Abstract

Background:

Cryptosporidium and Isospora are known as one of the main cause of diarrhea in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised subjects, all over the world. Incidence of enteropathogens such as Cryptosporidium spp. and Isospora belli considerably has increased, since immunodeficiency virus (HIV) rapidly disseminated. In addition, cancer patients are highly susceptible to opportunistic infections. This study aimed to estimate the prevalence of cryptosporidiosis and isosporiasis in immunocompromised patients in Tehran.

Methods:

This study carried out on patients admitted to Imam Khomeini hospital during 2013–2014. Stool samples collected from 350 immunocompromised patients. Formol-ether concentration was performed for all stool samples. Zeil-Neelsen technique was applied to stain the prepared smears and finally, all slides were examined by light microscope.

Results:

Out of 350 patients, 195 (55.7%) and 155 (44.3%) were male and female, respectively. Cryptosporidium oocysts were detected in 3 (0.9%) samples including one sample from HIV+/AIDS patients and 2 samples from organ transplant recipients. Isospora oocysts were detected in 4 (1.1%) samples consisting 2 HIV+/AIDS patients, one patients suffering from malignancy and one patients with other immunodeficiency diseases.

Conclusion:

Cryptosporidium sp, and I. belli are the most prevalent gastrointestinal parasitic protozoans that infect a broad range of individuals, particularly those patients who have a suppressed or deficient immunity system.

Keywords: Cryptosporidiosis, Isosporiasis, Immunocompromised, Iran

Introduction

Coccidian genuses are microscopic protozoan parasites that infect the intestinal tract of the majority of human and animal subjects. These organisms are one of the major concerns for physicians, especially with increasing the rate of immunodeficiency disorders. The coccidian parasites (Cryptosporidium spp., Isospora belli, and Cyclospora spp.) are the most common enteric parasites in immunocompromised patients that can usually lead to lethal severe diarrhea while are considered as causative agents of a mild and self-limiting gastrointestinal disorders in immunocompetent individuals (1).

Cryptosporidium and Isospora are recognized as significant and widespread causes of diarrheic disease in both immunocompetent and immunosuppressed individuals that has also been described as traveler disease (2, 3). Incidence of gastrointestinal parasites, especially Cryptosporidium sp. and I. belli considerably has increased, since immunodeficiency disorders rapidly disseminated. These two parasites display many similarities in their clinical symptoms (4). Diarrhea is one of the major complications, approximately occurring in 90% of HIV/AIDS patients and with low prevalence in other acquired and/or congenital immunodeficiency conditions, particularly in developing countries (5). Cancer patients and transplantation recipients who take immunosuppressive therapy and also patients with metabolic disorders are highly susceptible to opportunistic infections (6).

Acute or chronic diarrheic syndromes resulting from these parasites are usually accompanied by weight loss, dehydration, abdominal pain, and mal-absorption syndrome in immunocompromised patients (4). Chronic diarrhea can lead to the increase in morbidity and mortality in these patients (4). Diarrhea with fluid loss of 25 L/day has been seen in infected patients, which can persist for weeks in immunocompromised patients (6).

Cryptosporidium infects the microvillus border of the gastrointestinal epithelium of many vertebrate hosts (7). There are 5 known species of Cryptosporidium (C. hominis, C. parvum, C. meleagridis, C. felis, and C. canis), capable to induce human cryptosporidiosis that C. parvum and C. hominis are considered as more common species (8).

I. belli is one of the opportunistic coccidian parasites that affects HIV+/AIDS patients, especially in developing countries of Africa, Asia, and Latin America with low levels of hygiene. It is always considered as a neglected parasite and the presence of this parasite because of the lack of enough investigation, particularly in immunocompromised patients, is underestimated (9).

Various risk factors like using contaminated drinking water, animal exposure etc., have been reported to be associated with the gastrointestinal infection (10). There are several studies in Iran mainly on Cryptosporidium spp (11–14). Most of the published studies on Isospora in Iran are focused on case reports (15–18). The prevalence rate of Cryptosporidium spp., infection has been studied in different groups of people such as immunocompromised patients as well as diarrheic children. It was even reported up to 11.5% in chronic hemodialysis patients (13).

