Significance

There are different views about the targets of regenerative therapies to induce functional recovery in patients with motor paralysis following brain and spinal cord injury: whether we should aim at repairing the injured corticospinal tract or at facilitating compensation by other descending motor pathways. To help answer this question, we used double viral vectors to reversibly and selectively block the propriospinal neurons (PNs), one of the major intercalated neurons mediating cortical commands to motoneurons, in monkeys with partial spinal cord injury. We demonstrated causal roles of the PN-mediated pathway in promoting recovery of hand dexterity after the lesion. Thus, targeting the PNs might lead to developing effective treatment to facilitate recovery after spinal cord injury.

Keywords: spinal cord injury, plasticity, neural circuit, nonhuman primates, viral vector

Abstract

The direct cortico-motoneuronal connection is believed to be essential for the control of dexterous hand movements, such as precision grip in primates. It was reported, however, that even after lesion of the corticospinal tract (CST) at the C4–C5 segment, precision grip largely recovered within 1–3 mo, suggesting that the recovery depends on transmission through intercalated neurons rostral to the lesion, such as the propriospinal neurons (PNs) in the midcervical segments. To obtain direct evidence for the contribution of PNs to recovery after CST lesion, we applied a pathway-selective and reversible blocking method using double viral vectors to the PNs in six monkeys after CST lesions at C4–C5. In four monkeys that showed nearly full or partial recovery, transient blockade of PN transmission after recovery caused partial impairment of precision grip. In the other two monkeys, CST lesions were made under continuous blockade of PN transmission that outlasted the entire period of postoperative observation (3–4.5 mo). In these monkeys, precision grip recovery was not achieved. These results provide evidence for causal contribution of the PNs to recovery of hand dexterity after CST lesions; PN transmission is necessary for promoting the initial stage recovery; however, their contribution is only partial once the recovery is achieved.

As a potential treatment for brain and spinal cord injury, regeneration of the injured axons has been attempted in animal models, often using rodents with corticospinal tract (CST) lesions. Regeneration of the injured CST fibers was facilitated by treatments such as peripheral nerve graft (1), application of an antibody against neurite growth inhibitors IN-1 (2), combined application of the antibody and neurotrophic factor NT-3 (3), and transplantation of neural stem cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (4). A more recent study showed that regenerated CST axons increased the connection to the spinal motoneurons (MNs) after spinal cord injury in monkeys (5). However, in these studies, the causal contribution of such regenerated fibers to the functional recovery was not directly demonstrated. Therefore, recent debates address the question whether these therapies should target repairing the injured CST fibers and/or facilitating compensation by indirect cortico-motoneuronal (CM) connections via other descending motor pathways (6–9).

Traditionally, the neural control of dexterous hand movements in higher primates has primarily been associated with development of the direct pathway from the motor cortex to MNs, known as the CM pathway (10–12). Lesion of the CST at the brainstem level in nonhuman primates caused near-permanent loss of dexterous hand movements (13). The authors also argued for partial compensation of grasping movements by the brainstem-mediated descending pathways such as the rubrospinal tract (14). More recent studies on the neural basis of functional recovery following CST lesions revealed that a variety of plastic changes in neural circuits occurred in the supraspinal structures including the motor and premotor cortices (15), and in the connectivity from the nucleus accumbens to motor cortex (16, 17). At the more caudal level, sprouting of the midline-crossing CST fibers was revealed in the lower cervical segment of monkeys with hemisected spinal cords (18). In addition, the “indirect” CM pathways via interneurons such as the propriospinal neurons (PNs), which are located in the midcervical segments and project to hand/arm MNs in the lower cervical segments, and/or reticulospinal neurons (RSNs) in the pontomedullary reticular formation might also be involved in mediating cortical commands to MNs of forelimb muscles in animal models with CST lesions (19–21). To demonstrate which pathways causally contribute to recovery after damage to the CST, selective and reversible manipulation of particular pathways is needed.

Historically, much less attention has been paid to the “indirect” CM pathways in the control of dexterous hand movements compared with the direct CM pathway, because they were supposed not to be involved in the control of fine digit movements. During the last decade, however, lesion and electrophysiological studies in nonhuman primates suggested that the pathway through the PNs might be involved in the control of dexterous hand movements in the intact state (21, 22). However, this suggestion was based on the indirect evidence obtained by comparing the behavioral effects caused by transection of the CST at different rostrocaudal levels. Recently, however, a technique was developed that can selectively and reversibly control transmission via neurons comprising a particular pathway using two different kinds of viral vectors and doxycycline (Dox)-inducible tetanus neurotoxin. Applying the technique to the PNs in intact monkeys revealed that the PN-mediated pathway could carry the command for dexterous hand movements in the intact state (23). However, contribution of the PN-mediated pathway to recovery after lesion of the direct CM pathway in the monkey remains unclear. In the present study, to examine whether the PNs causally contribute to recovery of dexterous hand movements after damage to the CST, we applied the pathway-selective and reversible blocking method to the PNs in monkeys after lesioning the CST at C4–C5.

Results

The experiments were conducted on six macaque monkeys (4.0–6.0 y, 4.0–8.3 kg; see details in Table S1). Two kinds of viral vectors were injected into the cervical spinal cord of each monkey (Fig. 1A). The first was a highly efficient retrograde gene transfer vector, HiRet (24) or its derivatives [FuG-E (25) or NeuRet (26)], carrying the sequences for tetracycline-inducible, enhanced GFP (EGFP)-tagged enhanced tetanus neurotoxin light chain (eTeNT) (27). This vector was injected into the ventral horn of the C6–Th1 segments, where MNs innervating distal forelimb muscles are located. The second was the adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector carrying the sequence for the highly efficient Tet-on, rtTAV16. This vector was injected into the intermediate zone of the caudal C2 to caudal C4 segment, where the cell bodies of PNs are located, thus enabling the Dox-inducible blockade of PNs (23). CST lesions were then made between the injection sites of the two viral vectors, mostly in C4–C5 (Fig. 1 A and B). Two different sets of protocols for administering Dox were arranged (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1) to determine whether and how the PNs contributed to recovery of dexterous hand movements after the lesion, as described below. At the end of the behavioral observation, acute electrophysiological experiments were conducted under anesthesia to confirm the extent of the lesion and the effects of blockade of PNs by the vectors.

Table S1.

Backgrounds of monkeys and the extent of lesions

| Monkeys | Species | Sex | Age, y | BW, kg | Lesion extent, % | Lesion sites |

| U | M. fuscata | F | 5.1 | 4.8 | 51.6 | C4–C5 |

| B | M. fuscata | M | 6.0 | 8.3 | 42.5 | C4–C5 |

| S | M. fuscata | F | 5.3 | 5.9 | 70.4 | C4–C5 |

| N | M. fuscata | F | 4.4 | 6.0 | 43.0 | C6/C7 |

| K | M. fuscata | F | 4.0 | 4.4 | 61.5 | C4–C5 |

| R | M. fuscata | F | 4.8 | 4.0 | 54.5 | C4–C5 |

BW, body weight; F, female; M, male; M. fuscata, Macaca fuscata.

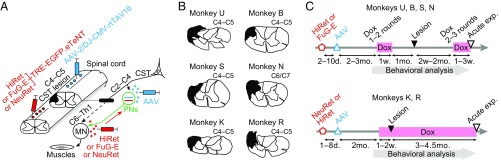

Fig. 1.

