔC-fused chimera mutants by tethering the localization-defective catalytic domain of Cdc5p (Cdc5pΔC) under endogenous promoter control to the SPB (for reviews, see references 2 and 38) or the bud-neck (17) with components known to localize to one of these sites (Fig. 1A). The resulting constructs were then transformed into a wild-type strain KLY1546, and the specific localization of the encoded fusion proteins was examined by fluorescence microscopy. Consistent with the previous observation (48), GFP-Cdc5p localized to the SPB and weakly to the bud-neck, whereas Cdc5p lacking the polo-box domain (Cdc5pΔC) yielded only diffused signals (Fig. 1B). Under the same conditions, Cdc5pΔC fused with components at the SPB (collectively, Cdc5pΔC-SPB) or the bud-neck (collectively, Cdc5pΔC-neck) localized to the SPB or bud-neck, respectively, with various degrees of localization efficiency (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

(A) Structures of Cdc5p and Cdc5pΔC-fused chimera proteins. For Cdc5p, a black box in the N-terminal domain denotes the kinase domain, and a hatched box denotes the highly conserved polo-box motif in the C-terminal noncatalytic domain. Cdc5p lacking the C-terminal domain (Cdc5pΔC) contains amino acid residues 1 to 500. ORFs encoding components at the SPB or the bud-neck were C terminally fused to the CDC5ΔC. The predicted localizations of these constructs are indicated. (B) To examine the localization of various Cdc5pΔC-chimera, YFP-fused CDC5ΔC-chimera constructs were transformed into a wild-type KLY1546 and cultured overnight at 23°C before fixation and examination by YFP fluorescence. Bar, 5 μm. (C) The ability of the CDC5ΔC-chimera constructs to complement the cdc5Δ defect, the same constructs used in panel B were transformed into strain KLY3721 (cdc5Δ + pGAL1-PLK1) and cultured overnight. These cultures were serially diluted and spotted onto either YEP-galactose or YEP-glucose plates at 30°C. (D) To determine the kinase activities of the indicated chimera proteins, a protease-negative strain (JB811) transformed with the indicated constructs was subjected to immunocomplex kinase assays with anti-Flag antibody. Reaction mixtures were separated in SDS-PAGE, transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and then exposed to detect the autophosphorylation activities (upper panel). The same blot was subjected to immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibody to determine the amount of immunoprecipitated Flag-YFP-Cdc5p or the corresponding chimera proteins (lower panel). Asterisks indicate coimmunoprecipitated bands (upper panel) and a cross-reacting protein with anti-Flag antibody (lower panel).

We then examined the ability of these fusion proteins to functionally complement the loss of CDC5 function. To this end, fusion constructs were introduced into a cdc5Δ strain, in which viability was maintained by GAL1-driven expression of a cDNA encoding mammalian polo kinase PLK1 (KLY3721), and then the ability of the chimera to complement the inviability of the cdc5Δ cells was examined on glucose medium. Provision of CDC5ΔC-CNM67 efficiently rescued the lethality of the cdc5Δ mutation (Fig. 1C). CDC5ΔC-SPC42, CDC5ΔC-SPC98, and CDC5ΔC-SPC97 also rescued the cdc5Δ defect at somewhat reduced levels (Fig. 1C). However, none of the CDC5ΔC-neck chimeras rescued the cdc5Δ defect (Fig. 1C). When these constructs were expressed in a wild-type KLY1546, none of them induced a detectable level of growth inhibition or morphological defect (data not shown), suggesting that the expressed proteins do not interfere with the function of either the endogenous Cdc5p or the respective endogenous proteins fused to Cdc5pΔC.

Next, we examined whether the ability of a subset of CDC5ΔC-SPB chimera constructs to rescue the cdc5Δ lethality reflects differences in expression levels or kinase activities. Immunoblotting analyses of total cellular lysates failed to detect the Cdc5pΔC-SPB chimera proteins (data not shown). However, immunocomplex kinase assays performed with the same amount of cellular lysates for each chimera mutant revealed that the expression levels and kinase activities of these mutants were similar, although several of them exhibited a few fold lower activity than that of the endogenous Cdc5p (Fig. 1D). These data indicate that all of the Cdc5ΔC-SPB chimera proteins examined are catalytically active, but only a subset of them is capable of suppressing the cdc5Δ lethality. Thus, targeting the catalytic activity of Cdc5pΔC to a specific region within the SPB appears to be important for the Cdc5p function(s) essential for viability.

Importance of Cnm67p-dependent SPB components or structures for efficient localization of Cdc5p to the SPB.

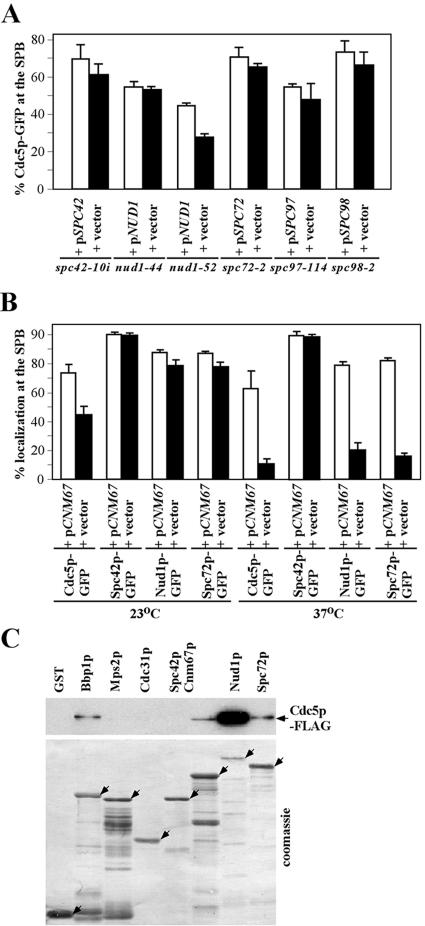

Cdc5p localizes to the SPB in cells treated with nocodazole (data not shown), suggesting that Cdc5p localizes to the SPB in a microtubule-independent manner. It has been shown that Bbp1p, which localizes to the periphery of the central plaque and plays a critical role in SPB duplication (42), is important but not fully accountable for Cdc5p localization (35). Thus, we examined whether the proper localization of Cdc5p to the SPB requires additional components at the SPB. To this end, various central and outer plaque SPB mutants expressing Cdc5p-GFP under endogenous CDC5 promoter control were transformed with either control vector or a centromeric plasmid containing the corresponding wild-type locus. The resulting transformants were then cultured at the nonpermissive temperature to examine the efficiency of Cdc5p-GFP localization by fluorescent signals. At the nonpermissive temperature, Cdc5p localization was partially but significantly impaired in the nud1-52 mutant but largely not influenced in spc42-10i, nud1-44, spc72-2, spc97-114, and spc98-2 mutants (Fig. 2A). The undiminished Cdc5p-GFP localization to the SPB in several of these mutants prompted us to examine the levels of these mutant proteins at the restrictive temperature. In comparison to those of respective wild-type proteins, all four mutant proteins (nud1-44p, nud1-52p, spc72-2p, and spc98-2p) examined exhibited a few fold decrease in protein level with no detectable slower-migrating isoform(s) at the nonpermissive temperature (see Fig. S1 at http://home.ccr.cancer.gov/metabolism/klee/mcb_vol24_No22_supplementary). These observations suggest that either the observed decrease in protein expression levels and the loss of posttranslational modifications are not sufficient to induce delocalization of Cdc5p from the SPB or these components are not solely responsible for the Cdc5p-GFP localization to the SPB.

