Significance

Endosomes are membrane-bound organelles that are important for nutrient uptake, protein and lipid sorting, and signal transduction. When integral membrane proteins have reached the endosomal system, they can be sent to the lysosome for degradation or recycled for reuse. Here we provide insight into how the machinery important for reuse controls the machinery that mediates degradation. We show that these opposing functions occupy physically distinct regions of the endosomes, termed microdomains, and that this separation is likely to provide a physical framework for a variety of sorting decisions.

Keywords: endosome, SNX-1, RME-8, Hrs, clathrin

Abstract

After endocytosis, transmembrane cargo reaches endosomes, where it encounters complexes dedicated to opposing functions: recycling and degradation. Microdomains containing endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT)-0 component Hrs [hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (HGRS-1) in Caenorhabditis elegans] mediate cargo degradation, concentrating ubiquitinated cargo and organizing the activities of ESCRT. At the same time, retromer associated sorting nexin one (SNX-1) and its binding partner, J-domain protein RME-8, sort cargo away from degradation, promoting cargo recycling to the Golgi. Thus, we hypothesized that there could be important regulatory interactions between retromer and ESCRT that balance degradative and recycling functions. Taking advantage of the naturally large endosomes of the C. elegans coelomocyte, we visualized complementary ESCRT-0 and RME-8/SNX-1 microdomains in vivo and assayed the ability of retromer and ESCRT microdomains to regulate one another. We found in snx-1(0) and rme-8(ts) mutants increased endosomal coverage and intensity of HGRS-1–labeled microdomains, as well as increased total levels of HGRS-1 bound to membranes. These effects are specific to SNX-1 and RME-8, as loss of other retromer components SNX-3 and vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 35 (VPS-35) did not affect HGRS-1 microdomains. Additionally, knockdown of hgrs-1 had little to no effect on SNX-1 and RME-8 microdomains, suggesting directionality to the interaction. Separation of the functionally distinct ESCRT-0 and SNX-1/RME-8 microdomains was also compromised in the absence of RME-8 and SNX-1, a phenomenon we observed to be conserved, as depletion of Snx1 and Snx2 in HeLa cells also led to greater overlap of Rme-8 and Hrs on endosomes.

Uptake of molecules at the plasma membrane and endosomal cargo sorting are critical events for diverse cellular functions such as signaling, cell–cell junction maintenance, nutrient uptake, and development. After endocytosis, lipids and transmembrane cargo enter the early endosome for sorting. The decision to recycle or degrade a given cargo molecule, particularly signaling and adhesion molecules, is a critical and well-regulated process that goes awry in many cancers (1). At the sorting endosome, in a process largely dictated by endosomal coat proteins, cargo can be selected for degradation via delivery to the lysosome, recycling to the plasma membrane, or recycling to the Golgi via retrograde sorting.

Retromer, a coat complex mediating endosome-to-Golgi retrograde recycling, consists of a trimer of vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 35 (Vps35), Vps26, and Vps29 (previously termed the CSC) (2–4). In yeast, retromer is tightly associated with the sorting nexin (SNX) Vps5p/17p heterodimer, but, in other organisms, this link is more fragile (5–9). In Caenorhabditis elegans, the SNX-1/SNX-6 obligate heterodimer appears to function as the SNX complex most closely related to Vps5p/Vps17p (10, 11). SNX-1 and SNX-6 contain lipid binding phox homology (PX) and BAR domains. The Snx1 PX domain binds an early endosome lipid phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate [PI(3)P], and its BAR domain is capable of recognizing membrane curvature and inducing the formation of membrane tubules in vitro (12, 13). For many retromer-dependent recycling cargos, SNX-BAR–generated tubules are thought to form the active carriers for transport from endosome to Golgi (14, 15).

Similar to loss of SNX-1 or retromer components, loss of the SNX-1 binding partner RME-8 leads to missorting of retromer-dependent cargoes (16–19). RME-8 is a member of the DNAJ (J-domain containing) protein family of cochaperones that localize and activate the ATPase activity of Hsc70-family chaperones (19, 20). This chaperone activity promotes assembly and/or disassembly of protein complexes (20). For example, J-domain protein auxilin is required to disassemble clathrin from nascent endocytic vesicles shortly after they are released from the plasma membrane (21, 22). In C. elegans, Drosophila, and mammals, loss of RME-8 leads to accumulation of clathrin on internal membranes (16, 17, 23). In mammalian cells, RME-8 has also been found to associate with the WASH actin nucleation complex, and cells depleted of RME-8 accumulate Snx1 on membrane tubules decorated with Vps35 and Vps26 (16, 17, 24). In the C. elegans intestine, rme-8 mutants accumulate clathrin on the same endosomes accumulating SNX-1 (16). The relationship between retromer and clathrin on endosomes is poorly understood, and likely involves regulation occurring between retromer and components of the endosome that mediate cargo degradation, endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT).

Transmembrane cargo that is not recycled is degraded, a process that is mediated by a series of ESCRT complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, -III; reviewed in refs. 25–27). ESCRT-0 consists of Hrs and STAM, and is the first complex to recognize degradative cargo via ubiquitin interacting motifs contained in each protein (28–32). Hrs also contains a key FYVE domain, that, like the PX domain of Snx1, recognizes phospholipid PI(3)P and helps target the complex to the early endosome (33).

Retromer and ESCRT are thought to spend at least part of their lifetimes bound to the cytoplasmic face of the same endosomes. Early work by Sönnichsen et al. showed that endosomes can contain largely nonoverlapping microdomains, each marked by a distinct Rab-GTPase (Rab5, Rab4, and Rab11), leading to the idea that endosomal membranes are organized as a mosaic of physically distinct functional domains (34). Extending this idea to the degradative machinery, Raiborg and coworkers, using GTPase-defective Rab5 expression to enlarge endosomes, showed that Hrs and clathrin together form a distinct ESCRT microdomain separate from that of EEA-1 (32, 33, 35). A caveat to these studies is that the expression of GTPase-defective Rab5, used to enlarge the endosomes, clearly impairs endosome function (36–38). Subsequently, we and others suggested that the interaction of SNX-1 with RME-8 might be important for segregating microdomains enriched in retromer from domains enriched in ESCRT-0 (16, 17). This is an attractive model because regulation between microdomains with opposing functions could be important for maintaining the required balance between endosomal recycling and degradation.

Thus, we sought to test for such regulation between the retromer and ESCRT-0 microdomains in vivo. We accomplished this by taking advantage of the naturally very large (1–5 µm) endosomes of the C. elegans coelomocyte to directly visualize the interplay between degradative and retrograde sorting machinery. We found that retromer-associated SNX-1 and RME-8 not only segregate into distinct microdomains from hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (HGRS-1) in vivo, but are also important for limiting the degradative microdomain and maintaining the separation of the opposing functional microdomains. We demonstrate by live cell imaging and cellular fractionation that HGRS-1 overaccumulates on the endosomal membrane in the absence of SNX-1 and RME-8. We also show that loss of human SNX-1 homologs (SNX1 and SNX2) produces a similar effect in HeLa cells, suggesting evolutionary conservation of such microdomain interactions.

Results

C. elegans Coelomocytes Perform SNX-1– and RME-8–Dependent Recycling.

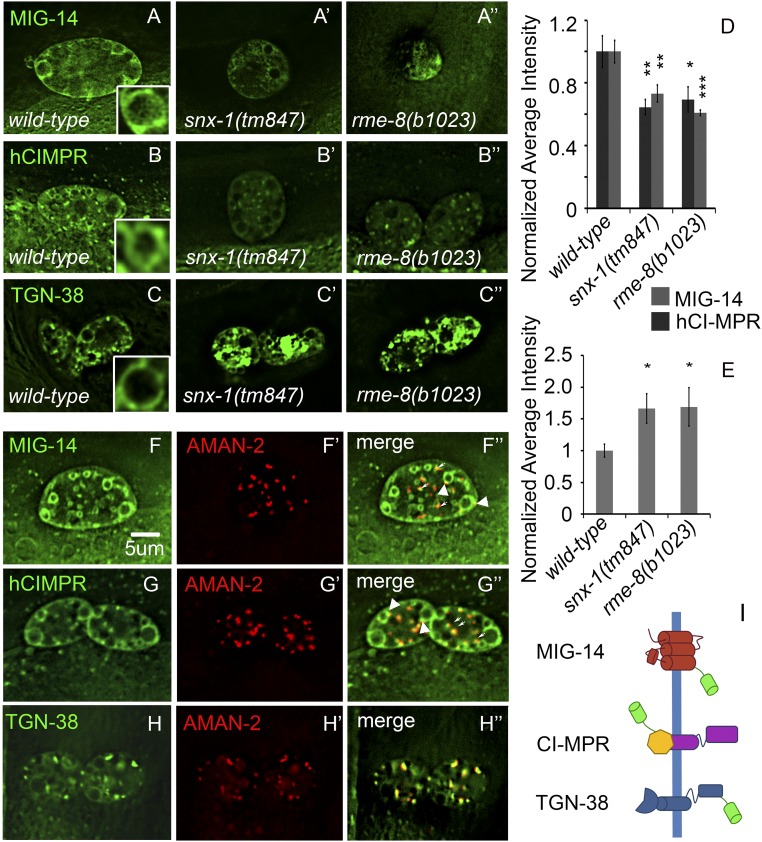

To validate C. elegans coelomocytes as a model for retrograde recycling, we expressed three different GFP-tagged, retromer-dependent transmembrane cargo proteins using the snx-1 promoter. This promoter expresses broadly but is most strongly expressed in coelomocytes. We then imaged the steady-state subcellular localization for each GFP-tagged cargo in wild-type coelomocytes, and assayed for changes in snx-1 and rme-8 mutants. These cargos included C. elegans MIG-14/Wls, human CI-MPR, and C. elegans TGN-38 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

SNX-1 and RME-8 are important for retrograde recycling in the C. elegans coelomocyte. MIG-14::GFP expressed in coelomocytes was visualized in wild-type, snx-1(tm847), and rme-8(b1023) mutant backgrounds. MIG-14 labels endosomes, internal puncta, and the plasma membrane. Note uneven distribution around the periphery of the large circular endosomes in the Inset (A–A′′). Fluorescence micrographs of hybrid-model retromer cargo composed of GFP, a portion of the human CD4-GFP extracellular domain, and the cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains of human CIMPR, expressed in wild-type, snx-1(tm847), and rme-8(b1023) mutant coelomocytes. hCIMPR-CD4-GFP labels endosomes, internal puncta, and, to a lesser extent, the coelomocyte plasma membrane. Note uneven distribution around the periphery of the large circular endosomes in the Inset (B–B′′). C. elegans TGN38/46 homolog TGN-38::GFP was expressed in the coelomocytes of wild-type, snx-1(tm847), and rme-8(b1023) mutants. TGN-38::GFP labels endosomes unevenly, strongly labels internal puncta, and weakly labels the plasma membrane (C–C′′). (Scale bar: 5 µm.) Quantification of average intensity, under the same image acquisition conditions, of each cargo in wild-type vs. mutant backgrounds (D and E). MIG-14, hCIMPR, and TGN-38 coexpressed with Golgi marker AMAN-2. Puncta (small arrows) colocalizes with Golgi marker AMAN-2::RFP (large arrowheads indicate Golgi adjacent to cargo-labeled endosomes) (F–H′′). (I) Diagrammatic representation of three cargo constructs. All experiments were performed at 25 °C.