Experimental procedures and the extent of lesions in all of the six monkeys. (A) We injected a retrograde gene transfer vector, HiRet/FuG-E/NeuRet-TRE-EGFP.eTeNT, into C6 to Th1 and successively injected an anterograde vector, AAV-2/DJ-CMV-rtTAV16, into caudal C2 to caudal C4, that enabled doxycycline (Dox)-inducible blockade of propriospinal neurons (PNs) in the midcervical segments (23). The lateral corticospinal tract (CST) was then lesioned between the injection sites of the two viral vectors, mostly in C4–C5 (Left, in black; Right, black bar). MN, motoneurons. (B) Lesions are indicated by black areas. (C) Two different sets of protocols for administering Dox (pink bars) were arranged. In the transient–PN-blocked group (monkeys U, B, S, and N), 2–3 mo after the viral injections (HiRet or FuG-E, red open pentagon, and AAV, blue open triangle), administration of Dox for 1–3 wk was repeated one to three times before and after the lesion (black filled triangle). In the continuously PN-blocked group (monkeys K and R), 2 mo after the viral injections (NeuRet or HiRet, red open pentagon, and AAV, blue open triangle), administration of Dox from 1 to 2 wk before lesion continued for 3–4.5 mo after the lesion. Black open triangles, terminal acute electrophysiological experiments.

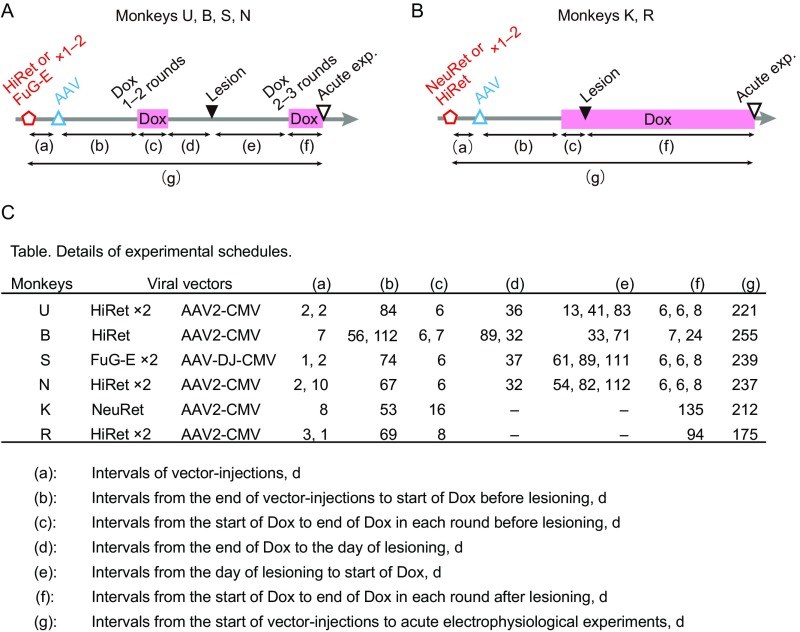

Fig. S1.

Details of experimental schedules. (A) Experimental time course of monkeys U, B, S, and N, and (B) that of monkeys K and R. Red open pentagons, injection of HiRet or FuG-E or NeuRet. Blue open triangles, injection of AAV. Pink bars, administrations of Dox. Black filled triangles, lesioning of the CST. Black open triangles, terminal acute electrophysiological experiments. Intervals of the events were defined as (a)–(g). (C) Table of details of experimental schedules.

Confirmation of the Extent and Completeness of Lesion.

The dorsolateral funiculus was lesioned unilaterally at the C4–C5 segment to completely interrupt the direct CM transmission (15, 17, 19, 21, 28, 29), while sparing the axons of the PNs and RSNs. In the present study, five of the six monkeys had a lesion in C4–C5 (monkeys U, B, S, K, and R), whereas the lesion of monkey N was located in C6/C7 (Fig. 1B and Table S1). The extent of the lesions was 42.5−70.4% of the whole lateral and ventral funiculi (SI Materials and Methods and Table S1). In monkeys S and N, the lesions partly extended to the dorsal column. Completeness of the lesion was examined electrophysiologically by recording the cord dorsum potentials at C6 and extracellular field potentials in the deep radial motor nuclei at C6−C7, that is, caudal to the CST lesion, evoked by stimulation of the contralateral pyramid (Fig. 2G). No direct volleys or monosynaptic negative field potentials were found in the affected side, which was the side with the viral vector injections and a chronic spinal cord injury, in any of the monkeys examined (a representative is shown in Fig. 2H), revealing that the lesions completely abolished the direct CM connections.

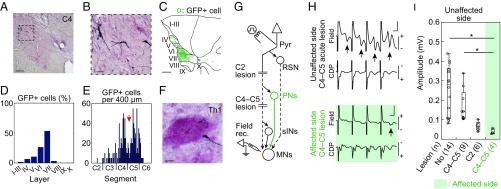

Fig. 2.