FIG. 2.

Proper localization of Cdc5p to the SPB requires Cnm67p-dependent structures. (A) Various SPB mutants bearing either control vector or centromeric plasmids containing the corresponding wild-type loci were cultured at 37°C for 1.5 to 2 h, fixed, and then examined for Cdc5p localization by GFP fluorescence. Error bars indicate the standard deviations. (B) cnm67Δ cells expressing CDC5-GFP, SPC42-GFP, NUD1-GFP, or SPC72-GFP were transformed with either vector or a centromeric CNM67 plasmid. The resulting transformants were cultured at either 23 or 37°C for 1.5 h, and then the localization of the respective proteins was examined after fixation. Error bars indicate the standard deviations. (C) In vitro binding studies were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. After SDS-PAGE, the amounts of bound Cdc5p-Flag were determined by immunoblotting with anti-Flag antibody (upper panel), while the amounts of the bacterially expressed, partially purified, GST or GST-fused ligands were determined by staining with Coomassie blue (lower panel). Arrows indicate the GST and GST-fused full-length ligands.

The cnm67Δ mutant exhibits a temperature-sensitive growth defect (see Fig. 3B), suggesting that loss of CNM67 function induces an additional uncharacterized defect at an elevated temperature. Interestingly, Cdc5p-GFP localization was partially impaired at 23°C and severely disrupted at 37°C in cnm67Δ (Fig. 2B), indicating that a large fraction of Cdc5p delocalizes from the SPB as a result of the temperature-sensitive cnm67Δ defect. Thus, we also examined the localization of other SPB components (i.e., one central plaque component Spc42p-GFP and the other two outer plaque components, Nud1p-GFP and Spc72p-GFP) in cnm67Δ under the same conditions. At 23°C, all three proteins (Spc42p, Nud1p, and Spc72p) efficiently localized to the SPB. At 37°C, however, the localization of the outer plaque components, Nud1p and Spc72p, was greatly diminished although not completely eliminated, whereas the localization of the central plaque component, Spc42p, remained unaffected (Fig. 2B). These observations suggest that cnm67Δ induces a temperature-sensitive SPB defect that results in the loss of outer plaque components. Taken together, these data suggest that temperature-sensitive delocalization of Cdc5p from the SPB in cnm67Δ is due to the loss of Cnm67p-dependent outer plaque SPB component(s) or structure(s) at the elevated temperatures.

FIG. 3.

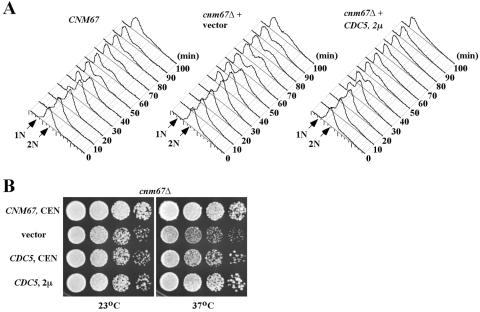

Suppression of the cnm67Δ defect by overexpression of CDC5. (A) Strains KLY4855 (CNM67), KLY4856 (cnm67Δ + vector), and KLY4858 (cnm67Δ + 2μ CDC5) were arrested by α-factor treatment at 23°C and released into nocodazole-containing medium for 1 h at 37°C to rearrest cells at prometaphase. Cells were then washed and released into an α-factor containing medium at 37°C. Samples were harvested at the indicated time points and subjected to flow cytometry analyses. (B) Suppression of the cnm67Δ growth defect by CDC5. Strain KLY4645 (cnm67Δ) transformed with the indicated plasmids was cultured overnight, serially diluted, spotted onto YEP-glucose plates, and then incubated at the indicated temperatures.

We next sought to determine whether Cdc5p interacts physically with outer plaque SPB component(s). Various recombinant glutathione S-transferase (GST)-fused SPB components expressed in E. coli were partially purified and used as ligands. Bbp1p, which interacts with Cdc5p both in yeast two-hybrid and in vitro analyses (35), was also expressed as a GST-fused form and included as a comparison. As observed previously (35), GST-Bbp1p, but not GST-Mps2p, interacted with Cdc5p. Under the same conditions, GST-Nud1p interacted strongly with Cdc5p, whereas Cnm67p and Spc72p interacted weakly (Fig. 2C). We were not able to examine GST-Spc97p and GST-Spc98p because of a failure to express these proteins (data not shown). These observations, together with Cdc5p localization data in various SPB mutants, suggest that a large fraction, but not all, of the Cdc5p may localize to the SPB through the interaction with Nud1p. However, under various conditions, we failed to coimmunoprecipitate Nud1p, Bbp1p, or any of the other SPB components with Cdc5p from growing yeast cell lysates (data not shown), suggesting that the interactions between Cdc5p and components at the SPB are likely transient.

Overexpression of CDC5 suppresses the cnm67Δ-dependent mitotic delay.

Impaired Cdc5p localization to the SPB in cnm67Δ suggests that the cnm67Δ mutant may be defective in mitotic progression and that the provision of CDC5 may suppress this defect. To examine these possibilities, an isogenic wild-type CNM67 (strain KLY4855) and a cnm67Δ mutant transformed with either vector (strain KLY4856) or a multicopy CDC5 plasmid (strain KLY4858) were first arrested at prometaphase with nocodazole at 23°C. Cultures were then shifted to 37°C for 1 h to reveal the temperature-sensitive cnm67Δ defect, before release into an α-factor-containing prewarmed (37°C) medium. Compared to the wild-type, cnm67Δ cells exhibited an ∼10-min delay in regenerating the G1 population (Fig. 3A). Under the same conditions, provision of a multicopy CDC5 plasmid into the cnm67Δ mutant completely abolished this delay (Fig. 3A). Consistent with the restoration of the cell cycle delay, provision of a centromeric CDC5 partially suppressed the cnm67Δ-associated growth defect, whereas provision of a multicopy CDC5 almost fully suppressed the cnm67Δ defect (Fig. 3B). These observations suggest that cnm67Δ is impaired in the Cdc5p-dependent mitotic functions, because of the delocalization of Cdc5p from the SPB.

One of the critical functions of Cdc5p during M-phase progression is to promote mitotic exit. Thus, if a failure in mitotic exit is the only critical defect associated with the delocalized Cdc5p in cnm67Δ, then bypass of mitotic exit should alleviate the growth defect associated with the cnm67Δ mutation. However, introduction of either a dominant CDC14 allele, CDC14TAB6-1, which bypasses the requirement for CDC15 and TEM1 function in mitotic exit (45), or bfa1Δ, which suppresses the mitotic exit defect of the temperature-sensitive cdc5-1 mutation (39), failed to suppress the cnm67Δ defect under various conditions (data not shown). These observations suggest that cnm67Δ is defective in multiple mitotic processes that can be suppressed by the overexpression of CDC5.

