Abstract

Background

Letters of complaint written by patients and their advocates reporting poor healthcare experiences represent an under-used data source. The lack of a method for extracting reliable data from these heterogeneous letters hinders their use for monitoring and learning. To address this gap, we report on the development and reliability testing of the Healthcare Complaints Analysis Tool (HCAT).

Methods

HCAT was developed from a taxonomy of healthcare complaints reported in a previously published systematic review. It introduces the novel idea that complaints should be analysed in terms of severity. Recruiting three groups of educated lay participants (n=58, n=58, n=55), we refined the taxonomy through three iterations of discriminant content validity testing. We then supplemented this refined taxonomy with explicit coding procedures for seven problem categories (each with four levels of severity), stage of care and harm. These combined elements were further refined through iterative coding of a UK national sample of healthcare complaints (n= 25, n=80, n=137, n=839). To assess reliability and accuracy for the resultant tool, 14 educated lay participants coded a referent sample of 125 healthcare complaints.

Results

The seven HCAT problem categories (quality, safety, environment, institutional processes, listening, communication, and respect and patient rights) were found to be conceptually distinct. On average, raters identified 1.94 problems (SD=0.26) per complaint letter. Coders exhibited substantial reliability in identifying problems at four levels of severity; moderate and substantial reliability in identifying stages of care (except for ‘discharge/transfer’ that was only fairly reliable) and substantial reliability in identifying overall harm.

Conclusions

HCAT is not only the first reliable tool for coding complaints, it is the first tool to measure the severity of complaints. It facilitates service monitoring and organisational learning and it enables future research examining whether healthcare complaints are a leading indicator of poor service outcomes. HCAT is freely available to download and use.

Keywords: Quality measurement, Patient safety, Communication, Ordinary knowledge, Patient-centred care

Introduction

Improving the analysis of complaints by patients and families about poor healthcare experiences (herein termed ‘healthcare complaints’) is an urgent priority for service providers1–3 and researchers.4 5 It is increasingly recognised that patients can provide reliable data on a range of issues,6–12 and healthcare complaints have been shown to reveal problems in patient care (eg, medical errors, breaching clinical standards, poor communication) not captured through safety and quality monitoring systems (ie, incident reporting, case review and risk management).13–15 Patients are valuable sources of data for multiple reasons. First, patients and families, collectively, observe a huge amount of data points within healthcare settings;16 second, they have privileged access to information on continuity of care,17 18 communication failures,19 dignity issues20 and patient-centred care;21 third, once treatment is concluded, they are more free than staff to speak up;22 fourth, they are outside the organisation, thus providing an independent assessment that reflects the norms and expectations of society.23 Moreover, patients and their families filter the data, only writing complaints when a threshold of dissatisfaction has been crossed.24

Unlocking the potential of healthcare complaints requires more than encouraging and facilitating complaint reporting (eg, patients being unclear about how to complain, believing complaints to be ineffective or fearing negative consequences for their healthcare),3 25 it also requires systematic procedures for analysing the complaints, as is the case with adverse event data.4 It has even been suggested that patient complaints might actually precede, rather than follow, safety incidents, potentially acting as an early warning system.5 26 However, any systematic investigation of such potential requires a reliable and valid tool for coding and analysing healthcare complaints. Existing tools lag far behind established methods for analysing adverse events and critical incidents.27–31 The present article answers recent calls to develop reliable method for analysing healthcare complaints.4 5 31 32

A previous systematic review of 59 articles reporting healthcare complaint coding tools revealed critical limitations with the way healthcare complaints are analysed.26 First, there is no established taxonomy for categorising healthcare complaints. Existing taxonomies differ widely (eg, 40% do not code safety-related data), mix general issues with specific issues, fail to distinguish problems from stages of care and lack a theoretical basis. Second, there is minimal standardisation of the procedures (eg, coding guidelines, training), and no Healthcare Complaints Analysis Tool (HCAT) has been thoroughly tested for reliability (ie, that two coders will observe the same problems within a complaint). Third, analysis of healthcare complaints often overlooks secondary issues in favour of single issues. Finally, despite the varying severity of problems raised (eg, from parking charges to gross medical negligence), existing tools do not assess complaint severity.

To begin addressing these limitations, the previous systematic review26 aggregated the coding taxonomies from the 59 studies, revealing 729 uniquely worded codes, which were refined and conceptualised into seven categories and three broad domains (http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/23/8/678/F4.large.jpg). The overarching tripartite distinction between clinical, management and relational domains represents theory and practice on healthcare delivery. The ‘clinical domain’ refers to the behaviour of clinical staff and relates to the literature on human factors and safety.33–35 The ‘management domain’ refers to the behaviour of administrative, technical and facilities staff and relates to the literature on health service management.36–38 The ‘relationship domain’ refers to patients’ encounters with staff and relates to the literatures on patient perspectives,39 misunderstandings,40 empathy41 and dignity.20 These domains also have an empirical basis in studies of patient–doctor interaction, where the discourses (or ‘voices’) of medicine, institutions and patients are evident,41 42 and clashes between the ‘system’ (clinical and management domains) and ‘lifeworld’ (relational domain) are observed.43–45 Although the taxonomy developed in the systematic review26 is comprehensive and theoretically informed, it remains a first step. It needs to be extended into a tool, similar to those used in adverse event research,20–22 that can reliably distinguish the types of problem reported, their severity and the stages of care at which they occur.