Retrograde cargo MIG-14-GFP expressed in coelomocytes labeled the plasma membrane, endosomes, and Golgi (Fig. 1 A and F–F′′). We noted that MIG-14-GFP was typically unevenly distributed around the periphery of large ring-like endosomes, suggesting enrichment in endosomal subdomains (Fig. 1, Insets). Although coelomocytes have large round endosomes, their Golgi appear as dispersed punctate structures (i.e., ministacks), as is typical of invertebrate cells. MIG-14 is likely enriched in a different subregion of the Golgi than mannosidase AMAN-2, as it usually appeared adjacent rather than directly overlapping the AMAN-2 punctae (Fig. 1 F–F′′) (39, 40).

We expressed a CI-MPR trafficking reporter as a chimeric protein consisting of the intracellular and transmembrane domains of human CI-MPR fused to an extracellular portion of human CD4, GFP, and a secretory signal sequence (Fig. 1I). This is similar to CI-MPR-GFP chimeras used in mammalian cultured cells that traffic in a retromer-dependent manner like endogenous CI-MPR, and is also similar to an AP-2–dependent endocytosis reporter previously used in C. elegans (41, 42). CI-MPR-GFP in mammalian cells localizes to the plasma membrane, endosomes, Snx1 decorated tubules leaving endosomes, and the Golgi (4, 12). Similar to MIG-14-GFP, we found that hCI-MPR-GFP expressed in the worm labeled the coelomocyte plasma membrane, the large ring-like endosomes typical of coelomocytes, and Golgi punctae (Fig. 1 B and G–G′′).

TGN-38 expressed in coelomocytes most prominently labeled Golgi punctae, and, to a lesser extent, endosomes, similar to what has been reported in the worm intestine and in other organisms (43, 44) (Fig. 1 C and H–H′′). Taken together, the localization pattern of these three fusion proteins in C. elegans coelomocytes is consistent with that expected of recycling retromer cargo. Importantly, however, the large round endosomes in C. elegans coelomocytes allow for visualization of tagged cargo molecules with unusually clear spatial detail.

Given the well-established role for RME-8 and SNX-1 in retrograde transport of cargo in the C. elegans intestine and in cultured mammalian cells, we analyzed the effect of snx-1 and rme-8 mutants on all three retrograde cargos in coelomocytes. Previous work in C. elegans, Drosophila, and mammalian cells showed that MIG-14/Wls family proteins are misrouted to the late endosome and degraded in the lysosome when the retrograde recycling pathway is blocked (7, 16, 44–49). Similar misrouting to lysosomes upon retromer depletion has also been shown for CI-MPR in mammalian cells (4, 12, 50). Mammalian Tgn38 and C. elegans TGN-38, however, accumulate in endosomes when retrograde recycling is blocked (44, 51, 52).

To test the conservation of retrograde recycling requirements in this cell type, we analyzed changes in cargo localization and intensity in recycling mutant backgrounds. For uniformity, all experiments were done at 25 °C, the restrictive temperature for the rme-8(ts) mutant, unless otherwise stated. Consistent with other cell types, we found that, in snx-1 and rme-8 mutants, MIG-14-GFP as well as CI-MPR-GFP overall levels were reduced, and TGN-38 levels were increased (Fig. 1 A–E). The reduced level of MIG-14-GFP in snx-1 mutant coelomocytes likely results from missorting into the ESCRT pathway, as depletion of ESCRT-0 component HGRS-1 restores MIG-14-GFP to high levels (Fig. S1).

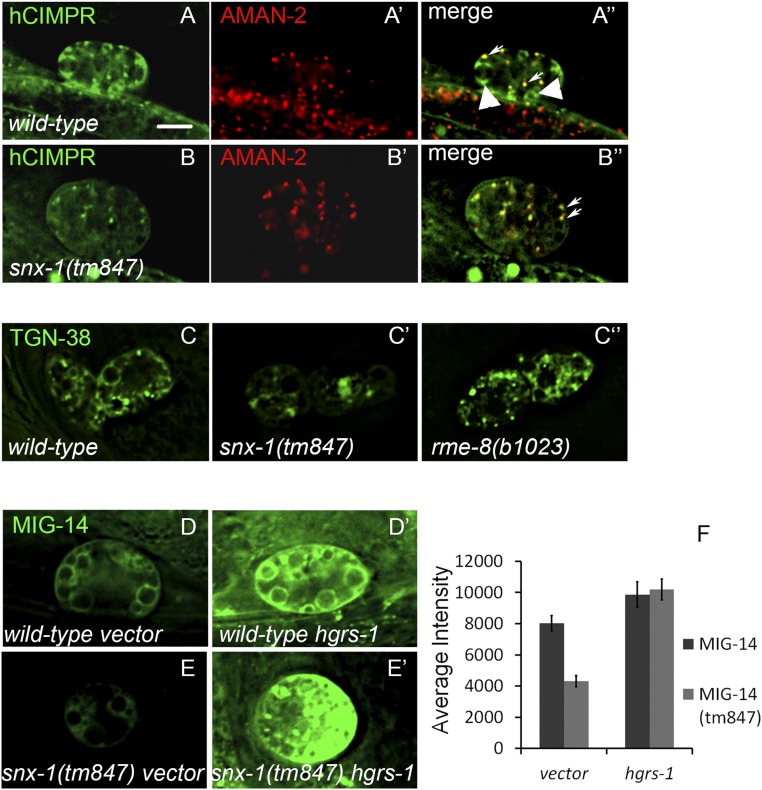

Fig. S1.

hCI-MPR labels Golgi in wild-type (A and A′′) and snx-1(tm847) (B and B′′) mutants. Large arrowheads indicate the endosomally localized hCI-MPR, which is absent in the snx-1(tm847) mutant. Small arrows indicate the hCI-MPR that colocalizes with Golgi marker AMAN-2, which is present in wild-type and snx-1(tm847) mutants. TGN-38 GFP panel from Fig. 1C is represented at lower scaling to show the morphological structures that trap TGN-38 in rme-8(b1023ts) and snx-1(tm847) mutants (C–C′′). MIG-14-GFP levels are restored in snx-1(tm847) mutants by depletion of HGRS-1. Coelomocytes expressing MIG-14 GFP wild type (D and D′) or snx-1(tm847) (E and E′) after treatment with vector (D and E) or HGRS-1 RNAi (D′ and E′). (F) Quantification of MIG-14 GFP levels in D–E′. (Scale bar: 5 µm.)

We also noted that residual hCI-MPR-GFP in snx-1 mutants localizes to the Golgi, which may represent newly synthesized hCI-MPR-GFP or residual retrograde recycling. The loss of hCI-MPR from endosomes implies that the cargo reaching endosomes is misrouted and degraded (Fig. S1).

Taken together, these results indicate that a diverse group of retrograde cargos expressed in the C. elegans coelomocyte are recycled in a manner similar to that previously described in other C. elegans cell types and other organisms (16, 44, 50, 52, 53). We conclude that coelomocytes are a valid in vivo model for studies of retrograde trafficking.

HGRS-1 Localizes in Distinct Endosomal Microdomains from Retromer-Associated Proteins.

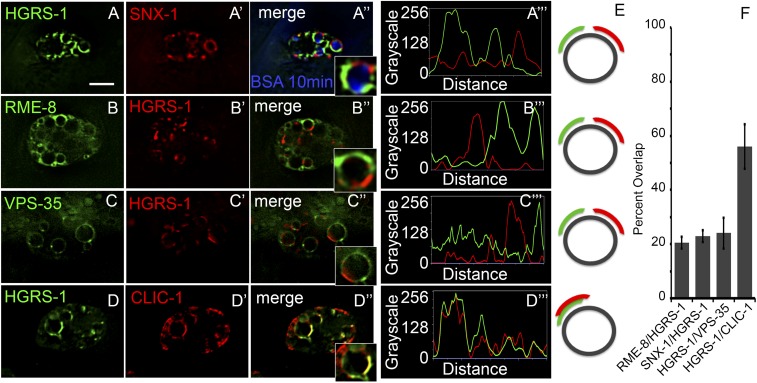

Segregation of distinct functional domains on the limiting membrane of a common endosome has long been hypothesized (32, 34, 54). Previously described molecular interactions suggest that retromer-associated proteins SNX-1 and RME-8 may regulate ESCRT to maintain a balance of recycling and degradative functions within the endosome (16–19, 23, 55). Probing this idea more directly, we took advantage of the naturally very large endosomes of coelomocytes to directly visualize the spatial relationship of RME-8/SNX-1 and ESCRT-0 component HGRS-1/Hrs.