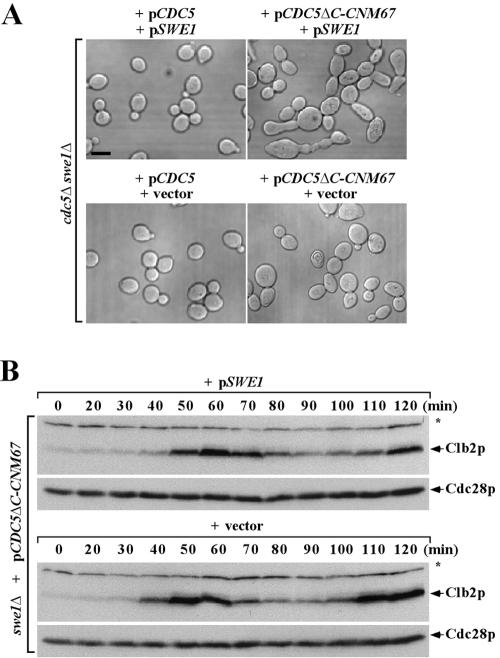

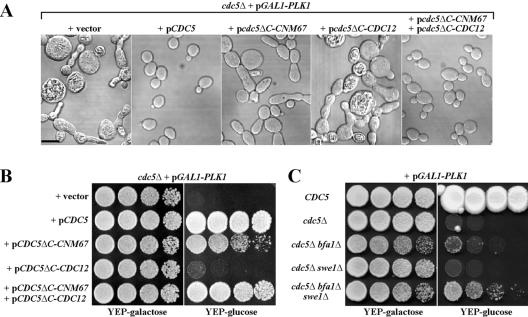

The CDC5ΔC-CNM67 allele is defective in the Swe1p pathway.

To investigate the localization-dependent mitotic functions of Cdc5p, we closely examined several viable CDC5ΔC mutants (CDC5ΔC-CNM67, CDC5ΔC-SPC42, and CDC5ΔC-SPC98) to determine the defect(s) associated with the lack of the neck-localized Cdc5p activity. All three mutants, which express each Cdc5pΔC-fused chimera as the sole source of Cdc5p under endogenous CDC5 promoter control, exhibited an elongated bud morphology (Fig. 4A and data not shown). Since this phenotype is observed in mutants in which Swe1p downregulation is defective (29, 46), we introduced swe1Δ into these mutants. The CDC5ΔC-CNM67 swe1Δ double mutant (KLY4522) grew with a wild-type morphology (data not shown). Conversely, provision of SWE1 on a CEN plasmid into the CDC5ΔC-CNM67 swe1Δ cells (KLY4522) reimposed this morphological defect (Fig. 4A). Similarly, introduction of swe1Δ into the slow-growing CDC5ΔC-SPC42 or CDC5ΔC-SPC98 mutant greatly diminished, but did not abolish, the elongated morphology (data not shown), a finding suggestive of additional undetermined defect(s) in these mutants. Collectively, these results suggest that the lack of Cdc5p localization to the bud-neck results in a defect in the SWE1 regulatory pathway. Consistent with this notion, the CDC5ΔC-CNM67 swe1Δ mutant bearing a centromeric SWE1 plasmid exhibited an ∼10-min delay in achieving the maximum level of Clb2p after release from the α-factor block (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Tethering the Cdc5pΔC to the SPB leads to a defect in the SWE1 pathway. (A) Strain KLY4522 (cdc5Δ swe1Δ) was doubly transformed with either pCDC5 or pCDC5ΔC-CNM67 in combination with pSWE1 or the corresponding vector. Obtained transformants were cultured overnight and fixed for microscopic examination. Bar, 5 μm. (B) CDC5ΔC-CNM67 exhibits a SWE1-dependent cell cycle delay. Strain KLY4753 (CDC5ΔC-CNM67 swe1Δ) harboring either an integrated copy of wild-type SWE1 (KLY4793) or the corresponding vector (KLY4795) were arrested in G1 by α-factor treatment for 2 h and then released. At the indicated times, samples were taken to prepare total cellular proteins. Proteins were separated by SDS-10% PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against Clb2p or Cdc28p. The levels of Cdc28p served as loading controls. Asterisks indicate a cross-reacting protein with anti-Clb2 antibody.

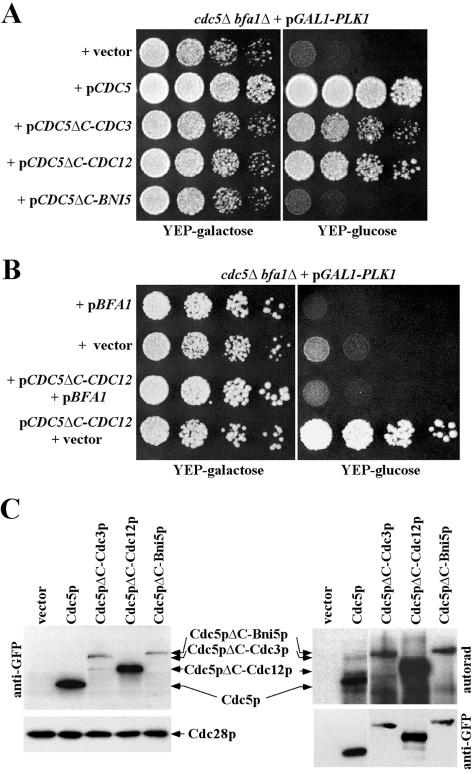

Rescue of the Cdc5pΔC-neck defect by bfa1Δ.

Since many components functioning in the MEN localize to the SPB, we reasoned that the inability of the CDC5ΔC-neck chimera to complement the cdc5Δ defect could be due to a failure in exiting from mitosis. To investigate this possibility, we examined the ability of the CDC5ΔC-neck chimera to complement the cdc5Δ defect in the absence of BFA1, a negative regulator of the Tem1p-dependent MEN. To this end, a cdc5Δ bfa1Δ double mutant kept viable by the expression of GAL1-PLK1 (KLY4641) was transformed with a centromeric CDC5, CDC5ΔC-CDC3, CDC5ΔC-CDC12, or CDC5ΔC-BNI5 (CDC5ΔC-CDC10 and CDC5ΔC-CDC11 were excluded from this analysis because of the less distinct localization to the bud-neck [see Fig. 1B]). The viability of the resulting transformants was then examined after repressing PLK1 expression. Introduction of a centromeric CDC5 plasmid fully rescued the lethality of cdc5Δ bfa1Δ, whereas vector did not (Fig. 5A). Under the same conditions, provision of either CDC5ΔC-CDC3 or CDC5ΔC-CDC12, but not CDC5ΔC-BNI5, rescued the lethality of cdc5Δ bfa1Δ efficiently (Fig. 5A). Conversely, provision of both BFA1 and CDC5ΔC-CDC12 into strain KLY4641 (cdc5Δ bfa1Δ + pGAL1-PLK1) failed to rescue the cdc5Δ bfa1Δ double mutant (Fig. 5B). These observations indicate that the inability of CDC5ΔC-CDC3 or CDC5ΔC-CDC12 to rescue the cdc5Δ defect is because of its inability to mediate mitotic exit.

FIG. 5.

Rescue of the lethality of CDC5ΔC-neck chimera by bfa1Δ. (A) Strain KLY4641 (cdc5Δ bfa1Δ + pGAL1-PLK1) transformed with the indicated plasmids was cultured overnight, serially diluted, and then spotted onto either YEP-galactose or YEP-glucose plates at 30°C. (B) To confirm the bfa1Δ-dependent rescue of the cdc5Δ lethality by CDC5ΔC-CDC12, strain KLY4641 (cdc5Δ bfa1Δ + pGAL1-PLK1) was transformed with either a centromeric BFA1 plasmid or a control vector or doubly transformed with pCDC5ΔC-CDC12 in combination with pBFA1 or the control vector. The obtained transformants were cultured overnight and spotted as described in panel A. (C) To examine the protein expression levels and kinase activities of the indicated chimera proteins, strain JB811 was transformed with the indicated constructs. Total cellular proteins were subjected to immunoblotting (left panel) with antibodies to GFP or Cdc28p (loading control). Immunocomplex kinase assays (right panel) were carried out with anti-Flag antibody. Both the autophosphorylation activities (upper panel) and the levels of immunoprecipitated proteins (lower panel) are shown.