Our aim is to create a tool that supports healthcare organisations to listen46 to complaints, and to analyse and aggregate these data in order to improve service monitoring and organisational learning. Although healthcare complaints are heterogeneous47 and require detailed redress at an individual level,48 we demonstrate that complaints and associated severity levels can be reliably identified and aggregated. Although this process necessarily loses the voice of individual complainants, it can enable the collective voice of complainants to inform service monitoring and learning in healthcare institutions.

Method

Tool development often entails separate phases of development, refinement and testing.49 50 We developed and tested the HCAT through three phases (for which ethical approval was sought and obtained) with the following aims:

To test and refine the conceptual validity of the original taxonomy.

To develop the refined taxonomy into a comprehensive rating tool, with robust guidelines capable of distinguishing problems, their severity and stages of care.

To test the reliability and calibration of the tool.

Phase 1: testing and refining discriminant content validity

Discriminant content validity examines whether a measure (eg, questionnaire item) or code (eg, for categorising data) accurately reflects the construct in terms of content, and whether a number of measures or codes are clearly distinct in terms of content (ie, that they do not overlap).51 To assess whether the categories identified in the original systematic review26 conceptually subsumed the subcategories and whether these categories were distinct from each other, we followed a six-step discriminant content validity procedure.51 First, we listed definitions of the problem categories and their associated domains. Second, we listed the subcategories as the items to be sorted into the categories. Third, we recruited three groups (n=58, n=58, n=55) of non-expert, but educated lay participants from a university participant pool (comprising students from a range of degree programmes across London who were paid £5 for 30 min) to perform the sorting exercise. Fourth, participants sorted each of the subcategories into one of the seven problem categories and provided a confidence rating on a scale of 0–10. In addition, we asked participants to indicate whether the subcategory item being sorted was either a ‘problem’ or a ‘stage of care’. Fifth, we analysed the data to examine the extent to which each subcategory item was sorted under their expected category and participants’ confidence. Finally, we used this procedure to revise the taxonomy through three rounds of testing.

Phase 2: tool development through iterative application

To broaden the refined taxonomy into a comprehensive tool, we first incorporated coding procedures established in the literature. To record background details, we used the codes most commonly reported in the healthcare complaint literature,26 namely: (1) who made the complaint (family member, patient or unspecified/other), (2) gender of the patient (female, male or unspecified/other) and (3) which staff the complaint refers to (administrative, medical, nursing or unspecified/other). To record the stage of care, we adopted the five basic stages of care coded within adverse event reports,52 namely: (1) admissions, (2) examination and diagnosis, (3) care on the ward, (4) operation and procedures and (5) discharge and transfers. To record harm, we used the UK National Reporting and Learning System's risk matrix,53 which has a five-point scale ranging from minimal harm (1) to catastrophic harm (5).

Next, we aimed to (1) identify the range of severity for each category and identify ‘indicators’ that covered the diversity of complaints within each category, both in terms of content and severity; (2) evaluate the procedures for coding background details, stage of care and harm and (3) establish clear guidelines for the coding process as explicit criteria have been linked to inter-rater reliability.54 We used an iterative qualitative approach (repeatedly applying HCAT to healthcare complaints) because it is suited for creating taxonomies (in our case indicators) that ensure a diversity of issues can be covered parsimoniously.55 Also, through experiencing the complexity of coding healthcare complaints, this iterative qualitative approach allowed for us to refine both the codes and the coding guidelines.

We used the Freedom of Information Act to obtain a redacted (ie, all personally identifying information removed) random sample (of 7%) of the complaints received from 52 healthcare conglomerates (termed ‘Trust’) during the period April 2011 to March 2012. This yielded a dataset of 1082 letters, about 1% of the 107 000 complaints received by NHS Trusts during the period. This sample reflects the population of UK healthcare complaints with a CI of 3 and a confidence level of 95%.

The authors then separately coded subsamples of the complaint letters using HCAT, subsequently meeting to discuss discrepancies. Once sufficient insight had been gained, HCAT was revised and another iteration of coding ensued. After four iterations (n= 25, n=80, n=137, n=839), the sample of complaints was exhausted, and we had reached saturation56 (ie, the fourth iteration resulted in minimal revisions).

Phase 3: testing tool reliability and calibration

To test the reliability and calibration of HCAT, we created a ‘referent standard’ of 125 healthcare complaints.57 This was a stratified subsample of the 1081 healthcare complaints described in the previous section. To construct the referent standard, the authors separately coded the letters and then agreed on the most appropriate ratings. Letters were included such that the referent standard comprised at least five occurrences of each problem at each severity level (ie, so it was possible to test the reliability of coding for all HCAT problems and severity levels). Because healthcare complaints often relate to multiple problem categories (and some are less common than others), it was impossible to have a completely balanced distribution (table 1). These letters were all type written (either letters or emails), digitally scanned, with length varying from 645 characters to 14 365 characters (mean 2680.58, SD 1897.03).

Table 1.