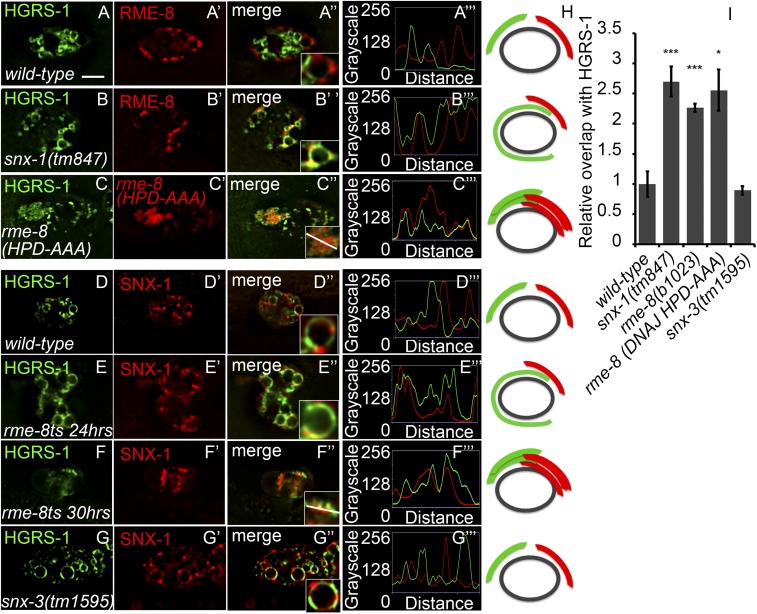

We used low copy number transgenes expressing fluorescently tagged HGRS-1 (Hrs) to mark the degradative ESCRT domain and equivalent fluorescently tagged SNX-1 and RME-8 as representatives to mark the retrograde recycling domain. In double-label experiments in coelomocytes, coupled with line scans around the limiting membrane of individual endosomes, we analyzed the relationship of the retromer and ESCRT domains. We observed that HGRS-1 localized to distinct regions of the early endosome, typically on the side of the endosome facing the interior of the cell (Figs. 2 and 3). Binding partners RME-8 and SNX-1 were enriched in regions depleted of HGRS-1, and typically on regions of the endosome facing toward the cell surface (Fig. 2 A–A′′′ and B–B′′′). Additionally, we found a similar spatial relationship between VPS-35, a core retromer protein, and HGRS-1, whereby the two proteins localized in distinct domains on a common endosome (Fig. 2 C–C′′′). Consistent with its well-established role in scaffolding the degradative domain, clathrin colocalized extensively with HGRS-1 microdomains in coelomocytes (Fig. 2 D–D′′′). These data indicate that physically distinct microdomains exist for functionally distinct proteins on a common endosome.

Fig. 2.

Retromer-associated proteins RME-8 and SNX-1 specifically label endosomal microdomains complementary to that of ESCRT-0 protein HGRS-1. Images are shown of coelomocytes within intact living animals expressing citrine::HGRS-1 and tagRFP::SNX-1 that have been allowed to take up Cy5-BSA from the body cavity for 10 min (A–A′′). A line scan displaying pixel intensity around the periphery of one endosome (as visualized in A′′, Inset) shows complementary localization of HGRS-1 and SNX-1 on the Cy5-BSA filled endosome (A′′′). Citrine::RME-8 and tagRFP::HGRS-1 label distinct microdomains (B–B′′). A line scan of the endosome limiting membrane (B′′, Inset) indicates complementary localization of HGRS-1 and RME-8 (B′′′). Endogenous VPS-35 tagged with GFP labels microdomains distinct from citrine::HGRS-1 (C–C′′). Line scan of the endosome in C′′, Inset (C′′′). Citrine::HGRS-1 and CLIC-1::tagRFP colocalize in discrete microdomains on the endosome (D–D′′). Line scan of the endosome in D′′, Inset (D′′′). (Scale bar: 5 µm.) Diagrammatic representation of the localization of the endosomal components to the right of the relevant line scans (E). (F) Quantification of colocalization of the endosomal components of A–D.

Fig. 3.

HGRS-1 and SNX-1 microdomains are enriched in relevant cargo. (A–A′′) Peaks in intensity of MIG-14::tagRFP (pseudocolored green) along the endosomal periphery coincide with GFP::SNX-1 (pseudocolored red). (A′′′) Two-color line scan around the endosomal periphery (A′′, Inset). (B–B′′) MIG-14::GFP and tagRFP::HGRS-1 display complementary microdomain enrichment. (B′′′) Two-color line scan around the endosomal periphery (B′′, Inset). (C–C′′) Cy3-BSA is enriched in citrine::HGRS-1–labeled microdomains after 5 min of uptake. (C′′′) Two-color line scan around the endosomal periphery (C′′, Inset). (Scale bar: 5 µm.) (D) A diagrammatic representation of the panels is displayed to the right. (E) Quantification of colocalization of relevant cargo and endosomal components of A–C.

HGRS-1 and SNX-1 Localization Represents Functionally Relevant Domains on the Endosome.

We next investigated whether spatially distinct domains on the endosome associated with relevant cargo. If these domains were functionally important for sorting cargo, we would expect retrograde cargo to be enriched in SNX-1/RME-8–labeled domains, but not in HGRS-1–labeled domains. Indeed, we observed that peaks in intensity of SNX-1 on the endosome colocalized with peaks in intensity of MIG-14 (Fig. 3 A–A′′′; Fig. 3E for illustration). As expected, peaks of recycling cargo MIG-14 were inversely correlated with peaks of ESCRT component HGRS-1 (Fig. 3 B–B′′′).

If such domains are functionally relevant, we would also expect degradation-bound cargo to colocalize with the degradative machinery. To visualize degradative transport from the early endosome to the late endosome and lysosome, we followed the uptake of BSA. Fluorescently labeled BSA injected into the pseudocoelom is actively endocytosed by coelomocytes, probably via scavenger receptors. BSA then travels through RME-8-GFP–labeled endosomes to reach lysosomes (19, 56). After injection into the worm pseudocoelom, labeled BSA appears within coelomocyte endosomes within 5 min, soon thereafter appearing concentrated in discrete subregions within the early endosome, before appearing in late endosomes approximately 20 min after injection (19, 57–59). Consistent with HGRS-1 labeling a functional degradative domain, we observed robust colocalization between HGRS-1 and degradation bound Cy5-BSA 5 min after uptake from the pseudocoelom (Fig. 3 C–C′′′). These data suggest that the complementary domains marked by SNX-1 and HGRS-1 represent functional and dynamic sorting domains.

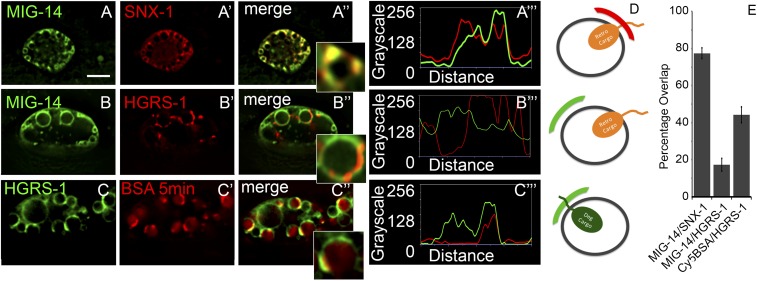

SNX-1 and RME-8 Limit the Degradative Domain.

Given the effects of J-domain proteins in the disassembly of protein complexes, we hypothesized that SNX-1 could be acting through RME-8 and Hsc70 to limit the growth of the ESCRT subdomain (20). If SNX-1 and RME-8 were indeed limiting the assembly of the degradative ESCRT subdomain, we would expect HGRS-1 to overaccumulate on the endosome in the absence of SNX-1 or RME-8. To test this hypothesis, we measured HGRS-1 accumulation on the endosome in three different ways: percent coverage of the endosome limiting membrane by YFP::HGRS-1, fluorescence intensity of YFP::HGRS-1, and the degree of membrane association of endogenous HGRS-1 in C. elegans lysates as measured by fractionation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

HGRS-1 endosomal occupancy is controlled by SNX-1, SNX-6, and RME-8. (A–A′′ and B–B′′) Fluorescence and DIC images of coelomocytes expressing citrine::HGRS-1 in wild-type and snx-1 mutant backgrounds. Quantification of average citrine::HGRS-1 endosomal occupancy in wild-type and snx-1 mutant strains (C). Membrane association of endogenous HGRS-1 was measured by Western blot after lysis and ultracentrifugation to separate membranes from cytosol in wild-type, snx-1(tm847), and rme-8(b1023) mutant strains. The fraction is indicated above the lane. Equivalent samples were loaded in each lane. The ratios of 100P vs. supernatant and 18P vs. supernatant are indicated below the two fractions. In rme-8 and snx-1 mutants, the 18P and 100P fractions contain proportionally more HGRS-1 than in wild type. RME-2 is a transmembrane yolk receptor that fractionates only with the membranous fractions (D). (E–K) Citrine::HGRS-1 imaged in wild-type, snx-1(tm847), snx-6(tm3790), rme-8(b1023), snx-3(tm1595), and vps-35(hu68) mutant strains with the same exposure and scaling conditions at 25 °C. (L) Quantification of citrine::HGRS-1 intensity in wild-type and mutant backgrounds. (Scale bar: 5 µm.)

By using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy to help define endosome boundaries, and using a blinded system, we scored the percentage of an endosome that was occupied by YFP::HGRS-1. We found a significant increase in endosomal coverage of HGRS-1 in snx-1(tm847) deletion mutants (Fig. 4 A–C). Furthermore, we found a marked increase in YFP::HGRS-1 intensity in snx-1(tm847) and rme-8(b1028ts) mutants (Fig. 4 E–I, quantified in Fig. 4L), but no increase in total YFP::HGRS-1 protein levels (Fig. S2), indicating a greater degree of HGRS-1 assembly on membranes in snx-1 and rme-8 mutants. Additionally, the absence of SNX-6, an obligate SNX-1 binding partner, produced a similar accumulation of HGRS-1 on endosomes (Fig. 4G).

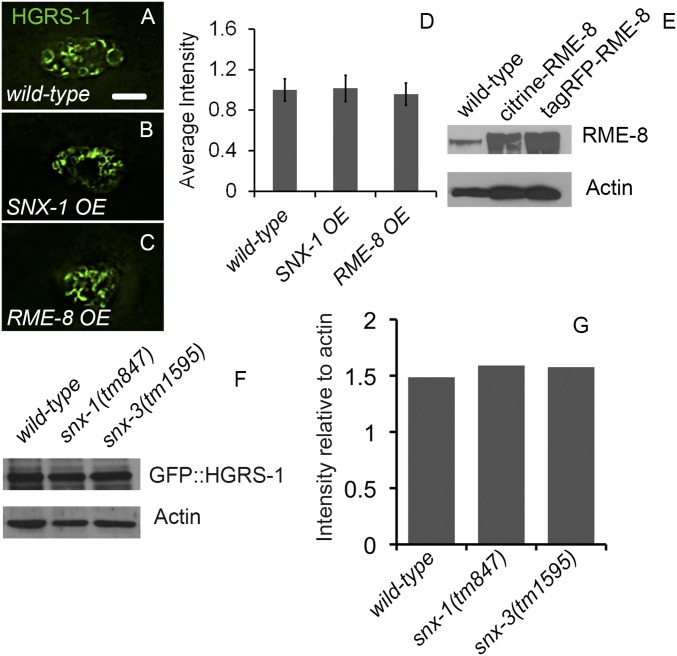

Fig. S2.