In contrast to CDC5ΔC-CDC12 or CDC5ΔC-CDC3, CDC5ΔC-BNI5 failed to rescue the cdc5Δ bfa1Δ growth defect (Fig. 5A). Immunoblotting and immunocomplex kinase assays revealed that both the protein expression level and the kinase activity of Cdc5pΔC-Bni5p were similar to those of Cdc5pΔC-Cdc3p, although Cdc5pΔC-Cdc12p was expressed at a severalfold-higher level (Fig. 5C). These observations suggest that septins such as Cdc12p or Cdc3p, but not Bni5p, can target the catalytic activity of Cdc5pΔC to a specific location at the bud-neck, permitting close proximity of Cdc5p to physiological substrates critical for mitotic events at this site.

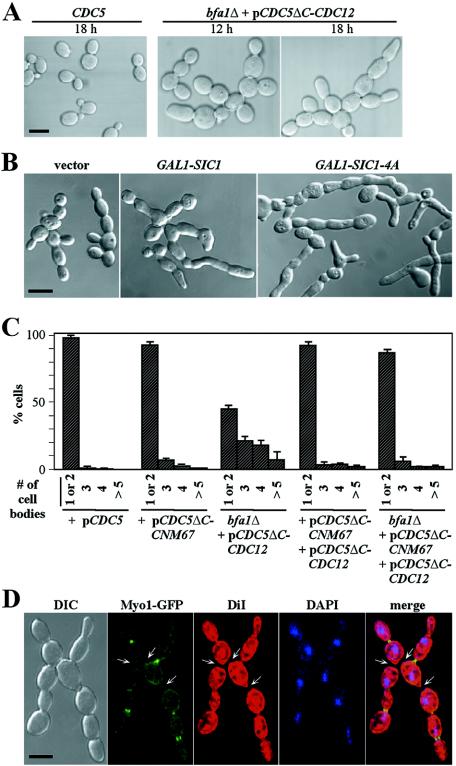

Defects of CDC5ΔC-CDC12 bfa1Δ in both membrane closure and septum formation.

To investigate additional defect(s) associated with the lack of Cdc5p localization to the SPB, strain KLY4798 (cdc5Δ bfa1Δ YFP-CDC10 + pCDC5ΔC-CDC12 + pGAL1-PLK1), in which mitotic exit failure is bypassed by bfa1Δ, was closely examined after the depletion of Plk1p. Strain KLY4787 (cdc5Δ YFP-CDC10 + pCDC5 + pGAL1-PLK1) harboring a CDC5 wild-type was also examined for comparison. Upon transferring the cultures to 1% yeast extract-2% Bacto Peptone-glucose medium to repress the PLK1 expression, strain KLY4798 induced a chained cell morphology in a time-dependent manner, whereas strain KLY4787 did not (Fig. 6A). CDC5ΔC-CDC3 bfa1Δ also exhibited a similar level of chained cells (data not shown). Since a delay in the inactivation of Cdc28/Clb causes a cytokinetic defect (51), we examined whether expression of a Cdc28p inhibitor, SIC1 or its activated phosphosite mutant SIC1-4A (53), influences the level of the chained cell morphology. As expected, expression of these constructs inhibited Cdc28p kinase activity (see Fig. 6G) and induced an elongated morphology but failed to diminish the level of chained cell morphologies (Fig. 6B), suggesting that the observed cytokinetic defect in CDC5ΔC-CDC12 bfa1Δ is not the result of a delayed downregulation of Cdc28p/Clb activity.

FIG. 6.

CDC5ΔC-CNM67, but not CDC5ΔC-CDC12, is competent for the function of CDC5 in cytokinesis. (A) Strains KLY4787 (CDC5) and KLY4798 (cdc5Δ bfa1Δ + pCDC5ΔC-CDC12) were cultured in YEP-galactose overnight and then shifted to YEP-glucose to repress PLK1 expression. At the indicated time point, cells were harvested, fixed, and subjected to microscopic analyses. Representative morphologies are shown. Bar, 5 μm. (B) Strain KLY5419 (cdc5Δ bfa1Δ + pCDC5ΔC-CDC12; 5-fluoroorotic acid-resistant cells of KLY4798) was integrated with control vector, GAL1-SIC1, or GAL1-SIC1-4A. The resulting transformants (strains KLY5423, KLY5424, and KLY5425, respectively) were cultured in YEP-raffinose overnight and then shifted to YEP-galactose for 5 h prior to microscopic examination. Likely as a result of Cdc28p inhibition, cells expressing GAL1-SIC1 or GAL1-SIC1-4A exhibit an elongated morphology. Bar, 5 μm. (C) Indicated strains were cultured at 30°C in YEP-galactose overnight and then shifted to YEP-glucose for 24 h to deplete Plk1p. Cells were harvested and treated with zymolyase to remove the cell wall and then the percentage of connected cells were quantified. (D) Strain KLY5370, which expresses MYO1-GFP under endogenous MYO1 promoter control, was cultured in YEP-glucose, fixed, and then stained with DiI or DAPI to reveal membrane or DNA morphologies, respectively. Arrows indicate detached membranes after cytokinesis. Bar, 5 μm. (E) Strain KLY1083 (GAL1-CDC5ΔN) transformed with the indicated plasmids was cultured at 30°C in YEP-glucose overnight. Cultures were then shifted to YEP-galactose for 12 h to induce the CDC5ΔN-dependent cytokinetic defects. Samples were fixed, and the cells with connected morphologies were quantified. Error bars indicate the standard deviations. (F and G) Strain KLY4816 (CDC5-GFP) was integrated with control vector, GAL1-SIC1, or GAL1-SIC1-4A. The resulting transformants (KLY5372, KLY5373, or KLY5374, respectively) were cultured in YEP-raffinose overnight, treated with nocodazole for 2 h to arrest them in prometaphase, and then shifted to YEP-galactose supplemented with nocodazole to express the GAL1-promoter driven SIC1 or SIC1-4A. Samples were taken at the indicated times to determine the Cdc5p-GFP localization to the bud-neck (F) and the Cdc28 activity by using histone H1 as the substrate (G). H1, phosphorylated histone H1; Cdc28p, p13suc1-precipitated Cdc28p.

To determine whether the chained cell morphology is the result of a defect in membrane closure, cells were treated with zymolyase, and then cell bodies with connected cytoplasm were counted. The cdc5Δ cells expressing either CDC5ΔC-CNM67 (KLY4789) or both CDC5ΔC-CNM67 and CDC5ΔC-CDC12 (KLY5012) did not exhibit significant chained cell morphologies (data not shown) or connected cell bodies after zymolyase treatment (Fig. 6C). In contrast, CDC5ΔC-CDC12 bfa1Δ cells (KLY4798) exhibited the connected cell bodies in 53% of the population (Fig. 6C), indicating a defect in membrane closure. A similar level of defect was also observed with CDC5ΔC-CDC3 bfa1Δ cells (59% connected cell bodies [n = 196]). bfa1Δ did not appear to contribute to this cytokinetic defect, since bfa1Δ cells containing both pCDC5ΔC-CNM67 and pCDC5ΔC-CDC12 did not exhibit this defect (Fig. 6C).