Distribution of Healthcare Complaints Analysis Tool problem severity across the referent standard

| Not present (rated 0) | Low (rated 1) | Medium (rated 2) | High (rated 3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality | 81 | 10 | 22 | 12 |

| Safety | 73 | 5 | 24 | 23 |

| Environment | 101 | 6 | 10 | 8 |

| Institutional processes | 86 | 10 | 18 | 11 |

| Listening | 99 | 5 | 11 | 10 |

| Communication | 96 | 7 | 14 | 8 |

| Respect and patient rights | 88 | 19 | 13 | 5 |

To test the reliability of HCAT, 14 participants with MSc-level psychology education were recruited from the host department as ‘raters’ to apply HCAT to the referent standard. We chose educated non-expert raters because complaints are routinely coded by educated non-clinical experts, for example, hospital administrators.26 There are no fixed criteria on the number of raters required to assess the reliability of a coding framework,58 59 and a relatively large group of raters (n=14) was recruited in order to provide a robust test of reliability and better understand any variations in coding. Raters were trained during one of two 5 h training courses (each with seven raters). Training included an introduction to HCAT, applying HCAT to 10 healthcare complaints (three in a group setting and seven individually) and receiving feedback. Raters then had 20 h to work independently to code the 125 healthcare complaints. SPSS Statistics V.21 and AgreeStat V.3.2 were used to test reliability and calibration.

First, we used Gwet's AC1 statistic to test among raters the inter-rater reliability of coding for complaint categories and their underlying severity ratings (not present (0), low (1), medium (2) and high (3)).60 61 This test examines the reliability of scoring for two or more coders using a categorical rating scale, taking into account skewed datasets, where there are several categories and the distributions of one rating occurs at a much higher rate than another62 (ie, 0 s in the current study because the majority of categories are not present in each letter). Furthermore, quadratic ratings were applied, in order that large discrepancies in ratings (ie, between 0 and 3) were treated as more significant in terms of indicating poor reliability than small discrepancies (ie, between 2 and 3).60 Gwet's AC1 test was also applied to test for inter-rater reliability in coding the stages of care complained about. Although Gwet's AC1 is the most appropriate test for the data, we also calculated Fleiss’ κ because this is more commonly used and provides a more conservative test (because it ignores the skewed distribution). Finally, because harm was rated as a continuous variable, an intraclass correlation (ICC) coefficient was used to test for reliability. To interpret the coefficients, the following commonly used guidelines60 63 were followed: 0.01–0.20=poor/slight agreement; 0.21–0.40=fair agreement; 0.41–0.60=moderate agreement; 0.61–0.80=substantial agreement and 0.81–1.00=excellent agreement.

Second, we tested whether the 14 raters applied HCAT to the problem categories in a manner consistent with the referent standard (ie, as coded by the authors). Gwet's AC1 (weighted) was calculated by comparing each rater's coding of problem categories and severity against the referent standard and then calculating an average Gwet's AC1 score. The average inter-rater reliability coefficient (ie, across all 14 raters) was then calculated for each problem category in order to provide an overall assessment of calibration. Again, Fleiss’ κ was also calculated in order to provide a more conservative test.

Results

Phase 1: discriminant content validity results

The first test of discriminant content validity revealed large differences in the correct sorting of subcategories by participants (range 21%–97%, mean=76.19%, SD=19.35%). There was overlap between ‘institutional issues’ (bureaucracy, environment, finance and billing, service issues, staffing and resources) and ‘timing and access’ (access and admission, delays, discharge and referrals). The ‘humaneness/caring’ category was also problematic, with subcategory items often miscategorised as ‘patient rights’ or ‘communication.’ Finally, participants would often classify subcategory items as a ‘stage of care’.

Accordingly, we revised the problematic categories and subcategories twice. During these revisions, we removed reference to stages of care (ie, subcategory items ‘admissions’, ‘examinations’ and ‘discharge’), we merged ‘humaneness/caring’ into ‘respect and patient rights’ and in light of recent literature that emphasises the importance of listening,64 65 we created a new category ‘listening’ (information moving from patients to staff) as distinct from ‘communication’ (information moving from staff to patients). Also, we reconceptualised the management domain as ‘environment’ and ‘institutional processes’, which proved easier for participants to distinguish. The third and final test of discriminant content validity yielded much improved results, with subcategory items being correctly sorted into the categories and domains on average 85.65% of the time (range, 58%–100%; SD, 10.89%).

Phase 2: creating the HCAT

Applying HCAT to actual letters of healthcare complaint revealed that reliable coding at the subcategory level was difficult. However, while the raters often disagreed at the subcategory level, they agreed at the category level. Accordingly, the decision was made to focus on the reliability of the three domains and seven categories, with the subcategories shaping the severity indicators for each category. This decision to focus on the macro structure of HCAT is consistent with the overall aim of HCAT to identify macro trends rather than to identify and resolve individual complaints.