HGRS-1 intensity is not affected by SNX-1 or RME-8 overexpression, and total protein levels are unchanged in snx-1 and snx-3 mutants. Coelomocytes expressing citrine::HGRS-1 alone (A) or in the presence of SNX-1::tagRFP or tagRFP::RME-8 (B and C). (D) Levels of citrine::HGRS-1 from A–C quantified. Measurement of levels of RME-8 in wild type vs. citrine- and tagRFP-tagged transgenes. Actin was used as a loading control (E). Animals expressing GFP:HGRS-1 in wild-type, snx-1, and snx-3 mutants were lysed, run on SDS/PAGE, and probed for GFP. Actin was used as a loading control (F). (G) Quantification of F. (Scale bar: 5 µm.)

To test the effects on endogenous HGRS-1, we separated C. elegans lysates into cytoplasmic and membrane fractions by using ultracentrifugation. Fractions were isolated at 18,000 × g [18,000 × g pellet (18P)] containing larger membrane structures, followed by 100,000 × g [100,000 × g pellet (100P)] containing smaller remaining membranes, leaving a final 100,000 × g supernatant (100S) containing soluble cytoplasm. We compared the relative amount of endogenous HGRS-1 in pellet fractions vs. cytoplasmic fractions by Western blot, using transmembrane receptor RME-2 as a measure of the fidelity of segregation of membranes into the pellet fractions. In snx-1 and rme-8 mutants, the ratio of HGRS-1 found in the small (100P) and large membrane (18P) fractions to that found in the cytosolic fraction increased compared with wild-type controls. Ratios of pellet/cytoplasmic HGRS-1 are noted below the 18P and 100P fractions in Fig. 4D. Taken together, our results indicate that SNX-1, SNX-6, and RME-8 play an important role in limiting HGRS-1 assembly on the early endosome.

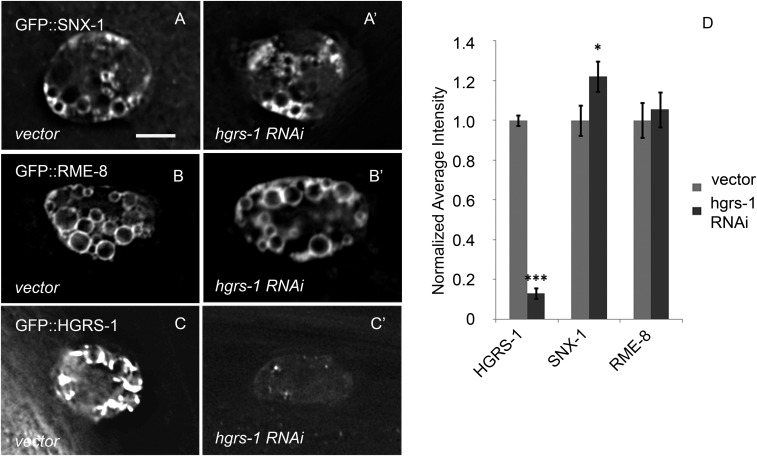

The strong effect of loss of SNX-1 and RME-8 function on the membrane accumulation of HGRS-1 did not appear reciprocal. Knockdown of HGRS-1 by RNAi produced no change in RME-8::GFP endosome association and led to only a slight increase in endosomally localized SNX-1::GFP (Fig. S3 A–C). The efficiency of HGRS-1 knockdown in coelomocytes was confirmed by RNAi in YFP::HGRS-1–expressing strains (Fig. S3C). Unlike the accumulation of HGRS-1 on the endosome in the absence of SNX-1 or RME-8, the opposite is not true. We assayed for effects of increased expression of RME-8 or SNX-1 on HGRS-1 endosome association, but did not find a significant effect (Fig. S2). These results suggest that the interaction SNX-1/RME-8 with ESCRT is probably regulated at the level of functional activity, and support the idea that these visualized domains are functionally relevant.

Fig. S3.

HGRS-1 is not important for limiting RME-8 or SNX-1 endosomal domains. Strains expressing GFP::SNX-1 were treated with empty vector RNAi control (A) or hgrs-1 RNAi (A′). Strains expressing GFP::RME-8 were treated with empty vector RNAi control (B) or hgrs-1 RNAi (B′). Strains expressing GFP::HGRS-1 were treated with empty vector RNAi control (C) or hgrs-1 RNAi (C′). The fluorescence intensity of GFP::SNX-1, GFP::RME-8, and GFP::HGRS-1 was quantified in control vs. hgrs-1 RNAi (D). (Scale bar: 5 μm.)

SNX-1/RME-8 Maintain Separation of Distinct Microdomains.

We next sought to determine if retrograde and degradative domains remained separate in the absence of SNX-1 or RME-8. In strains expressing YFP::HGRS-1 and tagRFP::RME-8, we observed an increase in overlap of HGRS-1 with RME-8 in an snx-1 mutant, as measured by colocalization analysis and line scans along the circumference of endosomes (Fig. 5 A–B′′′, and I; Fig. 5H for illustrations). Similarly, we found that the separation of SNX-1 and HGRS-1 was diminished in an rme-8(b1028ts) mutant (Fig. 5 D–F′′′ and I). Taken together, these results demonstrate that functional RME-8 and SNX-1 are required for maintenance of separate domains on the endosome.

Fig. 5.

RME-8 and SNX-1 control microdomain separation. Strains expressing citrine::HGRS-1 and tagRFP::RME-8 display complementary microdomains (A–A′′′). (B–B′′′) snx-1(tm847) mutants expressing citrine::HGRS-1 and tagRFP::RME-8 display an increase in overlap of the normally separate domains. (C–C′′′) Coelomocytes expressing tagRFP::HGRS-1 (pseudocolored green) and GFP::RME-8(DNAJ-HPD-AAA) (pseudocolored red) display an increase in overlap of the normally separate domains, as well as an altered morphology of the endosomal components HGRS-1 and RME-8. (D–D''') Citrine::HGRS-1 and tagRFP::SNX-1 in wild-type coelomocytes display complementary microdomain localization. (E–E′′′) rme-8(b1023) mutant coelomocytes expressing citrine::HGRS-1 and tagRFP::SNX-1 display an increase in overlap of the normally separate domains 18 h after temperature shift. (F–F′′′) At 30 h after temperature shift, endosomes are no longer recognizable, and citrine::HGRS-1 and tagRFP::SNX-1 display an increase in overlap of the normally separate domains. (G–G′′′) Strains expressing citrine::HGRS-1 and tagRFP::SNX-1 in snx-3(tm1595) worms display wild-type complementary localization. (H) Overlap of endosomal microdomains is quantified. (I) A diagrammatic representation of endosomal microdomain localization of the panels to the left. (Scale bar: 5 µm.)

As the b1023 allele of rme-8 is temperature-sensitive, the pattern of HGRS-1 accumulation varied depending on the amount of time spent at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 4 H and I). This, however, did not affect the extent of overlap between SNX-1 and HGRS-1 (Fig. 5 E–F′′′). After 18–24 h at the restrictive temperature, HGRS-1 accumulated around the endosome circumference evenly; however, after 30 h, HGRS-1 accumulated in an irregular pattern on the endosome (compare Fig. 4H vs. Fig. 4I). This irregular HGRS-1 localization in an rme-8 ts mutant was strikingly similar to its localization in strains expressing a form of RME-8 in which we mutated the DNAJ domain catalytic amino acids HPD (amino acids 1353–1355) to AAA (compare Fig. 5C vs. Fig. 5F) (60–62). We found that expression of the DNAJ mutant in coelomocytes increased the overlap between the normally separate HGRS-1 and RME-8 domains (Fig. 5 C–C′′′) and also mimicked the endosomal morphology of later time points in temperature shift of the ts allele of rme-8 (Fig. 5 F–F′′′). These results suggest that the catalytic activity of RME-8 as a J-domain cochaperone for Hsc70 is important for RME-8 function in microdomain separation.

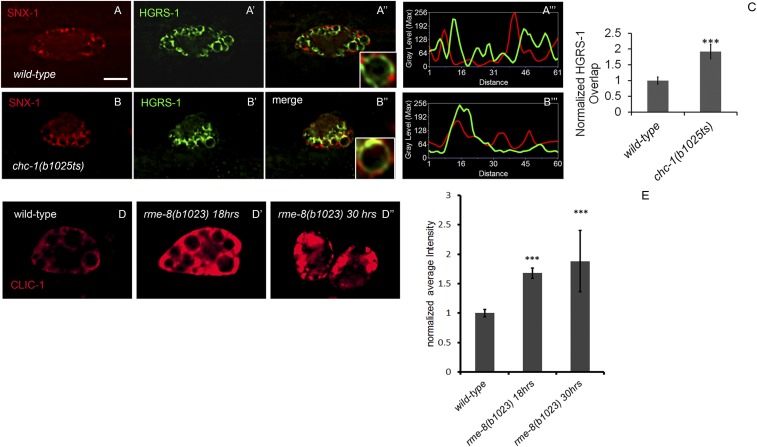

As the endosomal flat clathrin lattice is a potential RME-8 target that has been proposed to bind to ESCRT-0 and organize the ESCRT domain, we also assayed for changes in microdomain separation in a temperature-sensitive mutant of clathrin heavy chain (54, 63–65). We found increased overlap of tagRFP-SNX-1 and citrine-HGRS-1 in chc-1(b1025ts) mutants at the restrictive temperature, consistent with a role for clathrin in maintaining microdomain separation (Fig. S4).

Fig. S4.

Clathrin accumulates in the absence of RME-8 in coelomocytes, and loss of clathrin impairs microdomain separation. Strains expressing citrine::HGRS-1 and tagRFP::SNX-1 display complementary microdomains (A–A′′′). chc-1(b1025ts) mutants expressing citrine::HGRS-1 and tagRFP::SNX-1, shifted to the nonpermissive temperature overnight, display an increase in overlap of the normally separate domains (B–B′′′). Quantification of the overlap of citrine::HGRS-1 and tagRFP::SNX-1 normalized to wild type in the chc-1(b1025ts) mutant background (C). Clathrin light-chain (Clic-1)::tagRFP imaged in wild-type and rme-8(b1023) mutant strains with the same exposure and scaling conditions shifted to 25 °C for the indicated time (D–D′′). Quantification of CLIC-1::tagRFP in wild-type and mutant backgrounds (E). (Scale bar: 5 µm.)

Not All Retromer Associated Proteins Are Important for Domain Maintenance.