To examine whether the lack of the SPB-associated Cdc5p activity also influences septum formation, asynchronously growing CDC5ΔC-CDC12 bfa1Δ cells bearing Myo1-GFP (KLY5370) were fixed, sonicated to separate adherent cells (but no zymolyase treatment to preserve cell wall), and then stained with DiI to reveal the membrane morphologies. Among the chained cell bodies (excluding the bud-generating necks at the periphery of chained cells), ca. 62% (n = 82) exhibited connected cytoplasms, whereas the remaining 38% exhibited detached membranes with no detectable Myo1p-GFP signals between them (Fig. 6D). These observations suggest that CDC5ΔC-CDC12 bfa1Δ cells are also significantly delayed in septum formation after membrane closure. In support of this notion, time-lapse microscopic analyses revealed that, in comparison to the isogenic wild-type where the septum formation occurs within 10 to 15 min after membrane closure, CDC5ΔC-CDC12 bfa1Δ cells required a substantially longer time for both membrane closure (as indicated by the slow contraction of Myo1p-GFP ring) and subsequent septum formation (as judged by the sustained connected-cell morphology even after disappearance of Myo1p-GFP signal) (see Fig. S2 at http://home.ccr.cancer.gov/metabolism/klee/mcb_vol24_No22_supplementary).

Importance of the SPB-, but not the bud-neck-, associated Cdc5p in regulating cytokinesis.

To confirm the importance of the SPB-associated Cdc5p activity for normal cytokinesis, we compared the ability of Cdc5pΔC-Cnm67p and Cdc5pΔC-Cdc12p (the two most functional SPB or bud-neck chimera proteins, based on their ability to complement the cdc5Δ lethality) to remedy the cytokinetic defect induced by impaired CDC5 function. As previously reported (49), overexpression of a dominant-negative CDC5ΔN in an otherwise wild-type genetic background induced a cytokinesis defect with a severe chained cell morphology. Introduction of a centromeric CDC5ΔC-CNM67, but not CDC5ΔC-CDC12, plasmid greatly diminished the CDC5ΔN-induced chained cell morphology (Fig. 6E). In addition, CDC5ΔC-CNM67, but not CDC5ΔC-CDC12, suppressed the cytokinetically defective cdc5-7 CDC14TAB6-1 mutant (36) efficiently (data not shown). These data suggest that the SPB-localized Cdc5 activity, but not the bud neck-associated activity, is important for the function of Cdc5p in cytokinesis.

The importance of the SPB-localized Cdc5p in regulating cytokinesis is surprising because Dbf2p, which also functions in the MEN, translocates to the bud-neck as a consequence of Cdc28p/Clb downregulation and this event correlates with septum formation (26). To investigate whether Cdc28p/Clb activity also regulates Cdc5p localization to the bud-neck, we examined whether the expression of GAL1-SIC1 or GAL1-SIC1-4A influences the localization of an endogenous promoter-controlled Cdc5p-GFP in nocodazole-arrested cells. Probably because of a low level of expression, only a small fraction (ca. 7%) of asynchronously growing cells exhibited bud-neck localized Cdc5p-GFP signals. Unlike Dbf2p, however, Cdc5p was already localized to the bud-neck in cells arrested with nocodazole (Fig. 6F). In addition, expression of GAL1-SIC1 or GAL1-SIC1-4A failed to increase the population bearing the neck-localized Cdc5p-GFP (Fig. 6F) or to enhance the intensity of the Cdc5p-GFP signals at this site (data not shown), even though the Cdc28p activity became significantly diminished under the same conditions (Fig. 6G). These data indicate that, unlike Dbf2p, the downregulation of Cdc28p/Clb activity is not required for the localization of Cdc5p-GFP to the bud-neck.

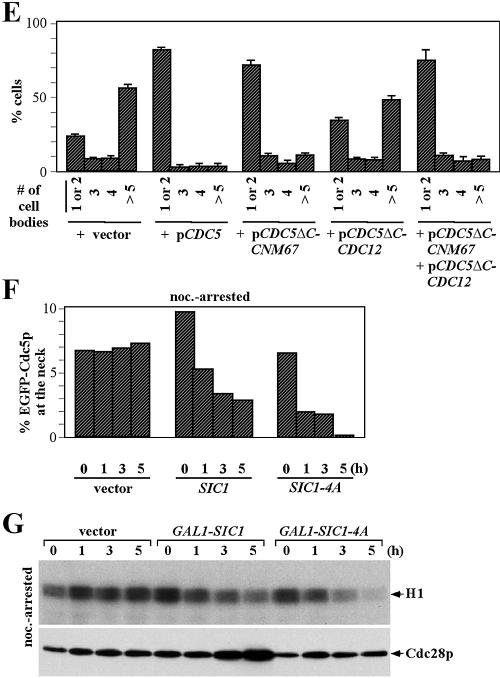

Reconstitution of Cdc5p function by Cdc5pΔC-Cnm67p and Cdc5pΔC-Cdc12p.

We then examined whether the provision of both the SPB-localizing Cdc5pΔC-Cnm67p and the bud-neck-localizing Cdc5pΔC-Cdc12p can restore the cdc5Δ defect. Upon depletion of Plk1p, cdc5Δ cells bearing a centromeric CDC5ΔC-CNM67 (KLY4626) plasmid exhibited an elongated morphology, whereas cdc5Δ cells bearing CDC5ΔC-CDC12 (KLY4656) failed to grow and exhibited a severely swollen morphology (Fig. 7A). Under the same conditions, strain KLY4628 bearing both CDC5ΔC-CNM67 and CDC5ΔC-CDC12 plasmids exhibited a cell morphology similar to that of strain KLY4486 harboring the wild-type CDC5 (Fig. 7A) and grew well (Fig. 7B), although it exhibited a mild mitotic delay (data not shown). These observations suggest that both the SPB- and the bud-neck-localized Cdc5p activities regulate most of the critical Cdc5p functions required for mitotic progression.

FIG. 7.

Reconstitution of Cdc5p activity by Cdc5pΔC-Cnm67p and Cdc5pΔC-Cdc12p. (A) The indicated strains were cultured in YEP-galactose overnight and then shifted to YEP-glucose to deplete Plk1p. At the 24-h time point, cells were harvested, fixed, and subjected to microscopic analyses. Bar, 5 μm. (B) The same strains as in panel A were cultured overnight, serially diluted, and then spotted onto either YEP-galactose or YEP-glucose plates at 30°C. (C) To examine the ability of bfa1Δ and swe1Δ to suppress the cdc5Δ defect, the indicated strains, which were maintained by the expression of GAL1-PLK1, were cultures and spotted as in panel B.

Since CDC5ΔC-CNM67 and CDC5ΔC-CDC12 are defective in Swe1p regulation and Bfa1p-dependent mitotic exit, respectively, we next sought to determine whether introduction of both swe1Δ and bfa1Δ alleviates the cdc5Δ lethality. Loss of either SWE1 or BFA1 alone did not suppress the cdc5Δ lethality, even though small nonviable microcolonies were visible in the cdc5Δ bfa1Δ mutant (Fig. 7C). Interestingly, loss of both SWE1 and BFA1 yielded viable progenies, but this cdc5Δ bfa1Δ swe1Δ triple mutant grew very poorly (Fig. 7C). These data suggest that downregulation of both Swe1p- and Bfa1p-dependent pathways are two critical events that require Cdc5p, although they are unlikely to be the only Cdc5p-dependent events at these two subcellular locations (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Subcellular localizations and mitotic functions of Cdc5p at each location (see the text for details).

DISCUSSION

Multiplicity of Cdc5p localization to the SPB.