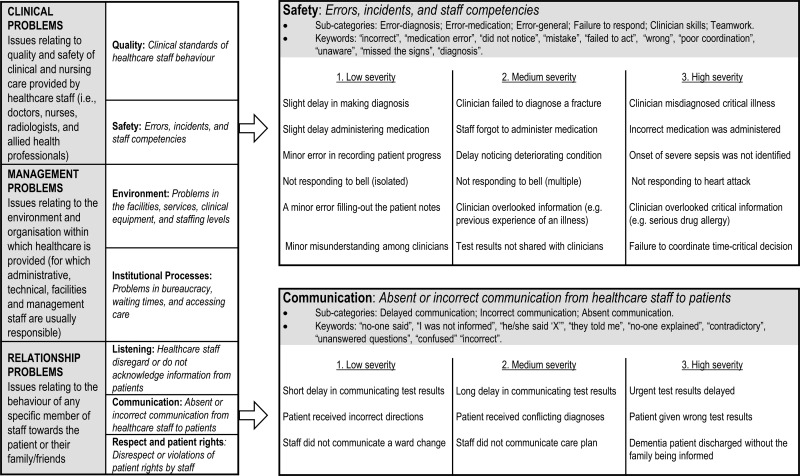

To develop severity indicators for each category, we iteratively applied the refined taxonomy to four samples (n=25, n=80, n=137, n=839) of healthcare complaints. These sample sizes were determined by the necessity to change some aspects of the tool. The increasing sample sizes reveal that fewer changes were required as the iterative refinement of the tool progressed. Rather than applying an abstract scale of severity, we identified vivid indicators of severity, appropriate to each problem category and subcategory, which should be used to guide coding. Figure 1 reports the final HCAT problem categories and illustrative severity indicators.

Figure 1.

The Healthcare Complaints Analysis Tool domains and problem categories with severity indicators for the safety and communication categories.

The coding procedures for background details, stage of care and harm proved relatively unproblematic to apply. The only modifications necessary included adding an ‘unspecified or other’ category for stage of care and a harm category ‘0’ for when no information on harm was available.

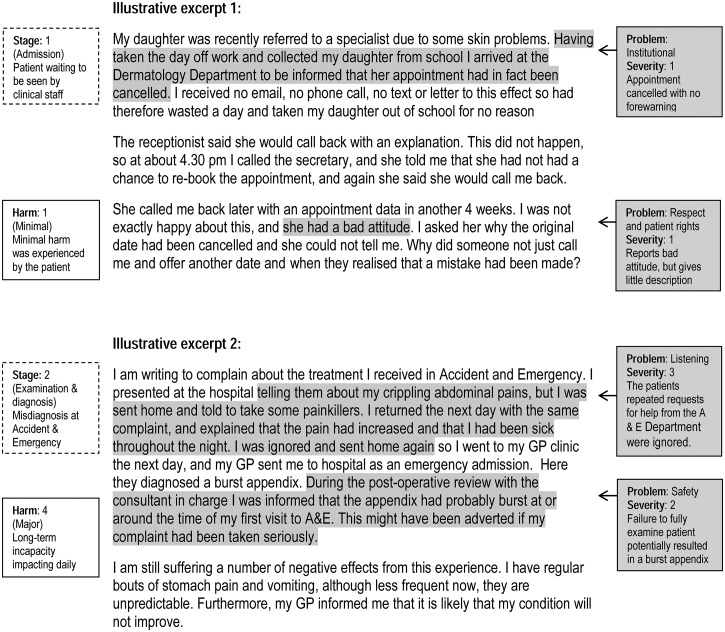

Resolving disagreements about how to apply HCAT to a specific healthcare complaint led us to the development of a set of guidelines for coding healthcare complaints (box 1). The final version of the HCAT, with all the severity indicators and guidelines, is freely available to download (see online supplementary file). Figure 2 demonstrates applying HCAT to illustrative excerpts.

Box 1. The guidelines for coding healthcare complaints with Healthcare Complaints Analysis Tool.

Coding should be based on empirically identifiable text, not on inferences.

No judgement should be made of the intentions of the complainant, their right to complain or the importance they attach to the problems they describe.

Each hospital complaint is assessed for the presence of each problem category, and where a category is not identified, it is coded as not present.

Severity ratings are independent of outcomes (ie, harm) and not comparable across problem categories.

Coding severity should be based on the provided indicators, which reflect the severity distribution within the problem category.

When one problem category is present at multiple levels of severity, the highest level of severity is recorded.

Each problem should be associated with at least one stage of care (a problem can relate to multiple stages of care).

Harm relates exclusively to the harm resulting from the incident being complained about.

Figure 2.

Applying Healthcare Complaints Analysis Tool to letters of complaint (excerpts are illustrative, not actual). GP, general practitioner.

Phase 3: reliability and calibration of results

The results of the reliability analysis are reported in table 2. On average, raters applied 1.94 codes per letter (SD, 0.26). The Gwet's AC1 coefficients reveal that the problem categories, each with four levels of severity, were reliably coded (ie, with substantial agreement or better). Safety showed least reliability (0.69), and respect and patient rights showed most reliability (0.91). Additional analysis using Fleiss’ κ (which takes no account of the skewed data) found moderate to substantial reliability for all problem categories and severity ratings (0.48 (listening)–0.61 (safety, respect and patient rights)). The most significant discrepancies between Gwet's AC1 and Fleiss’ κ occur on the items with the largest skew (ie, listening), thus underscoring the problem with Fleiss’ κ and our rationale for privileging Gwet's AC1. For stages of care, one showed substantial agreement (care on the ward), three showed moderate agreement (admissions, examination and diagnosis, operation or procedure) and one had only fair agreement (discharge/transfer). Demographic data were coded at substantial reliability or higher. The ICC coefficient also demonstrated harm to be coded reliably (ICC, 0.68; 95% CI 0.62 to 0.75).