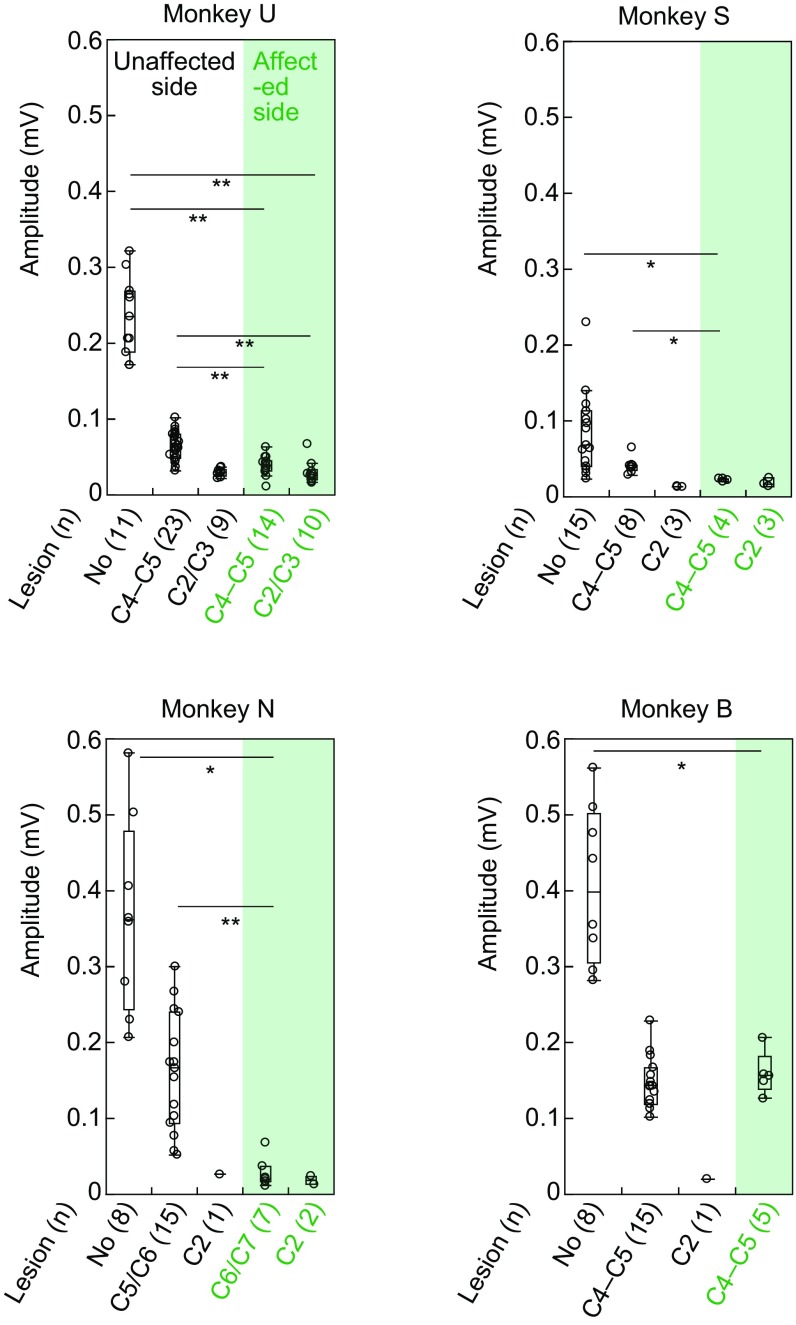

Visualization of blocked PNs and confirmation of blockade of synaptic transmission through PNs. A–F were obtained from monkey U, and G–I were obtained from monkey K. (A) Representative GFP-labeled cells in C4. Dashed square indicates area shown in B. (Scale bar, 200 μm.) (B) High magnification of A. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (C) Reconstructed distribution of GFP-labeled cells by multiple sections, which were separated by 200 μm. I–X, laminae of Rexed. (Scale bar, 500 μm.) (D) Distribution of GFP-labeled cells in individual laminae (I–X). (E) Longitudinal distribution of GFP-labeled cells along the spinal cord. Red arrow indicates the site of lesion. (F) A representative axon and bouton of GFP-labeled cell in a motor nucleus at Th1. The sections were counterstained with Neutral Red. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (G) The arrangement of terminal acute electrophysiological experiments. In addition to the direct cortico-motoneuronal connection, indirect pathways through reticulospinal neurons (RSN), propriospinal neurons (PNs), and segmental interneurons (sINs) might exist. During the experiments, the lateral CST was transected at C4–C5 and successively at C2. MNs, motoneurons. Pyr, contralateral medullary pyramid. (H) Representative field potentials (Field) and cord dorsum potentials (CDP) in the unaffected side of a monkey with a C4–C5 acute lesion (Top) and in the affected side (Bottom) following four trained stimuli of Pyr at 200 μA. Arrows indicate disynaptic field potentials. (Vertical scale bar, 0.2 mV; horizontal bar, 1 ms.) (I) Quantitative analysis of the amplitudes of the disynaptic field potentials with no lesion, a C4–C5 lesion, and a C2 lesion on the unaffected side, and with a C4–C5 lesion on the affected side. The numbers of records are shown in parentheses. The box plots represent the 25th and 75th percentiles of the data. *P < 0.01 (the Wilcoxon test).

Visualization of “Blocked” PNs.

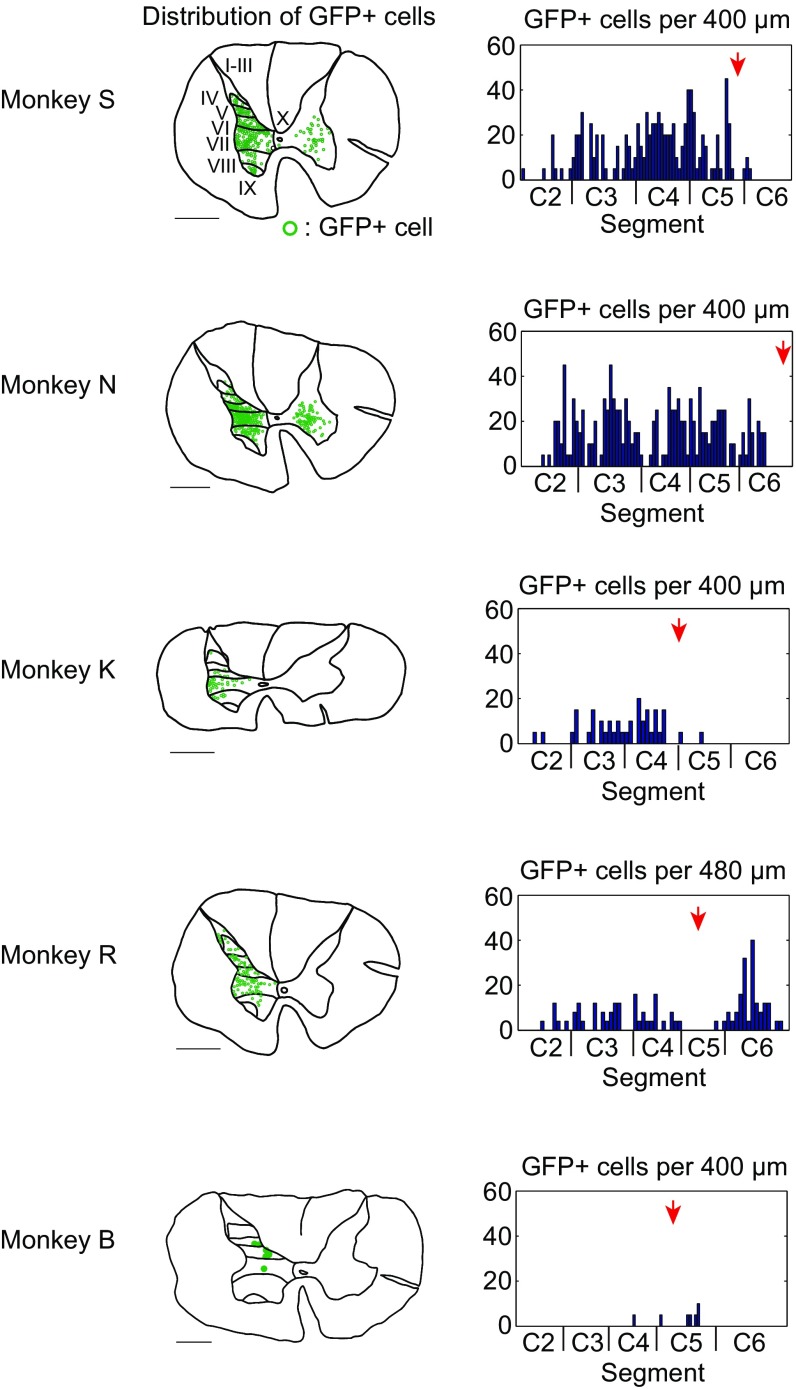

The double-infected PNs were visualized with anti-GFP immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2 A–F and Fig. S2) (23). Labeled cell bodies were located mainly in the lateral portions of laminae VI−VII of Rexed (Fig. 2 A–D and Fig. S2), that is, the intermediate zone where PNs are known to be located (30). Their longitudinal distribution extended from C2 to the rostral part of C6 (Fig. 2E and Fig. S2). As described above, the CST lesion was located mainly in C4–C5. Therefore, some GFP-labeled cells were located caudal to the lesion in two monkeys (U and R), presumably due to spread of the vector solution beyond lesion sites. However, we consider that this would not affect the main conclusion of this study (Discussion). Axons and boutons of GFP-labeled cells were found in the motor nuclei at C6–Th1 (Fig. 2F), suggesting that the blocked cells were directly connected with MNs innervating distal forelimb muscles.

Fig. S2.

Distribution of GFP-labeled cells in other monkeys (S, N, K, R, and B). Reconstructed layer distribution and longitudinal distribution of GFP-labeled cells. I–X, laminae of Rexed. (Scale bar, 1 mm.) Red arrows indicate the sites of lesions.