The aim of this study was to provide new insight into the prevalence of cryptosporidiosis and isosporiasis in immunocompromised patients in Iran.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was carried out at the laboratory of Intestinal Parasitic Protozoans, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Tehran. Stool samples were collected from patients suffering from acquired/congenital immunodeficiency and/or those patients who had undergone immunosuppressive medications, during 2013–2014. All patients had been admitted to Imam Khomeini Hospital in one of the three following sections including Infectious, Oncology and Transplantation Departments. All stool samples of the patients were immediately transferred to the laboratory of Intestinal Parasitic Protozoans in Department of Medical Parasitology and Mycology, Tehran University of Medical Science for further investigations.

Totally, 350 stool samples were collected from four groups of immunocompromised patients consisting 80 (23%) HIV/AIDS individuals with CD4+ lymphocyte count of less than 200 cells/μL and a history of Anti-Retroviral Therapy (ART), 15 (4%) organ transplant recipients, 234 (67%) patients suffering from malignancy undergoing chemotherapy and 21 (6%) patients with other congenital/acquired immunodeficiency disorders.

Conventional formalin-ether concentration was performed for all stool samples. Slim slides were prepared for each sample and then all slides were dried in room temperature and were fixed with absolute methanol for 1 min. Finally, all samples were stained using conventional Zeil-Neelsen method. Microscopic examination was performed for each slide with at least 200–300 fields using 100× oil immersion objective. All slides were examined by an observer and positive slides confirmed by second observer.

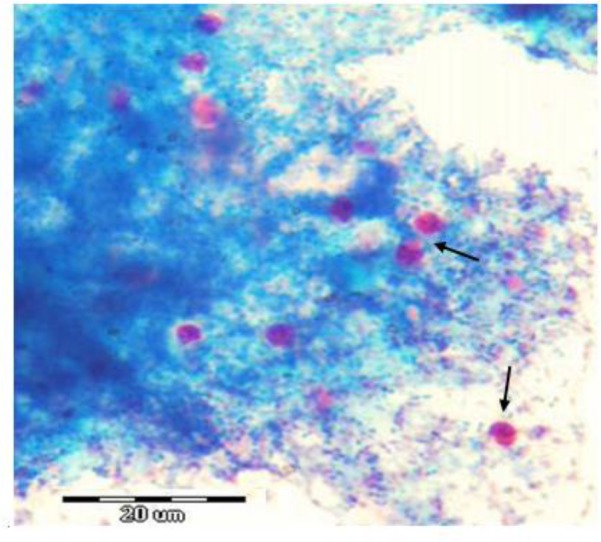

Stool specimens containing un-sporulated oocysts were kept in potassium dichromate 2% at room temperature to develop two mature sporocysts after 4–5 d (Fig. 1, 2c).

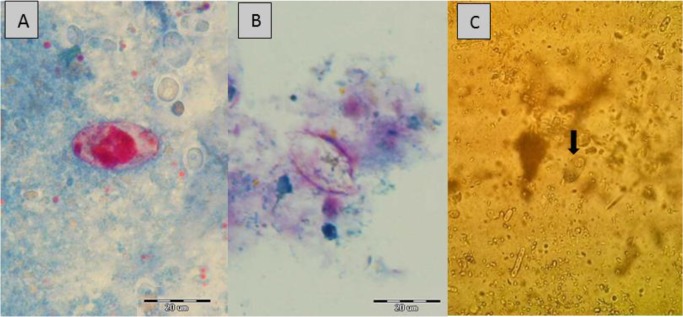

Fig. 1:

Oocysts of Cryptosporidium isolated from stool in Zeil-NeelsenStain

Fig. 2:

Oocysts of Isospora isolated from stool in Ziehl-Nielsen Stain; variation in staining of sporoblast ; Red-stained oocyst (A); Unstained ghost (B); Sporulated oocyst in direct wet smear (C)

Results

Out of 350 patients, 195(55.7%) were male and 155(44.3%) were female. The mean+ SD of age of patients was 45.5 + 15.41 yr. Cryptosporidium sp, and I. belli were the only coccidian detected. Coccidian oocysts were identified in 7 (2%) of the stool samples. Cryptosporidium oocysts were detected in 3 (0.9%) samples including one HIV/AIDS patients and 2 organ transplant recipients (Table 1). Isospora oocysts were detected in 4 (1.1%) samples consist of 2 HIV/AIDS patients, one patients suffering from malignancy and one patients with other congenital/acquired immunodeficiency disorders.