Retromer protein VPS-35/Vps35 and retromer-associated protein SNX-3/Snx3 are key components for retrograde recycling in many different organisms. In C. elegans, SNX-3 and VPS-35 have been found to regulate the proper sorting of retrograde cargo MIG-14, Type I TGF-β receptor SMA-6, and TGN-38 (7, 44, 66). As our aforementioned results indicate that retromer associated proteins RME-8 and SNX-1 limit HGRS-1 degradative domain size, we also investigated the role of VPS-35 and SNX-3 in maintaining the degradative domain. We found that HGRS-1 distribution around the endosomal periphery was unchanged in putative null mutants of vps-35 and snx-3 compared with wild type (Fig. 4 J–L). Additionally, we found that snx-3 mutants displayed a normal separation of YFP-HGRS-1 and tagRFP-SNX-1 domains (Fig. 5 G and I). These results suggest that only a subgroup of retromer associated proteins contribute to the maintenance of spatially distinct domains on the endosome.

Human SNX-BAR Proteins Snx1 and Snx2 Are Important for Microdomain Separation.

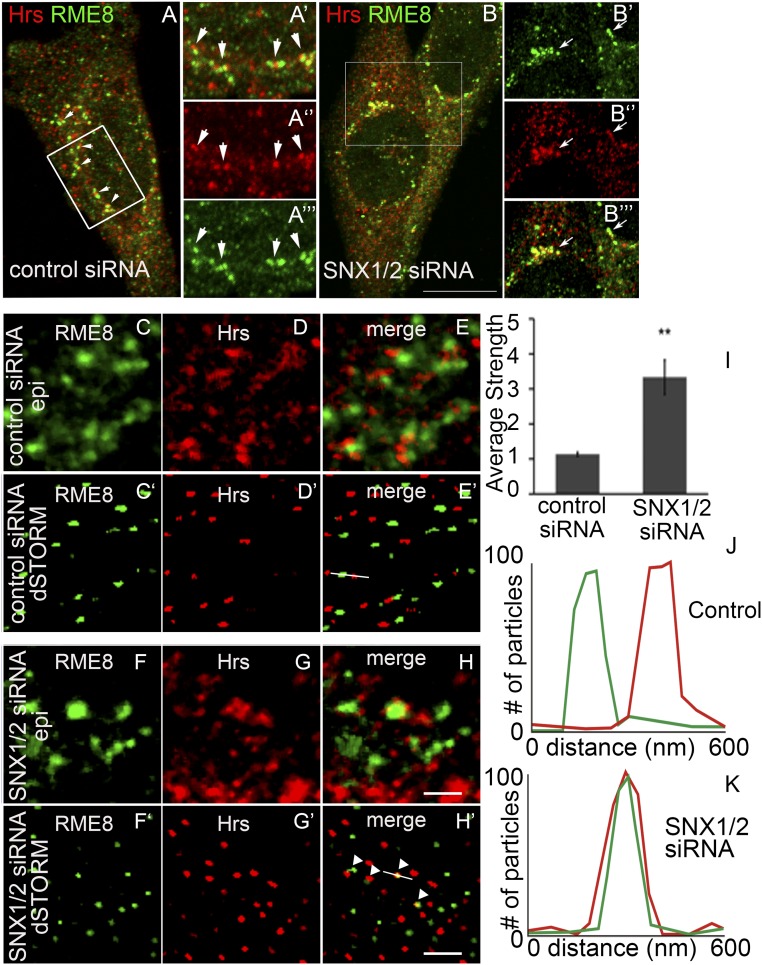

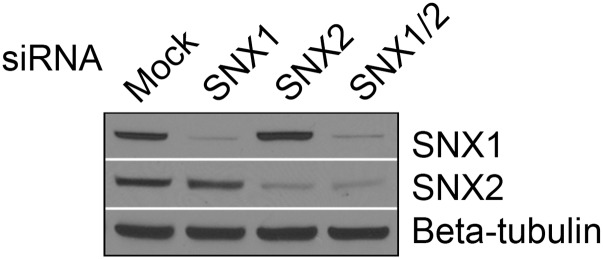

To assay for conservation of SNX-1 family proteins in restricting the ESCRT-0 domain within endosomes, we used siRNAs in HeLa cells to knock down expression of human SNX-1 homologs Snx1 and Snx2, assaying for effects on the localization of endogenous Hrs and RME-8 by immunofluorescence (53). Endosomes in HeLa cells are smaller than those in coelomocytes, so domains on such endosomes typically manifest as shoulder-to-shoulder localization (Fig. 6 A–A′′′, C–E, and J) (67). If SNX1 and SNX2 are required to keep RME-8 and Hrs microdomains separate, we would expect that removal of Snx1 and Snx2 by siRNA would lead to increased colocalization of Hrs and RME-8 on endosomes. Although endosomes far from the nucleus appeared unaltered, we often observed greater overlap of RME-8 and Hrs in endosomes near the nucleus after Snx1/2 depletion (Fig. 6 B–B′′′, H, H′, I, K and Fig. S5). Given that the Golgi is a perinuclear structure, such endosomes may be among those most active in endosome-to-Golgi trafficking.

Fig. 6.

The role of SNX-1 in microdomain separation is conserved in HeLa cells. Confocal microscopy of endogenous Hrs and RME-8 display a shoulder to shoulder localization in the perinuclear region in control cells. Arrows indicate the juxtaposition of Hrs and RME-8 immunostaining (A–A′′′). Under conditions of SNX1/2 siRNA, RME-8– and Hrs-labeled domains colocalize in enlarged structures in the perinuclear area. Arrows indicate the enlarged endosomes positive for colocalized RME-8 and Hrs (B–B′′′). dSTORM (C′–H′) vs. epifluorescent (C–H) images of endogenous Hrs and RME-8 transfected with control scrambled siRNA (C–E and C′–E′) and SNX1/2 siRNA (F–H and F′–H′). Arrows indicate RME-8 and Hrs that are close and/or colocalized. Nearest-neighbor analysis strength of interaction of Hrs and RME-8 is significantly increased upon SNX1/2 siRNA (I). Quantification of line scans shown in E′ (J) and H′ (K).

Fig. S5.

Western blot of HeLa cell lysates probed for Snx1 or Snx2 indicate efficient knockdown.

To further investigate the nature of Hrs- and RME-8–labeled domains beyond the limit of diffraction, direct stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (dSTORM) was performed on immunofluorescent samples using conventional fluorophores (68). Because the images in STORM data represent a reconstruction of locations and localization uncertainties of individual molecules, the overlap of signal in images is not the best method for determining whether molecules colocalize. Instead, we used a nearest-neighbor analysis to determine how close each point source is to its nearest neighbor by using the “strength” metric (69, 70). Supporting the hypothesis of microdomain mixing, we found that, upon Snx1/2 depletion, the interaction strength between RME-8 and Hrs increased significantly [3.33 (n = 3) compared with 1.13 (n = 3) for control; P < 0.02, t test; Fig. 6I). These results demonstrate that Hrs and RME-8 were in closer proximity to each other after Snx1/2 knockdown, suggesting that Snx1/2 play a conserved role in preventing intermixing of retrograde and degradative domains on endosomes.

Discussion

There is mounting evidence that endosomes are a mosaic of functional domains consisting of transmembrane cargo, lipids, and peripheral membrane proteins (71). These domains are segregated and yet dynamic, changing over space and time, i.e., as an endosome matures, it changes in structure and function. For example, different tubules emanating from the vacuolar region of an early/sorting endosome contain different Rabs, SNXs, and hence different cargo bound for various destinations (34, 71–73). In addition to differentially coated tubules, our understanding of domain segregation on the vacuolar region is developing. One proposed endosomal microdomain type revolves around an endosomal flat clathrin lattice, described initially more than 30 years ago as plaques by immunofluorescence in cells, and later revealed by immuno-EM to contain Hrs, STAM, and cargo proteins (refs. 32, 35, 74–76; reviewed in ref. 77). More recent work implicates this domain in transmembrane cargo degradation via scaffolding of ESCRT-0 component Hrs, which in turn concentrates ubiquitinated cargo (32, 35, 78–80).

Development of a System to Investigate Endosomal Microdomains.

Immuno-EM analysis was key in revealing subendosomal localization of trafficking machinery, but can be limited by artifacts induced by sample fixation and by issues of sensitivity (77). Light microscopy has not typically provided sufficient resolution to investigate the interplay of microdomains, unless endosomes are enlarged by artificial means that also impair endosome function. Additionally, high-resolution microscopy often involves powerful light sources that damage tissues (81, 82). Here we have developed a system to directly visualize the retromer and ESCRT-0 microdomains in vivo, within live, intact animals, taking advantage of the naturally large endosomes of highly endocytically active coelomocyte cells of C. elegans. We demonstrate that the C. elegans coelomocyte is active in retrograde recycling, and displays impressive spatial segregation of retromer-associated recycling and ESCRT-associated degradative domains. Furthermore, we found that SNX-1 and RME-8 limit the degradative domain and keep it separated from the retrograde domain, providing insights into mechanisms that support robust and balanced cargo sorting. Most likely, there are other microdomains that exist concomitantly with ESCRT-0, and this system provides a robust platform for future investigations.

Specific Roles for RME-8/SNX-1.

The microdomains we identified appear to represent functional structures, as they are enriched in the appropriate recycling or degradative cargo, and their proper separation depends on retromer-associated proteins SNX-1, SNX-6, and RME-8, and the integrity of the RME-8 J-domain (Figs. 3 and 5). In the absence of these retromer-associated proteins, the HGRS-1 domain spreads around the endosome, and more HGRS-1 is recruited from the cytoplasm onto membranes, whereas removal of HGRS-1 had minimal effect on the distribution of SNX-1 or RME-8 on the endosome (Fig. 4). The role of limiting the degradative sorting domain, however, is not shared by all retrograde sorting components, as VPS-35 and SNX-3 do not affect the HGRS-1 domain, despite being required for proper cargo recycling and, as is the case for VPS-35, displaying complementary microdomain localization (Figs. 2 and 4). Additionally, microdomain separation is also not perturbed upon loss of SNX-3, further demonstrating that multiple mechanisms contribute to proper cargo sorting (Fig. 5). When SNX-1 or RME-8 is absent, or the RME-8 DNAJ domain is mutated, the microdomains mix. Intriguingly, the mixing is not complete, suggesting that additional mechanisms exist to keep the domains separate.

RME-8/SNX-1 vs. the Degradative Domain.