Confirmation of Blockade of Synaptic Transmission Through PNs.

We examined to what degree the PN-mediated cortical commands to MNs were blocked by the administration of Dox by recording extracellular field potentials in many locations of the deep radial motor nuclei, each separated by more than 200 μm, in response to stimulation of the contralateral pyramid (Fig. 2G) under anesthesia. To dissociate effects of the PN-mediated pathway from other indirect pathways that could mediate the cortical commands to MNs, such as those through segmental interneurons (sINs) and RSNs, the lesions of the dorsolateral funiculus were made sequentially at the C4–C5 level on the unaffected side and then at the C2 levels on both sides during the acute experiments (Fig. 2G). Strychnine was injected i.v. to reduce glycinergic inhibition from the CST. The amplitudes of the disynaptic field potentials in the affected side were significantly smaller than those in the unaffected side after acute C4–C5 CST lesion on the unaffected side (Fig. 2 H and I, and Fig. S3), suggesting that synaptic transmission through the propriospinal and reticulospinal pathways in the affected side were much weaker compared with those in the unaffected side. After additional C2 CST lesion on the unaffected side (Fig. 2I and Fig. S3) and on the affected side (Fig. S3), the amplitudes were very small, suggesting that contribution of the reticulospinal pathway was minor in both sides. These findings revealed that synaptic transmission presumably through the PNs was blocked by 74.2–93.3% [mean (SD), 83.1 (8.2)] compared with the unaffected side in four monkeys (U, S, N, and K), whereas no significant blocking was observed in monkey B, as will be discussed later. No data were obtained from monkey R due to a sudden change in the monkey’s condition during the experiment.

Fig. S3.

Quantitative analysis of the amplitudes of the disynaptic field potentials compared between the unaffected side and affected side in monkeys U, S, N, and B. Bottom row indicates lesion sites and the numbers of records are in parentheses. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001 (the Wilcoxon test).

Partially Impaired Recovery of Dexterous Hand Movements After the CST Lesion by Transient Blockade of PNs.

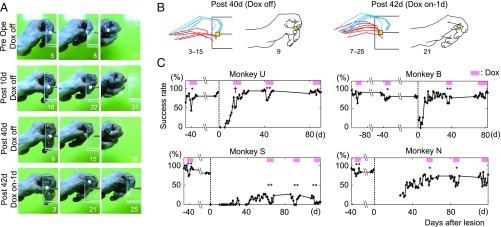

We conducted behavioral observations of recovery time courses after the CST lesions using a reach and grasp task (Fig. 3 and Movies S1–S4). The monkeys were trained to reach for and grasp a piece of sweet potato presented on the other side of a slit (8- to 10-mm width) with a precision grip, which was defined as a grip using just the index finger and the pad of thumb (the first and third rows of Fig. 3A, the Left of Fig. 3B, the first row of Fig. 4A, the Left of Fig. 4B, and Movies S1 and S3). Before lesion, administration of Dox partly and transiently impaired these dexterous hand movements, such as precision grip, correctness of gripping, and reaching, consistent with a previous study (23). During administering Dox, success rate (SI Materials and Methods, Behavioral Testing) dropped by 15.8–34.1% in transiently PN-blocked monkeys (U, B, S, and N). One to 2 mo after lesion, administration of Dox impaired dexterous hand movements that had already shown recovery, for instance, in cooperative movements of the index finger and thumb (Fig. 3 A and B, and Movies S1–S4). Decreased success rates generally tended to start 1–2 d after the start of Dox administration and returned to baseline levels within 1 wk, even after lesion, suggesting a limited role of PNs in dexterous hand movements in the intact and once-recovered state. Recovery time courses differed between the following two groups. In the well-recovered group, including monkeys U and B, dexterous hand movements recovered within less than 1 mo after the lesion. On the other hand, in the partial-recovery group (monkeys S and N), there was no full recovery during the entire observation period even through intensive rehabilitative training, probably because of the lesion in C6/C7 (monkey N, Fig. 1B, and Table S1) and extended lesions to the dorsal column (monkeys S and N, Fig. 1B) (31) and/or to the ventral part of the lateral funiculus (monkey S; the extent of lesion was 70.4%; Fig. 1B and Table S1). Despite different recovery time courses in these two groups, success rates for recovered or partially recovered dexterous hand movements decreased significantly during Dox administration 1–2 mo after lesion (success rates dropped by 19.1–24.1% in the four monkeys). These results provided evidence for partial, but causal contribution of the PNs to recovery of dexterous hand movements after the CST lesion. In contrast, the effects of Dox administration 2–3 mo after lesion differed between the two groups; in the well-recovered group (monkeys U and B), no significant decrease in success rates were observed during administration of Dox 71–87 d after lesion, whereas in the partial-recovery group (monkeys S and N), success rates were still significantly decreased 82–92 d after lesion. These findings suggest that PNs contribute to recovery in different ways depending on the stage of recovery, which might vary depending on the severity of the lesions. It is worth remembering that electrophysiological analysis indicated that neurotransmission through the PNs was not obviously blocked in monkey B (Fig. S3). In this monkey, the behavioral effects of Dox were relatively weak, likely due to low infection and/or expression rate of the viral vectors, as the number of GFP-labeled cells was small (Fig. S2). It was also supposed that expression of eTeNT might have deteriorated during the long survival time after the viral vector injection (255 d; see table in Fig. S1).

Fig. 3.

Behavioral effects following transient blockade of PNs after the CST lesion. (A) Recovery process of dexterous hand movements 10 and 40 d after the CST lesion and a typical example obtained 42 d after the lesion (1 d after start of Dox) in monkey U. The numbers below in each panel indicate frame numbers (30 frames/s) from the moment when the digit passed through the edge of slit. (B) Stick diagram and drawing of grasping movements of monkey U. Blue line, the index finger and estimated second metacarpal. Red line, the thumb and estimated first metacarpal. Every third frame before and after the time of touching a piece of food to just before pulling it out in a single trial are superimposed at 40 d (Dox-off) and at 42 d (Dox-on, 1 d after start of Dox) after lesion. The numbers below indicate frame numbers from the moment when the digit passed through the edge of slit. (C) Recovery curves of success rate for dexterous hand movements (SI Materials and Methods, Behavioral Testing) after lesion in four monkeys (U, B, S, and N). The data are aligned to the day of lesion (dashed line). Pink bars, administration of Dox. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (comparison of total success rate for 4 d before and after Dox using the Pearson χ2 test). †P < 0.05 (comparison of total success rate for 2 d before and after Dox using the Pearson χ2 test).

Fig. 4.