To provide new insights into the localization-dependent mitotic functions of Cdc5p, we examined whether the localization-defective, nonfunctional, Cdc5pΔC can form a functional fusion with various components at the SPB or the bud-neck. We reasoned that only the chimeras that could target the catalytic activity of Cdc5p (Cdc5pΔC) to the region within the SPB or bud-neck where endogenous Cdc5p normally localize would bring Cdc5pΔC in proximity with its substrates critical for mitotic functions at these subcellular locations. Among the SPB components, Cnm67p, which localizes between central and outer plaques (41), targeted Cdc5pΔC to the SPB and rescued the cdc5Δ lethality well. In addition, the Cdc5pΔC fusions generated with Spc42p, a central plaque component interacting with Cnm67p (14), or two outer plaque components, Spc98p and Spc97p, rescued the cdc5Δ defect relatively well. These observations suggest that Cdc5p activity critical for supporting cell viability is in proximity to these components at the central to outer plaque of the SPB.

We have shown that Cdc5p localization to the SPB is impaired, but not completely disrupted, in the bbp1-1 mutant (35), suggesting that Bbp1p is important but not solely responsible for Cdc5p localization to the SPB. Here we showed that localization of Cdc5p-GFP to the SPB in cnm67Δ was severely impaired, although not eliminated, at 37°C and overexpression of CDC5 suppressed both the cell cycle delay and the growth defect of cnm67Δ at 37°C. These observations suggest that, in addition to Bbp1p, SPB component(s) or structure(s) that requires Cnm67p at an elevated temperature are also important for proper localization of Cdc5p. However, close examination of Cdc5p localization in various central and outer plaque SPB mutants failed to identify a single component critical for Cdc5p localization. Given the multiple mitotic events that Cdc5p regulates, it is possible that Cdc5p interacts with multiple, perhaps both Cnm67p-independent (i.e., Bbp1p) and -dependent, components at the SPB. Interestingly, Cdc5p strongly interacted with Nud1p and also weakly with several other SPB components including Bbp1p. These data suggest that Nud1p might be one of the Cnm67p-dependent Cdc5p-interacting proteins at the SPB. However, this interaction is probably transient in vivo, since immunoprecipitation of Cdc5p failed to coprecipitate Nud1p or any other SPB components under various conditions (data not shown). It has been shown that Nud1p plays an important role in mitotic exit and cytoplasmic microtubule organization and coimmunoprecipitates components in the MEN, such as Bfa1p and Bub2p (18). Thus, the interaction between Cdc5p and Nud1p may be important in linking Cdc5p with the MEN components at the SPB. In support of this view, overexpression of CDC5 suppresses the growth defect associated with nud1-44 or nud1-52 mutation (see Fig. S3 at http://home.ccr.cancer.gov/metabolism/klee/mcb_vol24_No22_supplementary). However, it is not clear why CDC5ΔC-NUD1, which localized to the SPB and was catalytically active, was not able to suppress the cdc5Δ growth defect. It is possible that, unlike other chimera mutants, CDC5ΔC-NUD1 may have an uncharacterized defect critical for Cdc5p function.

The bud-neck localized Cdc5p is critical for proper Swe1p regulation.

Our data showed that bfa1Δ suppressed the growth defect associated with two septin-fused chimeras, CDC5ΔC-CDC3 and CDC5ΔC-CDC12, in a cdc5Δ background. However, bfa1Δ failed to suppress the cdc5Δ growth defect. These data indicate that CDC5ΔC-CDC3 or CDC5ΔC-CDC12 activity is required for bfa1Δ to suppress the cdc5Δ defect. Interestingly, CDC5ΔC-BNI5 failed to support the cdc5Δ defect in the same bfa1Δ background, suggesting that Bni5p is unable to target Cdc5pΔC to its native location at the bud-neck. In line with these observations, Cdc5p interacts with two of the septins, Cdc11p and Cdc12p (49), but not with Bni5p (data not shown), in a yeast two-hybrid assay and coimmunoprecipitates Cdc11p in a polo-box-dependent manner (49). Taken together, these observations suggest that the bud-neck-localized Cdc5p activity, perhaps through the interaction with septins, is required to fulfill critical Cdc5p functions at the bud-neck.

Studies with CDC5ΔC-CNM67 revealed that lack of Cdc5p localization to the bud-neck leads to a delay in G2/M transition, which is abolished by the introduction of swe1Δ. In addition, provision of the neck-localizing CDC5ΔC-CDC12 rescued the elongated bud morphology associated with CDC5ΔC-CNM67. These data suggest that the neck-localized Cdc5p is required for proper Swe1p regulation. In support of this view, Swe1p was hypophosphorylated and stabilized in the absence of the bud-neck associated Cdc5p (40), suggesting the importance of the neck-localized Cdc5p in the downregulation of Swe1p. However, it is interesting that CDC5ΔC-CDC12 bfa1Δ cells grow relatively well, whereas cdc5Δ bfa1Δ swe1Δ cells grow very poorly. These observations suggest that downregulation of Swe1p is not likely to be the only event that requires the Cdc5 function at the neck.

Cdc5p localizes to the SPB to promote mitotic exit and cytokinesis.

Our results showed that lack of Cdc5p localization to the SPB leads to a failure in mitotic exit, and this defect appears to be the primary cause of the CDC5ΔC-CDC3 or CDC5ΔC-CDC12 lethality. Conversely, CDC5ΔC-CNM67 appeared to be proficient for mitotic exit, further suggesting the importance of the SPB-localized Cdc5p in regulating mitotic exit. However, CDC5ΔC-CNM67 cells grow well, whereas cdc5Δ bfa1Δ cells do not. These results suggest that, in addition to mitotic exit, the SPB-localized Cdc5p is required for additional uncharacterized mitotic event(s).

Close examination of the viable CDC5ΔC-CDC3 bfa1Δ or CDC5ΔC-CDC12 bfa1Δ double mutants revealed that these cells are severely delayed in both membrane closure and septum formations, suggesting that the SPB-localized Cdc5p population is required for proper cytokinesis. It is possible that the fusions of Cdc5pΔC with Cdc3p or Cdc12p may have altered the capacity of Cdc5p to interact with cytokinetically important proteins at the bud-neck, thus resulting in these defects. However, we proposed that the lack of the SPB-localized Cdc5p is likely the cause of the cytokinetic defect associated with the CDC5ΔC-CDC3 bfa1Δ or CDC5ΔC-CDC12 bfa1Δ mutant, since the SPB-localizing CDC5ΔC-CNM67 mutant did not exhibit any significant level of cytokinetic defect. In further support of this notion, the SPB-localized, but not the bud-neck-associated, Cdc5p activity efficiently rescued the dominant-negative CDC5ΔN-dependent cytokinetic defect.

The importance of the SPB-associated Cdc5p in regulating cytokinesis contrasts with a recent report (26) that suggested that relocalization of Dbf2p from the SPB to the bud-neck, which is triggered by the downregulation of mitotic Cdc28p activity, is required for septum formation. In addition, even though both Cdc5p and Dbf2p functions in the MEN, Cdc5p exhibits several properties distinct from those of Dbf2p. First, unlike Dbf2p, Cdc5p already localized to the bud-neck in nocodazole-treated prometaphase cells, the stage where Cdc28p is maximally active. Second, overexpression of the Cdc28p inhibitor SIC1 did not enhance the level of Cdc5p localization to the bud-neck. Third, CDC5ΔC-CDC3 or CDC5ΔC-CDC12 cells exhibited cytokinetic defects in the absence of the MEN negative regulator BFA1, suggesting that these defects are MEN independent. Thus, these data strongly suggest that Cdc5p contributes to the cytokinesis both through the MEN-independent and MEN-dependent pathways.