Table 1:

Prevalence of coccidian parasites identified in different groups of patients

| Number of patients | Cryptosporidium Number (%) | Isospora Number (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIDS patients | 80 | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.5) |

| Organtransplant recipients | 15 | 2 (13.3) | 0 |

| Malignancy | 234 | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Other congenital/acquired immunodeficiency disorders | 21 | 0 (0) | 1 (4.7) |

| Total | 350 | 3 (0.9) | 4 (1.1) |

Discussion

Cryptosporidium, Isospora and Cyclospora are increasingly becoming prevalent in immunocompromised patients. Humans can acquire cryptosporidial infections through the fecal-oral route via direct person-to-person or animal-to-person contact as well as consumption of contaminated water or food (19) while no animal reservoir was identified for human isosporiasis (20).

Although, animals are known as potential source of cryptosporidiosis, but environmental water resources are also described as one of the main sources of Cryptosporidium (21). Cryptosporidium spp., could be found in surface and groundwater resources via fecal contamination, that can infect drinking water resources (22). Interestingly, Cryptosporidium oocysts are able to pass through water treatment process because of their small size and resistance to routine disinfectants (8). Cryptosporidium transmission also occurs in care centers of children that share toilets and common play areas, or through diaper changing (6). However, the rate of infection is different from 0.6 – 85% for Cryptosporidium and 0.2–20% for I. belli depending on the study population and detection techniques (4).

Cryptosporidium oocysts were recorded from 6.1 and 2.1% of general population of developing and developed countries, respectively (21). However, the prevalence rates of cryptosporidiosis among HIV+/AIDS diarrheic patients were significantly higher than 10% (21). Another study that reported a prevalence rate of cryptosporidiosis in 7% of diarrheic children represented a significant positive correlation between the infection and under-weight children. (11). Results of the study on diarrheic AIDS or AML patients in health centers of Tehran showed that the prevalence of cryptosporidiosis was 33.4% and 11.1%, respectively (12). Prevalence of cryptosporidiosis in hemodialysis patients was higher than control groups in Iran (13).

HIV status was associated with infection of Cryptosporidium, I. belli, and Strongyloides stercoralis. However, HIV likely had no significant effects on increasing reports of the prevalence of other protozoan or helminthic infections (23).

The common human-coccidian parasites were significantly seen in HIV/AIDS patients compared with healthy control subjects (1, 14, 23, 24). In the current study, a high prevalence of Cryptosporidium and Isospora in HIV/AIDS patients together with reduced CD4 lymphocyte count confirms susceptibility of HIV/AIDS patients to opportunistic infections.

Although, isosporiasis has worldwide distribution especially in tropical and subtropical regions, but there are rare reports of this infection (25). I. belli is considered as an opportunistic infection in immunocompromised individuals, mainly AIDS patients, all over the world. Isosporiasis has been reported as the most prevalent intestinal parasitic disease among AIDS patients (26, 27). Assis and colleagues reported the frequency rate 10.1% and 6.7% in HIV-positive patients for Cryptosporidium sp., and I. belli, respectively (28). In another study, the prevalence rate of isosporiasis in Nigeria was reported 3.1% in HIV-positive patients while no Isospora infection was observed in the healthy control (25). Our results showed that the frequency rate of isosporiasis in HIV/AIDS patients was 2.5%. Therefore, our finding is in agreement with other studies that have suggested low prevalence rate of isosporiasis in immunocompromised patients, particularly HIV/AIDS patients. However, although treatment of isosporiasis usually is successful but recurrence cases are common (26). Detection of Isospora in direct examination of stool samples in most of laboratories is unusual. On the other hand, cases of isosporiasis has being raised up together with increase of HIV-infected subjects that can increase gastrointestinal complications in immunocompromised patients.