Table 2.

Reliability of raters (n=14) coding 125 healthcare complaints

| Gwet's AC1 | 95% CI | Fleiss’ κ | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCAT problem categories | ||||

| Quality | 0.72 | 0.65 to 0.80 | 0.50 | 0.41 to 0.58 |

| Safety | 0.69 | 0.61 to 0.76 | 0.61 | 0.54 to 0.69 |

| Environment | 0.85 | 0.88 to 0.94 | 0.60 | 0.51 to 0.70 |

| Institutional processes | 0.81 | 0.75 to 0.86 | 0.58 | 0.49 to 0.66 |

| Listening | 0.86 | 0.82 to 0.91 | 0.48 | 0.52 to 0.70 |

| Communication | 0.81 | 0.76 to 0.86 | 0.52 | 0.44 to 0.61 |

| Respect and patient rights | 0.91 | 0.88 to 0.95 | 0.61 | 0.52 to 0.70 |

| Stages of care | ||||

| Admissions | 0.45 | 0.47 to 0.67 | 0.45 | 0.35 to 0.55 |

| Examination and diagnosis | 0.57 | 0.49 to 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.50 to 0.65 |

| Operation or procedure | 0.58 | 0.47 to 0.68 | 0.57 | 0.47 to 0.67 |

| Care on the ward | 0.66 | 0.47 to 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.47 to 0.67 |

| Discharge/transfer | 0.38 | 0.25 to 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.35 to 0.55 |

| Complainer | ||||

| Patient | 0.90 | 0.86 to 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.86 to 0.94 |

| Family member | 0.89 | 0.84 to 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.81 to 0.92 |

| Patient gender | ||||

| Male | 0.92 | 0.88 to 0.96 | 0.85 | 0.79 to 0.92 |

| Female | 0.89 | 0.85 to 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.84 to 0.93 |

| Complained about | ||||

| Medical staff | 0.63 | 0.60 to 0.70 | 0.63 | 0.56 to 0.69 |

| Nursing staff | 0.64 | 0.57 to 0.70 | 0.64 | 0.56 to 0.70 |

| Administrative staff | 0.62 | 0.54 to 0.70 | 0.62 | 0.54 to 0.70 |

p<0.001 for all tests.

HCAT, Healthcare Complaints Analysis Tool.

The results of the calibration analysis are reported in table 3. Gwet's AC1 scores show raters, on average, to have substantial and excellent reliability against the referent standard. Fleiss’ κ scores show substantial agreement (0.62–0.67). Further analysis revealed some raters to be better calibrated (across all categories) against the referent standard than others.

Table 3.

Average calibration of raters (n=14) against the referent standard

| Average Gwet's AC1 | Range | Fleiss’ κ | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCAT problem categories | ||||

| Quality | 0.79 | 0.59 to 0.88 | 0.62 | 0.45 to 0.77 |

| Safety | 0.76 | 0.69 to 0.83 | 0.68 | 0.49 to 0.78 |

| Environment | 0.89 | 0.73 to 0.94 | 0.67 | 0.49 to 0.78 |

| Institutional processes | 0.84 | 0.73 to 0.89 | 0.63 | 0.58 to 0.072 |

| Listening | 0.89 | 0.82 to 0.94 | 0.62 | 0.52 to 0.077 |

| Communication | 0.86 | 0.72 to 0.93 | 0.62 | 0.41 to 0.76 |

| Respect and patient rights | 0.91 | 0.87 to 0.94 | 0.65 | 0.51 to 0.72 |

p<0.001 for all tests.

HCAT, Healthcare Complaints Analysis Tool.

Finally, exploratory analysis indicated that the length of letter (in terms of characters per letter) was negatively associated with reliability in coding for listening (r=0.266, p<0.01), communication (r=0.211, p<0.05) and environment (r=0.202, p<0.05). It was not associated with reliability in coding for respect and patient rights, institutional processes, safety or quality. Furthermore, there was no relationship between the number of codes applied per letter and the length of the letter.

Discussion

The present article has reported on the development and testing of a tool for analysing healthcare complaints. The aim is to facilitate organisational listening,46 to respond to the ethical imperative to listen to grievances66 and to improve the effectiveness of healthcare delivery by incorporating the voice of patients.4 Many complainants aim to contribute information that will improve healthcare delivery,67 yet to date there has been no reliable tool for aggregating this voice of patients in order to support system-level monitoring and learning.4 5 25 The present article establishes HCAT as capable of reliably identifying the problems, severity, stage of care, and harm reported in healthcare complaints. This tool contributes to the three domains that it monitors.

First, HCAT contributes to monitoring and enhancing clinical safety and quality. It is well documented that existing tools (eg, case reviews, incident reporting) are limited in the type and range of incidents they capture,13 68 and that healthcare complaints are an underused data source for augmenting existing monitoring tools.1 2 4

The lack of a reliable tool for distinguishing problem types and severity has been an obstacle.5 26 HCAT provides a reliable additional data stream for monitoring healthcare safety and quality.69

Second, HCAT can contribute to understanding the relational side of patient experience. Nearly, one third of healthcare complaints relate to the relationship domain,26 and a better understanding of these problems, and how they relate to clinical and management practice, is essential for improving patient satisfaction and perceptions of health services.4 67 These softer aspects of care have proved difficult to monitor,70–72 and again, HCAT can provide a reliable additional data stream.