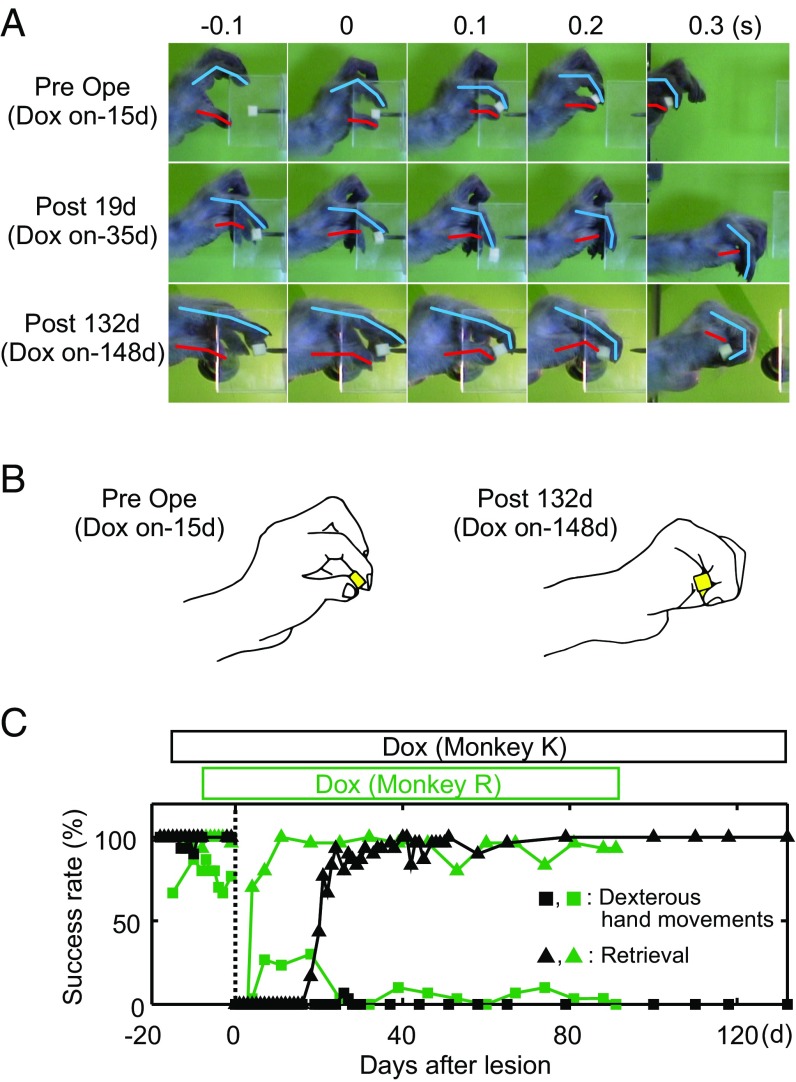

Behavioral effects under continuous blockade of PNs after the CST lesion. (A) Recovery process of dexterous hand movements under continuous administration of Dox in monkey K. Upper row, before lesion (15 d after start of Dox). Middle row, 19 d after lesion (35 d after start of Dox). Bottom row, 132 d after lesion (148 d after start of Dox). Each panel is aligned to the moment of touching a piece of food. Blue line, the index finger; red line, the thumb. (B) Drawing of shapes of grasping before (15 d after start of Dox) and 132 d after lesion (148 d after start of Dox) in monkey K. (C) Recovery curves of success rates for dexterous hand movements (squares) and retrieval (triangles) under continuous administration of Dox (open boxes above the curves) after the lesion in monkey K (black lines) and monkey R (green lines). The data are aligned to the day of lesion (dashed line).

Impairment of Recovery Under Continuous Blockade of PNs.

In monkeys K and R, Dox was administrated continuously to suppress PNs over the entire time course of recovery after the lesion. These monkeys could not perform the precision grip (Fig. 4C, squares) but could retrieve a small piece of food without dropping it, which we termed a “retrieval,” in most cases by gripping it with the dorsum of the thumb or palm (Fig. 4B, Right). Successful retrievals with the alternate grips persisted throughout the entire period of observation (91–132 d after the lesion) (Fig. 4 A and B, Right, and Fig. 4C, triangles). Thus, in both of these monkeys, continuous blockade of PNs from 1 to 2 wk before lesion resulted in minimum recovery of dexterous hand movements 3–4.5 mo after lesion (Fig. 4C), despite the intensive rehabilitative training required during the early period after the lesion (29). These findings contrasted obviously with those of previous studies, in which dexterous hand movements of all monkeys with C4–C5 CST lesions of this size largely recovered within 1–3 mo (15, 17, 21, 28). These findings suggested that the PNs played a key role in promoting the recovery of dexterous hand movements after the CST lesion.

SI Materials and Methods

Preparation of Viral Vectors.

The preparation of viral vectors, HiRet-TRE-EGFP.eTeNT, NeuRet-TRE-EGFP.eTeNT, and AAV-2-CMV-rtTAV16, were described by Kinoshita et al. (23) and Sooksawate et al. (46). We also added the new vectors, FuG-E-TRE-EGFP.eTeNT and AAV-DJ-CMV-rtTAV16.

FuG-E-TRE-EGFP.eTeNT.

This vector was modified from a previously reported version of the HIV type 1 (HIV-1)-based vector (26), which was replaced with fusion glycoprotein type E (FuG-E), showing enhanced efficiency of retrograde gene delivery and neuron-specific transduction (25). The transfer plasmid pLV-TRE-EGFP.eTeNT.PEST was based on pFUGW (a gift from D. Baltimore, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA) and constructed by swapping the ubiquitin promoter of the pTRE-Tight vector (Clontech) and EGFP.eTeNT.PEST. The FuG-E vector encoding EGFP.eTeNT was placed downstream of the TRE promoter (FuG-E-TRE-EGFP.eTeNT).

Injections of Viral Vectors.

We injected viral vectors as described by Kinoshita et al. (23). Briefly, the monkeys were anesthetized with isoflurane (1–2%; Abbott Laboratories) throughout the surgery. After a laminectomy of the C4 to C7 vertebrae on the left side, HiRet-TRE-EGFP.eTeNT (titer, 1.54 × 1011 to 1.1 × 1012 copies/mL), FuG-E-TRE-EGFP.eTeNT (titer, 6.6 × 1011 copies/mL), or NeuRet-TRE-EGFP.eTeNT (titer, 7.2 × 1011 copies/mL) was injected via a glass micropipette into the ventral horn (the depth 3.5–4.0 mm from the dorsal surface). A vector solution of 0.5–0.8 μL was injected into each track. To increase the retrograde infection rate of these vectors, monkeys U, S, N, and R received two injections on 2 separate days. A total of 16–23 tracks of injections per day was made at 1-mm intervals in the rostrocaudal direction over the C6 to Th1 spinal segments. AAV-2-CMV-rtTAV16 (titer, 1.4 × 1010 to 1.96 × 1013 particles/mL) or AAV-DJ-CMV-rtTAV16 (titer, 4.8 × 1010 particles/mL) was injected into the intermediate zone (the depth 3.0 mm from the dorsal surface) following the same protocol 1–10 d after the lentiviral injection. A vector solution of 0.5–0.8 μL was injected into each track at 1-mm intervals in the rostrocaudal direction over the caudal C2 to the caudal C4 segments. A total of 12–14 tracks of injections was made. Double-infected neurons, of which cell bodies were located in the C2–C4 and projected to C6–Th1, were expect to generate tetanus neurotoxin, which would block their synaptic transmission during administration of doxycycline (Dox).

Lesion of the CST.

The CST lesion was made following a modified protocol of Sasaki et al. (21) and Nishimura et al. (15). The monkeys were anesthetized with isoflurane (1–2%). After removing adhering soft tissues, the spinal cord was exposed on the left side. A lesion of the dorsolateral funiculus was made 5 mm caudal to the most caudal injection track of the AAV vector, aimed at C4–C5, using a pair of fine forceps. The dorsal part of the lateral funiculus was transected from the dorsal root entry zone ventrally to the level of the lateral ligaments. The lesion was extended ventrally to the most lateral part of the lateral funiculus using forceps. This technique enabled well-controlled and fine lesioning (the rostrocaudal extension; 1.1–1.9 mm). All of the monkeys exhibited limb paralysis immediately after the lesions.