Few studies have conducted on isosporiasis in Iran (14, 29). The first human isosporiasis was reported in 1961 and the second one was recorded from a 9-yr-old girl in Mashhad (16). Afterwards, 10 cases of human infection with I. belli were presented in 1991 in Iran (17). Another study reported isosporiasis from a patient who had been hospitalized due to car accident in 2001 (15). The first report of co-infection of Cryptosporidium and Isospora in Iran was carried out from an AIDS patient suffering from diarrhea in 2006 (7). A study showed Isospora infection from a 3-yr-old girl with HIV infection (18). Isosporiasis is usually transmitted through ingestion of sporulated oocysts from contaminated food and water (20). Although, some of cases of isosporiasis have been reported from homosexual patients (30), but because of the fact that isospora oocysts require to mature and become infectious in the environment, direct fecal-oral contact is unlikely to be the rout of usual transmission (31). Therefore, sanitation of water and food is very important in prevention programs. However, as mentioned, although isosporiasis reports are low, but this infection should be considered as a neglected disease in Iran, particularly in those subjects that have immunity disorders.

Conclusion

Cryptosporidium spp., and I. belli are the most prevalent gastrointestinal parasitic protozoans that infect a broad range of patients who have a suppressed or deficient immune system.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the Lab. Staffs of the Intestinal Protozoa Laboratory, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Dr. Khadijeh Khanaliha, Mrs. Fatemeh Tarighi, Mrs. Zeinab Askari and Mrs. Tahereh Rezaian for their sincere cooperation. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Gupta S, Narang S, Nunavath V, Singh S. Chronic diarrhoea in HIV patients: prevalence of coccidian parasites. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2008; 26( 2): 172– 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ryan ET, Wilson ME, Kain KC. Illness after international travel. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347( 7): 505– 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ud Din N, Torka P, Hutchison RE, Riddell SW, Wright J, Gajra A. Severe Isospora (Cystoisospora) belli diarrhea preceding the diagnosis of human T-cell-leukemia-virus-1-associated T-cell lymphoma. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2012; 2012: 640104 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Oliveira-Silva MB1, de Oliveira LR, Resende JC, Peghini BC, Ramirez LE, Lages-Silva E, Correia D. Seasonal profile and level of CD4+ lymphocytes in the occurrence of cryptosporidiosis and cystoisosporidiosis in HIV/AIDS patients in the Triângulo Mineiro region, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2007; 40( 5): 512– 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vignesh R, Balakrishnan P, Shankar EM, Murugavel KG, Hanas S, Cecelia AJ, et al. High proportion of isosporiasis among HIV-infected patients with diarrhea in southern India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007; 77( 5): 823– 4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baqai R, Anwar S, Kazmi SU. Detection of Cryptosporidium in immunosuppressed patients. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2005; 17( 3): 38– 40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nahrevanian H, Assmar M. A case report of Cryptosporidiosis and Isosporiasis in AIDS patients in Iran. J Trop Med Parasitol. 2006; 29( 1): 33– 6. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cho EJ, Yang JY, Lee ES, Kim SC, Cha SY, Kim ST, et al. A Waterborne Outbreak and Detection of Cryptosporidium Oocysts in Drinking Water of an Older High-Rise Apartment Complex in Seoul. Korean J Parasitol. 2013; 51( 4): 461– 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Certad G, Arenas-Pinto A, Pocaterra L, Ferrara G, Castro J, Bello A, et al. Isosporiasis in Venezuelan adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus: clinical characterization. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003; 69( 2): 217– 22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dwivedi KK, Prasad G, Saini S, Mahajan S, Lal S, Baveja UK. Enteric opportunistic parasites among HIV infected individuals: associated risk factors and immune status. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2007; 60( 2–3): 76– 81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hamedi Y, Safa O, Haidari M. Cryptosporidium infection in diarrheic children in southeastern Iran. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005; 24( 1): 86– 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nahrevanian H, Assmar M. Cryptosporidiosis in immunocompromised patients in the Islamic Republic of Iran. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2008; 41( 1): 74– 7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seyrafian S, Pestehchian N, Kerdegari M, Yousefi HA, Bastani B. Prevalence rate of Cryptosporidium infection in hemodialysis patients in Iran. Hemodial Int. 2006; 10( 4): 375– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meamar AR, Rezaian M, Mohraz M, Zahabian F, Hadighi R, Kia E. A comparative analysis of intestinal parasitic infections between HIV+/AIDS patients and non-HIV infected individuals. Iran J Parasitol. 2007; 2( 1): 1– 6. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hazrati TK, Mohamadzadeh A, Mohamadi A, Yousefi M. ( 2001 . ). A case report of Isospora belli from west Azerbayjan province.Iran. Urmia Med J. 2001: 288– 295. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ghorbani MRM. Human infection with Isospora hominis. A case report. Iran J Public Health, 1985 . ; 14 ( 1–4 ): 9 –15. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rezaeian M. A report of 10 cases of human Isosporiasis in Iran. Medical Journal of The Islamic Republic of Iran (MJIRI). 1991; 5( 1): 45– 7. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nateghi Rostami M, Nikmanesh B, Haghi-Ashtiani MT, Monajemzadeh M, Douraghi M, Ghalavand Z, et al. Isospora belli associated recurrent diarrhea in a child with AIDS. J Parasit Dis. 2014; 38( 4): 444– 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang L, Xiao L, Duan L, Ye J, Guo Y, Guo M, et al. Concurrent infections of Giardia duodenalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, and Clostridium difficile in children during a cryptosporidiosis outbreak in a pediatric hospital in China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013; 7( 9): e2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Castañeda Hernandez DM. Protozoa: Cystoisospora belli (Syn. Isospora belli). In: Encyclopedia of Food Safety; Editors: Motarjemi Y, Moy GG, Todd ECD,. Academic Press ; ; 2014 . ; 45 –8. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee JK, Song HJ, Yu JR. Prevalence of diarrhea caused by Cryptosporidium parvum in non-HIV patients in Jeollanam-do, Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2005; 43( 3): 111– 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Peletz R, Mahin T, Elliott M, Montgomery M, Clasen T. Preventing cryptosporidiosis: the need for safe drinking water. Bull World Health Organ. 2013; 91( 4): 238– 8A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Assefa S, Erko B, Medhin G, Assefa Z, Shimelis T. Intestinal parasitic infections in relation to HIV/AIDS status, diarrhea and CD4 T-cell count. BMC Infect Dis. 2009; 9( 1): 155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kelly P, Todd J, Sianongo S, Mwansa J, Sinsungwe H, Katubulushi M, et al. Susceptibility to intestinal infection and diarrhoea in Zambian adults in relation to HIV status and CD4 count. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009; 9( 1): 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Olusegun AF, Okaka CE, Luiz Dantas Machado R. Isosporiasis in HIV/AIDS Patients in Edo state, Nigeria. Malays J Med Sci. 2009; 16( 3): 41– 44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lindsay DS, Dubey J, Blagburn BL. Biology of Isospora spp. from humans, nonhuman primates, and domestic animals. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997; 10( 1): 19– 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kumar SS, Ananthan S, Lakshmi P. Intestinal parasitic infection in HIV infected patients with diarrhoea in Chennai. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2002; 20( 2): 88– 91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Assis DC, Resende DV, Cabrine-Santos M, Correia D, Oliveira-Silva MB. Prevalence and genetic characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. and Cystoisospora belli in HIV-infected patients. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2013; 55( 3): S0036-46652013000300149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ghorban NDA, Nahravanian H, Asmar M, Amirkhani A, Esfandiari B. Frequency of cryptosporidiosis and isoporiasis and other enteropathogenic parasites in gastroenteritic patients (Babol and Babolsar; 2005–2006). JBUMS. 2008; 10( 2): 56– 61. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Forthal DN, Guest SS. Isospora belli enteritis in three homosexual men. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1984; 33( 6): 1060– 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lumb R, Hardiman R. Isospora belli infection. A report of two cases in patients with AIDS. Med J Australia. 1991; 155( 3): 194– 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]