Third, HCAT can contribute to the management of healthcare. Concretely, HCAT could be integrated into existing complaint coding processes such that the HCAT severity ratings can then be extracted and passed onto managers, external monitors and researchers. HCAT could be used as an alternative metric of success in meeting standards (eg, on hospital hygiene, waiting times, patient satisfaction). It could also be used longitudinally as a means to assess clinical, management or relationship interventions. Additionally, HCAT could be used to benchmark units or regions. Accumulating normative data would allow for healthcare organisations to be compared for deviations (eg, poor or excellent complaint profiles), and this would facilitate interorganisational learning (eg, sharing practice).73

Across these three domains, HCAT can bring into decision-making the distinctive voice of patients, providing an external perspective (eg, in comparison with staff and incidents reports) on the culture of healthcare organisations. For example, where safety culture is poor (and thus incident reporting likely to be low), the analysis of complaints can provide a benchmark that is independent of that poor culture.

Finally, one of the main innovations of HCAT is the ability to reliably code severity within each complaint category. To date, analysis of healthcare complaints has been limited to frequency of problem occurrence (regardless of severity). This effectively penalises institutions that actively solicit complaints to improve quality; it might be that the optimum complaint profile is a high percentage of low-severity complaints, as this would demonstrate that the institution facilitates complaints and has managed to protect against severe failures.

Future research

Having a reliable tool for analysing healthcare complaints paves the way for empirically examining recent suggestions that healthcare complaints might be a leading indicator of outcome variables.4 5 There is already evidence that complaints predict individual outcomes;74 the next question is whether a pattern of complaints can predict organisation-level outcomes. For example: Do severe clinical complaints correlate with hospital-level mortality or safety incidents? Might complaints about management correlate with waiting times? Do relationship complaints correlate with patient satisfaction? If any such relationships are found, then the question will become whether healthcare complaints are leading or lagging indicators.

Limitations

One limitation of the current research is that the inter-rater reliability, despite being moderate to substantial, has room for improvement. For example, the reliability of applying the listening, communication and environment categories was moderately associated with length of letter, indicating the need to improve how these categories are applied to longer and potentially more complex letters. This highlights the challenge of attempting to analyse and learn from complex and diverse written experiences. Healthcare complaints report interpretations of patient experiences and HCAT, in turn, interprets and codifies these experiences. This complexity results in inevitable variability in how complaints are understood and coded, especially for the relationship problems, such as listening and communication (which showed the weakest reliability using Fleiss’ Kappa). In order to improve reliability, future research might have healthcare professionals code the letters (eg, for comparing clinical vs non-clinical rater groups). Also, given that HCAT has only been tested on complaints from the UK, further research is needed to assess its application in other national contexts.

A second limitation is that HCAT was not tested for reliability at the subcategory level; instead, we focused on the seven overarching problem categories. To make HCAT a tool that can be applied universally, we have had to reduce the specificity of the problems that it aims to reliably identify. The rationale is that it is more useful to measure severity reliably for these seven categories than have unreliable and unscaled measurements of fine-grained problems. Nonetheless, the problem categories are underpinned by more specific subcategory codes (on which the indicators are based) that could be used by healthcare institutions while retaining the basic structure of HCAT (three domains and seven categories). This would ensure that data would be comparable across institutions.

A final limitation is that the data used in the present analysis, despite coming from a range of healthcare institutions, do not include general practice (GP) complaints (because these are not handled by the NHS Trusts in the UK). Accordingly, using HCAT for GP care, a specialist unit or a specific cultural context might require some adaptation. In such cases, we recommend preserving the HCAT structure of three domains and seven categories, which we hope will prove to be broadly applicable, and instead adding appropriate severity indicators within the relevant categories.

Conclusion

Historically, healthcare complaints have been viewed as particular to a patient or member of staff.4 Increasingly, however, there have been calls to better use the information communicated to healthcare services through complaints.1 4 5 HCAT addresses these calls to identify and record the value and insight in patient reported experiences. Specifically, HCAT provides a reliable and theoretically robust framework through which healthcare complaints can be monitored, learnt from and examined in relation to healthcare outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Jane Roberts, Kevin Corti and Mark Noort for their help with data collection and analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: AG and TR contributed equally to the conceptualisation, design, acquisition, analysis, interpretation and write up of the data. Both authors contributed equally to all aspects of developing the Healthcare Complaints Analysis Tool and writing the article. Both authors approve the submitted version of the article.

Funding: London School of Economics and Political Science.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: London School of Economics and Political Science Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data from the discriminant content validity study and the reliability study are available. Please contact the authors for details.