Administration of Dox.

Administration of Dox started 2–3 mo after injections of viral vectors. Dox was dissolved in 3% sucrose in water and administrated orally at a dose of 15 mg⋅kg−1⋅d−1 every morning. Only monkey K received additional intramuscular administration of Dox (10 mg/kg) by injection on the first day.

Behavioral Testing.

During the initial training sessions before the lesion, the monkeys were required to reach for a piece of sweet potato presented through a vertical or 20° inclined slit (8–10 mm width) and to pick it up using the precision grip with the left hand. Each session consisted of 60–100 trials and was performed once or twice a day. After the lesion, some monkeys could reach for the food but not pick it up through the slit using the paretic hand. All of the monkeys were intensively trained to pick up the food through the slit using the paretic hand everyday for 100 trials for 1–3 mo after the lesion. The distance between the food piece and the entrance edge of the slit was kept constant for each monkey except for monkey N, who could not pick up the food at the same distance as before 1 mo after the lesion presumably because of spasticity in digits. Therefore, the food was then presented 6 mm nearer to focus on observing the ability of precision grip. This is why there are no data of success rate for 26 d after the CST lesion in monkey N (Fig. 3C). The hand movements were video filmed from the side (60 frames/s), and the first 30 trials/d were analyzed off-line (30 frames/s). We identified three types of errors (23)—“precision grip error,” “slit-hit-error (hit the edge of the slit),” and “wandering error (repeat gripping)”—and in each session we recorded the total number of trials with one or more of these errors. The success rate for dexterous hand movements in each session was defined as follows:

In monkeys K and R, to compare with our previous results (15, 17, 21, 28), which used the same criterion, only trials with precision grip error were counted. The success rate for dexterous hand movements in each session of these two monkeys was defined as follows:

However, we could still observe clear difference from monkeys with transient blockade of PNs (monkeys U, B, S, and N). We compared the total success rates for 4 d before and after the start of Dox administration in each Dox round of monkeys U, B, S, and N using the Pearson χ2 test (P < 0.05; JMP 10.0.2).

Histological Assessment and Anti-GFP Immunohistochemistry.

At the end of the experiments, the monkeys were deeply anesthetized with i.v. injections of pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg; Somnopentyl; Kyoritsu Seiyaku) and transcardially perfused with 0.05 M PBS and then 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. The brainstem and spinal cord were removed and sectioned at a thickness of 40–60 μm using a cryostat. Every fourth or fifth section were incubated with rabbit anti-GFP antibody (1:2,000; Life Technologies) and then with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:200; Vector Laboratories). The immunoreactive signals were visualized with diaminobenzidine (1:10,000; Wako) containing 1% nickel sodium ammonium and 0.0003% H2O2 in Tris-buffered saline. The sections were counterstained with Neutral Red. GFP-labeled cells were counted in every fourth or fifth section using a BZ-51 microscope (Olympus). Locations of all of the GFP-labeled cells in individual spinal layers from the C2 to C5 segments were reconstructed on a single template selected from the midcervical segments. In monkeys U, B, S, N, and K, one out of every five sections (40-μm thick), and in monkey R, one out of every four sections (60-μm thick) were sampled, respectively. The numbers of cells in pairs of these sections were averaged to estimate the number of PNs within every 400 (monkeys U, B, S, N, and K) or 480 μm (monkey R) of the rostrocaudal extent. The extent of the lesion was calculated as follows: the difference between the entire area of the lateral and ventral funiculus on the unaffected side and the area of the intact part of the lateral and ventral funiculi on the lesioned side was divided by the entire area of the lateral and ventral funiculi on the unaffected side.

Electrophysiological Experiments.

The basic experimental design has been described previously (21–23, 30). Briefly, the monkeys were anesthetized with isoflurane throughout the surgery. Blood pressure was maintained around 100 mmHg and pCO2 at 4.0%. During the recording sessions, anesthesia was changed to α-chloralose (75–100 mg/kg); if the depth of anesthesia was judged to be shallow, sodium pentobarbital (5–10 mg/kg) was occasionally supplemented. The monkeys were paralyzed with repeated administration of pancronium bromide (1.65 mg; Myoblock; Merck Sharp and Dohme) and artificially ventilated. A pneumothorax was created just before recordings. A craniotomy was made to expose the posterior part of the cerebellum and caudal brainstem. The pyramidal electrode was calibrated at the obex (angle 65° from the vertical line) and placed ∼2.5 mm rostrally, 1.5 mm laterally, and at a depth of ∼8.5 mm from the dorsal surface of the brainstem. Monopolar cathodal pulses (0.1-ms duration, 200–300 μA) were applied using tungsten electrodes with an impedance of ∼50–100 kΩ. The threshold for eliciting the descending pyramidal volley was usually ∼5 μA. A laminectomy was made at the C2 to Th1 segments. The deep radial nerve was stimulated with needle electrodes inserted through the skin. Field potential recordings from the deep radial motor nuclei were made using glass capillary electrodes filled with 2 M potassium citrate (impedance, 1–3 MΩ). The locations of the deep radial motor nuclei were determined when the amplitudes of antidromic field potentials were larger than 0.2 mV. Individual recording sites were separated more than 200 μm. The cord dorsum potentials were monitored with a silver ball electrode. Strychnine (0.1 mg/kg, given repeatedly to maintain the excitability level; Sigma-Aldrich) was injected i.v. to reduce glycinergic inhibition from the CST. Dox (10 mg⋅kg−1⋅d−1) was infused i.v. during the experiments to block synaptic transmission through double-infected cells. Completeness of the CST lesion on the affected side was determined by the absence of monosynaptic negative field potentials and direct synaptic volleys. The CST was then lesioned at C4–C5 and subsequently at C2 on the unaffected side and at C2 on the affected side by transecting the dorsolateral funiculus with a pair of fine forceps to dissociate the disynaptic pathway through the PNs. The lesions of C2 on the affected side were not performed when the amplitudes of the disynaptic field potentials on that side were very small. The amplitudes of the disynaptic field potentials were compared with those in the unaffected side using the Wilcoxon test (P < 0.01; JMP 10.0.2).

Discussion

We showed that recovery of dexterous hand movements in monkeys after a CST lesion was perturbed following the blockade of synaptic transmission through the PNs in the midcervical cord segments. The effects of blocking PN transmission depended on when and how long it was blocked along with the ongoing stage recovery. Based on the present findings, we conclude that the PNs exert a stage-dependent contribution to recovery of hand dexterity in monkeys after CST lesions.

Previous studies in rodents suggested that PNs that bypass the lesion might mediate spontaneous recovery after spinal cord injury, which were confirmed by anterograde and retrograde labeling (32, 33) and by lesioning them with NMDA infusions (34). NMDA infusions cause hyperexcitability-induced death of cells that are located in injection sites. Transection of the corticospinal fibers at the rostral level to the PNs impaired recovery (35). These studies suggested a relationship of PNs to recovery, but such lesion might affect other group of neurons besides PNs, and demonstration of causal contribution of PNs was still indirect. Furthermore, because there are considerable differences in neural structures and body apparatus related to hand movements between rodents and primates (12, 36, 37), studies in nonhuman primates are critical for translating therapeutic strategies to treat spinal cord injury in humans (38, 39). Therefore, direct evidence to show the causal contribution of PNs to recovery in nonhuman primates was needed.