Previous work has demonstrated that, in the absence of SNX-1, RME-8, or Hsc70/HSP-1, clathrin is less dynamic and accumulates on endosomes. Additionally, in the absence of these components, sorting of retrograde cargo MIG-14, StxB, and CI-MPR is disrupted (16, 17). Overaccumulation of membrane-associated clathrin also occurs in coelomocytes (Fig. S4), Drosophila, and mammalian cells upon loss of RME-8, suggesting that clathrin may be a direct target (83–85). In addition to helping to recognize cargo bound for degradation, Hrs also recruits clathrin to the endosome, and clathrin has been proposed to scaffold ESCRT and degradative cargo, a function that may help to define a degradative subdomain (32, 54, 78, 86). Additionally, our data indicate that reduction of functional clathrin also results in mixing of the normally separate HGRS-1 and SNX-1 microdomains (Fig. S4). That loss of clathrin and accumulation of clathrin are correlated with defects in microdomain maintenance suggests that endosomal clathrin is instructive in directing competing complexes as to their proper position and degree of assembly.

In addition, Drosophila and mammalian Snx1 proteins are known to bind to Hrs in vivo and in vitro, and Hrs has also been reported to interact with retromer component Vps35 (17, 55). Thus, direct interactions between retromer and ESCRT may also play a role in the regulatory interactions we have observed. These interactions likely occur on the vacuolar region of the endosome as opposed to the tubules. Although SNX-1 has well-established membrane tubulating activities, its binding partner RME-8 is not found on tubules. These results are consistent with the idea that SNX-1 and RME-8 work together on the vacuolar region of the endosome to limit the degradative microdomain.

We also note that HGRS-1 not only overaccumulates, but also appears to aggregate when the RME-8 DNAJ domain is mutated or after extended time periods in rme-8(ts) mutants at the restrictive temperature (Figs. 4 I and 5 C–C′′′ and F–F′′′). Golgi ministacks are often adjacent to endosomes in coelomocytes, and endosomes are very large in coelomocytes (Fig. 1), potentially shortening the distance for endosome to Golgi trafficking and making visualization of retromer tubules difficult. Hence, this clumped morphology upon long perturbation of RME-8 function in coelomocytes may be akin to the ectopic tubulation observed in mammalian cells. Upon depletion of RME-8, accumulation of sorting components such as WASH and FAM21, as well as Snx1 and retrograde cargo decorating endosomal tubules, has been observed (17, 24, 87). This could represent indirect effects via clathrin and ESCRT, or may represent additional direct targets of RME-8–stimulated Hsc70-chaperone activity on the endosome, as hypothesized by Freeman et al. (24).

Our data indicate that retromer cross-regulates ESCRT to maintain an appropriate balance of each activity within a given endosome. The ESCRT and retromer pathways drive opposing endosomal functions that must somehow coexist; therefore, understanding the segregation of ESCRT and retromer domains on the endosome may be particularly relevant to understanding endosome function. We propose that an antagonistic relationship between retromer-associated proteins and ESCRT is important for maintaining a balance of opposing sorting activities within an endosome. These activities may be particularly important to rebalance such activities as cargo load distribution change and cellular physiology changes to keep pace with the cellular environment.

Materials and Methods

All C. elegans strains were derived originally from the wild-type Bristol strain N2. Worm cultures, genetic crosses, and other C. elegans husbandry were performed according to standard protocols (88). A complete list of strains used in this study is provided in Table S1. Additional methods are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Table S1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain name | Genotype | Ref. |

| RT2734 | pwIs995[psnx-1::mig-14::gfp-unc54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; pwIs1022[psnx-1::aman-2(aa1-82)::tagRFP unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119] | This study |

| RT2681 | pwIs976[psnx-1::clic-1::gfp-cb-unc-119]; unc-119(ed3) | This study |

| RT2764 | pwIS1039[psnx-1-citrine::hgrs-1::unc54-3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; unc-119(ed3) | This study |

| RT2797 | pwIs1010[psnx-1::snx-3::tagRFP-unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; pwIS1039[psnx-1-citrine::hgrs-1::unc-54-3′UTR-cb-unc-119] | This study |

| RT2800 | pwIs984[psnx-1::tagRFP::snx-1genomic-cb-unc-119]; pwIS1039[psnx-1-citrine::hgrs-1::unc-54-3′UTR-cb-unc-119] | This study |

| RT2861 | pwIs995[psnx-1::mig-14::gfp-unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; snx-1(tm847) | This study |

| RT2702 | pwIs995[psnx-1::mig-14::gfp-unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; unc-119(ed3) | This study |

| RT2864 | pwIs995[psnx-1::mig-14::gfp-unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; pwIs984[psnx-1::tagRFP::snx-1genomic-cb-unc-119] | This study |

| RT2866 | pwIs995[psnx-1::mig-14::gfp-unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; rme-8(b1023) | This study |

| RT2869 | pwIs1019[psnx-1::clic::tagRFP-unc-54-3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; pwIS1039[psnx-1-citrine::hgrs-1::unc-54-3′UTR-cb-unc-119] | This study |

| RT2874 | pwIs1053[psnx-1tagRFP::rme-8::unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; pwIS1039[psnx-1-citrine::hgrs-1::unc-54-3′UTR-cb-unc-119] | This study |

| RT2914 | pwIS1039[psnx-1-citrine::hgrs-1::unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; snx-3(tm1595) | This study |

| RT2926 | pwIs984[psnx-1::tagRFP::snx-1genomic-cb-unc-119]; pwIS1039[psnx-1-citrine::hgrs-1::unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; snx-3(tm1595) | This study |

| RT2927 | pwIs995[psnx-1::mig-14::gfp-unc54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; pwIs1038[psnx-1::hgrs-1::tagRFP-unc54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119] | This study |

| RT2934 | pwIS1039[psnx-1-citrine::hgrs-1::unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; snx-1(tm847) | This study |

| RT2972 | pwIs1175[psnx-1::tgn-38::gfp-unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; unc-119(ed3) | This study |

| RT2973 | pwIs1176[psnx-1::ss-gfp-cd4-hcimpr::unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; unc-119(ed3) | This study |

| RT2989 | pwIs1176[psnx-1::ss-GFP-cd4-hcimpr::unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; snx-1(tm847) | This study |

| RT2990 | pwIs1175[psnx-1::tgn-38::gfp-unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; snx-1(tm847) | This study |

| RT2940 | pwIS1039[psnx-1-citrine::hgrs-1::unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; rme-8(b1023) | This study |

| RT3086 | pwIs1176[psnx-1::ss-gfp-cd4-hcimpr::unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; pwIs1022[psnx-1::aman-2(aa1-82)::tagRFP-unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119] | This study |

| RT3139 | pwIs1019[psnx-1::clic-1::tagRFP-unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; rme-8(b1023) | This study |

| RT3140 | pwIs1176[psnx-1::ss-GFP-cd4-hcimpr::unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; rme-8(b1023) | This study |

| RT3141 | pwIS1039[psnx-1-citrine::hgrs-1::unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; pwIs984[psnx-1::tagRFP::snx-1genomic-cb-unc-119]; rme-8(b1023) | This study |

| RT3173 | pwIs1175[psnx-1::tgn-38::GFP unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; rme-8(b1023) | This study |

| RT3174 | pwIs1175[psnx-1::tgn-38::GFP unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; snx-3(tm1595) | This study |

| RT3197 | pwIS1039[psnx-1-citrine::hgrs-1::unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; snx-6(tm3790) | This study |

| RT3199 | pwEX150[pcup-4-gfp::rme-8minigene(HPD-AAA)::unc-54 3′UTR-cb-unc-119]; unc-119(ed3) | This study |

SI Materials and Methods

RNAi.

RNAi was performed by using the feeding method (89). Feeding constructs were from the Ahringer library (90) or prepared by PCR from EST clones provided by Yuji Kohara (National Institute of Genetics, Mishima, Japan) followed by subcloning into the RNAi vector L4440 (89). Synchronized worms were incubated on RNAi plates at 15 °C until F1s were at the L2/L3 stage, then shifted to 25 °C for the indicated time and imaged.

HeLa Cell Culture and Transfection.

HeLa cells were cultured with high glucose DMEM containing sodium pyruvate and l-glutamine supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS at 37 °C and 5% (vol/vol) CO2. Transient transfection of HeLa cells was performed by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). SMARTpool siRNA oligonucleotides (100 pmol) of SNX1 (M-017518; Dharmacon/Invitrogen) and SNX2 (M-017520) were transfected into HeLa cells twice with 24-h intervals. Following transfection, cells were cultured for an additional 1 d before harvesting for biochemical analysis. Following a BCA assay, equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were resolved by 4–12% (wt/vol) Bis-Tris PAGE for sequential Western blots on the same membranes after stripping between each application of the antibody.

Confocal Imaging of HeLa Cells.

For immunostaining, cultured cells were fixed with 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde at room temperature (RT) for 20 min, washed three times with PBS solution for 5 min each, and then incubated in 0.4% saponin (no. S4521; Sigma), 5% (vol/vol) normal goat serum (no. G9023; Sigma), and 2% (wt/vol) BSA (no. A2153; Sigma) in PBS solution for 1 h. Fixed cultures were incubated with primary antibodies in PBS solution with 2% (wt/vol) BSA and 0.4% saponin at 4 °C overnight. Cells were washed four times with PBS solution at RT for 5 min each, incubated with secondary fluorescent antibodies (Invitrogen) at 1:400 dilution in PBS solution with 2% (wt/vol) BSA and 0.4% saponin for 30 min, rewashed with PBS solution, and then mounted with Fluor-Gel anti-fade mounting medium (EMS) for imaging. Confocal images were obtained using an Olympus FV1000 oil-immersion 60× objective (1.3 N.A.) with sequential-acquisition setting. Eight to ten sections were taken from top to bottom of the specimen, and brightest point projections were made.

STORM/PALM Imaging.

STORM/PALM was set up on an Olympus IX73 with a LED excitation light source containing 405-nm, 470-nm, and 590-nm excitation wavelengths. An Olympus 60× 1.3 N.A. UPlanSApo objective was used to acquire 512 × 512-pixel images using an Andor Zyla 4.2 sCMOS camera. A spinning disk was included in the emission light path to block out of focus light and retain fluorescence from a single optical plane. An IR focus lock system (zero drift correction) was used to ensure minimal drift in the z axis. Software was used to correct for XY drift in the images by using the translational setting of the StackReg plugin from ImageJ. Fluorescent 50-nm beads were used to determine the resolution of the system. As a measure of resolution, the full-with half mean of single beads were measured at ∼20 nm.