Studies in mammalian cells demonstrated that Plk1p localization to the spindle midzone is important for ingression of the cleavage furrow (33). In fission yeast, Plo1p localizes to mitotic spindles and the medial ring and play an important role in medial ring organization and septum formation (5, 32, 34). Unlike these organisms, Cdc5p localization to the mitotic spindles or midzone has not been reported in budding yeast. Instead, Cdc5p localizes to the cytokinetically important bud-neck filament, suggesting that the neck-localized Cdc5p may be responsible for the role of Cdc5p in cytokinesis. However, our data show that the SPB-associated Cdc5p is critical for cytokinesis and that CDC5ΔC-CNM67, which has no detectable level of bud-neck localization, appears to support cell division well without yielding a significant level of chained cell morphology. Furthermore, relocalization of Cdc5p from the SPB to the bud-neck is not a requirement for contributing to cytokinesis, suggesting that budding yeast utilizes distinct mechanism(s) to relay polo kinase-mediated cytokinetic signals from the SPB. Since the future cleavage plane in budding yeast is defined early in the cell cycle by forming septin ring structures at the bud-neck, the differences in molecular events of regulating cytokinesis may reflect the differences in the temporal and spatial arrangement of cytokinetic events in these evolutionarily distinct eukaryotic cells.

Additional Cdc5p functions.

Mitotic events are highly orchestrated cellular and biochemical processes that ensure proper segregation of both nuclear and cytosolic materials into two dividing cells. Both temporal and spatial regulation of Cdc5p is important to coordinate the stage-specific mitotic events that it regulates. We showed that the SPB-associated Cdc5p activity is critical for mitotic exit and cytokinesis, whereas the bud-neck-localized Cdc5p activity is important for Swe1p regulation. However, neither CDC5Δ-CNM67 swe1Δ nor CDC5ΔC-CDC12 bfa1Δ grow as well as the isogenic wild-type, even though CDC5Δ-CNM67 and CDC5ΔC-CDC12 appear to provide sufficient Cdc5p activity to downregulate Bfa1p- and Swe1p-dependent pathways, respectively. These observations suggest that, in addition to regulating Bfa1p and Swe1p, Cdc5p regulates other molecular events critical for normal cell cycle progression. It has been shown that Cdc5p phosphorylates a cohesin subunit Scc1p and enhances its cleavage, a step essential for sister chromatid separation (3). In support of this observation, both CDC5ΔC-CNM67 (KLY5209) and CDC5-CDC12 bfa1Δ (KLY5246) cells exhibited greatly diminished Scc1p phosphorylation (prominent in nocodazole-arrested condition) and significantly reduced Scc1p cleavage (See Fig. S4 at http://home.ccr.cancer.gov/metabolism/klee/mcb_vol24_No22_supplementary), suggesting that inefficient Scc1p cleavage may have contributed to the slow cell growth of these mutants. Interestingly, cdc5Δ cells bearing both CDC5ΔC-CNM67 and CDC5ΔC-CDC12 grow relatively well, whereas cdc5Δ bfa1Δ swe1Δ cells grow very poorly. Overexpression of ESP1, which is essential for the dissociation of Scc1p from sister chromatids (11), or provision of a dominant CDC14TAB6-1 allele (45) failed to suppress the cdc5Δ bfa1Δ swe1Δ growth defect (data not shown). These observations suggest that cdc5Δ bfa1Δ swe1Δ cells lack other critical Cdc5p function(s) from the SPB and/or the bud-neck and these defect(s) are accountable for poor cell growth. Isolation of additional components that alleviate the cdc5Δ bfa1Δ swe1Δ defect may lead to a better understanding of other mitotic events that require the function of Cdc5p.

Acknowledgments

We thank Craig Bennett, Trisha Davis, Raymond J. Deshaies, John Kilmartin, Daniel J. Lew, David O. Morgan, Elmar Schiebel, and Mark Winey for reagents; Susan Garfield for help with confocal microscopy; and Tara Millington for reading the manuscript. We also thank Chris Spates for support throughout the course of this work.

This study was supported, in part, by an NIH Office of International Affairs predoctoral fellowship (J.-E.P.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, I. R., and J. V. Kilmartin. 1999. Localization of core spindle pole body (SPB) components during SPB duplication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 145:809-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams, I. R., and J. V. Kilmartin. 2000. Spindle pole body duplication: a model for centrosome duplication? Trends Cell Biol. 10:329-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexandru, G., F. Uhlmann, K. Mechtler, M. A. Poupart, and K. Nasmyth. 2001. Phosphorylation of the cohesin subunit Scc1 by polo/Cdc5 kinase regulates sister chromatid separation in yeast. Cell 105:459-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1995. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., New York, N.Y.