In the present transient blockade experiments, the effect of PN blockade on the success rate for dexterous hand movements after CST lesion was similar to that before lesion (Fig. 3C). If the PNs play a major role in recovery, their blockade should be expected to result in much severer impairment than in the intact state; however, the effects were weaker than expected. Two possible explanations might be considered for such low effectiveness of PN blockade on dexterous hand movements after lesion. First, it is possible that other descending pathways, such as the reticulospinal tract (20), the rubrospinal tract (14), and the remaining CST (18) or regenerated CST (5) contributed to the recovery. However, it is unlikely that either the reticulospinal or rubrospinal tracts contributed to recovery of dexterous hand movements in this experiment because synaptic transmission presumably through RSNs to the deep radial MNs was relatively minor (see “after C2 lesion” in Fig. 2I and Fig. S2), and descending axons of the rubrospinal tract were most likely transected in this animal model of spinal cord injury (40). Second, it is possible that the proportion of blocked neurons among the entire PN population was relatively small due to a limited rate of infection by the vectors.

In contrast, the effect of continuous blockade of PNs on recovery was strong and remarkable (Fig. 4). The extent of CST lesions in these two monkeys (K and R in Fig. 1B; 61.5% and 54.5%, respectively; Table S1) was not larger than those in previous studies (15, 17, 21, 28), which would lead us to expect near complete recovery. However, in these two monkeys, alternate grip strategies, which indicate insufficient recovery (41), persisted throughout the entire period of observation. Here, in contrast to the low effectiveness in the transient blockade experiments, recovery of dexterous hand movements was not achieved even 3–4.5 mo after the CST lesion (Fig. 4). Therefore, the context of PN blockade, its timing and length, appear to be critical for the extent of recovery. Blocking PN-mediated pathway at the same time of lesioning the CST made it more difficult to induce recovery than blocking it serially after lesioning the CST. Such phenomenon has also been previously explained by a changed function in unlesioned systems after serial spinal cord lesions in cats (42).

Our previous study showed that the training during the early period after lesion was critical for recovery (29). Early training might be effective in inducing the plasticity of the motor circuits; however, blockade of the PN-mediated pathway at this stage perturbed the effect of training, which might have resulted in poor recovery. Thus, the PN-mediated pathway was likely to have a more significant role in recovery of dexterous hand movements during the early period after lesion. In the present study, we intended to selectively target the descending branch of PNs, which can mediate cortical commands to the lower cervical MNs, using a double-virus infection method. However, it should be kept in mind that, when PN transmission was blocked by the Tet-on system, neural transmission through the ascending PN branches targeting the lateral reticular nucleus, one of the precerebellar nuclei, was also affected due to the bifurcating character of the PNs (23, 30). Therefore, the role of PNs in the recovery of skilled reach and grasp movements revealed in this study may also be dependent on their ascending pathways mediating the efference copy of movements (43), which will be a target of future studies.

As a methodological limitation of this study, we observed blocked neurons in the C5–C6 segments (Fig. 2E and Fig. S2), presumably caused by spread of viral vectors. We could not exclude completely the possibility for partial contribution of sINs in the C5–C6 segments to recovery after CST lesions. However, a few number of MNs in the C5 segment innervate digit muscles, which were thought to play a critical role in dexterous hand movements. Therefore, we did not consider that this affected the main conclusion of this study, namely, the contribution of PNs in the midcervical segments, which may partly include those in the C5 segment that are connected to digit MNs beyond segments, to recovery.

Recently, the reversible, pathway-selective blocking method combined with double-viral vectors was used also to investigate the recovery mechanism for skilled forelimb function in the stroke model rats (44, 45). Wahl et al. (44) showed that, after cortical lesions, administration of an antibody against the antineurite extension protein Nogo-A before intensive rehabilitative training enabled new and functional circuit formation of the CST fibers from the contralesional hemisphere to the contralesional half of the spinal cord, resulting in almost full recovery of skilled forelimb function. On the other hand, Ishida et al. (45) showed that the pathway from the motor cortex to the red nucleus contributed to recovery through intensive training after internal capsule hemorrhage. Thus, this method has great advantages in determining the role of a specific population of neurons in a recovery process after brain and spinal cord injury. Identification of a key neural element involved in the recovery mechanism is crucial, because it can promote development of novel treatments combined with rehabilitation of motor disability following the brain/spinal cord injury. Selectively enhancing the plasticity of the pathways thus identified as being responsible for recovery will become a key technology to facilitate recovery in future studies.