Samples were mounted on imaging buffer containing [50 mM Tris⋅base, pH 8.0, 10 mM NaCl, 10% (wt/vol) glucose, 100 mM monoethanolamine (MEA), 40 μg/mL catalase, and 0.5 mg/mL of glucose oxidase]. MEA was used as a thiol compound to facilitate photoswitching of dyes. Catalase and glucose oxidase used an oxygen scavenger system to reduce photobleaching (91). Excitation light was adjusted to 0.2–1 mW at 470 nm and 0.2–1 mW at 590 nm to acquire a sparse subset of fluorophores. Intensities of excitation light were measured at the back of the objective. Streaming acquisition of images were sequentially acquired with 10–15-ms exposure time. On average, 1,000–5,000 images were acquired for each field of view. Blinking events were identified by the change in fluorescence at individual pixel regions between frames. Images from a single focal plane were acquired. Centroid determination and image reconstruction was done by using QuickPALM (92). To determine the spatial correlation between particles in the STORM data, nearest-neighbor analysis was performed by using the Mosaic Interaction Analysis ImageJ plugin (70). In short, interaction potential between objects using spatial correlation was quantified, and the strength and scale of the interaction were quantified.

Plasmids and Transgenic Strains.

To construct fluorescent protein (FP) fusion transgenes that express in the worm coelomocyte, we used the snx-1 promoter and multisite gateway reactions to tag N or C termini. The PCR products of the genes of interest were first cloned into the Gateway entry vector pDONR221 by BP reaction (Invitrogen). Then, the pDONR221 plasmids carrying the sequences of interest were combined with psnx-1-FP or psnx-1–alone pDONR (4, 1) vector, and a FP-let-858 or unc-54–3′UTR pDONR (2, 3) vector, and recombined into the destination vector pCFJ150 [no. 19328 (93); Addgene] by using an LR clonase II plus (Invitrogen) reaction. Low-copy integrated transgenic lines for all these plasmids were obtained by the microparticle bombardment method (94, 95). GFP-tagged VPS-35 was created by using CRISPR-Cas9–mediated gene editing (96).

Membrane Fractionation.

Worms were synchronized by bleaching, cultured on nematode growth media (NGM) at 15 °C until L2/L3 stage, then shifted to 25 °C for 36 h. Young adult worms were washed off the plates with M9 buffer, pelleted, and resuspended in 500 μL of lysis buffer [20 mM Hepes, PH 8.0, 20% (wt/vol) sucrose, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitors (cat. no. 1183580001; Roche)]. The worms were then disrupted by using a Mini-Beadbeater-16 (BioSpec) with 0.5-mm Zirconia/silica beads (Bio Spec Products cat. no. 11079105z). To fully lyse the worms, five 30-s pulses with 5-min intervals on ice were used. Carcasses and nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. A total of 200 μL of the postnuclear lysate was centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 20 min and separated into pellet and soluble fractions, and then the soluble fraction was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h and again separated into soluble and pellet fractions. Pellets were reconstituted in the same volume of lysis buffer as that recovered as supernatant.

Caenorhabditis elegans Western Analysis.

Worms were synchronized and cultured on NGM plates. Fifty young adult animals of each genotype were handpicked into 10 μL of lysis buffer [100 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 8% (wt/vol) SDS, 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol] and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Extracted worm proteins were separated by 10% (wt/vol) SDS/PAGE and blotted to nitrocellulose. After blocking, the blot was probed with Caenorhabditis elegans-specific HGRS-1 antibody (80).