References

- 1.Francis R. Independent Inquiry into care provided by Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust January 2005–March 2009. Norwich, UK: The Stationery Office, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donaldson L. An organisation with a memory: report of an expert group on learning from adverse events in the NHS. Norwich, UK: The Statutory Office, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clwyd A, Hart T. A review of the NHS Hospitals complaints system: Putting patients back in the picture. London, UK: Department of Health, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallagher TH, Mazor KM. Taking complaints seriously: using the patient safety lens. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:352–5. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroening H, Kerr B, Bruce J, et al. . Patient complaints as predictors of patient safety incidents. Patient Exp J 2015;2:94–101. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basch E. The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med 2010;362:865–9. 10.1056/NEJMp0911494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koutantji M, Davis R, Vincent C, et al. . The patient's role in patient safety: engaging patients, their representatives, and health professionals. Clin Risk 2005;11:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pittet D, Panesar SS, Wilson K, et al. . Involving the patient to ask about hospital hand hygiene: a National Patient Safety Agency feasibility study. J Hosp Infect 2011;77:299–303. 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward JK, Armitage G. Can patients report patient safety incidents in a hospital setting? A systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:685–99. 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawton R, O'Hara JK, Sheard L, et al. . Can staff and patient perspectives on hospital safety predict harm-free care? An analysis of staff and patient survey data and routinely collected outcomes. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:369–76. 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor BB, Marcantonio ER, Pagovich O, et al. . Do medical inpatients who report poor service quality experience more adverse events and medical errors? Med Care 2008;46:224–8. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181589ba4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Entwistle VA. Differing perspectives on patient involvement in patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:82–3. 10.1136/qshc.2006.020362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levtzion-Korach O, Frankel A, Alcalai H, et al. . Integrating incident data from five reporting systems to assess patient safety: making sense of the elephant. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2010;36:402–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weingart SN, Pagovich O, Sands DZ, et al. . What can hospitalized patients tell us about adverse events? Learning from patient-reported incidents. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:830–6. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0180.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weingart SN, Pagovich O, Sands DZ, et al. . Patient-reported service quality on a medicine unit. Int J Qual Health Care 2006;18:95–101. 10.1093/intqhc/mzi087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pukk-Harenstam K, Ask J, Brommels M, et al. . Analysis of 23 364 patient-generated, physician-reviewed malpractice claims from a non-tort, blame-free, national patient insurance system: Lessons learned from Sweden. Postgrad Med J 2009;85:69–73. 10.1136/qshc.2007.022897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, et al. . Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ 2003;327:1219–21. 10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care-a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1064–71. 10.1056/NEJMhpr0706165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers AE, Addington-Hall JM, Abery AJ, et al. . Knowledge and communication difficulties for patients with chronic heart failure: qualitative study. BMJ 2000;321:605–7. 10.1136/bmj.321.7261.605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobson N. Dignity and health: a review. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:292–302. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart M. Towards a global definition of patient centred care. BMJ 2001;322:444–5. 10.1136/bmj.322.7284.444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okuyama A, Wagner C, Bijnen B. Speaking up for patient safety by hospital-based health care professionals: a literature review. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:61 10.1186/1472-6963-14-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toop L. Primary care: core values patient centred primary care. BMJ 1998;316:1882–3. 10.1136/bmj.316.7148.1882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulcahy L, Tritter JQ. Pathways, pyramids and icebergs? Mapping the links between dissatisfaction and complaints. Sociol Health Illn 1998;20:825–47. 10.1111/1467-9566.00131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Entwistle VA, McCaughan D, Watt IS, et al. . Speaking up about safety concerns: multi-setting qualitative study of patients’ views and experiences. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:e33 10.1136/qshc.2009.039743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reader TW, Gillespie A, Roberts J. Patient complaints in healthcare systems: a systematic review and coding taxonomy. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:678–89. 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murff HJ, France DJ, Blackford J, et al. . Relationship between patient complaints and surgical complications. Qual Saf Health Care 2006;15:13–16. 10.1136/qshc.2005.013847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherman H, Castro G, Fletcher M, et al. . Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: The conceptual framework. Int J Qual Health Care 2009;21:2–8. 10.1093/intqhc/mzn054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Runciman W, Hibbert P, Thomson R, et al. . Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: key concepts and terms. Int J Qual Health Care 2009;21:18–26. 10.1093/intqhc/mzn057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Runciman WB, Baker GR, Michel P, et al. . Tracing the foundations of a conceptual framework for a patient safety ontology. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:e56 10.1136/qshc.2009.035147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vincent C, Taylor-Adams S, Stanhope N. Framework for analysing risk and safety in clinical medicine. BMJ 1998;316:1154–7. 10.1136/bmj.316.7138.1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beaupert F, Carney T, Chiarella M, et al. . Regulating healthcare complaints: a literature review. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 2014;27:505–18. 10.1108/IJHCQA-05-2013-0053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vincent C. Patient safety. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Vries EN, Ramrattan MA, Smorenburg SM, et al. . The incidence and nature of in-hospital adverse events: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:216–23. 10.1136/qshc.2007.023622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wachter RM, Pronovost PJ. Balancing “no blame” with accountability in patient safety. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1401–6. 10.1056/NEJMsb0903885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kenagy JW, Berwick DM, Shore MF. Service quality in health care. JAMA 1999;281:661–5. 10.1001/jama.281.7.661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swayne LE, Duncan WJ, Ginter PM. Strategic management of health care organizations. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferlie EB, Shortell SM. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: a framework for change. Milbank Q 2001;79:281–315. 10.1111/1468-0009.00206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Attree M. Patients’ and relatives’ experiences and perspectives of “good” and “not so good” quality care. J Adv Nurs 2001;33:456–66. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01689.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gillespie A, Moore H. Translating and transforming care: people with brain injury and caregivers filling in a disability claim form. Qual Health Res 2015. 10.1177/1049732315575316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, et al. . Physician empathy: Definition, components, measurement, and relationship to gender and specialty. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159: 1563–9. 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mishler EG. The discourse of medicine: dialectics of medical interviews. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Pub, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clark JA, Mishler EG. Attending to patients’ stories: reframing the clinical task. Sociol Health Illn 1992;14:344–72. 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11357498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenhalgh T, Robb N, Scambler G. Communicative and strategic action in interpreted consultations in primary health care: a Habermasian perspective. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:1170–87. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Habermas J. The theory of communicative action: lifeworld and system: a critique of functionalist reason. Cambridge, UK: Polity, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Macnamara J. Creating an “architecture of listening” in organizations. Sydney, NSW: University of Technology Sydney, 2015. http://www.uts.edu.au/sites/default/files/fass-organizational-listening.pdf (accessed 9 Jul 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lloyd-Bostock S, Mulcahy L. The social psychology of making and responding to hospital complaints: an account model of complaint processes. Law Policy 1994;16:123–47. 10.1111/j.1467-9930.1994.tb00120.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Donaldson LJ, Cavanagh J. Clinical complaints and their handling: a time for change? Qual Saf Health Care 1992;1:21–5. 10.1136/qshc.1.1.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Michie S, Ashford S, Sniehotta FF, et al. . A refined taxonomy of behaviour change techniques to help people change their physical activity and healthy eating behaviours: the CALO-RE taxonomy. Psychol Health 2011;26:1479–98. 10.1080/08870446.2010.540664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yule S, Flin R, Paterson-Brown S, et al. . Development of a rating system for surgeons’ non-technical skills. Med Educ 2006;40:1098–104. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02610.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnston M, Dixon D, Hart J, et al. . Discriminant content validity: a quantitative methodology for assessing content of theory-based measures, with illustrative applications. Br J Health Psychol 2014;19:240–57. 10.1111/bjhp.12095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woloshynowych M, Neale G, Vincent C. Case record review of adverse events: a new approach. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12:411–15. 10.1136/qhc.12.6.411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.A risk matrix for risk managers. National Patient Safety Agency 2008. http://www.nrls.nhs.uk/resources/?entryid45=59833&p=13 (accessed 14 May 2015).