Materials and Methods

The animal experimental procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with the principles of the National Institutes of Health and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan. The protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institutes of Natural Sciences. We recruited eight monkeys and then excluded two because the infection rate and/or expression of viral vectors in one monkey were judged to be obviously insufficient and the extent of lesion of the other monkey was too large; thus, the results of six monkeys are presented. The monkeys were first trained for a few weeks in a reach-and-grasp task described previously (15–17, 21–23) and in Supporting Information (SI Materials and Methods, Behavioral Testing, and Movie S1). The retrograde gene transfer vector (HiRet/FuG-E/NeuRet-TRE-EGFP.eTeNT) was then injected into the ventral horn of the spinal cord at C6–Th1 as previously described (23). One to 10 d after the injection, the anterograde vector (AAV-2/DJ-CMV-rtTAV16) was injected into the intermediate zone of the spinal cord at caudal C2 to caudal C4. Four monkeys (U, B, S, and N) received a total of four rounds of oral Dox (15 mg⋅kg−1⋅d−1, each round, 7–25 d) before and after the CST lesion. Two monkeys (K and R) received continuous administration of Dox from 8–16 d before the CST lesion to 3–4.5 mo after the lesion. Video recordings of reach and grasp movements before and after the lesion were analyzed off-line. The CST lesion was made by transecting the dorsolateral funiculus at C4–C5 under anesthesia with isoflurane (1–2%). After the end of behavioral observations, acute electrophysiological experiments were conducted on the cervical spinal cord in five of the six monkeys (data could not be obtained from monkey R due to a sudden change in the monkey’s condition during the experiment) under anesthesia (see details in SI Materials and Methods). After transcardial perfusion with deep anesthesia, the brains and spinal cords were removed. Histological examinations were conducted with anti-GFP immunohistochemistry. Full materials and methods are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Nishimura, B. Alstermark, and L.-G. Pettersson for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. We thank M. Togawa, Y. Yamanishi, and N. Takahashi for technical support. This study was supported by the Strategic Research Program for Brain Sciences by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) of Japan, and by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (“Adaptive Circuit Shift”) by MEXT (to T.I.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1610787114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Richardson PM, McGuinness UM, Aguayo AJ. Axons from CNS neurons regenerate into PNS grafts. Nature. 1980;284(5753):264–265. doi: 10.1038/284264a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schnell L, Schwab ME. Axonal regeneration in the rat spinal cord produced by an antibody against myelin-associated neurite growth inhibitors. Nature. 1990;343(6255):269–272. doi: 10.1038/343269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnell L, Schneider R, Kolbeck R, Barde YA, Schwab ME. Neurotrophin-3 enhances sprouting of corticospinal tract during development and after adult spinal cord lesion. Nature. 1994;367(6459):170–173. doi: 10.1038/367170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salewski RP, et al. Transplantation of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural stem cells mediate functional recovery following thoracic spinal cord injury through remyelination of axons. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4(7):743–754. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakagawa H, Ninomiya T, Yamashita T, Takada M. Reorganization of corticospinal tract fibers after spinal cord injury in adult macaques. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11986. doi: 10.1038/srep11986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raineteau O, Schwab ME. Plasticity of motor systems after incomplete spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(4):263–273. doi: 10.1038/35067570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishimura Y, Isa T. Compensatory changes at the cerebral cortical level after spinal cord injury. Neuroscientist. 2009;15(5):436–444. doi: 10.1177/1073858408331375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oudega M, Perez MA. Corticospinal reorganization after spinal cord injury. J Physiol. 2012;590(16):3647–3663. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.233189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isa T, Nishimura Y. Plasticity for recovery after partial spinal cord injury—hierarchical organization. Neurosci Res. 2014;78:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernhard CG, Bohm E. Cortical representation and functional significance of the corticomotoneuronal system. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1954;72(4):473–502. doi: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1954.02330040075006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuypers HG. A new look at the organization of the motor system. Prog Brain Res. 1982;57:381–403. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)64138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemon RN. Descending pathways in motor control. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:195–218. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawrence DG, Kuypers HG. The functional organization of the motor system in the monkey. I. The effects of bilateral pyramidal lesions. Brain. 1968;91(1):1–14. doi: 10.1093/brain/91.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawrence DG, Kuypers HG. The functional organization of the motor system in the monkey. II. The effects of lesions of the descending brain-stem pathways. Brain. 1968;91(1):15–36. doi: 10.1093/brain/91.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishimura Y, et al. Time-dependent central compensatory mechanisms of finger dexterity after spinal cord injury. Science. 2007;318(5853):1150–1155. doi: 10.1126/science.1147243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishimura Y, et al. Neural substrates for the motivational regulation of motor recovery after spinal-cord injury. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sawada M, et al. Function of the nucleus accumbens in motor control during recovery after spinal cord injury. Science. 2015;350(6256):98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.aab3825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenzweig ES, et al. Extensive spontaneous plasticity of corticospinal projections after primate spinal cord injury. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(12):1505–1510. doi: 10.1038/nn.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishimura Y, Morichika Y, Isa T. A subcortical oscillatory network contributes to recovery of hand dexterity after spinal cord injury. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 3):709–721. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaaimi B, Edgley SA, Soteropoulos DS, Baker SN. Changes in descending motor pathway connectivity after corticospinal tract lesion in macaque monkey. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 7):2277–2289. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sasaki S, et al. Dexterous finger movements in primate without monosynaptic corticomotoneuronal excitation. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92(5):3142–3147. doi: 10.1152/jn.00342.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alstermark B, et al. Motor command for precision grip in the macaque monkey can be mediated by spinal interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106(1):122–126. doi: 10.1152/jn.00089.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinoshita M, et al. Genetic dissection of the circuit for hand dexterity in primates. Nature. 2012;487(7406):235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature11206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kato S, et al. A lentiviral strategy for highly efficient retrograde gene transfer by pseudotyping with fusion envelope glycoprotein. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22(2):197–206. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kato S, Kobayashi K, Kobayashi K. Improved transduction efficiency of a lentiviral vector for neuron-specific retrograde gene transfer by optimizing the junction of fusion envelope glycoprotein. J Neurosci Methods. 2014;227:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kato S, et al. Neuron-specific gene transfer through retrograde transport of lentiviral vector pseudotyped with a novel type of fusion envelope glycoprotein. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22(12):1511–1523. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto M, et al. Reversible suppression of glutamatergic neurotransmission of cerebellar granule cells in vivo by genetically manipulated expression of tetanus neurotoxin light chain. J Neurosci. 2003;23(17):6759–6767. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06759.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higo N, et al. Increased expression of the growth-associated protein 43 gene in the sensorimotor cortex of the macaque monkey after lesioning the lateral corticospinal tract. J Comp Neurol. 2009;516(6):493–506. doi: 10.1002/cne.22121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sugiyama Y, et al. Effects of early versus late rehabilitative training on manual dexterity after corticospinal tract lesion in macaque monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 2013;109(12):2853–2865. doi: 10.1152/jn.00814.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isa T, Ohki Y, Seki K, Alstermark B. Properties of propriospinal neurons in the C3–C4 segments mediating disynaptic pyramidal excitation to forelimb motoneurons in the macaque monkey. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95(6):3674–3685. doi: 10.1152/jn.00103.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qi HX, Gharbawie OA, Wynne KW, Kaas JH. Impairment and recovery of hand use after unilateral section of the dorsal columns of the spinal cord in squirrel monkeys. Behav Brain Res. 2013;252:363–376. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.05.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bareyre FM, et al. The injured spinal cord spontaneously forms a new intraspinal circuit in adult rats. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(3):269–277. doi: 10.1038/nn1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Filli L, et al. Bridging the gap: A reticulo-propriospinal detour bypassing an incomplete spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2014;34(40):13399–13410. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0701-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Courtine G, et al. Recovery of supraspinal control of stepping via indirect propriospinal relay connections after spinal cord injury. Nat Med. 2008;14(1):69–74. doi: 10.1038/nm1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ueno M, Hayano Y, Nakagawa H, Yamashita T. Intraspinal rewiring of the corticospinal tract requires target-derived brain-derived neurotrophic factor and compensates lost function after brain injury. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 4):1253–1267. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alstermark B, Ogawa J, Isa T. Lack of monosynaptic corticomotoneuronal EPSPs in rats: Disynaptic EPSPs mediated via reticulospinal neurons and polysynaptic EPSPs via segmental interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91(4):1832–1839. doi: 10.1152/jn.00820.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Isa T, Ohki Y, Alstermark B, Pettersson LG, Sasaki S. Direct and indirect cortico-motoneuronal pathways and control of hand/arm movements. Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:145–152. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00045.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Courtine G, et al. Can experiments in nonhuman primates expedite the translation of treatments for spinal cord injury in humans? Nat Med. 2007;13(5):561–566. doi: 10.1038/nm1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedli L, et al. Pronounced species divergence in corticospinal tract reorganization and functional recovery after lateralized spinal cord injury favors primates. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(302):302ra134. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac5811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holstege G, Blok BF, Ralston DD. Anatomical evidence for red nucleus projections to motoneuronal cell groups in the spinal cord of the monkey. Neurosci Lett. 1988;95(1-3):97–101. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90639-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murata Y, et al. Effects of motor training on the recovery of manual dexterity after primary motor cortex lesion in macaque monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99(2):773–786. doi: 10.1152/jn.01001.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alstermark B, Lundberg A, Pettersson LG, Tantisira B, Walkowska M. Motor recovery after serial spinal cord lesions of defined descending pathways in cats. Neurosci Res. 1987;5(1):68–73. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(87)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Azim E, Jiang J, Alstermark B, Jessell TM. Skilled reaching relies on a V2a propriospinal internal copy circuit. Nature. 2014;508(7496):357–363. doi: 10.1038/nature13021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wahl AS, et al. Neuronal repair. Asynchronous therapy restores motor control by rewiring of the rat corticospinal tract after stroke. Science. 2014;344(6189):1250–1255. doi: 10.1126/science.1253050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ishida A, et al. Causal link between the cortico-rubral pathway and functional recovery through forced impaired limb use in rats with stroke. J Neurosci. 2016;36(2):455–467. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2399-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sooksawate T, et al. Viral vector-mediated selective and reversible blockade of the pathway for visual orienting in mice. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:162. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.