C. elegans Microscopy and Image Analysis.

Live worms were mounted on 10% (wt/vol) agarose pads with 0.1-µm polystyrene microspheres (no. 00876–15; Polysciences) (97). Multiwavelength fluorescence images were obtained by using an Axiovert 200M microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) equipped with a digital CCD camera (Rolera EM-C2; QImaging), captured using MetaMorph 7.7 software (Universal Imaging) and then deconvolved using AutoDeblur X3 software (AutoQuant Imaging). Colocalization analysis was done by using MetaMorph 7.7 colocalization function, whereby intensities in each channel were thresholded and average area of colocalization was analyzed. Average intensity measurements were also analyzed by MetaMorph 7.7 by using thresholded images all under the same acquisition parameters. Significance was measured by the Student t test. Citrine::HGRS-1 endosomal occupancy was imaged and analyzed blinded to genotypes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anjon Audhya and Peter McPherson for reagents, Peter Schweinsberg and Helen Ushakov for expert technical assistance, and Shaunak Kamat for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants GM067237 (to B.D.G.), GM103995 (to B.D.G.), DC15000 (to K.Y.K.), R01 NS089737 (to Q.C.), 5F32GM096599 (to A.N.), and the Arresty Center for undergraduate education (A.M., J.G., and S.W.). Some strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC), which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (Grant P40 OD010440).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. P.S.M. is a Guest Editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1612730114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Mosesson Y, Mills GB, Yarden Y. Derailed endocytosis: An emerging feature of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(11):835–850. doi: 10.1038/nrc2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seaman MN, Marcusson EG, Cereghino JL, Emr SD. Endosome to Golgi retrieval of the vacuolar protein sorting receptor, Vps10p, requires the function of the VPS29, VPS30, and VPS35 gene products. J Cell Biol. 1997;137(1):79–92. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hierro A, et al. Functional architecture of the retromer cargo-recognition complex. Nature. 2007;449(7165):1063–1067. doi: 10.1038/nature06216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arighi CN, Hartnell LM, Aguilar RC, Haft CR, Bonifacino JS. Role of the mammalian retromer in sorting of the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor. J Cell Biol. 2004;165(1):123–133. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swarbrick JD, et al. VPS29 is not an active metallo-phosphatase but is a rigid scaffold required for retromer interaction with accessory proteins. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e20420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harbour ME, Seaman MN. Evolutionary variations of VPS29, and their implications for the heteropentameric model of retromer. Commun Integr Biol. 2011;4(5):619–622. doi: 10.4161/cib.4.5.16855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harterink M, et al. A SNX3-dependent retromer pathway mediates retrograde transport of the Wnt sorting receptor Wntless and is required for Wnt secretion. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(8):914–923. doi: 10.1038/ncb2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horazdovsky BF, et al. A sorting nexin-1 homologue, Vps5p, forms a complex with Vps17p and is required for recycling the vacuolar protein-sorting receptor. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8(8):1529–1541. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.8.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu TT, Gomez TS, Sackey BK, Billadeau DD, Burd CG. Rab GTPase regulation of retromer-mediated cargo export during endosome maturation. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23(13):2505–2515. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-11-0915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wassmer T, et al. A loss-of-function screen reveals SNX5 and SNX6 as potential components of the mammalian retromer. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(pt 1):45–54. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu N, Shen Q, Mahoney TR, Liu X, Zhou Z. Three sorting nexins drive the degradation of apoptotic cells in response to PtdIns(3)P signaling. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22(3):354–374. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e10-09-0756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlton J, et al. Sorting nexin-1 mediates tubular endosome-to-TGN transport through coincidence sensing of high- curvature membranes and 3-phosphoinositides. Curr Biol. 2004;14(20):1791–1800. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Weering JR, et al. Molecular basis for SNX-BAR-mediated assembly of distinct endosomal sorting tubules. EMBO J. 2012;31(23):4466–4480. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burd C, Cullen PJ. Retromer: A master conductor of endosome sorting. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(2):a016774. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGough IJ, Cullen PJ. Recent advances in retromer biology. Traffic. 2011;12(8):963–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi A, et al. Regulation of endosomal clathrin and retromer-mediated endosome to Golgi retrograde transport by the J-domain protein RME-8. EMBO J. 2009;28(21):3290–3302. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popoff V, et al. Analysis of articulation between clathrin and retromer in retrograde sorting on early endosomes. Traffic. 2009;10(12):1868–1880. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujibayashi A, et al. Human RME-8 is involved in membrane trafficking through early endosomes. Cell Struct Funct. 2008;33(1):35–50. doi: 10.1247/csf.07045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Grant B, Hirsh D. RME-8, a conserved J-domain protein, is required for endocytosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12(7):2011–2021. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.7.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walsh P, Bursać D, Law YC, Cyr D, Lithgow T. The J-protein family: Modulating protein assembly, disassembly and translocation. EMBO Rep. 2004;5(6):567–571. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ungewickell E, et al. Role of auxilin in uncoating clathrin-coated vesicles. Nature. 1995;378(6557):632–635. doi: 10.1038/378632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greener T, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans auxilin: A J-domain protein essential for clathrin-mediated endocytosis in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(2):215–219. doi: 10.1038/35055137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xhabija B, Vacratsis PO. Receptor-mediated endocytosis 8 utilizes an N-terminal phosphoinositide-binding motif to regulate endosomal clathrin dynamics. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(35):21676–21689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.644757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman CL, Hesketh G, Seaman MN. RME-8 coordinates the activity of the WASH complex with the function of the retromer SNX dimer to control endosomal tubulation. J Cell Sci. 2014;127(pt 9):2053–2070. doi: 10.1242/jcs.144659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurley JH. The ESCRT complexes. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;45(6):463–487. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2010.502516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Babst M. MVB vesicle formation: ESCRT-dependent, ESCRT-independent and everything in between. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23(4):452–457. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henne WM, Buchkovich NJ, Emr SD. The ESCRT pathway. Dev Cell. 2011;21(1):77–91. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polo S, et al. A single motif responsible for ubiquitin recognition and monoubiquitination in endocytic proteins. Nature. 2002;416(6879):451–455. doi: 10.1038/416451a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bishop N, Horman A, Woodman P. Mammalian class E vps proteins recognize ubiquitin and act in the removal of endosomal protein-ubiquitin conjugates. J Cell Biol. 2002;157(1):91–101. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofmann K, Falquet L. A ubiquitin-interacting motif conserved in components of the proteasomal and lysosomal protein degradation systems. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26(6):347–350. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01835-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raiborg C, Stenmark H. Hrs and endocytic sorting of ubiquitinated membrane proteins. Cell Struct Funct. 2002;27(6):403–408. doi: 10.1247/csf.27.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raiborg C, et al. Hrs sorts ubiquitinated proteins into clathrin-coated microdomains of early endosomes. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(5):394–398. doi: 10.1038/ncb791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raiborg C, et al. FYVE and coiled-coil domains determine the specific localisation of Hrs to early endosomes. J Cell Sci. 2001;114(pt 12):2255–2263. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.12.2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sönnichsen B, De Renzis S, Nielsen E, Rietdorf J, Zerial M. Distinct membrane domains on endosomes in the recycling pathway visualized by multicolor imaging of Rab4, Rab5, and Rab11. J Cell Biol. 2000;149(4):901–914. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.4.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sachse M, Urbé S, Oorschot V, Strous GJ, Klumperman J. Bilayered clathrin coats on endosomal vacuoles are involved in protein sorting toward lysosomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(4):1313–1328. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-10-0525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dinneen JL, Ceresa BP. Continual expression of Rab5(Q79L) causes a ligand-independent EGFR internalization and diminishes EGFR activity. Traffic. 2004;5(8):606–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9219.2004.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gulappa T, Clouser CL, Menon KM. The role of Rab5a GTPase in endocytosis and post-endocytic trafficking of the hCG-human luteinizing hormone receptor complex. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68(16):2785–2795. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0594-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stenmark H, et al. Inhibition of rab5 GTPase activity stimulates membrane fusion in endocytosis. EMBO J. 1994;13(6):1287–1296. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen CC-H, et al. RAB-10 is required for endocytic recycling in the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(3):1286–1297. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato M, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans SNAP-29 is required for organellar integrity of the endomembrane system and general exocytosis in intestinal epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22(14):2579–2587. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-04-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gu M, et al. AP2 hemicomplexes contribute independently to synaptic vesicle endocytosis. eLife. 2013;2:e00190. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waguri S, et al. Visualization of TGN to endosome trafficking through fluorescently labeled MPR and AP-1 in living cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14(1):142–155. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-06-0338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghosh RN, Mallet WG, Soe TT, McGraw TE, Maxfield FR. An endocytosed TGN38 chimeric protein is delivered to the TGN after trafficking through the endocytic recycling compartment in CHO cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;142(4):923–936. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.4.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bai Z, Grant BD. A TOCA/CDC-42/PAR/WAVE functional module required for retrograde endocytic recycling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(12):E1443–E1452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418651112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Belenkaya TY, et al. The retromer complex influences Wnt secretion by recycling wntless from endosomes to the trans-Golgi network. Dev Cell. 2008;14(1):120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Franch-Marro X, et al. Wingless secretion requires endosome-to-Golgi retrieval of Wntless/Evi/Sprinter by the retromer complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(2):170–177. doi: 10.1038/ncb1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pan CL, et al. C. elegans AP-2 and retromer control Wnt signaling by regulating mig-14/Wntless. Dev Cell. 2008;14(1):132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang PT, et al. Wnt signaling requires retromer-dependent recycling of MIG-14/Wntless in Wnt-producing cells. Dev Cell. 2008;14(1):140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Port F, et al. Wingless secretion promotes and requires retromer-dependent cycling of Wntless. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(2):178–185. doi: 10.1038/ncb1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seaman MN. Cargo-selective endosomal sorting for retrieval to the Golgi requires retromer. J Cell Biol. 2004;165(1):111–122. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin SX, Grant B, Hirsh D, Maxfield FR. Rme-1 regulates the distribution and function of the endocytic recycling compartment in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(6):567–572. doi: 10.1038/35078543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lieu ZZ, Gleeson PA. Identification of different itineraries and retromer components for endosome-to-Golgi transport of TGN38 and Shiga toxin. Eur J Cell Biol. 2010;89(5):379–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rojas R, Kametaka S, Haft CR, Bonifacino JS. Interchangeable but essential functions of SNX1 and SNX2 in the association of retromer with endosomes and the trafficking of mannose 6-phosphate receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(3):1112–1124. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00156-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raiborg C, Bache KG, Mehlum A, Stang E, Stenmark H. Hrs recruits clathrin to early endosomes. EMBO J. 2001;20(17):5008–5021. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.5008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chin LS, Raynor MC, Wei X, Chen HQ, Li L. Hrs interacts with sorting nexin 1 and regulates degradation of epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(10):7069–7078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004129200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sato K, Norris A, Sato M, Grant BD. C. elegans as a model for membrane traffic. WormBook. 2014;Apr 25:1–47. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.77.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fares H, Greenwald I. Genetic analysis of endocytosis in Caenorhabditis elegans: Coelomocyte uptake defective mutants. Genetics. 2001;159(1):133–145. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fares H, Greenwald I. Regulation of endocytosis by CUP-5, the Caenorhabditis elegans mucolipin-1 homolog. Nat Genet. 2001;28(1):64–68. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nicot AS, et al. The phosphoinositide kinase PIKfyve/Fab1p regulates terminal lysosome maturation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(7):3062–3074. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-12-1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsai J, Douglas MG. A conserved HPD sequence of the J-domain is necessary for YDJ1 stimulation of Hsp70 ATPase activity at a site distinct from substrate binding. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(16):9347–9354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cheetham ME, Caplan AJ. Structure, function and evolution of DnaJ: Conservation and adaptation of chaperone function. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1998;3(1):28–36. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1998)003<0028:sfaeod>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yan W, Craig EA. The glycine-phenylalanine-rich region determines the specificity of the yeast Hsp40 Sis1. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(11):7751–7758. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sato K, et al. Differential requirements for clathrin in receptor-mediated endocytosis and maintenance of synaptic vesicle pools. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(4):1139–1144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809541106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Raiborg C, et al. Hrs sorts ubiquitinated proteins into clathrin-coated microdomains of early endosomes. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(5):394–398. doi: 10.1038/ncb791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Raiborg C, Wesche J, Malerød L, Stenmark H. Flat clathrin coats on endosomes mediate degradative protein sorting by scaffolding Hrs in dynamic microdomains. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2414–2424. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gleason RJ, Akintobi AM, Grant BD, Padgett RW. BMP signaling requires retromer-dependent recycling of the type I receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(7):2578–2583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319947111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McGough IJ, Cullen PJ. Clathrin is not required for SNX-BAR-retromer-mediated carrier formation. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(pt 1):45–52. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van de Linde S, et al. Direct stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy with standard fluorescent probes. Nat Protoc. 2011;6(7):991–1009. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Helmuth JA, Paul G, Sbalzarini IF. Beyond co-localization: Inferring spatial interactions between sub-cellular structures from microscopy images. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:372. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shivanandan A, Radenovic A, Sbalzarini IF. MosaicIA: An ImageJ/Fiji plugin for spatial pattern and interaction analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:349. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gruenberg J. The endocytic pathway: A mosaic of domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(10):721–730. doi: 10.1038/35096054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Puthenveedu MA, et al. Sequence-dependent sorting of recycling proteins by actin-stabilized endosomal microdomains. Cell. 2010;143(5):761–773. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hunt SD, Townley AK, Danson CM, Cullen PJ, Stephens DJ. Microtubule motors mediate endosomal sorting by maintaining functional domain organization. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(pt 11):2493–2501. doi: 10.1242/jcs.122317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Louvard D, et al. A monoclonal antibody to the heavy chain of clathrin. EMBO J. 1983;2(10):1655–1664. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01640.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Raposo G, Tenza D, Murphy DM, Berson JF, Marks MS. Distinct protein sorting and localization to premelanosomes, melanosomes, and lysosomes in pigmented melanocytic cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;152(4):809–824. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.van Meel E, Klumperman J. TGN exit of the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor does not require acid hydrolase binding. Cell Logist. 2014;4(3):e954441. doi: 10.4161/21592780.2014.954441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Klumperman J, Raposo G. The complex ultrastructure of the endolysosomal system. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(10):a016857. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Raiborg C. Hrs makes receptors silent: A key to endosomal protein sorting. Crit Rev Oncog. 2006;12(3-4):295–discussion 295–296. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v12.i3-4.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van Niel G, et al. The tetraspanin CD63 regulates ESCRT-independent and -dependent endosomal sorting during melanogenesis. Dev Cell. 2011;21(4):708–721. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mayers JR, et al. ESCRT-0 assembles as a heterotetrameric complex on membranes and binds multiple ubiquitinylated cargoes simultaneously. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(11):9636–9645. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.185363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Derivery E, Helfer E, Henriot V, Gautreau A. Actin polymerization controls the organization of WASH domains at the surface of endosomes. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Derivery E, Gautreau A. Quantitative analysis of endosome tubulation and microdomain organization mediated by the WASH complex. Methods Cell Biol. 2015;130:215–234. doi: 10.1016/bs.mcb.2015.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chang HC, Hull M, Mellman I. The J-domain protein Rme-8 interacts with Hsc70 to control clathrin-dependent endocytosis in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 2004;164(7):1055–1064. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Girard M, McPherson PS. RME-8 regulates trafficking of the epidermal growth factor receptor. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(6):961–966. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Girard M, Poupon V, Blondeau F, McPherson PS. The DnaJ-domain protein RME-8 functions in endosomal trafficking. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(48):40135–40143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Raiborg C, Wesche J, Malerød L, Stenmark H. Flat clathrin coats on endosomes mediate degradative protein sorting by scaffolding Hrs in dynamic microdomains. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(pt 12):2414–2424. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Seaman MNJ, Freeman CL. Analysis of the Retromer complex-WASH complex interaction illuminates new avenues to explore in Parkinson disease. Commun Integr Bio l. 2014;7:e29483. doi: 10.4161/cib.29483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77(1):71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Timmons L, Fire A. Specific interference by ingested dsRNA. Nature. 1998;395(6705):854. doi: 10.1038/27579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kamath RS, Ahringer J. Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods. 2003;30(4):313–321. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dempsey GT, Vaughan JC, Chen KH, Bates M, Zhuang X. Evaluation of fluorophores for optimal performance in localization-based super-resolution imaging. Nat Methods. 2011;8(12):1027–1036. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Henriques R, et al. QuickPALM: 3D real-time photoactivation nanoscopy image processing in ImageJ. Nat Methods. 2010;7(5):339–340. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0510-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Frøkjaer-Jensen C, et al. Single-copy insertion of transgenes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Genet. 2008;40(11):1375–1383. doi: 10.1038/ng.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Praitis V, Casey E, Collar D, Austin J. Creation of low-copy integrated transgenic lines in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2001;157(3):1217–1226. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.3.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schweinsberg PJ, Grant BD. C. elegans gene transformation by microparticle bombardment. WormBook. Dec 30:1–10. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.166.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dickinson DJ, Ward JD, Reiner DJ, Goldstein B. Engineering the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using Cas9-triggered homologous recombination. Nat Methods. 2013;10(10):1028–1034. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim E, Sun L, Gabel CV, Fang-Yen C. Long-term imaging of Caenorhabditis elegans using nanoparticle-mediated immobilization. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]