- 5.Bahler, J., A. B. Steever, S. Wheatley, Y. I. Wang, J. R. Pringle, K. L. Gould, and D. McCollum. 1998. Role of polo kinase and Mid1p in determining the site of cell division in fission yeast. J. Cell Biol. 143:1603-1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barral, Y., M. Parra, S. Bidlingmaier, and M. Snyder. 1999. Nim1-related kinases coordinate cell-cycle progression with the organization of the peripheral cytoskeleton in yeast. Genes Dev. 13:176-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartholomew, C. R., S. H. Woo, Y. S. Chung, C. Jones, and C. F. Hardy. 2001. Cdc5 interacts with the Wee1 kinase in budding yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:49-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boeke, J. D., F. L. Croute, and G. R. Fink. 1984. A positive selection for mutants lacking orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase activity in yeast: 5-fluoroorotic acid resistance. Mol. Gen. Genet. 197:345-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Booher, R. N., R. J. Deshaies, and M. W. Kirschner. 1993. Properties of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae wee1 and its differential regulation of p34cdc28 in response to G1 and G2 cyclins. EMBO J. 12:3417-3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, X. P., H. Yin, and T. C. Huffaker. 1998. The yeast spindle pole body component Spc72p interacts with Stu2p and is required for proper microtubule assembly. J. Cell Biol. 141:1169-1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciosk, R., W. Zachariae, C. Michaelis, A. Shevchenko, M. Mann, and K. Nasmyth. 1998. An ESP1/PDS1 complex regulates loss of sister chromatid cohesion at the metaphase to anaphase transition in yeast. Cell 93:1067-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clyne, R. K., V. L. Katis, L. Jessop, K. R. Benjamin, I. Herskowitz, M. Lichten, and K. Nasmyth. 2003. Polo-like kinase Cdc5 promotes chiasmata formation and cosegregation of sister centromeres at meiosis I. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:480-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edgington, N. P., M. J. Blacketer, T. A. Bierwagen, and A. M. Myers. 1999. Control of Saccharomyces cerevisiae filamentous growth by cyclin-dependent kinase Cdc28. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:1369-1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elliott, S., M. Knop, G. Schlenstedt, and E. Schiebel. 1999. Spc29p is a component of the Spc110p subcomplex and is essential for spindle pole body duplication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:6205-6210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geymonat, M., A. Spanos, S. J. Smith, E. Wheatley, K. Rittinger, L. H. Johnston, and S. G. Sedgwick. 2002. Control of mitotic exit in budding yeast: in vitro regulation of Tem1 GTPase by Bub2 and Bfa1. J. Biol. Chem. 277:28439-28445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geymonat, M., A. Spanos, P. A. Walker, L. H. Johnston, and S. G. Sedgwick. 2003. In vitro regulation of budding yeast Bfa1/Bub2 GAP activity by Cdc5. J. Biol. Chem. 278:14591-14594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gladfelter, A. S., J. R. Pringle, and D. J. Lew. 2001. The septin cortex at the yeast mother-bud neck. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:681-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gruneberg, U., K. Campbell, C. Simpson, J. Grindlay, and E. Schiebel. 2000. Nud1p links astral microtubule organization and the control of exit from mitosis. EMBO J. 19:6475-6488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu, F., Y. Wang, D. Liu, Y. Li, J. Qin, and S. J. Elledge. 2001. Regulation of the Bub2/Bfa1 GAP complex by Cdc5 and cell cycle checkpoints. Cell 107:655-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jang, Y. J., C. Y. Lin, S. Ma, and R. L. Erikson. 2002. Functional studies on the role of the C-terminal domain of mammalian polo-like kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:1984-1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitada, K., A. L. Johnson, L. H. Johnston, and A. Sugino. 1993. A multicopy suppressor gene of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae G1 cell cycle mutant gene dbf4 encodes a protein kinase and is identified as CDC5. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:4445-4457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, B. H., and A. Amon. 2003. Role of polo-like kinase CDC5 in programming meiosis I chromosome segregation. Science 300:482-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, K. S., and R. L. Erikson. 1997. Plk is a functional homolog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cdc5, and elevated Plk activity induces multiple septation structures. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:3408-3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, P. R., S. Song, H. S. Ro, C. J. Park, J. Lippincott, R. Li, J. R. Pringle, C. D. Virgilio, M. S. Longtine, and K. S. Lee. 2002. Bni5p, a septin-interacting protein, is required for normal septin function and cytokinesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:6906-6920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lew, D. J., and S. I. Reed. 1993. Morphogenesis in the yeast cell cycle: regulation by Cdc28 and the cyclins. J. Cell Biol. 120:1305-1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim, H. H., F. M. Yeong, and U. Surana. 2003. Inactivation of mitotic kinase triggers translocation of MEN components to mother-daughter neck in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:4734-4743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lippincott, M., and R. Li. 1998. Dual function of Cyk2, a cdc15/PSTPIP family protein, in regulating actomyosin ring dynamics and septin distribution. J. Cell Biol. 143:1947-1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma, X.-J., Q. Lu, and M. Grunstein. 1996. A search for proteins that interact genetically with histone H3 and H4 amino termini uncovers novel regulators of the Swe1 kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 10:1327-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McMillan, J. N., M. S. Longtine, R. A. Sia, C. L. Theesfeld, E. S. Bardes, J. R. Pringle, and D. J. Lew. 1999. The morphogenesis checkpoint in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: cell cycle control of Swe1p degradation by Hsl1p and Hsl7p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:6929-6939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McMillan, J. N., C. L. Theesfeld, J. C. Harrison, E. S. Bardes, and D. J. Lew. 2002. Determinants of Swe1p degradation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:3560-3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulvihill, D. P., J. Petersen, H. Ohkura, D. M. Glover, and I. M. Hagan. 1999. Plo1 kinase recruitment to the spindle pole body and its role in cell division in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Biol. Cell 10:2771-2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neef, R., C. Preisinger, J. Sutcliffe, R. K. R., E. A. Nigg, T. U. Mayer, and F. A. Barr. 2003. Phosphorylation of mitotic kinesin-like protein 2 by polo-like kinase 1 is required for cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 162:863-875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohkura, H., I. M. Hagan, and D. M. Glover. 1995. The conserved Schizosaccharomyces pombe kinase plo1, required to form a bipolar spindle, the actin ring, and septum, can drive septum formation in G1 and G2 cells. Genes Dev. 9:1059-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park, C. J., S. Song, T. H. Giddings, Jr., H. S. Ro, K. Sakchaisri, J. E. Park, Y. S. Seong, M. Winey, and K. S. Lee. 2004. Requirement for Bbp1p in the proper mitotic functions of Cdc5p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:1711-1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park, C. J., S. Song, P. R. Lee, W. Shou, R. J. Deshaies, and K. S. Lee. 2003. Loss of CDC5 function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae leads to defects in Swe1p regulation and Bfa1p/Bub2p-independent cytokinesis. Genetics 163:21-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pereira, G., T. Hofken, J. Grindlay, C. Manson, and E. Schiebel. 2000. The Bub2 spindle checkpoint links nuclear migration with mitotic exit. Mol. Cell 6:1-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pereira, G., and E. Schiebel. 2001. The role of the yeast spindle pole body and the mammalian centrosome in regulating late mitotic events. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13:762-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ro, H. S., S. Song, and K. S. Lee. 2002. Bfa1 can regulate Tem1 function independently of Bub2 in the mitotic exit network of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:5436-5441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakchaisri, K., S. Asano, L. R. Yu, M. J. Shulewitz, C. J. Park, J. E. Park, Y. W. Cho, T. D. Veenstra, J. Thorner, and K. S. Lee. 2004. Coupling morphogenesis to mitotic entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:4124-4129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaerer, F., G. Morgan, M. Winey, and P. Philippsen. 2001. Cnm67p is a spacer protein of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae spindle pole body outer plaque. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:2519-2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schramm, C., S. Elliott, A. Shevchenko, and E. Schiebel. 2000. The Bbp1p-Mps2p complex connects the SPB to the nuclear envelope and is essential for SPB duplication. EMBO J. 19:421-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seong, Y. S., K. Kamijo, J. S. Lee, E. Fernandez, R. Kuriyama, T. Miki, and K. S. Lee. 2002. A spindle checkpoint arrest and a cytokinesis failure by the dominant-negative polo-box domain of Plk1 in U-2 OS cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277:32282-32293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sherman, F., G. R. Fink, and J. B. Hicks. 1986. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 45.Shou, A., K. M. Sakamoto, J. Keener, K. W. Morimoto, E. E. Traverso, R. Azzam, G. J. Hoppe, R. M. Feldman, J. DeModena, D. Moazed, H. Charbonneau, M. Nomura, and R. J. Deshaies. 2001. Net1 stimulates RNA polymerase I transcription and regulates nucleolar structure independently of controlling mitotic exit. Mol. Cell 8:45-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shulewitz, M. J., C. J. Inouye, and J. Thorner. 1999. Hsl7 localizes to a septin ring and serves as an adapter in a regulatory pathway that relieves tyrosine phosphorylation of Cdc28 protein kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:7123-7137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siliciano, P. G., and K. Tatchell. 1984. Transcription and regulatory signals at the mating type locus in yeast. Cell 37:969-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song, S., T. Z. Grenfell, S. Garfield, R. L. Erikson, and K. S. Lee. 2000. Essential function of the polo box of Cdc5 in subcellular localization and induction of cytokinetic structures. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:286-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song, S., and K. S. Lee. 2001. A novel function of Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC5 in cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 152:451-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sumara, I., E. Vorlaufer, P. T. Stukenberg, O. Kelm, N. Redemann, E. A. Nigg, and J. M. Peters. 2002. The dissociation of cohesin from chromosomes in prophase is regulated by polo-like kinase. Mol. Cell 9:515-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Surana, U., A. Amon, C. Dowzer, J. McGrew, B. Byers, and K. Nasmyth. 1993. Destruction of the CDC28/CLB mitotic kinase is not required for the metaphase to anaphase transition in budding yeast. EMBO J. 12:1969-1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tanaka, K., J. Petersen, F. MacIver, D. P. Mulvihill, D. M. Glover, and I. M. Hagan. 2001. The role of Plo1 kinase in mitotic commitment and septation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. EMBO J. 20:1259-1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Verma, R., R. S. Annan, M. J. Huddleston, S. A. Carr, G. Reynard, and R. J. Deshaies. 1997. Phosphorylation of Sic1p by G1 Cdk required for its degradation and entry into S phase. Science 278:455-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]