- 54.Lilford R, Edwards A, Girling A, et al. . Inter-rater reliability of case-note audit: a systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy 2007;12:173–80. 10.1258/135581907781543012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res 2007;42:1758–72. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sandelowski M. Sample size in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health 1995;18:179–83. 10.1002/nur.4770180211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Timmermans S, Berg M. The gold standard: the challenge of evidence-based medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 58.LeBreton JM, Senter JL. Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organ Res Methods 2007;11:815–52. 10.1177/1094428106296642 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lamb BW, Wong HWL, Vincent C, et al. . Teamwork and team performance in multidisciplinary cancer teams: development and evaluation of an observational assessment tool. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:849–56. 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.048660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gwet KL. Handbook of inter-rater reliability: the definitive guide to measuring the extent of agreement among raters. Gaithersburg, MD: Advanced Analytics, LLC, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hallgren KA. Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: an overview and tutorial. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol 2012;8:23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wongpakaran N, Wongpakaran T, Wedding D, et al. . A comparison of Cohen's Kappa and Gwet's AC1 when calculating inter-rater reliability coefficients: a study conducted with personality disorder samples. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:61 10.1186/1471-2288-13-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Southwick FS, Cranley NM, Hallisy JA. A patient-initiated voluntary online survey of adverse medical events: the perspective of 696 injured patients and families. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:620–9.. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-003980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jones A, Kelly D. Deafening silence? Time to reconsider whether organisations are silent or deaf when things go wrong. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:709–13. 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Couldry N. Why voice matters: culture and politics after neoliberalism. London, UK: Sage Publications, 2010. doi:10.1111/hex.12373 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bouwman R, Bomhoff M, Robben P, et al. . Patients’ perspectives on the role of their complaints in the regulatory process. Health Expect 2015. 10.1111/hex.12373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Christiaans-Dingelhoff I, Smits M, Zwaan L, et al. . To what extent are adverse events found in patient records reported by patients and healthcare professionals via complaints, claims and incident reports? BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:49 10.1186/1472-6963-11-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reason J. Human error: models and management. BMJ 2000;320:768–70. 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gill L, White L. A critical review of patient satisfaction. Leadersh Health Serv 2009;22:8–19. 10.1108/17511870910927994 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Boudreaux ED, O'Hea EL. Patient satisfaction in the Emergency Department: a review of the literature and implications for practice. J Emerg Med 2004;26: 13–26. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2003.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Greaves F, Laverty AA, Millett C. Friends and family test results only moderately associated with conventional measures of hospital quality. BMJ 2013;347:f4986 10.1136/bmj.f4986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mearns K, Whitaker SM, Flin R. Benchmarking safety climate in hazardous environments: a longitudinal, interorganizational approach. Risk Anal 2001;21:771–86. 10.1111/0272-4332.214149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Järvelin J, Häkkinen U. Can patient injury claims be utilised as a quality indicator? Health Policy 2012;104:155–62. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.